What is linguistics?

inguistics is the science of language. In using language, people employ principles of grammar, the complex and subtle rules of language use, without having to consciously know the principles. Part of the work of linguistics is to discover or establish those principles.

inguistics is the science of language. In using language, people employ principles of grammar, the complex and subtle rules of language use, without having to consciously know the principles. Part of the work of linguistics is to discover or establish those principles.

Another part of the work of linguistics is to compare and contrast languages, their grammars, pronunciations, how meaning is created and how the languages are used. As with other studies, early biology for example, a preliminary part of the task is naming and classification.

Modern linguistics emerged as a distinct field of study in the 19th Century while colonialism was flourishing, world travel was increasing, and European cultures were encountering other cultures and languages. Linguists made an effort to study the languages that they were encountering, in many cases languages that were disappearing under the pressure of colonialism. Experts in linguistics have often been called upon to ease confrontations between cultures by helping people to learn foreign languages as quickly as possible.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Evolution of linguistics

In the West, the study of language began with the Greeks. For plato it was a study of the etymologies or origins of Greek words. Dionysius Thrax, in the 1st Century BC., worked out an elaborate system of grammar for the Greek language. It became known as traditional grammar.

Roman grammarians Aelius Donatus and priscian in the 6th Century AD. adopted Dionysius Thrax’s system and adapted it to Latin. It worked well because the two languages are both Indo-European languages, related in lineage and structurally similar.

The Greeks philosophical grammar was passed onto the Romans. The Graeco-Roman tradition extended into Medieval times when it was applied to the modern European languages. When Latin branched into the Romance languages—Italian, French, and Spanish—the languages had become structurally different and required different kinds of analysis. It became difficult to apply the traditional grammar.

Some scholars saw the changes as a corruption of classical Latin and urged return to the archaic language forms. The idea that language change is corruption and should be prevented is called linguistic prescriptivism.

With the 15th century exploration of trade routes and colonization, Europe was exposed to other languages not descended from Latin or Greek and not subject to the same traditional grammar. This stimulated a search for principles that would apply to the broadened frame of reference of languages.

The search for canons of a universal logic led to the so-called general grammars of the 17th Century.

With the discovery of the New World, grammatical analysis was extended to non–European languages, but was relatively unproductive because all the languages were forced into the Latin mold. It was when the English discovered the methods of the Indian scholar Panini ( c. 4th century B.C.) that modern linguistics began. Panini provided a new view of language and grammatical description.

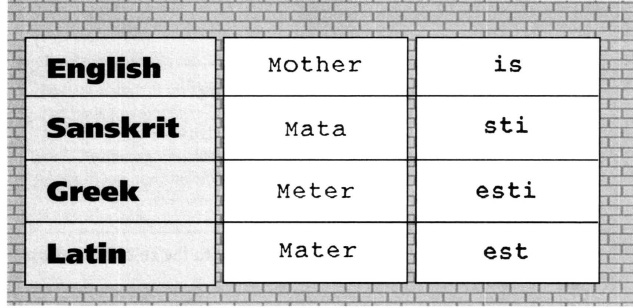

The English colonists in India in the 18th Century discovered Sanskrit, an ancient language of religion, philosophy, and literature (now classified as an Indo-lranian language). The Hindus held Sanskrit in esteem the way Europeans did Latin. Linguists saw a resemblance between Sanskrit and Greek and Latin.

Specific words are similar, as are the organization of morphology and syntax.

morphology: form and structure of language

syntax: the way words are put together to form phrases, clauses, sentences...

Hindus had studied the grammar of Sanskrit for three millennia and their work in many respects went beyond the traditional grammar of the west in terms of philosophical consistency and analytic thoroughness. The sacred texts of India, the vedas, were studied grammatically by tradition and the tradition was compiled by Panini, the precursor of modern linguistics.

