War fever during the months after Sumter overrode sober reflections on the purpose of the fighting. Most people on both sides took for granted the purpose and justice of their cause. Yankees believed that they battled for flag and country. "We must fight now, not because we want to subjugate the South . . . but because we must," declared a Republican newspaper in Indianapolis. "The Nation has been defied. The National Government has been assailed. If either can be done with impunity . . . we are not a Nation, and our Government is a sham." The Chicago Journal proclaimed that the South had "outraged the Constitution, set at defiance all law, and trampled under foot that flag which has been the glorious and consecrated symbol of American Liberty." Nor did northern Democratic editors fall behind their Republican rivals in patriotism. "We were born and bred under the stars and stripes," wrote a Pittsburgh Democrat. Although the South may have had just grievances against Republicans, "when the South becomes an enemy to the American system of government . . . and fires upon the flag . . . our influence goes for that flag, no matter whether a Republican or a Democrat holds it."1

1. Indianapolis Daily Journal, April 27, 1861, Chicago Daily Journal, April 17, 1861, Pittsburgh Post, April 15, 1861, all quoted from Howard C. Perkins, ed., Northern Editorials on Secession, 2 vols. (New York, 1942), 814, 808, 739.

Scholars who have examined thousands of letters and diaries written by Union soldiers found them expressing similar motives; "fighting to maintain the best government on earth" was a common phrase. It was a "grate strugle for the Union, Constitution, and law," wrote a New Jersey soldier. "Our glorious institutions are likely to be destroyed. . . . We will be held responsible before God if we don't do our part in helping to transmit this boon of civil & religious liberty down to succeeding generations." A midwestern recruit enlisted as "a duty I owe to my country and to my children to do what I can to preserve this government as I shudder to think what is ahead for them if this government should be overthrown." Americans of 1861 felt responsible to their forebears as well as to God and posterity. "I know . . . how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and sufferings of the Revolution," wrote a New England private to his wife on the eve of the first battle of Bull Run (Manassas). "I am willing—perfectly willing—to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt."2

One of Lincoln's qualities of greatness as president was his ability to articulate these war aims in pithy prose. "Our popular government has often been called an experiment," Lincoln told Congress on July 4, 1861. "Two points in it, our people have already settled—the successful establishing, and the successful administering of it. One still remains—its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it. . . . This issue embraces more than the fate of these United States. It presents to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy . . . can or cannot, maintain its territorial integrity, against its own domestic foes."3

The flag, the Union, the Constitution, and democracy—all were symbols or abstractions, but nonetheless powerful enough to evoke a willingness to fight and die for them. Southerners also fought for abstractions

2. Wiley, Billy Yank, 40; New Jersey and midwestern soldiers quoted in Randall Clair Jimerson, "A People Divided: The Civil War Interpreted by Participants," Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1977, pp. 38–39; New England soldier quoted in William C. Davis, Battle at Bull Run (Garden City, 1977), 91–92. Two other studies contain numerous quotations from soldiers' letters making the same point: Reid Mitchell, "The Civil War Soldier: Ideology and Experience," Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 1985; and Earl J. Hess, "Liberty and Self-Control: Republican Values in the Civil War North," Ph.D. dissertation, Purdue University, 1986.

3. CWL, IV, 439, 426.

—state sovereignty, the right of secession, the Constitution as they interpreted it, the concept of a southern "nation" different from the American nation whose values had been corrupted by Yankees. "Thank God! we have a country at last," said Mississippian L. Q. C. Lamar in June 1861, a country "to live for, to pray for, to fight for, and if necessary, to die for." "Submission to the yoke of depotism," agreed army recruits from North Carolina and Georgia, would mean "servile subjugation and ruin." Another North Carolinian was "willing to give up my life in defence of my Home and Kindred. I had rather be dead than see the Yanks rule this country." He got his wish—at Gettysburg.4

Although southerners later bridled at the official northern name for the conflict—"The War of the Rebellion"—many of them proudly wore the label of rebel during the war itself. A New Orleans poet wrote these words a month after Sumter:

Yes, call them rebels! 'tis the name

Their patriot fathers bore,

And by such deeds they'll hallow it,

As they have done before.

Jefferson Davis said repeatedly that the South was fighting for the same "sacred right of self-government" that the revolutionary fathers had fought for. In his first message to Congress after the fall of Sumter, Davis proclaimed that the Confederacy would "seek no conquest, no aggrandizement, no concession of any kind from the States with which we were lately confederated; all we ask is to be let alone."5

Both sides believed they were fighting to preserve the heritage of republican liberty; but Davis's last phrase ("all we ask is to be let alone") specified the most immediate, tangible Confederate war aim: defense against invasion. Regarding Union soldiers as vandals bent on plundering the South and liberating the slaves, many southerners literally believed they were fighting to defend home, hearth, wives, and sisters. "Our men must prevail in combat, or lose their property, country, freedom, everything," wrote a southern diarist. "On the other hand, the enemy, in yielding the contest, may retire into their own country, and possess everything they enjoyed before the war began." A young English immigrant to Arkansas enlisted in the army after he was swept off his

4. Lamar quoted in E. Merton Coulter, The Confederate States of America 1861–1865; (Baton Rouge, 1950), 57; soldiers quoted in Jimerson, "A People Divided," 20, 23.

5. Coulter, Confederate States, 60; Rowland, Davis, V, 84.

feet by a recruitment meeting. He later wrote that his southern friends "said they would welcome a bloody grave rather than survive to see the proud foe violating their altars and their hearths." Southern women brought irresistible pressure on men to enlist. "If every man did not hasten to battle, they vowed they would themselves rush out and meet the Yankee vandals. In a land where women are worshipped by the men, such language made them war-mad."6 A Virginian was avid "to be in the front rank of the first brigade that marches against the invading foe who now pollute the sacred soil of my beloved native state with their unholy tread." A Confederate soldier captured early in the war put it more simply. His tattered homespun uniform and even more homespun speech made it clear that he was not a member of the planter class. His captors asked why he, a nonslaveholder, was fighting to uphold slavery. He replied: "I'm fighting because you're down here."7

For this soldier, as for many other southerners, the war was not about slavery. But without slavery there would have been no Black Republicans to threaten the South's way of life, no special southern civilization to defend against Yankee invasion. This paradox plagued southern efforts to define their war aims. In particular, slavery handicapped Confederate foreign policy. The first southern commissioners to Britain reported in May 1861 that "the public mind here is entirely opposed to the Government of the Confederate States of America on the question of slavery. . . . The sincerity and universality of this feeling embarrass the Government in dealing with the question of our recognition."8 In their explanations of war aims, therefore, Confederates rarely mentioned slavery except obliquely in reference to northern violations of southern rights. Rather, they portrayed the South as fighting for liberty and self-government—blithely unmindful of Samuel Johnson's piquant question about an earlier generation of American rebels: "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?"

For reasons of their own most northerners initially agreed that the war had nothing to do with slavery. In his message to the special session

6. Jones, War Clerk's Diary (Miers), 181; The Autobiography of Sir Henry M. Stanley, ed. Dorothy Stanley (Boston and London, 1909), 165.

7. Thomas B. Webber to his mother, June 15, 1861, Civil War Times Illustrated Collection, United States Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pa.; Foote, Civil War, I, 65.

