Some time in 2006, I met a retired gold miner who called himself Bungityala in his home village on the coastline of eastern Mpondoland. Bungityala’s village is among the most stunning places I have ever seen. The hills that surround it somehow manage to seem gently pastoral and yet exhilaratingly wild, for sometimes it is as if the wind is sweeping through you and lifting you off the ground and you are about to fly. In part it is because the topography is so unpredictable; you can turn a corner and suddenly find yourself staring way down at hilltops and you wonder how it is that you got so high. In the early evenings, I would sit in the spaza shops and the shebeens in little hillside sheds, drinking stout beer with the elderly people of Bungityala’s village. I can vouch that these elderly people are capable of drinking a lot of stout beer. They grow drunken and coarse and all sorts of venom and humour and amusement come tumbling from them and you can learn a great deal about a place by insinuating yourself into these snug sheds of inebriation.

Sitting in one of these sheds in the early evening, drinking stout beer with two elderly women, I looked out of the shed’s open door and I saw the legs and the torso of a great, athletic horse pass right by, just inches from the door. I stepped outside the shed to find an elderly man in sharp riding boots atop a magnificent racing horse. He looked down at me imperiously and smiled to himself, his eyes quite bloodshot, which struck me as odd, because he had not even sat down to his beer. I was to discover later that Bungityala had spent the entire afternoon taking his horse from one shebeen to another, that he already had a great deal of stout beer in his veins and this was his last stop on his way home, which was across the beach and on the other side of the lagoon.

Bungityala tethered his horse and entered the shed in his heavy riding boots and ordered a stout beer. He was a short man and his riding boots came almost up to his knees, which made him look even shorter, for it was hard not to imagine that the man only began where the boots ended. He sat down on a bench and immediately began staring at me – a white person and thus an unusual sight; he paid no more than cursory attention to the two women with whom I sat. He ogled me with his bloodshot eyes for a long time before finally shouting out a question. ‘Are you married?’ he asked. I replied that I was not and asked him his marital status, in turn. Bungityala said that in the course of his life he had had two wives. The first had been no good and so he had sent her back to her village and married a second.

I was sharing a bench with the two elderly women. Bungityala was on his own bench at the other end of the room. One of the old women lifted her chin in a grandiloquent manner and asked Bungtiyala very loudly if he got rid of his first wife because she could not bear children. The other woman bowed her head and sniggered into her tin cup of stout beer. Bungityala replied in a loud, proud voice. ‘On the contrary,’ he said, ‘I got rid of her because she had everyone’s children.’ He was clearly addressing me, and me alone, for I was, I am sure, the only person in the room who knew nothing of his past. ‘For nearly 30 years,’ he said, ‘I worked for nine months every year underground, in the gold mines, and on four occasions I returned home to find that my wife was pregnant. The fourth time this happened, it was enough. I could not stand the thought of seeing everybody else’s children running around wherever I went. After many, many years of marriage, I took my wife back to her village and told her to stay there and not come back.’

‘What happened to the lobolo?’ the woman who had lobbed the first question asked. And the other woman sniggered into her beer once more. ‘I demanded my cattle back,’ Bungityala replied. ‘I did not buy the woman’s soul. I did not buy her companionship. I did not buy her spirit. What I bought was her capacity to have my children and she kept having other men’s children. When I delivered my wife to her family, I said that when I go home from here, it will be with my cattle.’

The two women laughed into their beers and Bungityala fell silent. He remained silent for a long time, his head bowed. People came and laughed and chatted and Bungityala remained uninvolved. As the room grew gloomier and he still did not speak, I thought that I felt Bungityala’s sadness. He had arrived so buoyant at the end of what had clearly been a happily drunken afternoon. And these two women, whom he would not have encountered had he skipped this shed and gone home, had also spent the afternoon growing drunk and had become nasty in their drunkenness. They had given voice to a thought that must pass through the vast busyness of everyone’s mind whenever they cross paths with Bungityala: there goes that famous cuckold whose wife was unfaithful each and every year he was away at the mines.

Figure 15.1

Julius Mfethe

The Horseman

c1999

Wood, metal, leather, string Collection of Jack Ginsberg

Bungityala finished his stout beer and greeted me and the two women and walked out the door. Feeling that I had not had enough of Bungityala, I followed. He mounted his great horse and led it on the footpath that wound up the hill. They were such an incongruous sight, this small old man atop a huge beast, the two of them on a narrow footpath clearly made for feet, not hooves. It was winding and steep and full of stones and rocks and ditches and the horse threaded its way very carefully, walking sideways at times, until it summited the hill and made its cautious way down the other side, towards the beach, which had become a striking colour in this endof-day light, a washed-over orange, like the afterlife of a colour that had just died.

