Leaving Antarctica

On January 30, 1912, in the Bay of Whales, 39 strong, intelligent, sturdy sled dogs, who had moved heaven and earth to bring a certain Norwegian explorer to the South Pole, and who had pulled tons of supplies and men across the unforgiving ice of Antarctica, were themselves pulled up the side of a ship, dangling helplessly by their harnesses, as they were brought back on board the Polar vessel Fram for its journey back home.

It was a most poignant sight witnessed by only a handful of men but imbedded into the memory of history via vintage film footage shot by the ship’s lieutenant Kristian Prestrud (Amundsen Film 2010). 1

The dogs had continued to work up until that very last moment (Amundsen Expedition Diary). The unpacking of Framheim and the preparations for departure were made possible only through them, for it was they who pulled sledge load after sledge load of supplies to the ship, toiling over those 4 days prior to the ship’s and the expedition’s departure and helping to load the ship in less than 3 days. For this reason, they were the last passengers to come on board.

Of these 39 survivors, 11 had been to the South Pole, 17 had worked on the Eastern trip to King Edward VII Land, and 11 had remained at Framheim (author’s research).

Mylius

Ring

Rap

Hai

Uroa (“Always Moving”)

Rotta (“The Rat”)

Fisken (“The Fish”)

Kvæn

Obersten (“The Colonel”)

Suggen

Arne

Vulcanus (“Vulcan,” also Vulkanus)

Snuppesen (also Fru Snuppesen)

Brun (“Brown”)

Dæljen

Liket (“The Corpse”)

Camilla (also Kamilla)

Gråen (also Graaen and Gråenon)

Lillegut/Smaaen (“Little Boy” or “The Small One”)

Finn (also Fin)

Kamillo (Camilla’s son)

Maxim Gorki (after the Russian writer Maxim Gorky)

Pus (“Kitty”, also Puss)

Funcho (Maren’s and Fix’s son)

Storm (Else’s son)

Skøiern (also Skøieren)

Mons

Peary

Kaisagutten (“Kaisa’s Boy”, Kaisa’s son)

Lussi (Lucy’s daughter)

Stormogulen (Camilla’s son born in Antarctica)

Fix

And seven of the following –

Skalpen (“The Scalp”, also Skalperert; also known as Skelettet – “The Skeleton”)

Grim (“Ugly”)

Pasato

Lolla (also Lola)

Hviten (“The White”)

Ester (also Esther)

Lyn (“Lightning”)

Aja

Bella (also Bolla)

Olava

Katinka

These dogs, through no choice of their own, of course, had been swept up in the events of history, and had made history in human terms, accomplishing significant achievements. The question remained, at the end of the expedition: What was to happen to them now?

There are hints in Roald Amundsen’s book The South Pole that Amundsen intended to destroy most of the dogs and keep only the best ones – most likely those who had reached the South Pole – as breeding stock for his upcoming voyage to the North Pole. But for the request of a certain Australian, received by Amundsen upon the Fram’s return from Buenos Aires to Antarctica, these non-South Pole dogs may quite possibly have been dispatched to the realm of eternity (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 181).

Fate in the form of Dr. Douglas Mawson intervened. It came through a message from the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, received by Captain Thorvald Nilsen during his Buenos Aires journey, that the Australians were in need of sled dogs and would be happy to borrow any that were no longer of use to Amundsen. Hence, Amundsen decided to take all 39 surviving dogs from Antarctica on board with him, and to present 21 of them to the Mawson expedition when they arrived in Hobart, Tasmania, which was his first port-of-call, as arranged by Captain Nilsen.

The 39 Dogs Who Left Antarctica

Upon boarding the Fram again for their departure from the ice, several of the dogs who had made the journey south to Antarctica immediately situated themselves in their old spots along the ship’s deck, where they had once congregated and resided with their caretakers (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 182). These included the following South Pole dogs: Obersten (“The Colonel”), Suggen, and Arne from Oscar Wisting’s team; Mylius and Ring from Helmer Hanssen’s team; and a “lonely” and bereaved dog whom Amundsen described as “the boss of Bjaaland’s team” – most likely Kvæn, whom Amundsen had previously listed first when naming Bjaaland’s team. According to Amundsen: Obersten was attended to by “his two adjutants” Suggen and Arne; Mylius and Ring resumed playing together “as though nothing had happened. To look at those two merry rascals no one would have thought they had trotted at the head of the whole caravan both to and from the Pole”; and Bjaaland’s dog – most likely Kvæn – searched in vain for “his fallen comrade and friend, Frithjof, who had long ago found a grave in the stomachs of his companions many hundreds of miles across the Barrier” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 182).

Thus, the dogs, and crew, occupying their familiar locations on the ship, departed from Antarctica and embarked on their 5-week voyage to Australia.

The voyage was a rough one. Toward the latter part of the journey to Hobart, during the rolling of the Fram in particularly violent waters and downpours of rain, on February 20, 1912, Maren’s and Fix’s son Funcho “fell overboard” and nearly drowned in the deep, icy, churning sea (Amundsen Expedition Diary). 2 He was saved by the one-time veterinarians Oscar Wisting and Hjalmar Fredrik Gjertsen, who plunged into the water after him, and, with the help of F. Steller, secured a rope around him and pulled him back up and into the ship. Amundsen wrote of the traumatic event in his diary. Most likely he had a special place, and a soft spot, for Funcho, the son of one of his favorite dogs, Maren, who herself had met her end by being washed overboard during a stormy night on the ship in November of 1910. Fortunately, Funcho did not die in the same manner as his mother had. Sverre Hassel, too, wrote of Funcho’s accident in his diary, describing the men’s quick and selfless actions to rescue him, Funcho’s valiant efforts to remain afloat, and the happy and lucky outcome to the story (Hassel 2011). Most likely, the crew was quite fond of Funcho, for the men had risked their lives jumping into the water to save him. Funcho was the only dog that Amundsen mentioned by name in his diary during the return voyage from Antarctica to Hobart. In fact, this would be the last time that Amundsen would write about any of his sled dogs in his Antarctic expedition diary.

It would not, however, be the last time that Amundsen spoke about the dogs, for he would give interviews to newspapers at length about the hard work and eccentric antics of his sled dogs and would later give lectures about this topic as well. In his first published interview and exclusive story upon landing in Hobart, released as a front-page article that featured a large photo of sled dogs prominently displayed at the bottom of the page, Amundsen stated: “I attribute my success to my splendid comrades and to the magnificent work of the dogs, and, next to them, to our skis and to the splendid condition of the dogs on landing in the Antarctic, due mainly to the precautions taken on the Fram” (The Daily Chronicle [London] 11 March 1912: 1). Dogs and skis, in that order, had helped Amundsen win his race. In this same newspaper article, he also relayed the story of Lucy and the three runaways – although he did not name any of these four dogs. And he spoke of “The first dogs … eaten on the journey to the Pole” who were killed at Butcher’s Shop – although he did not name Butcher’s Shop – and who “proved most delicious eating.” The newspaper reports, however, which devoted a lot of favorable ink to the dogs, reflected the impression that the killing and eating of the dogs had been necessary for the men’s survival. One headline boldly proclaimed that Amundsen was “forced to kill and eat his dogs” (The New York Times 11 March 1912: 1). Amundsen perhaps encouraged this perception. In a subsequent article, he seemed to show remorse for killing the dogs and gave his account in a manner that implied that the killings were all necessary: “I think what touched us most keenly on the whole journey was the unavoidable killing of dogs which had shared our dangers and done such splendid work. The killing of them went to the heart of every one” (The New York Times 12 March 1912: 1).

