The Eastern Party’s Progress

While Roald Amundsen and his South Pole party had been maneuvering their way across the Polar plateau, trekking through the mountain passes, and reaching the South Pole – as well as dancing with the Devil on his glacier and ballroom and filleting their trusty canine comrades at the Butcher’s Shop – the Eastern expedition party of 3 men and 17 dogs had been efficiently and pleasantly making its way to King Edward VII Land and back.

When last we saw them, Hjalmar Johansen, Kristian Prestrud, and Jørgen Stubberud, along with their two teams of sled dogs, had left the first depot at 80° South on November 13, 1911, fully loaded with food and equipment – and an extra sled dog. They had picked up Peary – the dog left behind by the South Pole party in October – on November 11, the day before they had reached this depot. Peary had been found taking shelter near the two snow huts that had been built earlier during the false start of September 1911.

The Eastern party had embarked on a journey projected for 5 weeks back on November 8, leaving Framheim and cook Adolf Lindstrøm behind, along with the remaining dogs and puppies, and setting a trail for their expedition. On each of their 2 sledges were 600 pounds of provisions, instruments, medical supplies, and equipment. The party was provisioned with seal meat and three cases of dog pemmican for the dogs. And, in the course of their travel, they had found their dogs to be excellent workers and company.

In reaching this first depot at 80° on November 12, Hjalmar Johansen, in his diary, noted that the men had found a surprisingly large amount of seal meat still stored in the depot, which they had thought the South Pole party would have fed to the 52 dogs who had embarked on the South Pole trek (Johansen Expedition Diary a). “Presumably the dogs have been so underfed, that they could not handle much,” he concluded. 1 He, Prestrud, and Stubberud, on the other hand, made sure to feed their 17 dogs to the fill and to take enough food along with them for their journey – both pemmican and seal meat; they also killed seals along the way, during the first portion of their journey, in order to further supplement the food for both the men and dogs.

As the party members headed east from depot 80°, taking it upon themselves to discover new land on their way northeast to King Edward VII Land, which Amundsen had assigned to them to explore, the 3 men and 17 animals seemed a cohesive, companionable, cooperative group – sans stress, sans drama (Amundsen 1912; Johansen Expedition Diary a).

The eight dogs pulling Johansen’s sledge were:

Vulcanus

Snuppesen

Brun (“Brown”)

Dæljen

Liket (“The Corpse”)

Camilla (also Kamilla)

Graaen (also Gråen)

Smaaen, also called Lillegut (“The Small One” or “Little Boy”)

Finn (also Fin, who had previously fallen into a crevasse)

Kamillo (Camilla’s son)

[Maxim] Gorki

Pus (“Kitty”)

Funcho (also Funko and Funco, who was Maren’s and Fix’s son)

Storm (Else’s son born on the ship)

Skøiern

Mons (whom Sverre Hassel had traded out of his team due to the effects of the premature start)

Peary (from the South Pole party, picked up near 80° S depot on November 11, 1911)

The time between their departure from the depot on November 13 and their return from King Edward VII Land on December 16 was spent exploring the new land and collecting samples for scientific study. The canine contingent on this important scientific expedition worked hard and proved their worth (Amundsen 1912; Johansen Expedition Diary a; Johansen Expedition Diary b). Though the conditions were challenging and the work demanding, no dogs were harmed on this journey.

