CHAPTER 11

BMigrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi

Zebediela is an area in the Limpopo province, situated approximately 40 kilometres south-east of Mokopane (previously known as Potgietersrus). It is home to ethnically mixed communities consisting primarily of Northern Ndebele and Northern Sotho/Pedi people under the Kekana-Ndebele chieftaincy.1 The chiefdom of Zebediela existed as an autonomous polity until 1885 when it was beaconed off and demarcated as a ‘native location’ by the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR).2 In the years before it was reduced to a native location, however, groups of male migrants from this chiefdom had been travelling hundreds of kilometres on foot to white settlements further south, where they engaged in wage labour. With their earnings, they paid colonial taxes and bought guns, which were required to safeguard the independence of their chiefdom. In 1879, the Native Commissioner for the district described Zebediela as ‘rich and well-to-do’ and lamented the fact that none of the young men from this chiefdom would work elsewhere, other than at the diamond fields (Kimberley) where they earned higher wages.3 By the early twentieth century, however, the wages had been depressed and the flood of young men to the diamond fields turned into a trickle.

In 1917, entrepreneur and financier IW Schlesinger purchased a massive tract of land on the southern side of the location and immediately commenced with the establishment of the Zebediela Citrus Estates. Consequently, many people were dispossessed of their land and turned into wage labourers. The largest undertaking of its kind in the southern hemisphere, the development of the Zebediela Citrus Estate (starting in 1918) and the damming of the Gompies River (Nkumpi), which served as a major source of water for the communities and their livestock downstream, caused massive displacement and disruption of people’s livelihoods in the location.4 Within a decade of the citrus estate’s establishment, the supply of labour, according to the estate management’s reports, had become so plentiful that many from the Zebediela location itself accepted wages as low as 25 shillings per month, excluding provisions.5 However, as the South African economy moved from a period of depression to one of rapid growth in the 1930s, the demand and competition for labour increased accordingly and migrants from the location once again pursued the more well-paid labour markets of the Witwatersrand (also referred to as the Rand or Reef).6 As the shortage of arable land escalated, large sections of rural communities became increasingly dependent on migrants’ remittances. Consequently, the flow of migrant labourers from the location to the Rand increased during the 1930s and in the decades that followed.

Although the people of Zebediela location have a long history of involvement in the migrant labour system, very little sustained research has been conducted on migrants from this area – the different employment trajectories that they followed, their networks and the types of collective identities that they developed in urban centres. In South African scholarship generally, a limited number of works have been produced on the histories of migrant networks, but most of them lie hidden in a series of local or regional studies. This chapter looks at patterns of migrancy and collective identities developed by migrants from Zebediela working on the Rand from the 1930s to the 1970s. Using a combination of archival material and oral sources, it looks firstly at how migrants from Zebediela became involved in promoting a sense of Ndebele-ness from the bottom up, by establishing bodies that looked after their interests at home and in towns between the 1940s and 1950s. Secondly, it explores these migrants’ shifting identities and the growing salience of Ndebele ethnicity among them in the context of surrounding ‘homeland’ politics in the 1960s and 1970s. The argument of this chapter revolves around the centrality of collective identities in safeguarding migrants’ interests. While, in the early period, Zebediela migrants on the Rand established a variety of burial societies plus an organisation that sought to resist the state’s interference in their rural homes, by the 1960s and 1970s, many saw their identities primarily in ethnic terms and played a key role in ethnic organisations that agitated for a separate Ndebele ‘homeland’.

Burial societies, migrant associations and betterment schemes, 1930s–1950s

By the 1930s and 1940s, the migrant labour system dominated the economy of the Zebediela area. As in neighbouring Sekhukhuneland further east, villagers with access to land habitually planted crops, but a constellation of inadequate amounts of arable land, an unpredictable climate and distances from major markets made it hard for farming to play a central role as a source of food and cash earnings for the villagers.7 The landless villagers had extremely limited choices: some moved as family units to nearby white farms where they entered into various forms of labour contract – including labour tenancy – but an increasing number of men from the location joined their counterparts from other reserves on their way to the burgeoning towns on the Reef. Most of the Zebediela migrants arrived here in clusters and took up contracts of between six months to a year and sometimes longer on the Rand mines. Many went to mines such as Cullinan Premier Mines (east of Pretoria), East Rand Premier Mines (ERPM) and Simmer and Jack in Germiston, where the majority worked as unskilled or general workers. Those migrants with some level of literacy – thanks to the existence of a number of primary schools situated in Christian villages (called setaseng, after mission stations) established adjacent to ‘traditionalist’ villages – quite possibly found employment as mine clerks or occupied other semi-skilled positions. These migrants were invariably accommodated in mine compounds and had little or no contact with the people living in the urban locations.

