November 1911: The Pinnacle

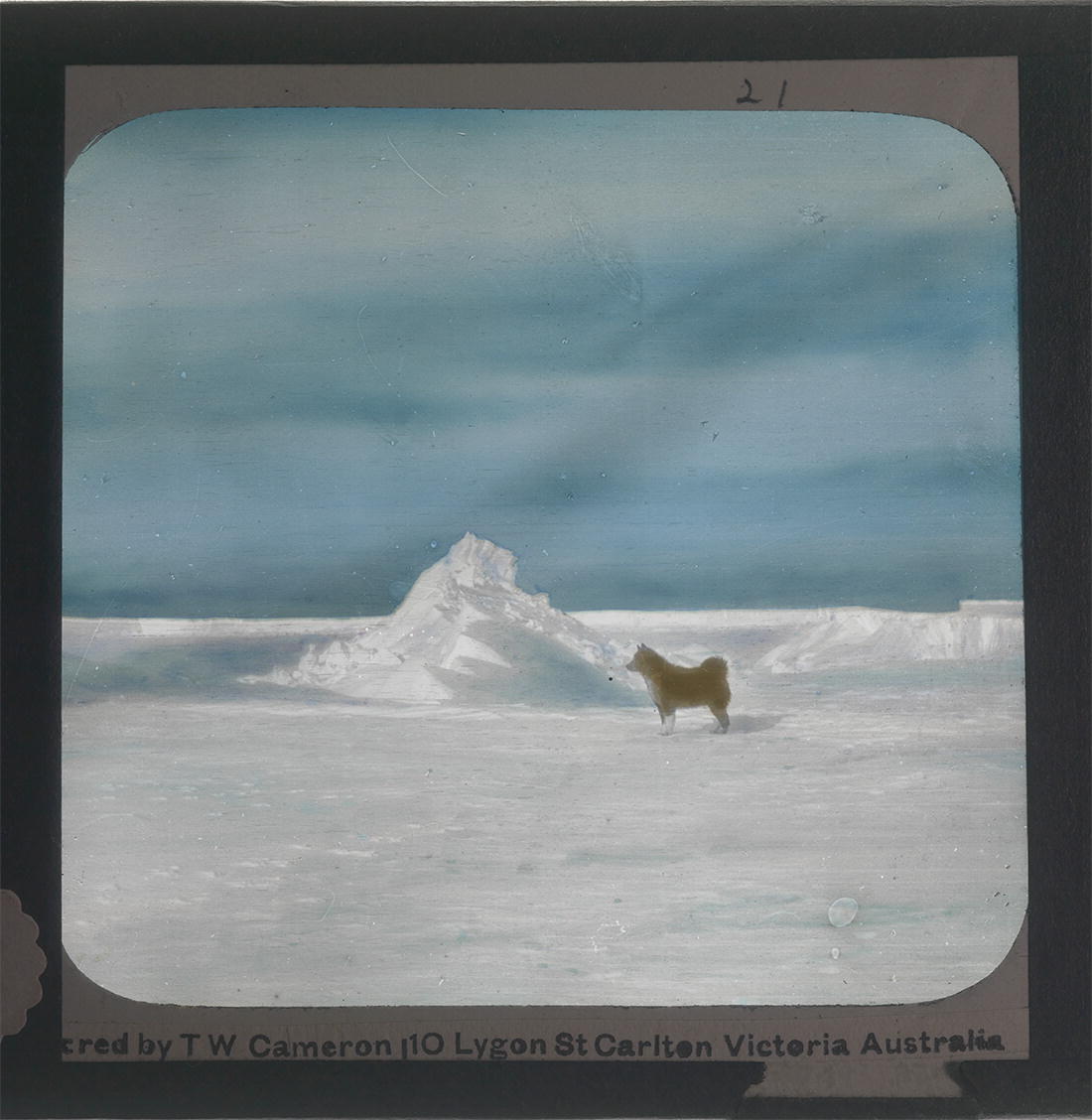

In the pristine whiteness, the vast alien land that was Antarctica, high atop a plateau that reached 10,000 feet into the clear and dazzlingly blue sky beyond, the sled dogs faithfully pulled their burdens.

