29.

What about Europe? Lately it seems to have been forgotten in these pages. To be sure, the erasure of its name and theme has been intentional—even if all that we have been dealing with in this last part can rightfully be qualified as European: world globalization, world-image, capitalism and its imperialism, communism, revolution, historicity. All that seems to have come out of Europe. Let us come back to this for a moment.

Our initial hypothesis was as follows:

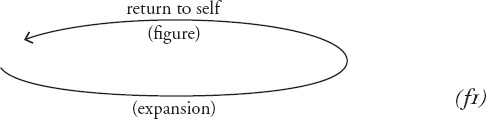

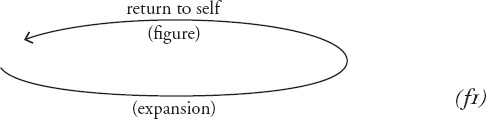

“Europe” is one of the names of the return to self of the universal, which is to say, of the universal as a figure. (h1)

This means to say that Europe counts as one of the places that produced the universal and elaborated the idea of universality. But of this work it has not accomplished anything as a return (in its returning phase), nor as a figure, then—nor then ultimately as “Europe.” In other words, even if it is supposedly “European,” this elaboration of the idea of the universal was not the product of a meditation about Europe but about universality. The work, implementation, and operation of Plato, Newton, and Freud (to pick some arbitrary examples) were not carried out as elaborations of the theme, or the schema, of Europe. The question of Europe as such has come to light by way of a return toward its operations and possibly (though rarely) a turnaround of these operations. Let us recall the structuring schema:

The expansion supports the return, which carries it forward, in a certain fashion, and has the same nature. But the return reverses the expansion and sends it back to its supposed starting point. The expansion did turn around at one point, as if hitting a stumbling block, or something exhausting it. And so, insofar as it turns itself (its image, name, and figure) around, Europe is the product of the reversal of the movement of the universal, that is, the product of its stopping and fatigue. While Europe has thus counted as one of the—eminent and singular—places of the production of the universal, it is not as “Europe” that it has worked it out, while thinking of and regarding itself as Europe, and so naming itself. Europe named itself Europe precisely when this work was stopping, entering a phase of exhaustion and reversal. And thus—to make my intentions completely clear—I have ceased to speak about Europe so as to take up again in my own way the gesture of European productivity.

This may be exactly what the myth tells us, or rather the legendary, literary, and very late variant of it that has reached us. It is not as if the myth had foreseen or announced a historical development (the formation of Europe), which came about much later. But the structure of the myth simply made it available to symbolize or allegorize the European feature that is our topic—and this explains, among other things, that Europe rather than another figure was chosen to designate this development. Indeed, being torn from her native land is what happens to Princess Europē and what the myth recounts. This abduction happens to an Asian woman; Europe is torn away from Asia. The abduction suits her desire—her nocturnal, secret, and amorous hopes. When it is announced, it makes Europe concerned and quivering with excitement. This Asian daughter wants to be abducted: Asia has also begotten this desire for abduction, this hope to leave and be carried away from her native place. Among young women, Europe is the one who has the vision for this project: we know that she can see far and wide.120 But the land to which her abduction transports her—the land she sees, and foresees in her dream—is the nameless land on the other side. And Europe does want this very thing: to be torn from her soil, her birthplace, toward an unknown and unnamed place in the west. In this way the matter that is more European than any other is the matter of the production of America. America is the exhibited becoming of Europe as Europe: the far-off vision of an unknown land in the west, where one wishes to be carried away. Europe is entirely this desire of westernness, this westward run, always westbound, no doubt behind the sun, which it wants to follow or join, and make it impossible for the sun to drop in the sky or set—like Joshua wanting to halt the sun and the moon [Josh. 10:12–13], or Leon Trotsky death as much as the sun. Europe does not want to stop the sun but rather to follow its ride indefinitely and prevent the venture from coming to an end, banish falls and declines, settle indefinitely in the journey itself, take its place in the chariot, sail to the west, endlessly, from one unknown to the next. In this surge—continually relaunched—Europe has produced the world as world. That is why worldhood is European in essence: worldhood is the appellation of the very project of Europe, as self-discovery, discovery of this being-Europe, the new and unknown land that one pursues after being carried off across the sea.121

