homsky is reluctant to talk about his life. “I’m rather against the whole notion of making public personalities, of having some people be stars and all that,” he says. Cults of personality distract people from real issues. The media are so absorbed with these public personalities, that “air time” is almost totally dominated with gossip, the details of hideous violent crimes, or sports. There is little information about anything you can do anything constructive about, including most of what your government is doing.

homsky is reluctant to talk about his life. “I’m rather against the whole notion of making public personalities, of having some people be stars and all that,” he says. Cults of personality distract people from real issues. The media are so absorbed with these public personalities, that “air time” is almost totally dominated with gossip, the details of hideous violent crimes, or sports. There is little information about anything you can do anything constructive about, including most of what your government is doing.

But though Chomsky may feel that the biographical details of his life are a distraction from the pressing issues that he wants to discuss, others are irresistibly curious about the lives of the originators of great ideas. Therefore we will take a quick look. But in deference to the man, we won’t spend very long on the subject.

vram Noam Chomsky was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, on December 7, 1928. One of two sons, Chomsky was a child during Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in 1929 and lasted until World War II. The Chomsky family was spared the worst aspects of the Depression because both parents had Jobs. The effects of the crisis were still profound, however, and Chomsky says that some of his earliest memories are Depression scenes: people selling rags at the door, police violently breaking strikes, and so on.

vram Noam Chomsky was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, on December 7, 1928. One of two sons, Chomsky was a child during Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in 1929 and lasted until World War II. The Chomsky family was spared the worst aspects of the Depression because both parents had Jobs. The effects of the crisis were still profound, however, and Chomsky says that some of his earliest memories are Depression scenes: people selling rags at the door, police violently breaking strikes, and so on.

The family was deeply involved in Jewish culture, the Zionist movement, and the revival of the Hebrew language.

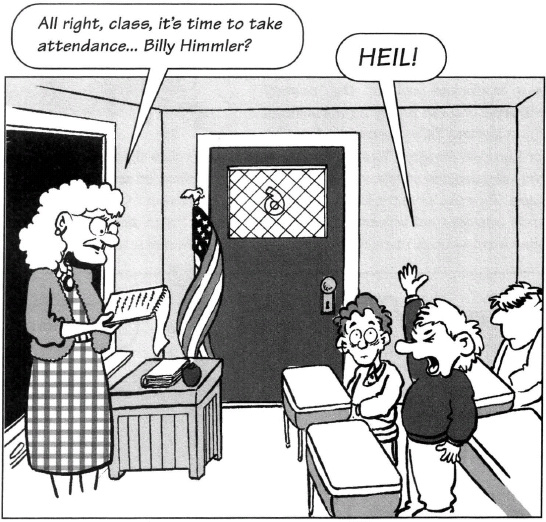

His family was practically the only Jewish family in a bitterly anti-Semitic Irish and German Catholic neighborhood where there was open support for the Nazis until the U.S. entered World War II. Chomsky was exposed fascism in Europe during the ’30s.

His first published piece of writing was an editorial for his school newspaper about the fall of Barcelona. At the age of 12 he wrote a history of the Spanish Civil War.

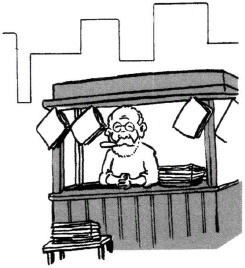

The Kiosk

He often visited an uncle in New York City who operated a magazine kiosk at the subway exit at 72nd and Broadway. Chomsky says his uncle was a hunchback with a background in “crime and left-wing politics.” Because of his disability, he qualified to operate a kiosk. It was at the less trafficked exit of the subway entrance and did poorly as a business, but in the late ’30s it became a hangout for European emigres. Young Chomsky spent many hours there participating in lively discussions of issues and ideas that took place on an almost ongoing basis. Chomsky says the kiosk was where he received his political education. His uncle was also well-versed in the work of Sigmund Freud, and Chomsky developed a broad understanding of Freudian theory while still a teenager.

Chomsky has described an experience that affected him deeply in which a bully was picking on “the standard fat kid,” and everyone supported the bully while no one came to the aid of the victim.

“I stood up for him for a while,” he says. “Then I got scared.” Afterwards he was ashamed and resolved that in the future he would support the underdog, those unjustly oppressed. “I was always on the side of the losers,” he said, “like the Spanish anarchists.”

