Bet big to lose big

Mistake 11: misusing leverage and margin

Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.

Archimedes

Perhaps one of the most abused and least understood trading tools are the twin concepts of leverage and trading on margin, often referred to as gearing. When used effectively and with a complete understanding of the outcomes that can occur as a result of their use, both negative and positive, leverage and margin are wonderful ways to increase returns and enhance the performance of a well-researched and robust trading system. When not fully understood and used within the realms of reality the results can be disastrous. The differentiation between the two is important, as the concepts are very different, and need to be fully understood. Without a realistic understanding of these concepts and their implementation, the outcomes can be horrendous.

Margin or leverage — what’s the big deal?

Australian trader, educator and author Christopher Tate explains the difference between leverage and margin:

I regard leverage and margin as two different concepts. Leverage is the use of a financial instrument such as a futures or options contract to control a larger amount of product than might have otherwise been possible if you were directly trading the underlying instrument.

For example, if I buy a BHP $28 option contract for $1, I effectively have control over 1000 BHP shares for an outlay of $1000 plus costs. If I were to go into the market to buy 1000 BHP at $28 it would cost me $28 000 plus costs. The purchase of the option contract has given me the same exposure but for only $1000. This is the basis of leverage—a small outlay enables you to control a large amount of a given instrument. Leverage is also sometimes erroneously referred to as ‘gearing’.

Trading on margin or using a margin loan is slightly different but achieves the same outcome. It enables traders to control a larger amount of product than they might otherwise have been able to.

The familiar example of margin trading is the notion of buying a house. All house purchases—except those rare exceptions where someone purchases a house outright for cash—are margin transactions. The homeowner puts up a margin (the deposit) and the rest is borrowed. For example, if I were buying a house for $500 000, I would put up a deposit of 20 per cent or $100 000 and would borrow the rest. With my $100 000 deposit I control a financial asset worth $500 000.

So margin refers to the use of borrowed funds to effectively increase your buying power. If we were to put this in the context of a stock trader using a margin loan account then they might purchase a basket of shares using borrowed funds. For example, if I wanted to establish a portfolio with $30 000, I might seek to borrow an additional amount of money to increase my purchasing power and the amount of product (shares) I controlled. If I limited my selection of shares to stocks that had a loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) of 70 per cent, I would be able to gross my total portfolio up to $100 000. My $30 000 initial margin or deposit is now controlling $100 000 worth of shares.

It is this ability to increase your potential returns that makes both leverage and margin so attractive to traders of all sizes. The use of margin is universal in the trading world. Everyone from mum-and-dad investors to giant hedge funds will use borrowed funds to increase the size of their potential gains. In fact, much of the turmoil in the current market has come about because of forced liquidations of margined positions.

One of the most extreme examples of what can happen to a share price when forced liquidations occur is ABC Learning Centres, whose executives and directors all had margined exposure to their own stock price. As the stock price fell, those with margined positions either had to meet their margin calls or face the forced liquidation of their shares. As shares were forcibly liquidated the price fell, generating more margin calls and further forced liquidations. An awful feedback cycle of falling share prices and forced liquidations triggered even further falls, which triggered further liquidations. The cycle continued until the stock price imploded. Such a disaster is a strong call for the full disclosure by companies of any margin facilities that their directors or staff may have.

The major benefit of using leverage and/or trading on margin is the increased purchasing power of the trader’s available capital. As shown in the example above, relatively small amounts of capital can be used to have access to much larger position sizes than would be available to traders if they were to use only the capital or funds they had available. In the futures markets, the same leverage rules apply where significant amounts of a commodity or equity index can be traded by lodging a margin amount with the broker and then trading much larger dollar amounts of the contract. For example, the margin requirement for a futures contract for wheat at the time of writing was US$3375 on a contract with a face value of around US$31 500. This means that the trader is able to trade a US$31 500 face value wheat contract by lodging just US$3375 as margin with the Chicago Board of Trade via their personal futures broker. The result is the possibility to greatly increase returns. At $50 per point, if the price increases by 10 points and the trader is long, a profit of $500 has been made. Having lodged US$3375 to participate in the trade, this represents a return of just under 15 per cent. If the trader had to use the full US$31 500 of the contract’s face value to participate in the trade, this would result in a return of a little over 1.5 per cent on the total capital outlaid for the trade. If we assume our trader has a US$50 000 account and has traded conservatively with just one contract, a return on equity of 1 per cent has been achieved from this trade ($500 profit in a $50 000 account). This example shows what happens in the event that the trade has a favourable outcome.

Of course, the reverse is true if the trade is a loser. In the example above, if the trader suffers a loss of 10 points or $500, this gives a negative return of just under 15 per cent on the amount of margin required for the trade, and around 1 per cent of the trader’s overall trading capital. The problem arises when traders are over-leveraged in their account and have not given adequate consideration to what can happen in the event of a major move against their open trade position.

