Home Is Where the Frozen Heart Is

The surviving 34 sled dogs who returned to Framheim from the month-long, arduous second depot tour did not look like the same dogs who had left. They were skinny, sore, and starving, but they would soon be on the road to recovery, for now they could rest and feast to their heart’s desire. Their stoicism upon returning to camp, and resilience in recovering, amazed Roald Amundsen. Of particular interest to him was watching their “home-coming” – especially that of his favorite dog, Lasse, who was the sole survivor from Amundsen’s team during the second depot tour (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 252).

Lasse (also Lassessen) was part of the trio of Lasse, Fix, and Snuppesen. He was a magnificent black beauty who was strong and hearty – although now he was thinner than usual. Snuppesen was female and smaller, and possibly that may be why she had not been taken on this depot run – Amundsen did not say. As for Fix, he had not been chosen because Amundsen felt that he had not looked up to the task at the time that they had left – meaning most likely that he was not hefty enough for the type of work they would be doing. Now, however, a month later, Fix was quite rotund and sturdy, as he had been well fed, and he liked to eat. In the dynamics between Lasse and Fix, as interpreted by Amundsen, Lasse was the dominant one, and Fix was his follower. Therefore, Amundsen wanted to see how these two would reunite, when the condition of their physiques had been reversed – Fix was now the stronger-looking dog, and Lasse the weaker. “Would not Fix take advantage of the occasion to assume the position of boss?” wondered Amundsen, as he watched “with intense curiosity.” It took a little while for the two friends to spot each other among all the other dogs, but when they did, “it was quite touching,” wrote Amundsen (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 252–253):

Fix ran straight up to the other, began to lick him, and showed every sign of the greatest affection and joy at seeing him again. Lassesen, on his part, took it all with a very superior air, as befits a boss. Without further ceremony, he rolled his fat friend in the snow and stood over him for a while – no doubt to let him know that he was still absolute master, beyond dispute. Poor Fix! – he looked quite crestfallen. But this did not last long; he soon avenged himself on the other, knowing that he could tackle him with safety.

The question of who was master, among dogs and humans, was quite paramount to Amundsen and the answer quite absolute. Around Framheim, Amundsen was boss. He was the uncontested ruler. And so, despite any possible mistakes made on his part, or inefficiencies shown by him, or injuries suffered as a result, Amundsen still ruled, no matter what.

As if making an attempt to make up for what had happened on the second depot tour, Amundsen made it a point in his diary, on March 23, 1911, to say (Amundsen expedition diary): “The home-remaining dogs [who did not go on the second depot tour] have been very well cared for. We now have in all 107 dogs – of which 85 [are] adults & 22 [are] puppies. But all these puppies are now already so big and well-fed – fat like Christmas pigs – that they will be perfectly ready for use in spring.” 1

It was as he had hoped – there were puppies being fattened up and made ready to help provide transportation over the Antarctic ice, not to mention the adult standby dogs who were ready to take over for the eight who had died on this second tour. Yes, his system of building in redundancy and employing usable progeny – that is, bringing double the amount of adult dogs from Greenland and raising trainable puppies on board the ship – was now coming into play and proving the merits of his methodical thinking.

Moreover, both dogs and men were supplied with enough dog food and seal meat to last them through the spring trek to the South Pole, which would take place after winter. Amundsen’s intent was to have 1200 kilos of seal meat stored and available at the first depot at 80° well before winter began. The main reason for all this seal meat at the first depot was the dogs. “It’s my intention to feed the animals abundantly there, when we reach it in the spring,” wrote Amundsen, as he felt that the first leg of the South Pole trip – the “Route to 80°” – was the most arduous and energy-consuming, and therefore it was crucial that the sled dogs be able to depart from there well-fed, nourished, and satiated so that they could carry on the rest of the trip: “This tour will be the crown on our autumn work – in truth, a masterpiece, if I say so myself.” 2

Amundsen’s self-congratulations were noted. He had devised a plan to have enough food over the winter and throughout the South Pole trek – over 150 seals had given their lives for this, and he would make sure to have enough food waiting at the first depot – 80° – to enable the dogs to replenish themselves thoroughly after the first exhausting leg of the trip. He had learned well from the trials and tribulations of the second depot tour, and he would not repeat the mistake of not having enough food for the dogs to proceed comfortably beyond 80°. For it was the distance after 80° that would place him close to the Pole and the middle leg of the trek was of paramount importance.