8. William L. Yancey and A. Dudley Mann to Robert Toombs, May 21, 1861, in James D. Richardson, comp., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, 2 vols. (Nashville, 1906), II, 37.

of Congress on July 4, 1861, Lincoln reaffirmed that he had "no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists." The Constitution protected slavery in those states; the Lincoln administration fought the war on the theory that secession was unconstitutional and therefore the southern states still lived under the Constitution. Congress concurred. On July 22 and 25 the House and Senate passed similar resolutions sponsored by John J. Crittenden of Kentucky and Andrew Johnson of Tennessee affirming that the United States fought with no intention "of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions of [the seceded] States" but only "to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and to preserve the Union with all the dignity, equality, and rights of the several States unimpaired."9

Republicans would soon change their minds about this. But in July 1861 even radicals who hoped that the war would destroy slavery voted for the Crittenden-Johnson resolutions (though three radicals voted No and two dozen abstained). Most abolitionists at first also refrained from open criticism of the government's neutral course toward slavery. Assuming that the "death-grapple with the Southern slave oligarchy" must eventually destroy slavery itself, William Lloyd Garrison advised fellow abolitionists in April 1861 to " 'stand still, and see the salvation of God' rather than attempt to add anything to the general commotion."10

A concern for northern unity underlay this decision to keep a low profile on the slavery issue. Lincoln had won less than half of the popular vote in the Union states (including the border states) in 1860. Some of those who had voted for him, as well as all who had voted for his opponents, would have refused to countenance an antislavery war in 1861. By the same token, an explicit avowal that the defense of slavery was a primary Confederate war aim might have proven more divisive than unifying in the South. Both sides, therefore, shoved slavery under the rug as they concentrated their energies on mobilizing eager citizen soldiers and devising strategies to use them.

The United States has usually prepared for its wars after getting into them. Never was this more true than in the Civil War. The country

9. CWL, IV, 263, 438–39; CG, 37 Cong., 1 Sess., 222–23, 258–62.

10. Garrison to Oliver Johnson, April 19, 1861, William Lloyd Garrison Papers, Boston Public Library.

was less ready for what proved to be its biggest war than for any other war in its history. In early 1861 most of the tiny 16,000-man army was scattered in seventy-nine frontier outposts west of the Mississippi. Nearly a third of its officers were resigning to go with the South. The War Department slumbered in ancient bureaucratic routine. Most of its clerks, as well as the four previous secretaries of war, had come from the South. All but one of the heads of the eight army bureaus had been in service since the War of 1812. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, seventy-four years old, suffered from dropsy and vertigo, and sometimes fell asleep during conferences. Many able young officers, frustrated by drab routine and cramped opportunities, had left the army for civilian careers. The "Winnebago Chief" reputation of Secretary of War Cameron did not augur well for his capacity to administer with efficiency and honesty the huge new war contracts in the offing.

The army had nothing resembling a general staff, no strategic plans, no program for mobilization. Although the army did have a Bureau of Topographical Engineers, it possessed few accurate maps of the South. When General Henry W. Halleck, commanding the Western Department in early 1862, wanted maps he had to buy them from a St. Louis bookstore. Only two officers had commanded as much as a brigade in combat, and both were over seventy. Most of the arms in government arsenals (including the 159,000 muskets seized by Confederate states) were old smoothbores, many of them flintlocks of antique vintage.

The navy was little better prepared for war. Of the forty-two ships in commission when Lincoln became president, most were patrolling waters thousands of miles from the United States. Fewer than a dozen warships were available for immediate service along the American coast. But there were some bright spots in the naval outlook. Although 373 of the navy's 1,554 officers and a few of its 7,600 seamen left to go with the South, the large merchant marine from which an expanded navy would draw experienced officers and sailors was overwhelmingly northern. Nearly all of the country's shipbuilding capacity was in the North. And the Navy Department, unlike the War Department, was blessed with outstanding leadership. Gideon Welles, whose long gray beard and stern countenance led Lincoln to call him Father Neptune, proved to be a capable administrator. But the real dynamism in the Navy Department came from Assistant Secretary Gustavus V. Fox, architect of the Fort Sumter expedition. Within weeks of Lincoln's proclamation of a blockade against Confederate ports on April 19, the Union navy had bought or chartered scores of merchant ships, armed them, and dispatched them to blockade duty. By the end of 1861 more than 260 warships were on duty and 100 more (including three experimental ironclads) were under construction.

The northern naval outlook appeared especially bright in contrast to the southern. The Confederacy began life with no navy and few facilities for building one. The South possessed no adequate shipyards except the captured naval yard at Norfolk, and not a single machine shop capable of building an engine large enough to power a respectable warship. While lacking material resources, however, the Confederate navy possessed striking human resources, especially Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory and Commanders Raphael Semmes and James D. Bulloch.

Mallory was a former U.S. senator from Florida with experience as chairman of the Senate naval affairs committee. Although snubbed by high Richmond society because of his penchant for women of questionable virtue, Mallory proved equal to the task of creating a navy from scratch. He bought tugboats, revenue cutters, and river steamboats to be converted into gunboats for harbor patrol. Recognizing that he could never challenge the Union navy on its own terms, Mallory decided to concentrate on a few specialized tasks that would utilize the South's limited assets to maximum advantage. He authorized the development of "torpedoes" (mines) to be planted at the mouths of harbors and rivers; by the end of the war such "infernal devices" had sunk or damaged forty-three Union warships. He encouraged the construction of "torpedo boats," small half-submerged cigar-shaped vessels carrying a contact mine on a bow-spar for attacking blockade ships. It was only one step from this concept to that of a fully submerged torpedo boat. The Confederacy sent into action the world's first combat submarine, the C.S.S. Hunley, which sank three times in trials, drowning the crew each time (including its inventor Horace Hunley) before sinking a blockade ship off Charleston in 1864 while going down itself for the fourth and last time.

Mallory knew of British and French experiments with ironclad warships. He believed that the South's best chance to break the blockade was to build and buy several of these revolutionary vessels, equip them with iron rams, and send them out to sink the wooden blockade ships. In June 1861 Mallory authorized the rebuilding of the half-destroyed U.S.S. Merrimack as the Confederacy's first ironclad, rechristened the C.S.S. Virginia. Although work proceeded slowly because of shortages, the South invested much hope in this secret weapon (which was no secret to the Federals, whose intelligence agents penetrated loose southern security). The Confederacy began converting other vessels into ironclads, but its main source for these and other large warships was expected to be British shipyards. For the sensitive task of exploiting this source, Mallory selected James D. Bulloch of Georgia.

With fourteen years' experience in the U.S. navy and eight years in commercial shipping, Bulloch knew ships as well as anyone in the South. He also possessed the tact, social graces, and business acumen needed for the job of getting warships built in a country whose neutrality laws threw up a thicket of obstacles. Arriving at Liverpool in June 1861, Bulloch quickly signed contracts for two steam/sail cruisers that eventually became the famed commerce raiders Florida and Alabama. In the fall of 1861 he bought a fast steamer, loaded it with 11,000 Enfield rifles, 400 barrels of gunpowder, several cannons, and large quantities of ammunition, took command of her himself, and ran the ship through the blockade into Savannah. The steamer was then converted into the ironclad ram C.S.S. Atlanta. Bulloch returned to England, where he continued his undercover efforts to build and buy warships. His activities prompted one enthusiastic historian to evaluate Bulloch's contributions to the Confederacy as next only to those of Robert E. Lee.11

The commerce raiders built in Britain represented an important part of Confederate naval strategy. In any war, the enemy's merchant shipping becomes fair game. The Confederates sent armed raiders to roam the oceans in search of northern vessels. At first the South depended on privateers for this activity. An ancient form of wartime piracy, privateering had been practiced with great success by Americans in the Revolution and the War of 1812. In 1861, Jefferson Davis proposed to turn this weapon against the Yankees. On April 17, Davis offered letters of marque to any southern shipowner who wished to turn privateer. About twenty such craft were soon cruising the sea lanes off the Atlantic coast, and by July they had captured two dozen prizes.

Panic seized northern merchants, whose cries forced the Union navy to divert ships from blockade duty to hunt down the "pirates." They enjoyed some success, but in doing so caused a crisis in the legal definition of the war. Refusing to recognize the Confederacy as a legitimate government, Lincoln on April 19, 1861, issued a proclamation threatening to treat captured privateer crews as pirates. By midsummer a number of such crews languished in northern jails awaiting trial. Jefferson Davis

11. Philip Van Doren Stern, When the Guns Roared: World Aspects of the American Civil War (Garden City, N.Y., 1965), 249–50.

declared that for every privateer hanged for piracy he would have a Union prisoner of war executed. The showdown came when Philadelphia courts convicted several privateer officers in the fall of 1861. Davis had lots drawn among Union prisoners of war, and the losers—including a grandson of Paul Revere—were readied for retaliatory hanging. The country was spared this eye-for-an-eye bloodbath when the Lincoln administration backed down. Its legal position was untenable, for in the same proclamation that had branded the privateers as pirates Lincoln had also imposed a blockade against the Confederacy. This had implicitly recognized the conflict as a war rather than merely a domestic insurrection. The Union government's decision on February 3, 1862, to treat captured privateer crews as prisoners of war was another step in the same direction.