The moment he had led his horse onto the sand, Bungityala pulled a crop from his bag and slapped his horse on its side. The creature burst into a gallop and Bungityala tucked his body into the slipstream and rider and horse streaked across the twilight, becoming smaller and smaller, the sounds of hooves disappearing into silence. I stared at them until they were a speck and it soon seemed that the speck was growing bigger, an illusion spun by this semi-darkness, I thought, until it became clear that they were in fact growing larger and the sound of hooves returned and there was Bungityala once more on his horse. What was left of the light caught the white of his teeth and I realised that he was smiling broadly, smiling, indeed, with his whole face. What had just happened seemed so clear. Bungityala had steered his horse onto the beach wounded and hollow and had resolved to gallop away his woes. He had in the end galloped miles beyond Bungityala the cuckold into an other-world of speed and wind and sea. When he reached the end of the beach, he knew for sure that he was not done with this other-world and so he turned his horse around and kept galloping.

My thoughts as I watched Bungityala and his horse in the dying light were shaped by other things I was doing at the time. I was writing about the murder of a farmer’s son by the tenants who lived on his farm. Compared to Bungityala galloping his horse on the beach, the world of the white farmer and his tenants seemed horribly hemmed in. The white man wanted names; he wanted the identity numbers of all residents on his farm; he wanted to know when your child was born and when your mother died; he wanted to count your cattle and the number of huts in your homestead, he wanted, he wanted. Imagine, I thought to myself, if a white person had stepped onto the beach that evening and hailed Bungityala and told him that he, the white person, was turning the beach into a game farm and Bungityala could no longer ride his horse there. He would have laughed at the white person because the very idea of it would have been utterly ridiculous; the beach was for Bungityala and his horse, not for white people making game farms.

It struck me that in the last hour or two, I had watched Bungityala being unmanned and then retrieving his manhood and the manner in which both had occurred belonged quintessentially to a migrant gold miner. Or, to put it another way, his unmanning and re-manning had followed the arc of the miner’s peculiar relation to white people. He had been serially cuckolded because his work for whites took him away from his family for most of the year and few human beings in their prime can confine their sex lives to a person who is seldom around.

He had re-manned himself through wind and through speed, on horseback, on a pristine beach and this, too, was very much a migrant’s re-manning. For here was Bungityala, one among millions of men who had left their countryside homes for many months of the year to travel down shafts into the earth to retrieve gold. He had done this in order to maintain a life where there was a beach on which he could gallop away from the world whenever the world was too painful to bear, a beach that was his own and not for white people, by virtue of communal land tenure. On the beach that evening, he had freed himself from being embarrassed and teased, freed himself momentarily from the pains of being a person in this world. But his freedom was also a black person’s freedom, carved out by a century of migrancy in a white-ruled land.

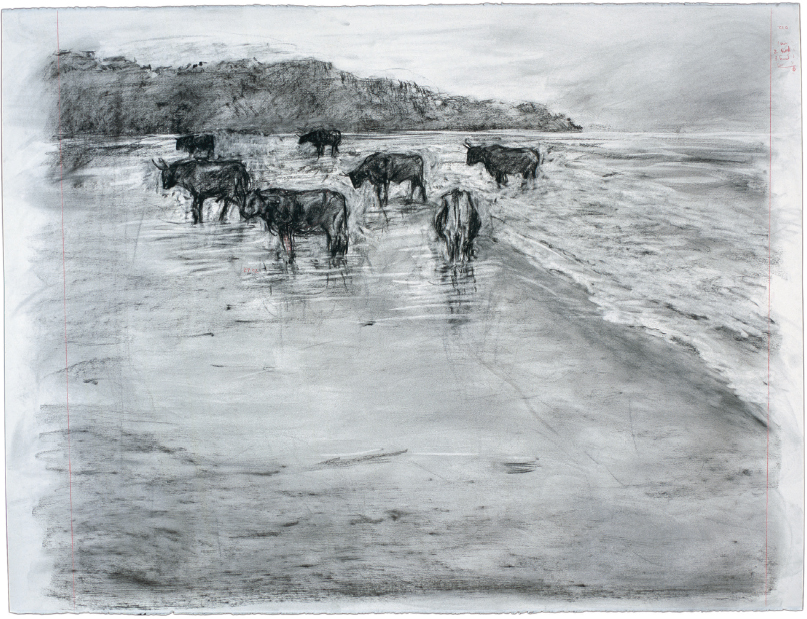

Figure 15.2

William Kentridge

Cows wandering on an Mpondoland beach

Still from animated film Tide Table

2003

35 mm animated film transferred to video, 8.50 min

Collection of the artist

I sought Bungityala out, for I wanted to talk to him at much greater length and he was not hard to find because, when he was not spending the afternoons drinking stout beer, he was spending the afternoons in the sun, leaning against the whitewashed wall of a village shop, smoking cannabis (dagga) in his pipe. And he was very happy to have a curious white man and his interpreter ask him a thousand questions about his life, for it was an opportunity to entertain.

I had noticed on that evening of his humiliation that Bungityala had only nine fingers. Now, in the sun, leaning against the whitewashed wall, I asked him how he had lost his finger and he told me a little about being a winch operator underground, how the wench has two handles that move in opposite directions and how his finger had been caught between them. But underground did not interest him very much. He wanted to talk instead about life on the surface.

