Dogged Determination

It was decided in an instant. In one fell swoop, Roald Amundsen upended the globe. The world was turned upside down. He simply switched one pole for the other.

“If I was now to succeed in arousing interest in my undertaking, there was nothing left for me but to try to solve the last great problem – the South Pole,” said Amundsen (1912, vol. 1: 43).

And with that, Amundsen turned the earth on its head.

Amundsen would stake his claim to fame, by going South. He would find his way to glory through the frozen vast land of Antarctica. He would reach not the North but the South Pole. And this time, unlike his previous forays navigating the Northwest Passage or overwintering in the Antarctic Peninsula, he would keep his plan a secret. “If at that juncture I had made my intention public, it would only have given occasion for a lot of newspaper discussion, and possibly have ended in the project being stifled at its birth,” he rationalized (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 45).

It was no matter to him that the world was under the impression he was about to conduct a North Pole Arctic drift expedition; no matter that the famous polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen had lent his equally famous Polar ship the Fram to Amundsen expressly for this North Pole expedition; no matter that Amundsen had already received funding and approval from the Norwegian government for the said scientific expedition to the North Pole; and no matter that scientists and scientific organizations, including the Norwegian Geographical Society and England’s Royal Geographical Society, expected him to go North. He would nonetheless journey to the South Pole.

And immediately upon making this decision, Amundsen determined one thing – one most important thing: He must find dogs! Now! Dogs, believed Amundsen, specifically Greenland dogs, would be the key to his success and would secure his goal. And so, in that September of 1909, he set upon obtaining them.

The very day after making his decision to go to the South Pole, Amundsen was en route to Copenhagen, Denmark, to purchase the best dogs possible for his expedition. He would acquire them from the very reliable and reputable Royal Greenland Trading Company. And he would arrange for the selection and shipment of the dogs personally. For, in this crucial journey, there was no greater advantage nor any more important factor than the speed, ease, and trustworthiness of good Greenland dogs.

The Need for Dogs

The day after my decision was made, therefore, I was on my way to Copenhagen, where the Inspectors for Greenland, Messrs. Daugaard-Jensen and Bentzen, were to be found at that moment. The director of the Royal Greenland Trading Company, Mr. Rydberg, [sic] showed, as before, the most friendly interest in my undertaking, and gave the inspectors a free hand. I then negotiated with these gentlemen, and they undertook to provide 100 of the finest Greenland dogs and to deliver them in Norway in July, 1910.

In actuality, it was only 50 dogs that Amundsen ordered at first. Amundsen had initially requested an amount of 50 sledge dogs from the Greenland Trading Company, with a proportionate number of harnesses, whips, and food for that amount of dogs. Later, Amundsen doubled the quantity to 100. All the dog-related supplies had to be adjusted subsequently for the new amount.

Perhaps it was because of his impulsive decision that he decided to cover himself with twice the number of dogs that he had initially thought he would need, in order to secure his success. Perhaps he wanted to increase his chances for victory in the assault on the South Pole, with an increased amount of dogs.

Strategically, one sees a method in Amundsen’s dog madness – it was a security issue at heart. Amundsen had built in a strategy of redundancy into his system. Like modern-day transportation methods, there was room for one element to fail, as there was a “backup” to it that would immediately replace it upon its malfunction. Therefore, it would seem that Amundsen’s magic number of 100 dogs was meant as that security blanket – a redundant element for each working element that would serve as a “replacement” in the event of the first element’s demise, a trained understudy dog standing in the wings for each active dog. The redundancy was instrumental to his system. And its effectiveness – sometimes brutal – would be seen later during the preparations and the actual march to the South Pole.

Amundsen placed his order of 50, then 100, dogs with the Greenland Trading Company between the dates of September 8, 1909 – the day after the Cook-Peary North Pole discovery news was released, and September 17, 1909 – the date Amundsen’s amended order for 100 dogs appeared as a confirmation in a letter from the company.

Roald Amundsen had a prior history with this trusted resource. The Greenland Trading Company was the only source certified by the Government of Denmark to export dogs as well as clothing and equipment from Greenland. The company worked under the auspices of the Danish government. Amundsen’s close relationship with the director, Carl Ryberg, and the inspector, Jens Daugaard-Jensen, and his history with them (they had provided the dogs for his Northwest Passage expedition) gave him a bit more prestige.

Amundsen made his way post haste to Copenhagen, where the Greenland Trading Company offices were housed and where their large brick warehouse was located near the port. Through this personal visit with the inspectors, meant to drive home the importance and urgency of his requested order, Amundsen emphasized his desire for the absolutely best dogs.

The company in turn was extremely responsive and accommodating, immediately beginning the paperwork necessary for the selection and importation of the best dogs from Greenland to Norway. They proceeded to make all the necessary arrangements to bring the 100 dogs on a ship that would off-load the sled dogs at Kristiansand (known, at that time, as Christianssand) in southern Norway, where they would be kept on Flekkerøy (then known as Flekkerö) Island, off the mainland. After that, the dogs would be boarded onto Amundsen’s Polar ship, the Fram, for the “North Pole” expedition.

