Once you’ve experienced the beauty and usefulness of a flower garden all summer, you’ll mourn the coming of autumn. But if you’ve been looking ahead to the drab days of winter, you can preserve your garden’s bounty for dried-flower bouquets, arrangements, wreaths, and other crafts. A dried-flower garden can be the same garden you’ve used all summer for fresh flowers, or you can specialize in flowers for preserving.

For the commercial grower, “drieds” can bring a welcome influx of cash at the end of the season. Many flowers that you’ve been harvesting all summer will be invigorated by the cooler weather of September. When the frost date gets closer, you can start harvesting those abundant flowers for drying, so that nothing goes to waste. A few baskets of drieds keep your market stand looking colorful and attractive well into fall. And many growers find that the diminishing amount of farm work in fall gives them time to add value to their dried flowers by crafting with them. The dried-flower business is not as strong as it was when I wrote the first edition of this book in the 1990s. In part that’s because of the vast improvement that has occurred in artificial flowers, now known as “silk botanicals.” High-quality silk flowers are so realistic that I sometimes have to touch them to know whether they are real or not. But flower trends come and go, and it’s possible that the dried look will return in a big way one of these days. Until then, there is still a steady, although not booming, market for dried flowers.

Virtually any flower can be preserved by one method or another. The easiest way is to air-dry them, but this is effective only with certain species. Flowers also can be preserved with glycerin, which is taken up through the flower’s stems, replacing water and leaving the blossom soft and lifelike. Small, thin-petaled flowers (such as pansies and violets) are best preserved by burying them in silica, which looks like sand and absorbs the water from the flowers. Finally, there’s freeze drying, which can preserve nearly anything, no matter how fleshy or moist, but which is available only from businesses that own the necessary but very expensive freeze-drying machines.

The only equipment you need for air-drying flowers is a warm, dark place with good air circulation. If your drying room is too bright, the flowers’ colors will fade. Likewise, if the flowers aren’t dried quickly, they will fade or turn brown. For most flowers, you can use any room that has low humidity. (Running a dehumidifier or small heater helps if your climate is humid.) A barn with a hayloft is an excellent place to dry flowers; a garage or garden shed works well, too, if you can open windows or run a fan to keep the air moving. Cellars are usually too damp for drying flowers, but they may be suitable in dry climates or during a dry summer. In many cases, small farmers use their greenhouses, provided that no plants are growing there in the summer, and cover the entire structure with either black plastic or black landscape fabric. Alternatively, they build a tent of black plastic inside the greenhouse. Larger commercial growers construct special buildings where they can apply heat to kiln-dry the flowers quickly.

Flowers should be picked at the peak of perfection if you intend them to be everlasting. (Why preserve a sad-looking flower? It will only get sadder.) The optimum time for picking a flower to dry is generally the same as the best time to pick it for fresh use. In the list of recommended cut flowers in appendix 1, you’ll find guidance on the best harvest time for each recommended species.

To maximize hanging space, tie three 12-inch lengths of string to wire or plastic clothes hangers. Bunch harvested flowers with rubber bands. Slip one bunch over each string and pull the string tight.You can also hang bunches from individual nails in rafters by their rubber bands. Or hang numerous bunches on a piece of lath, then suspend the lath between the rafters.

Pick your flowers in the late morning, after the dew has dried but before they are subjected to the heat of the day. Make sure they are free of moisture, because mold will quickly cover wet plants hanging in a dark place. Gather the flowers into small bunches fastened with rubber bands. Then hang the bunches upside down in your drying area.

Check the bunches every few days to see if they are dry. You’ll be able to feel when the flowers are dry, but to be sure the entire bunch is ready to be taken down, try bending one of the stems near the bottom, where it was covered by the rubber band. If the stem snaps, the flowers are ready. If it’s still flexible, hang up the bunch again to dry some more. This is very important. There’s nothing more disappointing than putting away bunches of flowers you thought had dried only to find a few months later that a bit of remaining moisture has turned the whole boxful moldy and musty.

