We are the creatures of the institutions we have made, and this is no less so because we have made them. There is a helix of interaction between man and his works so that the effects on him of his works spur him to further works which have further effects, and so on until it is impossible to tell which is man qua man and which is his work.

J. F. FEIBLEMAN (1956, 80)

The general consensus that the inception of civilisation marked a major advance for man, ‘the turning point in the changes which mankind has undergone’ (Redfield 1953, ix) implies inescapably that the early civilisations in different parts of the world had certain things in common, that their development was in each case a particular instance of some more general process, the transformation from ‘primitive’ to ‘civilised’. Any understanding of the emergence of one of the world’s early civilisations which we may reach would therefore throw some light on the early origins of them all.

There is little agreement among anthropologists as to just what it was that these early societies did actually hold in common to distinguish each as a civilisation, and still less agreement about how this great transformation came about. The first step, then, must be to indicate what it is that we are trying to explain: to say what is meant here by civilisation, and how a civilisation may be recognised. Clearly there will be almost as many definitions of civilisation as there are archaeologists making them. But it is important to justify the use of this term to indicate human societies of a particular kind, and to demonstrate its applicability to the Minoan and Mycenaean communities of the early Aegean. Such is the task of this first preliminary chapter.

‘Civilisation, like culture’, has a colloquial meaning. A man is ‘civilised’ if he behaves decently and ethically. ‘Savagery’ is frequently equated with brutality, and enemies are described as ‘barbarian’. This is, of course, not simply anthropocentric but egocentric—like the arrogant lumping together of the art forms of all non-civilised communities as ‘primitive’.

In this sense, it is perfectly logical that the Aztecs, for instance, should be regarded as uncivilised in view of their practice of human sacrifice. Equally we might so qualify the Greeks because they exposed unwanted babies to die. But these are value judgements, and ‘civilised’ in this sense can only mean conforming to our own standards of morality and conduct. For the anthropologist the definition is too subjective to be useful.

The archaeologist makes a valuable distinction between culture, a general attribute of man, and cultures, each a specific adaptation of a human group to the particular problems of its environment. Culture, in the generalised sense, has been well defined (White 1959, 8) as ‘man’s extra-somatic means of adaptation’. More than anything else it distinguishes man from other animals, being learnt and not inherited as part of one’s genetic composition. A culture on the other hand (and note the indefinite article), designates a specific human adaptation at a given time and place. The archaeologist gives the term a special meaning (Childe 1929, vi): ‘a consistently recurring assemblage of artefacts’. This definition is particularly convenient, couched as it is in operational terms relating to what the archaeologist actually finds. It assumes that the different specific adaptations may be recognised and distinguished by means of the different artefacts which the members of the group habitually used.

Just as a distinction can be made between culture and cultures, the latter being localised in time and space, so we can distinguish between civilisation and civilisations. Civilisation is a stage, level or state of cultural development, and the main purpose of this chapter is to characterise it more clearly. Anticipating that definition for a moment, and assuming that it can be formulated, we can be specific about civilisations. A civilisation (and the indefinite article implies the possibility of specifying its geographical and chronological position) is a culture of a particular kind. A civilisation is then, in the operational language of the archaeologist, ‘a constantly recurring assemblage of artefacts’—of a particular kind. Underlying the operational definition, again, is the notion of a group of people sharing a unique way of life, a unique adaptation.

The craft specialisation and social stratification which we shall find to be features of all civilisations imply that, strictly speaking, there is no single recurrent assemblage, but several interrelated assemblages of artefacts (as indeed is often the case for cultures in general). But otherwise a civilisation resembles a culture in requiring spatial and temporal definition. The Sumerian civilisation, for instance, is defined by the distribution of artefact assemblages predominantly and specifically of Sumerian type. And the definition can be extended to cope with traded products, or with discontinuities, like that documented by the Assyrian trading colony at Kültepe, many miles from the continuous distributions of the Mesopotamian homeland.

It is more difficult to specify the temporal boundaries than the geographical ones the decision is an arbitrary one, although in rare cases the end may be sudden. But no new civilisation ever had a sudden beginning or ‘birth’.

Any distinguishable culture whose institutions and material achievements fulfil the defining criteria which we choose to adopt is properly termed a civilisation. We can thus speak of the Sumerian civilisation, the Indus civilisation, the Maya civilisation and so forth. But always the precise definition employed is based upon criteria which are essentially arbitrary: the Minoan civilisation and the Mycenaean civilisation can be redefined so as jointly to constitute the Minoan-Mycenaean civilisation; the Olmec, Maya and Aztec civilisations can be lumped together as Mesoamerican; in the same way the classical world can be divided into ‘Greece’ (until the second or first century BC) and then ‘Rome’. It remains to decide what distinguishes this state or form of culture known as civilisation from other states or lands of culture. Various criteria have at times been put forward, and some of these will now be considered.

In his book Man Makes Himself, Gordon Childe elaborated his notion of an ‘urban revolution’ by which civilisation was created in the Near East: this was a pioneering attempt to explain the process in detail. For Childe, a key feature was the formation of the city, the beginning of urban life—as indeed it has been for most thinkers and historians from the time of Sophocles to the present. ‘In the Near East the Bronze Age is characterised by populous cities wherein secondary industries arid foreign trade are conducted on a considerable scale. A regular army of craftsmen, merchants, transport workers, and also officials, clerks, soldiers and priests is supported by the surplus foodstuffs produced by cultivators, herdsmen and hunters. The cities are incomparably larger and more populous than neolithic villages. A second revolution has occurred, and once more it has resulted in a multiplication of our species’ (Childe 1936a, 37).

