The day of Princess Kate’s birth marked the beginning of five years of happiness for Kate and her mother and father. But then Princess Kate’s daddy died. For the next three years, Kate, missing her daddy, followed the men of the kingdom. From the horsemen she learned how to ride. From the woodsmen she learned how to walk in the forest and never get lost, and which berries and plants were safe to eat and which were not. She grew so sturdy and so strong she could crack nuts open with her bare hands. So, everyone began calling her Kate Crackernuts.

In a nearby kingdom, there lived a princess named Annie whose life was almost exactly like Kate’s. For five years she and her mother and father lived happily. But then Princess Annie’s mama died. For the next three years, Annie, missing her mama, watched the women of the palace. She watched them sew. She watched them embroider, and she watched them dance. She hoped she could learn to create such beauty, even without a mama to teach her.

When Princess Kate and Princess Annie were eight years old, Kate’s mother and Annie’s father fell in love and married. Kate Crackernuts and Annie became stepsisters—sisters joined by marriage who quickly grew to love each other more than most sisters joined by blood.

Time passed. When Kate’s mother decided it was time to teach Kate the womanly arts of sewing, embroidery, and dancing, she thought she might as well teach Annie too. Annie loved the lessons. Between lessons she practiced her growing skills. Kate suffered through the lessons. When each lesson ended, she hurried outside to walk in the woods.

“Kate,” her mother scolded, “you must develop your skills. You are a princess. Without skills you’ll never find a husband. No prince wants to marry a princess who cannot sew, embroider, and dance.”

“Oh, Mama, I won’t marry a prince who cares about sewing, embroidery, and dancing. I’ll marry a prince who wants to walk in the woods, never get lost, and never feel hungry.”

Kate’s mother thought, “No such prince exists.”

More time passed. Kate and Annie grew old enough to attend dances. Whenever the two sisters arrived at a ball, all the young men flocked around Annie.

“Promise me a dance, Annie.”

“Save a dance for me, Annie.”

“Annie, may I have a dance with you?”

Not until Annie had the name of a prince written beside every dance on her dance card did the young men turn their attention to Kate. Kate didn’t care. She enjoyed watching the young men hover around Annie because she knew Annie loved dancing.

Kate’s mother watched, and Kate’s mother worried: “How will my Kate ever find a husband with Annie so beautiful and so graceful. Kate simply does not have a chance. Annie is much too beautiful. . . . Perhaps I could destroy Annie’s beauty?”

One day Kate’s mother went to see the henwife, a woman known for creating spells, and she arranged a spell to destroy Annie’s beauty. The next morning Kate’s mother said, “Annie, go see the henwife for me. She promised me something.”

“I’ll go right after breakfast.”

“No, Annie, go now. It’s very important.” As Annie walked through the palace, she stopped at the pantry and grabbed a crust of bread to eat on her way. When she reached the henwife’s home, the henwife said, “Good morning, Annie. Come in. See what’s in this pot.”

Annie lifted the lid of the pot. Nothing happened.

“Annie,” asked the henwife, “have you eaten this morning?” When the henwife learned about the crust of bread, she said, “Take this advice to your stepmother—keep your pantry better locked.” Annie took the advice home.

The next morning, Kate’s mother walked Annie all the way to the door of the palace. “Hurry to the henwife’s for me, Annie.”

As Annie walked to the henwife’s she saw gardeners picking peas. She stopped and talked with them. They offered her fresh peas to eat, and she ate them. When she lifted the pot lid at the henwife’s house, again nothing happened. When the henwife learned about the peas, she said, “Take this advice to your stepmother: The pot won’t boil when the fire’s away.”

Annie took the advice home. “She said to tell you the pot won’t boil when the fire’s away.” When Kate’s mother heard this, she knew she needed to go with Annie.

The next morning, Kate’s mother said, “Annie, dear, come to the henwife’s with me.” This time, when Annie lifted the lid of the pot a sheep’s head rose into the air, flew over to Annie, and pushed itself down over her beautiful head, covering it completely. Annie tried to pull the sheep’s head off, but it was stuck fast to her shoulders. She tried to call for help, but all she could say was, “Baaaa, baaaa.”

“Oh, Annie, let’s go home!” said her stepmother.