And, so, garnering sympathy for the explorer, Amundsen began his lecturing career of recounting how the sled dogs of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition had helped him discover the South Pole.

The 21 Dogs Who Returned to Antarctica with Mawson’s Australian Expedition

Three days prior to reaching Hobart from Antarctica, on board the Fram, the 21 sled dogs who had been selected to be presented to Douglas Mawson were prepared for the transfer. Astonishingly, these preparations included a change of identity for the dogs. According to Sverre Hassel’s diary entry of March 4, 1912, some of the sled dogs were given new names: for example, Skøiern became “Cook,” and Kaisagutten became “Kaisj” (Hassel 2011). The reason for the change of names was not given, but Hassel reported that Ludvig Hansen was producing name plates for the 21 dogs who were about to embark on a new Antarctic adventure.

It is interesting that Skøiern was given the name of Hjalmar Johansen’s deceased dog Cook, who had died during one of the depot trips, and that Kaisagutten was given a more ambiguous name that would not specify his being the son of Kaisa. Perhaps Amundsen wanted to give his dogs new and different identities as they endeavored to work on someone else’s behalf. This would seem, however, to create further challenges for the dogs, who would now need to learn their new names, in addition to learning a new language by which their new expedition members would speak to them.

The 21 dogs who were selected to be given to the Mawson expedition were the non-South Pole dogs – those who had not reached the South Pole. In his chapter of The South Pole book, Nilsen wrote that “Twenty-one of our dogs were presented to Dr. Mawson, the leader of the Australian expedition, and only those dogs that had been to the South Pole and a few puppies, eighteen in all, were left on board” (Amundsen 1912, vol. 2: 352). Hassel reiterated this point in his diary as well, that the South Pole dogs went on to Buenos Aires (Hassel 2011). It can be surmised, therefore, that most of the Eastern party dogs – those dogs who had worked on the King Edward VII Land expedition – as well as some of the dogs who had remained at Framheim were those dogs presented to the Australian expedition. The 21 dogs included Peary and Fix, who had begun the South Pole trek but had not reached it, returning instead back toward Framheim. (Nilsen’s and Hassel’s statements thus confirm that Fix did not reach the South Pole, as he was given to the Mawson expedition.) Peary and Fix retained their original names, according to their new dog driver Cecil Thomas Madigan, who cared for them as part of the Australian expedition in Antarctica and who mentioned that the two dogs had been on the South Pole trek (Madigan 2012).

Skøiern (also Skøieren)

Kaisagutten (“Kaisa’s Boy,” Kaisa’s son)

Fix

Peary

Vulcanus (“Vulcan,” also Vulkanus)

Brun (“Brown”)

Dæljen

Liket (“The Corpse”)

Gråen (also Graaen and Gråenon)

Lillegut/Smaaen (“Little Boy” or “The Small One”)

Finn (also Fin)

Maxim Gorki (after the Russian writer Maxim Gorky)

Pus (“Kitty,” also Puss)

Mons

Skalpen (“The Scalp,” also Skalperert; also known as Skelettet – “The Skeleton”)

Grim (“Ugly”)

Pasato

Lolla (also Lola)

Hviten (“The White”)

Ester (also Esther)

Lyn (“Lightning”)

Aja

Bella (also Bolla)

Olava

Katinka

Soon after the Fram’s arrival in Hobart, Tasmania, on March 7, an announcement was made that the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition would present 21 sled dogs to the Douglas Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition. The local newspapers documented the exchange, with one paper specifying that Professor Tannatt William Edgeworth David of the Douglas Mawson expedition had spoken favorably of Amundsen when Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova had first brought the news to the world that Amundsen was at the Bay of Whales attempting his run at the South Pole (The Mercury [Hobart, Tas.] 8 March 1912: 5). This same newspaper article also quoted the Aurora’s Captain John King Davis as having said originally, upon hearing the news of Amundsen’s foray into the Antarctic, that “he has a wonderful team of dogs, which will take him almost anywhere” and that “Captain Amundsen is a leader of men, and no difficulties will turn him back.” And, so, it is little wonder that Amundsen decided to give some of his prized sled dogs to Mawson’s Australian expedition – most likely as a hearty thank-you for the boost of morale and defense of reputation.

The 21 dogs, including Skøiern and Kaisagutten (Hassel 2011), and Peary and Fix (Madigan 2012), were made ready to disembark. They were brought off the Fram on March 13, 1912, and taken in rowboats to the outdoor Nubeena Quarantine Station (Hassel 2011; Nilsen 2011), located in windswept Taroona along the Tasmanian coast, where they were held in quarantine. They were accompanied by dog expert Sverre Hassel from the ship to the quarantine area, which he described in his diary as being a good space for them (Hassel 2011). Here, the dogs waited 9 months before boarding the Australians’ ship, the Aurora, on the day after Christmas, arriving at Commonwealth Bay in Antarctica on January 13, 1913, for a second tour-of-duty and yet another chapter of history. They disembarked at the Main Base – Cape Denison in Adelie Land – on February 8, ready to help yet another Antarctic expedition enduring a brutal winter and pursuing scientific discoveries.

Shortly after their arrival, 11 of the dogs regrettably were deemed too burdensome to keep – both for the men’s sakes and for their own sakes – and it was agreed that they would be killed (Mawson 1988; Madigan 2012). Douglas Mawson’s recent near-death experience and unfortunate missing of his ship, and the men’s realization that they would be trapped for another year, caused them to be concerned about keeping all the dogs over the winter. It would be a brutal winter for both men and dogs, they reasoned, as reported in Cecil Madigan’s diary (Madigan 2012). The decision and difficult selection of which dogs to keep were made on February 14, and the 11 dogs were shot on February 15. Both Mawson and his dog handler, Cecil Madigan, reported the killings in their respective diaries, in Mawson’s entry of February 16 and Madigan’s entries of February 14 and February 15. And, so, Mawson’s men killed half of the population of sled dogs who had worked with Amundsen in Antarctica and who had bravely traveled back to Antarctica to help the Australians. These 11 dogs were buried in the sea. They had come so far, only to be deemed dispensable.

Ten of the 21 dogs were kept alive to spend the harsh winter with the Australian men and their remaining three young pups, who were the only survivors from their teams of sled dogs who had perished on the ice. Cecil Madigan gave new names to all but two of the remaining 10 dogs he had selected to keep. Peary and Fix, whom Cecil Madigan believed to have completed Amundsen’s South Pole trek – although in actuality they had only begun the journey and turned back – retained their original names (Madigan [1913] 2010: 145; Madigan 2012: 353 and 452). The other eight dogs were renamed, some of them after Amundsen’s other dogs, about whom Madigan and the Australians had read in Amundsen’s newly published book The South Pole (Madigan [1913] 2010; Madigan 2012). Based on his statements in his diary and in his expedition newsletter The Adelie Blizzard, Madigan was under the mistaken impression that Peary and Fix had reached the South Pole, most likely because he had read only the first volume of Amundsen’s book, and possibly not the second volume, where it is disclosed that Peary backtracked from the South Pole journey and went on the Eastern expedition instead and that all of the South Pole dogs remained on the Fram in Hobart and thus were not given to the Australian expedition.

