Go down in Alabama,

Organize ev'ry living man,

Spread the news all over the lan’

We got the union back again!

—“This What the Union Done,” ca. 1930s

We ought to handle you reds like Mussolini does ‘em in Italy—take you out and shoot you against the wall. And I sure would like to have the pleasure of doing it.

—Birmingham detective J. T. Moser, 1934

After three years of sustained activity, Communist-led trade unions remained virtually nonexistent in Birmingham's mines and mills. Unlike the urban jobless and rural poor who comprised the Party's rank-and-file, employed industrial workers had much more at stake. Knowing full well that their jobs could easily be filled by desperate soldiers in the reserve army of labor, few could afford to openly associate with Communists. But as Birmingham moved deeper into the throes of depression, conditions deteriorated to such a degree that even workers able to hold on to their jobs found it increasingly difficult to survive. In 1931, TCI-owned mines and mills cut wages by 25 percent followed by a 15 percent reduction in May 1932. More devastating for workers, however, were cutbacks in operations that effectively forced large numbers of employees to accept work on a part-time basis. TCI, Sloss-Sheffield, and Woodward Iron Company implemented a three-day schedule in 1931, and some steel workers and miners worked as little as one or two days per month.1

Birmingham's industrialists chose to reduce hours rather than lay off the bulk of their labor force in order to retain cheap labor in case market fluctuations created a sudden demand. While some workers found jobs elsewhere, the peculiar structure of the company-owned settlements held most in residence, reducing them to virtual peons of their employers. Whether the settlements were located in an isolated mining community or owned by a steel company in an industrial suburb, they shared numerous similarities. Residents of the company-owned homes were at the whims of their employers—any challenge to the rules or breech of agreement, written or spoken, could lead to eviction. Because rent was so inexpensive (about five or six dollars per month in 1930), few workers chose to strike out beyond the company settlement. More importantly, companies generally did not evict workers unable to pay the rent, choosing instead to retrieve back payments through payroll deduction at a later date. The apparent gesture of goodwill had its price: resident workers living under this arrangement had to work upon request, irrespective of minor ailments or other related problems, and those who failed to show were either threatened or beaten by the company's “shack rouster” or were promptly evicted.2 Structured along the lines of an armed camp and resembling in some ways South Africa's mining compounds, the company-owned settlements were also intended to insulate workers from outside influences, namely labor organizers. Employers maintained a private police force, paid spies to collect information and monitor workers’ activities, and employed every available means to create an impenetrable shield around the community.3

Company suburb: double-tenant shotgun houses line streets just outside Republic Steel plant in Birmingham (Farm Security Administration photograph, courtesy Library of Congress)

In addition to wages and living space, employers used commodities, mainly food, to retain and control industrial workers. The less expensive private grocers were naturally workers’ first choice, but most employers paid wages in scrip worth about sixty cents on the dollar, to be used exclusively at the company commissary. Even when workers received direct wages, the availability of credit created a cycle of dependency not easily broken. And miners who resided in isolated settlements had few alternative establishments with which to trade.4

Reductions in wages and hours during the early 1930s increased workers’ debts to the point where other means of survival were not only necessary but encouraged by employers. Like most Birmingham unemployed, miners and steel workers turned to gardening and keeping livestock, especially chickens and pigs. TCI and other large companies encouraged cultivation by renting land to employees at an incredibly cheap rate and making company-owned mules available for plowing. These worker-owned gardens were cultivated primarily by women, whose presence the company clearly took advantage of as a reservoir of free labor. In communities with few employment opportunities for women, the companies indirectly benefited from the labor of workers’ wives and daughters because unpaid household and agricultural work was necessary to reproduce the labor power of male industrial workers. In addition to cultivating gardens, these women canned goods, made clothes, washed dust-stained “muckers” (work clothes), repaired homes, and to survive the freezing winters without heat, made quilts. “The houses was as cold as I don't know what,” recalls Louise Burns, the wife of a black Alabama coal miner who remembers spending much of her time making quilts, gathering coal, and patching up holes in the walls. “We did all this stuff to help keep things warm and going the best we could. Yeah. We had plenty to do.” In some cases, the exploitation of female labor was more direct. Foremen and high-ranking officials often had their laundry washed by workers’ wives and daughters for as little as fifty cents per load.5 Women's unpaid labor and the proliferation of gardens certainly ensured family survival, but these practices also helped the company by mitigating reductions in wages and hours without seriously damaging the social reproduction of labor. In other words, the burden of survival fell increasingly upon the shoulders of women, not as paid workers contributing household income directly, but as unpaid producers whose labor ensured the maintenance of the industrial worker.6

For the most part, this tenuous mode of survival, visible mainly in the form of company paternalism, worked against labor activism, especially during the pre-New Deal period. The availability of work, credit, “free” rent, and land for cultivation, instilled a sense of complacency within the labor force, and any rumblings of opposition were quickly crushed by threats, intimidation, or violence. Early in 1930, for example, when no more than a dozen Communists roamed the streets of Birmingham, the AFL launched a massive campaign to organize white Alabama textile workers, of whom some 85 percent lived in company towns. Yet, even with the support of several state political figures, including Governor Bibb Graves, the drive completely failed. Although the campaign was conceived in response to North Carolina's Communist-led textile strikes in 1929, opponents harkened back to those very events to depict the conservative AFL organizers as “a band of invading agitators, who were coming from the outside to disrupt the peace and harmony” between labor and capital.7