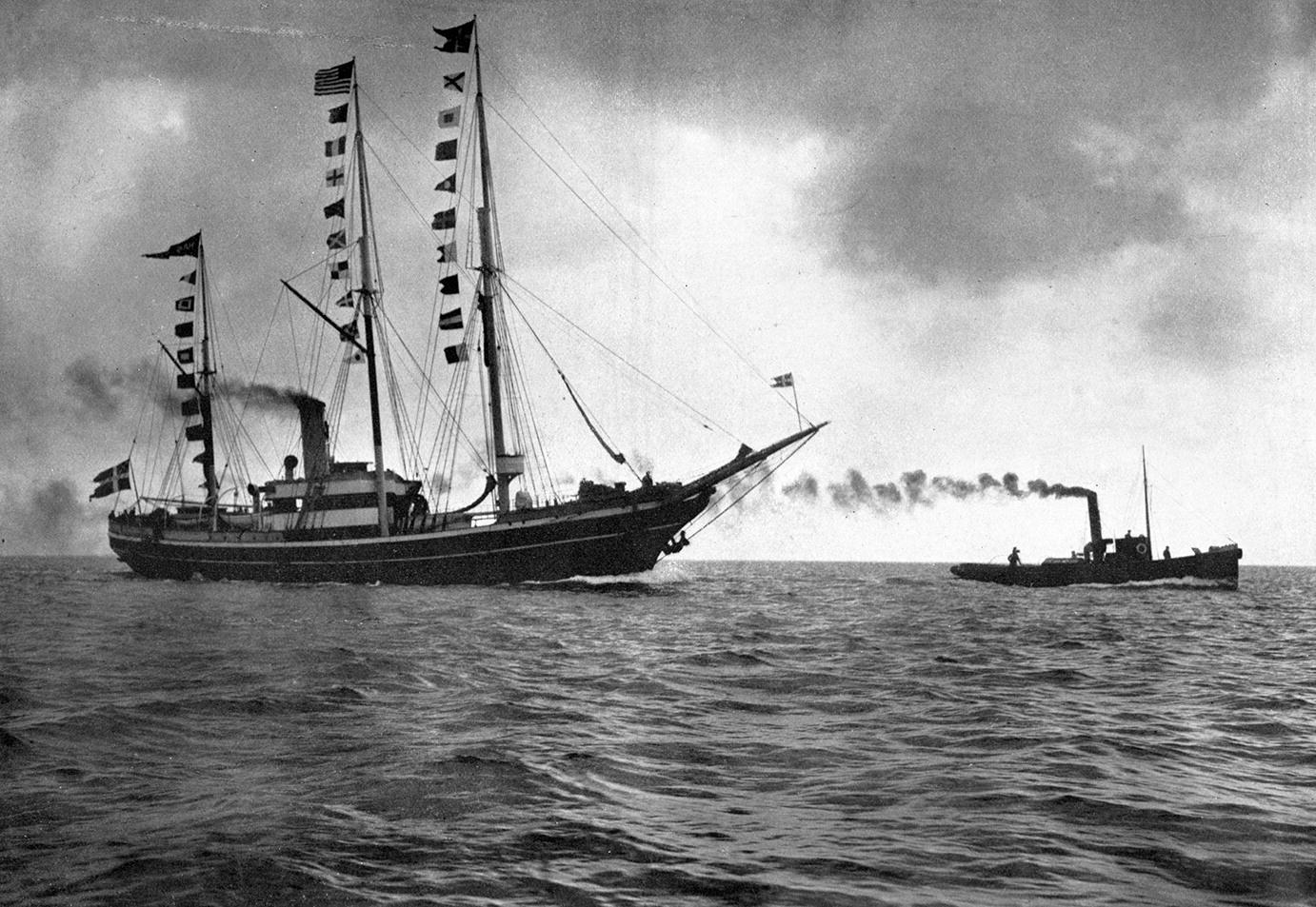

Amundsen’s personal visit to the Greenland Trading Company coincided with another illustrious explorer’s visit. Dr. Frederick Cook – one of the two contenders for the North Pole discovery and the reason why Amundsen had secretly changed his plans from the North to the South Pole – had just arrived in Copenhagen from his North Pole trip, having traveled during late August and early September with none other than Inspector Jens Daugaard-Jensen himself, on board the S/S Hans Egede – the very same ship that would later bring the 100 dogs from Greenland to Norway and deliver them into the hands of Amundsen.

The Greenland Letters: Sex, Secrets, and Pemmican

Roald Amundsen returned to Norway from his urgent trip to Copenhagen with renewed vigor and determination. Now began an intensive negotiation between him and the Greenland Trading Company regarding the purchase of the dogs and provisions for the “North Pole” expedition. To the Greenland Trading Company and the rest of the world, this was still a planned excursion to the North Pole. The true destination of the Norwegian expedition – the South Pole – was known only to Amundsen and his brother Leon at this time. It was a fine balancing act, then, for Amundsen to make the necessary preparations for a real expedition under the guise of an imaginary one. The permissions he had to obtain, the restrictions with which he had to comply, and the descriptions, ages, sexes, costs, caring for, and perceived value of the dogs were all spelled out in a series of letters of correspondence between him and the Greenland authorities (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence).