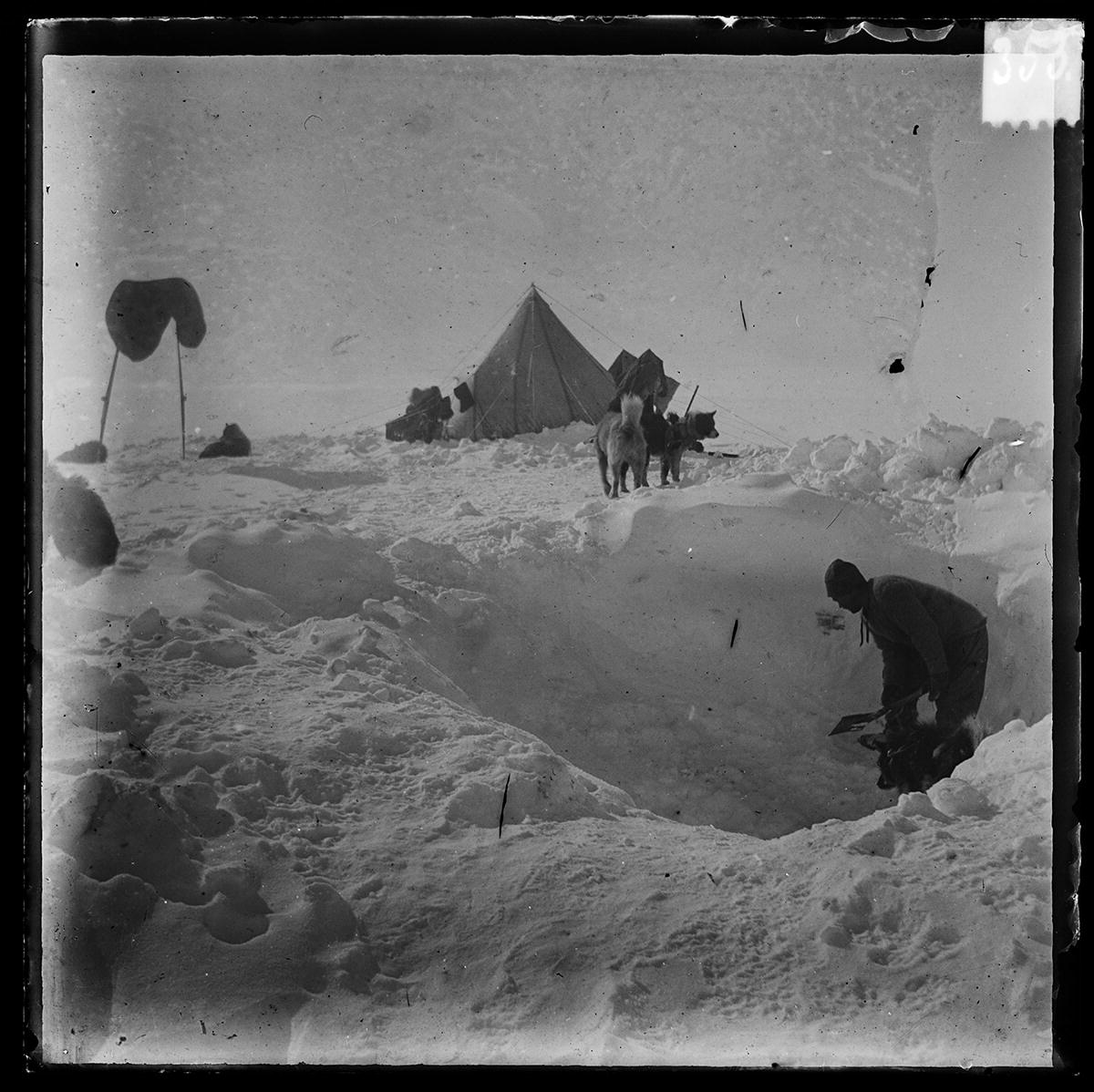

Johansen’s diary is full of anecdotes regarding the serious work, smooth performance, and various humorous antics of the dogs during this mission of exploration (Johansen Expedition Diary a; Johansen Expedition Diary b). Though easier than the South Pole trek, this Eastern expedition still had its own risks and arduous circumstances. The dogs climbed the barrier, pulled the men to areas where they could survey the land, and battled blizzards that effectively buried them underneath the snow. A close call with a crevasse on November 28, during which two dogs from Stubberud’s team were left hanging head-down in an open abyss, ended with the dogs being pulled up safely – both unharmed, but very shaken. The incident brought to Johansen’s mind the traumatic disappearance of his two dogs Hellik and Emil, whom he had lost to a crevasse during the third depot trip in the autumn, and for whom he still pined. While the dogs set themselves to do intense work, they also found time to express themselves in their own individual personas. Johansen wrote of how Camilla, during the austere camping conditions on November 19, created an unusually comfortable sleeping environment for herself and for her teammate Gråen, tearing apart a pillow case that Johansen had kept that was filled with the organic insulating material sennegrass and spreading the sennegrass out over the snow so as to make a bed on which she and her companion could comfortably lie. It is fortunate that Gråen received this tender care from Camilla, for, well into the journey on December 5, a severe snowstorm buried him headfirst in a snowdrift where, tangled in his own harness and trace, and almost suffocated, he had to be rescued by Johansen. Gråen recovered immediately. With the severe weather, and with 3 days of being snowed in and snowed under, came less feedings for the dogs, who did indeed grow hungry on half the amount of food, as they hibernated beneath the snow over those 3 long days, wrote Johansen. At one point, during December 7, they even attempted to break into a case of pemmican, starving as they were.

But the dogs were soon fed their normal portion again on that day, resulting in a sleepless night, as Vulcanus – whom Prestrud described as an older dog with digestion problems – howled in pain all night (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 258). Presumably he was soon well again.

After digging out of the huge amounts of snow, the men began their return journey on December 9, especially as they were now running out of food. On December 12, after a 3-day long slog, the weather began to improve, and, as Johansen reported, the men calculated that there was just enough food to complete the return journey without having to detour to the depot of freshly killed seal that they had left along the way east (Johansen Expedition Diary b).