With the booming of the economy in the post-war period and especially in the 1960s, migrants from Zebediela arrived on the Rand in bigger numbers and took up employment in various factories, including Iscor in Pretoria and Vanderbijlpark, south of Johannesburg. Many were employed by the South African Railways and various other industries. While some of the factories, such as Iscor and Eskom, kept their workers in their own compounds, many other employers provided no residential facilities and so the bulk of migrants sought accommodation in municipal hostels that sprouted ferociously across the length and breadth of the Rand in the 1960s. For instance, there were municipal hostels in Atteridgeville and Mamelodi in Pretoria, as well as in Tembisa, Springs, Daveyton, Katlehong, Thokoza and other townships on the East Rand, in addition to the hostels of Jeppe, Denver and George Koch in central Johannesburg and many more in Soweto and the Vaal Triangle.

Before the 1960s, the vast majority of Zebediela migrants arriving on the Reef were young men; a growing number of women were pulled into seasonal labour on neighbouring white farms where wages were quite low. Generally, chiefs and elders in the community vehemently opposed female migrancy, as was the case in Sekhukhuneland.8 From the 1960s onwards, however, more women were engaging in migrancy to the Rand, as a result of increasing landlessness and dependence on migrants’ remittances, combined with a growing demand for female domestic workers in white suburbs.

In the earlier decades, domestic work had been largely a male prerogative. Male migrants with some level of primary schooling were drawn into the kitchens and the hotel industry, as well as into hospitals as medical orderlies (male nurses).9 Soon after graduating from initiation school (koma) and upon completing his primary schooling (Standard 5 then or Grade 7 today) in 1942, Maesela William Aphane joined the flood of migrants to the Rand. He was assisted in finding a job by a male relative who worked in the kitchens in Pretoria. He was employed as a ‘scullery boy’ at the Carlton Bar and Restaurant where he was soon promoted to stock-keeper. Aphane then bought a camera and made a living out of taking photographs of people, an undertaking that facilitated his meeting and socialising with more migrants in white suburbs and also with location residents. At the height of this enterprise, Aphane employed three assistants and resided in Lady Selborne, one of the early black locations in Pretoria, from which the residents were forcefully removed and relocated to the township of Mamelodi in the 1960s. It was in this township that Aphane and his family were allocated their own house by the municipality.

Although he continued to be culturally and politically rooted in the countryside, Aphane became very cosmopolitan in his outlook and associated with individuals and groups from other regions.10 While a number of Zebediela migrants may have followed a similar life trajectory, the vast majority of migrants were much more deeply rooted in the countryside. Living in their employers’ compounds with and among their homeboys ensured that they were insulated from blending with and being influenced by people from the locations.

For an average migrant from Zebediela, town life was harsh, alienating and foreign, something to be kept at arm’s length, rather than to be desired. Many had come to terms with the necessity of embarking on spells of migrancy, not only for earning money to meet their tax obligations, but also for accumulating capital required for bride-wealth, the construction of a homestead and accumulation of cattle, which in the long run would allow for retirement in the village.11 As Peter Delius further elaborates in his study of the neighbouring Pedi:

Towns were regarded and described as makgoweng (the place of the whites) or lešokeng (a wilderness). Part of what defined them as such was the absence of core institutions like initiation and chieftainship and what many migrants saw as the corrosion of appropriate relationships of gender and generation amongst urban Africans … Most migrants saw the chiefs … as key symbols and guarantors of a rurally centred moral order.12

These feelings were shared by migrants from Zebediela. While in towns, these men lived harsh, grim and lonely lives, working in mines and factories controlled by the white people. Most lived in single-sex male hostels and compounds surrounded by strangers, some of whom spoke languages they did not understand. There were constant conflicts and competition over limited resources and jobs. As a result, migrants in such unfamiliar social environments tended to pull closer towards people who came from their home areas and/ or who spoke a common language. Such alien and competitive social environments gave rise to group consciousness and the articulation of ethnic identities.

It is important to note that such social divisions among the workers were patently beneficial to some industries and were thus often abetted by the employers to thwart the development of working-class consciousness and militant trade unionism. However, the development of collective identities was enormously psychologically comforting for migrants in that it helped to mitigate isolation and unfriendly, sometimes violent, encounters with authorities and migrants from other regions. Like others, the migrants from Zebediela became more reliant on their village or homeboy networks to get jobs in urban areas. In many instances, a great measure of solidarity developed between them, which served as a crucial building block in the formation of migrant organisations.