By this time, Confederate privateers as such had disappeared from the seas. Their success had been short-lived, for the Union blockade made it difficult to bring prizes into southern ports, and neutral nations closed their ports to prizes. The Confederacy henceforth turned to commerce raiders—warships manned by naval personnel and designed to sink rather than to capture enemy shipping. The transition from privateering to commerce raiding began in June 1861, when the five-gun steam sloop C.S.S. Sumter evaded the blockade at the mouth of the Mississippi and headed toward the Atlantic. Her captain was Raphael Semmes of Alabama, a thirty-year veteran of the U.S. navy who now launched his career as the chief nemesis of that navy and terror of the American merchant marine. During the next six months the Sumter captured or burned eighteen vessels before Union warships finally bottled her up in the harbor at Gibraltar in January 1862. Semmes sold the Sumter to the British and made his way across Europe to England, where he took command of the C.S.S. Alabama and went on to bigger achievements.

Despite ingenuity and innovations, however, the Confederate navy could never overcome Union supremacy on the high seas or along the coasts and rivers of the South. The Confederacy's main hopes rode with its army. A people proud of their martial prowess, southerners felt confident of their ability to whip the Yankees in a fair fight—or even an unfair one. The idea that one Southron could lick ten Yankees—or at least three—really did exist in 1861. "Just throw three or four shells among those blue-bellied Yankees," said a North Carolinian in May 1861, "and they'll scatter like sheep." In southern eyes the North was a nation of shopkeepers. It mattered not that the Union's industrial capacity was many times greater than the Confederacy's. "It was not the improved arm, but the improved man, which would win the day," said Henry Wise of Virginia. "Let brave men advance with flint locks and old-fashioned bayonets, on the popinjays of Northern cities . . . and he would answer for it with his life, that the Yankees would break and run."12

Expecting a short and glorious war, southern boys rushed to join the colors before the fun was over. Even though the Confederacy had to organize a War Department and an army from the ground up, the South got an earlier start on mobilization than the North. As each state seceded, it took steps to consolidate and expand militia companies into active regiments. In theory the militia formed a ready reserve of trained citizen soldiers. But reality had never matched theory, and in recent decades the militia of most states had fallen into decay. By the 1850s the old idea of militia service as an obligation of all males had given way to the volunteer concept. Volunteer military companies with distinctive names—Tallapoosa Grays, Jasper Greens, Floyd Rifles, Lexington Wild Cats, Palmetto Guards, Fire Zouaves—sprang up in towns and cities across the country. In states that retained a militia framework, these companies were incorporated into the framework and became, in effect, the militia. The training, discipline, and equipment of these units varied widely. Many of them spent more time drinking than drilling. Even those that made a pretense of practicing military maneuvers sometimes resembled drum and bugle corps more than fighting outfits. Nevertheless, it was these volunteer companies that first answered the call for troops in both South and North.

By early spring 1861 South Carolina had five thousand men under arms, most of them besieging Fort Sumter. Other southern states were not far behind. The Confederate Congress in February created a War Department, and President Davis appointed Leroy P. Walker of Alabama as Secretary of War. Though a politician like his Union counterpart Simon Cameron, Walker had a better reputation for honesty and efficiency. More important, perhaps, Jefferson Davis himself was a West Point graduate, a combat veteran of the Mexican War, and a former secretary of war in the U.S. government. Although Davis's fussy supervision of Confederate military matters eventually led to conflict with some army officers, the president's martial expertise helped speed southern mobilization in 1861.

12. North Carolinian quoted in Nevins, War, I, 96; Wise quoted in Jones, War Clerk's Diary (Miers), 3.

On March 6 the Confederate Congress authorized an army of 100,000 volunteers for twelve months. Most of the militia regiments already organized were sworn into the Confederate army, while newly formed units scrambled for arms and equipment. At first the states, localities, and individuals rather than the Confederate government equipped these regiments. Although the South selected cadet gray as its official uniform color, each regiment initially supplied its own uniforms, so that Confederate armies were garbed in a confusing variety of clothing that defied the concept of "uniform." Cavalrymen and artillery batteries provided their own horses. Some volunteers brought their own weapons, ranging from bowie knives and Colt revolvers to shotguns and hunting rifles. Many recruits from planter families brought their slaves to wash clothes and cook for them. Volunteer companies, following the venerable militia tradition, elected their own officers (captain and lieutenants). State governors officially appointed regimental officers (colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major), but in many regiments these officers were actually elected either by the men of the whole regiment or by the officers of all the companies. In practice, the election of officers was often a pro forma ratification of the role that a prominent planter, lawyer, or other individual had taken in recruiting a company or a regiment. Sometimes a wealthy man also paid for the uniforms and equipment of a unit he had recruited. Wade Hampton of South Carolina, reputed to be the richest planter in the South, enlisted a "legion" (a regiment-size combination of infantry, cavalry, and artillery) that he armed and equipped at his own expense—and of which, not coincidentally, he became colonel.

By the time Lincoln called for 75,000 men after the fall of Sumter, the South's do-it-yourself mobilization had already enrolled 60,000 men. But these soldiers were beginning to experience the problems of logistics and supply that would plague the southern war effort to the end. Even after the accession of four upper-South states, the Confederacy had only one-ninth the industrial capacity of the Union. Northern states had manufactured 97 percent of the country's firearms in 1860, 94 percent of its cloth, 93 percent of its pig iron, and more than 90 percent of its boots and shoes. The Union had more than twice the density of railroads per square mile as the Confederacy, and several times the mileage of canals and macadamized roads. The South could produce enough food to feed itself, but the transport network, adequate at the beginning of the war to distribute this food, soon began to deteriorate because of a lack of replacement capacity. Nearly all of the rails had come from the North or from Britain; of 470 locomotives built in the United States during 1860, only nineteen had been made in the South.

The Confederate army's support services labored heroically to overcome these deficiencies. But with the exception of the Ordnance Bureau, their efforts always seemed too little and too late. The South experienced a hothouse industrialization during the war, but the resulting plant was shallow-rooted and poor in yield. Quartermaster General Abraham Myers could never supply the army with enough tents, uniforms, blankets, shoes, or horses and wagons. Consequently Johnny Reb often had to sleep in the open under a captured blanket, to wear a tattered homespun butternut uniform, and to march and fight barefoot unless he could liberate shoes from a dead or captured Yankee.

Confederate soldiers groused about this in the time-honored manner of all armies. They complained even more about food—or rather the lack of it—for which they held Commissary-General Lucius B. Northrop responsible. Civilians also damned Northrop for the shortages of food at the front, the rising prices at home, and the transportation nightmares that left produce rotting in warehouses while the army starved. Perhaps because of his peevish, opinionated manner, Northrop became "the most cussed and vilified man in the Confederacy."13 Nevertheless, Jefferson Davis kept him in office until almost the end of the war, a consequence, it was whispered, of cronyism stemming from their friendship as cadets at West Point. Northrop's unpopularity besmudged Davis when the war began to go badly for the South.

The Ordnance Bureau was the one bright spot of Confederate supply. When Josiah Gorgas accepted appointment as chief of ordnance in April 1861 he faced an apparently more hopeless task than did Myers or Northrop. The South already grew plenty of food, and the capacity to produce wagons, harness, shoes, and clothing seemed easier to develop than the industrial base to manufacture gunpowder, cannon, and rifles. No foundry in the South except the Tredegar Iron Works had the capability to manufacture heavy ordnance. There were no rifle works except small arsenals at Richmond and at Fayetteville, North Carolina, along with the captured machinery from the U.S. Armory at Harper's Ferry, which was transferred to Richmond. The du Pont plants in Delaware produced most of the country's gunpowder; the South had manufactured almost none, and this heavy, bulky product would be difficult

13. Woodward, Chesnut's Civil War, 124.

to smuggle through the tightening blockade. The principal ingredient of gunpowder, saltpeter (potassium nitrate, or "niter"), was also imported.