In a letter from the Greenland Trading Company’s Inspector Jens Daugaard-Jensen, Director in Greenland, to Captain Roald Amundsen, dated September 14, 1909, 1 Daugaard-Jensen assured the captain that he had begun all preparations to obtain the items needed from Greenland, “as I beg you to believe that I will do everything which is in my power to do this as best as I can.” The good inspector was very polite. He corresponded in small, neat, and consistent handwriting that was as near to typewritten lettering as one could get employing free-hand.

The long letter went on to summarize information about sleeping bags and bird skins, skins for boots and fur lining, and dried fish. “Everything is going to be furnished in Greenland before the Hans Egede’s second scheduled trip next year,” he said, referring to the ship that would bring the dogs to Norway. “We will be finished in mid-June of next year. The only thing that is bothering me is the dogs’ food. Ten tons of lodde [a small fish] for their food is such a big order, it will be difficult to get that much, as this fish normally comes in around the first of June. It is also a very short time to get it dried.” But he went on to say that he would commission another inspector in South Greenland to try to obtain this fish, as they had two fishnets and would make every attempt to catch that large amount; however, this would, of course, mean that the price would be a little bit higher for the fish – 6 ore per kilo (1 krone = 100 ore) for this dried lodde. As he was concerned that the fish would arrive so late, and there may not be enough time to dry it before loading, would it be possible instead to prepare it as a paste using fat, he asked. “If so, this must be done during the winter, so please decide if we should continue with this food,” he requested of Amundsen.

Ultimately, Amundsen’s decision must have been in the affirmative, as indeed he did take fish pemmican (dried fish with lard, dried milk, and middlings) and daenge (a fish-and-butter mixture), as well as meat pemmican and dried fish, on the southward expedition – although, in his official book, he named other sources for securing this dog food. One of those sources he named was the expedition agent in Tromsø, “Mr. Fritz Zappfe [sic]” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 1: 56) – Fritz G. Zapffe was a friend of Amundsen.

By now, Roald Amundsen’s brother Leon was serving as Amundsen’s business manager in all things concerning his expeditions. And, as mentioned, he was the only other human being in on the secret regarding the diversion to the South Pole. Therefore, some of the correspondence to the Greenland Trading Company was prepared by Leon on behalf of his brother Roald. These letters were part of volumes and volumes of onion-skin letter copies kept by Leon in bound volumes. The numerous copybooks were all chronologically ordered, notated, and cross-referenced by him. Leon was as meticulous in organizing and documenting his business records as Roald was in planning and executing his expeditions. The handwriting on these letters appears in brown ink on the ultrathin paper, with a “Roald Amundsen” signature stamp at the bottom.

In a letter from Roald Amundsen sent via Leon to the Greenland Trading Company/Greenland Administration, addressed “To the Inspector for North Greenland Mr. Jens Daugaard-Jensen” and to “Greenland Department, Copenhagen”, dated September 14, 1909, 2 Roald/Leon inquired, “As you have been so willing to find Eskimo dogs and different equipment from Greenland for my next polar expedition, I need to inquire in which way I may make the entire payment. If you will give me the approximate amount, I can deposit the payment in Copenhagen.” Because acquiring “Eskimohunde … from Greenland” was the first order of business – the priority item on Amundsen’s action plan, Leon now went to work making all the payment arrangements.

On the same day, Amundsen also submitted his official request to the government of Norway for permission to purchase and import Greenland dogs for what he called the “Fram” expedition. In a letter written from him through Leon, addressed to “Landbruksdepartement” – the Norwegian Agricultural Department – and dated September 14, 1909, 3 Amundsen asked the “Department’s permission to import Eskimo dogs from Greenland. They are going to go with my ship to my next Polar Expedition. I believe that this importing of the Dogs will require that they be shipped twice – from Greenland to Norway.” It is not clear if Amundsen thought the dogs would have to come in two shipments or if this was due to their large number, but all the dogs came on one ship, as will be seen later.

