Chapter 1: Common Types of Stone and Rock

Many people think of stone as large boulders that create cliffs, buttes, and mountaintop ranges. Many may also think of landscaping stone in pleasant, rounded shapes used in flower beds and front entryways. Rock and stone are considered the same thing, but it is accepted that rock is stone in its purest form — without any smoothing, cutting, or shaping. Stone is the term used when rock is smoothed, chipped, or textured for landscaping or building. When you are looking to build with stone, you will find it comes in many shapes, weights, textures, colors, and sizes. This chapter describes the types of stone primarily used for architectural purposes and the unique properties of each.

Sedimentary Rock

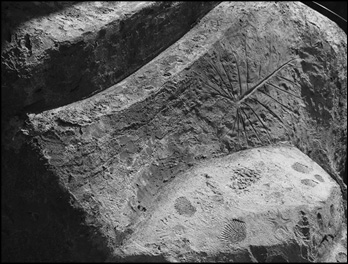

Sedimentary rock is one of the three main rock groups — along with igneous and metamorphic — and is formed when remains of other rocks and biological activities, such as leaf and animal matter decomposition, known as diagenesis, are compressed. Common types of sedimentary rocks include chalk, coquina, limestone, sandstone, and shale. Chalk is not used as building material because it is very soft, but it is quarried to use in the manufacturing of writing chalk and used along with kaolin, a type of clay, in cosmetics and ceramic pottery. Most limestone contains fossil imprints because of diagenesis, and often these imprints are integrally maintained because sedimentary rock is not formed under the high temperatures and pressure that igneous and metamorphic rock are formed under. Sedimentary rock is formed very slowly over time when elements like broken shells, which contain a high amount of calcium and lime; plant materials; sand; grit; and other organic materials, are washed into rivers, lakes, oceans, and craters and these elements experience continuous pressure that climactic changes in earth core temperature or the continuing weight of additional elemental materials can cause. Over thousands of years, the bottom layers of washed away elements become rock.

The Earth’s layers consist of an upper layer of sedimentary rock, a middle layer of igneous rock, and an inner layer of metamorphic rock.

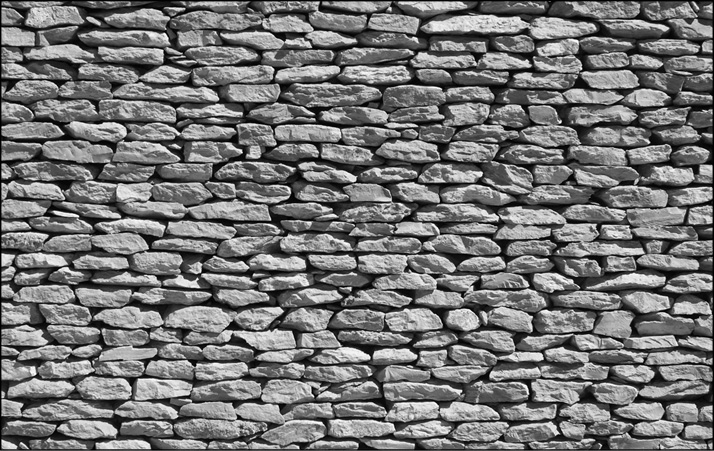

Sedimentary rock forms a crust over the igneous and metamorphic rock and is much softer and easier to build with. Limestone and sandstone are the easiest types of stone to cut and shape for most building projects. These two stones reflect light and are used in many countries, such as Egypt and Syria, for just that purpose. Different types of sandstone and limestone range from fine-grained and hard to coarse-grained and crumbly. Because these stones were formed in layers over millions of years, they have a horizontal grain, and when the stone weathers and breaks, it breaks into large, rectangular blocks. These blocks are perfect for building walls and other similar structures requiring uniformity of stone. The following are examples of sedimentary rock.

Sandstone

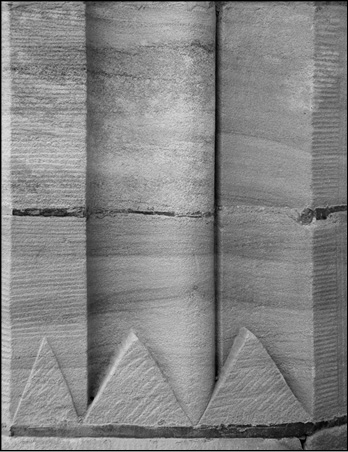

Sandstone is by far the mason’s choice because of how easy it is to use. You can carve it, chip it, or chisel it into whatever shape you need it molded into. Sandstone is unique among sedimentary rock because it naturally takes on a myriad of colors, depending on the location of where it is quarried. Quarrying is the term used to define the actual digging and harvesting of rock and usually takes place in mountainous areas where entire mountains are cut apart using heavy construction machinery designed for moving and lifting heavy loads of rock.