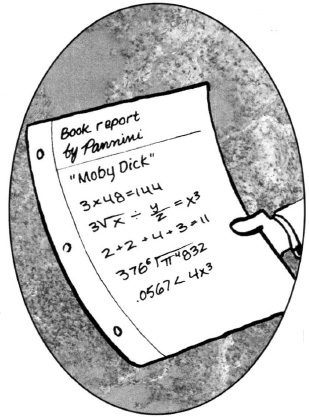

He based his statements on the direct observation of the actual texts he analyzed, and he expressed them in quasi mathematical symbols. Panini’s Sanskrit grammar became the model for European linguists. In may aspects his methods have not been improved upon since.

European scholars sought an explanation for the similarity of Sanskrit to Latin and Greek. Sir William Jones, considered the first great European scholar of Sanskrit, suggested in 1786 that the three languages may all “have sprung from some common source which, perhaps, no longer exists.”

Jones’ insight defined the area of study for linguists of the next 100 years. Nineteenth Century linguistics was primarily historical and comparative, as scholars looked for cross-connections and evolutionary links between Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Germanic, Celtic and other Indo-European languages.

Toward the end of the 19th Century, linguists began to turn their attention from the history and evolution of language to its organization and function. This branch of study became known as synchronic linguistics, the study of the language now, as opposed to historical or diachronic linguistics. It was exemplified in the work of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure in his Course in General Linguistics, published posthumously in 1916. The two analytic modes remain today as complementary aspects of the study of linguistics.

During the 1920s synchronic linguistics in America was stimulated by study of a rich variety of Native American languages. Major linguists of the time, such as Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, and Alfred L. Froeber, were also social anthropologists. In the early 1930s, linguists turned from descriptive work to a search for theoretical foundations. Leonard Bloomfield, a Behaviorist, laid down tenets of American linguistic thought in 1933 in his book Language.

Bloomfield’s behaviorist model was refined in the generation that followed by such linguists as Bernard Bloch, zellig Harris, Charles Hockett, Eugene Nida, and Kenneth Pike, who developed a theory of language analysis known as neo-Bloomfieldian or structural linguistics, called American structuralism to distinguish it from other branches called structural.

Behaviorism limited its field of inquiry to physically measurable phenomena, in an effort to emulate the physical sciences. Meaning, therefore, was not a part of the domain of the structuralists. In the early 1950s, however, Zellig Harris of the University of pennsylvania began a series of studies that led to the development of techniques for the scientific study of meaning, and to a revolution in linguistics. He extended structuralist analysis beyond the sentence and developed formulas to capture systematic linguistic relationships between different kinds of sentences. He called his formulas transformations.

I was a student of Harris. I incorporated the concept of transformation into a theory now called TRANSFORMATIVE-GENERATIVE LINGUISTICS, or simply GENERATIVE LINGUISTICS. The theory breaks off from structuralism in that it synthesizes theoretical and methodological elements from mathematics and the philosophy of language. I rebelled against behaviorism, taking a neo-rationalist stance which recalls the 17th Century concept of general grammar.

The concept of transformations gave linguistics a powerful descriptive and analytic tool, and dropping the narrow limitations of Behaviorist doctrine opened a broad area for inquiry. Between 1960 and 1980, generative linguistics ascended and structuralism declined.

Linguistics as a science

Traditionally linguists studied the differences and similarities of languages in their pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, and relationships between speakers. They created a vocabulary for the study of language which could be used by people in other fields who have an interest in language, such as lexicographers, speech therapists, translators and language teachers. Chomsky wanted linguistics to be “a real science.”

It has long been a disputed point whether or not the social sciences, studies of people, can really be called sciences. B.F. Skinner tried to apply a scientific point of view to the study of psychology, but by Chomsky’s evaluation he failed because he attempted to deal with human beings as though they were equivalent to inanimate objects.

Chomsky’s way of bringing science into humanistic studies would be not to view humans as equivalent to the objects of study of the physical sciences, but to adopt scientific methods of analysis and logic.

In his search for explanatory principles, Chomsky focused more on similarities between languages than on differences. He also narrowed his focus to English and well-studied languages rather than branching out and cataloging many obscure languages. Chomsky felt that science must make an attempt to explain why things function the way they do. Though many reject the idea that human behavior can be the subject of a scientific study, for Chomsky seeking solutions to problems, trying to find answers to the question “why?” is what characterizes science.