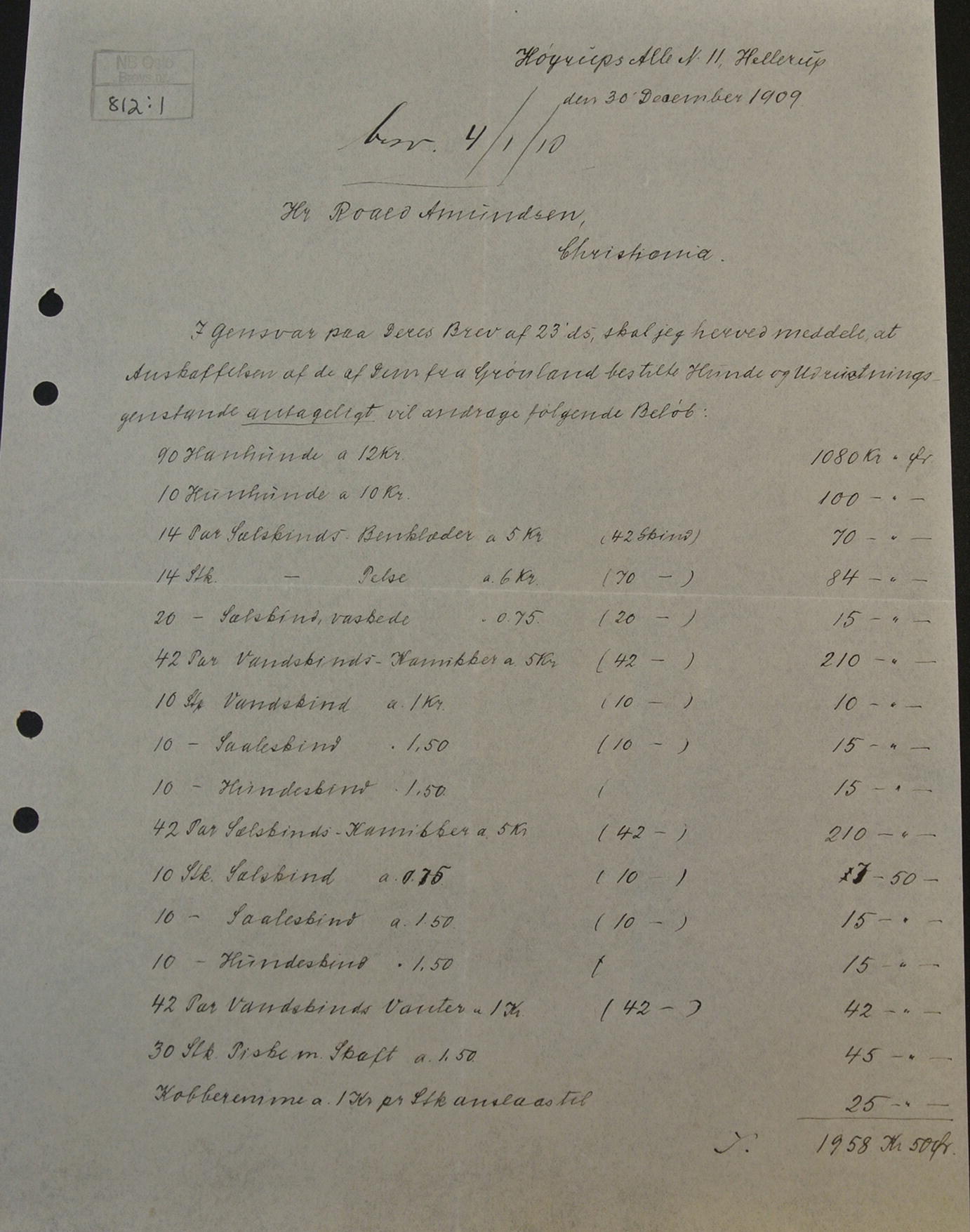

The final tally and cost of the 100 dogs to be purchased from the Greenland Trading Company came in a letter handwritten from Jens Daugaard-Jensen to Roald Amundsen, dated September 17, 1909, 4 and sent from Denmark from “Hoyrcips Alle N. 11. Hellerup.” The letter included pages formatted in a ledger-like manner, with columns of itemized material and their calculated costs neatly listed.

The list of equipment begins on page three of the letter, with the dogs featured as the headliner. Number one of the 16 items listed, with their itemized and total costs, reads “1) 90 Hunde a 12 Kr og 10 a 10 Kr – 1,180 Kr,” meaning “90 Dogs at 12 Kroner each, and 10 dogs at 10 Kroner each, equaling a total of 1,180 Kroner.” The difference between the 12-kroner dogs and the 10-kroner dogs is not apparent at this time – what was it that made one dog cost more than another? The grand total for the order, at any rate, is given as 2,145 kroner – meaning that more than half the cost of the provisions was for the dogs alone.

