CHAPTER XIV

CHILD LABOR

I HAVE always advised men to read. All my life I have told them to study the works of those great authors who have been interested in making this world a happier place for those who do its drudgery. When there were no strikes, I held educational meetings and after the meetings I would sell the book, “Merrie England,” which told in simple fashion of the workers’ struggle for a more abundant life.

“Boys,” I would say, “listen to me. Instead of going to the pool and gambling rooms, go up to the mountain and read this book. Sit under the trees, listen to the birds and take a lesson from those little feathered creatures who do not exploit one another, nor betray one another, nor put their own little ones to work digging worms before their time. You will hear them sing while they work. The best you can do is swear and smoke.”

I was gone from the eastern coal fields for eight years. Meanwhile I was busy, waging the old struggle in various fields. I went West and took part in the strike of the machinists of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the corporation that swung California by its golden tail, that controlled its legislature, its farmers, its preachers, its workers.

Then I went to Alabama. In 1904 and ’05 there were great strikes in and around Birmingham. The workers of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad were on strike. Jay Gould owned the railroad and thought he owned the workers along with the ties and locomotives and rolling stock The miners struck in sympathy. These widespread strikes were part of the American Railway Union strike, led by Eugene Debs, a railway worker.

One day the governor called Douglas Wilson, the chairman of the strike committee, to his office. He said, “You call this strike off immediately. If you don’t do it, I shall.”

“Governor,” said Douglas, “I can’t call off the strike until the men get the concessions that they struck for.”

“Then I will call out the militia,” said he.

“Then what in hell do you think we will be doing while you are getting the militia ready!”

The governor knew then he had a fight on, for Douglas was a heroic fighter; a fine, open character whom the governor himself respected.

The militia were called out. There was a long drawn out fight. I was forbidden to leave town without permit, forbidden to hold meetings. Nevertheless I slipped through the ranks of the soldiers without their knowing who I was—just an old woman going to a missionary meeting to knit mittens for the heathen of Africa!

I went down to Rockton, a mining camp, with William Malley and held a meeting.

Coming back on the train the conductor recognized me.

“Mother Jones,” he said, “did you hold a meeting in Rockton?”

“I certainly did,” said I.

He reported me to the general manager and there was hell to pay but I kept right on with my agitation. The strike dragged on. Debs was put in jail. The leaders were prosecuted. At last the strike was called off. I was in Birmingham.

Debs was on his way north after being released from jail and the local union arranged a public meeting for him. We rented the opera house and advertised the meeting widely. He was to speak Sunday evening. Sunday afternoon the committee were served with an injunction, prohibiting the meeting. The owner of the opera house was also notified that he would not be allowed to open the doors of his building.

The chairman of the committee on the meeting didn’t have much fighting blood in him, so I told several of the boys to say nothing to him but go over to Bessemer and Pratt, near-by mining towns, and bring a bunch of miners back with them to meet Debs when he got off the train.

At the Union hall a large number of people had gathered to see what was going to happen.

When it was train time, I moved that everyone there go down to the depot to meet Debs.

“I think just the committee on reception should go,” said the chairman, who was strong for form.

“I move that we all form a committee on reception,” said I, and everybody hollered, “Yes! Yes!”

When we got down to the station there were several thousand miners there from Bessemer and Pratt.

The train pulled in and Debs got off. Those miners did not wait for the gates to open but jumped over the railing. They put him on their shoulders and marched out of the station with the crowd in line. They marched through the streets, past the railway offices, the mayor’s office, the office of the chief of police. “Debs is here! Debs is here!” they shouted.

The chief of police had a change of heart. He sent word to me that the opera house was open and we could hold our meeting. The house was jammed, the aisles, the window sills, every nook and corner. The churches were empty that night, and that night the crowd heard a real sermon by a preacher whose message was one of human brotherhood.

When the railroad workers’ strike ended I went down to Cottondale to get a job in the cotton mills. I wanted to see for myself if the grewsome stories of little children working in the mills were true.

I applied for a job but the manager told me he had nothing for me unless I had a family that would work also. I told the manager I was going to move my family to Cottondale but I had come on ahead to see what chances there were for getting work.

“Have you children?”

“Yes, there are six of us.”

“Fine,” he said. He was so enthusiastic that he went with me to find a house to rent.

“Here’s a house that will do plenty,” said he. The house he brought me to was a sort of two-story plank shanty. The windows were broken and the door sagged open. Its latch was broken. It had one room down stairs and unfinished loft upstairs. Through the cracks in the roof the rain had come in and rotted the flooring. Downstairs there was a big old open fireplace in front of which were holes big enough to drop a brick through.

The manager was delighted with the house.

“The wind and the cold will come through these holes,” I said.