For this purpose, Amundsen would initiate a third and final depot tour, one where the men would deposit one-and-a-quarter tons of seal meat at that first depot of 80°. This was crucial. He wanted the dogs to be as fattened up for the Pole trek as a pig is fattened up for Christmas – he had made this clear in his March 23 diary entry upon returning from his second depot tour. And he reiterated the statement in his book The South Pole: “How immensely important it would be on the main journey if we could give our dogs as much seal meat as they could eat at 80° S.; we all saw the importance of this, and were eager to carry it out” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 251). It was not the return but the start that he considered crucial for the dogs. The object was to get as many dogs as possible, in the best shape as possible, to the middle portion of the trek between 80° South and the Pole. The reasoning for this will be made even more clear at the time of the trek to the South Pole.

Unfortunately, Amundsen would not be able to participate in the third tour to depot 80° himself. Though he did not mention this in his book, his diary is full of the reason why he could not venture out with his men this time. A “sore” in his “intestinal rectum,” which he had sustained while conducting a sled journey during his Gjoa Northwest Passage expedition, most likely on King William Island, had reopened during the second depot tour and had been tormenting him, inflicting upon him “unbearable pain throughout the month we have been out,” explained Amundsen to his diary. 3 Although he was feeling better by this time – with the help of an enema – he was not yet ready for another long ride. He told Hjalmar Johansen as much and appointed that veteran Polar explorer as head of the third depot touring party – news which Johansen took well and to heart (Johansen Expedition Diary).

There was a feeling of comfort and belonging at Framheim. The Antarctic was the expedition members’ backyard. The puppies who had been reared on the ship reinforced that feeling of home on the ice. Amundsen had a profound sense of safety and well-being, aided by the presence of the dogs, and he admitted these feelings to his diary on March 25 in an emotional entry that he quoted, almost verbatim, in his book The South Pole (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 253–254):

I must frankly confess that I have never lived so well. And the consequence is that we are all in the best of health, and I feel certain that the whole enterprise will be crowned with success.

It is strange indeed here to go outside in the evening and see the cosy, warm lamp-light through the window of our little snow-covered hut, and to feel that this is our snug, comfortable home on the formidable and dreaded Barrier. All our little puppies – as round as Christmas pigs – are wandering about outside, and at night they lie in crowds about the door. They never take shelter under a roof at night. They must be hardy beasts. Some of them are so fat that they waddle just like geese.

Amundsen also enjoyed viewing the sights of the natural phenomena unfolding around him in his corner of the Antarctic, and he wrote about them in his diary and book (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 254). What must the aurora australis have looked like to the dogs on the evening of March 28, when Amundsen reported its sighting? The undulating pale greens and reds must have been reflected in their sphere-like eyes. Did they, too, like Amundsen, feel at home, gazing upon the opposite visual projection of their aurora borealis seen in the Arctic? The stars, visible through the aurora’s transparent layers of ribbons, appeared above a world of ice and snow inhabited by a community of canines, surrounding several specimens of another species who very much depended on them.

Amundsen was surrounded by his men, his dogs, and his puppies. He had never been happier. He was at home.

Johansen, too, described the homey feeling of Framheim and of its resident dog community (Johansen Expedition Diary). The sled dogs who had been on both depot tours, he observed, were significantly timid and undernourished upon first returning from the strenuous and exhausting cold trip. Gradually, however, they were becoming better, both physically and in disposition. Those other dogs who had stayed at home during the depot tours had become quite thick and fat and plump, but now their turn would come to make the exhausting trip.

On March 26, Amundsen made the announcement to his men regarding their undertaking a third depot tour and the necessity to deposit one ton of seal meat at 80° to fatten the dogs for their South Pole trek (Hassel 2011; Prestrud 2011). And on March 30, he officially made Johansen the leader of the men participating in the third depot tour. Amundsen gave Johansen this responsibility as “He is the oldest and most experienced.” 4 This delegating of leadership is noted in both Amundsen’s diary and Johansen’s diary on that day (Johansen Expedition Diary). Amundsen did not, however, mention Johansen’s leadership appointment in his book The South Pole, published after the expedition. Instead, in his book, he only made light mention of the fact that Johansen and Kristian Prestrud (and not in that order) decided to share a double sleeping bag together on their excursion, rather than a single one as all the other men had done (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 258). Whether this was some sort of veiled code is up for conjecture. Certainly, after the expedition, Amundsen and Johansen were not on the best of terms.