Once the flowers have dried, wrap them in tissue paper or newspaper, and put them in boxes that can be sealed from the light. They should be stored in a dry, warm place until you’re ready to use them.

Drying Upright

Some flowers keep their shape best if they are dried standing up rather than hanging upside down. To get them started, stand the flowers in an inch or two of water in a container that you have placed in a dry, dark place. The flowers will look like fresh-cut flowers for a few days but will gradually dry after the water has been taken up from the vase. The list of recommended cut flowers in appendix 1 mentions those that are best preserved in this way.

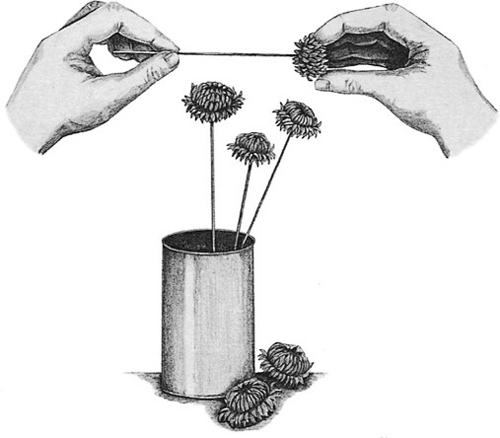

Some blossoms that are great for drying have stems that won’t stay rigid no matter what you do. Strawflower is the prime example. If you want to use strawflowers for wreaths or in other projects where you will just glue on the blossoms, you can simply pinch the flowers off the plant before they are fully open and dry them in a shallow box or basket in your drying area. If, however, you want to use the blossoms in arrangements, you should insert a florist wire in place of each stem soon after you have cut the flowers. After you’ve pushed the wires into the bottom of the flowers, stand them upright in a can in your drying place. As the flower dries, it will shrink and tighten its grip on the wire.

Helichrysum stems are too weak to hold up the flower heads when dry, so it is best to insert a florist wire into the base of the blossom as soon as it has been cut. As the flower dries, it will tighten onto the wire.

Flowers that get too brittle when air-dried often can be preserved with glycerin, a colorless and odorless syrupy liquid that is used in hand lotions and other cosmetics. The glycerin is taken up by the stem like water, and it replaces the natural moisture in the flower. Flowers treated with glycerin retain a soft feel and won’t shatter when handled. Statice (Limonium sinuatum) is one flower that can be easily air-dried but is commonly preserved with glycerin for the floral industry because it retains a much more lifelike feel. Glycerin is also the only way to preserve most leaves, and foliage can add a new dimension to your floral designs.

Most preservers also combine floral dye with glycerin, for two reasons. First, watching the dye move up the stem lets you know when the process is complete. Second, dye gives the flower or stem a more vibrant color to match its soft feel. Many popular dried plants, such as baby’s breath (Gypsophila paniculata) and bunny-tail grass (Lagurus ovatus), are often dyed in designer colors when they’re glycerinized. Statice is commonly dyed green to make the stems look fresh. (Except for occasional bleeding into white statice flowers, the dye won’t show up in the blossoms.)

If you’re using glycerin, pick flowers when they are fully mature, because immature or aging blooms will not take up the solution readily. Mix one part glycerin with two parts warm water. Use only an inch or so in the bucket, because you will have to replace the solution for each new batch. Stand the flowers in the bucket, in a dark place, and leave them in the solution for a week or so, until the top blossoms have a silky feel. When the glycerin has been absorbed throughout the flowers, take them out of the solution and hang them upside down in a warm, dry place to finish drying.

You also can preserve leaves by immersing them in glycerin solution; this process usually takes about the same amount of time as glycerinizing through the stem.

Some flowers that are too fragile to air-dry or glycerinize can be preserved in silica gel crystals, a desiccant. Silica crystals made for the purpose of flower drying have color indicators that turn pink as they absorb moisture. When the silica gets damp, it can be dried in a low oven (250°F, or 120°C) for two to three hours, until the color indicator becomes blue again. With this technique, the crystals can be reused almost indefinitely. You can buy them at a wholesale florist supply outlet or at a craft shop.