When they neared their palace, Kate’s mother called, “Kate, Kate, come see what happened to Annie.”

Kate ran from the palace. When she saw her sister, she cried, “Annie, oh Annie, what happened?”

Annie’s frightened eyes peered from the eye sockets of the sheep, but all she could say was, “Baaaa, baaaa.”

“Oh, Kate,” her mother gushed, “Isn’t it wonderful! Now all the young men will pay attention to you. You’ll have your pick of princes. I can’t imagine there’s a prince in the entire world who will want to marry a young woman with a sheep’s head.”

“Mama, you caused this?”

“I did it for you, Kate, I did it for you. Isn’t it wonderful!”

“Oh, Mama, no. No!” Kate ran into the palace. Soon she returned carrying traveling cloaks and a fine linen cloth. Gently, she wrapped the cloth around Annie’s head. Kate made sure Annie could see and breathe easily, yet no one would be able to see the sheep’s head. Then Kate took Annie by the hand, turned away from her home, and walked toward the woods.

“Kate?” her mother called, “What are you doing? Where do you think you’re going? I’m your mother, Kate. Come back here.”

Tears streamed down Kate’s cheeks, but she held fast to Annie’s hand.

“Kate? Come back here! You needed my help, Kate. You’ll see. You needed my help!”

Kate kept crying, and Kate kept walking.

For days Kate and Annie traveled through the forest, but they were never hungry. At night, they slept side by side, bundled in their traveling cloaks. One day they walked out of the forest and into another kingdom.

In this kingdom, the king and queen had two sons. One prince was said to be handsome and healthy. The other lay sick and dying and no one knew the cause or the cure. The king had proclaimed, “Anyone who spends the night with my sick son will receive a pound of silver.” Many tried to spend the night with the prince, but all who tried were never heard from again.

“A pound of silver?” thought Kate. “Annie and I will need money. I must try.” So, Kate and Annie went to see the king.

“I’ll spend the night with your sick son in exchange for the pound of silver and a safe place for my sick sister to rest.” The king agreed. He took Annie to a fine room, and then he led Kate to his son’s room.

The prince slept in his bed. Kate watched and waited. Night came. Nothing happened. But when midnight arrived, the prince opened his eyes, climbed out of bed, and walked past Kate as if he could not even see her. Kate followed him from the palace and out to the stable. The prince saddled his horse. When he mounted his horse, Kate Crackernuts jumped up behind him and they rode away into the forest. As they rode by trees, Kate grabbed nuts and dropped them in her apron. They rode and they rode. At last the prince stopped in front of a green hill and called, “Open, green hill. Admit the prince and his horse.”

And in a voice Kate hoped sounded like the prince, she added, “And his lady.”

The green hill opened. Kate and the prince rode into another world. In this world, they rode on a broad path edged by tall trees. The path ended at a magnificent house. When the prince stopped his horse, Kate Crackernuts slid off and hid in nearby bushes. The door of the house opened, and fairies ran out, calling, “Oh, it’s the prince—our dancing partner!”

The fairies dragged the prince from his horse and pulled him into the house. Kate slipped into the house behind them, taking care to hide in the shadows. Kate watched as the fairies danced with the prince. They danced and danced and danced with him. They would not let him eat. They would not let him drink. They made him dance and dance.

Only when a cock crowed the coming morning did the fairies let him go. The prince stumbled outside and struggled onto his horse. Kate slipped out and jumped up behind him. Back they rode to the palace, where the prince fell into his bed.

When the king arrived to check on his son, he found the prince asleep in bed and Kate Crackernuts sitting in front of the fire cracking nuts open with her bare hands. “I’ve learned what ails the prince,” she said, “but I don’t know how to cure him. I will spend another night with him for a pound of gold.” The king agreed.

That night, Kate didn’t watch the prince dance. Instead, she crept in the shadows, listening to the fairies, and this is what she heard:

“Any news from the palace?” one asked.

“Sheep’s head Annie is visiting,” another laughed.

“Oh, what a wonderful spell that one is!” said a third, “Ugly, ugly, ugly.”

“Oh yes, effective, but simple,” said another. “Why, three stokes of any wand, even the one the baby’s playing with—would break that spell.”