But Gorgas proved to be a genius at organization and improvisation. He almost literally turned plowshares into swords.14 He sent Caleb Huse to Europe to purchase all available arms and ammunition. Huse was as good at this job as James Bulloch was at his task of building Confederate warships in England. The arms and other supplies Huse sent back through the blockade were crucial to Confederate survival during the war's first year. Meanwhile Gorgas began to establish armories and foundries in several states to manufacture small arms and artillery. He created a Mining and Niter Bureau headed by Isaac M. St. John, who located limestone caves containing saltpeter in the southern Appalachians, and appealed to southern women to save the contents of chamber pots to be leached for niter. The Ordnance Bureau also built a huge gunpowder mill at Augusta, Georgia, which under the superintendency of George W. Rains began production in 1862. Ordnance officers roamed the South buying or seizing stills for their copper to make rifle percussion caps; they melted down church and plantation bells for bronze to build cannon; they gleaned southern battlefields for lead to remold into bullets and for damaged weapons to repair.

Gorgas, St. John, and Rains were unsung heroes of the Confederate war effort.15 The South suffered from deficiencies of everything else, but after the summer of 1862 it did not suffer seriously for want of ordnance—though the quality of Confederate artillery and shells was always a problem. Gorgas could write proudly in his diary on the third anniversary of his appointment: "Where three years ago we were not making a gun, a pistol nor a sabre, no shot nor shell (except at the Tredegar Works)—a pound of powder—we now make all these in quantities to meet the demands of our large armies."16

14. See Frank E. Vandiver, Ploughshares into Swords: Josiah Gorgas and Confederate Ordnance (Austin, Texas, 1952). An excellent study of the Confederacy's chief ordnance plant, the Tredegar Iron Works, is Charles B. Dew, Ironmaker to the Confederacy: Joseph R. Anderson and the Tredegar Iron Works (New Haven, 1966).

15. Unsung, because while other men were winning glory and promotion on the battlefield, these officers—without whom the battles could not have been fought— languished in lower ranks. Gorgas was not promoted to brigadier general until November 10, 1864, St. John not until February 16, 1865, and Rains ended the war as a colonel.

16. Frank E. Vandiver, ed., The Civil War Diary of General Josiah Gorgas (University, Ala., 1947), 91.

But in 1861 these achievements still lay in the future. Shortages and administrative chaos seemed to characterize the Ordnance Bureau as much as any other department of the army. In a typical report, a southern staff officer in the Shenandoah Valley wrote on May 19 that the men were "unprovided, unequipped, unsupplied with ammunition and provisions. . . . The utter confusion and ignorance presiding in the councils of the authorities . . . is without a parallel." Despite the inability to equip men already in the army, the Confederate Congress in May 1861 authorized the enlistment of up to 400,000 additional volunteers for three-year terms. Recruits came forward in such numbers that the War Department, by its own admission, had to turn away 200,000 for lack of arms and equipment. One reason for this shortage of arms was the hoarding by state governors of muskets seized from federal arsenals when the states seceded. Several governors insisted on retaining these weapons to arm regiments they kept at home (instead of sending them to the main fronts in Virginia or Tennessee) to defend state borders and guard against potential slave uprisings. This was an early manifestation of state's-rights sentiment that handicapped centralized efforts. As such it was hardly the Richmond government's fault, but soldiers in front-line armies wanted to blame somebody, and Secretary of War Walker was a natural scapegoat. "The opinion prevails throughout the army," wrote General Beauregard's aide-de-camp at Manassas on June 22, "that there is great imbecility and shameful neglect in the War Department."17 Although Beauregard's army won the battle of Manassas a month later, criticism of Walker rose to a crescendo. Many southerners believed that the only thing preventing the Confederates from going on to capture Washington after the victory was the lack of supplies and transportation for which the War Department was responsible. Harassed by criticism and overwork, Walker resigned in September and was replaced by Judah P. Benjamin, the second of the five men who eventually served in the revolving-door office of war secretary.

Walker—like his successors—was a victim of circumstances more than of his own ineptitude. The same could not be said of his counterpart in Washington. Although Simon Cameron was also swamped by the rapid

17. Nevins, War, I, 115; O.R., Ser. IV, Vol. 1, p. 497; James C. Chesnut to Mary Boykin Chesnut, June 22, in Woodward, Chesnut's Civil War, 90.

buildup of an army that exceeded the capacity of the bureaucracy to equip it, he was more deserving of personal censure than Walker.

The North started later than the South to raise an army. The Union had more than 3.5 times as many white men of military age as the Confederacy. But when adjustments are made for the disloyal, the unavailable (most men from the western territories and Pacific coast states), and for the release of white workers for the Confederate army by the existence of slavery in the South, the actual Union manpower superiority was about 2.5 to 1. From 1862 onward the Union army enjoyed approximately this superiority in numbers. But because of its earlier start in creating an army, the Confederacy in June 1861 came closer to matching the Union in mobilized manpower than at any other time in the war.

Lincoln's appeal for 75,000 ninety-day militiamen had been based on a law of 1795 providing for calling state militia into federal service. The government soon recognized that the war was likely to last more than three months and to require more than 75,000 men. On May 3, Lincoln called for 42,000 three-year army volunteers and 18,000 sailors, besides expanding the regular army by an additional 23,000 men. The president did this without congressional authorization, citing his constitutional power as commander in chief. When Congress met in July it not only retroactively sanctioned Lincoln's actions but also authorized another one million three-year volunteers. In the meantime some states had enrolled two-year volunteers (about 30,000 men), which the War Department reluctantly accepted. By early 1862 more than 700,000 men had joined the Union army. Some 90,000 of them had enlisted in the ninety-day regiments whose time had expired. But many of these men had re-enlisted in three-year regiments, and several ninety-day regiments had converted themselves into three-year units.

These varying enlistments confused contemporaries as much as they have confused historians. Indeed, the Union recruitment process, like the Confederate, was marked by enterprise and vigor at the local and state levels degenerating into confusion at the national level. Secretary of War Cameron's slipshod administrative procedures frustrated the brisk, businesslike governors. "Twenty-four hundred men in camp and less than half of them armed," Indiana's Governor Morton wrote to Cameron early in the war. "Why has there been such delay in sending arms? . . . No officer here yet to muster troops into service. Not a pound of powder or a single ball sent us, or any sort of equipment. Allow me to ask what is the cause of all this?" A few months later Ulysses S. Grant, commanding the Union base at Cairo, Illinois, voiced a typical plaint: "There is great deficiency in transportation. I have no ambulances. The clothing received has been almost universally of an inferior quality and deficient in quantity. The arms in the hands of the men are mostly the old flint-lock repaired. . . . The Quartermaster's Department has been carried on with so little funds that Government credit has become exhausted." By the end of June, Cameron was turning away offers of regiments. As Lincoln ruefully admitted in his July 4 message to Congress, "one of the greatest perplexities of the government, is to avoid receiving troops faster than it can provide for them."18

States, cities, and individuals took up the slack left by the national government. Most governors convened their legislatures, which appropriated funds to equip and supply regiments at state expense until the army could absorb them. Governors sent purchasing agents to Europe, where they competed with each other and with Confederate agents to bid up the price of the Old World's surplus arms to supply the armies of the New. The states contracted with textile mills and shoe factories for uniforms and shoes. Municipalities raised money to organize and supply "their" regiments. Voluntary associations such as the Union Defense Committee of New York sprang into existence to recruit regiments, equip them, and charter ships or trains to transport them to Washington. A group of northern physicians and women formed the United States Sanitary Commission to supplement the inadequate and outdated facilities of the Army Medical Bureau.