An interesting development among Zebediela migrants was the formation of burial societies. These acted as forms of self-help associations or funeral insurances. Members met once a month and made financial contributions that were pooled together into a bank account. In the event of a member’s death, a set amount of money was withdrawn and used to cover the transportation costs for the deceased’s body to be returned and buried in his home village. In this world of violence and disease, most migrants recoiled from the thought of dying at makgoweng and their mortal remains being buried among strangers, so far from home. Most wished to be buried alongside their ancestors back in the countryside. Burial societies, it should be emphasised, were important not only to migrants, but also to urbanised Africans.

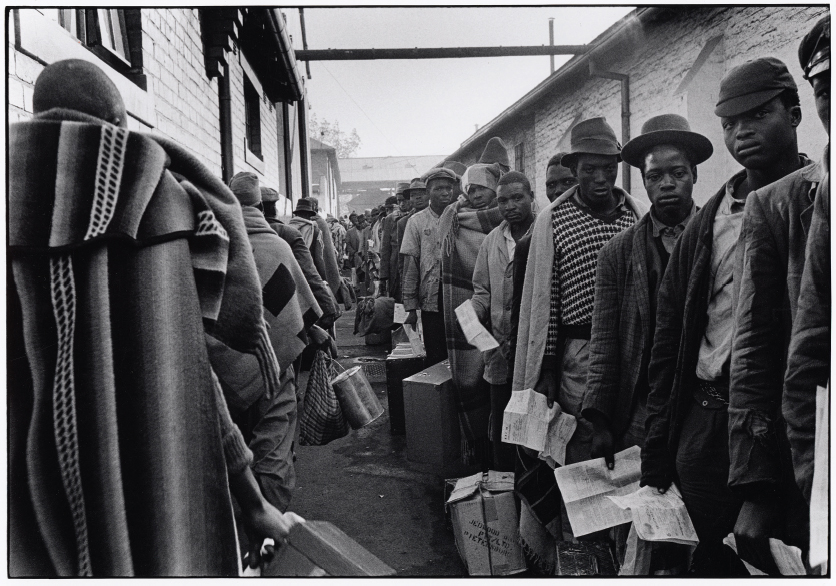

Figure 11.1

Ernest Cole

Contract-expired miners are on the right carrying their discharge papers and wearing ‘European’ clothes while new recruits, many in tribal blankets, are on the left (information supplied by Struan Robertson).

Date unrecorded

Ernest Cole Family Trust, courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation

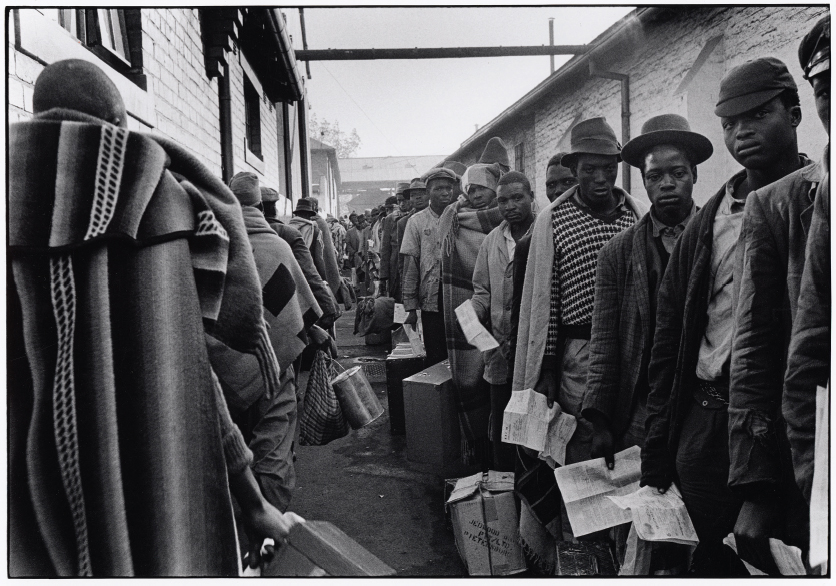

Figure 11.2

African migrant men dominated the domestic service sector in white suburbia until they were displaced by women who, because of the harsh economic realities in the countryside, took to migrant labour in larger numbers from the 1950s onwards.