This is a working stone quarry that has belt conveyors and various mining equipment.

Different minerals and oxides in many areas of the country determine the rock’s coloration. In the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, the stone is popular as a building veneer on concrete block because of its vast array of coloration. Veneer is defined as a thin sheet of stone or stones and rock that are cemented to block or, in some early cases, wood. On Prince Edward Island, Canada, there is a type of sandstone naturally brick red in color due to the high concentration of iron oxide in the soil from which the rocks formed. In the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia, sandstone exists that is a dark chocolate color in its natural state, but when it is quarried and weathers, it turns a dull gray color. Most sandstone colors are some form of gray, brown, white, rose, and slate-blue, depending on the region it comes from and the mineral contents of that region. When sandstone weathers, as in fieldstone — naturally occurring chunks of rock found in pasturelands and fields as opposed to quarried stone, which is stone dug from the earth by mechanical means — it becomes softened around the edges, giving it a rounded appearance.

Sandstone commonly breaks in pieces with flat tops and bottoms because as a sedimentary rock, it forms in layers and breaks back in layers when broken or quarried. These naturally worn stones are popular to use when building garden pathways and fireplace hearths because of the lack of sharp edges and abundance of flat surface area. Quarried sandstone exposed to the elements will weather somewhat quickly and achieve the characteristic worn look in a relatively short time, sometimes in just a matter of months, depending on the season or climate. One of the most prized properties of sandstone is that it is porous, meaning the rock is not dense and contains air pockets that collect water and air and help lichen and mosses grow. Ivy will root into the sandstone itself on building walls and thrive quite nicely. For this aesthetically pleasing reason, many gardeners love using the stone in their outdoor landscaping. Most of the quaint British countryside homes have been built with this stone, which allows ivy and moss to grow on its surface, giving it that desired Old World feel. The Smithsonian Museum Arts and Industries Building in Washington, D.C. was built from red sandstone quarried from Seneca, Maryland and is as well known for its trademark ivy-covered walls as it is for the contents of the museum.

The Smithsonian Castle and Information Center was built out of red sandstone quarried from Seneca, Maryland.

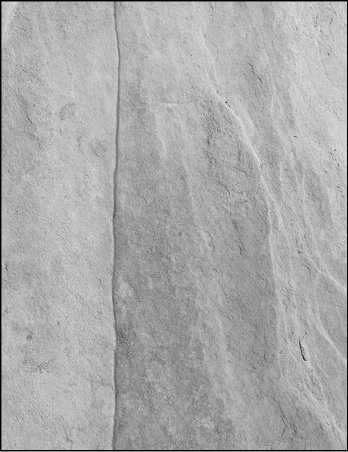

Close-up of sandstone quarried from Fire State Park in Nevada.

Sandstone blocks were used to build this wall at the historic St Francis Xaviers Church, Berrima in New South Wales, Australia.

Close-up of a sandstone rock formation.

This wall was constructed out of different shades of sandstone.

Limestone

Limestone, a denser form of sandstone, was long the material of choice for commercial building in the United States and was even more popular than manufactured brick. Prior to the early 1900s when concrete block became the standard, limestone’s hardness and durability made it used extensively. Brick manufactured in the early 1800s tended to be brittle and broke easily under pressure, while the quarried limestone maintained its integrity and strength.

Limestone is commonly used for carving grave monuments if granite is not used and, therefore, people associate the dark gray color of tombstones with this form of stone. But, some newly quarried limestone has a dull yellow color, although in many parts of the United States, primarily the Appalachian region, it is naturally a dark gray. A limestone found only in northern Kentucky has a light gray color with a blue hint, most likely because of a blue clay indigenous to the region.

Because of how and where limestone forms, imprints of things like leaves and prehistoric seashells are often found dotting the surfaces of the stone. Aged limestone appears almost corroded, although the pitted surfaces, which would seem to indicate weakness, belie the strength underneath. You can also use it in slabs as an attractive flooring material for both indoor and outdoor use, and, with a couple of coats of masonry sealer, it can last for centuries.