Let’s assume that our trader has used the leverage ability of futures trading aggressively, ill-informed and with total lack of understanding of what can go wrong. Like many, this trader uses the available leverage inappropriately and trades too many contracts, through a false sense of self-belief that he is the next great wheat futures trader, or simply by the fact that he is ill-informed or unaware as to what can go wrong. Our trader steps up to the plate and decides to buy 10 contracts, thus using US$33 750 ($3375 margin per contract × 10 contracts) of his available capital to lodge as margin for the trade. Having entered the trade the trader then finds that a few days later the position has moved against him to the point where he has been stopped out of the trade. Unfortunately, the market has ‘gapped’ through the trader’s stop-loss price. Instead of being stopped out with a 10 point loss per contract ($500), the trader realises a loss of 20 points per contract ($1000) as a result of the gap move against the position. The total loss is now US$10 000 ($1000 per contract × 10 contracts). Our trader has suffered a 20 per cent loss in total trading capital, and is left feeling beaten up, and hopefully somewhat wiser from the experience.

While this example is a significant loss, it probably wouldn’t be considered debilitating. However, there are countless examples of traders using much higher levels of margin or leverage that have resulted in them completely wiping out their trading accounts. For many share and derivatives traders, leverage is a double-edged sword. On one hand it allows us to generate large percentage returns on our available capital. It can also magnify losses and add a larger element of risk for traders who don’t fully understand or comprehend the ramifications of trading using margin. Many inexperienced, undercapitalised and underprepared CFD traders have no doubt felt the wrath of the markets when they have been overexposed to adverse market movements. Trading using the margins available from the CFD providers has enabled many people to begin trading using very small amounts of start-up capital. They have then leveraged up these accounts while not fully understanding the consequences of their actions, and have suffered accordingly when the market has moved against them.

Many of these traders had little or no understanding of the consequences of their actions until they experienced the violent correction that occurred in worldwide equity markets during 2008. The following example shows the effect of overusing leverage.

Example 1

Trader Joe opens a CFD trading account with $10 000. He begins trading CFDs on the top 20 listed Australian shares with a leverage of 10:1 or 10 per cent. This allows him to take positions with 10 times the face value of the position while only having to lodge a 10 per cent margin. Joe incorrectly believes that his account gives him the ability to have open positions worth $100 000. He then goes about buying CFDs based on this premise. Unfortunately for Joe, just as he gets ‘his’ $100 000 spent, the market crashes and his CFD positions are all down by over 15 per cent or $15 000. Joe’s trading account is wiped out. He has lost his initial $10 000, plus he still owes the CFD provider an extra $5000. He is forced to sell out of his open positions and still has to find the extra cash to pay the CFD provider. Joe also signed up and paid his initial $10 000 using his credit card, so he now also has a debt on his card to service. And the CFD provider is able to take the extra $5000 from Joe’s credit card as well. Joe’s dreams are shattered. He has lost his initial capital plus a bit extra that he can’t afford to lose—and he has a debt. He thinks trading is for idiots and he hasn’t told his wife yet!

Share trading on margin (margin loans)

Just as margin can increase the potential size of a trader’s returns it can also increase the size of one’s losses. This is a point that is often overlooked in the glossy marketing material that potential investors receive.

Let’s return to our share investor with a $100 000 portfolio which only has $30 000 equity in it. This portfolio has $70 000 worth of debt or margin attached to it. The provider of the loan facility will always want its money returned irrespective of market conditions. To make certain that this always occurs, the lender will impose what is known as an LVR. The LVR not only stipulates how much can be borrowed, but also sets the trigger point for any margin call.

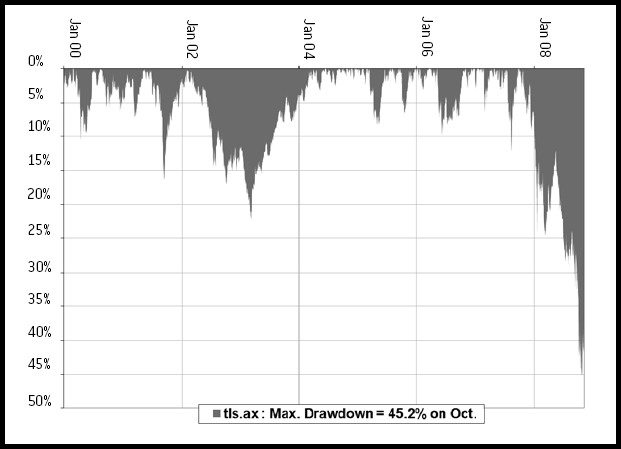

Our example tells what effect a fall in the value of our portfolio will be and how much up of a top-up or margin call will be required to stabilise the portfolio at the prescribed LVR.