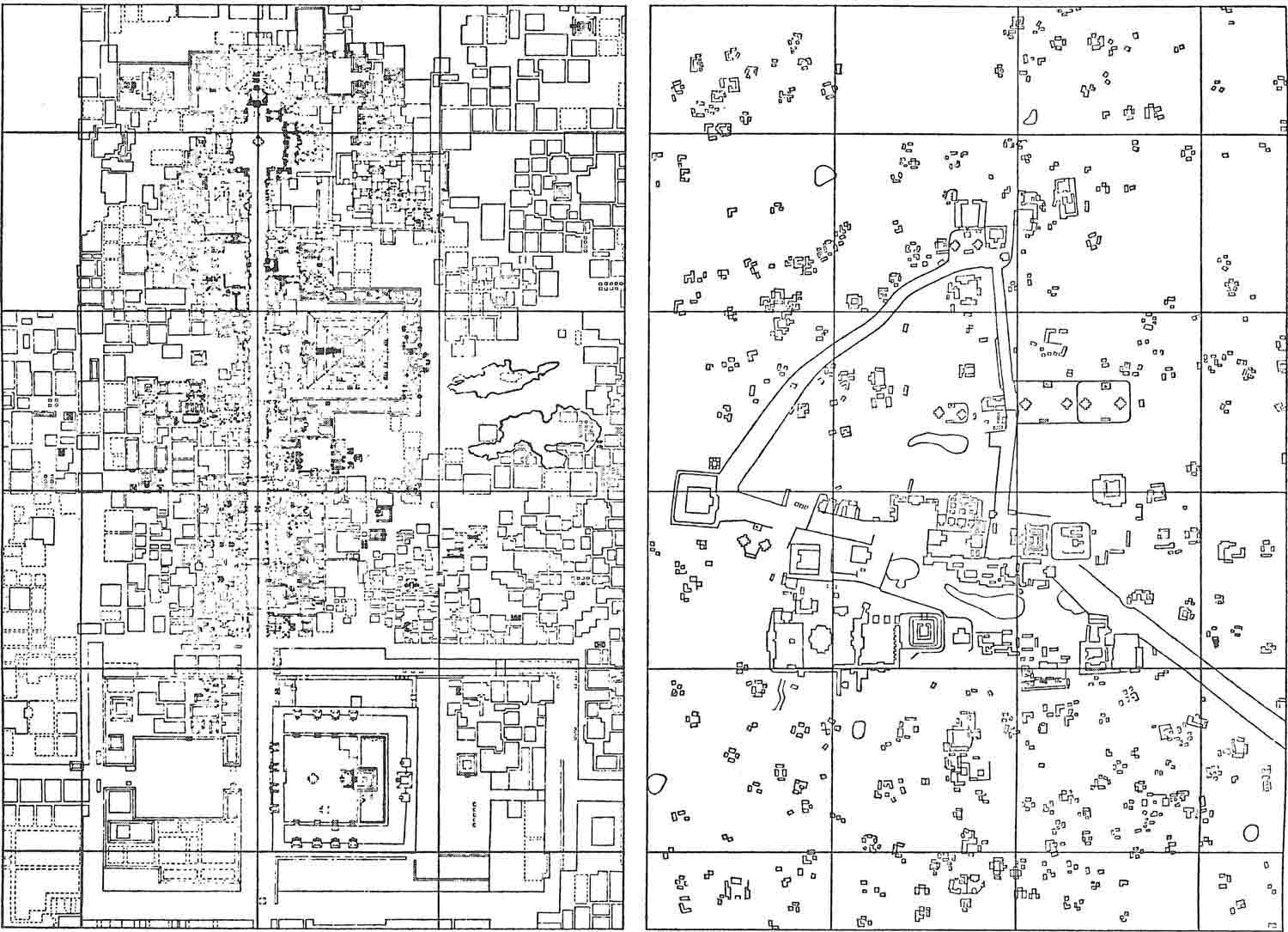

For Lewis Mumford too, the essential feature of civilisation is the city, the ‘container’ as he graphically terms it, for all the new activities of civilised life. For him the urban revolution was ‘the implosion of many diverse and conflicting forces in a new kind of container, the nucleated city’. ‘The city is the means of transforming power and productivity into culture and translating culture itself into detachable symbolic forms that can be stored and transmitted’ (Mumford 1960, 338). Yet there is no one-to-one correspondence between civilisation and cities. Several authors have emphasised (Coe 1962, 66) ‘that: there is now excellent evidence that many early cultures which possessed all the other criteria of civilisation seem to have been non-urban. Among them are the Maya, Khmer, Mycenaean and pre-eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian civilisations’. The great temples of the Maya, the elaborate calendar, and the monumental sculpture, which testify to an elaborate religion and very developed technology, were not accompanied by a particularly high population density or by recognisable urban units. It would seem difficult to deny to Tikal, the great Mayan ceremonial centre, the appellation ‘civilised’, or indeed to Angkor Wat. Yet Tikal contrasts markedly with the huge early city of Teotihuacan, likewise in Mexico. The central area alone of Teotihuacan exceeded in size the entire agglomeration of buildings at Tikal, and Teotihuacan unlike Tikal was the seat of a very large population (see fig. 1.1).