Kate thought, “Where’s the baby? That wand is mine.” Kate crept in the shadows until she found a fairy baby playing with a wand. She took nuts from her apron and, one by one, she rolled the nuts past the baby. The fairy baby acted just like any human baby. The baby watched nut after nut roll by. Then the baby laughed, dropped the wand, and crawled off after the nuts.

Kate snatched the wand, hid it in her apron, and then slipped out to await the prince.

When she returned to the palace, Kate hurried to Annie’s room. Three times she stroked the sheep’s head with the wand. The sheep’s head vanished—Annie’s beauty restored!

“Now, Annie,” said Kate, “I understand there is a handsome, healthy prince living in this palace. Why don’t you see if you can meet him? I’m off to make another bargain with the king.”

When the king came to his son’s room, Kate was waiting for him. “I still don’t know how to cure him, but I’ll spend another night with him, if I may marry him.” The king agreed.

That night Kate again crept in the shadows and listened to the fairies talk:

“Just think, three more nights of dancing and the prince will be ours.”

“Oh, that’s right,” another fairy gloated. “He’ll never return to the palace and no one will know what happened to him. He’ll be our dancing partner forever and ever.”

“It is a complicated, time-consuming spell, but it’s nearly complete.”

“Oh yes! The only way to interrupt it now would be to feed the prince a stew made from the little yellow birdie the baby’s playing with . . .”

Kate thought, “Where’s that baby?” She crept in the shadows until she found the baby playing with the birdie. Again she rolled nut after nut. Finally the baby laughed, let go of the birdie, and crawled after the nuts. Kate snatched the yellow birdie, hid it in her apron, and slipped out to await the prince.

When they returned to the palace, the prince fell into his bed. Kate wrung the yellow birdie’s neck, plucked off all its feathers, dropped it into a pot of water, and began cooking yellow birdie stew. The aroma from the cooking pot drifted over to the sleeping prince. He opened his eyes, “Oh, what is that wonderful smell?”

“Yellow birdie stew,” said Kate. She filled a bowl and carried it to his bed. Gently Kate lifted the prince’s head and spooned yellow birdie stew into his mouth.

“More,” said the prince, and he propped himself up on his elbows. Kate fed him more.

“More, please,” said the prince, and he sat up in his bed. Kate fed him more.

“More, please,” he said, and he stood up. Kate Crackernuts handed him the entire bowl.

When the king came to check on his son, he found Kate Crackernuts sitting in front of the fire, cracking nuts open with her bare hands. Beside her sat the prince, helping himself to yellow birdie stew, laughing, talking, and falling in love with Kate Crackernuts.

Annie and the other prince fell in love too.

In time, a grand double wedding was held. After the wedding ceremony, celebrations lasted for days and days. Annie and her prince attended every celebration and danced every dance. Kate and her prince attended every celebration and danced the first dance at each one—just to be polite. Then they slipped away for walks in the woods.

Kate’s prince never did like dancing. He had no idea why he did not like dancing, he just thought, “I don’t enjoy dancing.” But he loved walking in the woods, never getting lost, and never feeling hungry, because he walked beside his beloved Kate Crackernuts.

I first encountered this tale in the version retold by Joseph Jacobs in English Fairy Tales, where he included this source note: “Given by Mr. Lang in Longmans’ Magazine, vol. xiv. (not xiii as cited in Folk-Lore below) and reprinted in Folk-Lore, Sept. 1890. It is very corrupt, both girls being called Kate, and I have had largely to rewrite.”1 Andrew Lang in Folk-Lore included the following citation: “Collected by Mr. D. J. Robertson of the Orkneys. Printed in Longman’s Magazine, vol. xiii.”2

Here is the Joseph Jacobs retelling:

Once upon a time there was a king and a queen, as in many lands have been. The king had a daughter, Anne, and the queen had one named Kate, but Anne was far bonnier than the queen’s daughter, though they loved one another like real sisters. The queen was jealous of the king’s daughter being bonnier than her own, and cast about to spoil her beauty. So she took counsel of the henwife, who told her to send the lassie to her next morning fasting.

So next morning early, the queen said to Anne, “Go, my dear, to the henwife in the glen, and ask her for some eggs.” So Anne set out, but as she passed through the kitchen she saw a crust, and she took and munched it as she went along.