According to Kristian Prestrud, as relayed in his chapter of the book The South Pole, earlier during the expedition, around December 4, he had actually considered killing the dogs for food in order to lengthen his expedition and explore even more ground, but he dismissed this option. “There remained the resource of killing dogs, if it was a question of getting as far to the east as possible, but for many reasons I shrank from availing myself of that expedient,” he wrote (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 253). His reasons not to kill the dogs, he stated, included his uncertainty of how many dogs would return from the South Pole trek – if any returned at all, and his knowledge that the ten or so older puppies remaining at Framheim would not be able to transport supplies and provisions from the ship Fram to base camp should the expedition be required to spend another winter. Thus, keeping these 17 dogs alive was the sensible thing to do, he concluded, as they would be worth more as transport at Framheim than as food at King Edward VII Land – especially as he did not foresee discovering much more than the geological samples they had already found. There is no mention in Hjalmar Johansen’s diary, however, of contemplating this idea of killing the dogs.

And, so, the Eastern party, having managed to collect rock and moss samples, survive a blizzard, pack just enough food, and retain all their dogs, completed the trip home over the last few days of December 13 to December 16 (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 249 & 260).

As the Eastern party arrived in their old neighborhood on December 16, Framheim loomed in front of them as a welcome sight. Johansen wrote of the homecoming in his diary that day, focusing on the dogs’ reaction to coming home (Johansen Expedition Diary b): “When the dogs perceived the tents (which, by the way, were close to covered in drift snow) they took off in a gallop and arrived at the camp just as Lindstrøm was outside to take the observations.” 2

Lindstrøm, along with the remainder of the dogs, awaited the Eastern party at their home camp. The remaining dogs at Framheim, who had stayed with Lindstrøm, included Kaisagutten (Kaisa’s son), Lussi (Lucy’s daughter), and Stormogulen (Camilla’s son).

The other dogs who had remained at Framheim with Lindstøm most likely included some of the puppies born on the Fram, as well as a few of the original dogs from the ship, including Ester, Katinka, Bella, Lolla, Hviten (“The White”), Olava, Skalpen, Grim (“Ugly”), Pasato, Aja, and Lyn (“Lightning”).