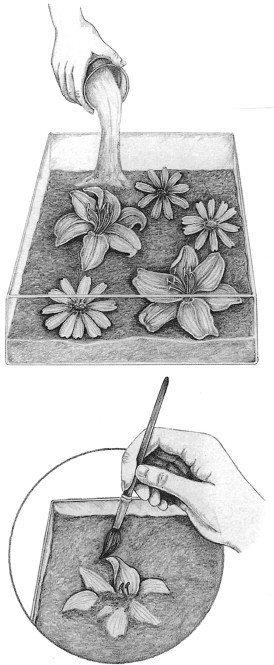

To dry flowers using this method, put a couple of inches of silica gel crystals in an airtight plastic storage container. Lay the blossoms faceup, with stems removed, on top of the crystals. Make sure that the flowers aren’t wet and aren’t touching one another. Gently pour the silica crystals on top of the blossoms, burying them completely at least a half inch deep. Close the container tightly and put it in a dark place. Check the flowers after two days to see if they have dried. Uncover them gently, using a paintbrush or cotton swab, as they will be fragile.

The trick to drying flowers in silica is in the timing. If you leave them in too long, they become brittle and may fall apart when you try to use them. If you don’t leave them in long enough, they will quickly rehydrate and go limp when exposed to humid air. So check your containers every day after the first twenty-four hours and remove any blossoms that have dried. Most flowers will be sufficiently dry within two to four days.

Many crafters spray their silica-dried flowers with a type of polyurethane coating specially made for floral use. It’s not what I would call an organic substance, though, so be careful to use it sparingly and in a well-ventilated place. If you live in a humid climate, it may become obvious to you that dried flowers need a protective coating in order to last, but in drier climes you can probably forgo this step. Store uncoated silica-dried flowers in another airtight container that has just a trace of crystals spread across the bottom to prevent reabsorption of water. Keep the container in the dark until you’re ready to use the flowers, in order to prevent colors from fading.

Place flowers blossom-up in a container and pour silica crystals over them. After a day or two, unearth them with a paintbrush.

Silica-dried flowers can be used flat, hot-glued to wreaths and swags. If you want to use these flowers in arrangements, you can glue them to a stiff wire that you then wrap with green floral tape to look like a stem.

Silica drying may seem like a lot of trouble, and it is. However, this method does produce beautiful results from flowers that otherwise would not dry well. I have used silica to dry lilies, fully opened roses, and pansies—none of which could be air-dried. A handful of these delicate, colorful blossoms can go a long way in crafting, and they will add a distinctive look to your creations. Even commercial growers who sell wreaths and other value-added products will find it advantageous to accent their crafts by preparing small runs of silica-dried flowers.

Freeze drying is a method of preserving flowers that leaves them looking nearly lifelike. As with any preservation method, freeze drying removes water from flowers, but it does so by taking the water from a liquid to a solid state, and then to a vapor. When done properly, there is little tissue damage, so freeze drying produces truer color and flower shape than other preservation methods.

For a short time in the 1980s there was a boom in the freeze-drying industry, as many small-scale crafters, growers, and florists purchased freeze-drying machines with hopes of making a fortune. Prices for freeze-dried floral material were sky-high, and so was demand. Entrepreneurs penciled out the money they could make, and it looked like a great business opportunity.