Threading their way between the magnificent ice-crowned peaks of the Transantarctic Mountains, they faithfully ascended the treacherous glacier that met the Polar plateau. Here the lofty outlook led to the last undiscovered place on earth, which now awaited them – the South Pole.

The Greenland dogs, finding themselves at the opposite end of the earth from whence they had come, had admirably accomplished their task. Vital and loyal to the last, they had climbed and pulled with all their heart and all their might, their desire to please motivating them, and their instinct to run and pull spurring them on. They were working for their men, striving to achieve their humans’ goal: to reach the destination ahead. Their only anticipated reward was a little attention from their human companions – an acknowledgment of their loyalty and prowess, a thankful gesture, a morsel for a job well done.

The explorer understood the dogs’ loyalty and commitment. He knew of their power to make him the first human to reach this coveted spot on this alien land. He sensed their strong desire to run and pull, to attain his affection, to help him attain his goal. And he was prepared to reward them.

The reward he had in mind, however, was a different one. It awaited the dogs there – on the plateau – at the South Pole.

1897: Of Meat and Men – Lessons from the Belgica

It must be remembered that Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen had ventured into the Antarctic well before Robert Falcon Scott or Ernest Shackleton had done so, sailing on the Belgica with Dr. Frederick A. Cook and Commander Adrien de Gerlache as part of the Belgian expedition of 1897–1899, at the age of 25, and becoming one of the first people to overwinter in the Antarctic – albeit unwittingly, as his ship had become trapped in the ice, frozen in the Bellingshausen sea off Graham Land along the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Although it was the first expedition to spend a winter in Antarctica, the crew spent those 13 months (from February 1898 to March 1899) on board the ship, nearly starving, succumbing to scurvy (due to a lack of vitamin C), and diving into near madness. The commander, captain, and most of the crew became deathly ill – indeed, some became mentally unsound. They were ill-equipped, they were not prepared for the endless ice and the never-ending nights of winter, and they suffered from malnutrition. One crewmember tragically died. The commander himself slipped into insanity.

It was the Norwegian first mate, Roald Amundsen, and the American doctor, Frederick Cook, who helped save the men. Amundsen and Cook administered a protein diet of fresh meat that they reaped from the freshly killed seals and penguins they hunted on the surrounding ice. To Amundsen’s great annoyance, the commander at first would not eat the meat and further gave orders that no one else be allowed to eat it. Following the incapacitation of both the commander and the captain, however, Amundsen took official command and fed the meat of the now-frozen seals and penguins to the crew. The meat, according to Amundsen, made all the difference, and the crew’s physical and mental health immediately was altered for the better. Subsequently, an ambitious plan to dynamite their way out of the ice, devised by Dr. Cook, was successful, and the ship returned from Antarctica. It was Amundsen’s fervent belief that Dr. Cook’s positive perseverance and wise instruction to eat seal and penguin meat helped the crew to survive (Amundsen [1927] 2008).

Amundsen himself exhibited a cool head in the face of near-death and ice-locked insanity and most likely gained a new-found appreciation for (and possibly addiction to) fresh meat – one that he would carry with him through the rest of his exploration days. He also gained from the experience of being part of the first expedition to utilize sledges on the Antarctic ice, which he did with fellow Northern ice veteran Dr. Cook. Despite the grueling aspects of the year-long ice entrapment in Antarctica, Amundsen learned a great deal from this expedition. He learned about the disadvantages of having two commanders of an expedition – one who was captain of the ship and one who was the leader of the expedition. He learned about the importance of preparedness – both mental and physical. And he learned about what he deemed as the necessity of eating meat, to stave off scurvy and mental degradation.