According to Johansen’s diary entry on this day of December 16, some of the sled dogs remaining at camp had run away and not returned. Lindstrøm, on his own, had been unable to keep all of them together. “Some dogs he has lost, and some have returned,” wrote Johansen. 3 It is not certain which dogs these were. Lindstrøm was able to retrieve a team of young dogs, however, who he had harnessed to drive, and who had run away from him, only to be hunted down by a determined Lindstrøm, who, after a full night out searching on foot, fetched the puppies and brought them back home again (Johansen Expedition Diary). According to Prestrud, in The South Pole book, Lindstrøm had “ten or twelve dogs” at camp prior to the Eastern party’s departure (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 215) – but this must have been the number of dogs remaining at camp upon the Eastern party’s return.

Two days after the Eastern party’s return from King Edward VII Land, the men and dogs set out again to explore – this time to survey the eastern edge of the Bay of Whales, and this time with 12 dogs – 2 teams of 6 each (Johansen Expedition Diary b). Camilla, Liket, Gorki, and Pus were left behind at camp. The sled dogs, however, were eager to work, and those left behind were reticent to see the sledging party leave without them. Gorki and Pus, especially, would not take no for an answer. Johansen reported that they broke loose and chased the party, catching up with them on the following day of December 19. “We tried to chase them back to the meat-pots at Framheim, but no, they stayed behind the sledges at a respectful distance and would rather starve, as long as they could follow the teams, than have the good life at Framheim,” wrote Johansen in his December 22 diary entry. 4 As it turned out, Peary on Stubberud’s team developed a sore leg, and so was exchanged with Gorki who had been following behind.

A day later, the men and dogs of the sledging party were once again reunited with Lindstrøm and the dogs at home and proceeded to spend Christmas Eve and Christmas Day together at Framheim. “The only life is our dogs, that are but mostly lying still and panting in the warm calm weather,” wrote Johansen in his diary that Christmas Eve Sunday. 5

New Year’s Day 1912 saw the sledging party go out into the field again – this time to survey yet another area around Framheim. The men and dogs made a sledging expedition to the southwestern area of the Bay of Whales, which they traversed and studied from January 1 to 11 (Johansen Expedition Diary b; Amundsen 1912).

It was during this time that Fram came to port at the Great Ice Barrier’s edge, arriving on January 8, and slipping into the Bay of Whales, where, along the barrier above the vessel, the men and dogs of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition were dispersed for miles among the ice – in the surrounding vicinity of Framheim and on the return trek from the South Pole.

The Fram Returns from Buenos Aires

The day after Roald Amundsen and the South Pole party had reached the surface of the Great Ice Barrier on their northward return journey from the South Pole to Framheim; their dear ship the Fram reached the wall of the Great Ice Barrier in the Ross Sea on its southward return journey from Buenos Aires to Antarctica.

That date was January 8, 1912, and by this time, the ship had now more than once circumnavigated the globe. All in all, it had traveled 25,000 nautical miles on this leg of the journey, 8000 of which were charted during the oceanographic cruise conducted in the South Atlantic (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 344–346).

On the 9th of January, the Fram pulled in to the Bay of Whales but encountered high winds and treacherous ice that caused the ship to pull out again. After 2 days of going in and out of the bay, deftly dodging the drift ice coming in from the Ross Sea, the Fram moored in the Bay of Whales. The date was January 10. The crew then made ready to accept its passengers – the overwintering and hopefully successful South Pole party, which was expected to return to Framheim some time soon.

The ship had been at sea since October 5, 1911, bringing with it from Argentina all the food and provisions that Don Pedro Christophersen had so generously donated to Fram and to all of Amundsen’s expedition. Captain Thorvald Nilsen had negotiated the friendly deal with Christophersen, as well as negotiated the southern seas from South America, in order to return triumphantly to Antarctica.