Limestone fieldstone is also the stone used most often in dry stonework. Many of these stones are evenly layered and naturally rectangular and brick-like in shape, allowing for easier fits when placed on top of other stone, as in dry stone walls.

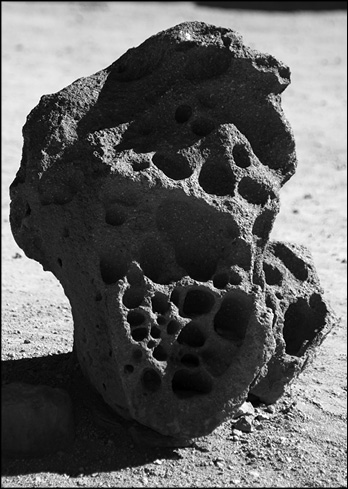

Close-up of Mediterranean coastal limestone.

Close-ups of limestone rock. Photo courtesy of Douglas R. Brown.

Shale and slate

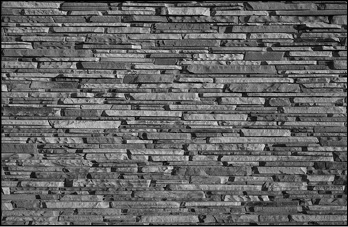

Shale and slate are soft-layered stones used for veneer on more durable manufactured stone, such as concrete block. These stones are not good as primary building stones because they tend to break apart under pressure and do not maintain their strength. Shale and slate are good to use as garden stepping stones and interior floor tiles in areas without high traffic flow. Harder shale and slate stones, quarried below the softer shale and slate and split into layered slabs, are commonly called flagstones. Flagstone is used for flooring on outdoor and indoor patios, high-traffic indoor flooring, and fireplace hearths. Flagstone comes naturally colored in many variations of blue, often referred to as bluestone; brown; red; mauve; and black. Also, a buff-colored flagstone is quarried primarily in New Mexico. Shale and slate is usually dark gray in color to an almost black.

Coquina

Coquina is almost never mentioned as a building stone because of its regional availability, yet coastal states extensively use it. There are structures, such as the famous Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, built entirely from this stone. This fort was built in the late 1600s, and although Florida is known for its harsh tropical climate, the fort still stands today as impenetrable as when the Spaniards used it to defend their holdings in Florida against the British and French. Coquina is mainly composed of the mineral calcite, coral, and phosphate in the form of tightly compacted seashells. It is found along the East Coast of Florida and may be found up to 20 miles inland from the coast in the subsurface, fewer than 4 feet under the earth. People can find coquina rock as far north as North Carolina and also on the South Island of New Zealand where coquina rock formations appear above the surface of the surrounding outcroppings of land along the coast. Several abandoned quarries in New Zealand contain coquina rock as well.

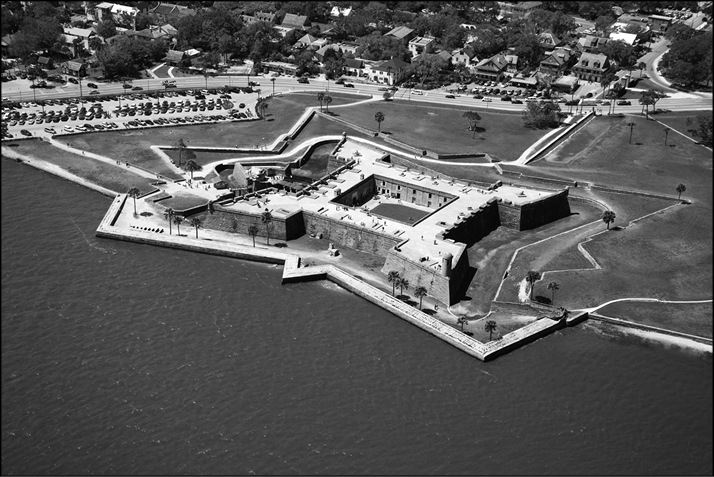

This is an aerial view of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument in St. Augustine, Florida. This fort was built out of coquina rock taken from Anastasia Island between 1672 and 1695.

People have quarried coquina and used it as a building stone in Florida for more than 400 years, and it has provided an exceptional building material for forts, specifically those built during periods of heavy cannon use from invading fleets. Because coquina is a soft rock material, cannon balls would sink into, rather than crush and shatter, fort walls.