When she came to the henwife’s she asked for eggs, as she had been told to do; the henwife said to her, “Lift the lid off that pot there and see.” The lassie did so, but nothing happened. “Go home to your minnie and tell her to keep her larder door better locked,” said the henwife. So she went home to the queen and told her what the henwife had said. The queen knew from this that the lassie had had something to eat, so watched the next morning and sent her away fasting; but the princess saw some country-folk picking peas by the roadside, and being very kind she spoke to them and took a handful of the peas, which she ate by the way.

When she came to the henwife’s, she said, “Lift the lid off the pot and you’ll see.” So Anne lifted the lid but nothing happened. Then the henwife was rare angry and said to Anne, “Tell your minnie the pot won’t boil if the fire’s away.” So Anne went home and told the queen.

The third day the queen goes along with the girl herself to the henwife. Now, this time, when Anne lifted the lid off the pot, off falls her own pretty head, and on jumps a sheep’s head. So the queen was now quite satisfied, and went back home.

Her own daughter, Kate, however, took a fine linen cloth and wrapped it round her sister’s head and took her by the hand and they both went out to seek their fortune. They went on, and they went on, and they went on, till they came to a castle. Kate knocked at the door, and asked for a night’s lodging for herself and a sick sister. They went in and found it was a king’s castle, who had two sons, and one of them was sickening away to death and no one could find out what ailed him. And the curious thing was that whoever watched him at night was never seen any more. So the king had offered a peck of silver to any one who would stop up with him. Now Katie was a very brave girl, so she offered to sit up with him.

Till midnight all went well. As twelve o’clock rang, however, the sick prince rose, dressed himself, and slipped downstairs. Kate followed, but he didn’t seem to notice her. The prince went to the stable, saddled his horse, called his hound, jumped into the saddle, and Kate leapt lightly up behind him. Away rode the prince and Kate through the greenwood, Kate, as they pass, plucking nuts from the trees and filling her apron with them. They rode on and on till they came to a green hill. The prince here drew bridle and spoke, “Open, open, green hill, and let the young prince in with his horse and his hound,” and Kate added, “and his lady behind.”

Immediately the green hill opened and they passed in. The prince entered a magnificent hall, brightly lighted up and many beautiful fairies surrounded the prince and led him off to the dance. Meanwhile, Kate, without being noticed, hid herself behind the door. There she saw the prince dancing, and dancing, and dancing, till he could dance no longer and fell upon a couch. Then the fairies would fan him till he could rise again and go on dancing.

At last the cock crew, and the prince made all haste to get on horseback; Kate jumped up behind, and home they rode. When the morning sun rose they came in and found Kate sitting down by the fire and cracking her nuts. Kate said the prince had a good night; but she would not sit up another night unless she was to get a peck of gold. The second night passed as the first had done. The prince got up at midnight and rode away to the green hill and the fairy ball, and Kate went with him, gathering nuts as they rode through the forest. This time she did not watch the prince, for she knew he would dance, and dance, and dance. But she saw a fairy baby playing with a wand, and overheard one of the fairies say: “Three strokes of that wand would make Kate’s sick sister as bonnie as ever she was.” So Kate rolled nuts to the fairy baby and rolled nuts till the baby toddled after the nuts and let fall the wand, and Kate took it up and put it in her apron. And at cock crow they rode home as before, and the moment Kate got home to her room she rushed and touched Anne three times with the wand, and the nasty sheep’s head fell off and she was her own pretty self again. The third night Kate consented to watch, only if she should marry the sick prince. All went on as on the first two nights. This time the fairy baby was playing with a birdie; Kate heard one of the fairies say: “Three bites of that birdie would make the sick prince as well as he ever was.” Kate rolled all the nuts she had to the fairy baby till the birdie was dropped, and Kate put it in her apron.