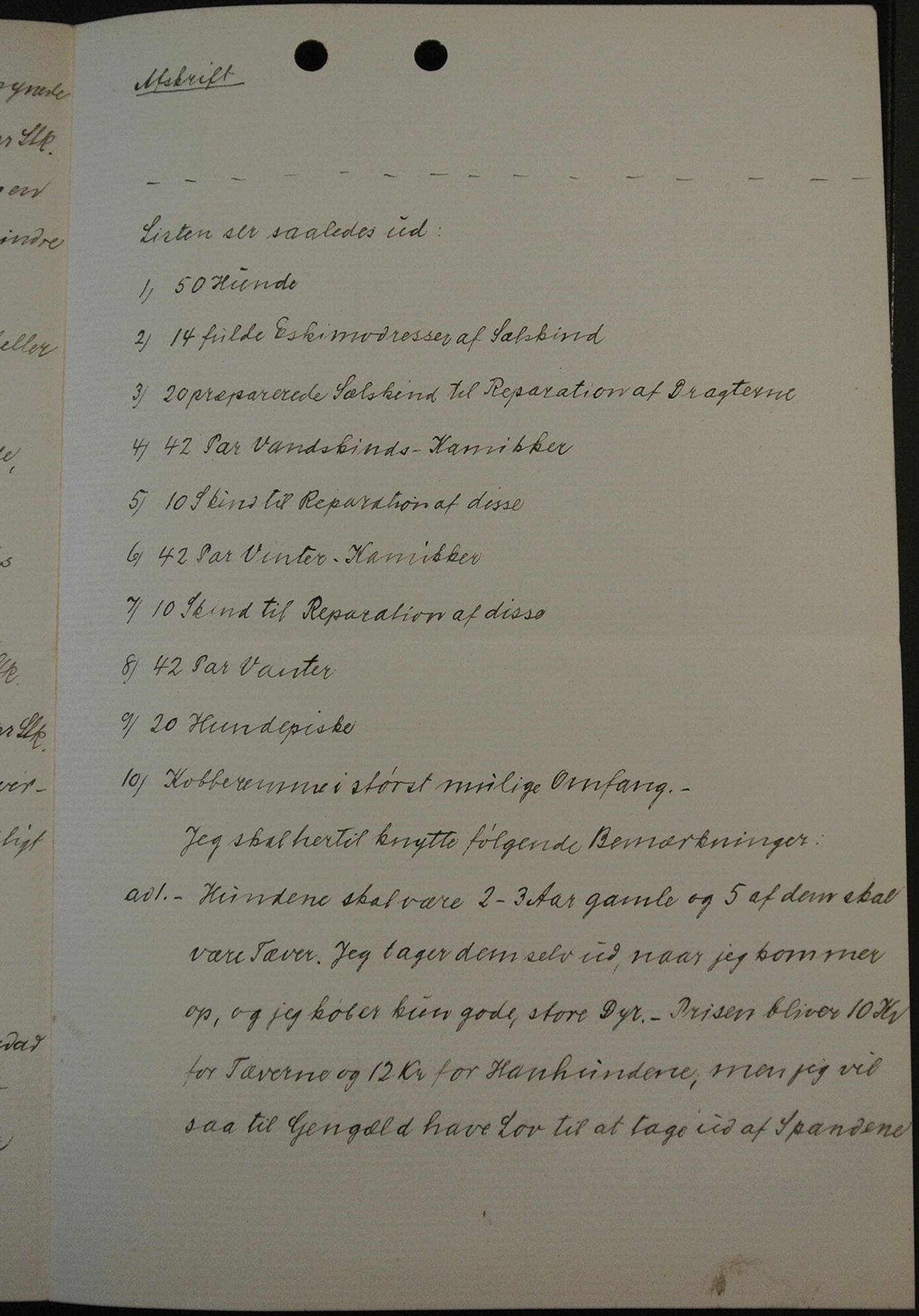

A separate sheet in the letter features a different list – this one shows ten items with no costs. The first item listed is “1) 50 Hunde.” So, this must have been a previous list for “50 dogs” that Amundsen had originally ordered, and now it was copied here with the letter reflecting the updated, doubled amount. This earlier list also contains text underneath specifying that “All dogs will be 2 to 3 years of age, and 5 of them will be female.” Daugaard-Jensen added: “I will pick them up myself when I come there [to Greenland] and I will buy only good, big animals. The price for the dogs is 10 Kroner for each female and 12 Kroner for each male. But I promise I will take only the dogs that are the best.”

So now we know why there was a difference of cost for the dogs – it was a matter of their sex. The female, evidently, was perceived to be worth a lesser value than the male. Was it their size? Their disposition? Perhaps the men believed the females were weaker – but it had been shown that female huskies were many times selected as the lead dogs by the Inuit and that they were quick and intelligent and loyal, just as the males were; also, with females, one is more likely to gain more dogs, as one dog would beget another, so to speak, so one might think that the female would actually be more valuable. However, this was not the case here with the Greenland Trading Company. Despite this arbitrary value, the females, as shall be seen, would later prove their worth during Amundsen’s Antarctic journey.

In regard to the number of female dogs vs. male dogs, it would seem that the good inspector targeted a certain percentage of the dogs to be female – five of the 50 that were originally ordered, and 10 of the 100 that were confirmed ordered. One would deduce, then, that 10% was their target, resulting in 10 females and 90 males being ordered as the finalized purchase.

The location in Greenland from which to obtain the dogs, too, was strategized by the inspector. “I will announce in Egedesminde, Godhavn, and Jakobshavn Districts that you need dogs in those three districts,” continued Daugaard-Jensen on another page of the letter, assuring Amundsen that he would obtain dogs from those best three districts that make up the west coast of Greenland – known today by their Greenlandic names as Aasiaat, Qeqertarsuaq, and Ilulissat. He also assured the explorer that he would put out as wide a net as possible to attract the best dogs from those harbor/coastal areas. (Godhavn at Disko Island is where Amundsen had met representatives from the Greenland Trading Company before, in 1903, to collect his additional dogs from Greenland on his way to the Northwest Passage.)

The letter includes lists of other suggested items that would be needed. Dog whips are listed as number “9” at a quantity of 20 with the original order of 50 dogs and then increased to 30 with the doubled order of 100 dogs. In this latter list, the whips are cost-itemized at 1.50 kroner each, totaling 45 kroner. “Eskimo” clothes and 10 dogskins at 1.5 kroner each, equaling 15 kroner, are listed twice as numbers “5” and “7”.

“Do you need the dog food?” asked Daugaard-Jensen in the letter. This was one of the final questions he needed answered: whether Amundsen would order the dogs’ food from him or not. Dog food does not appear on the final-order confirmation from the Greenland Trading Company but was indeed provided by several sources, as reported by Amundsen.

Curiously in the letter, prior to the lists on page three, the inspector also mentions Robert Peary – the other contender for the North Pole discovery – and the second reason for Amundsen’s switch to the South Pole. It seems that Amundsen could not get away from the Cook-Peary news.