First, the third – and final – depot tour began. Johansen led a party of 7 men and 36 dogs with 6 sledges out onto the Great Ice Barrier and toward the 80° South depot (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 254–255; Amundsen Expedition Diary). The sledges were laden with over a ton of fresh seal meat that would be stored at this first depot, the gateway to the South Pole.

Second, all 69 dogs – adults and puppies – who remained at home camp (for two more had by now died, as will be seen) were now let loose. The 50 who had still been chained up to this time were now allowed to join their freed brethren and have the run of the camp and its surrounding environs. To keep the peace and promote fair and equal treatment, the men left one large pile of seal meat lying in the open on the snow, in which all the dogs partook. Their dining and dashing about was at times noisy, but, overall, peace prevailed. And, aside from the occasional small scuffle, harmony ensued among the dogs (Amundsen Expedition Diary).

The third important thing to happen on March 31, 1911, was that the British expedition’s Lieutenant Harry Pennell, who had formerly visited Framheim and the Fram and who was now captain of the Terra Nova ship, arrived in New Zealand and released the news that Amundsen, his men, his dogs, and the Fram were at the Bay of Whales. The news spread quickly around the world. Of particular interest to those who received this news was the number of dogs on the Norwegian expedition and whether the dogs would prove to be the game changer.

Lost in the Crevasses

Six teams of six dogs each, along with seven men, set out for the depot at 80° South on March 31, 1911. Every attempt had been made to take 36 fresh dogs and to leave the 34 who had returned from the disastrous second depot tour (Hassel 2011).

The party of men consisted of Hjalmar Johansen, Kristian Prestrud, Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Oscar Wisting, Jørgen Stubberud, and Sverre Hassel. Johansen was fully in charge. The 36 dogs were weighed down with the weight and the responsibility of transporting one-and-a-quarter tons of meat to the first depot on the Great Ice Barrier.

On the first day alone, the caravan traveled nearly 10 nautical miles with six heavily loaded sledges that, according to Johansen (Johansen Expedition Diary), were a “heavy burden.” 5 Johansen had borrowed two of Prestrud’s dogs – one of them named Cook – and they pulled his extremely heavy sled along with his own dogs Skalpen, Hellik, Emil, and Grim. Skalpen (“The Scalp”) had missed the previous (second) tour due to a sore leg, but now he was back in action, ready to do his part as he had done in the very first tour. Hellik was the now sturdy dog who at first had been timid and had hidden on the Fram and who was inseparable from his friend Skalpen. Emil was the philosophical scholar who persevered, and Grim was the “Unsundbäck” unhealthy dog who had survived and flourished under Johansen’s ministering hands. But the dogs were having a hard time pulling. On this first day, Johansen and his sled fell far behind the caravan, and the extreme effort caused him to be drenched with sweat and his clothes frozen stiff by the time he made camp at the end of the day’s work. One can imagine how the sled dogs felt after these herculean efforts as well.

Bjaaland concurred with Johansen’s account, reporting in his diary that Wisting’s, Johansen’s, and his own sled were so weighed down that all their dogs were struggling (Bjaaland 2011).

Hanssen, who had been sick at Framheim prior to leaving for this depot tour, braved the elements and the trip and marched along as best as he could with his dogs (Amundsen Expedition Diary; Johansen Expedition Diary).

The following day, Johansen reported trekking over hard, smooth snow, as the party attempted to negotiate the steep incline of the barrier, with both dogs and men having great difficulty with the heavy sleds. Johansen’s dog team was still in the back, and he found it necessary to give some of his load to the other sled teams. “All in all a rather tiring day,” wrote Johansen of that second day of the third depot trip. 6 Despite the cumbersome journey, the sled dogs traveled almost 12 nautical miles that day in −33° cold temperature.