The provisions on board included those imported from Norway by the Don, sent to Argentina, and given to the crew of the Fram: 50,000 liters (11,000 gallons) of petroleum, and all of the ship’s supplies to last an entire year (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 330). Also grazing on board were “fifteen live sheep and fifteen live little pigs,” compliments of Christophersen, of course (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 332). The animals were housed in special homes built for them on board the ship. The crew ended up eating six of the pigs in total during the sea voyage back to Antarctica and saving nine little pigs for the land party at Framheim. Rather than finishing off the pigs, once they had reached the Antarctic ice, the seamen instead shot seals along the way, to serve as fresh meat for the men at sea (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 344).

The eating of pigs was a tantalizingly tasty matter for most – but not all – of the crew. A. Olsen, who had been added to the crew during the ship’s first stop in Buenos Aires in June 1911, mourned his little pig Tulla who was killed for Christmas dinner. Captain Nilsen noted Olsen’s sadness and wrote about it in his chapter of the book The South Pole. “For a whole week before Christmas the cook was busy baking Christmas cakes,” wrote Nilsen. “I am bound to say he is industrious; and the day before Christmas Eve one of the little pigs, named Tulla, was killed. The swineherd, A. Olsen, whose special favourite this pig was, had to keep away during the operation, that we might not witness his emotion” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 339). As may be recalled, Nilsen himself had previously become quite attached to the animals on board – specifically to the sled dogs whom he had transported to the Antarctic. One wonders how he may have reacted to the killings of his favorite dogs as they occurred on the Great Ice Barrier and on the Polar plateau had he been there to witness these events.

Over their Christmas dinner of roast pork – presumably roasted Tulla – the captain and crew toasted “their Majesties the King and Queen, Don Pedro Christophersen, Captain Amundsen, and the Fram” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 340). They were cognizant of who had helped them – and they were grateful to Don Pedro Christophersen for the feast, for the supplies, and for enabling the ship to return to Antarctica to pick up the wintering party. After the dinner and Christmas ceremony were over, poor Olsen, bereft of his pet, was left alone to “clean out the pigsty.” No doubt he shed a tear at the empty space where Tulla had once resided. The pig had been his friend.

In regard to the other pets, Fridtjof the canary was still singing in his gilded cage aboard the Fram when the ship glided back into the Bay of Whales that January. The handsome yellow bird had become third engineer Halvardus Kristensen’s companion and now resided in his cabin on the ship (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 312). A cat, also, had been brought on board during the Fram’s second visit to Buenos Aires in September–October 1911. The cat excelled at catching rats, which Captain Nilsen deeply despised, and which he found, to his utter despair, had infested the ship. The cat was employed to rid the Captain of the vermin he so detested. The feline crewmember, unfortunately, later “was shot on the Barrier,” as reported by Nilsen (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 327). It is not known by whom or why he/she was killed, or if the dogs were given as a reason for the cat’s forced and untimely demise.

Whereas the trip from Antarctica to Buenos Aires the previous year had taken 2 months to complete, the return trip from Buenos Aires to Antarctica took three. And along the way in this second trip south, the crew had sighted their first icebergs on Christmas Eve, and the first ice floes to surround the ship on New Year’s Eve (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 339 & 342).

Four crewmen had been added in Buenos Aires during the first visit there in April–June 1911: H. Halvorsen, A. Olsen, F. Steller, and J. Andersen; and three had departed during the second visit to B.A. in September–October 1911: Alexander Kutschin, Jakob (Jacob) Nødtvedt, and J. Andersen; so that the Fram returned to the ice on January 10, 1912 with 11 men on board: Thorvald Nilsen, Ludvik (Ludvig) Hansen, Halvardus Kristensen, Hjalmar Fredrik Gjertsen, Andreas Beck, Martin Rønne, Knut Sundbeck, Karinius (Karenius) Olsen, H. Halvorsen, A. Olsen, and F. Steller (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 294–295, 331, & 316).