Amundsen probably also learned that it would have been most helpful to bring along dogs as part of the expedition, in order to allow a real sledging journey to take place across the Antarctic ice. Unbeknownst to him, at that very same time in Antarctica, in February 1899, a fellow Norwegian named Carsten Borchgrevink was bringing the very first sled dogs to work on the Antarctic continent. Arriving on his Southern Cross ship as part of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1898–1900, Borchgrevink would become the first to overwinter on the continent itself and would conduct the first-ever dog-sled journey in Antarctica.

September 1899: The Dogfight About Using Dogs

A mere several months after Amundsen’s return from Antarctica, the Seventh International Geographical Congress was taking place in Berlin, Germany. It was late September 1899, and the prestigious gathering comprised a veritable “Who’s Who” in the science, geography, and Polar exploration fields. A mandate was given for international exploration in Antarctica, with the South Pole being targeted as a particularly coveted goal to reach (Royal Geographical Society 1899). Thus, the race was officially on among the participating countries.

During the prestigious proceedings, a virtual heated debate regarding the use of dogs for Polar exploration took place between two exalted members of the exploration community: British geographer and esteemed Royal Geographical Society president Sir Clements R. Markham and Norwegian professor and legendary Polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen. Markham spoke vehemently against the practice of using dogs, calling it “a very cruel system,” citing unnecessary “cruelty” to the animals as they are worked to death, starved, or killed for dog food and expounding on the superiority of men in achieving exploration on their own (Markham 1899a, 475–476, 1899b, 625). Nansen strongly advocated for the practice of using dogs, citing his own experience with dogs in the Arctic, as well as their ability to enable the explorer to successfully conduct scientific study, and arguing that overtaxing the dog is better than the “cruelty” of overtaxing a human being; “it is terrible, gruesome to kill the dogs,” he stated, and then added, “But at home, we also kill animals” 1 (Nansen 1899, 76–77).

It must be kept in mind that Professor Fridtjof Nansen had indeed used dogs in this manner. The scientist, by now 38 years of age, had invented the ice drifting method (in 1884) – wherein one allows their ship to become frozen in the ice pack and to drift with the ice toward their Polar destination, and he had designed the Polar vessel Fram (in 1893) – with its rounded hull structure that lifts under the pressure of the ice, in which he had successfully drifted across the Arctic Ocean in 1893. During that expedition, he had reached the farthest north of that time – 86° 14′ N – in 1895, crossing the Arctic ice on foot and using 27 sled dogs (Markham 1896). His companion on that Arctic expedition was Hjalmar Johansen, who would later accompany Amundsen to the Antarctic and arguably become his foil.

Nansen practiced the teachings of the original Arctic dwellers – the Inuit – by using the pulling power of dogs to mobilize his sleds. But to this method, however, he added one standout strategy – the killing and eating of the dogs. The dogs would serve as transportation and then as fuel for himself and for the remainder of his transportation. As the dogs grew exhausted and weaker, they would be fed to the other dogs, leaving the strongest to be eaten last as the ultimate destination was approached. In this manner, Nansen’s 27 dogs had dwindled to 2.

And, so, the lines were drawn, and the race was on, at this International Congress. The matter in question was: cruelty to dogs or cruelty to humans. But the truer question is, was this a false either-or choice? Could the victory be accomplished without the brutality of the price of its accomplishment? Both Markham’s and Nansen’s schools of thought seemed to indicate no. This academic debate would soon materialize into a very real and essential context – a contest of will and survival, a question of efficiency and morality, a true race to the death.

1903: South by Northwest – The Gjoa Expedition

A year after the International Congress in Berlin, Robert Falcon Scott was selected to lead the British to the Antarctic and its coveted South Pole. At 33, the young naval officer was accompanied by a 26-year old Ernest Shackleton as part of the British National Antarctic Expedition. Both Scott and Shackleton exhibited full agreement with Clements Markham in taking a stand against the reliance upon dogs, using them unhappily and ineffectually during the Discovery expedition of 1901–1904. Despite Nansen’s counseling, ponies were their preference, but the ponies sank in the snow with each step they took. Along with the misunderstanding of how to drive the dogs, Scott failed in his first attempt to reach the South Pole.