The earliest northern regiments, like the southern, were clad in a colorful variety of uniforms: blue from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania; gray from Wisconsin and Iowa; gray with emerald trim from Vermont; black trousers and red flannel shirts from Minnesota; and gaudy "Zouave" outfits from New York with their baggy red breeches, purple blouses, and red fezzes. The Union forces gathering in Washington looked like a circus on parade. The variety of uniforms in both Union and Confederate armies, and the similarity of some uniforms on opposite sides, caused tragic mixups in early battles when regiments mistook friends for enemies or enemies for friends. As fast as possible the northern government overcame this situation by clothing its soldiers in the standard light blue trousers and dark blue blouse of the regular army.

By the latter part of 1861 the War Department had taken over from the states the responsibility for feeding, clothing, and arming Union

18. O.R., Ser. III, Vol. 1, p. 89; Ser. I, Vol. 7, p. 442; CWL, IV, 432.

soldiers. But this process was marred by inefficiency, profiteering, and corruption. To fill contracts for hundreds of thousands of uniforms, textile manufacturers compressed the fibers of recycled woolen goods into a material called "shoddy." This noun soon became an adjective to describe uniforms that ripped after a few weeks of wear, shoes that fell apart, blankets that disintegrated, and poor workmanship in general on items necessary to equip an army of half a million men and to create its support services within a few short months. Railroads overcharged the government; some contractors sold muskets back to the army for $20 each that they had earlier bought as surplus arms at $3.50; sharp horse traders sold spavined animals to the army at outrageous prices. Simon Cameron became the target of just as well as unjust criticism of such transactions. He signed lucrative contracts without competitive bidding and gave a suspiciously large number of contracts to firms in his home state of Pennsylvania. The War Department routed a great deal of military traffic over the Northern Central Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad in which Cameron and Assistant Secretary of War Thomas Scott had direct financial interests.

The House created an investigatory committee on contracts that issued a report in mid-1862 condemning Cameron's management. By then Lincoln had long since gotten rid of Cameron by sending him to St. Petersburg as minister to Russia. The new secretary of war was Edwin M. Stanton, a hard-working, gimlet-eyed lawyer from Ohio who had served briefly as attorney general in the Buchanan administration. A former Democrat with a low opinion of Lincoln, Stanton radically revised both his politics and his opinion after taking over the war office in January 1862. He also became famous for his incorruptible efficiency and brusque rudeness toward war contractors—and toward everyone else as well.

Even before Stanton swept into the War Department with a new broom, the headlong, helter-skelter, seat-of-the pants mobilization of 1861 was just about over. The army's logistical apparatus had survived its shakedown trials and had even achieved a modicum of efficiency. The northern economy had geared up for war production on a scale that would make the Union army the best fed, most lavishly supplied army that had ever existed. Much of the credit for this belonged to Montgomery Meigs, who became quartermaster general of the army in June 1861. Meigs had graduated near the top of his West Point class and had achieved an outstanding record in the corps of engineers. He supervised a number of large projects including the building of the new Capitol dome and construction of the Potomac Aqueduct to bring water to Washington. His experience in dealing with contractors enabled him to impose some order and honesty on the chaos and corruption of early war contracts. Meigs insisted on competitive bidding whenever possible, instead of the cost-plus system favored by manufacturers who liked to inflate profits by padding costs.

Nearly everything needed by an army except weapons and food was supplied by the Quartermaster Bureau: uniforms, overcoats, shoes, knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, mess gear, blankets, tents, camp equipage, barracks, horses, mules, forage, harnesses, horseshoes and portable blacksmith shops, supply wagons, ships when the army could be supplied by water, coal or wood to fuel them, and supply depots for storage and distribution. The logistical demands of the Union army were much greater than those of its enemy. Most of the war was fought in the South where Confederate forces operated close to the source of many of their supplies. Invading northern armies, by contrast, had to maintain long supply lines of wagon trains, railroads, and port facilities. A Union army operating in enemy territory averaged one wagon for every forty men and one horse or mule (including cavalry and artillery horses) for every two or three men. A campaigning army of 100,000 men therefore required 2,500 supply wagons and at least 35,000 animals, and consumed 600 tons of supplies each day. Although in a few noted cases—Grant in the Vicksburg campaign, Sherman in his march through Georgia and the Carolinas—Union armies cut loose from their bases and lived off the country, such campaigns were the exception.

Meigs furnished these requirements in a style that made him the unsung hero of northern victory. He oversaw the spending of $1.5 billion, almost half of the direct cost of the Union war effort. He compelled field armies to abandon the large, heavy Sibley and Adams tents in favor of portable shelter tents known to Yankee soldiers as "dog tents"—and to their descendants as pup tents. The Quartermaster Bureau furnished clothing manufacturers with a series of graduated standard measurements for uniforms. This introduced a concept of "sizes" that was applied to men's civilian clothing after the war. The army's voracious demand for shoes prompted the widespread introduction of the new Blake-McKay machine for sewing uppers to soles. In these and many other ways, Meigs and his Bureau left a permanent mark on American society.

In the North as in the South, volunteer regiments retained close ties to their states. Enlisted men elected many of their officers and governors appointed the rest. Companies and even whole regiments often consisted of recruits from a single township, city, or county. Companies from neighboring towns combined to form a regiment, which received a numerical designation in chronological order of organization: the 15th Massachusetts Infantry, the 2nd Pennsylvania Cavalry, the 4th Volunteer Battery of Ohio Artillery, and so on. Ethnic affinity also formed the basis of some companies and regiments: the 69th New York was one of many Irish regiments; the 79th New York were Highland Scots complete with kilted dress uniforms; numerous regiments contained mostly men of German extraction. Sometimes brothers, cousins, or fathers and sons belonged to the same company or regiment. Localities and ethnic groups retained a strong sense of identity with "their" regiments. This helped to boost morale on both the home and fighting fronts, but it could mean sudden calamity for family or neighborhood if a regiment suffered 50 percent or more casualties in a single battle, as many did.

The normal complement of a regiment in both the Union and Confederate armies was a thousand men formed in ten companies. Within a few months, however, deaths and discharges because of sickness significantly reduced this number. Medical examinations of recruits were often superficial. A subsequent investigation of Union enlistment procedures in 1861 estimated that 25 percent of the recruits should have been rejected for medical reasons. Many of these men soon had to be invalided out of the army. Within a year of its organization a typical regiment was reduced to half or less of its original number by sickness, battle casualties, and desertions. Instead of recruiting old regiments up to strength, states preferred to organize new ones with new opportunities for patronage in the form of officers' commissions and pride in the number of regiments sent by the state. Of 421,000 new three-year volunteers entering the Union army in 1862, only 50,000 joined existing regiments. Professional soldiers criticized this practice as inefficient and wasteful. It kept regiments far below strength and prevented the leavening of raw recruits by seasoned veterans. In 1862 and 1863, many old regiments went into combat with only two or three hundred men while new regiments suffered unnecessary casualties because of inexperience.

Professional soldiers also deplored the practice of electing officers in volunteer regiments. If one assumes that an army is a nonpolitical institution based on rigorous training, discipline, and unquestioning obedience to orders, the election of officers indeed made little sense. In the American tradition, however, citizen soldiers remained citizens even when they became soldiers. They voted for congressmen and governors; why should they not vote for captains and colonels? During the early stages of the do-it-yourself mobilization in 1861, would-be officers assumed that military skills could be quickly learned. Hard experience soon began to erode this notion. Many officers who obtained commissions by political influence proved all too obviously incompetent. A soldier in a Pennsylvania regiment complained in the summer of 1861: "Col. Roberts has showed himself to be ignorant of the most simple company movements. There is a total lack of system about our regiment. . . . Nothing is attended to at the proper time, nobody looks ahead to the morrow. . . . We can only justly be called a mob & one not fit to face the enemy." Officers who panicked at Bull Run and left their men to fend for themselves were blamed for the rout of several Union regiments. "Better offend a thousand ambitious candidates for military rank," commented Harper's Weekly," than have another flight led by colonels, majors, and captains."19

On July 22, the day after the defeat at Bull Run, the Union Congress authorized the creation of military boards to examine officers and remove those found to be unqualified. Over the next few months hundreds of officers were discharged or resigned voluntarily rather than face an examining board. This did not end the practice of electing officers, nor of their appointment by governors for political reasons, but it went part way toward establishing minimum standards of competence for those appointed. As the war lengthened, promotion to officer's rank on the basis of merit became increasingly the rule in veteran regiments. By 1863 the Union army had pretty well ended the practice of electing officers.