The utter failure of the AFL's organizing drive was a foreboding of the Communists’ first three years as labor activists. Aside from intermittent attempts to organize bakery workers and black women employed in Birmingham's burgeoning mechanical laundries,8 Communists concentrated exclusively on building the NMU and the Steel and Metal Workers’ Industrial Union—both affiliates of the TUUL. From its beginnings in 1930–33, the NMU failed dismally in Alabama, partly because its dual-union tactics were ineffective in a region with no competing labor organizations. In other areas the NMU sought to attract renegade UMWA members into its own ranks or to build a groundswell of opposition to UMWA leaders. Birmingham NMU organizers, however, had to build an interracial union from scratch. Not surprisingly, their early efforts bore little fruit. Communists barely penetrated the armed mining camps, and following a spate of arrests and beatings by TCI police, the fledgling NMU eventually abandoned its campaign.9

The Steel and Metal Workers’ Industrial Union did not fare much better during the pre-NRA period. In 1931, Communist shop units at the Stockham Pipe and Fittings Company and the U.S. Pipe Shop called for a walkout in response to a general 10 percent wage cut, but workers ignored the strike call. Yet, the dual-union policies proved slightly more effective in steel because of the presence of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, a considerably weak craft union that had been in existence since the early part of the century. The Communists assailed Amalgamated for practicing racial discrimination and ignoring the unskilled, prompting dozens of black steel workers to protest the union's exclusionary policies. By the time Amalgamated launched its organizing drive under the NIRA, complaints from black workers compelled the union to open its ranks, although its president, W. H. Crawford, was quick to explain publicly that the “union, of course, is not seeking to elevate the negro.”10

Alabama's languishing labor movement was given an unprecedented boost in 1933, when Congress passed the NIRA. The provisions established under section 7(a) stipulated that in the industries covered under the NIRA code, employees could not be prevented from joining a labor union. Employers also had to pay minimum wage rates and to observe regulations setting the maximum hours of work as well as other employment rules set forth in the NIRA for their respective industries. Labor responded with renewed enthusiasm; only two months after the NIRA was signed into law, an estimated sixty-five thousand workers joined unions affiliated with either the Birmingham or Bessemer trades and labor councils. The resurgence of industrial labor organization was most apparent in the Alabama coal fields. Under the leadership of Indiana labor organizer and former Socialist William Mitch, the UMWA initiated a successful campaign during the summer of 1933 and reorganized Alabama's District 20 within a few months. Despite retaliatory layoffs and evictions, by August eighty-seven locals had been organized throughout the state, and within months thousands of miners walked off their jobs demanding union recognition.11

The Communists were unimpressed by the NIRA, arguing that it was intended to force workers into company unions. Alabama Party leaders criticized the act for not covering agricultural and domestic workers and for imposing regional wage differentials, accurately predicting that industrialists would respond by replacing black labor with whites rather than pay blacks the sanctioned minimum wage.12 Nonetheless, Birmingham Communists responded eagerly to the sudden surge of labor activity, and by mid-1933 organizing the unorganized replaced joblessness as their primary issue. At the CPUSA's Extraordinary National Conference held in New York in July, delegates issued an “Open Letter to All Members of the Communist Party” calling for an intensification of trade union work. Birmingham Communists signaled the new emphasis on organized labor by holding an unemployed and trade union conference two weeks before the 1933 elections. Although most of its organizers were arrested before the meeting began, the conference was supposed to be a forum to discuss the labor movement's future and to develop strategies for establishing rank-and-file committees within the unions. The Party further highlighted the new line by nominating two TCI employees to run for Birmingham city commission in the 1933 elections. Mark Ellis, a young, white, trade union organizer and Communist candidate for commission president, shared the ticket with black TCI steel worker David James, who ran for associate commissioner. Their campaign platform focused mainly on building the labor movement and securing the right to organize. They continued to advocate more relief and an end to evictions of unemployed workers and vowed to cut the police budget, arguing that it would not only free money for municipal relief projects but reduce antilabor repression and police brutality throughout the city.13

The Party's industrial organizing campaign took hold rather quickly. The number of Communist shop units in Birmingham increased from five to fourteen within a few months, and by January 1934 Alabama had 496 dues-paying Communists.14 In accordance with Central Committee directives, the Alabama cadre also made a greater effort to recruit more whites. While they hoped to draw progressive white industrial workers, what they got was an eclectic mix of hoboes, ex-Klansmen, and intellectuals who had been reduced to semipoverty by the depression. An example of the latter was Israel Berlin, a thirty-two-year-old Lithuanian-born Jew who held a B.S. degree from the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. After losing his job as a chemist and failing to secure a commensurate position, Berlin spent much of his idle time studying the economic crisis. Dissatisfied with Republican and Democratic panaceas, Berlin joined the Communist Party in 1933 and became its full-time literature agent in Birmingham.15

Clyde Johnson, ca. 1937 (photograph by Dolly Speed, courtesy Clyde Johnson)