Upon the Fram’s arrival at the Great Ice Barrier on the afternoon of January 10, it was Lieutenant Hjalmar Fredrik Gjertsen who first stepped foot onto Antarctica from the ship, skiing straight over to Framheim and checking in with Adolf Lindstrøm at 1:00 p.m. that day. And it was a dog who first came down from Framheim to greet the ship and its crew. The dog’s visit made an impression on Captain Nilsen, who wrote about it in his expedition diary, stating that upon the ship’s arrival, a dog had run down from the ice to the vessel, probably following the tracks that Gjertsen’s skis had left behind (Nilsen 2011). Nilsen further expounded on this in his chapter of the The South Pole book that was devoted to the Fram’s journey: “Later in the afternoon a dog came running out across the sea-ice, and I thought it had come down on Lieutenant Gjertsen’s track; but I was afterwards told it was one of the half-wild dogs that ran about on the ice and did not show themselves up at the hut” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 346–347). This reference to “half-wild dogs” most likely alludes to the dogs and older puppies whom Lindstrøm had lost during the time that both the Eastern and the South Pole parties were away, and who had not returned to Framheim. The inference is that some of the dogs had by now presumably become inhabitants of Antarctica, and were no longer part of the expedition. It is not known which of the dogs specifically had become these “half-wild” dogs of Antarctica.

When the ship had arrived, Captain Nilsen at first had been reticent to let Gjertsen go ashore on his own, as the ice was dicey and the ship only had one pair of skis. Gjertsen convinced the captain to let him go, however, and, unescorted or unaided by dogs, he made his way up to Framheim and surprised Lindstrøm with his unexpected entrance. The two men quickly caught up and then laid an ambush for the unsuspecting three men who were still out on the ice – Johansen, Prestrud, and Stubberud – to likewise surprise them when they returned home (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 268 & 346). Those three explorers were, at that time, out on a mission with their sled dogs to survey the nearby vicinities of Framheim. They were engaged in this expedition when the Fram, unseen by them, had first come in (Johansen Expedition Diary).

On the next day of January 11, the three men – Johansen, Prestrud, and Stubberud – and their sled dogs returned from their 11-day surveying trip conducted in the southwest region of the Bay of Whales, which they had undertaken after their return from their expedition trip to King Edward VII Land on December 16 (Johansen Expedition Diary; Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 265–267). Upon their return to Framheim, Prestrud, Johansen, and Stubberud found the Fram’s Second Lieutenant Gjertsen hiding in a bunk at Framheim, springing up to surprise them as they entered. Lindstrøm had been in on the surprise and took great delight in this game. As the dogs liked to play outdoors, so, too, did the men like to play indoors.

The Fram, in the meanwhile, had set out again for another 24 h to escape the severe winds that were now blowing through the bay. On the 11th, the Fram was able to come in again and moored at the ice. This time, Lieutenant Gjertsen came back to the ship with Johansen, Prestrud, and Stubberud in tow, pulled by their sled dogs. “Our well-trained team were not long in getting there [to the Fram], but we had some trouble with them in crossing the cracks in the ice, as some of the dogs, especially the puppies, had a terror of water,” wrote Lieutenant Prestrud in his chapter of The South Pole book (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 270). Stubberud later wrote that, in the men’s enthusiasm to return to Framheim, they coaxed the dogs ahead – most likely via brandishing whips – and made haste to reach the Fram and see their old crewmates; in crossing the bay ice to reach their beloved ship, they encountered challenges, as some of the dogs fell into the water between the ice floes, and had to swim in the freezing cold bay and crawl back up onto the other ice on the other side (Stubberud 2011). Nonetheless, the dogs brought the men safely to the Fram, and, according to Stubberud, boarded the ship for the night.