This practice persisted longer in the Confederacy. Nor did the South establish examining boards for officers until October 1862. Yet Confederate officers, at least in the Virginia theater, probably did a better job than their Union counterparts during the first year or two of the war. Two factors help to explain this. First, Union General-in-Chief Win-field Scott decided to keep the small regular army together in 1861 rather than to disperse its units among the volunteer army. Hundreds of officers and non-coms in the regular army could have provided drill instructors and tactical leadership to the volunteer regiments. But Scott

19. Wiley, Billy Yank, 26; Harper's Weekly, V (Aug. 10, 1861), 449.

kept them with the regulars, sometimes far away on the frontier, while raw volunteers bled and died under incompetent officers in Virginia. The South, by contrast, had no regular army. The 313 officers who resigned from the U.S. army to join the Confederacy contributed a crucial leaven of initial leadership to the southern armies.

Second, the South's military schools had turned out a large number of graduates who provided the Confederacy with a nucleus of trained officers. In 1860 of the eight military "colleges" in the entire country seven were in the slave states. Virginia Military Institute in Lexington and The Citadel in Charleston were justly proud of the part their alumni played in the war. One-third of the field officers of Virginia regiments in 1861 were V.M.I, alumni. Of the 1,902 men who had ever attended V.M.I., 1,781 fought for the South. When Confederate regiments elected officers, they usually chose men with some military training. Most northern officers from civilian life had to learn their craft by experience, with its cost in defeat and casualties.

Political criteria played a role in the appointment of generals as well as lesser officers. In both North and South the president commissioned generals, subject to Senate confirmation. Lincoln and Davis found it necessary to consider factors of party, faction, and state as carefully in appointing generals as in naming cabinet officers or postmasters. Many politicians coveted a brigadier's star for themselves or their friends. Lincoln was particularly concerned to nurture Democratic support for the war, so he commissioned a large number of prominent Democrats as generals—among them Benjamin F. Butler, Daniel E. Sickles, John A. McClernand, and John A. Logan. To augment the loyalty of the North's large foreign-born population, Lincoln also rewarded ethnic leaders with generalships—Carl Schurz, Franz Sigel, Thomas Meagher, and numerous others. Davis had to satisfy the aspirations for military glory of powerful state politicians; hence he named such men as Robert A. Toombs of Georgia and John B. Floyd and Henry A. Wise of Virginia as generals.

These appointments made political sense but sometimes produced military calamity. "It seems but little better than murder to give important commands to such men as Banks, Butler, McClernand, Sigel, and Lew Wallace," wrote the West Point professional Henry W. Halleck, "yet it seems impossible to prevent it."20 "Political general" became almost a synonym for incompetency, especially in the North. But this

20. O.R., Ser. I, Vol. 34, pt. 3, pp. 332–33.

was often unfair. Some men appointed for political reasons became first-class Union corps commanders—Frank Blair and John Logan, for example. West Pointers Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman received their initial commissions through the political influence of Congressman Elihu Washburne of Illinois and Senator John Sherman (William's brother) of Ohio. And in any case, West Point professionals held most of the top commands in both North and South—and some of them made a worse showing than the political generals. Generals appointed from civilian life sometimes complained bitterly that the "West Point clique" ran the armies as closed corporations, controlling promotions and reserving the best commands for themselves.

The appointment of political generals, like the election of company officers, was an essential part of the process by which a highly politicized society mobilized for war. Democracy often characterized the state of discipline in Civil War armies as well. As late as 1864 the inspector-general of the Army of Northern Virginia complained of "the difficulty of having orders properly and promptly executed. There is not that spirit of respect for and obedience to general orders which should pervade a military organization." Just because their neighbors from down the road back home now wore shoulder straps, Johnny Reb and Billy Yank could see no reason why their orders should be obeyed unless the orders seemed reasonable. "We have tite Rools over us, the order was Red out in dress parade the other day that we all have to pull off our hats when we go to the coin or genrel," wrote a Georgia private. "You know that is one thing I wont do. I would rather see him in hell before I will pull off my hat to any man and tha Jest as well shoot me at the start." About the same time a Massachessetts private wrote that "drill & saluting officers & guard duty is played out."21

Many officers did little to inspire respect. Some had a penchant for drinking and carousing—which of course set a fine example for their men. In the summer of 1861 the 75th New York camped near Baltimore on its way to Washington. "Tonight not 200 men are in camp," wrote a diary-keeping member of the regiment despairingly. "Capt. Catlin, Capt. Hurburt, Lt. Cooper and one or two other officers are under arrest. A hundred men are drunk, a hundred more at houses of ill fame. . . . Col. Alford is very drunk all the time now." In 1862 a North

21. Ibid., Ser. I, Vol. 42, pt. 2, p. 1276; Steven H. Hahn, The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890 (New York, 1983), 118; Wiley, Billy Yank, 220.

Carolina private wrote of his captain: "He put . . . [me] in the gard house one time & he got drunk again from Wilmington to Goldsboro on the train & we put him in the Sh-t House So we are even."22

Such officers were in the minority, however, and over time a number of them were weeded out by resignation or by examining boards. The best officers from civilian life took seriously their new profession. Many of them burned the midnight oil studying manuals on drill and tactics. They avoided giving petty or unreasonable orders and compelled obedience to reasonable ones by dint of personality and intellect rather than by threats. They led by example, not prescript. And in combat they led from the front, not the rear. In both armies the proportion of officers killed in action was about 15 percent higher than the proportion of enlisted men killed. Generals suffered the highest combat casualties; their chances of being killed in battle were 50 percent greater than the privates'.

Civil War regiments learned on the battlefield to fight, not in the training camp. In keeping with the initial lack of professionalism, the training of recruits was superficial. It consisted mainly of the manual of arms (but little target practice), company and regimental drill in basic maneuvers, and sometimes brigade drill and skirmishing tactics. Rarely did soldiers engage in division drill or mock combat. Indeed, brigades were not combined into divisions until July 1861 or later, nor divisions into corps until the spring and summer of 1862.23 Regiments sometimes

22. Bruce Catton, Mr. Lincoln's Army (Garden City, N.Y., 1956), 64–65; Wiley, Johnny Reb, 242.

23. Both the Union and Confederate armies were organized in similar fashion. Four infantry regiments (later in the war sometimes five or six) formed a brigade, commanded by a brigadier general. Three (sometimes four) brigades comprised a division, commanded by a brigadier or major general. Two or more divisions (usually three) constituted an army corps, commanded by a major general in the Union army and by a major or lieutenant general in the Confederacy. A small army might consist of a single corps; the principal armies consisted of two or more. In theory the full strength of an infantry regiment was 1,000 men; of a brigade, 4,000; of a division, 12,000 ; and of a corps, 24,000 or more. In practice the average size of each unit was a third to a half of the above numbers in the Union army. Confederate divisions and corps tended to be larger than their Union counterparts because a southern division often contained four brigades and a corps four divisions. Cavalry regiments often had twelve rather than ten companies (called "troops" in the cavalry). Cavalry regiments, brigades, or divisions were attached to divisions, corps, or armies as the tactical situation required. By 1863 Confederate cavalry divisions sometimes operated as a semi-independent corps, and by 1864 the Union cavalry followed suit, carrying such independent operations to an even higher level of development. Field artillery batteries (a battery consisted of four or six guns) were attached to brigades, divisions, or corps as the situation required. About 80 percent of the fighting men in the Union army were infantry, 14 percent cavalry, and 6 percent artillery. The Confederates had about the same proportion of artillery but a somewhat higher proportion of cavalry (nearly 20 percent).