The local cadre was also infused with talented individuals from outside the South. The New York-born Jewish radical Boris Israel had already gained notoriety in Memphis for leading several unemployed demonstrations and for defending a black man accused of raping a white woman. By December 1933, police and vigilante pressure had forced him to take refuge in Chicago, but he returned South a few months later. Adopting the pseudonym “Blaine Owen,” he settled in Birmingham in 1934 and resumed his work on behalf of the Communist Party. The addition of Clyde Johnson, a lean, tall, soft-spoken young Communist organizer, benefited the industrial campaign immensely. Born in 1908 in Proctor, Minnesota, Johnson was only fifteen when the Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railroad hired him to work during the summers. After two years at Duluth Junior College, in 1929 he moved to New York and secured work as a draftsman for Western Electric Company while attending courses at City College of New York. Drawn immediately to the campus Left, Johnson emerged as a leading militant at CCNY, was elected national organizer for the NSL, and joined the Communist Party. Accompanied by Don West, a radical Southern preacher and poet who would also join the CP, Johnson was dispatched to Rome, Georgia, in 1933 at the behest of the NSL to assist in a student strike at Martha Berry School. Johnson remained in Rome, helped lead a strike of foundry workers, and briefly organized farmers for the Farm Holiday Association. Harassed, arrested, beaten, and eventually forced to flee the county, he left Rome and headed for Atlanta to replace the incarcerated Angelo Herndon; there he met ILD activist and future wife, Leah Anne Agron. Reassigned to Alabama in 1934, he soon became the Party's leading labor organizer in the Birmingham district.16

By the time Johnson and other Communists began organizing coal miners in Walker and Jefferson counties, many of the obstacles that had hindered the TUUL during the pre-New Deal era no longer prevailed. Communists could now work as an alternative force within existing industrial unions that enjoyed limited support from the federal government. More importantly, the horrible living and working conditions in both the coal and ore mines had effectively nourished labor militancy. Accidental deaths caused by falling rocks, cave-ins, uncontrolled loading cars, or natural gas explosions occurred often, and workers disabled or suffering from lung-related diseases received no benefits. Coal operators avoided responsibility by contracting out work to skilled white miners who would hire their own loaders, blasters, and common laborers. When workers complained about pay rate, hours, or health or safety conditions, company representatives would simply point the finger at the contractor, freeing the large corporate entities from any responsibility while reducing capital outlays to a bare minimum. Another obvious point of contention was the operator's practice of appointing checkweighmen. The checkweighmen, whose job was to weigh the loaded cars of coal, frequently cheated the contractor and his workers by adjusting the weight to company-imposed maximums and ignoring actual output.17

Blacks, who in 1930 constituted 62 percent of the coal miners in Jefferson County, suffered most under the prevailing system. Not only were blacks paid less than whites for the same work, but operators tended to use wider screens for coal mined by blacks, effectively reducing the tonnage for which they were credited. Nor were black miners paid for “dead work,” such as post- and pre-production cleanup, for which their white co-workers were paid. Occupational discrimination also reduced wages and placed a ceiling on job mobility. While white workers held exclusive rights to positions such as contractor or machine operator, blacks rarely rose above coal loading, pick mining, and other unskilled, often seasonal, occupations.18

Despite William Mitch's commitment to interracial solidarity, UMWA leaders generally ignored the coal industry's peculiar forms of racial discrimination and exploitation. Communist miners, therefore, gained a small following within the union by protesting racial discrimination within the industry as well as in the union. The Party abandoned the dual-union policies characteristic of the NMU and created “rank-and-file committees” within the UMWA. These committees raised issues that UMWA leaders refused to address, including barriers to black occupational mobility and the lack of black participation in the union's bureaucracy. And while the UMWA received praise from most black and white liberal observers, not to mention a few rank-and-file Communists, for its unequivocal racial egalitarianism, most local and national Communist leaders believed the union did not go far enough. Even the UMWA's longstanding policy of preserving the offices of vice-president and recording secretary for blacks, and president and executive secretary for whites, was attacked by a few Party theoreticians as another form of segregation because it limited blacks to designated positions and kept them from holding the union's top offices. One Communist writer, social scientist and novelist Myra Page, discovered during her tour of Alabama's coal mines in 1934 that blacks comprised only one-third of state convention delegates, yet they made up the majority of union membership. As one white UMWA official told her, “We give niggers one out of three on committees, keep ‘em satisfied and white man control [sic].” Nevertheless, most black Communists who toiled in the mines for a living were not as quick to criticize the union, especially since blacks served as treasurers in several locals, and in a few cases became checkweighmen once workers won the right to elect their own.19