But here it is: the journey turns itself around, through its completion; it finds and joins its point of departure again; and the production of the world is achieved as globalism. It is in this return to itself and this turnaround that Europe recognizes itself as Europe: otherwise it was simply the universe—the world of the empire, the Catholicity of the church, the oikoumenē of any inhabited or traveled land. And then, as universality, it is superseded by this new empire that it has brought forth: by capitalism and its world; by the worldwide character, becoming-world, and world-image of capital. What is most European, then, is the world as world, that is, the cessation of Europe. The universalist project deports itself from Europe as such, and Europeans, putting this into words, will henceforth rely on the idea-of-world, planetarism or cosmopolitics, world citizenship or world revolution, world-city or city-world, the great universal city of men called to appear before itself in complete transcontinentality. In this phase, Europe is no longer necessary for the universal. If it reconfigures itself, as Europe, it is necessarily out of fear and by retreating in front of this worldhood that dissolves it within itself, henceforeward out of patriotism, continental nationalism, protectionism of the soil, denying all that it has done and constituted: this worldhood itself, which is nothing but its child—additionally, the name of its operation, in tearing itself away from its birthplace, its nationality always dismissed. Two Europes confront each other, then, and they are doubly impossible: one Europe that is nothing but world globalization itself and only wants Europe as its own abolition; and one Europe that turns around toward itself as a continentality of identities and nationalisms, and for that matter has to deny all that Europe has done, thought, and produced since its inaugural abduction. At this point, there is not much one can do with Europe: if one chooses its universal vocation, it is the world that is involved. As for a national reappropriation, Europe is hardly suitable.

But here it is. Let us imagine that what this book has said is ever so slightly relevant. What it brings out is that the world, too, is now exhausted; that it is not the world that is needed; that what has to be done is to exit the world—because the world is the name of the domain subjected to imperial domination—nowadays to capital—and the world henceforth and irreversibly is the world of commodities, world-commodity, and that one has to come out of this, traverse it, set oneself free from this, leave it alone, change histories. But without turning back, without returning to the supposed point of departure: instead, coming out ahead, onward, where our steps lead and where we are looking. An exodic program, as it were: to exit the world of servitude, to come out of servitude-as-the-world, to travel across the desert, to pass across to the other side. What offers itself in this crossing—according to Spinoza—is law, its common constitution, the form and possibility of commonality.122 It is about exiting the world-of-domination to cross over to being-in-common—about letting go of being-in-the world (being-there) so as to be-in-common, one might almost say provocatively. And there is no way of knowing yet whether this program can be thought as “being,” or whether letting go of being is involved—a curious forgetting of being—for the experience, sharing, and practice of the common. This is something Althusser would call a “change of terrain,” for thinking as well as praxis, from thinking to the thinking of praxis—a new experience and practice of thinking.

Supposing it is like this—that it is now the time of untaking, un-grasping, and dispossession of the world, disbeing in the world—we may have something to do with Europe, anew. For if Europe was one of the places where the universal was elaborated, the program may now be to follow up on this elaboration in one of its (new) phases: the elaboration of a universal set free from the world of servitude, from the commodity; not as a program to disenslave or decommodify the world, but as a disenslaving, decommodification, and thus deworldization of common-being. A universal after the world: this is the work one may now undertake, in Europe and elsewhere. But while Europe may count as a place where this program is elaborated, it could not be so as Europe—so much is clear. It can be, no doubt, thanks to the pursuit and more thorough inquiry into everything, about the universal, elaborated here—as well as elsewhere, but perhaps more so and more irreversibly so. But in no way can it be through the retreat or turnaround toward its own gesture as a European one, in the quest for the contents, the figure, and the identity covered by this name. Moreover, Europe is quite clumsy at this. It can only be in the broadening of its views, opening wide its large eyes—and not in scrutinizing its mirror. Perhaps Europe can help to liberate us from the world (but this “us” is “everyone in the world”). Looking far and wide. For, to be sure, beyond the horizon of the world, we see nothing now—letting oneself be carried away by desire, removed from one’s native land, to transport oneself toward a beyond-the-horizon so remote that one can neither name it nor see it yet, nor even confirm its existence.

This is what a certain powerlessness on the part of Europe (henceforth) conveys—powerless to be excited by what it contains and by its own essence, powerless in nationalism, powerless to love its own figure. And in this it expresses the best thing it has: its native extraversion, its unnamed, intemperate universion. This is the good fortune we can foretell for Europe: the emptiness of its figure is its positive future.