Leon Levson

Domestic workers in kitchen

1949

Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg

Besides providing financial support in times of bereavement, migrants’ burial societies facilitated the formation of wider solidarities between migrants working in different sectors. Those working in the kitchens – and an increasing number of women from Zebediela were absorbed into white suburbia as domestic workers on the Rand from the 1960s onwards – were also drawn into these burial societies. In some cases, burial societies helped to bridge the deep-seated rifts between majakane (Christians) and traditionalists from the same villages by signing up migrants from both camps in urban areas.13 Yet, some Christian migrants remained aloof and would not join the societies that had baheteni (‘heathens’ or non-Christians) as members.

One of the burial societies that drew support from both groups was the Sebetiela Combined Society. Founded in Pretoria under the leadership of Ntilaka Joel Kekana around 1954, the society first operated in Beatrix Street before moving to Marabastad. After accumulating a fair amount of savings, Kekana persuaded the members of the society to purchase a lorry to be used as a means of transport for members when travelling to funerals in the countryside. Before long the society was embroiled in acrimonious wrangling and Kekana was accused of hiring out the lorry for personal gain.14

The most successful Pretoria-based migrant burial society, however, was the Mandebele Burial Society, which was based at the Iscor compound in Pretoria West. As mentioned earlier, Iscor was one of the factories on the Rand with the largest concentration of migrants from Zebediela. It is not surprising that a burial society specifically for the Ndebele migrants from Zebediela was constituted around that factory; it is most likely that other societies were formed that catered for other ethnicities. As archival records show, hundreds of Bakgatla-ba-Mochudi (from Bechuanaland Protectorate) arrived on the Rand in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and many belonged to their own burial societies (as well as to ethnic associations), one of which was based in Johannesburg.15 But, to return to Zebediela migrants, many of those that worked in Pretoria and the surrounding areas joined the Mandebele Burial Society and attended monthly meetings at the Iscor compound. The main thrust of these gatherings was certainly to ensure that members paid their monthly dues, but they also created space for migrants to discuss politics and debate new developments back home.

For most migrants from Zebediela, one of the most deeply perturbing developments in the 1930s and 1940s was the growing intervention of the state in rural African communities, especially in matters concerning land use and chieftainship. The problem started after the passing of the Native Trust and Land Act of 1936. Its mission was to ease congestion in reserve areas by weaning Africans away from ‘primitive’, ‘irrational’ and ‘wasteful’ ways of farming by teaching them scientific methods. Encompassing all existing rural locations and reserves in the South African Native Trust (SANT), the new Act expanded a layer of white officials at local levels to supervise implementation of new measures, such as the fencing of lands, the reduction of stock, as well as the establishment of dipping tanks and concentrated grid-planned settlements. Chiefs were to be the main fulcrum in the enforcement of these measures, with white bureaucrats acting as overseers.16 Officially known as the ‘Betterment and Rehabilitation Scheme’, but popularly called ‘Trust’ or ‘TC’, these measures were reviled by rural Africans across the country. This was also the case in Zebediela, where the Rand-based migrants would come to play a key part in opposing its implementation.

But why did migrants play a central role in coordinating resistance against Betterment measures? The answer to this question lies squarely in the migrants’ sense of their own identity and the changing world that they inhabited. Most migrants were rural people at heart. As we saw earlier, most men still considered migrancy as a means of sustaining a primarily rural way of life. While it enabled them to pay their taxes, migrancy also provided an opportunity for these men to accumulate the resources to marry, build homes and herds of cattle and ultimately to retire to their rural villages, away from white society and foreign laws.17 Within this context, the enforcement of stock reduction, the relocation of communities into grid-planned villages, the fencing of lands and the close supervision of farming practices represented a serious threat to the migrants’ future livelihoods. John Leshaba, a Pretoria-based migrant from Zebediela, recalls how, once Betterment measures began to be enforced:

People were forced to sell their goats for a mere one shilling each. This TC was unpopular … It led to the demarcation of arable land, cutting down people’s fields into small portions. My father’s field was so big that one would even be afraid that a wild animal might come out of it. There was even a small pond in it. He lost that land because of TC.18

Given such effects, it is not surprising that migrants participated actively in trying to keep Betterment at bay.