At cockcrow they set off again, but instead of cracking her nuts as she used to do, this time Kate plucked the feathers off and cooked the birdie. Soon there arose a very savoury smell. “Oh,” said the sick prince, “I wish I had a bite of that birdie,” so Kate gave him a bite of the birdie, and he rose up on his elbow. By-and-by he cried out again: “Oh, if I had another bite of that birdie!” so Kate gave him another bite, and he sat up on his bed. Then he said again: “Oh! if I but had a third bite of that birdie!” So Kate gave him a third bite, and he rose hale and strong, dressed himself, and sat down by the fire, and when the folk came in next morning they found Kate and the young prince cracking nuts together. Meanwhile his brother had seen Annie and had fallen in love with her, as everybody did who saw her sweet pretty face. So the sick son married the well sister, and the well son married the sick sister, and they all lived happy and died happy, and never drank out of a dry cappy.

And here is the version Lang published, collected by D. J. Robertson:

Once upon a time there was a king and a queen, as in many lands have been. The king had a dochter, Kate, and the queen had one. The queen was jealous of the king’s dochter being bonnier than her own, and cast about to spoil her beauty. So she took counsel of the henwife, who told her to send the lassie to her next morning fasting. The queen did so, but the lassie found means to get a piece before going out. When she came to the henwife’s she asked for eggs, as she had been told to do; the henwife desired her to “lift the lid off that pot there” and see. The lassie did so, but naething happened. “Gae hame to your minnie and tell her to keep her press door better steekit,” said the henwife. The queen knew from this that the lassie had had something to eat, so watched the next morning and sent her away fasting; but the princess saw some country folk picking peas by the roadside, and being very affable she spoke to them and took a handful of the peas, which she ate by the way.

In consequence, the answer at the henwife’s house was the same as on the preceding day.

The third day the queen goes along with the girl to the henwife. Now, when the lid is lifted off the pot, off jumps the princess’s ain bonny head and on jumps a sheep’s head.

The queen, now quite satisfied, returns home.

Her own daughter, however, took a fine linen cloth and wrapped it round her sister’s head and took her by the hand and gaed out to seek their fortin. They gaed and they gaed far, and far’er than I can tell, till they cam to a king’s castle. Kate chappit at the door and sought a “night’s lodging for hersel’ and a sick sister.” This is granted on condition that Kate sits up all night to watch the king’s sick son, which she is quite willing to do. She is also promised a “pock of siller” “if a’s right.” Till midnight all goes well. As twelve o’clock rings, however, the sick prince rises, dresses himself, and slips downstairs, followed by Kate unnoticed. The prince went to the stable, saddled his horse, called his hound, jumped into the saddle, Kate leaping lightly up behind him. Away rode the prince and Kate through the greenwood, Kate, as they pass, plucking nuts from the trees and filling her apron with them. They rode on and on till they came to a green hill. The prince here drew bridle and spoke, “Open, open, green hill, an’ let the young prince in with his horse and his hound,” and, added Kate, “his lady him behind.”

Immediately the green hill opened and they passed in. A magnificent hall is entered, brightly lighted up, and many beautiful ladies surround the prince and lead him off to the dance, while Kate, unperceived, seats herself by the door. Here she sees a bairnie playing with a wand, and overhears one of the fairies say, “Three strakes o’ that wand would mak Kate’s sick sister as bonnie as ever she was.” So Kate rowed nuts to the bairnie, and rowed (rolled) nuts till the bairnie let fall the wand, and Kate took it up and put it in her apron.

Then the cock crew, and the prince made all haste to get on horseback, Kate jumping up behind, and home they rode, and Kate sat down by the fire and cracked her nuts, and ate them. When the morning came Kate said the prince had a good night, and she was willing to sit up another night, for which she was to get a “pock o’ gowd.” The second night passes as the first had done. The third night Kate consented to watch only if she should marry the sick prince. This time the bairnie was playing with a birdie; Kate heard one of the fairies say, “Three bites of that birdie would mak the sick prince as weel as ever he was.” Kate rowed nuts to the bairnie till the birdie was dropped, and Kate put it in her apron.

At cockcrow they set off again, but instead of cracking her nuts as she used to do, Kate plucked the feathers off and cooked the birdie. Soon there arose a very savoury smell. “Oh!” said the sick prince, “I wish I had a bite o’ that birdie,” so Kate gave him a bit o’ the birdie, and he rose up on his elbow. By-and-by he cried out again, “Oh, if I had anither bite o’ that birdie!” so Kate gave him another bit, and he sat up on his bed. Then he said again, “Oh! if I had a third bite o’ that birdie!” So Kate gave him a third bit, and he rose quite well, dressed himself, and sat down by the fire, and when “the folk came i’ the mornin’ they found Kate and the young prince cracking nuts th’gether.” So the sick son married the weel sister, and the weel son married the sick sister, and they all lived happy and dee’d happy, and never drank out o’ a dry cappy.