On April 2, the party veered a bit further westward in their route than they had previously traveled, a fact that they discovered when they could not find their tracks from the second depot run. The dogs continued to pull, however, and were “quite willing with the heavy loads,” even if those loads were “heavier than we had them before,” noted Johansen. 7

On April 3, the men and the dogs found themselves in unfamiliar terrain, a bit off course from their normal route, and surrounded by thick snow and fog. Suddenly, the party came upon an area that was “a true jumble of crevasses,” according to Johansen – not that they could see them, however. 8 The cracks were invisible, hidden under snow bridges that looked to be solid surfaces, but, once crossed over, would fall away into wide open expanses that reached down into nothingness. These surfaces usually broke right behind the individual crossing them, and the width of the openings were large enough to swallow a sled, a man, and most definitely a dog.

As the party tried to correct their course and travel more to the east, Johansen’s sled suddenly fell into one of these crevasse openings; fortunately, however, the dogs had been able to cross over to the other side first, so that the men were able to push the sledge out of the crevasse and onto the solid ice. As they proceeded, Hanssen himself had a close encounter with one of these perilous crevasses; he was driving right behind Hassel, who had just crossed over with his dogs. As Hanssen followed, a split second after he had crossed the snow bridge, it crumpled right beneath his feet, revealing a crack that was 1 m wide and showed no bottom. Hanssen just barely made it over to the other side, narrowly escaping within an inch of his life.

Having gotten away from these hazards, the party proceeded forward but found that the crevasses were getting worse and worse. The cracks were everywhere. They crisscrossed in all directions and could not be seen until it was too late. Which is what happened next.

The party paused to ascertain the situation. Johansen’s sled stopped behind Hassel’s, and, according to Johansen, “the dogs lay down to rest.” 9 Before they knew it, a crack several feet wide suddenly opened right underneath them. Two of Johansen’s dogs, who were resting there, fell vertically through the snow, their harnesses snapped, and they were instantly sucked into a bottomless pit. All that could be heard was a distant howling. Instantly, they were gone.

The two dogs were Emil, the wise and patient student, and Hellik, the near-dead dog who had been brought back to life and now lived life with zest.

Johansen was devastated. He had nursed these two dogs back to health. They had stuck with him on the ship and on the ice, through thick and thin.

“2 of my dogs have been lost in a bottomless crack,” wrote Johansen despairingly in his diary. “… Emil and Hellik disappeared without a trace through the snow, as the harness-straps broke. There was no bottom in the crevasse. A faint sound could be heard, as if it were the last of them. Presumably they are gone.” 10

The tragic event shook everyone present, and it would shake Amundsen later as well (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 256–257). In such circumstances, they were powerless – both men and dogs. Bjaaland (2011) reported faintly hearing the two fallen dogs howl briefly and realizing that there was absolutely no way to rescue them. Hassel (2011) described the shock of watching two dogs lie down peacefully near his sled, on top of a seemingly solid area of even snow, and then suddenly fall down through the snow, into a 2-foot-wide crevasse, and simply disappear from sight.

How Skalpen must have felt after the loss of his friend Hellik, with whom he had bonded during their early illnesses on the ship and from whom he had been inseparable, is a question worth considering.

After this misfortune, one of Hassel’s dogs, Ester – Hjalmar Fredrik Gjertsen’s dance partner on the ship – also fell through the snow and into a crevasse, but fortunately her harness held, and, dangling above the abyss, she was pulled back up to safety (Hassel 2011). One of Stubberud’s dogs, as well, fell into a crack that the men unknowingly came upon elsewhere, but, also fortunately, the dog was pulled up in time (Johansen Expedition Diary).

Given the danger and approaching darkness, the party felt it best to camp at 3:30 p.m. on that disastrous day (Bjaaland 2011).