Matters came to a head on 27 April 1937 when the Native Commissioner, in consultation with the chief’s council (bakgomana), installed Patrick Ntedi Kekana as acting chief in the place of the heir, who was declared unfit to rule.19 A man with a strong personality and authority, on the one hand, Kekana was commended by the white officials from the Department of Native Affairs for being co-operative and meticulous in his enforcement of the Betterment Scheme. On the other hand, he was detested by many villagers who had to contend with the effects of the government measures he was enforcing. His fate was sealed when he grew arrogant and became ‘unruly’ in front of white officials. The Native Commissioner was only too happy to relieve him of his position in 1946, after receiving representations from the community via the bakgomana concerning Kekana’s reckless behaviour and negligence of chiefly duties.20 Therefore, when he was brought back ten years later (in 1956), ostensibly to act on behalf of his young nephew and heir, but in reality to take over from where he had left off in terms of implementing government policies – this time the introduction of tribal authorities – some villagers and, most importantly, a section of Rand-based migrants were outraged.21

Petrified by these developments, the migrants, together with a section of the bakgomana and the public at large, formed a more radical organisation, the Mandebele Cradle Association, in 1957.22 Popularly known as Pitšo ya Sekgweng, the organisation’s primary objectives were to resist Betterment and the state’s interference in the Kekana chieftainship.23 The mission was to remove Patrick so that the young Johannes Shikoane Kekana (who had attained majority by this time) could take over as chief. Under the rule of the young chief, these migrants believed that they would be more effective in resisting the government’s Betterment measures, which they saw as a danger to their rural communities. They were confident that they would be able to influence Shikoane to be more accountable to the people over whom he presided, rather than to the state, which would help give meaning to migrants’ sense of ethnic belonging.

The literal meaning of Pitšo ya Sekgweng is ‘a public assembly in the bush’. The name reflects the clandestine manner in which the organisation had to operate, in areas beyond the gaze of the state. Virtually all its rural meetings took place in the bush, far from the chief’s court (mošate), the rightful place for a public gathering (pitšo). In the event of public gatherings at home, the migrants hired buses and usually arrived at night to avoid detection.24 They also employed a well-known, Johannesburg-based lawyer, Attorney Godfrey M Pitje, in their endeavour to have the heir installed as chief.25 After a long and tedious struggle, spanning several years of litigation, public gatherings and the arrest and imprisonment of some of its leading members, the migrants’ association finally prevailed and Johannes Shikoane Kekana was installed as Chief Shikoane II in 1965.26 The latter was to become a key figure in the spirited Ndebele ethnic nationalist struggle, starting in the mid-1960s.

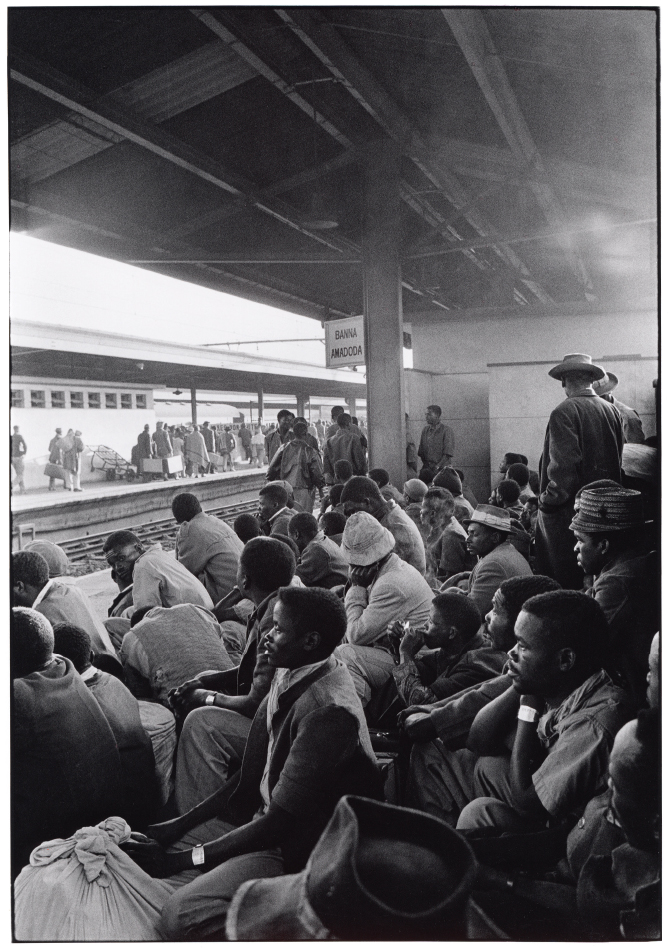

Figure 11.3

Ernest Cole

After processing, men wait at railroad station for transportation to mines. Identity tag on wrist shows shipment of labour to which men are assigned

1967

Ernest Cole Family Trust, courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation

Migrants, homelands and the crystallisation of Ndebele ethnicity, 1960s–1970s

In the meantime, the beginning of the 1960s marked a turning point in the way that many black South Africans, including migrants, perceived their identities; this was true as well for migrants from Zebediela. By this time, the liberation movement had been completely suppressed and forced into exile and there was political quiescence in the country. The National Party government commenced with the homeland system, using ethnicity as one of the main principles of separate development. Identification with homeland identities was a basic requirement for Africans, both in urban and rural areas, to have access to jobs, housing, trading licences, land and so forth. This process started with the establishment of the Xhosa homeland of the Transkei in the Eastern Cape in 1966 and other ethnicities got their turn shortly thereafter.27 Indeed, ethnic consciousness became more strongly articulated among migrants in urban areas, where inter-ethnic competition over scarce resources was rife. Within this context of homeland politics, it was inevitable that there would be a significant shift from earlier migrants’ collective identities, based on kinship ties and loyalties to particular chieftaincies, towards new and broader solidarities, based on allegiance to the ethnic group as a whole. It was no longer sufficient for Zebediela migrants, for instance, to rely only on bonds of kinship and homeboy networks to maximise their chances of accessing the limited resources.It is interesting that when it came to the Ndebele, initially no consideration was given to setting territory aside for the creation of an Ndebele ethnic enclave. Instead, the Department of Bantu Administration and Development (BAD) inserted the disparate Ndebele communities under the authority of Lebowa and Bophuthatswana.28 Initially, many Ndebele migrants were unreceptive to this approach, but after a bit of coaxing, they cautiously welcomed it, though some Ndebele nationalists, most of whom were migrants on the Rand, still had some reservations.29

It did not take long before fears of being dominated by the Pedi and Tswana surged among the Ndebele on the Rand. These fears were reinforced by subjective feelings of marginalisation. Tensions started flaring in the first joint meetings of the Ndebele and Pedi migrants in Mamelodi and Mofolo (Soweto) in the early 1960s to discuss the formation of the Lebowa territorial authority. These meetings were presided over by a Pedi chairperson, who insisted that speakers should use the official language, namely Sepedi. IsiNdebele had not yet been developed as a written language and was thus not officially recognised. All attempts by the Ndebele speakers to contribute to the debates in their mother tongue were blocked by the chairperson. This became a thorny issue, particularly for the Southern Ndebele, many of whom could not speak Sepedi, but even the Northern Ndebele delegates were equally distressed by this apparent manifestation of Pedi chauvinism. Things had now reached a boiling point; the Ndebele walked out of the meeting en masse, wondering how they could be expected to feel a sense of belonging in a homeland where they would not even have a right to speak their own language.30 The situation was no different in Bophuthatswana, as I show in other studies.31 So, the Ndebele migrants started establishing their own much broader ethnic associations in order to unite all Ndebele groups in South Africa and to fight for their own separate homeland.

Figure 11.4

While these men are in a rural setting, their style of dress shows that they are most likely to be migrants. The background mural designs are not as distinctively Southern Ndebele as they would become in the 1960s and 1970s.

Constance Stuart Larrabee

Ndebele migrant men in urban attire

1936–1949

Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art Collection, Washington, DC

In 1965, an organisation called the Ndebele Ethnic Group was formed in Mamelodi and Atteridgeville, with Koos Mthimunye as its chairperson.32 This body was established in response to the lack of Ndebele language programmes on the recently introduced black radio station called Radio Bantu (established in 1960), which provided services in most other African languages in South Africa. Initially very limited in scope, the organisation soon found itself agitating for official recognition of the Northern and Southern Ndebele as a united group. In 1967, a Soweto resident, Isaac J Mahlangu, formed the Ndebele National Organisation to promote the idea of a ‘separate Ndebele nation’.33 On 5 November 1967, members of different Ndebele bodies came together in Mamelodi and constituted a larger, more ambitious umbrella organisation called the Transvaal Ndebele National Organisation (TNNO).34 The main objective of this body was to fight for official recognition of all Ndebele groups – Northern and Southern sections together – as part of one distinct ethnic group that deserved a homeland of its own.35

By the late 1960s and 1970s, even the migrants from Zebediela had fully embraced Ndebele ethnicity and were counted amongst the most devoted supporters of the ethnic nationalist movement. In this politically charged environment, ethnicity had come to trump all other forms of identification. The government only started warming up to the idea of establishing a homeland for the Southern Ndebele around 1972, leaving the Northern Ndebele in Lebowa and Bophuthatswana. By this time, it was impelled more by the imperative to relocate and resettle surplus black labour from towns and white farms than by a commitment to separate ethnicities.