The two long-separated parties from land and sea had a hearty reunion on the ship. Prestrud, Johansen, and Stubberud greeted their old crewmates and met with Captain Nilsen. The men gave each other the latest news and wondered about the state of the South Pole party. In a meeting that lasted until the following morning of the 12th, during which time their team of sled dogs waited patiently on deck, Captain Nilsen and Lieutenant Prestrud conjectured about the chances of Amundsen’s finding the South Pole. Amundsen, his men, and his dogs were still somewhere out there on the Polar ice. It was not known when – never expressed as if – they would return. But Captain Nilsen and Lieutenant Prestrud concurred, as Prestrud described, “that in all probability we should have our Chief and his companions back in a few days with the Pole in their pockets” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 271).

After this serious meeting, Prestrud took his cinematograph in hand and filmed the men greeting one another and shaking hands on board – a reenactment of their original meeting staged especially for the camera (Amundsen Film 2010). He also filmed engineer Knut Sundbeck – who was fond of dogs and who had been a close friend of Johansen’s dog Grim while on the sea voyage – now on the Antarctic ice, cavorting with an animal of another species specific to Antarctica, a penguin. The duo of man and penguin did a little silent dance duet together – an almost Chaplinesque performance that appears on film as both elegant and humorous. Graceful bows, waltz-like turns, and delicate side steps, wherein each partner was fully focused on the other, made this dance a miniature minuet between one tall and one short creature. One final bow to each other and the dance was done. 6

Now men, dogs, ship – and penguins – all awaited the return of the South Pole party.

The Mawson Expedition

Meanwhile, on the same date that the men and dogs of Roald Amundsen’s South Pole party found themselves again on the Great Ice Barrier surface during their return home from the South Pole, and the Fram crewmembers found themselves at the edge of the Great Ice Barrier’s imposing wall upon their return from Argentina – on this day of January 8, 1912 – all the way across the Ross Sea, on the near coastal side of Antarctica, past Robert Falcon Scott’s McMurdo Sound and Carsten Borchgrevink’s Cape Adare, an Australian expedition ship named the Aurora arrived at Adelie Land carrying members of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911–1914, under the command of Dr. Douglas Mawson.

Mawson had formerly been part of Ernest Shackleton’s second Antarctic expedition with the Nimrod in 1907–1909. He now headed his own expedition to Antarctica, which he conducted primarily for scientific reasons.

At the helm of the Aurora was the English-born Australian Captain John King Davis, commander of the ship and second-in-command of the expedition. He, too, had served under Shackleton during the Nimrod expedition of 1907–1909, along with Mawson.

Captain Davis and the Australian expedition had left London, England on the Aurora at midnight, July 27, 1911. According to Mawson, in his book The Home of the Blizzard, on board the ship were 49 howling, protesting Greenland dogs acquired for sledging purposes, and already travel-weary from the long trip from Greenland (Mawson [1915] 1969, vol. 1: 19–20). The ship first headed to Hobart, Tasmania, where they rendezvoused with Mawson on November 4, and from whence they had then all departed together on December 2, 1911, setting a course for Antarctica. According to Mawson, they by now had 38 dogs who had spent their time in Hobart in quarantine (Mawson [1915] 1969, vol. 1: 26).

Upon arriving at Adelie Land in Antarctica on January 8, 1912, after setting up stations along the Antarctic coastal region, the expedition established its Main Base at Cape Denison, Commonwealth Bay, from whence Dr. Mawson would conduct his many purely scientific and surveying studies.

The ship, captained by Davis, left the wintering party of Mawson, his men, and the sled dogs, at their Main Base on January 19, and began the journey back to Hobart from Antarctica.

Prior to their departure to Antarctica, around April of 1911, as the news of Amundsen’s audacious and gutsy foray into the Antarctic realm shook the world to its core, and after joining Mawson for their own planned expedition to Antarctica, Captain Davis had most likely had a few nice things to say about Amundsen. So had a Welsh-born Australian Professor of Geology in Sydney, by the name of Tannatt William Edgeworth David, who also happened to be President of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science. Professor David was another fellow veteran of the Nimrod expedition under Shackleton in 1907–1909. Together with Douglas Mawson, he had made the first sled journey to the South Magnetic Pole in 1908–1909 (Mawson [1915] 1969, vol. 1: xiii–xiv). Now this highly respected and credible Antarctic expert was part of the Australian expedition, one or two members of which eloquently sang the praises of Amundsen (Mawson [1915] 1969, vol. 1: 82).