As if this were not enough, more trouble followed. By April 7, the party had successfully deposited the seal meat and provision boxes at the first depot at 80° South and had turned around and headed back for home on April 8. Johansen borrowed one of Wisting’s dogs – Hans – to pull on his team. Grim was “completely of no use,” he wrote in his diary, as the dog could not keep up with the sled and came under it instead; Cook (spelled “Kock” by Johansen) also was “useless,” as he had a bad leg. 11 Cook, according to Hassel (2011), had been bitten in the foot. Johansen, therefore, let the two dogs go loose so they could follow his sled. Cook (Kock) limped behind at first but then laid down in his tracks to lick his injured leg. Johansen saw that Cook had stayed behind to heal himself, but Johansen did not wait – he kept on going. The Polar explorer was occupied with the driving – he was the last sled in the caravan, and he had a time goal to meet. Johansen hoped that the dog would follow, even if he lagged behind, the way Lasse had followed his leader, Amundsen, and had come to camp in the evening during the second depot tour, after a day of being gone. When Cook had not shown up yet later that day, Johansen feared that the dog had given up on following him on the path. Grim, in the meanwhile, who had also been loose earlier in the day, drove for a short distance with Bjaaland, who had asked to hitch him on his team. Bjaaland soon regretted this, however, as Grim became tangled up under his sled. Bjaaland let him loose again, and Johansen found Grim lying in the snow on the way to the next camp, as he drove behind the others. He took Grim on his own sled and gave the restless dog a ride the rest of the way, as he “dared not risk letting it go loose [only] to lose it as [I lost] Kock,” wrote Johansen that night at camp, adding: “Maybe I’ll see the latter [Kock] tomorrow again.” 12

Bjaaland (2011) wrote about the two dogs that day as well, although not as hopefully as Johansen had. Instead, Bjaaland commiserated with the severely bitten Cook who had been left behind and prophesized that the dog would probably expire from the freezing cold unless he was able to walk back to the 80° depot and eat some of the seal meat that the men had just stored there.

Cook (Kock) did not show up the following morning, and he was never seen again. Most likely the unfortunate dog froze to death.

The party completed their tour peacefully, changing course so as to avoid the dangerous crevasses they had passed earlier on their way to the depot and marking their way with flags that would help them take the proper route when going on the actual trek to the South Pole after winter. Bjaaland (2011) reported on April 10 that the dogs were healthy, and, as of the 11th, the party was headed home.

“The worst day we have had on these depot tours so far,” Johansen had written in his diary earlier on April 3, the day that the crevasses had claimed his first two dogs, “And the most dangerous one.” 13 His statement would unfortunately prove to be a correct analysis of the entire third depot tour.

Amundsen described how the men and the dogs looked, as they first appeared on the horizon, returning from this successful yet calamitous trip. He watched them coming off the barrier and over the rise, traveling down toward Framheim at such a fast pace that the snow was kicked up all around them (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 256). It must have looked quite like something, with the men and dogs enveloped in a collective halo of snow, the white swirls underscoring their anxiety and their urgency to come home.

The returning dogs were tied up in their tents that night, as a precaution (Hassel 2011), most likely as happy to be home as the men were.

When told of the crevassed area and the unhappy events that had befallen the dogs, Amundsen made a mental note to do everything in his power to avoid this route on their way south after winter. He seemed to empathize with the bad time the dogs had had, writing in his diary about Emil and Hellik’s unfortunate plunge into the snow-covered crevasse and the fact that “there was no question to [try to] save them.” 14 Regarding the dog Cook who had been left behind on the ice trail, for whom Johansen had feelings of guilt, Amundsen felt more disturbed that the dog might eat the provisions laid down at the 80° depot and was later relieved that this had not happened (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 257–258). “Well-fed, thick and round, as it was, I thought we would see it again one day,” he wrote in his diary on April 11. 15 Cook, however, never returned.

As for the crucial third depot tour, completed under the command of Hjalmar Johansen, Amundsen wrote that, “With the exception of the loss of these animals,” all had been a complete success. 16

Dogs and Puppies at Framheim

The same summary statement can be made about Amundsen’s convalescent stay at Framheim, for, during the duration that the third depot tour party was away, Amundsen had been productive, but there were several losses among the canine community that had been sustained at home camp, as well.

On the productive side, Amundsen and the cook/handyman Adolf Lindstrøm had completed the instruments and housing for the new meteorological station; they had fenced in the meat tent with barbed wire so as to prevent any dogs from breaking into it, although it was unlikely that many dogs would do so, given all the seals lying about; and they had barricaded the southeast wall of their house in order to prevent the dogs from climbing onto the roof. As of April 1, Amundsen was surrounded by peace and calm at Framheim (Amundsen Expedition Diary).

The peace, quiet, and time away from his men also allowed Amundsen to concentrate on healing his rectal sore, which was a full-time job in and of itself and, which Johansen observed shortly after returning, on April 12, was still bothering the boss (Johansen Expedition Diary).