Conclusion

Since the late nineteenth century, the area of Zebediela has been a source of migrant labour on the Rand. In the early years, these migrants had more leverage in demanding higher wages. Access to land for growing crops and keeping livestock enabled them to withdraw their labour if conditions were not favourable. However, a combination of land dispossession and growing landlessness undermined their bargaining power and many families were dependent on migrants’ remittances by the 1930s and 1940s, thus propelling more and more men to spend long periods of time away from home. Even as they lived in towns for many months – sometimes more than a year – at a time, these migrant workers remained strongly attached to their rural homes. They used migrancy to accumulate the resources that they needed to be able to retire to their rural homes. In this context, migrants from Zebediela did not simply fold their arms, but responded by forming migrant associations when the state started imposing Betterment Schemes, which sought to restructure rural communities in ways that threatened migrants’ sense of manhood and identity.

Towns were harsh, hostile and alienating environments and so the Zebediela migrants, like their counterparts elsewhere, tended to identify with other migrants from their home regions. Such homeboy networks proved useful in helping to find accommodation and employment for newcomers from home, who arrived on the Rand in larger numbers from the 1940s onwards. In addition, these migrants established self-help bodies, such as burial societies, to ensure that in the event of death, their mortal remains would be transported back home and buried among their people. These organisations, of course, had their own internal dynamics and ways of including and excluding people, depending, for example, on whether the individual was Christian or non-Christian.

By the 1960s, ethnicity had become a key principle used by the apartheid state to determine access to scarce economic, social and political resources. As such, Africans (including migrants) became ethnicised; they accepted identities for purposes of gaining access to scarce resources. Unlike the earlier period when they depended on kinship and village networks to gain access to employment and accommodation in urban areas, this time much broader solidarities were formed, based on ethnicity. As we saw earlier, many migrants from Zebediela based on the Reef were drawn into wider ethnic associations that brought together the Ndebele from various regions in the country – regardless of their differences in cultural practices and dialects – to agitate for their own distinct homeland. These migrants were united not only by fear for the progressive disintegration of the Ndebele language and culture in the Sotho/ Sepedi- and Tswana-speaking homelands, but also by fear of economic and political marginalisation.

In the end, the development of ethnicity in South Africa cannot be explained simply in terms of the state’s or capital’s manipulation of identities. Situating the explanation of ethnicity at the level of the state tends to ignore the people who have developed ethnic consciousness and the historical processes giving rise to an expression of this phenomenon.36 This chapter has shown how individuals and groups from Ndebele communities, particularly migrants, took a lead in contesting and renegotiating among themselves as well as with the state, expounding and redefining their identities in the period before and during apartheid. During the latter period, the state provided strong parameters, within which ethnicity generally has taken shape. It manipulated those identities for its own purposes and, in the context of rigidly defined ethnic homelands, poverty, land shortage and vastly inadequate resources, it distorted and froze those identities to the point that, to this day, ‘ethnic’ divisions have continued to be a source of conflict in South Africa.

Notes

1. The Ndebele-speaking groups in South Africa have been classified into the Northern Ndebele and the Southern Ndebele. The former includes groups such as the Kekana of Moletlane, Mokopane and Hammanskraal, the Ledwaba of Mashashane, Nkidikitlane and Kalkspruit, as well as the Langa of Bakenberg and Mapela. The Southern Ndebele category encapsulates the different Nzunza chiefdoms, Litho, Pungutsha and Manala chiefdoms.

2. Zebediela stems from a Dutch corruption of the name given to Mamokebe, a Kekana-Ndebele chief, who earned himself the name Sebitiela (meaning ‘the one who pacifies’) among his people because of his diplomatic skills in the mid-nineteenth-century Northern Transvaal. In his encounters with the Boer authorities, Chief Sebitiela had opted to be co-operative in his relations with the new rulers. In the Sekhukhuni War of 1852 waged by the ZAR against the Pedi, he supplied a contingent of 400 auxiliaries, besides delivering supplies of maize and cattle. In return for this show of loyalty, Sebitiela’s people were exempt from taxation for a while and in 1885, a sizable location was beaconed off by the ZAR for them. University of the Witwatersrand (hereafter Wits), Historical Papers Inventory A1724, Zebediela Citrus Estate Records, 1862– 1974. See also South African National Archives (SANA) 7915, 70/337, ‘A Short History of the Zebediela Location and the Gompies Irrigation Scheme’, by the Chief Native Commissioner, 16 June 1938.