Although the densely populated city is the most obvious symptom of civilisation, it is not an essential component. On the other hand, probably no civilisation lacks the monumental public buildings—whether granaries, palaces or temples—which seem indeed to be present in every community which one would wish to term civilised.

The presence of writing is another key feature, whose importance has frequently been underlined (cf. Gelb 1960). But several cultures upon which it seems appropriate to bestow the term civilised, such as that of the Incas of Peru, had no effective form of writing. And indeed the glyphs of the Olmecs and Mayas seem to have been employed principally for calendrical notations.

FIG 1.1 The contrasting density of settlement at Teotihuacan (left) and Tikal (right) in Mesoamerica. Tikal is the largest of the lowland Maya ceremonial centres, yet scarcely ranks as a city in terms of population or density of settlement. Both sites are shown at the same scale (squares of side 500 m) (after Millon).

The central significance of a state religion has often been stressed, but this again is hardly a satisfactory universal criterion. No temples are yet known in the Indus civilisation for instance, and the little shrines of Crete and Mycenae are not greatly impressive. On the other hand, the massive monumental temples of Malta belonged to a culture which had few other advanced features.

Social organisation and craft specialisation are features emphasised by nearly all historians of early culture. As Robert Adams has written (1966, 12): ‘I also believe that the available evidence supports the conclusion that the transformation at the core of the Urban Revolution lay in the realm of social organisation; ... in the case of complex state societies, their rise is accompanied by the progressive dissociation of major institutional spheres from one another.’ It does indeed seem that all civilised societies have a well-defined social organisation, where craft specialisation is generally also seen. But it Is, on the other hand, not easy to formulate universal criteria by which these features may be recognised from the archaeological record.

It appears then that no single feature or symptom of civilisation, which can be singled out and sought for in the archaeological record, can be used as the overriding and defining criterion.

Indeed, when seeking an operational, working definition, it seems preferable to take a polythetic criterion—that is to say one that is based on the presence of a certain number, but not necessarily of all, of a series of defining features. Gordon Childe listed ten such features which distinguish the earliest cities from villages (Childe 1950b), yet it was Clyde Kluckhohn (1960, 400) who first formulated a definition in explicitly polythetic terms:

‘City dweller’ and ‘urban’ loosely designate societies characterised by at least two of the following features:

(i) towns of upward of, say, 5,000 inhabitants

(ii) a written language

(iii) monumental ceremonial centres.

If we are to formulate such an operational definition, with criteria which are inevitably somewhat arbitrary, this seems a very acceptable one. It embraces all those early cultures which are usually designated civilisations. And it excludes societies with only a single astonishing feature, like Stonehenge, or the temples of Malta, or indeed the Tărtăria tablets of Romania.

One would wish to go further, however, and seek a statement of something more central to the idea of civilisation than a mere choice of its symptoms. As Adams has observed (1960, 291): ‘In addition it is of course implicit in this discussion that the common social institutions and processes of development identified in each of the four civilisations were bound up together with this general constellation of subsistence practices in a functionally interacting network which characterises early civilisations as a sort of culture type.’

Henri Frankfort likewise felt the need to grasp at a single, more central idea, and wished to define: ‘the individuality of a civilisation, its recognisable character, its identity which is maintained through the successive stages of its existence.... We recognise in it a certain coherence among its various manifestations, a certain consistency in its orientation, a certain cultural “style” which shapes its political and its judicial institutions as well as its morals. I propose to call this elusive identity of civilisation its “form”. It is the form which is never destroyed, although it changes in course of time’ (Frankfort 1951, 16).

The use of a term such as ‘form’, itself not adequately defined, can never be very meaningful. Yet Kluckhohn’s general definition, while capable of objective and rigorous application, is hardly a satisfying one either. Surely, one feels, there must be some central, core idea, some unifying concept to make our definition of civilisation something more than a polythetic bundle of apparently ill-assorted culture traits.

In the next section such a concept is outlined. As a definition it is certainly not as rigorous as Kluckhohn’s, which remains perhaps the most convenient for practical, operational use. Yet it does, I would claim, give a more satisfactory general statement of what we mean by civilisation, and of what different civilisations hold in common. For this reason it may be more useful when we are considering the origin of the Minoan/ Mycenaean civilisation.

Many of man’s activities are conditioned by his cultural environment, and satisfied by certain interrelations with it. The term ‘environment’ here is not intended as a metaphor: when man comes into the world he rapidly comes into contact with things, people and ideas outside himself. If a man lives among people, these are part of his environment as much as the local geology, or plant life, or the weather. If he lives in a house, this is part of his environment. If he is taught a religion, this too is part of his environment, since his behaviour and activities are conditioned by the forces which he believes act upon him rather than by those which the sceptic may recognise.