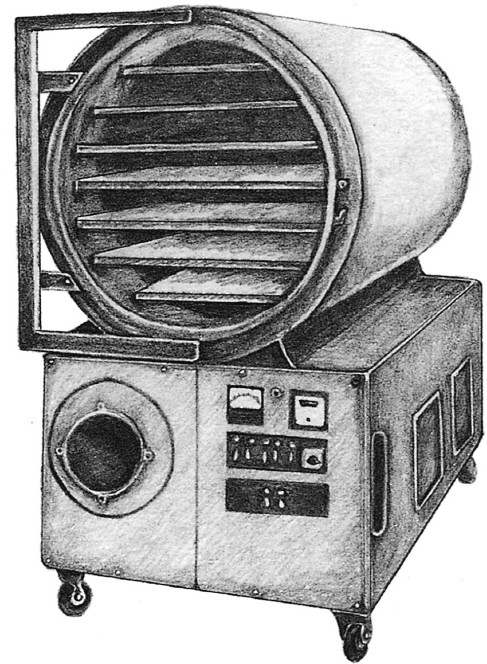

A commercial freeze-drying machine for flowers

Unfortunately, the freeze-drying business turned out to be a financial catastrophe for many small enterprises. Running a freeze-drying machine was more time-consuming and labor-intensive than expected; lack of service and frequent breakdowns put machines out of commission for long stretches of time. Moreover, some machines took much longer to complete a drying cycle than the owners had been led to believe. The result was that production—and revenue—often fell far below the levels predicted in the business plan. Some owners simply couldn’t pay back the loan they had taken out on the $40,000-plus freeze-drying machine.

Still, many freeze-drying businesses are humming along profitably. Freeze-dried flowers and vegetables can command up to $5 apiece retail, and they also can be sold wholesale, direct to florists locally, and by mail-order. Preserving wedding bouquets and other keepsakes has become a big business for some freeze-drying companies.

If you would like to purchase freeze-dried material for your own use, contact the International Freeze-Dry Floral Association, listed in appendix 2. This group can give you a list of members in your area who sell to the public. And if you’re interested in pursuing freeze drying as a business opportunity, join the association and attend a conference before you invest your life savings. Members will give you the true scoop on the business.

Controlling Dried-Flower Pests

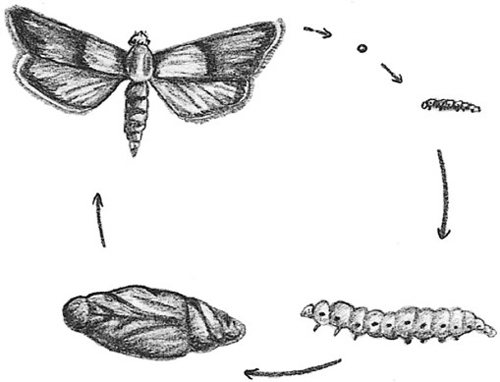

Indian meal moths, the same kind that get into flour and other grains, often infest dried flowers, both in storage and when they’re made up into an arrangement. Some growers put pheromone traps into boxes of stored flowers. The traps will attract only the males, however, and a few males will still find their way to females and mate. Consequently, pheromone traps are probably better used to monitor your flowers for the presence of the moths. In many commercial dried-flower operations, cardboard strips impregnated with insecticides are added to the stored flowers. (That’s another good reason to grow your own!) Here are several organic control methodss for meal moths; some are more appropriate to home gardeners, and others are best used by commercial growers:

The life cycle of the Indian meal moth

Grains and grasses are popular among dried-flower growers, but cutting the thin stems is a time-consuming task. Many growers in recent years have purchased a piece of Japanese rice-harvesting equipment called a crop binder to help with the job.

The crop binder is built like a walk-behind tiller, with a motor and transmission that propel it. As you walk down the crop row behind the machine, sickle bars on the front cut the crop at ground level; tines then lift the crop and move it into the machine, where a packer similar to a hay baler bundles it. When the bundle reaches a prescribed weight, a door is activated and the bundle is tied up and ejected from the machine.

“They will go through a field as fast as you can walk,” says Max Webster, whose company, Willamette Exporting, imports the machines from Japan. “They can eject fifteen to thirty bunches a minute.”

Although these machines work best with grains and grasses, they also can be used with certain flowers such as gomphrena and larkspur, where the entire plant is harvested. At a cost of $7,000 to $10,000, they are designed only for commercial operations.

For more information, contact Willamette Exporting, 7330 S.W. 86th Avenue, Portland, OR 97223; 503-246-2671; www.europa.com/~wex/.