went into combat only three weeks after they had been organized, with predictable results. General Helmuth von Moltke, chief of the Prussian general staff, denied having said that the American armies of 1861 were nothing but armed mobs chasing each other around the countryside—but whether he said it or not, he and many other European professionals had reason to believe it. By 1862 or 1863, however, the school of experience had made rebel and Yankee veterans into tough, combat-wise soldiers whose powers of endurance and willingness to absorb punishment astonished many Europeans who had considered Americans all bluster and no grit. A British observer who visited the Antietam battlefield ten days after the fighting wrote that "in about seven or eight acres of wood there is not a tree which is not full of bullets and bits of shell. It is impossible to understand how anyone could live in such a fire as there must have been here."24

Amateurism and confusion characterized the development of strategies as well as the mobilization of armies. Most officers had learned little of strategic theory. The curriculum at West Point slighted strategic studies in favor of engineering, mathematics, fortification, army administration, and a smattering of tactics. The assignment of most officers to garrison and Indian-fighting duty on the frontier did little to encourage the study of strategy. Few if any Civil War generals had read Karl von Clausewitz, the foremost nineteenth-century writer on the art of war. A number of officers had read the writings of Antoine Henry Jomini, a Swiss-born member of Napoleon's staff who became the foremost interpreter of the great Corsican's campaigns. All West Point graduates had absorbed Jominian principles from the courses of Dennis Hart Mahan, who taught at the military academy for nearly half a century. Henry W. Halleck's Elements of Military Art and Science (1846), essentially a translation of Jomini, was used as a textbook at West Point. But Jomini's

24. Quoted in Jay Luvaas, The Military Legacy of the Civil War: The European Inheritance (Chicago, 1959), 18–19.

influence on Civil War strategy should not be exaggerated, as some historians have done.25 Many Jominian "principles" were common-sense ideas hardly original with Jomini: concentrate the mass of your own force against fractions of the enemy's; menace the enemy's communications while protecting your own; attack the enemy's weak point with your own strength; and so on. There is little evidence that Jomini's writings influenced Civil War strategy in a direct or tangible way; the most successful strategist of the war, Grant, confessed to having never read Jomini.

The trial and error of experience played a larger role than theory in shaping Civil War strategy. The experience of the Mexican War governed the thinking of most officers in 1861. But that easy victory against a weak foe in an era of smoothbore muskets taught some wrong lessons to Civil War commanders who faced a determined enemy armed (after 1861) largely with rifled muskets. The experience necessary to fight the Civil War had to be gained in the Civil War itself. As generals and civilian leaders learned from their mistakes, as war aims changed from limited to total war, as political demands and civilian morale fluctuated, military strategy evolved and adjusted. The Civil War was pre-eminently a political war, a war of peoples rather than of professional armies. Therefore political leadership and public opinion weighed heavily in the formation of strategy.

In 1861 many Americans had a romantic, glamorous idea of war. "I am absent in a glorious cause," wrote a southern soldier to his homefolk in June 1861, "and glory in being in that cause." Many Confederate recruits echoed the Mississippian who said he had joined up "to fight the Yankies—all fun and frolic." A civilian traveling with the Confederate government from Montgomery to Richmond in May 1861 wrote that the trains "were crowded with troops, and all as jubilant, as if they were going to a frolic, instead of a fight."26 A New York volunteer wrote home soon after enlisting that "I and the rest of the boys are in fine spirits . . . feeling like larks." Regiments departing for the front paraded before cheering, flag-waving crowds, with bands playing martial airs and visions of glory dancing in their heads. "The war is making us all tenderly

25. For a perceptive critique of the "Jominian school," see Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson, Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage (University, Ala., 1982), 146–53.

26. Davis, Battle at Bull Run, 57; Wiley, Johnny Reb, 27; Hudson Strode, Jefferson Davis: Confederate President (New York, 1959), 89.

Stephen A. Douglas

Louis A. Warren Lincoln Library and Museum

William H. Seward

Library of Congress

Free-state men ready to defend Lawrence, Kansas, in 1856

The Kansas State Historical Society

Stockpile of rails in the U.S. Military Rail Roads yards at Alexandria

U.S. Army Military History Institute

U.S. Military Rail Roads locomotive with crew members pointing at holes in the smokestack and tender caused by rebel shells

U.S. Army Military History Institute

B & O trains carrying troops and supplies meeting at Harper's Ferry

U.S. Military Academy Library

Railroad bridge built by Union army construction crew in Tennessee after rebel raiders burned the original bridge

Minnesota Historical Society

Blockade-runner Robert E. Lee, which ran the blockade fourteen times before being captured on the fifteenth attempt

Library of Congress

U.S.S. Minnesota, 47-gun steam frigate, flagship of the Union blockade fleet that captured the Robert E. Lee

Minnesota Historical Society

Above: Abraham Lincoln

Liouis A. Warren Lincoln Library and Museum

Right: George B. McClellan

Louis A. Warren Lincoln Library and Museum

Below: U.S.S. Cairo, one of "Pook's turtles," which fought on the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers until sunk by a Confederate "torpedo" in the Yazoo River near Vicksburg in December 1862

U.S. Army Military History Institute

Jefferson Davis

Library of Congress

Robert E. Lee

Library of Congress

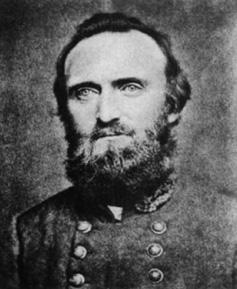

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

Library of Congress

James E. B. "Jeb" Stuart

Library of Congress

Clara Barton

Library of Congress

Mary Anne "Mother" Bickerdyke

U.S. Army Military History Institute

Wounded soldiers and nurse at Union army hospital in Fredericksburg

Library of Congress

"Before" and "after" photographs of a young contraband who became a Union drummer boy

U.S. Army Military History Institute

Black soldiers seated with white officers and freedmen's teachers standing behind them

Library of Congress

sentimental," wrote southern diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut in June 1861. So far it was "all parade, fife, and fine feathers."27

Many people on both sides believed that the war would be short—one or two battles and the cowardly Yankees or slovenly rebels would give up. An Alabama soldier wrote in 1861 that the next year would bring peace "because we are going to kill the last Yankey before that time if there is any fight in them still. I believe that J. D. Walker's Brigade can whip 25,000 Yankees. I think I can whip 25 myself." Northerners were equally confident; as James Russell Lowell's fictional Yankee philosopher Hosea Biglow ruefully recalled:

I hoped, las' Spring, jest arter Sumter's shame

When every flagstaff flapped its tethered flame,

An' all the people, startled from their doubt,

Come musterin' to the flag with sech a shout,—

I hoped to see things settled 'fore this fall,

The Rebbles licked, Jeff Davis hanged, an' all.28

With such confidence in quick success, thoughts of strategy seemed superfluous. Responsible leaders on both sides did not share the popular faith in a short war. Yet even they could not foresee the kind of conflict this war would become—a total war, requiring total mobilization of men and resources, destroying these men and resources on a massive scale, and ending only with unconditional surrender. In the spring of 1861 most northern leaders thought in terms of a limited war. Their purpose was not to conquer the South but to suppress insurrection and win back the latent loyalty of the southern people. The faith in southern unionism lingered long.