The rank-and-file committees continued to push UMWA leadership to adopt more egalitarian racial policies, but early in 1934 another issue caused even greater internal dissension within the union: William Mitch accepted the NRA's minimum wage code, which paid Southern workers less than Northern workers. Southern coal operators rationalized lower wages by arguing that unusually high freight rates and the lower grade of Alabama coal pushed production costs relatively high. The regional wage differential sparked a militant, Communist-led opposition movement within the UMWA only months after its resuscitation, culminating in an unauthorized strike in February. Defying the decisions of the NRA Regional Labor Board and the UMWA, an estimated fifteen to twenty thousand miners walked off their jobs demanding higher wages, union recognition, and the abolition of the wage differential. When Mitch ordered the miners back to work, the Communist unit at the Lewisburg mine responded by calling for greater rank-and-file control and adding demands that drew attention to the most exploitative aspects of the miner's life and work. Party leaflets littered the mining camps advocating, among other things, a basic day rate of one dollar above the prevailing NRA code, a minimum tonnage rate, equal work and unfettered occupational mobility for black miners, an eight-hour day, free transportation to and from work, and a drastic reduction in commissary prices. Mitch temporarily settled the strike on March 16, but the strikers had to agree to limit union recognition to a voluntary checkoff system, freeze all strikes until April 1, 1935, and accept prevailing wages. Nevertheless, the negotiations resulted in two significant concessions—the abolition of the contracting system and the right of workers to elect checkweighmen.20

The uneasy peace between coal operators and the UMWA did not last very long. In a surprising move, the NRA raised the minimum wage for Southern bituminous coal miners by $1.20, nearly equalizing the Northern-based minimum, but following a federal injunction obtained by Alabama coal operators, the code was reduced to a forty-cent raise. Consequently, the operators rejected the modified code as well, thus provoking some fourteen thousand coal miners to walk off their jobs in April against William Mitch's wishes. Communists convinced workers at Docena and Hamilton Slope mines to leave their jobs, organized pickets at the TCI-owned Wylam and Edgewater mines, and led a group of steel workers to Republic Steel's captive coal mines and persuaded miners there to join the strike. In addition to protesting the wage differential, the Party called for an end to the operators’ practice of deducting relief payments and back rent from the miners’ paychecks, thus drawing attention to the links between housing and welfare policies and workers’ dependence on the company. The April walkout marked the height of Party influence in the Alabama coal fields—a fact that did not escape the attention of William Mitch. He not only blamed “radical elements” for instigating the unauthorized strike but encouraged UMWA officials to work with company police to keep Communists out of the mines. The strike was eventually broken and most of the strikers either returned to work or were promptly fired.21

The Party exercised even greater influence within the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, a union comprised mainly of iron ore miners and a handful of steel workers. Originally an outgrowth of the Western Federation of Miners, a militant union that helped launch the IWW in 1905, Mine Mill developed a national reputation as a radical, left-wing union during the 1930s. The prominent role Communists played in Mine Mill can be partially attributed to the fact that, in 1933, 80 percent of the district's ore miners, and an even greater percentage of the union, were black. Indeed, black workers—many of whom had gained experience in the Communist-led unemployed movement—held the majority of middle- and low-level leadership positions within the union. George Lemley, whose father was an organizer for Mine Mill, recalled, “When the union went in, some blacks thought they would rule the company. Everything will go our way.”22

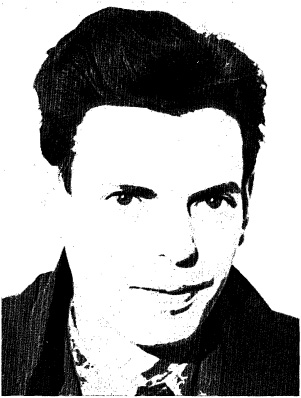

“Meat for the Buzzards!” Cartoon depicting the National Recovery Act's role in undercutting Alabama coal miners (Daily Worker, 1934)

When Jim Lipscomb, a Bessemer lawyer and former miner blacklisted for union activities, initiated Mine Mill's organizing drive in 1933, the prevalence of black workers and the union's egalitarian goals gave the movement an air of civil rights activism. Union meetings were held in the woods, in sympathetic black churches, or anywhere else activists could meet without molestation. Company police used violence and intimidation in an effort to crush Mine Mill before it could establish a following, but when these tactics failed, officials exploited racial animosities. TCI created a company union, the ERP, which used racist and anti-Communist slogans to appeal to white workers. Mine Mill quickly earned the nom de guerre “nigger union,” and white workers who repudiated the ERP were labeled “communists” and “nigger lovers.” Officials also cut social welfare programs and enforced segregation codes much more stringently than before.23

In addition to building rank-and-file committees, some Communists were elected to leadership positions within their local. As one Mine Mill organizer explained in 1934, the Party had “even greater influence and stronger organization among the ore miners” than any other industry. Communists were frequently identified openly at union meetings, and in many cases, earned the endearment of black union members because of the Party's commitment to racial equality and civil rights. High-ranking white Mine Mill officials, on the other hand, shared mainstream labor leaders’ disdain for Communists. Leaders of the Brighton local, for example, endorsed a resolution that read, “We are opposed to and do not tolerate Communism, and will not accept the application of any man for membership, who is tainted with its poison.” A few months later, the president of Bessemer's Local 1 expelled white Communist John Davis and two black Communists, Nathan Strong and Ed Sears, solely because of their political affiliations.24

Prodded by the rank-and-file committees, local Mine Mill leaders issued a strike call in May 1934 to ore miners at TCI, Republic Steel Corporation, the Sloss-Sheffield Iron and Steel Company, and the Woodward Iron Company demanding higher wages, shorter hours, and union recognition. The companies refused to arbitrate and responded by firing and evicting dozens of union members. Violence between strikers and company police left two strike breakers dead and at least nine workers wounded. Despite the intervention of state troops, bombs exploded and gunfire was exchanged intermittently throughout most of the summer.25