When you compare the two, you can easily see some of the changes Jacobs made in his retelling. From his notes, we know Jacobs thought the version Lang published needed to be rewritten. But what about my version? Why is it so different from the Jacobs version?

I was familiar with this tale and attempted retellings of it for over twenty years before I managed to retell it in a way that both pleased me and held the attention of my listeners. I loved the story’s positive portrayal of the relationship between stepsisters. However, for years, I kept wondering why Kate’s mother wanted to destroy Annie. The explanation given in both Jacobs’s and Lang’s versions, that the king’s daughter was bonnier than the queen’s daughter, seemed inadequate motivation. In my retelling attempts, Kate’s mother’s actions never felt truly believable.

Yes, I know that one girl’s being prettier than the other seems reason enough for the actions of the stepmother in the previous story, “Rawhead and Bloody Bones,” a recent addition to my telling repertoire, and I’ve been asking myself why. What’s the difference? Perhaps my mind accepts the jealousy motivation there because in that story the girls do have equal opportunity for success, and they act alone. In “Kate Crackernuts” Annie doesn’t have a chance. The story is not structured as an equal opportunity tale. She is powerless to escape her stepmother’s evil plans. She’s obedient, she’s kind, but it’s simply not enough. Without Kate’s help, Annie is doomed.

Yes, I also know both stories are fairy tales, so none of it really happened, but for me to tell a story well, the characters have to behave in a manner that I can believe throughout the story. I want to be able to talk about them with the same ease with which I could tell about something that happened to me. “She’s prettier, so I’ll destroy her” never quite satisfied my need for a believable motivation for Kate’s mother.

Then real life provided additional insight. In 1991 a Texas mother was found guilty of attempting to hire a hit man to kill the mother of her daughter’s cheerleading rival.3 The mother wanted to improve her daughter’s chances of making the cheerleading team by creating such turmoil in the other girl’s life that she would be too upset to try out. Hearing about this incident immediately reminded me of the relationship between Kate Crackernuts and her mother. Both mothers wanted to help their daughters, but their actions reveal a lack of confidence in a daughter’s ability to succeed in the world. This real-life incident sent me back to the folktale with a deeper understanding of the possible fears and doubts motivating Kate’s mother and even more admiration for Kate’s intelligence and courage.

In addition, both the Lang and Jacobs versions begin with the narrator talking about the king and queen, and then telling about the queen setting up the spell with the henwife. Beginning the story with the king and queen simply did not work for me. I wanted to meet the girls right away and learn more about them. Once I changed the narrator’s focus to Kate and Annie from the very beginning of the tale, their journey became clearer to me, and I found much more pleasure in recounting the tale. Yes, Kate’s mother still makes horrible decisions, but the story I am telling is of Kate, a girl who, even though lacking the guidance of a mother who accepts her strengths and helps her nurture them as she grows up, still manages to know herself, trust herself, and succeed.

And no, I’m not saying getting married is the mark of success. I count Kate successful because she charts her own course. She does what is needed to secure her finances, and it is she who sets the terms for marriage in her bargaining with the king. That Kate sets her own marriage terms is not my invention. It was included in Jacobs’s and Lang’s versions and was one of the details I found appealing from my first contact with the tale.

In working with this story over the years, I created word outlines, time lines, and story maps (stick figure cartoon-like drawings) as part of my story learning process.

Here’s a sample from a word outline:

Beginning—Kate’s mother and Anne’s father married.

Kate & Anne like each other

Kate’s mother worries that Anne is prettier, more graceful, talented—dancing and needlework? So, she decides to destroy her.

Kate’s mother sends Anne to henwife for eggs.

1st time—Anne eats bread crust—nothing happens.

2nd time—Anne sees gardeners, give peas, eats—nothing happens

3rd time—Kate’s mother goes along

Anne’s head replaced with sheep’s head

Mother overjoyed

Here? Middle?