• Put the flowers in the freezer for four to seven days. The larvae will be destroyed and your problem will be resolved. If you see meal moths flitting around your house in winter, you should suspect that there has been a hatch in your dried-flower arrangements. If it’s well below freezing outside, move the arrangement to an unheated garage, porch, or shed for a few days to kill any remaining larvae. Swat the slow little moths inside your house so they can’t reinfest the flowers when you bring them back inside.

• Shortly before harvest, spray the flowers with Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a type of bacteria that kills only certain species of caterpillars, including the larvae of the meal moth.

• Use heat to dry out the moths and their larvae. Temperatures of just 105 to 110°F (40 to 43°C), sustained for twenty-four hours, will kill all stages of the meal moth. Higher temperatures work faster; only twenty minutes is required at 150°F (66°C).

• Apply sorbic acid, a common food additive, which has been found to kill insects in stored products. It can be sprinkled in boxes or around buildings.

If you’re drying grains as well as flowers, be aware that mice will view your drying shed as an all-day buffet. The first year I grew wheat for drying, I hung it in bundles from nails on the barn wall and was amazed to find that mice had figured out a way to walk up the walls to feast on the wheat. Afterward, I always hung my grains from wires suspended across the room. I half expected some tightrope artist to make its way across the wire to the wheat, but that hasn’t happened yet.

Karen Pendleton hangs statice and sunflowers in the grain bin that she uses as a drying shed on her Kansas farm.

Commercial Dried-Flower Production

Dried flowers, which seemed like a fad a decade ago, have settled into their status as a staple of the floral industry. Peak demand is seasonal, beginning in the fall and running through spring, but it’s reliable. Marketing opportunities abound for dried flowers.

• Most market gardeners will find that drieds, particularly in mixed bouquets, sell well at farmers’ markets during the summer and can help extend the retail season well into the fall. Dried flowers can provide the critical mass that a grower needs to attract customers to the stand for other autumn crops, such as pumpkins and winter squash.

• Many larger farmers—particularly in prairie regions—have converted part of their acreage to dried flowers and do a good business selling them wholesale. With a few dried products such as wheat, grasses, and some direct-seeded flowers, production isn’t much different from regular row-crop farming. Harvest, post-harvest, and marketing are entirely new, however, so the farmer who wants to get into the dried-flower business can expect to increase his or her workload considerably.

• On-farm markets can increase sales with value-added dried products, including mixed bouquets, wreaths, and other crafts. Craft classes are potentially a good way to generate revenue on farms that can offer some kind of indoor workspace, such as a bright and clean barn.

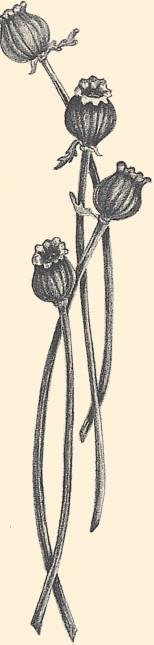

Poppies have become a mainstay in the dried-flower business because of their interesting pods. The most popular cultivar for dried use is ‘Hens and Chicks’, which has a large central pod surrounded by dozens of tiny pods. It is one of several beautiful and useful varieties in the species Papaver somniferum, or opium poppy.

Unfortunately, growing and/or possessing P. somniferum is illegal in the United States because opium, an illegal drug, can be made from the sap of the plant. It’s also illegal to possess “poppy straw,” which includes any part of the plant other than the seeds.

For many years, the law against growing P. somniferum went unnoticed by flower growers and dried-flower wholesalers, who were doing a booming business in poppies. But in the 1990s, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States Department of Justice began taking action against poppy growers. Many farmers and wholesalers received warnings, and seed companies were asked to stop selling the seeds. In 2004, the DEA raided a flower farm in California and destroyed nineteen thousand poppy plants. The owner was not charged, the DEA said, because it was pretty clear that he was growing them for the flowers, not the opium, and was unaware of the illegal status of the plants.

Rather than run the risk of having DEA agents stomping through your fields, you might want to grow a poppy other than P. somniferum. Dried-flower growers say the next-best poppy to grow for dried pods is the perennial Oriental poppy (Papaver orientale), which has fairly large pods, though not as large as those of the opium poppy. Several other poppies have interesting pods, but they are small.