During the strike, Communists devoted most of their energy to publicizing antiunion violence in the ore mines, fighting evictions, and securing relief for the strikers. Communists created miniature unemployed committees within Mine Mill that were instrumental in preventing several evictions, fighting for the strikers’ right to receive public relief, and maintaining picket lines. In Bessemer, Clyde Johnson obtained much needed assistance for striking miners from the city's relief authorities and secured crucial support from the otherwise conservative Bessemer Central Trades and Labor Council.26

With the intervention of Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, an agreement between Mine Mill and TCI was finally reached on June 27, though it was hardly a victory for the union. Mine Mill remained unrecognized, and wages increased only slightly. The Communists not only found the bargain unacceptable but pointed to blatant examples of antiunion discrimination and numerous instances of company noncompliance with the agreement. At the Raimund mine, for example, only 60 percent of the strikers were rehired while the other 40 percent were summarily fired and evicted. Party units at Muscoda mine adopted the slogan, “No Union Miners Move—All Scabs off Red Mountain,” and Communists active at a Sloss-Sheffield mine threatened to lead an unauthorized strike over the same issue.27

Mine Mill also led a small strike of steel workers at Republic Steel Corporation. Urged on by the Communist Party unit in Republic's East Thomas blast furnace, an estimated four hundred workers walked off their jobs in April and demanded a flat 20 percent wage increase and union recognition. A handful of Communists in Mine Mill attempted to extend the strike by marching on Sayreton coal mine in order to persuade the captive miners to join them, but they were intercepted by a squadron of company police. Vance Houdlitch, a young white steel worker, was gunned down, and Communist Mark Ellis was badly beaten. The Republic strikers eventually won an employee representation election conducted by the Atlanta Regional (NRA) Labor Board one month later; but the company would not recognize the union, and the NRA did not have the power to enforce the ruling. Consequently, the Thomas blast furnace workers remained on strike for over a year, receiving far more criticism than support from organized labor.28

Besides some feeble attempts on the part of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, the dying craft union that had been temporarily reinvigorated by the NRA, the steel industry in the Birmingham district remained unorganized until the CIO came into being a few years later. Through the use of lockouts, company unions, intimidation, and the exploitation of racial divisions within the labor force, Birmingham's steel industry effectively hindered labor organization in the mills. The Communists placed much of the blame squarely on the shoulders of Amalgamated's local leadership, particularly its president, W. H. Crawford. Crawford opposed rank-and-file sentiment to join the 1934 strike wave, denounced the Republic Steel strike, and all but ignored black workers. Communist labor organizers agreed that the union's success depended on black workers who, in 1930, made up 47 percent of the labor force in Birmingham's steel and iron industries.29

Rather than wait for a policy change in Amalgamated, Communists sought to organize metal workers autonomously by establishing federal locals chartered through the AFL's national headquarters. Clyde Johnson was instrumental in forming federal locals in four shops, three of which signed collective agreements with their employers. At the Virginia Bridge and Iron Company, Johnson struck a bargain with employers only after leading a dramatic one-day walkout and plant shutdown. At the Central Foundry in Tuscaloosa, Communists chartered a federal local with over five hundred workers after the segregated International Molders Union denied membership to black and unskilled white labor.30

The Communists certainly made their presence felt among miners and steel workers during the 1934 strike wave. Yet their actual contribution remained essentially behind the scenes, partly because most union Communists were black, unskilled, rank-and-file workers. Although individuals such as Henry O. Mayfield, Joe Howard, and Ebb Cox would rise within the ranks of the CIO during the late 1930s, the majority of blacks—Communist or not—had few opportunities for advancement within the labor movement. Another, often overlooked reason for the Party's behind-the-scenes role in the 1934 strikes stems from the fact that many rank-and-file organizers were the wives and daughters of black industrial workers, and/or they were women who had joined the CP through the neighborhood relief committees. With the open encouragement of the rank-and-file committees, women's auxiliaries were formed in virtually all working-class communities. Frequently led by Communists or ILD activists, the women's auxiliaries sometimes rivaled union locals in membership as well as in their strident advocacy of labor organization. The growth and radicalization of the women's auxiliaries were certainly linked to the increasing work load of black women in the company-controlled communities—induced, of course, by cutbacks in wages and hours. Henry O. Mayfield recalled that whenever union members failed to recruit a recalcitrant worker, the women “would send a committee to talk with the worker's wife or the worker and they would always win their point.” One white coal miner suggested that the presence of black women ensured the union's success. “Not a scab gets by ‘em,” he observed. “Just let one of their race try it. Why, their women folks handle him!” Workers’ wives used a number of methods to “handle” their menfolk, such as withholding labor and sex, which might be described as a kind of “domestic strike.” In a telling commentary, one ex-ore miner explains: “Womens can just about rule mens, you know things like that, to keep them from going back to the company or something another like that. ‘Cause all of them was union. A man got a wife, and if he going back to the company [and] she didn't want him to go, then she'll say, ‘If you go back, then me and you ain't going to be husband and wife no more.’” The women's auxiliaries also provided crucial material support during strikes. Ironically, the gardens women cultivated with the encouragement of the company, ultimately intended to offset wage reductions, became a source of strikers’ relief. Coal miner Cleatus Burns remembers several strikes during which union members “would give sweet potatoes, corn, and . . . anything out the garden that they had.” When the gardens proved inadequate, according to Mayfield, “the women would organize into groups and take baskets and go into stores asking for food for needy families.”31