1. Mother returns with Anne. Kate takes Anne and leaves.

2. Kate and Anne find palace of sick prince, reward for spending the night watching him

Kate decides to try for reward (basket of silver)

Kate learns he is enchanted by fairies who make him dance all night—earns silver

2nd night (for basket of gold)

Kate learns 3 taps of wand will cure sister

rolls nuts to take wand from baby

cures sister upon return to palace

Here’s a sample from the time line:

Ages 7–9? Kate’s father and Anne’s mother die.

Ages 11–13? Kate’s mother and Anne’s father marry.

Ages 13–15? Kate’s mother notices differences between her daughter and Anne and becomes concerned, worried, then obsessed enough to plan Anne’s destruction.

Story begins here: 1st day of story—Kate’s mother contracts with henwife for spell on Anne.

Day 1—sends Anne to henwife but Anne eats crust.

Day 2—sends Anne to henwife but Anne eats peas from gardners.

Day 3—takes Anne to henwife, spell works, Anne’s head replaced with sheep’s head.

Same day—Kate’s mother returns with Anne. Kate wraps Anne’s head in cloth and leads Anne away from home.

? _______ (How long?) the two girls journey (Must take long enough to reach area with another king; yet not so long that they look so raggedy from their journey they are not welcomed)

1st night—Kate stays with sick prince; collects nuts as they journey together; learns nature of spell fairies have placed on him; earns silver.

Next morning—Kate is sitting at fireplace cracking nuts, given silver, makes deal for 2nd night for gold.

As you can see from these excerpts, the word outline and time line, while similar, are not exactly the same. When I create a word outline, I focus on the sequence of events in the story. When I create a time line, I focus more on the passage of time within the story, not just the order of events. Both are learning tools, created while I am working to learn the story to help me see how events might flow.

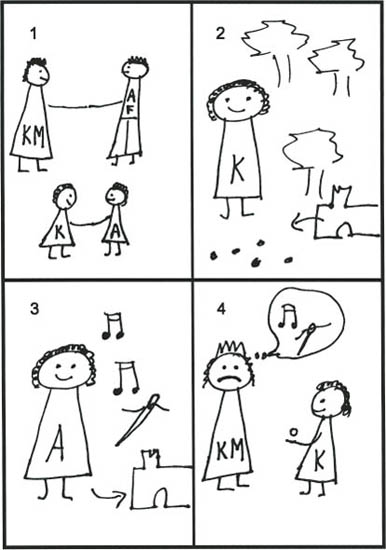

I also made a story map for “Kate Crackernuts” using cartoon-like stick figure drawings. When I create story maps, I continually ask myself: What is the next picture I need to create for my audience? I’m also creating the map as I’m striving to understand the story, so it keeps changing and changing as my understanding of the story changes. My “Kate Crackernuts” story map is pretty much indecipherable by anyone but me. And that’s okay, because I’m the one I created it for!

Okay, I imagine you have the idea. I draw pictures, not great art, but stick figures, as I’m thinking my way through the story. The map for this story continues for thirty-seven panels, with some containing words (Panel 32 says “repeat panels 21–25”) to note repeated events. As I work, I notice when I need to return to the text because I can’t recall what comes next. I consult the text only as much as necessary to keep myself moving through the story. I do not consult the text for every step as I create my story maps because I’m working to discover how I picture the story, not trying to create a rough duplication of images I could glean from the text. It is the process of drawing the map that contributes to my learning by making me think through the story visually instead of with words.

Story Map

Panel 1: Four stick figures, labeled KM (for Kate’s Mother), AF (for Annie’s father), K (for Kate), and A (for Anne). A line connects Kate’s mother and Annie’s Father. Another line connects Kate and Annie.

Panel 2: Kate surrounded by trees with circles representing nuts underneath them. Off to the side is a palace with an arrow pointing away from it (to emphasize that this character spends her time outside).

Panel 3: Annie surrounded by musical notes and a needle and thread. Off to the side is a palace with an arrow pointing toward it (to show this character spends her time inside).

Panel 4: A frowning Kate’s Mother stands on the left. From her head, a cartoon thought bubble with musical notes and a needle and thread inside. Facing her, a smiling Kate holds a nut in her hand.