All 10 dogs worked the entire year as part of the Australian expedition in Antarctica and were cared for by Cecil Madigan, who became very fond of them. Of the 10 dogs, sadly two died in Antarctica – one, whom they had renamed Lassesen (Lasse), was put down as a result of injuries sustained from an attack by the other dogs, primarily by the three Australian Expedition pups, on April 23, and another, whom they had renamed Mary (which would be translated to Maren in Danish), during a second surgery conducted by the expedition doctor Archie McLean to relieve her of an illness, on October 30, 1913. Prior to her death, however, Mary had given birth to a puppy named Hoyle, on March 29 (Madigan 2012). Mary is described by Madigan in his expedition newsletter as having red and white coloring, a gentle nature, and good mothering instincts. It is a strong possibility that she is Katinka, Amundsen’s little red-haired female on the Fram who vied for his attention and who had been horrified when Maren had bitten her puppy.

Based on Madigan’s descriptions of the physical appearances and behavioral characteristics of all the 10 dogs that he inherited from Amundsen and that he kept alive, it is the author’s best estimation that the identities of these dogs were most likely as follows: Peary was Peary, Fix was Fix, Mary was Katinka, Lassesen (Lasse) was Lillegut, Amundsen was Pus, Colonel was Vulcanus, Fram was Mons, George was Gråen, Jack was Gorki, and Mikkel was Brun.

The eight surviving dogs, and the one newborn puppy, along with the expedition’s three remaining pups, left Antarctica with the expedition members on December 23, 1913, and traveled back to Adelaide, Australia, where the newspapers reported that only 11 rather than 12 dogs had arrived on February 26, 1914 (The Register [Adelaide, SA] 27 February 1914: 7; The Mail [Adelaide, SA] 28 February 1914: 1). There is the possibility, then, that one of the eight original dogs may have died on the ship, although Madigan does not mention this in his diary.

Peary, however, was one of the survivors who landed safely in Australia, identified by name in a news article (The Mail [Adelaide, SA] 28 February 1914: 1). And a dog matching Fix’s description was also part of the group who disembarked, described as “Samoyed” in a newspaper article (The Register [Adelaide, SA] 27 February 1914: 7).

All the dogs were housed temporarily in the Adelaide Zoological Gardens in quarantine, and most of them were, fortunately, adopted by the expedition members and crew (The Register [Adelaide, SA] 2 March 1914: 7). Two of the dogs who were adopted were Mary’s (Katinka’s) puppy Hoyle and the dog who had been renamed Amundsen (possibly Pus) – both taken by Cecil Madigan (Madigan 2012).

Two remaining dogs, however, were given by Douglas Mawson as a personal gift to the Zoo on April 7, 1914 – the date that they were released from quarantine – and were accepted by the Zoological Gardens and documented in their registries (Royal Zoological Society of S.A. 1914; South Australian Zoological and Acclimatization Society 1915; Rix 1978).

There is a strong possibility that Peary, and perhaps also Fix, were the two sled dogs who were gifted to the Zoological Gardens. Given Cecil Madigan’s concern that these two older, more independent dogs may not be adopted by an individual (Madigan 2012), and given that Peary was identified in the newspaper article as being one of the dogs at the zoo, as well as the fact that a dog matching Fix’s description was also mentioned in a newspaper, it is the author’s belief that the close friends Peary and Fix were the ones presented as permanent guests at the zoo. Peary, the sturdy black dog, had returned from the South Pole trek and completed the Eastern expedition. Fix, the gray wolf-like dog, had had his share of biting Amundsen and the crew of the Fram and defending his mate Maren. Most likely it was these two Greenland dogs, veterans of the Antarctic expedition, who now became permanent residents of the Adelaide Zoo.

And so this ended the trail of the Norwegian Expedition sled dogs who returned to Antarctica to work with the Australian expedition. They had been part of a community of 116 dogs who had contributed greatly to Antarctic exploration.

The 18 Dogs Who Went to Buenos Aires with the Fram

During the return voyage of the Fram from Antarctica to Hobart, in a diary entry dated March 4, 1912, Sverre Hassel confirmed that 18 of the 39 dogs would be left on board the Fram after the 21 dogs were given to Douglas Mawson’s Australian expedition (Hassel 2011). In that entry, he also mentioned that two of those 18 dogs were female. In actuality, there were at least three females remaining with the Norwegian expedition – Snuppesen, Camilla, and Lussi.

Mylius

Ring

Rap

Hai

Uroa (“Always Moving”)

Rotta (“The Rat”)

Fisken (“The Fish”)

Kvæn

Obersten (“The Colonel”)

Suggen

Arne

Snuppesen (also Fru Snuppesen)

Camilla (also Kamilla)

Kamillo (Camilla’s son)

Stormogulen (Camilla’s son born in Antarctica)

Funcho (Maren’s and Fix’s son)

Storm (Else’s son)

Lussi (Lucy’s daughter)

The above-named sled dogs include all 11 South Pole dogs, as well as seven dogs who were mentioned by the men in their diaries and letters as making the voyage to Buenos Aires or as being in Buenos Aires (author’s research). The only exceptions are Kamillo and Stormogulen, who are included in this list as, being the sons of Camilla, it is most likely that they accompanied her to Buenos Aires.

The Fram set sail from Hobart, Tasmania, on March 20, 1912, setting a course for Buenos Aires, Argentina (Nilsen 2011). Its now-famous commander, Roald Amundsen, was not onboard – he had already begun his lecture circuit in Australia that would take him to Sydney and to New Zealand and would later meet his ship, crew, and remaining 18 dogs once they arrived in the sunny South American city of Buenos Aires.

The Polar vessel’s captain, Thorvald Nilsen, continued his propensity to lavish the dogs with attention and faithfully wrote about their activities and challenges on board the Fram as the ship made its way north to Buenos Aires. His diary entries are full of anecdotes and information about the dogs during the journey at sea (Nilsen 2011). From his entries, we learn that Lussi – Lucy’s daughter and the only female born on the ship and allowed to live – had several comical close encounters with an albatross on the ship’s deck on March 29. Snuppesen – Amundsen’s red fox and friend of Fix and Lasse – became a mother, having eight puppies on March 31, as recorded by Nilsen in his diary on April 1. Four of Snuppesen’s puppies were killed – most likely thrown overboard, as Amundsen had done to all the female puppies – and four were allowed to live, two males and two females, bringing the canine contingent to 22 dogs on board. Rap suffered from seawater-caused pain in his front paw, and Storm – Else’s son – bit one of the toes on Camilla’s hind leg, as reported by Nilsen on April 9. Last, but not least, Hai attempted to procure for himself one of the live sheep provided by Don Pedro Christophersen as food supply on board the Fram – Hai was unsuccessful in his attempt, as duly noted by Nilsen on April 21.

The arrival of the Fram in Buenos Aires on May 23, 1912, coincided with Roald Amundsen’s own arrival in that city (Amundsen Expedition Diary; Amundsen 1912, vol. 2). Here the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition members finally met their benefactor Don Pedro Christophersen, who had financially saved their expedition. 4 Newspapers documented the historic meeting between Roald Amundsen and Don Pedro Christophersen.