Amundsen, on the other hand, followed his mentor Nansen’s belief in dogs and, after earning his skipper’s license in 1900, employed sled dogs on his Gjoa expedition of 1903–1906, during which he succeeded in locating the magnetic North Pole, and became the first to successfully cross the Northwest Passage.

On this historic navigating mission, Amundsen took with him 6 veteran sled dogs from Norway and picked up 12 more along the way – at Godhavn near Disko Island – which he purchased from the Royal Danish Greenland Trading Company (Amundsen 1907). The six original dogs, said Amundsen in a speech later given to the Royal Geographical Society in London, “seemed to enjoy the voyage exceedingly, running about and getting into as much mischief as was to be attained. Their spirits were particularly high on rough days, as then they had an agreeable change in their otherwise somewhat monotonous diet …, in the shape of the delicious viands sacrificed to them by my seasick companions” (Amundsen 1907, 488–489). He also cited the importance of shooting seals along the way for “fresh meat” for both the crewmen and the sled dogs.

The crewmen of the Gjoa accompanying Amundsen on this expedition included Helmer Hanssen and Adolf Henrik Lindstrøm, who would later also accompany Amundsen to the Antarctic.

As part of this Northwest Passage expedition, Amundsen and his crew lived for 2 years with the Inuit on King William Island, learning important skills from the indigenous peoples of the Canadian Arctic, including how to drive dogs on long sledging journeys. He came to know the ways of both the “Ogluli Eskimo” and the Netsilik, whom he called “Nechjilli Eskimo” and with whom he formed a special friendship (Amundsen 1907, 495).

Amundsen arrived at Gjoa Harbor in September 1903, and his intensive education commenced, with the Inuit community teaching him the importance of light and warm reindeer-skin clothing, protective snow huts, and proper driving techniques for sled dogs. A 3-month sledging excursion to locate the magnetic North Pole in early 1904 required a sufficient team of sled dogs, most of whom had not survived the winter on King William Island. Amundsen found it difficult to do his work without them and so obtained ten more sled dogs from the few visiting ships, including a Canadian vessel, calling in at his harbor (Amundsen 1907).

After 2 years of perfecting his skills, he bid farewell to King William Island in August 1905 and proceeded west, making short work of the actual crossing of the Northwest Passage, which he was able to do in 1 week. Another year frozen in at King Point – during which he spent more time with indigenous peoples – resulted in his completing the crossing in August 1906.

A fact he did not mention in his speech to the Royal Geographical Society, but which he later illustrated in his autobiography, is the manner in which he celebrated the crossing of the Northwest Passage. Having been unable to eat or sleep during the three torturous weeks in which the ship delicately navigated the treacherously shallow, narrow, and winding water channels, Amundsen finally rewarded himself with frozen, raw caribou meat which he frantically cut down from the rigging, “thrusting it down my throat in chunks and ribbons, like a famished animal” (Amundsen [1927] 2008, 35–36). Only then did Amundsen regain his calm composure. As it had on the Belgica, meat, it seems, still played a large role in Amundsen’s sense of wellness and, in his mind, was associated with calmness. This association would continue during his Antarctic expedition.

The speech at the Royal Geographical Society, in which he recounted his Northwest Passage expedition, was given in February 1907, 6 months after Amundsen’s return. In it, Amundsen spends more time regaling his audience with adventurous tales about the sled dogs, and describing his time on land with the Inuit, than illustrating the actual crossing of the Passage. It is a reflection of the importance he placed on surveying the North Pole region and his dependence on the dogs to help him do so.

Amundsen’s speech incorporated modesty and efficiency. He credited those who had come before him. He offered maps and lantern slides for visual illustration. Tall and blue-eyed, and always appearing calm and elegant in film footage taken of him in later years, he must have exuded a cool air of confidence and intelligence. This striking Viking had accomplished what no one else had been able to do in over four centuries – cross the Northwest Passage – and he had located the magnetic North Pole as a bonus. But despite his achievements, his assured and graceful demeanor, and his mastery of marketing, Amundsen was upstaged that night. For at this same time, England’s own son – Ernest Shackleton – made an earth-shattering announcement of his own: he intended to lead an expedition to the South Pole. The announcement greatly captured the public’s imagination.