When first quarried, coquina is extremely soft and somewhat damp, allowing for easy cutting and shaping. Coquina has to be left out in the weather to dry for approximately one to three years so the stone can harden because it is too soft for immediate use as a building stone. People have also used coquina as a source of paving material but now is only used as filler. They cut coquina into paving stones and laid it flat to make roads for vehicular and carriage traffic, but it was too soft for constant use because it developed breaks and worn ruts over just a few decades. In states where coquina is readily available, such as Florida and Alabama, people add it to asphalt to increase the quantity and to add strength to the mixture. Large rocks of coquina are sometimes used as landscape decoration.

Quarry blocks that are made out of coquina.

Igneous Rock

Igneous rocks form when molten materials cool and solidify, usually below the Earth’s surface. This is known as intrusive rock. The appearance of intrusive rock, such as granite, is mottled with large crystallizations of mica and glass. A slower cooling-down period inside the earth causes the large crystallizations. Alternately, some igneous rock forms above the surface when lava cools and hardens, creating new land surface. This is called extrusive rock. Solid volcanic lava, greenstone, and basalt are examples of extrusive rock, and crystallizations are much smaller. In some rocks, such as obsidian, you cannot detect them with the naked eye. Obsidian is as close to a naturally created glass as it gets in the rock world.

Igneous rocks are very hard and are used where texture and permanence are desired, such as in buildings and stone gate pillars. But, these are difficult to shape for building, especially by hand. Some basalt is so glass-like in structure it will actually slice skin. Beginning stonemasons should not use this form of rock in their projects.

Example of igneous rock found near a small village in the Atacama Desert. There is a volcanic plateau in Chile, South America west of the Andes Mountains that created this.

Close-up, detailed picture of igneous rock.

Granite

Granite is a coarse-grained, igneous rock, which makes it much harder and denser than sedimentary rock. It is difficult to work with because of its density. Recently, people started to associate granite with its use as countertops and flooring in modern homes, but in the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was used for impressive public buildings, such as museums, courthouses, and hospitals. Granite’s natural strength and durability make this stone harder to work with because it has a variable texture that tends to break into less-desired shapes. To cut granite, a stonemason must use an air-powered cutting tool, and the dust generated from this procedure can be very hard on the lungs. With the advent of more complex machinery, such as massive pneumatic and hydraulic drills, you can now achieve precision cuts and thinner blocks of this stone without as much dust or accidental breakage.

The most common color for granite is a dark, speckled gray, but because of its high content of feldspar and quartz, natural minerals that affect the coloration of stone, it also takes on dark blue, greenish, and pink tones, both individually and within the same vein of rock. When granite breaks because of climactic changes or forces of nature, it breaks into huge stones weighing more than 500 pounds and up to a ton; therefore, most granite is now commercially quarried. Early pioneers and settlers have already picked up the smaller, more accessible fieldstone granite, smaller chunks of granite quarried commercially or naturally, and used it in building structures, such as springhouses — where dairy products and eggs were stored to remain cool — and root cellars — where many farmers kept their root crops and seeds for the following planting season. Many of the granite stones used in old foundations, chimneys, and basements are now recycled when the original structures are torn down or rebuilt. As long as you can move the stones, you can reuse the stones.

Kitchen that has granite countertops and back splashes.

Basalt

Basalt is another commonly used stone classified as an extrusive stone and has the same properties of granite but without the grain. Basalt is much like obsidian in that it forms from rapidly cooled volcanic eruptions. Because of the rapid cooling process, basalt does not form interior strata but instead has a glass-like structure. It is an igneous rock and is very difficult to work with because it is so hard and is not easy to carve. But, it does possess an admirable density, with very little, if any porosity, and has a rich, black color. It is associated with many Japanese Zen gardens where large, carved basalt is often used as a meditation point. Crushed basalt is used as an aggregate in asphalt and is used by railways as ballast. Ballast is any heavy material, such as rock and stone, used to stabilize a ship. It is also used as coarse gravel laid to form a bed for streets and railroads. Basalt also forms most of the underlayment of the Earth’s surface.

Close-up of the texture of basalt.

Turret of an ancient fortress in Pico Island, Azores. The turret was built out of basalt.

Rock gate at the cliffs formed by volcanic basalt columns in Arnarstapi, Snaefellsnes Peninsula, Iceland.