According to a lengthy diary entry written by Sverre Hassel on June 8, recounting his days in Buenos Aires, the following series of events occurred that determined the immediate fate of the dogs (Hassel 2011). Christophersen and his family were invited to visit the Fram and its inhabitants on May 26. The elder statesman and successful businessman brought with him his two grown children – daughter Carmen and son Peter. They both fervently desired, and were promised by Amundsen, two of the dogs who had been to the South Pole. Most likely Amundsen, in contemplating the most special gift to give to his patron Christophersen, determined that this would be two of his South Pole dogs, whom he would deem as his most prized possessions from the expedition. On that day, most likely smitten by the young pups, Carmen took back home with her one of Snuppesen’s four puppies born en route to Buenos Aires. On the following day, Peter returned to the Fram and took the two South Pole dogs he and his sister had decided to keep: Uroa and Rotta. (Hassle’s diary entry thus confirms that Rotta had indeed made it to the South Pole.) All the remaining dogs were taken that day to the Buenos Aires Zoo and placed there on exhibition in an open area. Most likely, Amundsen wanted to exhibit his driving force in the Antarctic that enabled him to reach the Pole. Shortly thereafter, Uroa and Rotta caused a disturbance at Peter Christophersen’s home, stalking his resident goat and proving not to be household pets. They were reluctantly but promptly returned to Amundsen. Peter, very much wanting a dog from the expedition, traded the two dynamic sled dogs for one of Snuppesen’s puppies. Thus, Uroa and Rotta were also taken to the zoo, where they joined their fellow sled dogs on public display.

As would be expected, the dogs did not thrive at the zoo. On the contrary, it was a detrimental environment for them. Hassel reported in his June 10 diary entry that Amundsen and Nilsen went to visit the dogs on June 2 and found them in terrible condition – either too fat or too skinny, rained on incessantly, and very muddy (Hassel 2011). The only remedy proposed was to move them into an enclosed space which had previously been the bear house.

The heat and the close quarters did not make for an ideal temporary home for the heroic dogs. Accustomed to running and interacting in wide open space, their being imprisoned now must have been frustrating and demoralizing.

Soon, tragic news emanated from the zoo. As reported by Nilsen in his diary entry of June 12, Arne and Rotta both died in a fight (Nilsen 2011). To compound the sadness, Snuppesen’s two puppies who were adopted by the Christophersens both unexpectedly died of disease.

Arne and Rotta’s deaths were lamentable. They had been strong and tenacious dogs. Presumably their close proximity to other animals, lack of socialization with their men, and isolation among the crowds of strangers who came to watch them prompted the fatal aggression. As for the puppies, their deaths may have been the result of canine distemper.

And, yet, still, the rest of the dogs remained at the zoological garden. Amundsen, meanwhile, was writing his book The South Pole and had ensconced himself at Don Pedro Christophersen’s estancia in the Argentine countryside 3 (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence; Nilsen 2011), where he had been kindly invited to stay. Most of the crew and expedition members were already on their way back to Norway – again, courtesy of Christophersen (Hassel 2011). Only Nilsen and a handful of crew members remained on the Fram. By now, there were 18 dogs.

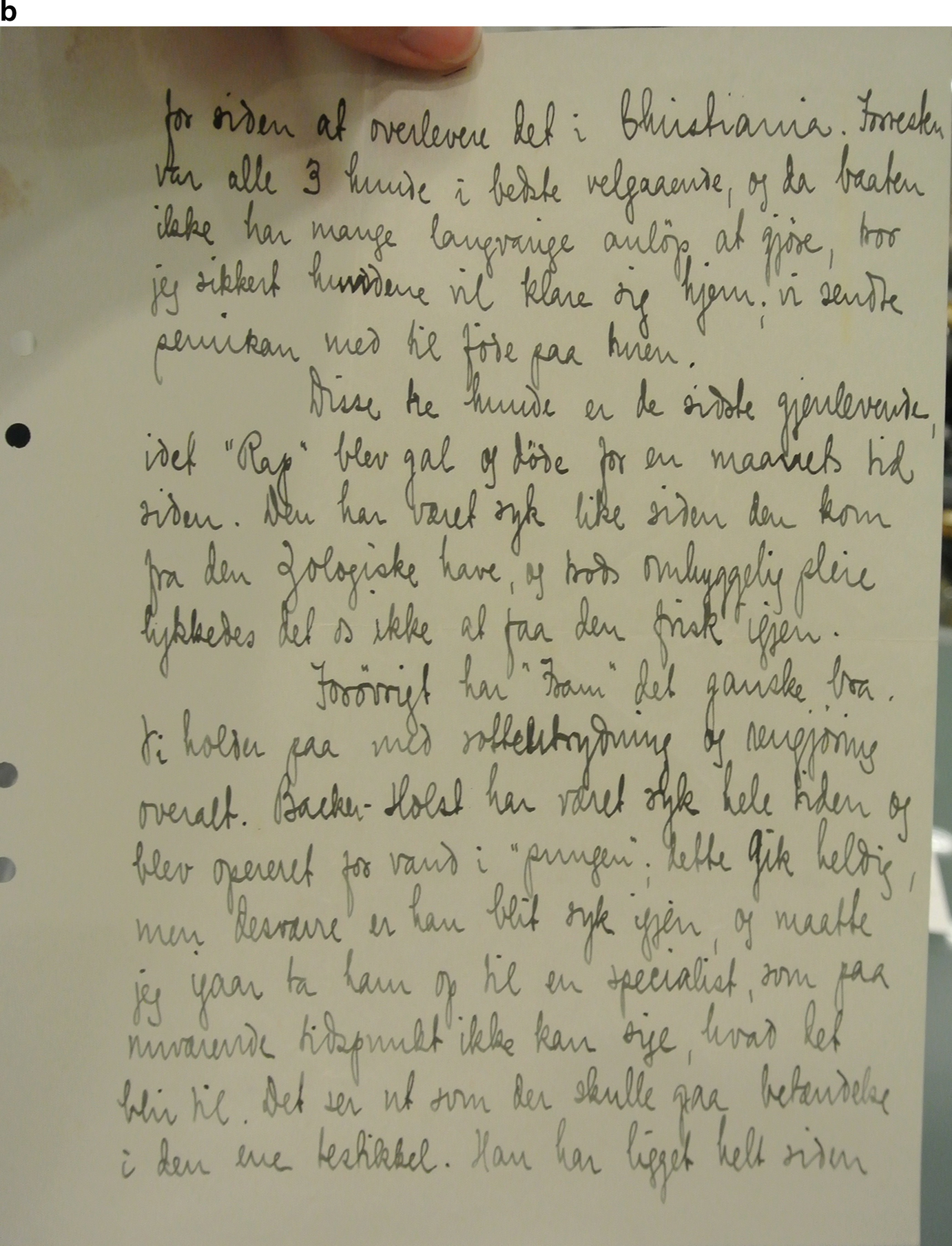

A little over 1 month after his diary entry reporting Arne and Rotta’s deaths, Nilsen wrote a letter to Amundsen about yet another casualty (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence). This time it was Funcho. Maren’s son had been bitten by one of the other dogs – but thankfully not fatally. “… I got the news that ‘Arne’ was dead, bitten in the head,” wrote Nilsen to Amundsen on July 18. “I went immediately to the zoo and there [found] also ‘Funcho’ had suffered a bite; he is, by the way, recovering.” 5 The dogs, stated Nilsen, had been moved to the facility’s basement, with smaller groups residing together in separate compartments. Uroa had been separated from the rest – he was now “alone.” Nilsen hoped that these new arrangements would prevent further fights; otherwise, he would bring the dogs back to the Fram. Nilsen specifically reported to Amundsen that the dogs were being “violent, especially ‘Obersten’ and ‘Uroa’.” With this trending violence among the dogs, it is a fair question to ask why the dogs were not removed from the zoo immediately. But they were not. A few weeks later, Nilsen again wrote to Amundsen reporting that the dogs at the zoo were now in better condition as a result of being moved into separate compartments and that “Funcho is all right.” 6

But the perceived calm was deceiving. One could say that it was the calm before the storm. And when the storm hit, it was devastating.

