17. A Hypothesis for the Twentieth Century?

In this view, we can only understand revolution and nation in their interrelation, a specular recognition that associates the images of their two figures, but also a structural and processual solidarity that connects their effectivity. After 1800, this connection strengthens and becomes tense.

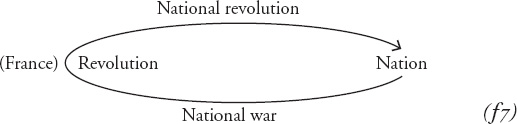

The initial situation thus looks like this:

The revolution is produced as a universalist expansion; it is carried by the expansive movement of the universal. Soon it turns around and comes back to itself as a figure. The point of return is its collision with Germany, where the universal ends up, and a remainder appears: the return is specular, because it is, in the first place, effective, and effectivity speculates. The Revolution then comes back, toward itself, charged with the national idea. It recognizes itself as revolutionary nationalism. It rejoins itself, re-posits itself as the origin, retraverses and doubles itself; and universalism, which is extensive, is recharged with intensiveness. Doubled revolution, revolution of and within the revolution, total revolution. The name of this intensive and totalizing radicalization is socialism.126 Socialism is the appellation of the doubling produced by the turnaround of the revolutionary process, which intensifies and is totalized.

As for the nation, it takes an analogous (effective and specular) turn—but effective because it is specular: speculation works.

The nation exceeds itself, exits from itself to free itself (national war, war of liberation).127 It collides with the (French) Revolution. It turns back to itself, charged with the image of the Revolution and with effective revolutionizing processes. It comes back to itself, as a nation recharged with revolution—national revolution. And it finds itself again, retraverses and reconstitutes itself: revolutionized nation, full and total nation, reconfiguring its movement as fundamentalism [intégrisme], national-revolutionary totalitarianism—as fascism. Fascism is the appellation of the doubling produced at the core of nationalism by its passage across the revolutionary process.

These two—symmetrical—operations shed some light on national characteristics. Socialism, in this schema, is the product of the doubling of the French Revolution, turning around after the failure of its universalist expansion: the doubled Revolution after being reflected in the mirror of the nation. Socialism is therefore a kind of French production. Let us recall that, in the Marxist vulgate, three sources were said to feed the new revolutionary thinking—three national sources:128 political economy (the English theory of capital), (French) socialism, and idealism (philosophical romanticism, which is German). Fascism, on the other hand, is the product of the turnaround of the nation, which retraverses itself after it has been put to the—antagonistic and identity-yielding—test of its conflict with the French Revolution. Fascism did experience its first political victory in Italy and got its name there, but its dominant theoretical apparatus derived from German counterrevolutionary and idealist romanticism.129 Significantly, it first sprang up in countries that were formerly subjected to Napoleonic occupation and rejected it.130

This circulation, both reversible and symmetrical, had not yet produced its last round. With socialism and fascism facing one another in a specular fashion, the perfect setup was in place for the tragedy of the century, which began to coalesce in 1923 and 1924. In 1918, after the Great War ended, it was anticipated that the socialist doubled revolution would resume its universal expansion. Socialist revolution would be worldwide: and European for that matter, at its outset;131 and German at first, for that matter.132 World revolution would start up as a German revolution—and this was what did occur. But in 1923 German revolution drowned in a bloodbath. Socialist revolution then turned around again (the turn of this return can be situated between 1924 and 1929). This can be shown in a figure:

After the German failure of the European revolution, socialism withdrew to become socialism in a single country. It rejoined itself and doubled up, as if re-traversed by the national—a socialism overintensified and oversocialized by the national appropriation: one may point to this with the empirical designation of Stalinism. Like Salazarism or Gaullism, “Stalinism” delimits a fact, which calls for a concept: nationalized socialism.133