Let’s assume that the value of our portfolio falls to $90000 from a starting value of $100000.

To bring our level of borrowing back into line with what is required, we would have to add $10 000 to the account.

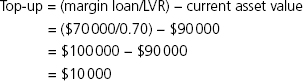

It might seem unlikely that our portfolio would draw down 10 per cent on a regular basis, but let’s assume that our portfolio has a high correlation with the S&P ASX200 Index. By making this assumption we can get an idea of how often we might be faced with such a drawdown.

The chart in figure 11.1 (overleaf) looks at the number of drawdowns that have occurred on the S&P ASX200 Index since January 2000. As you can see, the market has dropped by 10 per cent or more about once per year. It should also be noted that this period includes one of the largest bull markets in history. So you need to be prepared for the possibility that the market will fall and you will suffer a margin call. Such a chart acts as a dose of realism against the overly optimistic projections given by brokers and financial planners when they promote products such as margin loans.

Figure 11.1: chart of ASX200 drawdown analysis

It could be argued that the investor might not have a portfolio that is highly correlated with the underlying index. This is a fairly weak argument because the universe from which shares can be purchased using a margin loan is quite small and is largely drawn from the major indices. Hence, they have a reasonable correlation with the underlying index.

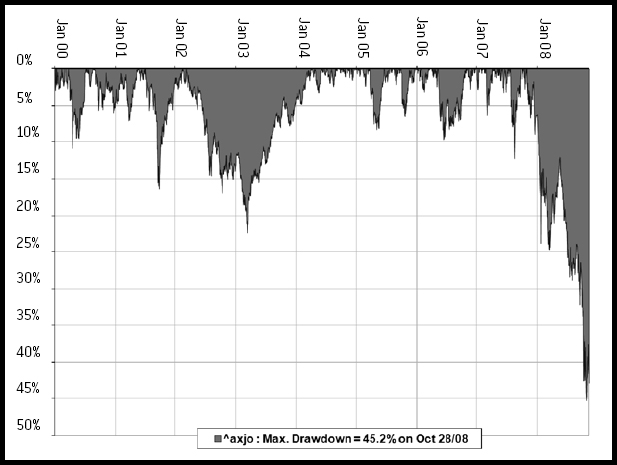

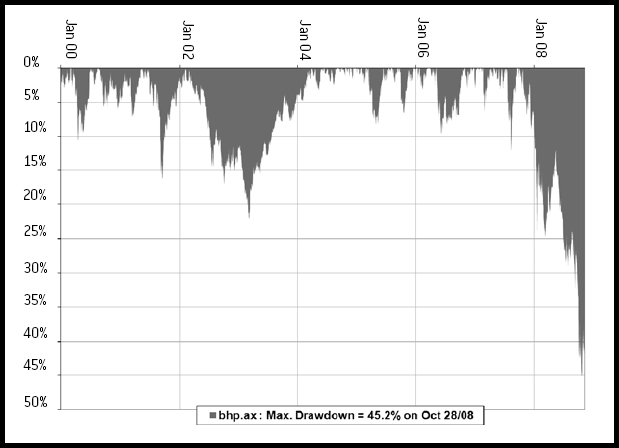

However, it is an interesting exercise to look at the potential drawdown for two of the most popular Australian shares that are included in margin loans: BHP Billiton (BHP), shown in figure 11.2 (overleaf), and Telstra (TLS), shown in figure 11.3 (page 119).

Figure 11.2: BHP drawdown analysis

Figure 11.3: TLS drawdown analysis

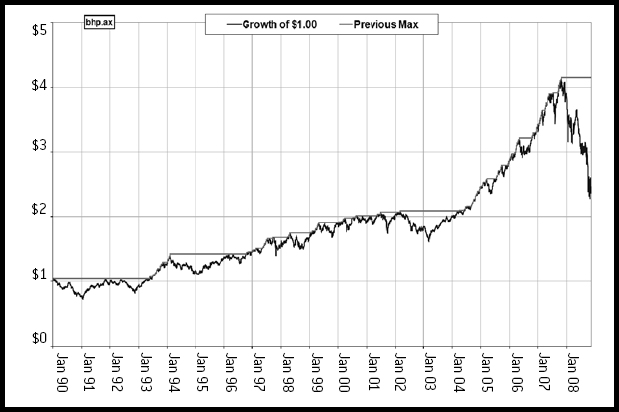

Each of these charts show that stocks can and do fall. It is common among brokers to believe that the law of gravity has been repealed and they express great surprise when things go down. Whenever this does occur, investors generally get the old chestnut of ‘good shares always get better’. Unfortunately the market and the person providing the margin loan beg to differ. Consider the chart in figure 11.4 (overleaf) which represents the value of $1 invested into BHP in 1990.