During his time home alone and missing in action from the third depot tour, Amundsen had also regaled his diary with entertaining stories about the – in his most estimable view – hilarious, prolific, and versatile Lindstrøm, whose wit and humor delighted the expedition commander to no end. Lindstrøm, perhaps, was to Amundsen what Falstaff was to Prince Hal. He read out loud poems attributed to an anonymous female lover/admirer of the Polar cook, for whom he used coded names, which he now also bestowed upon one of the puppies. “Our smallest puppy – a little lady – he calls miss f.f.,” wrote Amundsen of Lindstrøm’s naming one of the puppies, adding that the pseudonym given was “after the poem’s author. She always haunts in his head.” 17 The “little lady” in question, described by Amundsen as the “smallest puppy,” must have been Lucy’s daughter, the last puppy to be born on the ship. Her mother Lucy (also spelled Lussi) was the only mother who had been allowed to keep a daughter on the Fram. Lucy’s puppy had been born to her on December 28, 1910, as the Fram was nearing Antarctica. Several months later, the female puppy and her mother would be two females who were very much on Amundsen’s mind. On April 30, 1911, Lucy (Lussi) and her daughter disappeared from camp at Framheim. Amundsen tracked their disappearance and happily wrote of their reappearance in his diary a couple of days later: “‘Lussi’ and her 5 month old puppy ‘Miss A.A.’ came again tonight. They had been missing for 2 days. It looked as though they came from the shore. They were hungry.” 18 Although she was the one female born on the Fram who had been allowed to live, evidently this last puppy to be born on the ship had not yet been given a proper name by Amundsen. It seems that he, possibly inspired by Lindstrøm, had used a coded name in referring to her as “Miss A.A.” – just as Lindstrøm had referred to her as “miss f.f.” The name of this female puppy, most likely, was Lussi (also spelled Lucy) as well, named for her mother, and kept as a companion at Framheim. This little Lussi (Lucy) was destined to play a big role in Arctic history – as shall be seen later. (Although the dog named Lussi who is mentioned by the men in later events following the return from Antarctica is never identified as Lucy’s daughter who was born on the ship Fram and code-named miss f.f. and Miss A.A. by Lindstrøm and Amundsen, respectively, at Framheim, it is the author’s belief that this dog indeed is Lucy’s daughter. As she was the only female puppy born on the Fram who was kept alive and taken to Antarctica, and as her age fits the timeline of events, and she was recorded to have made an appearance with Lucy as Miss A.A. but not mentioned on any of the snow expeditions, she must be Lucy’s daughter who was probably kept for breeding and who would later factor significantly in the story.)

As for the losses at Framheim, it was shortly before the third depot party had left, on March 24, that Amundsen surmised that the expedition had tragically lost one of their “older puppies” to one of the crevasses surrounding Framheim. Sadly, it was Madeiro, the puppy who had been born to Amundsen’s admirer, the little redhead Maren, in Madeira. Young Madeiro had lost his mother to the sea when she had fallen overboard during the heavy swells of November. “It [Madeiro] has now been missing for several days,” wrote Amundsen, “and was probably on one of its excursions – which it used to enjoy taking – and fell into a crevasse.” 19 The bad luck of the mother had been extended to the son; just as Maren had been lost to her surroundings, drowned in the sea, Madeiro, too, had disappeared in his surroundings, swallowed by the ice. He was survived by his brother Funcho.

A death from illness also occurred just prior to the third depot party’s departure. It happened at camp on March 27, when Jeppe, one of Prestrud’s dogs, “died on the sled.” 20 Amundsen considered him to be the first dog to die at Framheim, not counting those who had died on the sledding tours – he made a very clear distinction about this. Jeppe had constantly been sick and, in comparison to the other dogs, had failed to gain weight, stated Amundsen in his diary entry obituary.