1908: Ponies and Huskies and Kings

The year 1908 marked the 3-year anniversary of Norway’s independence. During Amundsen’s absence in the Northwest Passage in 1905, Norway’s King Oscar II of Sweden had been replaced by King Haakon VII from Denmark. The tiny country was on the map again. There was a new patriotic pride among the people, and these Arctic exploration feats of achievement could be inducted as part of the national identity. Moreover, the explorers doing the achieving were being treated as rock stars. In these explorers were embodied the qualities of glamour, talent, celebrity, and legendary triumphs. And, so, it was a good time for another Norwegian victory.

It is with extreme regret that I realize that I cannot be present on that occasion as I shall then be at sea. I would like to take this opportunity to express my admiration for the great work which Captain Amundsen has done, and the voyage performed by his gallant little ‘Gjoa’ and pay tribute to his difficulties overcome. The true meaning of his work is most apparent to those who have encountered similar experiences as a polar explorer. Therefore I wish to express my sincerest admiration for the courage and persistence displayed by Captain Amundsen and for the splendid result which he has achieved. 2

By the time of this dinner, February 1908, Ernest Shackleton himself was making good on his announcement given at the time of Amundsen’s Royal Geographical Society presentation in February of the previous year. He and his ship the Nimrod had already set sail for Antarctica in August 1907. Among his expedition members was a young Australian scientist named Douglas Mawson. Shackleton was determined to succeed where Scott had failed. For his foray to the South Pole, he had taken with him primarily Manchurian ponies.

It was during this year that Amundsen appealed to Nansen to allow him to use his beloved ship Fram for a trailblazing new excursion. With his Northwest Passage victory and Belgica Antarctica overwintering experiences both firmly tucked under his belt, Amundsen now announced a new goal, one that was as audacious, impressive, and ambitious as his previous ones. He would make an attack on the Pole itself – the Geographic North Pole. Amundsen’s plan was to travel east to west, beginning at the Bering Strait, drift along the Polar currents, find the Geographic North Pole, and continue to sail across the Arctic sea.

Many months of submittals and approvals followed. Nansen agreed to Amundsen’s request, and Norway’s King approved of the expedition. Amundsen sought endorsement from the Royal Geographical Society, writing to its secretary J. Scott Keltie, and received encouragement and support (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence RGS). Early the following year, the Norwegian Storting (Parliament) granted the funds for the venture. 3 In February of 1909, Amundsen delivered a speech to the Royal Geographical Society about the upcoming North Pole expedition, making his intentions public.

In the following month, March 1909, news reached the world that Shackleton was returning from Antarctica just short of his goal – he had stopped a mere 97 miles from the South Pole. Most of his ponies had died, and the dogs were used only as reserves, leaving him and his men to pull their own sledges. Still, the achievement was monumental. His trek had established a farthest south of 88° 23′, earning him the title of Sir Ernest Shackleton upon his return to England. Amundsen praised Shackleton immensely, writing to Keltie of his admiration for the Englishman, whom he now saw as the principal and primary explorer of the south. 4 But perhaps, in the back of his mind, Amundsen also wondered if Shackleton would not have gladly exchanged his knighthood for a 90°-South title and perhaps further thought that he would have been king had he but used a team of dogs.

Amundsen pursued his own plans for his North Pole expedition over the next several months, overseeing the ship’s repairs, hand-selecting a crew, and preparing to purchase dogs (Amundsen 1912). Dogs were the best draft animals on ice and snow, he later wrote in his autobiography; they were strong and smart, able to navigate any surface that humans could cross (Amundsen [1927] 2008). For his crew, he chose trusted acquaintances and former expedition companions – only one member was closer to Nansen than to Amundsen, and that was Hjalmar Johansen, Nansen’s companion in the Arctic.