Answering the letter of the 14th of this month, where you requested permission to import from Greenland Eskimo dogs meant for your forthcoming polar expedition. Yes, you may, on these conditions: 1) There must be a document from the Greenland Authorities certifying that the dogs are healthy and that they do not originate from a district in Greenland where rabies or other serious dog diseases are present; 2) The dogs must be looked after by a Norwegian veterinarian and be declared free of diseases. This document of certification must be shown as identification to customs or police when the animals arrive.

We must surmise here that Amundsen had Oscar Wisting, his crewmember whom he had sent to veterinary classes, assist in providing some veterinary services and in maintaining the health of the dogs at Flekkerøy Island and Kristiansand prior to the expedition’s departure south.

Three days after the Department for Agriculture’s letter was sent, the Director of Administration for the Colonies in Greenland made the entire Amundsen North Pole expedition purchase official. Carl Ryberg, the Director for the Greenland Trading Company, sent two letters from Copenhagen to Roald Amundsen, both dated September 20, 1909.

The first letter from Ryberg was handwritten on official director’s letterhead but seems to be a private correspondence to his friend Amundsen. 6 In it he mainly talks about a strange incident that happened to him that day, wherein he received a telegram sent from “Christiania” (Oslo) on the same day, saying, “Please endeavor to get Knud Rasmussen [the Danish-Inuit Arctic explorer] home soonest possible. Signed, Cook.” Ryberg goes on at length to describe how odd it was to receive this telegram which seemed to be 1 year old. Then, after this informal chitchat with Amundsen, on the back of the letter, at the very end, Ryberg touches upon the business at hand, giving Amundsen an informal heads-up that Amundsen’s request for the dogs from Greenland most likely would be granted. “It seems that the answer will be yes,” he says. He then goes back to the Cook-Rasmussen gossip: “I will ask you to try to find out what happened when you come to Christianssand,” referring to the Kristiansand location in Norway where the dogs ultimately would be brought for boarding onto the Fram. (Interestingly, 10 years later, Knud Rasmussen would organize logistics and depots for Amundsen’s Maud expedition in the Arctic [Rasmussen Personal Papers], writing to him in June 1919 about supplies, provisions, and caches for the attempted Polar drift, on letterhead from Rasmussen’s “Cape York Station Thule” 7 ).

This letter from the Administration of Greenland is in answer to your writing of the 14th of this month. There is no problem with the dogs you have ordered. In response to a question from the Inspector of North Greenland [Jens Daugaard-Jensen] who has ordered the Greenland dogs, the dogs should be shipped from Greenland with the S/S ‘Hans Egede’ 2nd travel next year, to be put on shore in the South of Norway, most likely close to Christianssand.

Thus, this letter made official what Ryberg had communicated to his friend Amundsen unofficially in the previous letter: (1) that the request for dogs had been approved, (2) that they would arrive on the Hans Egede during the second trip scheduled for the following year between Greenland and Norway (June–July), and (3) that the dogs would be brought on shore in Norway in the southern part, probably in Kristiansand.

Now Amundsen set about fulfilling the Norwegian government’s requirements regarding showing proof of the dogs’ health, as stipulated by the Department for Agriculture in their September 17 letter. Roald/Leon immediately corresponded with the Greenland Trading Company requesting that it provide a health certificate for the dogs. A reply letter from the company to Roald Amundsen, dated September 22, 1909, 9 assured him that there would indeed be a declaration of the dogs’ health accompanying the dogs when they arrived and that the clearance would be obtained from Denmark. The letter was signed with an accommodating and congenial “At Your Service.”