As for fascism, it spreads out in the space left open by the withdrawal of the revolution: a European counterrevolution, in accordance with the project formed and formulated by Hitler as early as 1924, but that, significantly, does not unfold until 1932, when Stalin’s power grab stabilizes. Lenin dies in 1924, but the movement solidifies during ferocious battles between 1928 and 1932.134 The year 1932 settles Stalin’s victory. In the following year, Hitler is brought to power. The plans of German fascism, developing since 1920–24, are implemented against the European counterrevolution, seeking to crush European Bolshevism in hand-to-hand combat so as to retrieve from this struggle its own identification as socialism: a counterrevolutionary nationalism turning back on itself, tested by this conflict, as a socialist and complete ultrarevolution; a total, social nationalism, revolutionizing society as a whole; a social nationalism—national socialism. It is shown in the next figure:

The tragedy of the century: national socialism and socialism (which is national) face off and go to war, claiming to leave in the world no other space than the one devastated by their battlefields.

It is worth noting three things about these schemas.

(1) It may be in this relationship of structural solidarity and reversed identification that one should seek an explanation for the frequently noted phenomenon converting one commitment into another: Benito Mussolini, Jacques Doriot, and Marcel Déat cross over from socialism to fascism. It is a widespread phenomenon, which has lately had some new and striking illustrations. It is worth noting that this exchange is only weakly reversible: few avowed fascists have become communists or revolutionary socialists. This dissymmetry has remained unexamined; one might suggest, however, that just as nationalism is an answer, or a figural re-turn of the revolution, fascism is a doubling of figurality facing socialist figurality, something like a return to the return—so that, despite the connection between the two branches of the process, there is no equivalence whatsoever between them, in particular as far as the psychic models required for a commitment are concerned: crossing over to fascism was a passage to more figurality and identification, whereas the passage to communism, in spite of everything, retained a dis-identifying, transporting, and metaphorizing element from its provenance. And the times tended more toward figures than transport.

(2) One can only comprehend Nazism and Stalinism in their mutual relation, one before the other and even, in a certain way, one within the other (each rolled up within the other as in its fold). No equivalence here either: Stalinism was the offspring of the failed world revolution, whereas Nazism was its sworn enemy. The first preceded the second: the one more forward going, the other more entwined in returns. Nonetheless, at that stage of their history (when nationalism had vampirized the revolution, transforming it into this restless corpse, this living dead socialism in a single country), they were welded to one another by the identity-seeking inveiglement that constituted them together and made them devour each other in the embrace of their monstrous coupling. For nationalism, this vampirization was the natural order of things, since the nation had to do with identity in its very principle. For the revolutionaries, who wanted to launch other ventures and believed in this—provisionally to put it this way—it was a real shame.

(3) In any case, this interpretation gives rise to a hypothesis that helps us understand what was such an enigma for so many among them—for so many among us. Why was revolutionary thought so helpless when it came to thinking about the nature of “Stalinism”? The reason is (almost) plain: one would have needed to understand the fundamental dependence of this historic formation upon Nazism, and therefore understand that the whole edifice of the revolution (the edifice of the state, the political and intellectual edifice) rested on this internal and architectonic coupling between the two regimes. This was not about two variants of the common species “totalitarianism,” however. Their link had to do with a processual and structural solidarity, being twins; a link of essence and birth that did not let one regime exist without its struggle to the death against the other—a battle for identity, but to death; thus a battle against oneself, made of suicides and scant respite; alliances of tyrannies to give themselves some time to survive and delay the start of their common disaster. Understanding “Stalinism” would have meant understanding how it was essentially joined to Nazism, which meant that Stalinian “transgrowth” of the revolution could only be read as the transformation of the revolutionary process under the effect of its struggle against fascism, as a certain of in-corporation of fascism into the revolution. And so, revolutionary thinking could not really analyze Nazism either; this would have required that the revolution understand itself and its own national transformation as an incorporation of fascism, and the transgrowth of fascism into Nazism as a reappropriation of identity in a stopped revolution. To be fair, one should mention that certain intuitions of the extreme Left, or of a certain Freudo-Marxism, were not far removed from perceiving this. They paid a price for this—a high price. The secret wasn’t worth it.135