By early September of that year, 1909, the Fram was in the last stages of being refurbished, and Amundsen had selected his crew – most importantly, he had carefully recruited experienced dog drivers, for dogs were to be a vital component of his mission to become the first explorer to reach the North Pole.

At this moment, however, the worst news hit Amundsen: the North Pole had been reached – not once, but twice, by two American colleagues, who each claimed to have been the first at the Pole: Amundsen’s great friend and Belgica shipmate Dr. Frederick Cook (in April 1908) and Admiral Robert E. Peary (in April 1909). The news summarily stole Amundsen’s thunder. The discovery, in his view, made his expedition redundant. Funding would fall off, he surmised. Sponsors would lose interest (Amundsen 1912; Amundsen [1927] 2008). Nansen, most likely, would have reminded him that this was purely a scientific excursion, not a race or a contest. J. Scott Keltie, who was always scientifically minded, saw the overshadowing effect this would make on Amundsen in the public realm and, in a response letter to Amundsen’s brother Leon, would later write that the chances of receiving large sums of money from newspapers for advance news about Amundsen’s expedition were now greatly reduced. 5 For Amundsen, his true concerns were financial support and public interest.

The North Pole was taken.

Dr. Cook, it seemed, still had some tricks up his sleeve – he was still eating the meat.

The North Pole had been claimed – twice over, no less. Yet the English knight had returned from the south, with that title unclaimed.

If one were to trace a line from the North Pole down the Atlantic, to the southern tip of Argentina, then south and east past the Cape of Good Horn, and across the boundary of the Antarctic circle, then east to the Ross Sea, and a little further south, one may end up … at a new discovery. Perhaps this is how Amundsen’s mind flipped from the north to the south. Perhaps this is how his thoughts plunged from the North Pole to the South Pole, repelling from one end of the earth to the other, racing down the Atlantic to the opposite axis of the world. It was an audacious decision. It would be a “sensational” endeavor indeed (Amundsen [1927] 2008, 41). And it would require dogs.

And, so, the story of the 116 sled dogs begins.

A Greenland dog in Antarctica – a member of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition of 1910–1912 and one of the 116 sled dogs who helped Roald Amundsen reach the South Pole. (Photographer: unidentified/Owner: National Library of Norway)

Roald Amundsen, fresh off the Belgica expedition, and already a veteran of Antarctic exploration, poses for a portrait in June 1899, dressed in his Inuit-inspired Arctic clothing that would later be utilized during his sled dog-pulled sledging excursion to the South Pole. (Photographer: Daniel Georg Nyblin/Owner: National Library of Norway)

An iceberg off the Antarctic Peninsula – much like the first icebergs seen by Roald Amundsen during his Belgica expedition, prior to his being frozen in over the winter. (Photograph by Mary R. Tahan)