Chomsky used the science of physics as a model for how he envisioned linguistics. The relevant characteristics are:

1. It is important to seek explanations and not just descriptions and classifications.

2. Narrowing the field of study can lead to more firmly established theories though at a sacrifice to more far-reaching answers.

3. The use of abstraction and idealization constructs models that can be accorded a greater degree of reality than sensory data.

According to Chomsky, the central nervous system and cortex are biologically programmed not only for the physiological aspects of speech but also for the organization of language itself. The capacity for organizing words into relationships of words to each other is inherent.

The ordinary use of language, says Chomsky, is creative, innovative, and more than merely a response to a stimulus, as the Behaviorist model suggests. [see Behaviorism]

Universal Generative Grammar

Chomsky determined that there is a universal grammar which is part of the genetic birthright of human beings, that we are born with a basic template for language that any specific language fits into. This unique capacity for language is, as far as we know, unique to the human species and ordinary use of language is evidence of tremendous creative potential in every human being.

The remarkable ability of human children to rapidly learn language in their infancy when they still have little outside experience or frame of reference upon which to base their understanding, leads Chomsky to believe that not only the capacity for language, but a fundamental grammar is innate from birth.

It is relatively certain, says Chomsky, that people are not genetically programmed for a specific language, so that a Chinese baby growing up in United states will speak English and an American child surrounded by people speaking Chinese will learn to speak Chinese. From this fact, says Chomsky, it follows by logic that there is a universal grammar which underlies the structure of all languages. Chomsky went on to formulate rules for this grammar. Employing a system of symbols, these formulations became increasingly like mathematical operations.

Evidence that Universal Grammar Is Innate

Chomsky says that certain rules of grammar are too hidden, too complex to be figured out by children who have so little evidence to go on. These skills are innate, he says, because they cannot have been learned. Children do not have enough evidence to piece together so complicated a system as grammar, to quickly learn to improvise sure-footedly within the system of grammar while rarely being told what the underlying rules are and rarely being given examples of incorrect grammar.

Language acquisition is distinguished by linguists from language learning. Learning a language later in life, after the developmental stage of language acquisition has played out, is much like other kinds of learning. Language students get books of grammar and vocabulary, take classes, are instructed and drilled by teachers. Young children who have never spoken before absorb language with great rapidity and with the minimum of cues from the outside world. The process of acquisition is akin to imprinting, an innate process which begins to play out along certain lines when it is triggered by outside stimuli.

When a bird hatches from its shell at birth and forms a parent/young bond with the first large organism it sees, it is called imprinting. It is a behavior that is triggered by some outside stimulus, but plays itself out in a standard, predictable way, and is the same from one individual to the next.

The question of nature versus nurture, of what is inherited genetically versus what is acquired through experience and environmental influences, is an old one. These categories cannot be clearly separated. They seem to blend together as they play out in the real world. So the controversy will probably never be clearly resolved. The behaviorist doctrine says that all behavior is learned and that human beings are a blank slate at birth and can be manipulated and molded to acquire almost any sort of behavior.

To Chomsky, this would be almost criminally simplistic and inconsistent with the facts. Language is exceedingly complex and yet is mastered easily in a very short time by human children who begin with no frame of reference at all and rarely receive any degree of formal instruction. The only evidence they have to work with is hearing people talk. They are rarely told why the sentences are correct or given examples of what would be incorrect. And yet they launch into the fluent usage of a system that includes a large number of very complex principles of grammar, principles Chomsky says they have not received enough evidence to learn about. Chomsky establishes that it would not be possible for these principles to be learned with the evidence that is available to the child.

Two points that you surely noticed, but just in case you didn’t:

1. Chomsky’s view of humanity is startlingly positive: “[the] ordinary use of language is evidence of tremendous creative potential in every human being.”