Sometime between August 6 – the date of this latest letter from Nilsen to Amundsen – and August 29, tragedy hit the zoo. The sled dogs were struck by an unknown illness – a debilitating disease that drained the very life from the dogs. Despite the efforts of the zoological director, the dogs succumbed to the sickness. Incredibly, inconceivably, most of the South Pole sled dogs died.

Eleven of the 18 dogs perished. Within a matter of a few weeks, they were gone.

What the freezing conditions of the Antarctic ice, and the smothering heat of the arduous sea journey couldn’t do, the good airs of Buenos Aires did. They carried, within the zoo, the microbes of an ailment that put an end to the sled dogs. Only several of the 18 dogs managed to hang on to life. And those who clung on just barely managed to do so. In their sickness and weakness, those few were brought back to the Fram.

The devastating news had come from Christian Doxrud, the soon-to-be interim captain of the Fram. In a letter that he wrote to Roald Amundsen, dated August 29, 1912, he informed the commander that “almost all of them [the dogs] are dead in the zoological garden” and that Nilsen “has taken the rest on board, but they do not look good.” 7 Doxrud reported that the remaining dogs would not eat and that the deceased dogs had died of a disease that could not be diagnosed.

The symptoms of the disease, unknown at the time, resemble those of canine distemper. The dogs probably contracted it at the zoo, where they were infected by other animals. It was a terrible consequence of imprisoning and placing on public exhibition these social, active beings who had crossed the oceans and bravely traversed the Antarctic continent.

The heroic dogs who had traveled to the end of the earth, who had worked so hard to reach the furthest point south where no living being had been, were dead in a zoo. Only seven had survived and had been brought back to the Fram, the nearest thing to a home that they knew.

Nilsen recorded the sad news in his September 5 diary entry, stating that the expedition now had only seven dogs remaining of all the sled dogs, as the majority had died of illness at the zoo, and that these seven were now all back aboard the Fram (Nilsen 2011).

Of the seven dogs who were taken back to the ship, five are known for certain, based on letters written by Nilsen (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence). They are Rap, Hai, Obersten, Lussi, and Storm. Therefore, all but two of the following dogs had died at the zoo: Mylius, Ring, Uroa, Fisken, Suggen, Kvæn, Snuppesen, Camilla, Funcho, Kamillo, Stormogulen, and Snuppesen’s two remaining puppies.

Too late, Amundsen learned of the fate of his remaining, favorite dogs. And too late, Amundsen expressed his regrets. They were sincere, but they were relegated to second place behind his desire to preserve the dead dogs as specimens – whether for science or currency is up for conjecture. Writing back to Nilsen on September 24, he stated that he was sorry to learn of the death of his wonderful animals and that the fate was probably unavoidable, but he also desired to have the dogs’ skins sent to him – the skin from all the deceased dogs (Nilsen 2011). Indeed, Amundsen went on to commission taxidermy versions of his dogs for perpetual display, to resurrect them in shape and color, sans spirit.

In his letter, Amundsen also admonished Nilsen to look after the remaining seven dogs. He was by this time writing and speaking about his sled dogs in lectures, which contained narrative about the killings of the dogs. This narrative showed up in a speech and paper he prepared for the Royal Geographical Society in London, which, when submitted in advance, caused the RGS’s esteemed secretary John Scott Keltie to plead with Amundsen to avoid this topic. In a letter to Roald Amundsen’s brother Leon, Keltie wrote, “I think also it may be as well to omit all mention of what he calls the ‘butchery’ of the dogs.” 8 To this request Leon Amundsen responded that his brother “asks me to thank you for your kindness but he regrets he can make no more alterations in his lecture.” 9 Amundsen would not flinch away from telling the world about Butcher’s Shop and the dispatching of the sled dogs. Meanwhile, the last seven of those very dogs lay suffering and in anguish on his ship Fram.

Two of the seven dogs died during the following month, sometime between September 5 and October 4. It seems that their sickness from the zoo could not be shaken. Nilsen recorded the news indirectly, stating in his October 4 diary entry that only five dogs remained on the ship (Nilsen 2011).

The five dogs were Obersten, Storm, Lussi, Rap, and Hai. The dogs were all, to varying degrees, ill from their disastrous stay at the zoo, and desperately attempting to regain their health. An expedition to the North Pole was still on the agenda and at that time was supposedly still in the cards for these dogs. Nilsen hoped that the improved atmosphere of living on the docked ship would revive the dogs. On October 8th, he wrote an assessment of the situation for Amundsen, noting in his letter to his commander that most of the dogs had begun to improve, but that two were not yet out of the woods. “Obest [Obersten] and Lucy [Lussi] are in pretty good shape,” he wrote. “Storm is improved considerably. But Rap and especially Hai are in very poor shape. When they walk, they sway like a drunk, or fall over. I think this fresher air, without sand blowing about, has an improving effect on them, and it is possible that they can live.” 10

Hai and Rap were swerving on the deck, as unsteady as a couple of inebriated sailors. The ship must have seemed to be constantly spinning around them. And most likely they were suffering unendurably. But Nilsen was hoping for the best, for a recovery in the improved environment of the ship rather than the zoo.

The best, however, did not seem to be panning out for these two sled dogs who had worked on the lead team that discovered the South Pole. One week later, on October 15th, Nilsen was again writing to Amundsen regarding Hai’s sickly situation, which had now become worse. “Hai is so sick that I am thinking of shooting him,” he wrote. “He kept me awake for hours last night with his whining. When he walks, it is mostly on the front legs, and with the hind half of his body dragging along the deck.” 11

The picture painted by Nilsen of Hai is a pitiful one, with the near-dead dog crawling along the deck, dragging the rear part of his body across the floor of the ship, crying with pain from the unbearable state of his being. It was a grim scene to behold and a ghastly sound to hear.

Hai cried into the night, his whimpers carried throughout the ship and over the water. It was the synthesized voices of the dogs who had served their human companions and perished – some of whom had been left to die. Nilsen could not let the suffering linger any longer. “Shot Hai yesterday evening, he was nearly dead and screaming incessantly,” wrote Nilsen on the following day – a note he added to the bottom of the last page of his October 15 letter, with the date of October 16 next to the note. 12

It was a difficult ending for a vibrant sled dog, who had always put himself in the middle of the action and who had served well on Helmer Hanssen’s sledge.