Basalt rocks are commonly used in hot rock treatments.

Greenstone

Greenstone is a type of basalt found in regions of the southeast United States, particularly the Blue Ridge Mountains. It merits mentioning because of its unique properties, not only in building but also because it adds the element of sound. When struck, most stones emit a dull noise. But, because it was formerly prehistoric sea lava and it contains a high concentration of metallic oxides, greenstone possesses the unique ability to emit a ringing sound, like a bell, when struck. It forms in long, greenish-blue shards and is very hard to carve or cut. It tends to break in thin shanks and can only be used as it is found. Being an igneous rock, it is very hard and durable, which makes it desirable, particularly for accent or veneer over concrete block or brick. Quarries usually blast out the stone and use it as landscaping accent, such as a rock placed in the middle of a sitting garden or as the base for a fountain or birdbath. It is also used for making riprap, which is irregular stone used for fill or to hold against erosion. People have made fireplaces and other indoor accents completely with greenstone found in fields, but it is a difficult stone to work with because it is so difficult to carve or cut.

Geographic Locations of Natural Stone throughout the United States

Although you can find many types of stone, particularly sandstone and limestone, in almost all of the United States, there are certain areas where particular types of rock are more prevalent. It is always advised to use a native stone in your work, primarily because it fits the look of the landscape. It is odd to see a startling piece of black granite in the middle of a cactus garden in Arizona, for example, but a carved piece of sandstone would perfectly accent the surrounding garden materials.

Certain regions of the United States are rich in natural rock, particularly those with mountain ranges. In most of Kentucky, dry stone rock walls and stone-built homes are reminders of the state’s pioneer past and are considered national treasures. You can find stone by walking your property and digging up usable stone, or you can visit local quarries or stone yards. You can find out if your city or town has a stone yard by checking the phone book or by searching the Internet for the closest stone yard in your area. It is more beneficial to purchase stone from a stone yard simply because you can choose your stones for their already formed shapes, colors, and sizes, and you can have them delivered, which is advantageous if you do not own a truck or have access to one. But, if you are building a rock or water garden and have usable stone on your property, it is perfectly acceptable to use native rock because it blends with the surrounding landscape.

A caution exists in using fieldstone: You cannot remove native rock from state parks or preserves without a National Forest Service permit or Department of the Interior permit, and you certainly cannot use rock found on other people’s property without their consent. Some builders and contractors welcome the removal of stone from specific building sites, but you still need to get permission from the landowner before removal.

In order to obtain a permit for gathering rock, which is considered a forest product, you need to contact your local state office for the National Forest Service. The website for information is www.blm.gov, or you can call the toll-free number for the U.S. National Forest Service at 1-800-832-1355. You can access individual state offices by going to their website at www.blm.gov/wo/st/en.html, calling 202-208-3801, or writing the main office at:

Bureau of Land Management

Washington Office

1849 C St. NW, Rm. 5665

Washington D.C., 20240

More About Fieldstone

Fieldstone is defined as just that: Stone that occurs naturally in fields and is used as building material. Gathering fieldstone can be a laborious process that entails many trips back and forth from creek banks and mountainous areas. The National Forest Service imposed a fee for stone collecting, which allows you to gather a specific quantity of stone over a certain time from national forests and for personal use only. They impose a fine for not getting permission to collect stone and rock from public lands. Gathering from streams, using heavy machinery, and gathering for commercial use and resale is prohibited. What is not prohibited is collecting rock and stone from mountains and hillsides, along riverbeds but not in the stream itself, and pasturelands. Backhoes and bulldozers, commonly used to quarry rock, destroy public lands, which is why they are not permitted.