To some extent these different aspects of the environment may be regarded as independent. A man’s social actions do not necessarily impinge directly on his quest for food, nor his religious beliefs and activities on the interior design of his home. Ultimately, as the functionalists would hold, there may be a relationship, but these different fields of activity can be distinguished. In this sense man’s environment is multidimensional and, consequently, his culture—his adaptation to his environment—is multi-dimensional too. As Lewis Binford has put it, ‘Archaeologists ... are measuring along several dimensions simultaneously, ... culture is neither simple nor additive’ (Binford 1968a, 24).

To say that culture is multi-dimensional does not of course mean that the dimensions are precisely analogous to the three spatial and one temporal dimension with which we describe space-time, and the definition of these dimensions will always perhaps be an arbitrary one—a situation which will not dismay the mathematician who is used to transforming his variables or rotating his sets of variables.

The environment to which a man is born is not static—it is dependent on the religion and social beliefs and customs, the technology, mores and language of his society, that is to say on its culture, as well as on nature. And this environment is itself largely the product of human actions, over a long period of time, themselves shaped by the heritage of customs and tradition of the society. It is, indeed, an artefact—or rather a complex amalgam of many artefacts, as well as of natural objects and processes. Language, of course, is an artefact, although not a material one, and not the product of a single craftsman. But its form is uniquely determined by human action and convention just as much as that of a Sumerian temple or a British teapot. Religion (seen from the standpoint of an anthropologist rather than of a believer) is an artefact in the same way, as are all explicit theories about the world. Once again, this is not a metaphor—these things are made by man.