He laughed. “Oh, it will be summer soon and you will need all the air you can get.”

“I don’t know that this house is big enough for six of us.”

“Not big enough?” he stared at me. “What you all want, a hotel?”

I took the house, promising to send for my family by the end of the month when they could get things wound up on the farm. I was given work in the factory, and there I saw the children, little children working, the most heartrending spectacle in all life. Sometimes it seemed to me I could not look at those silent little figures; that I must go north, to the grim coal fields, to the Rocky Mountain camps, where the labor fight is at least fought by grown men.

Little girls and boys, barefooted, walked up and down between the endless rows of spindles, reaching thin little hands into the machinery to repair snapped threads. They crawled under machinery to oil it. They replaced spindles all day long, all day long; night through, night through. Tiny babies of six years old with faces of sixty did an eight-hour shift for ten cents a day. If they fell asleep, cold water was dashed in their faces, and the voice of the manager yelled above the ceaseless racket and whir of the machines.

Toddling chaps of four years old were brought to the mills to “help” the older sister or brother of ten years but their labor was not paid.

The machines, built in the north, were built low for the hands of little children.

At five-thirty in the morning, long lines of little grey children came out of the early dawn into the factory, into the maddening noise, into the lint filled rooms. Outside the birds sang and the blue sky shone. At the lunch half-hour, the children would fall to sleep over their lunch of cornbread and fat pork. They would lie on the bare floor and sleep. Sleep was their recreation, their release, as play is to the free child. The boss would come along and shake them awake. After the lunch period, the hour-in grind, the ceaseless running up and down between the whirring spindles. Babies, tiny children!

Often the little ones were afraid to go home alone in the night. Then they would sleep till sunrise on the floor. That was when the mills were running a bit slack and the all-night shift worked shorter hours. I often went home with the little ones after the day’s work was done, or the night shift went off duty. They were too tired to eat. With their clothes on, they dropped on the bed . . . to sleep, to sleep . . . the one happiness these children know.

But they had Sundays, for the mill owners, and the mill folks themselves were pious. To Sunday School went the babies of the mills, there to hear how God had inspired the mill owner to come down and build the mill, so as to give His little ones work that they might develop into industrious, patriotic citizens and earn money to give to the missionaries to convert the poor unfortunate heathen Chinese.

“My six children” not arriving, the manager got suspicious of me so I left Cottondale and went to Tuscaloosa where I got work in a rope factory. This factory was run also by child labor. Here, too, were the children running up and down between spindles. The lint was heavy in the room. The machinery needed constant cleaning. The tiny, slender bodies of the little children crawled in and about under dangerous machinery, oiling and cleaning. Often their hands were crushed. A finger was snapped off.

A father of two little girls worked a loom next to the one assigned to me.

“How old are the little girls?” I asked him.

“One is six years and ten days,” he said, pointing to a little girl, stoop shouldered and thin chested who was threading warp, “and that one,” he pointed to a pair of thin legs like twigs, sticking out from under a rack of spindles, “that one is seven and three months.”

“How long do they work?”

“From six in the evening till six come morning.”

“How much do they get?”

“Ten cents a night.”

“And you?”

“I get forty.”

In the morning I went off shift with the little children. They stumbled out of the heated atmosphere of the mill, shaking with cold as they came outside. They passed on their way home the long grey line of little children with their dinner pails coming in for the day’s shift.

They die of pneumonia, these little ones, of bronchitis and consumption. But the birth rate like the dividends is large and another little hand is ready to tie the snapped threads when a child worker dies.

I went from Tuscaloosa to Selma, Alabama, and got a job in a mill. I boarded with a woman who had a dear little girl of eleven years working in the same mill with me.

On Sunday a group of mill children were going out to the woods. They came for Maggie. She was still sleeping and her mother went into the tiny bedroom to call her.

“Get up, Maggie, the children are here for you to go to the woods.”

“Oh, mother,” she said, “just let me sleep; that’s lots more fun. I’m so tired. I just want to sleep forever.”

So her mother let her sleep.

The next day she went as usual to the mill. That evening at four o’clock they brought her home and laid her tiny body on the kitchen table She was asleep—forever. Her hair had caught in the machinery and torn her scalp off.

At night after the day shift came off work, they came to look at their little companion. A solemn line of little folks with old, old faces, with thin round shoulders, passed before the corpse, crying. They were just little children but death to them was a familiar figure.

“Oh, Maggie,” they said, “We wish you’d come back. We’re so sorry you got hurted!”

I did not join them in their wish. Maggie was so tired and she just wanted to sleep forever.

I did not stay long in one place. As soon as one showed interest in or sympathy for the children, she was suspected, and laid off. Then, too, the jobs went to grown-ups that could bring children. I left Alabama for South Carolina, working in many mills.