• Some growers switch from farming to crafting in late summer and make the rounds of autumn and Christmas craft fairs. Dried-flower crafts can prove quite profitable for growers who can convert a few dollars’ worth of their own product into $60 wreaths. Labor is the one pitfall, however. Crafters who come up with designs that can be produced quickly will come out ahead. By contrast, elaborate, time-consuming crafts are likely to be money-losers once your own labor is taken into account.

Even simple bunches of dried flowers become value-added products when you wrap them in a square of florist paper and tie them with a piece of raffia or ribbon. A basket of dried-flower bouquets, attractively wrapped, will bring customers to your farmers’ market stand and spur many impulse purchases. Remember to keep your drieds out of the sun to prevent them from fading, so that you can sell any leftovers the following week.

For direct sales, price your dried flowers higher than your fresh ones. If you make prices the same for fresh and dried flowers that are equally beautiful, you will cut into your fresh-flower sales. And try to sell most of your drieds direct to the final consumer: The markup on dried flowers at a florist or gift shop is substantial, which means that you can make a good profit by pricing yours competitively when selling to the consumer.

VALENCIA CREEK FARM

Aptos, California

When Chris Banthien built her flower farm on a steep hillside near Monterey Bay in Aptos, California, she knew she would have to specialize in flowers that could withstand hot sun, ocean fogs, and sandy soil. She chose Mediterranean herbs as her main crop, and the choice proved an ideal match for her climate. On the terraced hillside below her house, Chris grows about 5 acres of lavenders and ornamental oreganos, which she sells to wholesalers and at farmers’ markets. She has six hundred hydrangea plants around a pond on the ranch. And she dries her flowers and crafts them into wreaths and other designs.

But Valencia Creek Farms has diversified in several directions in the twenty-plus years Chris has been in business. She has planted two thousand olive trees imported from Italy, from which she produces her own award-winning brand of olive oil, Olio delle Colline di Santa Cruz. The herb and olive businesses overlap in several other fragrant products: olive-oil-based soaps scented with lavender, citrus, basil, and lemon verbena, and lavender-infused chocolate truffles that use olive oil rather than cream.

Chris grows half a dozen varieties of lavender that are strikingly different from one another. The flowers of ‘Provence’, for example, are much lighter than the dark purple flowers of ‘Hidcote’, but the foliage is grayer than that of ‘Grosso’. Fragrances vary, too, and Chris can tell in a breath which lavender she is handling. She grows as many kinds of oregano, too, which comes as a surprise to people who think of it only as a culinary herb. In fact, the genus Origanum is large, and sorting out the names of its many species causes confusion. They range from short, shrubby plants with tiny pink flowers to tall, rangy plants with big, round bracts like hops. While only a few of the oreganos are used in cooking, nearly all of them are lovely fresh or dried. Chris grows about a dozen varieties and finds that they cross-pollinate freely, resulting in hybrids that may be unique to her farm. Some of her favorites include:

• O. laevigatum ‘Hopley’s Purple’, which has tall purple stems and purple flowers.

• O. dictamnus ‘Dittany of Crete’, which produces small, hoplike bracts that are green when mature.

• O. rotundifolium, which has green, hoplike bracts up to an inch in diameter. The bracts are light green when dried.

• O. rotundifolium ‘Kent Beauty’, which looks like the preceding variety, but the bracts have a rose tint.

If you hope to sell to craft stores, florists, and gift shops, be prepared to accept low prices. These shop owners can purchase high-quality dried bouquets and arrangements at unbelievably low prices from wholesalers. You can find out prices easily on the Internet. Search for “dried flowers” and visit the Web sites to see if prices are listed; many are. Floral wholesalers (the place where you buy supplies) often sell dried flowers, too. Studying their offerings will give you ideas for what to grow, as well as an understanding of the quality that florists expect. In general, your flowers are going to look a lot better than a wholesaler’s; once you realize this, you can use it as a selling point.

Even the common culinary oregano provides good flowers for drying. O. vulgare, subspecies vulgare, has pink flowers enclosed in purple bracts.