The other two deaths at Framheim both occurred on the same day – April 8, the day that Cook was left behind on the third depot tour. These were additional sad losses. First, Dødsengelen (“The Angel of Death”) was found lying dead among the puppies. He was Bjaaland’s dog who had grasped onto life while deathly ill on the ship. Amundsen recalled how Dødsengelen had been one of the two dogs who had constantly seemed at death’s door but stayed alive. He must have felt some sadness for the loss after all the perseverance and determination the dog had shown to live. Dødsengelen – The Angel of Death – had been patiently nursed on the ship and had improved under the hands of Thorvald Nilsen and Bjaaland, as had Liket (“The Corpse”) been resurrected by Johansen. Likewise, at Framheim, he had been in good condition, gaining weight and appearing to be healthier, although his legs still were weak. Now, The Angel of Death had succumbed to the latter part of his name. After this loss, Amundsen decided to beat to death “one of our youngest puppies,” Sydkorset (“Southern Cross”), who had recently begun to lose his fur and appeared terribly ill; fearing that the young puppy had an infectious disease that might harm the other puppies, Amundsen made the decision to act in a “radical” manner and to “kill” the puppy. 21 Thus, as a preventive measure – although possibly unnecessary – a second sad loss was sustained.

In Amundsen’s eyes, all was good. The house and tents at Framheim were his and his men’s home sweet home on the Great Ice Barrier. Nearly 60 tons of seal meat had been gathered and lay ready to be consumed, so men and dogs could be in top health. The expedition was all set for its march to the South Pole, with clothes and gear and equipment well suited for the coming trek. The dogs were now trained and broken in; they had shown themselves to be extremely capable and had already proven their worth. And, very importantly, the men and dogs had established three depots with more than enough food for the men and the sled dogs to take on this journey. These depots at 80°, 81°, and 82° contained three tons of food to sustain the expedition members on their way to and from the South Pole.

Now they could settle in for a long winter’s rest before the race became heated again.

Dog Chart: The Dogs Who Died on the Third Depot Tour in March–April 1911

Seven men and 36 dogs – with six sleds being pulled by six dogs each – completed the third depot tour from March 31, 1911, to April 11, 1911, transporting over 1 ton of seal meat to the first depot at 80° South. Three of the 36 dogs died – two by falling into a bottomless crevasse and one from being left behind on the ice. These sled dogs were:

Hjalmar Johansen’s Team – Three Deaths

Emil – Died

Hellik – Died

Cook – Died

Skalpen – Survived

Grim – Survived

One other dog – Survived

Helmer Hanssen’s Team

Mylius – Survived

Ring – Survived

Helge – Survived

Three other dogs – Survived

Oscar Wisting’s Team

Hans – Survived

Five other dogs – Survived

Jørgen Stubberud’s Team

Six dogs – Survived

Sverre Hassel’s Team

Ester – Survived

Five other dogs – Survived

Olav Bjaaland’s Team

Six dogs – Survived

Deaths on the Third Depot Tour

Emil – Fell into a bottomless crevasse

Hellik – Fell into a bottomless crevasse

Cook – Was left behind on the ice

The 36 dogs are the sled dogs who fortified the first depot with enough food to sustain the men and dogs throughout the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition’s trek to the South Pole, planned for the spring.

Thirty-three of the 36 dogs who worked on the third depot tour returned alive.

Deaths at Framheim During March 23, 1911, to April 11, 1911

Madeiro – Disappeared, probably fallen into a crevasse, March 24, 1911

Jeppe – Died of illness, while working, March 27, 1911

Dødsengelen (“The Angel of Death”) – Died of weakness or bad health, April 8, 1911

Sydkorset (“Southern Cross”) – Beaten to death, because looked ill, April 8, 1911

Four dogs died at base camp mid-March to mid-April.

With these total seven deaths, the total number of dogs at Framheim on April 11, 1911, was 100 dogs.

107 dogs in Antarctica as of March 22, 1911

4 died at Framheim March 23 – April 11

3 died on the third depot tour March 31 – April 11

= 100 dogs in Antarctica as of April 11, 1911

There were 100 sled dogs at Framheim, in Antarctica, as of April 11, 1911, ready to make the spring trek to the South Pole.