It was now down to four dogs remaining on the Fram: Wisting’s Obersten, Lucy’s daughter Lussi, Else’s son Storm, and Hai’s friend Rap. Of these four, the first three seemed to have recovered completely by October 21st. Still struggling, however, was Rap, who continued to battle the zoo-gotten sickness. “The dogs are the same,” wrote Nilsen to Amundsen in a letter dated October 21, 1912. “It seems like they are thriving pretty well. A bit boring it must be for them, of course. Rap is not well, but is drunkenly swaying around the deck.” 13

By this time, Amundsen was enjoying resounding success giving speeches about the South Pole expedition. He gave his famous lecture at the Royal Geographical Society in London on November 15, 1912, which was followed by the equally famous cheer and salutation delivered by the Society’s President, Lord Curzon – Earl Curzon of Kedleston: “I almost wish that in our tribute of admiration we could include those wonderful good-tempered, fascinating dogs, the true friends of man, without whom Captain Amundsen would never have got to the Pole. I ask you to signify your assent by your applause” (Earl Curzon 1913: 16). The remarks would become seared in Amundsen’s memory.

Two weeks after Amundsen’s presentation at the prestigious venue in England, Rap took his last breath in Buenos Aires and died on his ship, the Fram. It happened in early December, when the late Hai’s best friend followed his comrade to the end of his life. Rap’s life ended in much the same way as Hai’s had – with the madness of suffering and the insanity of pain. The howling that was heard on the Fram now was no longer the concert howling of former days, when the dogs would all join in unison to express their presence and their solidarity, but rather it was a single death wail, lone and pitiful. The ship’s new captain, Christian Doxrud, wrote of Rap’s final days, in a letter he sent to Roald Amundsen’s brother Leon Amundsen on January 4, 1913: “It [Rap] had been sick since it had come from the zoo, and, despite time spent taking good careful care of [Rap], it did not survive. We couldn’t succeed in getting it well again.” 14

Rap was the last to die on the Fram as the ship lay at anchor in Buenos Aires. His was the final death among the sled dogs to occur on that celebrated Polar vessel. Rap passed away around the date of December 4, 1912, physically and mentally tormented, the illness contracted at the zoo driving him to the end of his life.

There now remained only three surviving sled dogs on board the Fram in Buenos Aires: Obersten, Lussi, and Storm. On January 3, 1913, the three survivors boarded the steamship Prinsessan Ingeborg headed to Norway, as reported by Captain Doxrud in a letter to Leon Amundsen dated January 4, 1913. In addition to the three living dogs, Doxrud also sent back the skins of the deceased sled dogs, per Roald Amundsen’s request. “On the same ship are the dogs ‘Obersten’, ‘Storm’, and ‘Lucie’ …” wrote Doxrud. “These three dogs are the last living survivors, since ‘Rap’ went crazy and died one month ago.” 15

The three dogs arrived triumphantly in Christiania (Oslo) over 1 month later, on February 10, 1913, when the small water craft, the Helvig, steamed along the Christiania Fjord and docked near the formidable medieval castle Akershus, where the Fram had begun its journey into history nearly 3 years prior, and only a matter of miles from where Obersten had originally boarded the Fram at Flekkerö (Flekkerøy) Island. The three dogs stepped off the small passenger steamship to a welcome fit for heroic explorers and were greeted by the people of a nation whose flag they had been instrumental in having planted at the South Pole. They were escorted to a veterinarian, where they were checked and looked after by professionals (Amundsen Letters of Correspondence). Leon Amundsen reported on their arrival in a letter he wrote to his brother Roald on that day, saying that the three “have arrived very much alive” and that he was assigning their old friends the Antarctic expeditioners to take care of them – Oscar Wisting would look after Obersten (“The Colonel”), Jørgen Stubberud would look after Storm, and Martin Rønne would look after Lussi (Lucie). 16 It was Leon’s hope that Obersten and Lussi would mate and would successfully provide prized progeny – perhaps for the anticipated North Pole expedition. Even prior to their arrival, on February 6, he had already written to his brother Roald regarding breeding the dogs and putting them to work “for business purposes” either by “showing them off” or to “obtain a nice sale price.” 17 A few days after their arrival, on February 13, the rock-star sled dogs arrived at Amundsen’s home “Uranienborg” in Svartskog and, as reported by Leon Amundsen in his letter to Roald, “ran at full trot” with Stubberud across the fjord ice. 18

The three dogs lived together happily and peacefully in Roald Amundsen’s neighborhood, despite Leon Amundsen’s initial trepidations regarding their encounters with other animals and neighbors. But the dogs proved to be friendly with the neighborhood children, reenacting their sledge-pulling days for them, and allowing them to drive them across the ice, according to a letter from Leon to Roald Amundsen dated March 1, 1913, in which Leon stated that “The dogs were handsome and powerful.” 19

Soon after their arrival in February, Lussi and Storm were selected to take part in a rescue mission to save human lives. They were tapped to work on the rescue mission led by the Norwegian Captain Arve Staxrud, to search for and rescue members of the German Arctic Expedition led by Lieutenant Herbert Schroeder-Stranz, who were stranded in their iced-in ship, the Herzog Ernst, near Spitsbergen. Nervous about their fate and their safety, Roald Amundsen wrote to his brother Leon, on February 28th: “It pleases me to know that the 3 survivors are well at home. Hope now they manage the Spitsbergen trip. I will keep them – all 3. … The dogs – the 3 – should not be separated. It would be a great pity.” 20 Despite Amundsen’s concerns, Lussi and Storm went off to save the stranded expedition. “Obserten is home alone with Jørgen [Stubberud] and thrives excellently, the two others [Lussi and Storm] have traveled and Staxrud has been given strict orders to look properly after them,” wrote Leon to Roald Amundsen on March 10, 1913. 21 The two Antarctic sled dogs – Lucy’s daughter and Else’s son – departed for Spitsbergen in April, worked to find the stranded party of approximately seven men, and helped to successfully rescue them.

Amundsen, it seems, was very unsettled about his two sled dogs embarking on a risky expedition that could claim their lives. Leon found himself justifying his decision to Roald in a letter dated May 28, 1913, in which he wrote that, as Amundsen was not present himself, “I have found that it is impossible not to lend dogs to this expedition where human lives are at stake, but I commanded Staxrud to take proper care of them.” 22 Lussi, the only female puppy allowed to live during the Fram’s journey to Antarctica, and Storm, born on the Fram during stormy weather, had succeeded to save many human lives, heroically reaching the stranded men of the German expedition and pulling them across the northern ice to safety.

During Lussi and Storm’s absence on the rescue mission, on April 25, Leon asked Roald Amundsen if he would like the two dogs to go on the Fram’s next voyage to the north. 23 He also reiterated his doubts about keeping all three dogs at Amundsen’s home, although, by this time, Obersten was accompanying Stubberud to Uranienborg on a daily basis and had befriended Rex – Amundsen’s Saint Bernard who lived in his home and who had temporarily been relocated until the three Antarctic dogs could acclimate themselves to their new surroundings (most likely, Rex is the dog who was pictured with Amundsen at his home in front of the Fram). To this question of whether or not to keep the three Polar dogs, Amundsen most likely again responded that he would indeed like to keep the dogs, and to keep them together at his home, as, by early June, Obersten had permanently moved into Uranienborg.