The disturbances in the coal, iron, and steel industries represented merely the apex of a year-long labor revolt. In February, nearly 1,500 Birmingham laundry workers struck for wage increases; 250 packinghouse workers walked off their jobs in May; and wildcat strikes, some of which had been coordinated by Communist organizers, exploded on several New Deal relief projects. Alabama also felt the impact of the West Coast waterfront strikes, which drew a few hundred Mobile longshoremen into the fray, and some 23,000 Alabama textile workers joined the national textile strike. In all, the state experienced at least 45 strikes involving 84,228 workers during the tumultuous year of 1934.32

In spite of the Party's emphasis on industrial unionism, Alabama Communists did not entirely withdraw from organizing relief workers and the unemployed. In Tarrant City, an industrial suburb of Birmingham, the Party founded the RWL in 1934. Led by white Communist C. Dave Smith, a veteran labor organizer and dynamic speaker who, according to Clyde Johnson, “had guts and was quick with his fists,” the RWL was quite popular among Tarrant City workers and even enjoyed support from Mayor Roy Ingram. Mainly through the work of Smith, Clyde Johnson, and local Communists Penny Parker and Jesse Owens, Tarrant City became the Party's strongest base of white working-class support.33

Communists tried to organize black relief workers in the CCC, a New Deal agency created to relieve poverty and train youth in forest conservation work. From the outset, protests over the working and living conditions were commonplace in the segregated camps, and several CCC workers were placed “under observation” for allegedly spreading “damaging propaganda.” In February 1934, a few YCL activists organized a strike of about two hundred black CCC workers in a camp near Tuscaloosa. What began as a peaceful protest erupted into violence when state troops intervened and strikers retaliated with a barrage of bricks. Once the fighting subsided, CCC authorities promptly fired about 160 workers and had YCL activist Boykin Queenie, the strike's leader, arrested. The Communist Party, along with the discharged strikers, issued a statement demanding Queenie's immediate release.34

Communists played no significant part in the Alabama textile strike. Because the Party had not organized in Huntsville, the heart of the state's textile industry, the district committee sent “flying squadrons” of organizers that drove through mill towns at night and littered the area with leaflets. Aside from sloganeering, the Party made no sustained effort to organize the Alabama textile mills. Besides, its predominantly black cadre would have had a difficult time trying to convince white, often racist textile workers to cast their lot with the Communists. Not surprisingly, the Communists could only claim “considerable influence among the Negro textile workers” in Birmingham.35

On the Gulf Coast, the Party's diminutive role can be attributed to its size and to workers’ reluctance to join the waterfront strike. Communists only began organizing in Mobile in August 1934, two months before the strike. In response to the West Coast waterfront strike, the Communist-led MWIU created a Joint Strike Preparations Committee with support from the ISU and a few active members of the nearly defunct IWW. On the eve of the walkout, the committee convinced the ILA in Mobile to join the strike, raising the total number of strikers to a minuscule four hundred workers, but after three days the ISU and ILA called their members back to work. William McGee, president of the MWIU in Mobile, criticized the unions’ turnabout on the strike decision and organized a mass rally of about one hundred black and white seamen, but police dispersed the crowd before the rally began.36

Although the Party's role in the 1934 strike wave was uneven and often insignificant, opponents attributed practically every action associated with worker rebellion to the CP. Birmingham newspapers carried headlines such as “Strike Moves Near Climax,” “Reds Linked with Violence,” and “Outbreak Believed Work of Agitators.”37 Ironically, Daily Worker reports confirmed the fears of many Birmingham residents by exaggerating the Party's role and, in an odd way, by attracting radical artists and intellectuals from outside Alabama. The outsiders’ brief forays to Birmingham—which usually included a day with the SCU—resembled artists’ sojourns to the front during the Spanish Civil War. They wanted to witness firsthand the heroism of Dixie's interracial vanguard, and those who experienced police repression or harassment wore their stripes proudly. Among them were luminaries such as playwright and novelist John Howard Lawson, authors Jack Conroy, Myra Page, and Grace Lumpkin, and visual artist Paul Weller—most of whom used the experiences or knowledge they obtained in Alabama in their work.38

The Party's strong showing at the 1934 May Day demonstration, which coincided with the most intense period of strike activity, fueled the notion that Communists provoked the unrest. The Party's first major rally since the May Day debacle of the previous year attracted over five thousand people to Capitol Park, despite the city commission's last-minute revocation of a parade permit. Police prepared for the event by mounting machine guns atop the Jefferson County jail and enlisting the support of approximately fifteen hundred White Legionnaires. Before the speakers could address the crowd, police officers and Legionnaires began beating and arresting protesters.39