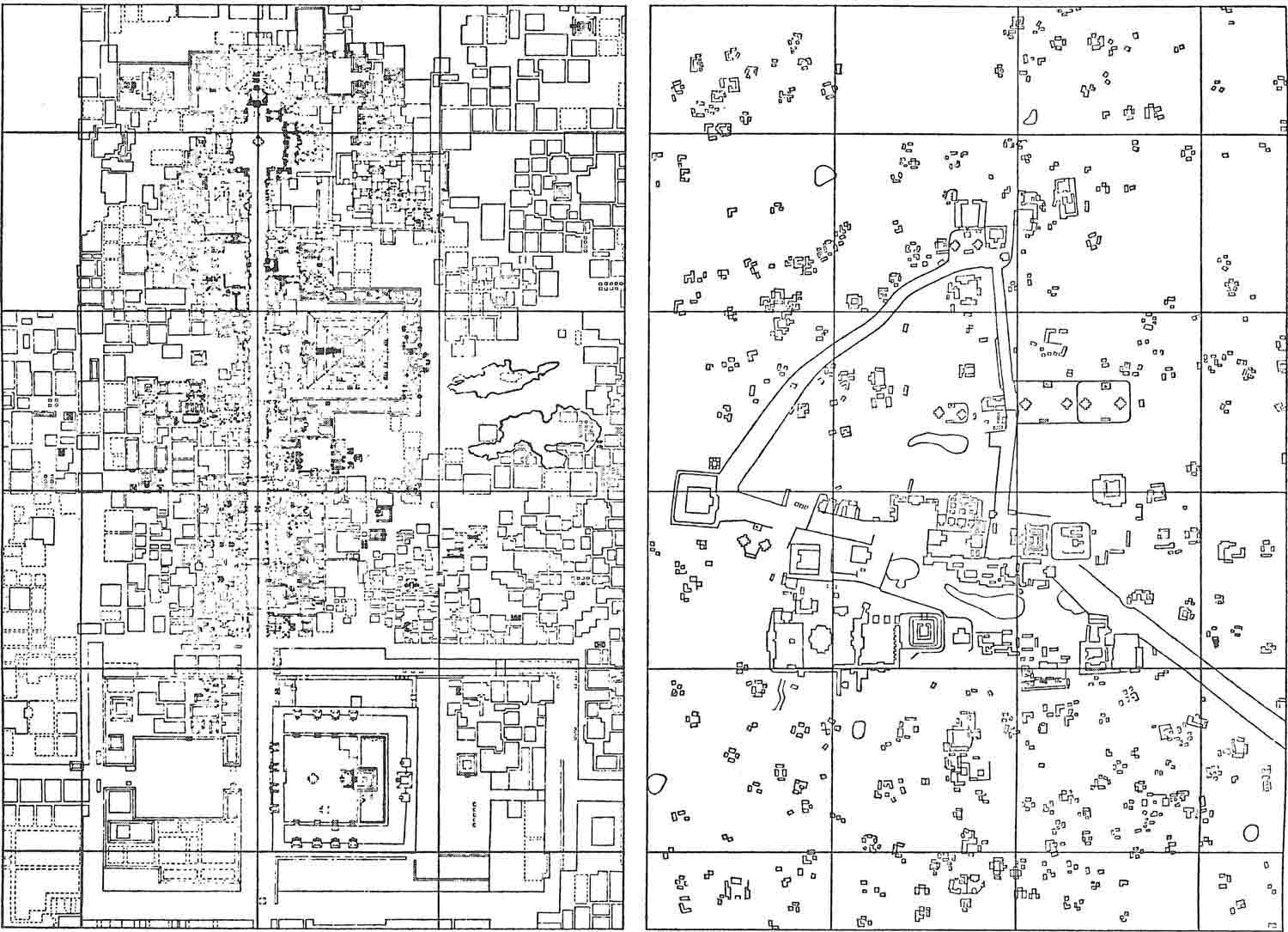

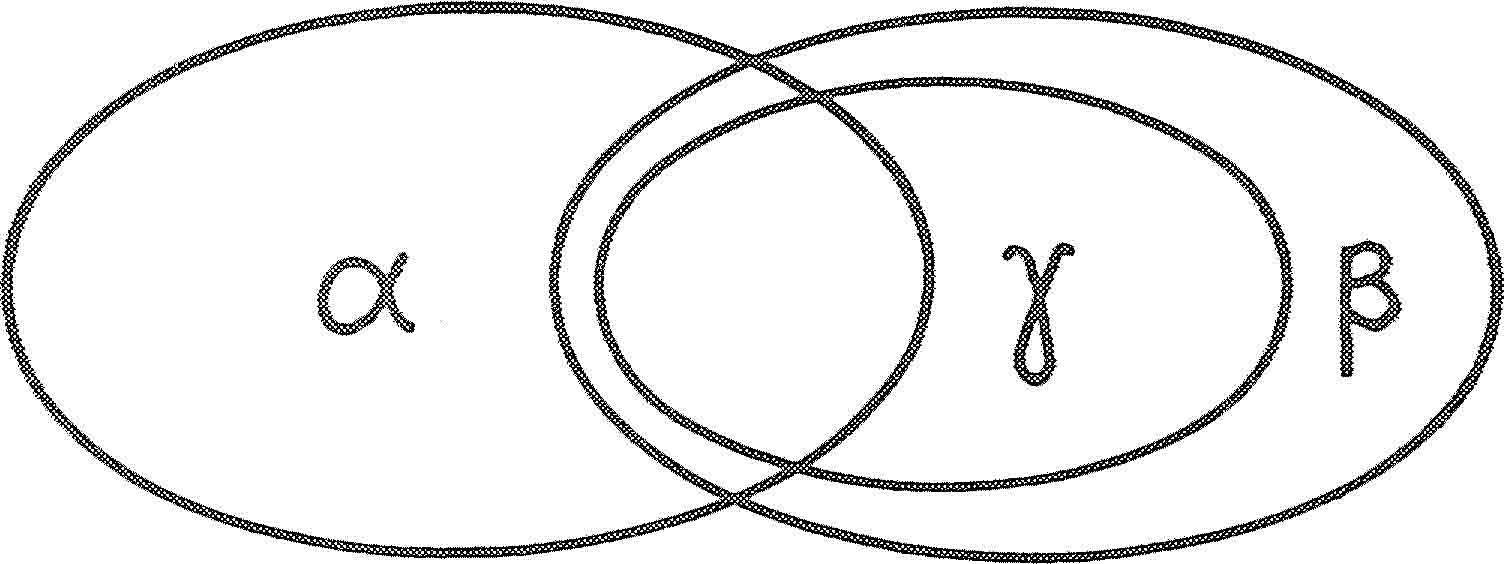

FIG 1.2 The activities of man (β) when he is viewed simply as one component of the ecosystem (α).

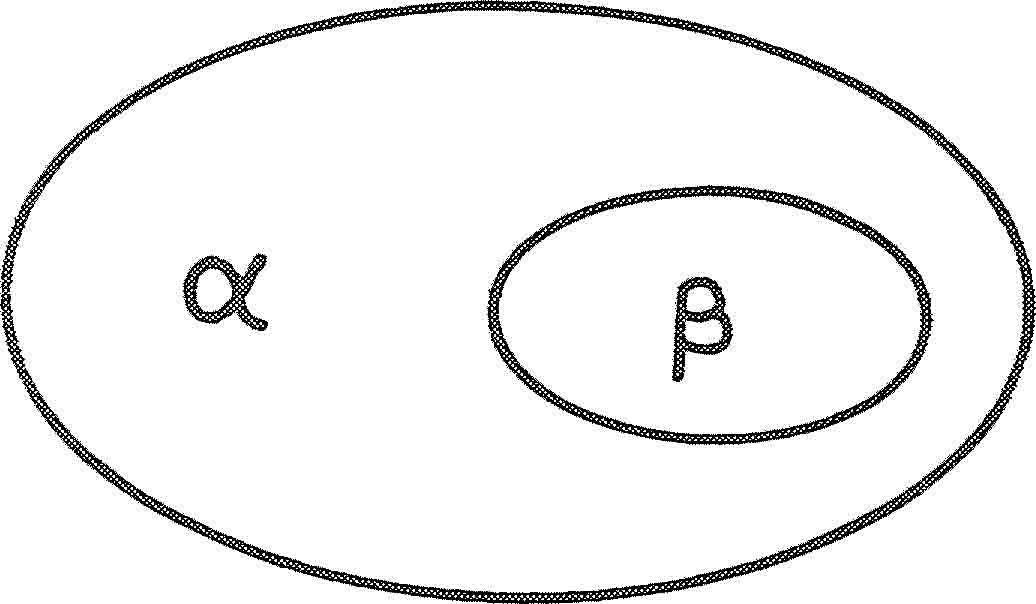

FIG 1.3 An anthropocentric view of the activities of a man (β). Some of his activities interact directly with the ecosystem, and are still activities of the ecosystem (α). The activities of other men are represented by the field γ, and the overlap between β and γ represents the field of this man’s social activity.