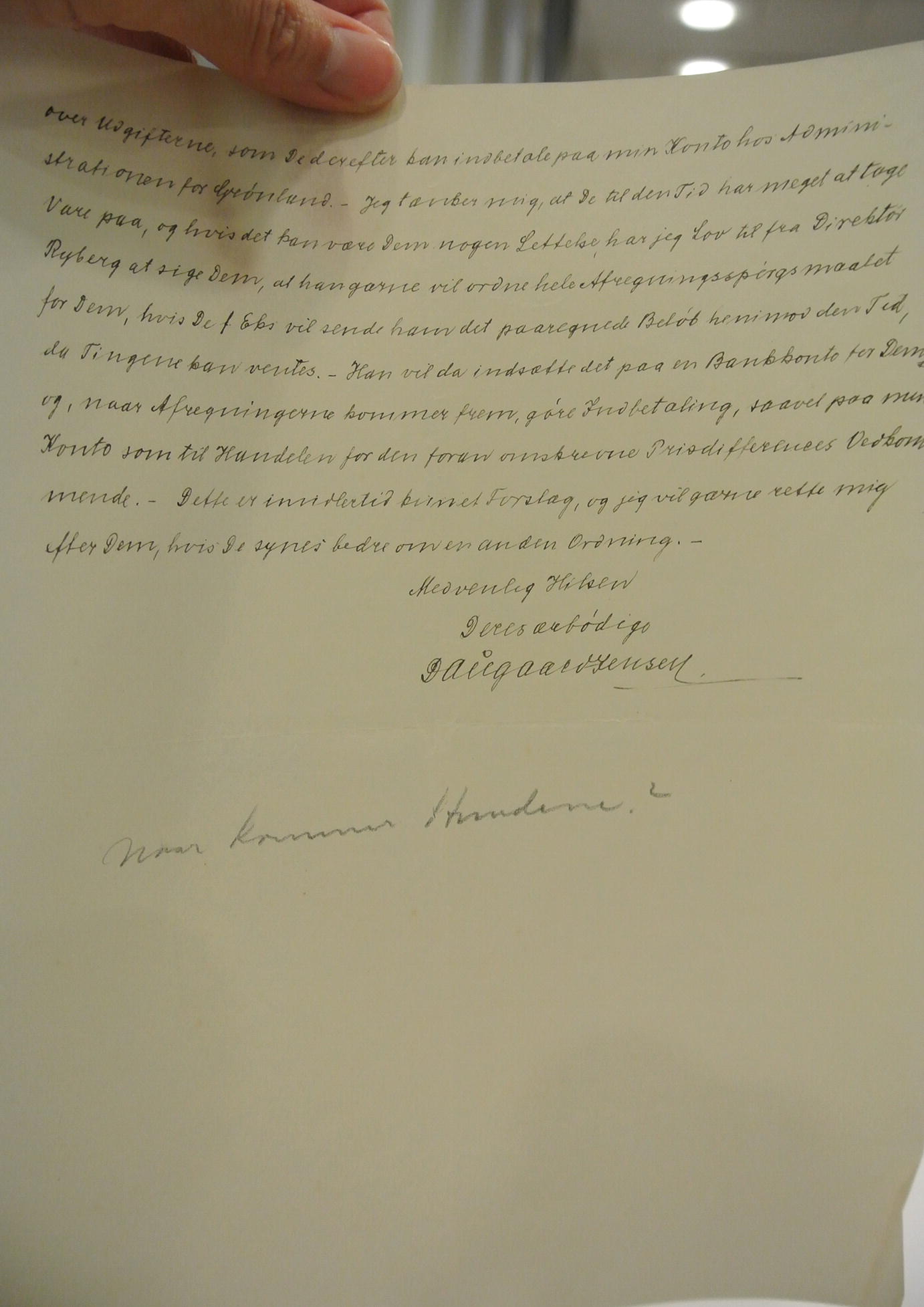

Amundsen was nonetheless impatient. His most urgent need was to secure the dogs, and this required a guarantee of payment which Leon was working to obtain. Therefore, Roald, through Leon, sent a plea to Daugaard-Jensen on December 23, 1909, 10 requesting yet again the final costs for the dogs and equipment. He finally received an answer. The official letter of confirmation regarding the costs and purchase of the dogs came from Daugaard-Jensen on December 30, 1909. 11 The inspector replied to Amundsen: “I have now ordered from Greenland the best dogs – 90 male dogs at 12 kroner each, and 10 female dogs at 10 kroner each. I have also ordered dog skins [used for blankets and clothing].” Within the letter was inserted a confirmed listing of all items purchased. At the top of that listing is written “90 Hanhunde a 12 Kr – 1080 Kr” and “10 Hunhunde a 10 Kr – 100 Kr”. Also listed are 30 whips, but no harnesses or pemmican. This letter thus confirmed the final cost and purchase of the sled dogs and their perceived values – values that both the male and female dogs would exceed in terms of outstanding performance in Antarctica, as shall be seen.

Very interestingly, and quite tellingly, on the last page of this same letter, at the very bottom, underneath Daugaard-Jensen’s distinctive signature with added flourish, was a question written by Amundsen, presumably to Leon, scrawled in urgent, large handwriting across the full width of the page: “Naar kommer Hundene?” – “When are the dogs coming?” The handwritten sentence seems to scream impatience from Amundsen, most likely owing to the high priority that the strategic explorer had placed on the dogs; for by this time, at the end of the year 1909, Amundsen was quite desperate to know when his 100 good Greenland dogs would arrive – the dogs who would take him to the South Pole and to the place in history that he so fervently believed he deserved.

A Fortress to House the Sled Dogs

The answer to the big question, as to when the dogs would arrive, came to Amundsen at the beginning of the New Year.

In a letter from Jens Daugaard-Jensen dated January 9, 1910, 12 the good inspector informed Amundsen that he believed the dogs could be delivered around the 10th of July of that year, but he urged Amundsen to make all preparations official and admonished him to be more precise in all his arrangements, as well as to painstakingly spell out where everything was to be delivered.

Telling Amundsen to be precise was like telling a dog to wag his tail; Amundsen was nothing if not constantly calculating and always specific. Perhaps, however, the big secret he was keeping caused Amundsen to now sound much more vague than usual. Perhaps withholding the true nature of the expedition kept the great explorer from being as detailed and as forthright about his plans as he normally would have been.

“I know you have spoken to the Director regarding having everything put ashore in Christianssand,” stated Daugaard-Jensen in his letter, referring to the plan to off-load the dogs and supplies from Greenland at Kristiansand. “I’m not sure if everything is sorted out officially yet?” The inspector went on to request payment and a bank guarantee in his formal, business-like tone, and asked where exactly the dogs would be dropped off. “Please be specific about location and time.”

The next series of five letters during late January and early February 13 between Amundsen and Daugaard-Jensen was a bit of a comedy of errors, possibly due to the timing of mail delivery, as by now the inspector was in “Hoyrupo, Greenland.” In these letters, Roald/Leon Amundsen and Daugaard-Jensen discussed back and forth the dogs’ arriving in Kristiansand, their transport on the second ship being scheduled for the coming summer, the delivery request being made official with the director, and the payment and bank guarantee required, as well as the ever-burning question from Amundsen, the main priority of this entire endeavor: “I would be very pleased if you let me know when the dogs will arrive.”