Under orders from Birmingham police chief E. L. Hollums, officers launched a wave of retaliatory raids several days after the demonstration, jailing nearly a dozen Communists on charges ranging from vagrancy to criminal anarchy. The first wave of arrestees, comprised primarily of local leaders and known visitors, included Louise Thompson, a black International Workers’ Order representative visiting from New York. The incarceration of renowned radical playwright John Howard Lawson, who was charged with libel for his Daily Worker article describing the arrests and trials of six Birmingham Communist leaders, attracted national attention to civil liberties violations in Birmingham. The wave of repression even piqued the ACLU's interest, particularly after Birmingham's Western Union office manager refused to transmit two dispatches from a Daily Worker correspondent because he found them to be “highly inflammatory.”40

While the sensationalist claims of the press were more invention than reality, they had the effect of promoting the Communist Party from mere nuisance to Birmingham's number one public enemy in the minds of many. For their growing popularity the Communists had to bear the brunt of antilabor violence. The “Red Squad,” a special unit of the Birmingham police department headed by detective J. T. Moser, became a beehive of activity. Although police had both the 1930 criminal anarchy ordinance and vagrancy laws at their disposal, the Red Squad more commonly invoked section 4902 of the Birmingham criminal code because it allowed police, without a warrant, to arrest and detain anyone for up to seventy-two hours without charge. Section 4902 was used to obtain information and/or to intimidate activists without having to go to court.41 Clyde Johnson, who had been arrested by the Birmingham police force at least three times in 1934, was severely beaten while being held incommunicado.

At first I didn't think they were interested in me answering questions because they'd ask a question, and if I didn't respond quickly enough . . . they started beating the living hell out of me, on my head. And then they'd make me put my hands on the table, and they started pounding at my hands. They broke a couple of fingers. They kept at this and I didn't answer. I decided they were going to kill me. ... I went unconscious, and they threw water at me, and I went through it some more. [When] they picked me up I was barely able to walk.42

Black Communist Helen Longs was arrested for distributing leaflets explaining the Party's election platform. Although the charge was eventually reduced to “disorderly conduct,” the police detained her under section 4902 and proceeded with their peculiar form of interrogation:

Three of them had rubber hoses, one had [a] strap . . . and one had a blackjack. The biggest one of the men tried to make me lie down but I wouldn't. Then they hit me with the hose and with the strap with such force as almost to knock me down but when I didn't fall the biggest man finally grabbed me and threw me down. . . . While they had me on the floor one of them would beat me until he got tired and then another would start in. Then two or three would beat me at the same time until I nearly lost consciousness.43

The Red Squad stepped up its activities during the summer, jailing dozens of Communists charged with violating the criminal anarchy ordinance. In July, police arrested Israel Berlin for possessing Party literature, and a few days later he was jailed again, along with Communists John Beidel and Fred Keith, when police seized the entire August edition of the Southern Worker. Editor Elizabeth Lawson retaliated by putting out a special six-page edition of the Southern Worker and sending a complimentary copy to police chief Hollums. In August, police raided the home of sixty-six-year-old Addie Adkins and discovered twenty-five thousand leaflets appealing to workers to support the textile strike. Adkins was arrested and charged with distributing literature “advocating overthrow of the government by force.” In nearly all of these cases, however, the charges were dismissed by judges who ruled that Party literature did not violate the criminal anarchy ordinance.44

Frustrated by the criminal anarchy ordinance's ineffectiveness, police chief Hollums and city commissioner W. O. Downs promoted much stronger anti-Communist legislation. In May the commissioner drafted the infamous “Downs literature ordinance,” which made it unlawful to possess one or more copies of “radical” literature, defined to include any antiwar or antifascist material, labor publications, and liberal journals such as the New Republic and the Nation. The maximum sentence for violating the ordinance was six months in jail plus a fine of $100. The Birmingham City Commission adopted the ordinance in October, and the city council of Bessemer passed a similar antisedition law one month later.45

Although AFL leaders were well aware that antisedition laws could be used against organized labor, they did not protest the legislation. On the contrary, the Birmingham and Bessemer trades councils not only championed the new ordinances but called for even stronger measures. Robert Moore, president of the ASFL, felt the Downs ordinance still was not restrictive enough to deal with the threat of Communism. “We have no adequate laws in Alabama,” he announced, “to meet the constantly increasing threat from this source, but we can oust every known Communist from within the ranks of organized labor, and we propose to do just that.” W. O. Hare, secretary of the ASFL, followed Moore's advice and attempted to expel Communists and “questionable characters” from the federation.46

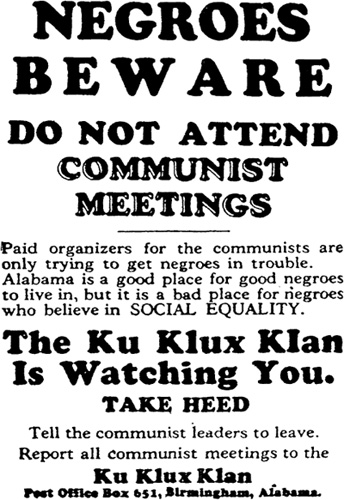

With the passage of the Downs ordinance the number of arrests rose dramatically, but as with the criminal anarchy ordinance preceding it, convictions were few and far between. Of sixty arrests in less than a year, only three resulted in convictions under the new law.47 Where due process failed, extralegal terrorist organizations succeeded. The White Legion directed virtually all of its energies toward fighting Communism, from distributing propaganda to burning crosses on the lawns of white Tarrant City Communists. In Birmingham, the Klan which had declined substantially in the late 1920s, rode the crest of antilabor and anti-Communist sentiment in 1934. In that same year, forty-four new Klaverns were organized in northern Alabama alone, and a local fascist movement affiliated with the Klan began publishing the Alabama Black Shirt. The Klan's rebirth was signaled by the appearance of thousands of leaflets warning Birmingham's blacks to stay clear of the Communists.48