Most likely, a certain Norwegian captain named Thorvald Nilsen, helming the Polar ship the Fram, and visiting Buenos Aires during April to June of 1911, and September to October of 1911, came across some positive comments published in interviews and news articles he had read while away from Antarctica. If he did so, he must have saved this interesting bit of news to tell his commander Roald Amundsen upon the explorer’s greatly anticipated return from the South Pole.

And this news would directly affect the lives, futures, and fates of the sled dogs of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition – some of whom, at this very moment, on January 8, 1912, were returning from the South Pole.

Dog Chart: The Sled Dogs Who Returned from the Eastern Expedition, in December 1911

Seventeen sled dogs, working on two sledge teams, successfully completed the Eastern expedition to King Edward VII Land, returning with the three men on December 16, 1911.

The names of the dogs, and the sled teams on which they worked, along with the names of their team drivers, are as follows:

Vulcanus (“Vulcan”, also Vulkanus)

Snuppesen (also Fru Snuppesen)

Brun (“Brown”)

Dæljen

Liket (“The Corpse”)

Camilla (also Kamilla)

Gråen (also Graaen and Gråenon)

Lillegut/Smaaen (“Little Boy” or “The Small One”)

Finn (also Fin)

Kamillo

Maxim Gorki (after the Russian writer Maxim Gorky)

Pus (“Kitty”, also Puss)

Funcho (also Funko)

Storm

Skøiern (also Skøieren)

Mons

Peary

The 35 sled dogs who remained at Framheim

Approximately 35 sled dogs had originally remained at the Norwegian Antarctic expedition base camp Framheim with Adolf Lindstrøm, most of whom were weaker adult dogs, several females, and young and older puppies. These dogs worked on short sledge trips around the camp during November and December 1911; however, some of these dogs left the camp and ran wild on the ice, living on their own, and thus reducing the number of dogs at camp to 11.

These sled dogs originally included the following 14 dogs:

Kaisagutten

Lussi

Stormogulen

Skalpen (“The Scalp”, also Skalperert; also known as Skelettet – “The Skeleton”)

Grim (“Ugly”)

Pasato

Lolla (also Lola)

Hviten (“The White”)

Ester (also Esther)

Lyn

Aja

Bella (also Bolla)

Olava

Katinka

The dog who most likely returned to Framheim

Fix – most likely returned from the beginning of the South Pole trek

These are the sled dogs of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition who made the first exploration of King Edward VII Land, and who remained at Framheim during the South Pole trek, in November–December 1911 through January 25, 1912.

Digging out from the snowstorm that snowed in the men and dogs of the Eastern party who made an expedition to King Edward VII Land. After being completely covered in snow for 3 days in the first week of December 1911, during which time some of the sled dogs became buried underneath the snow, the dogs, tent, and supplies were finally freed. Shown here are some of the sled dogs observing one of the men as he digs out the tent and sledge. (Photographer: unidentified/Owner: National Library of Norway)

Notes on Original Material and Unpublished Sources

- 1.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, November 12, 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:4

- 2.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, December 16, 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:6

- 3.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, December 16, 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:6

- 4.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, December 22, 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:6

- 5.

F.H. Johansen Antarctic expedition diary, December 24, 1911, NB Ms.4° 2775:C:6

- 6.

Author’s viewing of original film footage taken by R. Amundsen and K. Prestrud during the Antarctic expedition of 1910–1912, restored by the Norwegian Film Institute and released on DVD, 2010, as Roald Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition (1910–1912)