2. Chomsky’s special genius in both linguistics and politics is his ability to see the clear, simple truth of things. Chomsky is the guy who notices that the Emperor isn’t wearing any clothes. That’s why he appeals to so many of us.

Is Grammar Learnable?

By analyzing subtle grammatical rules that are far beyond the awareness of the average speaker of English, Chomsky shows that the rules we are fluent in are too difficult to have figured out with the evidence we are given as children first learning to speak. Even trying to understand an explanation of how anaphors* (A linguist’s term for a commonly-used but difficult-to-explain “binding” grammatical structure) work is difficult, and yet rarely is the mistake made in the language usage of ordinary people.

*Editor’s note: As if to prove Chomsky’s point, the explanation of anaphors was so difficult, that out of mercy for the lay reader, we’ve decided to leave it out.

It is difficult for a professional linguist to merely list, after the fact, all of the grammatical subtleties that go into making an acceptable or well-formed sentence, especially since the number of possible combinations seems limitless—some sentences are ambiguous, some are not; some are connected to others by paraphrases, implicational relations and so forth. Studying a simple paragraph yields a rich system of inter-relationships and cross-connections that are all consistent with a very subtle system of grammar.

Most sentences that are mathematically possible are clearly ungrammatical, and yet to pinpoint the reason for the unacceptability of a certain form, in many cases, is extremely difficult.

I repeat: Is grammar learnable?

The Study of Learning

To study learning, says Chomsky, we must look at the input (data) and output (grammar) in the organism (child). A child who has no knowledge of language to start with constructs a working knowledge of a language based on certain data. From the relationship of the input/data to the output/grammar, we may begin to develop some idea of the mental activities of the organism, the transition from input to output.

In order to account for the kinds of grammatical rules used in simple sentences, we have to postulate abstract structures that have no direct connection with the physical facts (data) and can only be reasoned from those facts by long chains of highly abstract mental operations.

How do we know that we can say (for example), “What box did Margaret keep the necklace in?” but not ̴What box did Margaret keep the necklace that was in?” It is a property of English, and probably all languages, that some complex noun phrases, like “the necklace that was in the box,” cannot be kept intact when you change a statement to a question. Chomsky says this is a linguistic universal, but is unlearnable from the evidence. When we are learning the language, we are not given enough evidence from which to draw this conclusion.

If we analyze these processes carefully, says Chomsky, we find that the picture does not fit the stimulus-response model of how learning takes place, the blank-slate model of the human organism as portrayed by the Behaviorists. The stimulus-response theory can only lead to a system of habits, a network of associations. And such a system will not account for the sound-meaning relation that all of us know intuitively when we have mastered our language.

The grammars that we use are creative in that they generate, specify, or characterize, a virtually infinite number of sentences. A speaker is capable of using and understanding sentences that have no physical similarity — no point-by-point relationship — to any sentence he has ever heard.

The Infinite Variety of Language

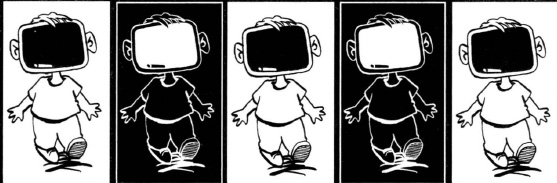

An interesting experiment in this regard was conducted by Richard Ohmann, a professor at Wesleyan University. He showed 25 people a simple cartoon and asked them to describe in one sentence what was going on in the picture. All 25 responses were different. Next the professor put his results into a computer program designed to determine how many grammatically correct sentences could be generated from only the words used in those 25 sentences. The result was 19.8 billion different possibilities.

Other computer calculations have shown that it would take 10 trillion years — 2,000 times the estimated age of the earth — to say all of the possible sentences in English that use exactly 20 words. From this it would be highly unlikely that any 20-word sentence you hear has ever been spoken before, and similar calculations could be made for sentences of different lengths. The number of creative possibilities within the grammar, then, is virtually infinite. And yet, when a fundamental principle of grammar is violated, the speaker does not have to run through a complicated series of analyses to figure it out. He knows instantly.