Though Chomsky is known for his intellect, his political ideas are driven more by moral principles. He was appalled by the way people taunted German prisoners through the barbed wire at a prison camp near his high school as though it was the patriotic thing to do to. At the same time, Chomsky was much more passionately opposed to Nazism than the people who were taunting the soldiers.

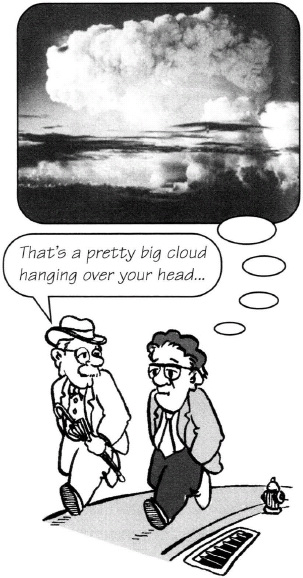

On the day of the Hiroshima bombing, says Chomsky, “I literally couldn’t talk to any one. There was nobody. I just walked off by myself … I could never talk to anyone about it and never understood anyone’s reaction.” [CR]

College Dropout

To manage the expense of college, he commuted several hours a day to attend the university while living at home. He also worked as a Hebrew teacher evenings, afternoons, and Sundays. But his enthusiasm for the university waned. He lost interest in every subject he enrolled in. After two years, he decided to drop out. But he maintained his lifelong interest in radical politics and became even more deeply involved in Zionism activities. Many years later, in upholding many of the same principles, he would be called anti-Zionist.

Chomsky considered going to Palestine to help to further Arab-Jewish cooperation within a socialist framework. But he was put off by the “deeply anti-democratic” concept of a Jewish state.

Under Harris’ influence, Chomsky returned to college and studied linguistics. He calls his university experience “unconventional.” The linguistics department was a small group of graduate students who shared political and other interests and met in restaurants or in Harris’ apartment for all-day discussion sessions. Chomsky immersed himself in linguistics, philosophy, and logic. He was awarded BA and MA degrees though he had very little contact with the university system. He married linguist Carol Schaz in 1949. They were to have a son and two daughters.

One of Chomsky’s philosophy teachers was Nelson Goodman, who introduced him to the Society of Fellows at Harvard. He was admitted in 1951 and awarded a stipend, which freed him for the first time in his life from the necessity to work outside of his research.

Chomsky and his wife considered going back to live on the kibbutz. He had no hopes or interest in an academic career and nothing holding him in the United States. But he was uncomfortable with the conformism and the racist principles underlying the institution. Chomsky had been opposed to the formation of a Jewish state in 1947-48 because he felt the socialist institutions of the pre-state Jewish settlement in Palestine would not survive the state system.

When his term at Society of Fellows was scheduled to end in 1954 he had no job prospects, so he asked for an extension. His wife had gone back to the kibbutz for a longer visit and the two planned to return to stay. Instead Chomsky received a research position at M.I.T. and became immersed in linguistics.

Political activism

In the 1960’s the escalation of the Vietnam war forced Chomsky to make a moral choice. He began active resistance to the war knowing that it was very likely that he would have to spend time in prison for it. He put a very comfortable position in academia in jeopardy to protest the war. Asked about why he took that risk, Chomsky has said, “It has to do with being able to look yourself in the eye in the morning.”

“Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions. In the Western world at least, they have the power that comes from political liberty, from access to information and freedom of expression. For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology, and class interest through which the events of current history are presented to us…

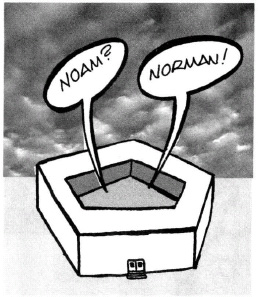

In October 1967, Chomsky participated in the demonstrations that took place at the Pentagon and the Justice Department and was one of many who were jailed. Norman Mailer, who shared a cell with Chomsky described him in The Armies of the Night, as “a slim, sharp-featured man with an ascetic expression and an air of gentle but absolute moral integrity.”

Since making the commitment to be politically active in the late ‘60s, Professor Chomsky has written a steady stream of books, articles, and pamphlets expressing his views. He appears almost anywhere he is invited to speak or discuss his views. In the meantime, he remains a professor of linguistics at MIT.

Despite the variety of his interests and pursuits, Chomsky’s approach is amazingly consistent. He applies the same ruthlessly honest logic to every-thing he examines. He did not, however, spring forth fully formed, fully “Chomskian. ”

As with any important thinker, Chomsky’s system of ideas rests on the work of many fine thinkers who preceded him.

we’ll have a look at some of the more notable ones.