When Chris started her business in 1989, she primarily sold dried herbs at farmers’ markets. But then a few floral wholesalers found out about her unusual herbs, and by 1996, more than half of her revenue was coming from wholesale sales of fresh-cut herbs. Although much of her production is now sold as fresh flowers, Chris still makes use of the spacious hilltop barn she built. She has devised a system to hang herb bunches quickly and with plenty of air circulation. A wooden frame with wires stretched across it creates the framework. Plastic clothes-hangers are always standing ready, with a piece of string attached to the bottom bar of the hanger. As the bunches come in from the field, bound with rubber bands, the string is slipped up through the middle of the bunch, where the rubber band holds it in place.

Chris grows other herbs and flowers, most of them quite unusual for northern California. She raises several varieties of ornamental wheat and triticale, a wheat-rye cross, for drying. She also grows Helichrysum petiolatum (curry plant). In her climate, this fuzzy-leaved plant, which is grown in window boxes elsewhere in the country, grows to 7 feet tall and as big around. Monarda citriodora (lemon mint), with its whorls of purple flower bracts, and Craspedia globosa (golden drumsticks) are also popular for her.

Valencia Creek Farms was solely a flower business until one day in 1997, when Bruce Golino showed up at her farm and suggested she plant olive trees in a decrepit apple orchard on her property. Bruce is the owner of Santa Cruz Olive Tree Nursery, where he grows a wide selection of olive varieties. He was interested in starting an olive oil business but didn’t have enough land of his own. So he and Chris went into business together and, eventually, had a crop to make into olive oil.The first year they entered it in the Los Angeles County Fair, the most important olive oil competition in the United States, it won Best in Show and has won gold medals ever since.

The olive oil business turned out to be a good complement to Chris’s flower business because the heaviest workloads are at different times of year. “I can keep my employees busy from the beginning of spring through November,” she said. “It’s a good match.”

Selling successfully at craft shows requires you to have a product line that stands out from the crowd. This is where your creativity comes into play. Look for innovative containers, or make your own. Don’t read the same publications as everyone else; instead, browse the fresh-flower magazines to find ideas that translate to drieds. For example, a magazine for florists has featured inexpensive glass cylinders covered with twigs of pussy willow; these would make great containers for a dried arrangement.

Crafters disagree about whether it’s cheaper to grow all your own materials or to buy them. Keep track of the time you spend growing, harvesting, and drying your flowers, in order to decide whether you might be better off buying some or even all of your materials. Try buying some things that you can’t grow, and sell them alongside or incorporated with your own product. For example, you may grow plenty of small, filler-type plants but need a big, attention-getting flower for your bouquets. Buying dried roses or peonies might very well give your bouquets the crowning touch that puts them into a much higher price range. Just be sure you’re marking up every purchased flower that you sell.

If you try to sell both fresh and dried flowers, you may meet yourself coming and going. Although the growing of each is the same, the marketing is not. Try to keep good records that will allow you to compare the profit margin on each type of product. Obviously, selling flowers fresh by the bunch is going to be far less labor-intensive than harvesting, drying, storing, and then crafting products. But you must also take into consideration the strength of each market: How much can you sell fresh? How much dried? In addition, you must consider the overall workload on your farm; for example, if your growing season is short and a September frost puts you out of the fresh-flower business, you may need a few months of dried-flower sales in order to make a profit.

Ultimately, the type of flowers you grow can’t be determined solely by arithmetic—you need to take subjective factors into account, too. The most important one, in my opinion, is your own personal enjoyment. If you really love crafting with drieds, then by all means do it! You’ll be happiest at work you enjoy, whether or not it’s the most profitable approach. If, on the other hand, you don’t really like to spend time working with drieds, why bother with it? The first few years that we grew flowers, I made wreaths to sell at farmers’ markets. The wreaths were quite popular, and at $40 each, I made a profit. But I did not enjoy sitting up till midnight, crafting, after working outside all day. As soon as I got a good hold on the fresh-flower market, I stopped doing drieds altogether.