It was in June that Leon put Obersten on the dog show circuit, despite Roald Amundsen’s reluctance to display him and to allow him to travel. Obersten succeeded to win several awards and medals, according to Leon Amundsen’s letters written to his brother Roald on June 4 and July 5, 1913, and to Amundsen’s sponsor Eilif Ringnes on June 16 and June 24, 1913. 24 The famous dog who had led Oscar Wisting’s sledge team to the South Pole proved to be quite a draw and a crowd-pleaser.

As of September 1913, the three dogs, Obersten, Lussi, and Storm, were reunited again at Amundsen’s home in Svartskog, following the return of the heroic rescuers Lussi and Storm from Spitsbergen and the return of the winning champion Obersten from the dog shows. The mating activities between Obersten and Lussi recommenced.

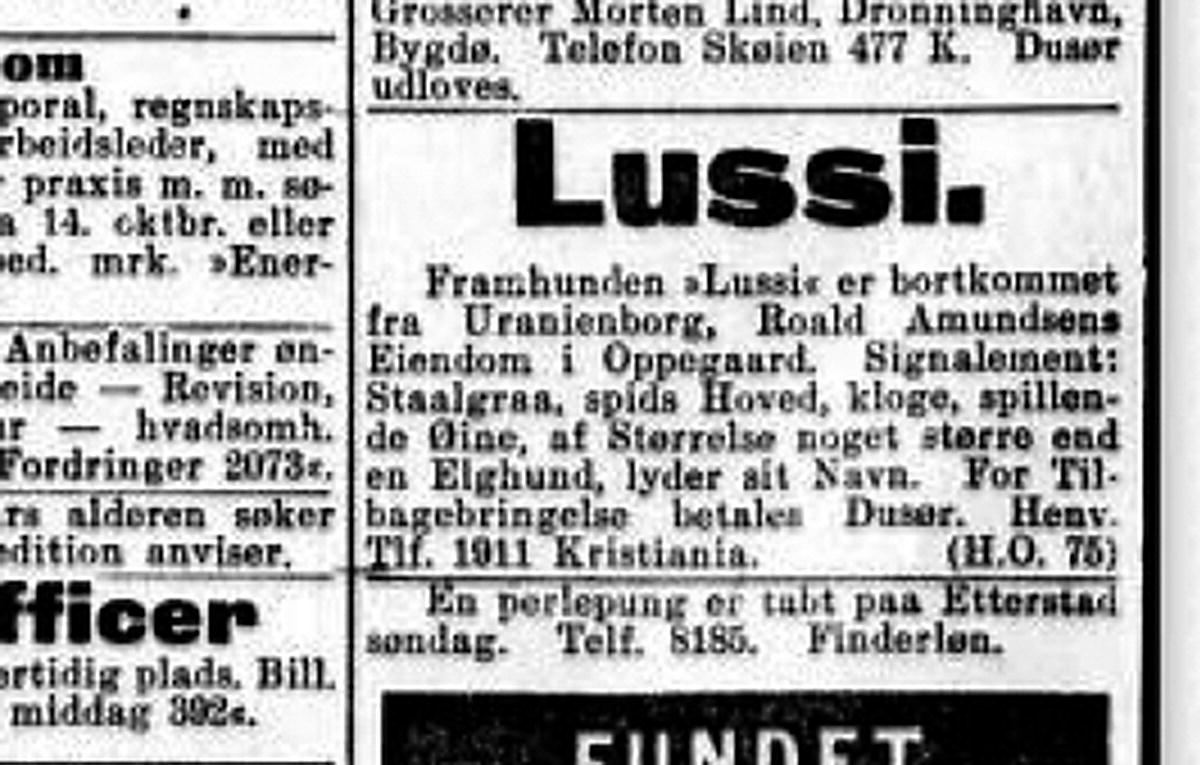

In what must have been a scare for both Leon and Roald Amundsen, Lussi evidently disappeared from Amundsen’s home briefly in October. A classified ad was placed in the Aftenposten newspaper on October 8, 1913, under the heading “Lussi,” offering a reward for “The Fram-dog ‘Lussi’” who “has been lost from Uranienborg, Roald Amundsen’s property” and who was described as “Steel-grey, pointed head, bright, lively eyes, of size somewhat bigger than an Elkhound, responds to her name” (Aftenposten [Oslo] October 8, 1913, Morning edition: 12). This, most likely, is the same Lussi. Lussi must have been found, or must have returned home again, because, on December 15th, Leon wrote to Roald Amundsen that “The dogs are doing excellently” and reported on “the little one,” who may possibly have been Lussi and Obersten’s puppy. 25 Leon also referenced Lussi again in a letter to Roald Amundsen on January 16, 1914, again discussing the status and ongoing efforts of breeding her so as to obtain a stock of puppy sled dogs and possibly for sale profits. 26 But later in that year of 1914, the three inseparable dogs were separated, with Obersten being sent to live with his Antarctic companion Oscar Wisting at his home in Horten. There, with Wisting and his family, Obersten was happy as well, playing with the children and basking in attention and fame … and food. 27 It would be his final home, where he died several years later.

For a time, however, the three sled dogs – Obersten, Lussi, and Storm – had been a happy family together at Amundsen’s home in Norway. They were the last, after all, of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition. They had been part of a population of dogs who had helped bring about one of the most important achievements in history – they had helped humans reach the last undiscovered place on earth.

Dog Chart: The 39 Dogs Who Returned from Antarctica

Thirty-nine sled dogs survived the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition and departed from the Bay of Whales, Antarctica, on the Fram , on January 30, 1912.

- The 11 South Pole dogs were:

Mylius

Ring

Hai (also Haika)

Rap

Rotta (“The Rat”)

Uroa (“Always Moving”)

Obersten (“The Colonel”)

Suggen

Arne

Kvæn (also Kvajn and Kven)

Fisken (“The Fish”)

- The 17 King Edward VII Land dogs were:

Vulcanus (“Vulcan,” also Vulkanus)

Snuppesen (also Fru Snuppesen)

Brun (“Brown”)

Dæljen

Liket (“The Corpse”)

Camilla (also Kamilla)

Gråen (also Graaen and Gråenon)

Lillegut/Smaaen (“Little Boy” or “The Small One”)

Finn (also Fin)

Kamillo

Maxim Gorki (after the Russian writer Maxim Gorky)

Pus (“Kitty,” also Puss)

Funcho (also Funko)

Storm

Skøiern (also Skøieren)

Mons

Peary

- The 11 Framheim dogs were:

- Definitely the following four dogs:

Kaisagutten

Lussi

Stormogulen

Fix

- Seven of the following dogs:

Skalpen (“The Scalp,” also Skalperert; also known as Skelettet – “The Skeleton”)

Grim (“Ugly”)

Pasato

Lolla (also Lola)

Hviten (“The White”)

Ester (also Esther)

Lyn

Aja

Bella (also Bolla)

Olava

Katinka

Their Final Destinations

Of the 39 sled dogs who returned from Antarctica, 21 were given to the Douglas Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition, and 18 traveled to Buenos Aires with the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition aboard the Fram.