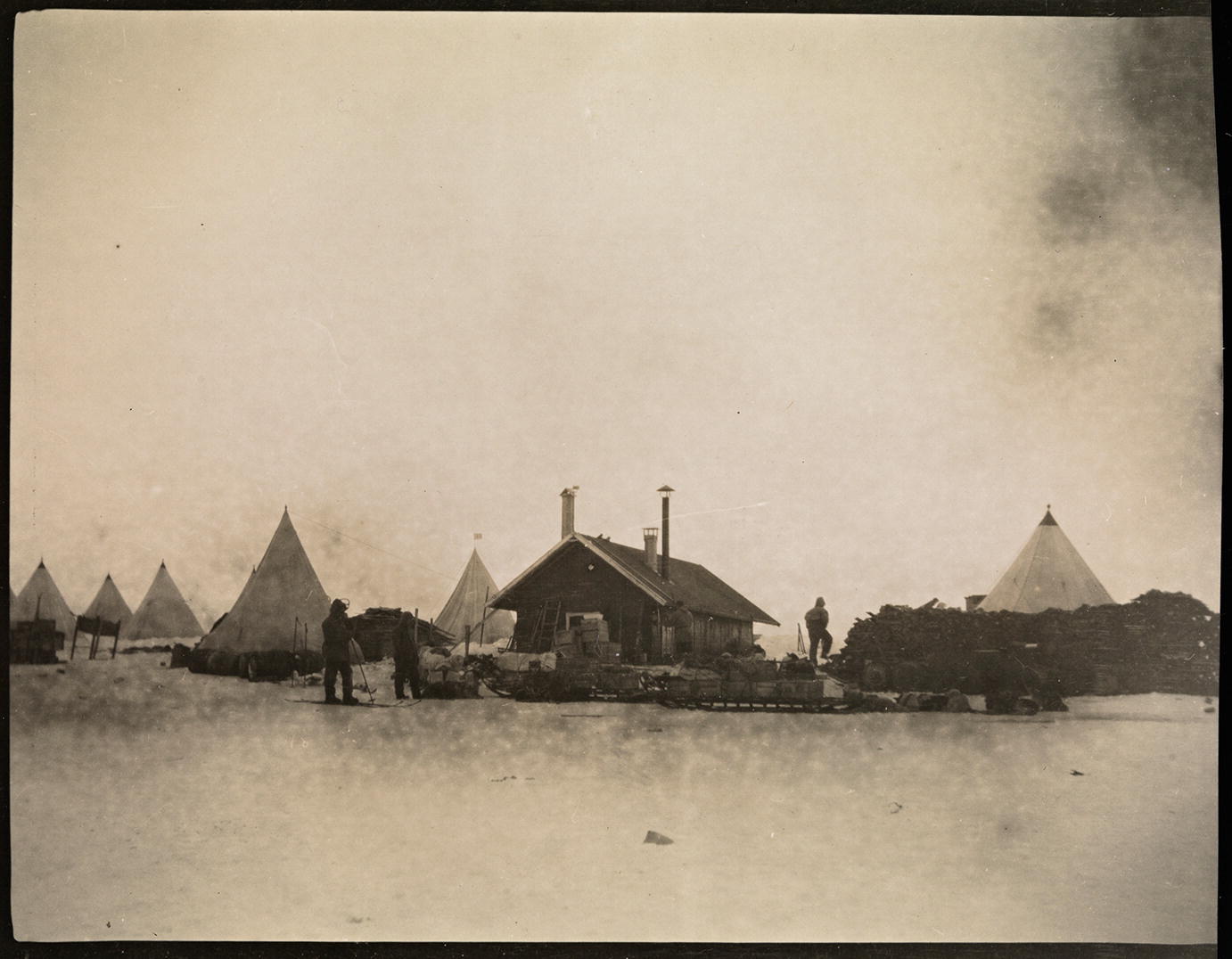

A photo taken during the third depot tour, which was undertaken to supplement the provisions at 80° South and which was commanded by Hjalmar Johansen, from March 31, 1911, to April 11, 1911. The treacherous ice crevasses encountered along the way claimed the lives of some of the sled dogs (Photographer: unidentified/owner: National Library of Norway)

The dogs and puppies at Framheim, congregated around the house, gave Roald Amundsen a true sense of home on the Great Ice Barrier. Nonetheless, casualties among the canine population occurred at the winter base camp as well as on the sledging excursions (Photographer: unidentified/owner: National Library of Norway)

Notes on Original Material and Unpublished Sources

- 1.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 23 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 2.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 23 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 3.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 23 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 4.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 30 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 5.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 31 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 6.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 1 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 7.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 2 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 8.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 3 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 9.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 3 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 10.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 3 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 11.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 8 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 12.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 8 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 13.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, 3 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:2

- 14.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 11 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 15.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 11 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 16.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 11 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 17.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 6 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 18.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 2 May 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 19.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 24 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 20.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 29 March 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 21.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 8 April 1911, NB Ms.4° 1549