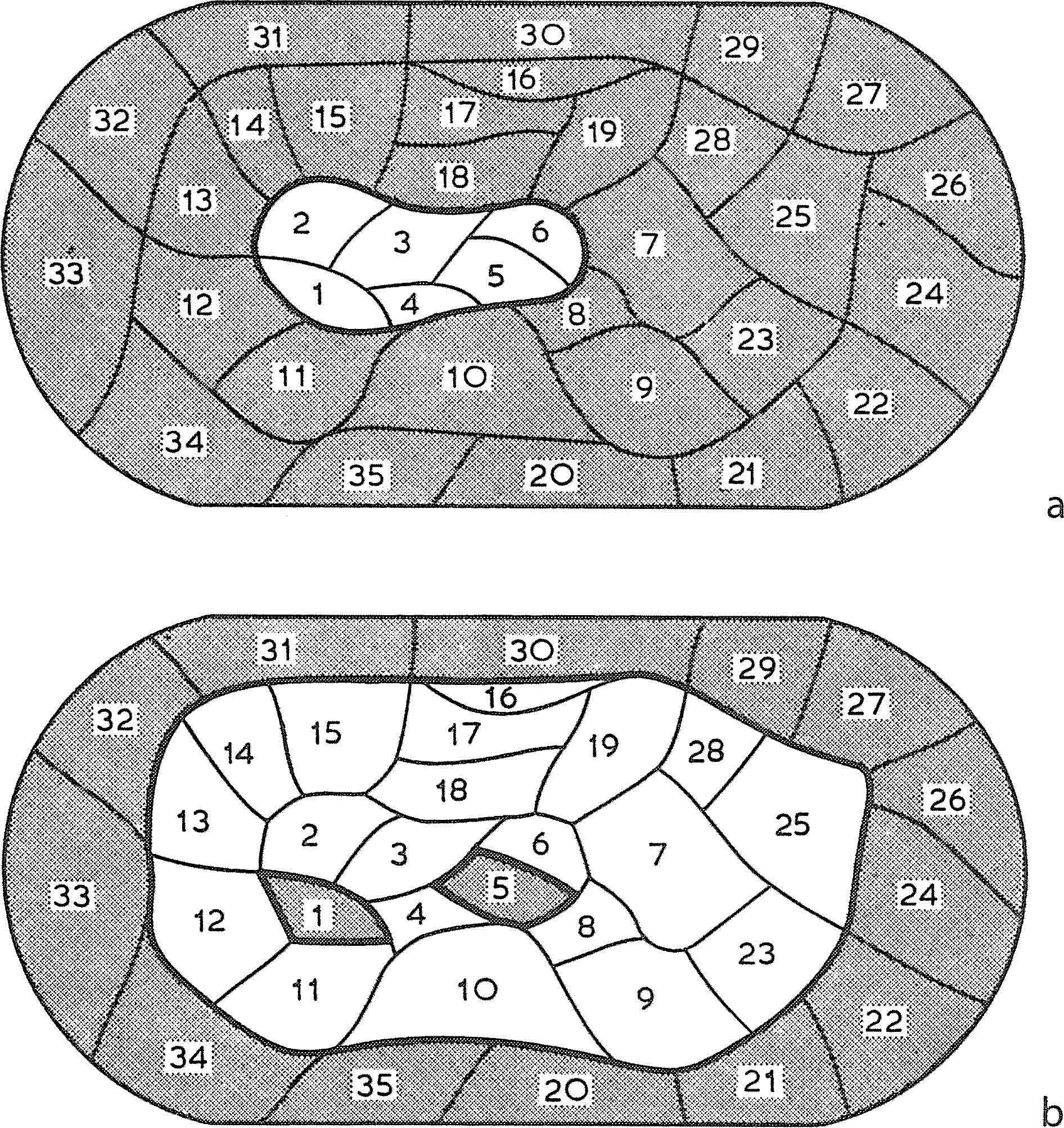

Imitating the topological psychologists, we can compare the developing environment of a culture with the changing environment of life-space of a child. Fig. 1.4 from Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory in Social Science (1952, 136), illustrates graphically how certain ‘areas’ of existence are open to a child, others to an adult: the ‘life-space’ is different. Geographers today, in the same way, use the concept of perceptual space. We can apply this image directly to man’s environment. Let the unshaded area in fig. 1.4, a be the natural world accessible to an Upper Palaeolithic hunter. And let the unshaded area in fig. 1.4, b be the natural world accessible to an Early Dynastic Sumerian. Nos. 2, 3, 4 and 6 represent the areas accessible to both (wild plant and animal resources, flint for chipped stone etc.). Areas 7 to 23 designate fields of activity always potentially open to the hunter, such as cereal plants, copper and resources overseas. But these elements of the world only become effectively part of man’s environment after the domestication (or at least intensive exploitation) of the plants and animals, the discovery of the smelting of copper ore and the construction of boats. Man’s environment has then been greatly enlarged, and the increase has been the result of cultural acquisitions, of the production of what are in the broader sense new artefacts. Boats, for example, are artefacts, as is smelted copper and, indeed, the technical skills required for its smelting. In a meaningful sense, so too are domestic plants and animals, since the most satisfactory criterion of domestication is controlled breeding. An artefact can, in the same way, be the work of many generations, and can be formed without any prior and deliberate plan, the accretion of the efforts of many different periods. Many medieval cathedrals are artefacts of this kind.