The 21 who returned to Antarctica with the Australasian Expedition in December 1912–January 1913 were:

Skøiern, Kaisagutten, Fix, Peary, Vulcanus, Brun, Dæljen, Liket, Gråen, Lillegut/Smaaen, Finn, Maxim Gorki, Pus, Mons, and seven of the following – Skalpen, Grim, Pasato, Lolla, Hviten, Ester, Lyn, Aja, Bella, Olava, and Katinka.

Of these 21 dogs, 11 were killed soon after arrival in February 1913, and 10 were kept alive: These 10 were definitely Peary and Fix and – based on their descriptions (as they were renamed) – possibly Pus (renamed Amundsen), Vulcanus (Colonel), Mons (Fram), Gråen (George), Gorki (Jack), Brun (Mikkel), Lillegut/Smaaen (Lassesen/Lasse), and Katinka (Mary). With the death of the latter two, only seven or eight survived to return with the men to Australia in February 1914. Of these, all were adopted by the expedition members, with the exception of two – most likely Peary and Fix – who were gifted to the Adelaide Zoo.

The 18 who traveled to Buenos Aires with the Norwegian Expedition in March–May 1912 were:

Mylius, Ring, Rap, Hai, Uroa, Rotta, Fisken, Kvæn, Obersten, Suggen, Arne, Snuppesen, Camilla, Funcho, Storm, Lussi, and most likely Kamillo and Stormogulen.

Of these 18 dogs, all died at the Buenos Aires Zoo or – as a result of zoo captivity – on the Fram , with the exception of three remaining survivors: Obersten, Lussi, and Storm. The three survivors returned to Norway in February 1913, where Obersten won exhibition medals, and Lussi and Storm saved lives as part of the Arve Staxrud Norwegian rescue mission sent to Spitsbergen to save the stranded members of the Herbert Schroeder-Stranz German Arctic Expedition.

These all were the sled dogs who had helped discover the South Pole.

Front page article in the March 11, 1912, edition of The Daily Chronicle, the top of which featured a map of the route taken by Roald Amundsen to the South Pole and the bottom of which featured a photo of sled dogs. (National Library of Norway)

The bottom portion of The Daily Chronicle front page article on March 11, 1912, placing a spotlight on the sled dogs. Roald Amundsen was quoted at length about the sled dogs in his interview and in the articles. (National Library of Norway)

A page from the letter written by Captain Thorvald Nilsen to Roald Amundsen on July 18, 1912, informing Amundsen of the first deaths that had occurred among the sled dogs as they were being held in the Buenos Aires zoo and of the general conditions of the dogs’ captivity. (National Library of Norway)

In this letter dated October 7, 1912, written to Leon Amundsen, the Royal Geographical Society’s secretary J. Scott Keltie politely requests that Roald Amundsen not broach the topic of “the ‘butchery’ of the dogs” in his upcoming paper and lecture. (National Library of Norway)

The letter from the Fram’s new captain, Christian Doxrud, to Roald Amundsen’s brother, Leon, announcing the death of Rap in Buenos Aires in early December 1912 and the sending home of Obersten, Lussi, and Storm to Norway on January 3, 1913. This written correspondence, dated January 4, 1913, documents the last death of a sled dog on board the Fram and the last three remaining survivors from the South Pole and Antarctic Expedition sled dogs, who had been taken to Buenos Aires. (National Library of Norway)

Leon Amundsen informs his brother Roald that Obersten, Storm, and Lussi (spelled here Lucie) have arrived safely in Oslo (Christiania) from Buenos Aires, in this letter dated February 10, 1913. Obersten was the last surviving South Pole dog, Storm was born on the Fram during its voyage south, and Lussi was the only female puppy allowed to live during the ship’s journey to Antarctica. (National Library of Norway)

After returning from a lifesaving rescue mission in the Arctic, during which she and Storm had saved the lives of stranded German expedition members, Lussi went missing from Roald Amundsen’s home. This classified ad was placed in the October 8, 1913, morning edition of Aftenposten, appealing to anyone who had seen her. She was later found and resumed life at Uranienborg. (Aftenposten newspaper references, National Library of Norway)

Roald Amundsen’s home Uranienborg in Svartskog, Norway, where Obersten, Storm, and Lussi came to live after returning from Antarctica. Amundsen expressed to his brother Leon many times, in written correspondence, that he wished to keep the three dogs together at his home. After employing 115 sled dogs in Antarctica, and returning with only 39, during which time attrition was not a concern for Amundsen, he now desperately wanted to keep these three dogs safe and alive. (Photograph by Mary R. Tahan)

The dog house in the backyard of Roald Amundsen’s home in Norway, where the sled dogs Obersten, Storm, and Lussi – after their return from Antarctica – cohabitated with Amundsen’s Saint Bernards and other dogs who lived at home. Roald Amundsen hoped to emulate the same family feeling he had created with the sled dogs at Framheim, at his home Uranienborg just outside of Oslo. The sled dogs had brought him to the South Pole, and he wanted to bring the last three survivors home, where they would remain with him in Svartskog. (Photograph by Mary R. Tahan)

Notes on Original Material and Unpublished Sources

Roald Amundsen’s expedition diary, quoted in this chapter, is in the Manuscripts Collection at the National Library of Norway (NB) in Oslo. (The excerpts quoted are translated from the original Norwegian.)

- 1.

Author’s viewing of original film footage taken by R. Amundsen and K. Prestrud during the Antarctic expedition of 1910–1912, restored by the Norwegian Film Institute and released on DVD, 2010, as Roald Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition (1910–1912)

- 2.

R. Amundsen Antarctic expedition diary, 20 February 1912, NB Ms.4° 1549

- 3.

R. Amundsen to L. Amundsen, letter, 15 June 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 4.

Mercedes Christophersen, Alejandro Christophersen, and Jorge Christophersen, descendants of the Don Pedro Christophersen family, conversations with the author, Buenos Aires, 27–30 March 2011 and 12 January 2012

- 5.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 18 July 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 6.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 6 August 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 7.

C. Doxrud to R. Amundsen, letter, 29 August 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 8.

J.S. Keltie to L. Amundsen, letter, 7 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:2:i (Royal Geographical Society)

- 9.

L. Amundsen to J.S. Keltie, letter, 19 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:3:6

- 10.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 8 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 11.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 15 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 12.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 15 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 13.

T. Nilsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 21 October 1912, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 14.

C. Doxrud to L. Amundsen, letter, 4 January 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 15.

C. Doxrud to L. Amundsen, letter, 4 January 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 16.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 10 February 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1:R.A.6

- 17.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 6 February 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6

- 18.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 13 February 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 19.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 1 March 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6

- 20.

R. Amundsen to L. Amundsen, letter, 28 February 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 21.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 10 March 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6

- 22.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 28 May 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6

- 23.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 25 April 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6

- 24.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 4 June 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6;

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 5 July 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1;

L. Amundsen to E. Ringnes, letter, 16 June 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.6; and

L. Amundsen to E. Ringness, letter, 24 June 1913, NB Brevs. 812:3:R.A.7

- 25.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 15 December 1913, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 26.

L. Amundsen to R. Amundsen, letter, 16 January 1914, NB Brevs. 812:1

- 27.

Knut Wisting, grandson of Oscar Wisting, conversation with the author, Oslo, 16 March 2011