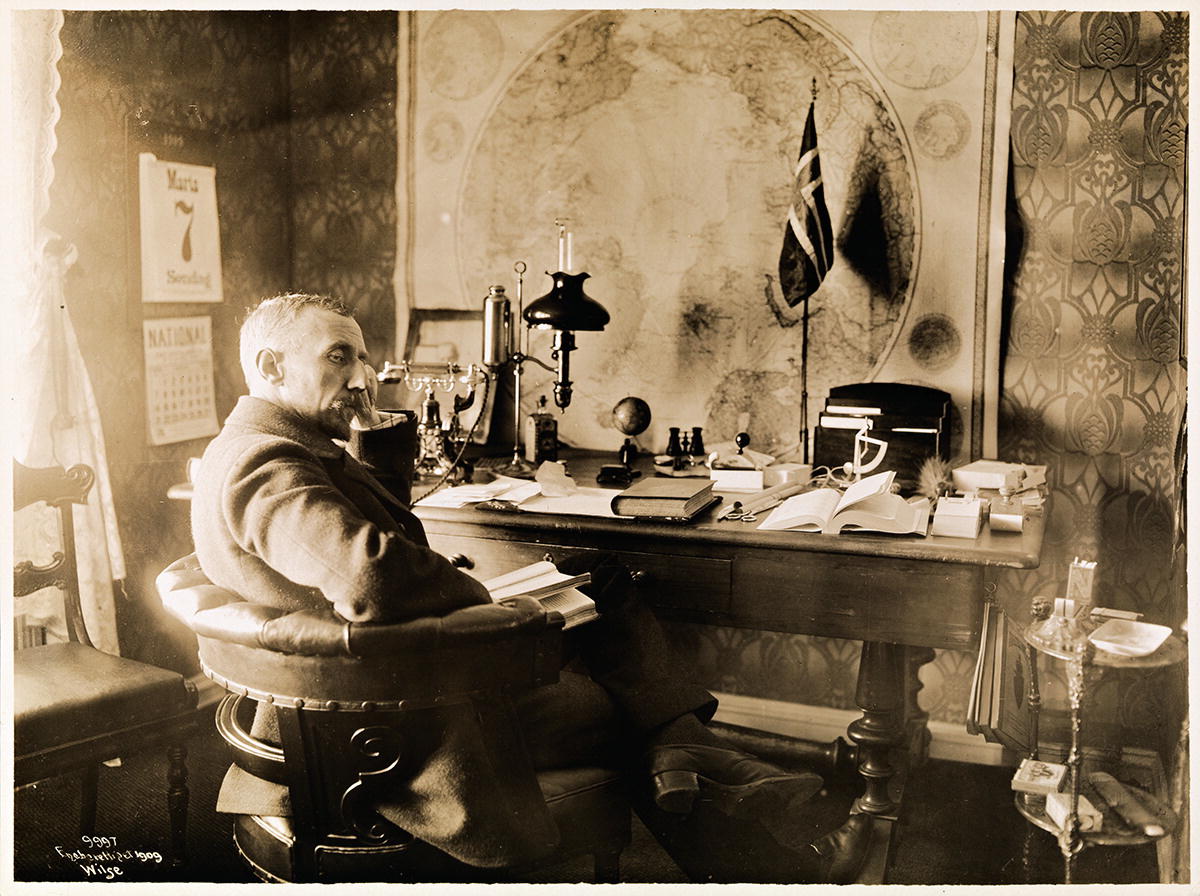

Roald Amundsen in his home office in Svartskog on March 7, 1909 – as indicated by the wall calendar to his left – most likely planning his trip to the North Pole. This photo was taken several months before the news of the North Pole’s discovery reached him in September 1909. Note one of the large Polar maps hanging on the wall in front of his desk. (Photographer: Anders Beer Wilse/Owner: National Library of Norway)

A large map of Antarctica, showing the white continent geographically placed at the center of the globe, still hangs in Roald Amundsen’s home office today, at “Uranienborg” near Oslo. (Photograph by Mary R. Tahan)

Notes on Original and Unpublished Sources

- 1.

(Translated from German for the author by Nina Korbu during the author’s research at the National Library of Norway)

- 2.

R.F. Scott to Den Norske Klub, 10 June 1907, NB Brevs. 812:1, Manuscripts Collection, National Library of Norway, Oslo

- 3.

R. Amundsen to J.S. Keltie, 13 February 1909, ar RGS/CB7/Amundsen, Archive Material, RGS-IBG Collections, Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London

- 4.

R. Amundsen to J.S. Keltie, 25 March 1909, ar RGS/CB7/Amundsen, Archive Material, RGS-IBG Collections, Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London

- 5.

J.S. Keltie to L. Amundsen, 7 October 1909, ar RGS/CB7/Amundsen, Archive Material, RGS-IBG Collections, Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London

- 6.

Stein Barli, director, Follo Museum, conversation with the author, during private tour of Roald Amundsen’s Home in Svartskog, Norway, 12 March 2011

- 7.

Observations made during the author’s private tours of Roald Amundsen’s Home in Svartskog, Norway, 12 March 2011 and 25 August 2012