In one mill, I got a day-shift job. On my way to work I met a woman coming home from night work. She had a tiny bundle of a baby in her arms.

“How old is the baby?”

“Three days. I just went back this morning. The boss was good and saved my place.”

“When did you leave?”

“The boss was good; he let me off early the night the baby was born.”

“What do you do with the baby while you work?”

“Oh, the boss is good and he lets me have a little box with a pillow in it beside the loom. The baby sleeps there and when it cries, I nurse it.”

So this baby, like hundreds of others, listened to the whiz and whir of machinery before it came into the world. From its first weeks, it heard the incessant racket raining down upon its ears, like iron rain. It crawled upon the linty floor. It toddled between forests of spindles. In a few brief years it took its place in the line. It renounced childhood and childish things and became a man of six, a wage earner, a snuff sniffer, a personage upon whose young-old shoulders fortunes were built.

And who is responsible for this appalling child slavery? Everyone. Alabama passed a child labor law, endeavoring to some extent to protect its children. And northern capitalists from Massachusetts and Rhode Island defeated the law. Whenever a southern state attempts reform, the mill owners, who are for the most part northerners, threaten to close the mills. They reach legislatures, they send lobbies to work against child labor reform, and money, northern money for the most part, secures the nullification of reform laws through control of the courts.

The child labor reports of the period in which I made this study put the number of children under fourteen years of age working in mills as fully 25 per cent of the workers; working for a pittance, for eight, nine, ten hours a day, a night. And mill owners declared dividends ranging from 50 per cent to 90.

“Child labor is docile,” they say. “It does not strike. There are no labor troubles.” Mill owners point to the lace curtains in the windows of the children’s homes. To the luxuries they enjoy. “So much better than they had when as poor whites they worked on the farms!”

Cheap lace curtains are to offset the labor of children! Behind those luxuries we cannot see the little souls deadened by early labor; we cannot see the lusterless eyes in the dark circle looking out upon us. The tawdry lace curtains hang between us and the future of the child, who grows up in ignorance, body and mind and soul dwarfed, diseased.

I declare that their little lives are woven into the cotton goods they weave; that in the thread with which we sew our babies’ clothes, the pure white confirmation dresses of our girls, our wedding gowns and dancing frocks, in that thread are twisted the tears and heart-ache of little children.

From the south, burdened with the terrible things I had seen, I came to New York and held several meetings to make known conditions as I had found them. I met the opposition of the press and of capital. For a long time after my southern experience, I could scarcely eat. Not alone my clothes, but my food, too, at times seemed bought with the price of the toil of children.

The funds for foreign missions, for home missions, for welfare and charity workers, for social settlement workers come in part, at least, from the dividends on the cotton mills. And the little mill child is crucified between the two thieves of its childhood; capital and ignorance.

“Of such is the kingdom of Heaven,” said the great teacher. Well, if Heaven is full of undersized, round shouldered, hollow-eyed, listless, sleepy little angel children, I want to go to the other place with the bad little boys and girls.

In one mill town where I worked, I became acquainted with a mother and her three little children, all of whom worked in the mill with me. The father had died of tuberculosis and the family had run up a debt of thirty dollars for his funeral. Year in and year out they toiled to pay back to the company store the indebtedness. Penny by penny they wore down the amount. After food and rent were deducted from the scanty wages, nothing remained. They were in thralldom to the mill.

I determined to rescue them. I arranged with the station agent of the through train to have his train stop for a second on a certain night. I hired a wagon from a farmer. I bought a can of grease to grease the axles to stop their creaking. In the darkness of night, the little family and I drove to the station. We felt like escaping negro slaves and expected any moment that bloodhounds would be on our trail. The children shivered and whimpered.

Down the dark tracks came the through train. Its bright eye terrified the children. It slowed down. I lifted the two littlest children onto the platform. The mother and the oldest climbed on. Away we sped, away from the everlasting debt, away to a new town where they could start anew without the millstone about their necks.

When Pat Dolan was president of the Pittsburgh miners’ union, and there never was a better president than Pat, he got permission from the general managers of the mines for me to go through the district and solicit subscriptions for The Appeal to Reason. The managers must have thought the paper some kind of religious sheet and that I was a missionary of some sort.

Anyway, during those months, I came into intimate contact with the miners and their families. I went through every mine from Pittsburgh to Brownsville. Mining at its best is wretched work, and the life and surroundings of the miner are hard and ugly. His work is down in the black depths of the earth. He works alone in a drift. There can be little friendly companionship as there is in the factory; as there is among men who built bridges and houses, working together in groups. The work is dirty. Coal dust grinds itself into the skin, never to be removed. The miner must stoop as he works in the drift. He becomes bent like a gnome.