A war for limited goals required a strategy of limited means. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott devised such a strategy. As a Virginia unionist, Scott deprecated a war of conquest which even if successful would produce "fifteen devastated provinces! [i.e., the slave states] not to be brought into harmony with their conquerors, but to be held for generations, by heavy garrisons, at an expense quadruple the net duties or taxes which it would be possible to extort from them." Instead of invading the South, Scott proposed to "envelop" it with a blockade by sea and a fleet of gunboats supported by soldiers along the Mississippi. Thus sealed off

27. Wiley, Billy Yank, 27; Woodward, Chesnut's Civil War, 69.

28. Alabamian quoted in McWhiney and Jamieson, Attack and Die, 170; Biglow in Nevins, War, I, 75.

from the world, the rebels would suffocate and the government "could bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan."29

Scott's method would take time—time for the navy to acquire enough ships to make the blockade effective, time to build the gunboats and train the men for the expedition down the Mississippi. Scott recognized the chief drawback of his plan—"the impatience of our patriotic and loyal Union friends. They will urge instant and vigorous action, regardless, I fear, of the consequences."30 Indeed they did. Northern public opinion demanded an invasion to "crush" the rebel army covering Manassas, a rail junction in northern Virginia linking the main lines to the Shenandoah Valley and the deep South. Newspapers scorned Scott's strategy as the "Anaconda Plan." The Confederate government having accepted Virginia's invitation to make Richmond its capital, the southern Congress scheduled its next session to begin there on July 20. Thereupon Horace Greeley's New York Tribune blazoned forth with a standing headline:

FORWARD TO RICHMOND! FORWARD TO RICHMOND!

The Rebel Congress Must Not be

Allowed to Meet There on the

20th of July

BY THAT DATE THE PLACE MUST BE HELD

BY THE NATIONAL ARMY

Other newspapers picked up the cry of On to Richmond. Some hinted that Scott's Anaconda Plan signified a traitorous reluctance to invade his native state. Many northerners could not understand why a general who with fewer than 11,000 men had invaded a country of eight million people, marched 175 miles, defeated larger enemy armies, and captured their capital, would shy away from invading Virginia and fighting the enemy twenty-five miles from the United States capital. The stunning achievements of an offensive strategy in Mexico tended to make both Union and Confederate commanders offensive-minded in the early phases of the Civil War. The success of Lyon in Missouri and of

29. Charles Winslow Elliott, Winfield Scott: The Soldier and the Man (New York, 1937), 698; O.R., Ser. I, Vol. 51, pt. 1, pp. 369–70.

30. O.R., Ser. I, Vol. 51, pt. 1, p. 387.

McClellan in western Virginia seemed to confirm the value of striking first and striking fast.

Scott remained unconvinced. He considered the ninety-day regiments raw and useless; the three-year regiments would need several months' training before they were ready for a campaign. But Scott was out of step with the political imperatives of 1861. Public pressure made it almost impossible for the government to delay military action on the main Virginia front. Scott's recommended blockade of southern seaports had begun, and his proposed move down the Mississippi became part of Union strategy in 1862. But events ultimately demonstrated that the North could win the war only by destroying the South's armies in the field. In that respect the popular clamor for "smashing" the rebels was based on sound if oversanguine instinct. Lincoln thought that an attack on the enemy at Manassas was worth a try. Such an attack came within his conception of limited war aims. If successful it might discredit the secessionists; it might lead to the capture of Richmond; but it would not destroy the social and economic system of the South; it would not scorch southern earth.

By July 1861 about 35,000 Union troops had gathered in the Washington area. Their commander was General Irvin McDowell, a former officer on Scott's staff with no previous experience in field command. A teetotaler who compensated by consuming huge amounts of food, McDowell did not lack intelligence or energy—but he turned out to be a hard-luck general for whom nothing went right. In response to a directive from Lincoln, McDowell drew up a plan for a flank attack on the 20,000 Confederates defending Manassas junction. An essential part of the plan required the 15,000 Federals near Harper's Ferry under the command of Robert Patterson, a sixty-nine-year-old veteran of the War of 1812, to prevent the 11,000 Confederates confronting him from reinforcing Manassas.

McDowell's plan was a good one—for veteran troops with experienced officers. But McDowell lacked both. At a White House strategy conference on June 29, he pleaded for postponement of the offensive until he could train the new three-year men. Scott once again urged his Anaconda Plan. But Quartermaster-General Meigs, when asked for his opinion, said that "I did not think we would ever end the war without beating the rebels. . . . It was better to whip them here than to go far into an unhealthy country to fight them [in Scott's proposed expedition down the Mississippi]. . . . To make the fight in Virginia was cheaper and better as the case now stood."31 Lincoln agreed. As for the rawness of McDowell's troops, Lincoln seemed to have read the mind of a rebel officer in Virginia who reported his men to be so deficient in "discipline and instruction" that it would be "difficult to use them in the field. . . . I would not give one company of regulars for the whole regiment." The president ordered McDowell to begin his offensive. "You are green, it is true," he said, "but they are green, also; you are all green alike."32

The southern commander at Manassas was Pierre G. T. Beauregard, the dapper, voluble hero of Fort Sumter, Napoleonic in manner and aspiration. Heading the rebel forces in the Shenandoah Valley was Joseph E. Johnston, a small, impeccably attired, ambitious but cautious man with a piercing gaze and an outsized sense of dignity. In their contrasting offensive- and defensive-mindedness, Beauregard and Johnston represented the polarities of southern strategic thinking. The basic war aim of the Confederacy, like that of the United States in the Revolution, was to defend a new nation from conquest. Confederates looked for inspiration to the heroes of 1776, who had triumphed over greater odds than southerners faced in 1861. The South could "win" the war by not losing; the North could win only by winning. The large territory of the Confederacy—750,000 square miles, as large as Russia west of Moscow, twice the size of the thirteen original United States—would make Lincoln's task as difficult as Napoleon's in 1812 or George Ill's in 1776. The military analyst of the Times of London offered the following comments early in the war:

It is one thing to drive the rebels from the south bank of the Potomac, or even to occupy Richmond, but another to reduce and hold in permanent subjection a tract of country nearly as large as Russia in Europe. . . . No war of independence ever terminated unsuccessfully except where the disparity of force was far greater than it is in this case. . . . Just as England during the revolution had to give up conquering the colonies so the North will have to give up conquering the South.33

31. Russell F. Weigley, Quartermaster General of the Union Army: A Biography ofM. C. Meigs (New York, 1959), 172.

32. Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command, 3 vols. (New York, 1943–44), I, 13; T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (New York, 1952), 21.

33. London Times, July 18, 1861, Aug. 29, 1862.

Jefferson Davis agreed; early in the war he seems to have envisaged a strategy like that of George Washington in the Revolution. Washington traded space for time; he retreated when necessary in the face of a stronger enemy; he counterattacked against isolated British outposts or detachments when such an attack promised success; above all, he tried to avoid full-scale battles that would have risked annihilation of his army and defeat of his cause. This has been called a strategy of attrition—a strategy of winning by not losing, of wearing out a better equipped foe and compelling him to give up by prolonging the war and making it too costly.34

But two main factors prevented Davis from carrying out such a strategy except in a limited, sporadic fashion. Both factors stemmed from political as well as military realities. The first was a demand by governors, congressmen, and the public for troops to defend every portion of the Confederacy from penetration by "Lincoln's abolition hordes." Thus in 1861, small armies were dispersed around the Confederate perimeter along the Arkansas-Missouri border, at several points on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, along the Tennessee-Kentucky border, and in the Shen-andoah Valley and western Virginia as well as at Manassas. Historians have criticized this "cordon defense" for dispersing manpower so thinly that Union forces were certain to break through somewhere, as they did at several points in 1862.35

The second factor inhibiting a Washingtonian strategy of attrition was the temperament of the southern people. Believing that they could whip any number of Yankees, many southerners scorned the notion of "sitting down and waiting" for the Federals to attack. "The idea of waiting for blows, instead of inflicting them, is altogether unsuited to the genius of our people," declared the Richmond Examiner. "The aggressive policy is the truly defensive one. A column pushed forward into Ohio or Pennsylvania is worth more to us, as a defensive measure, than a whole tier of seacoast batteries from Norfolk to the Rio Grande."36 The southern press clamored for an advance against Washington in the same tone that northern newspapers cried On to Richmond. Beauregard devised

34. See especially Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of UnitedStates Military Strategy and Policy (Bloomington, 1973), 3–17, 96.

35. T. Harry Williams, "The Military Leadership of North and South," and David M. Potter, "Jefferson Davis and the Political Factors in Confederate Defeat," in David Donald, ed., Why the North Won the Civil War (New York, 1960), 45–46, 108–10.

36. Richmond Examiner, Sept. 27, 1861.