FIG 1.4 ‘Comparison of the space of free movement of child and adult. The actual activity regions are represented. The accessible regions are blank; the inaccessible shaded, (a) The space of free movement of the child includes the regions 1–6, representing activities such as getting into the movies at children’s rates, belonging to a boy’s club, etc. The regions 7–35 are not accessible, representing activities such as driving a car, writing cheques for purchases, political activities, performance of adults’occupations, etc. (b) The adult space of free movement is considerably wider, although it too is bounded by regions of activities inaccessible to the adult, such as shooting his enemy or entering activities beyond his social or intellectual capacity (represented by regions including 29–35). Some of the regions accessible to the child are not accessible to the adult, for instance, getting into the movies at children’s rates, or doing things socially taboo for an adult which are permitted to the child (represented by regions 1 and 5).’

The developing environment or life-space of a human culture may be compared with the changing life-space of a child, as viewed by the topological psychologist. As the culture evolves new adaptive means of exploring and using the environment, this environment is effectively enlarged. Yet the loss of specialist skills—of the hunter, for instance—may effectively close off regions of the environment which were formerly open (after Lewin).

Certain areas in the environment of the hunter may no longer be accessible to civilised man: 1 and 6 may be taken to refer to skills in collecting certain animals and plants, or craftsmanship in chipped stone which may have been lost between the Upper Palaeolithic and the Early Dynastic period, effectively closing off parts of the potential environment. This image of the life-space of man can be extended into the other dimensions of the environment, referring to the whole field of social activities as well as activities relating to the natural component of the environment. It takes little reflection to see how many new social and religious relationships, for instance, become possible in a more ‘advanced’ society; the environment is enlarged in several dimensions.

It is now possible” to make a statement about civilisations which does not seek to define them in terms of a single principal culture trait, or even polythetically, in terms of, for example, two out of three traits. Nor does it appeal to ‘form’ or ‘culture style’. We can see the process of the growth of a civilisation as the gradual creation by man of a larger and more complex environment, not only in the natural field through increasing exploitation of a wider range of resources of the ecosystem, but also in the social and spiritual fields. And, whereas the savage hunter lives in an environment not so different in many ways from that of other animals, although enlarged already by the use of language and of a whole range of other artefacts in the culture, civilised man lives in an environment very much of his own creation. Civilisation, in this sense, is the self-made environment of man, which he has fashioned to insulate himself from the primaeval environment of nature alone. All the artefacts which he uses serve as intermediaries between himself and this natural environment and, in creating civilisation, he spins, so to speak, a web of culture so complex and so dense that most of his activities now relate to this artificial environment rather than directly to the fundamentally natural one.

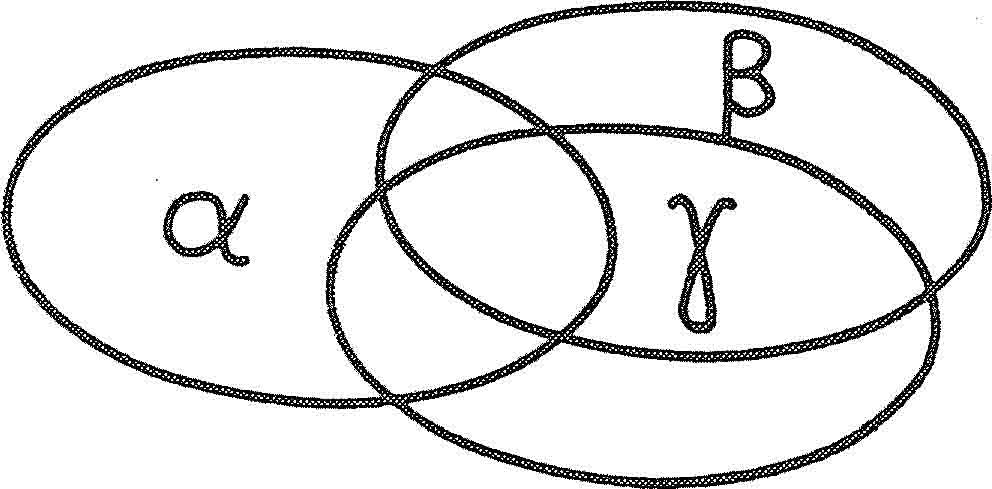

FIG 1.5 The effective insulation of man from nature by means of the artefacts which he creates. His activities (β) are largely related to artefacts (γ), and his contacts with nature (α) nearly always involve their mediation.

If we consider life in a Minoan palace, for instance, the material dimension of the environment represents a considerable enlargement on that of the neolithic villager, although in both the man-made environment mediates to some extent between man and nature. In the palace, for instance, there was running water, drainage, toilets even, and provision for light and heat (fig. 21.3). The decoration and art were the product of skill and the subject of admiration, and this represents a new man-artefact relationship, an enlargement of the environment.

The throne room at Knossos is the symbol of the enlarged social environment of each member of society, where social stratification and craft specialisation introduced new relationships between men. The Sumerian religion (which is better understood than the Minoan) substituted an explicit cosmology, rationalising the world by its objectifications, and allowing man to participate in efficient maintenance of the world order. Such a religion is a projection by man, an artefact, which mediates (or is believed to mediate, which in this context is the same thing) between himself and the observed realities of nature.