His work is utterly fatiguing. Muscles and bones ache. His lungs breathe coal dust and the strange, damp air of places that are never filled with sunlight. His house is a poor makeshift and there is little to encourage him to make it attractive. The company owns the ground it stands on, and the miner feels the precariousness of his hold. Around his house is mud and slush. Great mounds of culm, black and sullen, surround him. His children are perpetually grimy from play on the culm mounds. The wife struggles with dirt, with inadequate water supply, with small wages, with overcrowded shacks.

The miner’s wife, who in the majority of cases, worked from childhood in the near-by silk mills, is overburdened with child bearing. She ages young. She knows much illness. Many a time I have been in a home where the poor wife was sick in bed, the children crawling over her, quarreling and playing in the room, often the only warm room in the house.

I would tidy up the best I could, hush the little ones, get them ready for school in the morning, those that didn’t go to the breakers or to the mills, pack the lunch in the dinner bucket, bathe the poor wife and brush her hair. I saw the daily heroism of those wives.

I got to know the life of the breaker boys. The coal was hoisted to a cupola where it was ground. It then came rattling down in chutes, beside which, ladder-wise, sat little breaker boys whose job it was to pick out the slate from the coal as the black rivers flowed by. Ladders and ladders of little boys sat in the gloom of the breakers, the dust from the coal swirling continuously up in their faces. To see the slate they must bend over their task. Their shoulders were round. Their chests narrow.

A breaker boss watched the boys. He had a long stick to strike the knuckles of any lad seen neglecting his work. The fingers of the little boys bled, bled on to the coal. Their nails were out to the quick.

A labor certificate was easy to get. All one had to do was to swear to a notary for twenty-five cents that the child was the required age.

The breaker boys were not Little Lord Fauntleroys. Small chaps smoked and chewed and swore. They did men’s work and they had men’s ways, men’s vices and men’s pleasures. They fought and spit tobacco and told stories out on the culm piles of a Sunday. They joined the breaker boys’ union and beat up scabs. They refused to let their little brothers and sisters go to school if the children of scabs went.

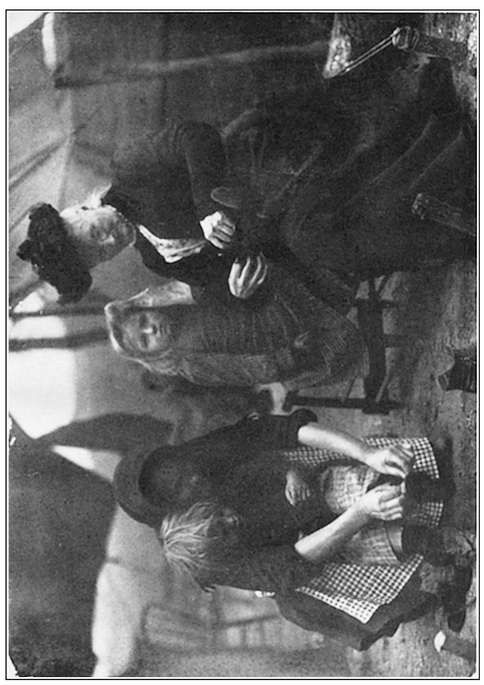

Mother Jones with the Miners’ Children

In many mines I met the trapper boys. Little chaps who open the door for the mule when it comes in for the coal and who close the door after the mule has gone out. Runners and helpers about the mine. Lads who will become miners; who will never know anything of this beautiful world, of the great wide sea, of the clean prairies, of the snow capped mountains of the vast West. Lads born in the coal, reared and buried in the coal. And his one hope, his one protection—the union.

I met a little trapper boy one day. He was so small that his dinner bucket dragged on the ground.

“How old are yon, lad?” I asked him.

“Twelve,” he growled as he spat tobacco on the ground.

“Say son,” I said, “I’m Mother Jones. You know me, don’t you? I know you told the mine foreman you were twelve, but what did you tell the union?”

He looked at me with keen, sage eyes. Life had taught him suspicion and caution.

“Oh, the union’s different. I’m ten come Christmas.”

“Why don’t you go to school?”

“Gee,” he said—though it was really something stronger—“I ain’t lost no leg!” He looked proudly at his little legs.

I knew what he meant: that lads went to school when they were incapacitated by accidents.

And you scarcely blamed the children for preferring mills and mines. The schools were wretched, poorly taught, the lessons dull.

Through the ceaseless efforts of the unions, through continual agitation, we have done away with the most outstanding evils of child labor in the mines. Pennsylvania has passed better and better laws. More and more children are going to school. Better schools have come to the mining districts. We have yet a long way to go. Fourteen years of age is still too young to begin the life of the breaker boy. There is still too little joy and beauty in the miner’s life but one who like myself has watched the long, long struggle knows that the end is not yet.