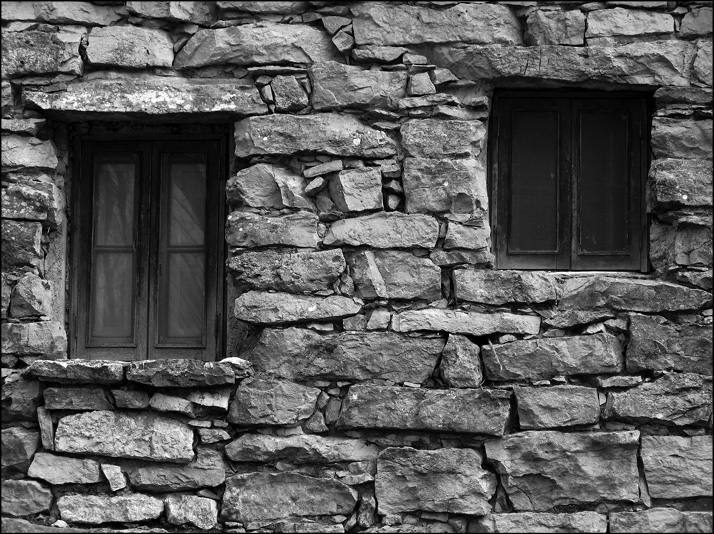

Fieldstone is used like any other stone because dry stacking, which refers to stacking dry rock on top of each other in such a way the stones interlock and stand firm without the use of mortar, can hold fieldstone in place. Fieldstone is commonly used in building outdoor walls and fences; structures, such as springhouses, grottoes, or residential homes; and oftentimes fireplaces. Using fieldstone is trickier than using quarried stone because the surfaces are not cut, and they require shaping. But, the weathered look of the stone provides one of the reasons people prefer using rocks they find in nature as opposed to ones they purchase from a quarry. Other benefits to using fieldstone include that it has already aged to the color it will be when used; it has softer, rounded edges; and best of all, it is usually free, or cheaper, than purchasing quarried stone.

This stone wall was made using dry stacking techniques.

You should choose fieldstone close to the shape you will need so you have minimal work to do to the stone once you move it. Limestone and sandstone both occur in layers, and finding a few loose stones usually means there will be plenty more nearby. You can easily load the bed of a truck with stones, and after a few trips, you may have enough for your project with minimal or no financial cost.

When gathering fieldstone, always remember to exercise proper caution. Never climb up or down wet slopes, never try to lift overly heavy stones, and take your time when gathering stones to avoid straining your muscles and to not put yourself or others in danger by rushing about. Your backyard barbecue pit project is certainly not worth broken bones. It is also good safety practice to travel with someone else in case a problem occurs and to help you gather and lift stones.

Roadsides near farming communities also contain fieldstone. Farmers often plow their fields and remove the resulting rock and stone by throwing them over a fence and away from their crops. You can gather fieldstone from alongside creek beds but not from within the streams, as it is illegal in all states. Although the rocks in streams are tempting to remove because they are large and rounded by the constant washing of water, you cannot use them in your projects. Whenever a landowner prepares property for building a home, you can usually ask the landowner for permission to load up some, or all, of the upturned rock.

Example of a house that was made out of fieldstone.

Good sources of recycled stone include abandoned or burnt brick or stone homes and chimneys. You can use these stones or brick in conjunction with other fieldstone. Many old chimneys and structures built before 1900 and the advent of Portland cement used a form of mortar called lime-and-sand mortar, made from dry lime and sand and then wet with water to make a loose, adhesive grout. This grout, over the course of a few years, became quite brittle, and the lime helped corrode the soft brick. Most of this lime-and-sand mortar is easily dug out away from the stone so you can easily reuse the stone itself. Again, always get permission from landowners before gathering. Do not assume the landowner will not care because the stones have been on vacant property for years. It could be a National Historic Register structure, which carries a huge fine to the hapless stone gatherer if meddled with.

Tips for gathering fieldstone

Although you may think gathering fieldstone simply requires picking up a few rocks and tossing them into the back of your truck, certain things can maximize how efficiently you gather stone, preventing unnecessary trips and saving time.

1. Choose stone by shape

When gathering stone, look for flat surfaces and square or rectangular shapes. These stones will form the corners, overlapping the other stones on two sides and providing a flat base for additional stones. These stones will also serve as arch stones, which are stones that form an arch, if you are including one in your building construction. These kinds of stone lay easier and require little cutting. Ideally, fieldstones are used without mortar, and they should fit as evenly and tightly together as possible. This does not mean you should always disregard a stone because it is not perfectly flat or square. Many dry stone fences and walls are made with beautiful, flat stones set in a vertical or horizontal fashion as capstones, defined as stones that finish off the top of a wall.

2. Gather more than you need

This is a standard rule of thumb for stone gatherers: More is better. You never know if you will need more or less, and it is always better to have excess stone so you will not have to stop in the middle of your project and go in search of more or wait for a delivery from the local stone yard. Whereas carpenters have a “measure twice, cut once” rule, stone gatherers have a “50 percent overage” rule, meaning you should always gather 50 percent more rock that you think you may need to complete your project. You can always use this rock later in another project. If you have a stone yard in your town, you may possibly sell your overage to them, and they will load it and carry it off for you. As long as you gathered the rock for personal use initially, if you have an overage, then you can dispose of it in any fashion you see fit.