Writing itself, man’s subtlest artefact, not only permits new kinds of communication from man to man (and, hence, new relationships). In a temple or palace economy it allows new man-artefact relations: the store of products (artefacts) and foodstuffs (many of them also in a sense artefacts) can now take place on a more systematic basis. When used for calendrical purposes, writing permits predictive astronomy, and thus again is artefact mediating between man and nature.

A developed art style is also an improved form of communication: like writing it transmits information symbolically. And, as in writing, the symbol does not have to be representationally complete. The colossal statue of an Egyptian Pharaoh with his emblems of kingship is, by virtue of its convention, intelligible to all members of Egyptian civilisation as a statement about the social order (as well as the religious order). The symbolism of power and kingship is part of the human environment in all highly ordered societies. The development of these coherent systems which we may term projective or symbolic,—writing, a coherent art style, and a framework of religious beliefs—is something seen already, to a considerable extent, in all human societies, and in a much more developed form in all civilisations. As Ernst Cassirer has observed, ‘The functional circle of man is not only quantitatively enlarged; it has also undergone a qualitative change. Man has, as it were, discovered a new method of adapting himself to his environment. Between the receptor system and the effector system, which are to be found in all animal species, we find in man a third link which we may describe as the symbolic system. This new acquisition transforms the whole of human life. As compared with the other animals man lives not merely in a broader reality; he lives, so to speak, in a new dimension of reality’ (1944, 24).

Here then is the created environment of man which, in a civilisation, takes on a new complexity. Not only is there a whole new range of material artefacts but these various symbolic artefacts of which Cassirer has written, the artefacts of the projective systems, also find expression in material form. It is now that we see a written language; it is now that we see temples as visual symbols of man’s religious beliefs, and palaces as a concrete expression of his social order. Robert Redfield, in his admirable book The Primitive World and its Transformations, likewise stressed the importance of the nonmaterial aspects of culture and described the progress from what he termed ‘the primary condition of mankind’ to civilisation as a series of ‘great transformations’. ‘The great transformations of humanity are only in part reported in terms of the revolutions in technology with resulting increase in the number of people living together. There have also occurred changes in the thinking and valuing of men which may also be called “radical and indeed revolutionary innovations”. Like changes in the technical order these changes in the intellectual and moral habits of men become themselves generative of far-reaching changes in the nature of human living’ (1953, 24).

Civilisation can be compared to a space rocket: the men within it are to a large extent encapsulated, insulated from direct contact with nature. The problems of securing food and shelter, although they are present, are now eclipsed by other preoccupations which could not exist outside of this civilisation.

Of course not every participant of a civilisation is insulated so effectively as the Minoan prince in his palace. The large proportion of agricultural workers have a life in many ways similar to those of a neolithic community or to a modern ‘folk’ society. But the existence of the palace or the city, and the social and religious contacts which these people have with it, make them members of civilisation and enlarge their environment just as the environment of all men is enlarged by the first man to set foot upon the moon.

In an attempt to match the concision of Leslie White’s definition of culture as ‘man’s extra-somatic means of adaptation’ this position may be summarised: Civilisation is the complex artificial environment of man; it is the insulation created by man, an artefact which mediates between himself and the world of nature. Since man’s environment is multi-dimensional so too is civilisation.

This definition is, of course, not an operational one: defining criteria such as Kluckhohn’s have to be chosen. It may thus be entirely satisfactory to say ‘civilisation is a constantly recurring assemblage of artefacts including two out of three of the following: written records, ceremonial centres, cities of at least 5,000 inhabitants’, but this is only an operationally effective way of saying ‘a civilisation is a constantly recurring assemblage of artefacts documenting a human environment effectively insulating the individual from the world of nature’. It seems logical to select as criteria the three most powerful insulators, namely ceremonial centres (insulators against the unknown), writing (an insulator against time), and the city (the great container, spatially defined, the insulator against the outside).

This definition expresses what all these various and agreed defining features—writing, cities and so forth—have in common. It makes clear why these are important criteria, where metal-working, for instance, although not irrelevant, is something of a technological detail. We see, too, how the celebrants in a Maya temple were much more thoroughly encapsulated in an environment of their own construction than the sun-watchers of Stonehenge. Both, of course, were far from the palaeolithic cave-painter who, for a brief moment, created a world of his own before emerging into the harsher reality of day.

A man born into the world is shaped by his environment. We may say that civilisation, like language, ‘far from being simply a technique of communication, is itself a way of directing the perception of its speakers and it provides for them habitual moulds which analyse experience into significant categories’ (cf. Dobzhansky 1962, 71). Culture has been regarded as ‘patterned behaviour’, but with the behaviour patterns which he learns the civilised man or child inherits a ready-made world-view: we are all children of our time. And yet, on the other hand, civilisation and this world view are made by man. The situation is like the old parable, ‘Which came first, the chicken or the egg?’, which has a structure analogous to ‘The child is father of the man’. In the case of a civilisation the situation is continuous; both man and civilisation coexist and they influence each other mutually. There is ‘feedback’. As we shall see in the next chapter, the feedback is positive. As Sapir put it, again speaking of language: ‘the instrument refines the product, the product refines the instrument’ (Dobzhansky 1962, 210). That is what Gordon Childe understood so well when he called his study of the origins of civilisation Man makes Himself.