3. Wits Historical Papers Inventory A1724, Zebediela Citrus Estate Records, 1862–1974.

4. It was only in 2003 that the Zebediela Citrus Estate was returned to the Bjatladi community, the descendants of the original owners of the land, who were forcibly evicted from the 2 000 hectares of land in 1918.

5. Cited in Wits, Historical Papers Inventory, A1724, Zebediela Citrus Estate Records, 1862–1974.

6. Ibid.

7. P Delius, A Lion Amongst the Cattle: Reconstruction and Resistance in the Northern Transvaal (Johannesburg: Ravan Press; Portsmouth: Heinemann; Oxford: James Currey, 1996), 21.

8. Ibid., 22.

9. Alpheus Lesiba Ntlhane was one such medical orderly. After passing Form 3 (today’s Grade 10) in 1958, Ntlhane worked at the Penge Asbestos Mines for nine months before taking off to West Driefontein Mine No 2, where he worked as a checker of workers coming from underground. He then applied to become a trainee medical orderly at Lesley Memorial Hospital in 1962; thereafter to Philadelphia Hospital in Moutse; then to Carletonville, Nylstroom and Edenvale hospitals and finally he left for the factories and took up residence at Alexandra Hostel. Interview with Alpheus Lesiba Ntlhane, Ga-Rakgoatha, Zebediela, 16 April 2001.

10. Interview with Maesela William Aphane, Mamelodi Township, Pretoria, 30 May 2001 and 19 March 2005.

11. Delius, Lion, 23.

12. Ibid.

13. Interview, Maesela William Aphane, 19 March 2005.

14. Ibid.

15. Schapera Papers, 2/61, London School of Economics, I Schapera, ‘The Native as Letter-Writer’.

16. For a detailed discussion of the 1936 Native Trust and Land Act, how it came about and how the people of Sekhukhuneland contended with this piece of law, see Delius, Lion, 51–75.

17. Delius, Lion, 23.

18. Interview with John Leshaba, Mamelodi Township, Pretoria, 5 March 2005.

19. SANA, 27/55 2/1/2/1, ‘Re: Death of Chief Sello Kekana: Zebediela Location, District Potgietersrust’, Additional Native Commissioner to Secretary for Native Affairs, Memorandum, 03 June 1942.

20. Ibid.; interview with George Maboni Kekana, Makweng Village, Zebediela, 15 April 2001.

21. Interview, George Maboni Kekana.

22. Similar associations were formed in other communities. See, for example, PN Delius, ‘Sebatakgomo: Migrant Organisation and the Sekhukhuneland Revolt’, Journal of Southern African Studies 15.4 (1989), 581–615.

23. Interview, Ntlhane.

24. Interview, Leshaba; interview, Ntlhane; interview, Maesela William Aphane, 19 March 2005.

25. SANA, 27/55 N4/3/4/4; SANA, 72/55 Letter from Attorney GM Pitje to Bantu Affairs Commissioner in Potgietersrus, 27 March 1961.

26. SANA, 27/55 N1/1/3/1.

27. While some had doubts, many Africans accepted the homeland system and the politically savvy ones even hoped to use the spaces provided by these dummy structures to subvert apartheid from within.

28. The decision was based initially upon the demographic factor, a critical ethnological finding that the Ndebele were a tiny group, insufficiently culturally cohesive and thus undeserving of homeland status. Die Volksblad, 16 March 1979; C McCaul, Satellite in Revolt, Kwa-Ndebele: An Economic and Political Profile (Johannesburg: SAIRR, 1987).

29. CJ Coetzee, ‘Die Strewe tot Etniese Konsolidasie en Nasionale Selfverwesenliking by die Ndebele van Transvaal’, PhD dissertation, Potchefstroom University, Potchefstroom, 1980, 388.

30. Interview with Maesela William Aphane, Mamelodi Township, Pretoria, 30 May 2001; interview with Bennett Kekana, Soshanguve Township, Pretoria, 9 March 2001.

31. SP Lekgoathi, ‘Chiefs, Migrants and North Ndebele Ethnicity in the Context of Surrounding Homeland Politics, 1965–1978’, African Studies 1.62 (2003), 53–77; SP Lekgoathi, ‘Ethnicity and Identity: Struggle and Contestation in the Making of the Northern Transvaal Ndebele, c.1860–2005’, PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 2006.

32. Coetzee, ‘Strewe’.

33. Ibid.

34. Interview, George Maboni Kekana.

35. Coetzee, ‘Strewe’.

36. This long-established argument is made in L Vail (ed.), The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa (London: James Currey; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).