3. Be kind to the Earth

When you dig out stones from public or private lands, fill in or cover the areas where you dug with leaves and brush to keep the area from washing out in heavy rains. Be respectful of the property of others if you gather on their land, and always try to fill in the spaces where you dig with earth and brush, leaving the scenery intact and just as beautiful as you found it. Remember: You must always have permission to dig on any public or private land.

Quarried Stone

Quarried stone is stone mechanically extracted from the earth rather than exposed due to natural erosion or the preparation of building sites. It is stronger than fieldstone because the surface of the rock has not been exposed to weather for a long time. As stone naturally ages, minute cracks allow water to seep into the rock’s interior, which freezes, and eventually these small cracks enlarge and lengthen. The stone will then break into smaller stones and, over thousands of years, it eventually becomes sand or grit. With quarried stone, this natural process has not happened, and the rock is harder and denser than fieldstone. There is also a caveat to quarried stone: In most cases, the quarried stone has at least one flat side or more. This is essential when building structures to ensure a level and even surface.

Most quarried stone is sold through stone yards, which can be a blessing or a curse. If you are looking to build a dry stone structure, you are rarely allowed to pick and choose the stones you want because they are sold on a pallet with plastic wrap to keep the rocks and stones intact, and these pallets do not always include the best stones for the type of project you are working on. Most stone yards cater to masons who use mortar for building their projects. You can certainly mix commercially quarried stone with fieldstone to make your purchases more cost effective.

Faux stone

The Southwestern Native Americans are credited with the first fabrication of faux stone, which was native soil and clay formed into small bricks. They used discarded vegetable matter, such as corn shocks and wheat chafe, to strengthen these bricks, which is commonly referred to as adobe. Because adobe bricks are man made, they are considered the first faux stone. In modern times, the availability and diversity of faux stone has come a long way. Commercially made faux stone began with a product called Z-BRICK®, one of the earliest manufactured stones. Now, many faux stones exists, mimicking every natural stone and texture with every color imaginable. Even entire faux stone panels exist, making it even easier to install a stone-looking wall in your home.

The Zygrove Corporation, the manufacturers of Z-BRICK, was the first company to manufacture and market this type of product to the public for use inside and outside the home. Originally, making your den or kitchen look like it had brick walls provided the most popular use for Z-BRICK. Z-BRICK now manufactures more natural-looking veneers and has a veneer stone specifically for outdoor walls in exterior foyers and patios. It has been one of the best selling products for this purpose since its introduction in 1955 and continues to be in demand today. One of the components of Z-BRICK is vermiculite — a natural mineral formed with a high concentration of clay, which expands with heat. Vermiculite is used in commercial and residential insulation and is used to add air pockets to garden soil. It also makes Z-BRICK stone and brick lightweight and natural in texture. According to the website for Z-BRICK (www.z-brick.com), the main difference between a Z-BRICK and an all clay-based brick is Z-BRICKs are lightweight, dense, and thin instead of brittle like natural clay brick, and they are more cost efficient than masonry brick.

Currently, hundreds of companies manufacture faux stone and faux stone panels with lifelike replicated textures. You can order panels that slide open, faux rocks for waterfalls and other outdoor uses, and even replicated stone, which is the new terminology for faux stone, in bendable sheets for encircling round objects. Manufactured stone panels can vary greatly in price from one dealer to another, and you must remember the golden rule of retail: You get what you pay for. Replicated, or faux, stone can be just as visually appealing as natural stone, but many of the cheaper products do not have the intricate colorations that natural rock offers. Therefore, if you are considering using faux stone in any veneer work, then weigh your options carefully and choose a stone that will give you the accent you are looking for at a reasonable cost, but do not always go for the cheapest option if you can afford it. In the long run, it is always better to spend the money on a higher quality of faux stone because it will reward you with many years of durability and good looks. This book will focus on using natural stone, rather than faux stone in various projects. But, Chapter 6 dedicates information on how to use faux stone as a veneer on concrete block.

Now that you know what types of stones are available to you, Chapter 2 will help you figure out what tools are necessary and what their uses are so you can officially begin your education in working with stone.