Figure 11.4: growth of a $1 investment in BHP since 1990

Now we need to view figure 11.4 somewhat cynically. Investors’ attention is immediately drawn to the right-hand side of the chart when the value of BHP moved up strongly during the bull market. However, that is not what potential investors should be looking at. They should be looking at the number of times BHP was stagnant for several years and, as per our drawdown analysis, the number of times the stock dropped to such a point that it would trigger a margin call. Investors are often overly optimistic as to their ability to ride out such periods, particularly when they are being reminded of their decreasing equity each day.

For the reasons outlined earlier, many opt not to borrow the full amount of their portfolio but rather keep their borrowings to a more manageable figure. This is done either by borrowing less, using more equity to establish the facility, or a combination of both. For example, if we change the balance to, say, 50 per cent equity and 50 per cent borrowings, the portfolio would have much greater room to move before we were hit with a margin call.

It also needs to be noted that since this is a loan it will need to be paid back and you need to be certain you can pay it back. You need to take into account the following considerations.

- The security ratio assigned to an asset may change over time. This means that you may have to suddenly top up your account with extra funds to compensate. However, by being conservative, you can build in a buffer against this.

- Interest rates may rise substantially during the time of the loan. This issue can be dealt with either by making certain you have surplus cash flow to deal with the additional costs you are incurring, or by fixing the interest rate at a given level. You should ensure that you have enough surplus cash flow to absorb interest payments. You could consider fixing the interest rate on some (or all) of your margin loan to offer protection.

- The income from your investments may fall, leaving you with a cash flow shortage. You should think about ensuring that you have enough surplus cash flow to cover any income shortfall.

It is a wonderfully interesting phenomenon that share trading on margin through the use of margin loans reaches its zenith as bull markets near their peaks. Many would-be traders and investors are lured into them on the promise of participating in the supposedly never-ending growth of equity prices by using only a small amount of their own capital, and borrowing the balance at ‘attractive’ interest rates. However, it all ends in tears when the market tanks and the trader/investor is left to watch as share prices slide, decimating portfolios and, more often than not, resulting in a margin call.

A margin call is a demand for additional funds by the company providing you with the loan facility. Margin calls traditionally result from a fall in the value of the investor’s portfolio, although occasionally they may result from a change in the level of borrowing permitted against a given stock.

It is important to note that this is a demand for additional funds—it is not a request to be taken lightly. Investors generally have 24 hours to respond to the call for additional equity. If the call is not met then the loan provider can and will begin selling down the portfolio to reduce the value of the exposure and to bring the portfolio back into line with their lending guidelines. A forced sell-down should be avoided if possible because the lender will simply issue the instruction to begin selling your holdings at market. If any of these orders hit a thinly traded market, then the prices you achieve during the sell-down may be much worse than if you had undertaken the sell-down yourself in a controlled manner.

Allowing a third party to take control of your investments also demonstrates an unwillingness to deal with the issues at hand. Unfortunately, denial is not an investment strategy and investors should always look to be in control of their financial future. This matter should never be left to a third party since they will have only their interests at heart, not yours.

The simplest way to avoid persistent margin calls is to borrow conservatively. Just because you may be able to gear to a certain level does not mean that you need to gear yourself to this level. Borrowing limits are not compulsory—you may gear your portfolio in the manner that best suits you.

There are only two ways to deal with a margin call once it has been received:

1. Pay up the amount required.

2. Sell down part of the portfolio.

Investors have extremely limited options once the call has been received. It is far better to have some form of defensive plan in place that avoids the calls being received.

Using leverage or margin in trading requires a thorough understanding of both the positive and negative consequences that gearing can create. Ignoring it is not an option, nor is believing that the negative outcomes will not happen to you. They will! It is vitally important to thoroughly understand the implications of using any level of gearing in your trading business. Properly understood and used, gearing can and will substantially increase the returns available to traders and investors. Gearing up a robust and profitable trading system or strategy has the potential to make great results become outstanding. Gearing up a poorly performing system or trading strategy will only serve to wipe it (and you) out quicker than if it were not geared.

Use it wisely and it will be your friend; use it unwisely and it will be your worst enemy.

Christopher Tate is a trading veteran of 30 years. He has had an extraordinary impact on thousands of traders. Bestselling author of The Art of Trading and The Art of Options Trading in Australia, his brutally honest approach and meticulous pursuit of excellence qualify him as Australia’s foremost derivatives trading expert. In this chapter, Christopher explained leverage and margin and the dangers of misusing them.

Christopher has seen all types of markets, traded every instrument available, and profited in every one of them. He is in constant demand for his world-renowned mentor program and keynote speaking skills. Christopher has the skills to help you to radically jumpstart your returns. Unlike most other trainers who teach only theory, Christopher is one of the few people who truly understand what does and does not work in the share market. Register at <www.tradinggame.com.au> for a pack of free trading goodies to help you trade profitably and safely.