I also ask and answer questions as part of my work, such as:

• Kate’s mother notices Kate and Annie are different, but what does she see and what does she hear that leads her to become so obsessed she is willing to destroy Annie?

• What is Kate’s mother so afraid of?

• Why don’t the fairies know Annie is cured and wand is missing if they know Annie is at the palace?

• Why don’t they catch on and stop Kate—or do they know she is listening?

• Or do they just not check the palace every day?

• Or, is Kate listening to different fairies who are talking about different things, and the fairies themselves have not communicated new information to all before Kate secures the yellow birdie?

And I make notes of my observations, such as:

• Fasting is important to put spell on Annie, but eating is important to break spell on Prince.

• The henwife says “The pot won’t boil if the fire is away” to mean the spell is your idea so you need to be here—you are the fire. On this day the henwife doesn’t even ask if Annie has eaten, she just gives the message?

I don’t usually save the work I create while working on learning a story. I just happen to still have the work from “Kate Crackernuts” because at about the time I was finished using my outline, time line, and map, I was hired to teach a full-day workshop on learning to retell folktales. The workshop coordinator wanted participants to be able to attend the workshop having already selected a story and completed some of the work of learning it before they arrived. Because I did not want participants to fall into the common misconception of believing learning a story meant memorizing the words, we mailed participants copies of my learning work as examples, and asked them to arrive with outlines, time lines, and maps of their chosen stories. Seeing my examples helped the workshop participants really believe my advice that the only way they could create unacceptable outlines, time lines, or maps for their story would be to simply not create them at all. So, I saved my work and have used it as preparation examples for workshop participants in subsequent folktale retelling workshops.

That I do the sort of work I’ve described—creating outlines, time lines, story maps, asking questions, making observations, and more—while pondering the story I want to retell does not make me unique among storytellers. This is the type of work many tellers who “learn the story, not the words” do as they come to know a story they wish to retell. This is also the sort of work I first learned about in the storytelling residencies with Laura Simms.4

Eventually I reach my goal of becoming so familiar with the characters and the story of what happened to them that I can more fully imagine this story from their lives. When you compare my version with the Jacobs version, it is pretty clear I’ve imagined more details of the girls’ lives than the Jacobs text provided. Because I wanted to focus on Kate and Annie’s story, I provide more detail so my audience can more fully picture how these two stepsisters, while very different from each other, show love and respect for one another. And, as mentioned earlier, my interest in Kate’s mother’s motivation led me to more descriptions of what she saw and felt as she watched Kate and Annie grow up.

I’ve also made smaller deliberate changes. I changed the peck basket to a pound. Maybe you’ve bought something by the peck recently, but I haven’t. When I considered using simply “basket,” I kept imagining Kate negotiating the size of the basket before agreeing to her task, and there I was—back to “peck.” I dropped the hound because I simply could not picture Kate and the dog at the home of the fairies without also seeing the dog’s actions revealing her presence. As for the yellow birdie? Why yellow? I haven’t a clue, although I’m fairly sure I harbor no animosity toward Tweety!

In addition to thinking and imagining beyond the text of a story, it’s not unusual for me to also think about events in characters’ lives that I know I’ll never include in my telling of the tale: How did Kate’s mother explain the missing girls to Annie’s father? Did she tell the truth or lie? How did Annie’s father react to these events? Did the girls invite the parents to their wedding? Could Kate and Annie ever forgive Kate’s mother? Is any reconciliation ever possible after such events?

I owe a big thank you for my ending of the story to Candy Kopperud, the library services coordinator at Palmer Public Library in Palmer, Alaska. Until Candy heard the story, I had ended it with a reference to the weddings and a happily ever after. After she heard the story, Candy told me she had been sure I was going to mention dancing at the weddings and how Kate’s prince did not like dancing, but did not know why. Oh my! I knew an improved ending when I heard one, and with Candy’s permission I’ve incorporated her idea into the ending ever since.5

I don’t know what happened to the would-be Texas cheerleader, but her mother was granted probation in 1997. The young woman was thirteen when her mother was convicted and seventeen when her mother was granted probation.6 By now, she is an adult. Like Kate Crackernuts, I hope she managed to know and trust herself and chart her own successful path.