From an analysis of the input-output relationship of a speaker, it would not be possible for a human being to deduce the subtle and complex rules of the grammar he uses with such authority.

Universal grammar, that set of properties common to any natural language by biological necessity, is a rich and highly articulated structure with explicit restrictions on the kinds of operations that can occur, though it is easy enough to imagine ways we could violate them. Applying purely mathematical operations to sentences, we could come up with any number of possibilities, like reversing the word order of an entire sentence, or switching the last word and the first, which would not yield grammatical sentences. But this does not occur in natural languages. No language constructs a question by simply reversing the order of a declarative sentence, but why not? It would seem to be a simple and obvious solution to the problem, much simpler than the systems that are actually used.

What is the nature of the original state?

Or what is human nature?

A bird does not have to be taught to sing a specific kind of call, or to know when it is time to migrate for the winter. There are many specific behaviors which emerge developmentally but cannot be attributed to learning in the sense that we usually use the term. Walking is an example. Almost all human children without certain relatively rare disabilities learn to walk within the first two years of their lives. The way this behavior is acquired also plays out in familiar and standard ways, from moving the limbs to slithering to crawling to standing while holding and so forth.

Human beings do not have to be taught to cry when they are sad or to laugh when it is appropriate. Sexual behavior also plays out its development in fairly standard and predictable patterns. It is not observable at birth, but unfolds at the appropriate time according to what must be a pre-determined plan that exists within the organism from birth.

In this connection, the word “programmed” is often applied, perhaps misleadingly. “Programmed” is an active verb and raises the question who or what is taking the action; who has done the programming. This is another realm entirely and not part of Chomsky’s discussion. It is also a particularly contemporary metaphor that draws parallels between humans and computers which may or may not be valid and may be objectionable to some who believe that the activity of computers is fundamentally and qualitatively different from the behavior of sentient beings. Without delving into the source of this genetic material, the instinctual programs that play themselves out in the development of the child, Chomsky attempts to establish by logic that these behaviors in humans are not learned but are innate.

Chomsky comes to his conclusion not primarily by observation, but by logic. Observation is the source of the basic elements of the discourse, such as the observation of how children learn language from extremely limited information, but Chomsky’s main contribution follows from the logical processes that he applies to those observations, the questions he asks, the chains of deduction he follows, and his conclusions.

There are other areas of human activity that might be investigated in similar ways as part of looking into the essence of what it means to be human. Human expressions in music and the arts, in religion, ethics, social structures seem also to have their universal qualities which express themselves in various, but remarkably similar ways in diverse cultures around the world.

Chomsky on Skinner and Behaviorism

Skinner’s Behaviorism is one area where Chomsky’s views on linguistics and his political views clearly come together.

Skinner claims that human beings are blank slates, totally controlled by outside influences, their conditioning. He takes will from the individual and replaces it in the environment.

He says: “As a science of behavior adopts the strategy of physics and biology, the autonomous agent to which behavior has traditionally been attributed is replaced by the environment -- the environment in which the species evolved and in which the behavior of the individual is shaped and maintained.” [B.F. Skinner, Beyond Freedom and Dignity]

...and terminates Skinner in the plainest imaginable English:

“For Skinner’s argument to have any force, he must show that people have will, impulses, feelings, purposes, and the like no more than rocks do. If people differ from rocks in this respect, then a science of human behavior will have to take account of this fact.” [FRS]

Chomsky has contributed greatly to refuting Behaviorism’s ugly assertion that we are merely dull machines shaped by a history of reinforcement, exactly as free as rats in a maze, with no intrinsic needs other than physiological satiation.

Chomsky leans strongly toward the belief that human beings are not only born with an innate knowledge of grammar, but that we are also inclined by nature toward free creative inquiry and productive work.

Whether we live up to Chomsky’s view of ourselves or down to Skinner’s depends largely on whether we believe the lies we are told, or find ways to see through them.

If we don’t see through them, we will be exactly as free as rats in a maze.

Which brings us to Chomsky’s study of the media...