Two new topics now thrown into the discussion were inquiries by the inspector if Amundsen would be willing to speak with an Inuit journalist and if he liked the goggles that Dr. Cook used.

Meanwhile, it fell to Amundsen to arrange the precise location where the 100 dogs would be off-loaded from the Hans Egede upon arrival in Norway from Greenland. As noted, the Greenland inspector had requested that Amundsen make this arrangement well before the time of shipping. The Norwegian government had already given Amundsen permission to bring the dogs on shore at Kristiansand. But where would there be an appropriate and large enough space to accommodate 100 vibrant, free-spirited Polar dogs who had just arrived from a confined and turbulent 3-week sea voyage?

The answer was a fortress, specifically, Fredriksholm, the seventeenth-century battalion which stood in magnificent ruins on the beautiful island of Flekkerøy, located in the islet near Kristiansand. It would be a perfect spot.

Although in ruins, the structure was still considered a fort, and so it was necessary to obtain permission from the military. And so, Roald Amundsen, again with Leon’s help, wrote to the Commander of the Harbor of Kristiansand on February 8, 1910, 14 requesting permission to use the old fort to house the dogs upon their arrival. The letter was addressed to “Herr Lodsformann Langfeldt, Christianssand S.” By this time, Amundsen had already made arrangements with the commander for docking the Fram at Kristiansand and now wished to also “inform the Langfjord pilot that the Greenland ship with the Eskimo dogs will be arriving in the middle of July. Of course, all the costs for this arrangement will be in our hands,” he added. “At this time, I ask if we would have the opportunity to use Fredriksholm.” Amundsen was preparing a temporary home for the dogs who would arrive in Norway to accompany him on his expedition.

Meanwhile, the good inspector from Greenland was doing his best to make all the arrangements for bringing the dogs and was being very thorough in foreseeing any and all requirements.

It was confirmed through the subsequent correspondence between Amundsen and Daugaard-Jensen that Amundsen expected the ship bringing the dogs to arrive in mid-July, that the dogs would be put ashore in Kristiansand with the official permission of the Norwegian government, and that Amundsen would be required to cover all the costs involved.

All that was left, then, was to bring the dogs – or was there something else?

The original list from the Greenland Trading Company, showing Roald Amundsen’s initial order of 50 Greenland dogs, which was included in the September 17, 1909, letter from Inspector Jens Daugaard-Jensen. (National Library of Norway)

The final list from the Greenland Trading Company, reflecting the gender and cost of the 100 sled dogs whom Roald Amundsen purchased from Greenland, as presented in the December 30, 1909, letter from Jens Daugaard-Jensen. (National Library of Norway)

The S/S Hans Egede (left), festooned with flags, enters the Copenhagen harbor on September 4, 1909, with Dr. Frederick Cook on board, returning from his journey to the Arctic, following his claim to having reached the North Pole. Roald Amundsen, coincidentally, was in Copenhagen around this same time, purchasing Greenland dogs for what would be his South Pole expedition. Nearly a year later, this same ship the Hans Egede would bring the 100 sled dogs from Greenland to Norway and into the hands of Roald Amundsen. (Photographer: unknown; Owner: M/S Maritime Museum of Denmark)

“When are the dogs coming?” asks an impatient Roald Amundsen in a note written on the December 30, 1909, letter from Jens Daugaard-Jensen. (National Library of Norway)

Notes on Unpublished Sources

- 1.

J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 14 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 2.

R. Amundsen to J. Daugaard-Jensen, 14 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:3:4

- 3.

R. Amundsen to Landbruksdepartement [Norwegian Agricultural Department], 14 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:3:4

- 4.

J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 17 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 5.

Landbruksdepartement [Norwegian Agricultural Department] to R. Amundsen, 17 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 6.

C. Ryberg to R. Amundsen, handwritten letter, 20 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 7.

K. Rasmussen to R. Amundsen, 13 June 1919, Knud Rasmussen Personal Papers, File 12 Box 1, Henry Larsen Collection, Leonard G. McCann Archives, Vancouver Maritime Museum, Vancouver, B.C. (Translated by Espen Ytreberg)

- 8.

C. Ryberg to R. Amundsen, typewritten letter, 20 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 9.

J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 22 September 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 10.

R. Amundsen to J. Daugaard-Jensen, 23 December 1909, NB Brevs. 812:3:4

- 11.

J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 30 December 1909, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 12.

Daugaard-Jensen to Amundsen, 9 January 1910, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 13.

R. Amundsen to J. Daugaard-Jensen, 14 January 1910, NB Brevs. 812:3:4; J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 19 January 1910, NB Brevs. 812:1; R. Amundsen to J. Daugaard-Jensen, 21 January 1910, NB Brevs. 812:3:4; R. Amundsen to J. Daugaard-Jensen, 7 February 1910, NB Brevs. 812:3:4; and J. Daugaard-Jensen to R. Amundsen, 9 February 1910; NB Brevs. 812:1

- 14.

R. Amundsen to Lodsformann Langfeldt, Christianssand [Kristiansand Harbor Commander], 8 February 1910, NB Brevs. 812:3:4