The parades, literature, and other symbolic gestures were intended to intimidate activists as well as to build support among whites, but these public displays of white supremacy failed to silence Alabama radicals. Indeed, black ILD organizers occasionally responded with their own leaflets, such as the one warning: “KKK! The Workers Are Watching You!!” The vigilantes’ real influence lay in extralegal acts of violence, usually perpetrated with the assistance of local law enforcement agencies. The number of vigilante assaults on Communists and suspected Communists rose rapidly during the strike wave and continued well into 1935. In the aftermath of the ore miners’ strike, Clyde Johnson survived at least three assassination attempts. Black Communist Steve Simmons suffered a near-fatal beating at the hands of Klansmen in North Birmingham, and a few months later his black comrade in Bessemer, Saul Davis, was kidnapped by a gang of white TCI employees, stripped bare, and flogged for several hours. These examples represent only a fraction of the antiradical terror that pervaded the Birmingham district in 1934.49

As 1934 came to a close, district organizer Nat Ross and secretary Ted Wellman felt the time had come to take stock of the past in order to chart a new direction for the future. Wellman observed in a Daily Worker article that the Communists’ role in the strikes, compounded by the fact that they had suffered an inordinate amount of retaliatory violence, earned them the admiration and support of many industrial workers. He even admitted that Birmingham's working class “in many cases pushed the Party members into activity by asking for leaflets, and for information about meetings and activities.” Yet, in the Party's theoretical journals and internal organs, Wellman and Ross were far less effusive with their praise. Both submitted reports criticizing the Birmingham cadre for failing to build mine and shop units in the most important centers of industry and for expending all their energy on organizing the strikes instead of recruiting and educating industrial workers. In Nat Ross's words, they “did not sufficiently explain the connection between the struggle against the differential wage and the struggle of the share-croppers, and between the struggle for the freedom of the Scottsboro Boys and the whole fight for the right to self-determination in the Black Belt.” All writers agreed, however, that the level of repression hindered the Party's work.50

Ironically, the proliferation of antiradical violence in 1934 seemed to act as a catalyst for the Party's growth. Like many others who joined in

Anti-Communist handbill distributed by the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham in the 1930s (Labor Defender)

1934, Jesse G. Owens, a onetime Socialist from Tarrant City, interpreted the violence as proof that the Communists “must have something that was for the good of the working class.” According to Party sources, three hundred new members joined during the intense six-week period of labor activity beginning in April 1934, and by May the Communists claimed one thousand in the Birmingham district alone while the ILD's ranks swelled to three thousand.51 More significant than the numbers, however, is the fact that violence compelled local Communists to make antiradical repression and the denial of civil liberties a central issue on their agenda. The emphasis on police repression and violence was not only evident in the assessments offered by Nat Ross and Ted Wellman, but subtle changes in the Party's entire program became apparent during the 1934 election campaign. As in 1933, the Party ran candidates associated with organized labor, but the issue of civil liberties took precedence over everything else on the Party's platform. Insisting that the KKK, the White Legion, and other “armed fascist bands” be outlawed, the Communists held a demonstration in front of the Birmingham courthouse to demand the right to vote without any restrictions whatsoever. When the city commission turned down their application for a permit to hold an election rally in Capitol Park, the Communists organized several smaller rallies “in the naborhoods [sic] and sections of the city ... in order to avoid police and fascist violence.” The right of free speech and assembly became a campaign priority, articulated as a basic right denied all working people: “The Communist party will grow stronger every day and will soon TAKE ITS CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT to speak to the people openly on the streets in the public places of the city.”52

While it is impossible to accurately measure the Party's influence in the labor movement, it is clear that the Communists’ impact was far greater than their numbers indicate. They operated as the proverbial gadflies, criticizing AFL policies; popularizing strikes through publications, leaflets, and pickets; and convincing small groups of workers, including a handful of whites, of the virtues of socialism. Indeed, the Communist-led rank-and-file committees were the only organized voices within the Alabama labor movement to consistently fight against racial discrimination and to build alliances between strikers in different industries. But the more they asserted themselves in the 1934 strike wave, the greater the intensity of antiradical violence and the more difficult it became for them to work openly. Unlike the neighborhood relief committees or the unemployed councils, which were organized and run by Communists, the labor movement's relationship to the Party was ambivalent, to say the least. Surrounded by hostile trade union leaders, Communists had to perform the unenviable task of building a base of support while operating as outsiders.

Their difficulties were compounded by the fact that they were not merely anonymous outsiders, but outsiders with a volatile reputation. Their activities in the courtrooms and on the streets on behalf of poor black men accused of rape and other assorted crimes followed the Communists into the workplace and the relief offices. In a word, Alabama Communists operated under the shadow of Scottsboro—a shadow that generated as much vicious hatred as unqualified respect. It is to this shadow that we shall now turn.