‘Hostel life was wonderful,’ he said, apropos nothing. ‘Not like today. You spent nine months of the year in the hostel and you didn’t need to go out, you didn’t need to expose yourself to the danger of the township because you had everything you needed in the hostel. Today, they allow women into the hostels, even prostitutes. But then there were no women.’

By now, Bungityala had an audience. Aside from my interpreter and I, two other elderly men had joined us. One was sitting on an upturned barrel. The other had settled himself next to Bungityala and was sharing his pipe.

‘I arrived at the hostel for the first time with my cousin,’ Bungityala continued. ‘He had already been working on the mines for some time. I myself was a very young man. My cousin told me there were no women in the hostel. On my first day, I walked into the shower, saw a woman, turned around and ran away. My cousin laughed in my face. “You did not look closely enough,” he said. “That was no woman. That was an Mpondo man, but like no Mpondo man you would ever see in a village in the Pondoland.” ’

‘Just when I was recovering from this shock,’ Bungityala continued, ‘my cousin sent me to a shop to buy dagga. There was a beautiful woman behind the counter. She flirted with me as I was buying the dagga. She made sure that our hands touched as she passed me the matchbox of dagga. I went back to my cousin babbling about this beautiful woman. My cousin said, “Are you sure it’s a woman?” ’

His audience was laughing appreciatively now, but as quick as a flash, Bungityala became angry. ‘It was mining management who forced these men to become women,’ he said, ‘so that the miners wouldn’t have to go into the township. It was mining management who forced Mpondo men to become something they were not. The hostels were terrible places. Terrible things happened there.’

His elderly companions still chuckled, but now in a hesitant and uncomfortable way. It was fine when he drifted from memory into fantasy, for that was fun. But when he switched from lightness to anger, it was another story. One had to tread cautiously. One was no longer sure how best to respond to his tales.

My interpreter was a young man and a stranger from another district. Emboldened, perhaps, by the fact that our informant was as stoned as a kite and something of a clown, he tossed a naughty question into the conversation.

‘These men who became women,’ he asked, ‘did you greet any of them this morning on your way here?’

Bungityala eyed him suspiciously. ‘They are just ordinary men from the villages,’ he said. ‘You cannot tell from looking at them who they are.’

‘In your eyes, will they be women for the rest of their lives?’ my interpreter asked. ‘Or are they just normal, married men like you?’

I am certain that my interpreter knew the answer perefectly well. He was just taking advantage of Bungityala’s slide from dignity.

‘These men come back here and get married,’ Bungityala said. ‘Sometimes they even leave their wives behind, they are married when they go to the mines.’

‘So they are husbands here and wives there?’ my interpreter asked incredulously.

‘Yes.’

‘What is their motive for becoming wives?’

‘These boys make a lot of money,’ Bungityala said.

‘They can come back home and buy five cattle. You come back and you can only buy one and people ask you how you wasted all your money.’

‘Were you ever tempted to make money that way?’ my interpreter asked.

‘If you fail to do it the first time you come to the mines,’ Bungityala replied, ‘you can’t do it on your second visit.’

‘Why not?’‘It has to do with your courage to act. There is also a question of trust and mistrust. I can’t explain. You have to do it your first time.’

‘Do you know men in this village who were wives in the hostel?’ My interpreter asked again.

Now all three men were guffawing. ‘Yes,’ one of them replied on Bungityala’s behalf. ‘But I can’t name them. There are several here: there and there and there,’ he said, pointing his finger in many directions. ‘I will tell you a secret: whoever in this village owns many cattle was a wife on the mines.’

‘So,’ I suggested, infected by the success of my interpreter’s prurience, ‘those who have been to the mines know who in this village has been a wife, but it is a secret among you. You don’t tell other people.’

‘Actually,’ Bungityala replied, ‘everyone knows. It is just that you cannot say so in front of the ones who have been wives. Or they will hit you with a stick. There is a preacher, the one who lives up on that hill. He mentions it in his preaching. When he talks about things he did in his past, he raises this issue. He says this one did it and that one did it and they have cattle now because they abandoned God’s ways when they were starting out. There are men in this village who wish to beat that preacher with a stick.’

I thought often about Bungityala over the following months, but in an idle sort of way. He was an uncomfortable man, I thought, a man who was not at all sure of how best to go about the business of being a man. To the extent that his stoned and drunken bantering had revealed the world inside his head, it was a world where things did not stay stuck down where they belonged. Wives had affairs when their husbands went to the mines, turning them into less than proper men. And the men themselves sometimes became wives. Although they turned back into men at home, the residues of their wifeliness followed them wherever they went, rendering the world not quite right.

It is just as well, I found myself thinking, that Bungityala was a gold miner and not a labour tenant, for he was just the sort of man who might slaughter a white farmer’s son. So uncertain of himself, so quick to feel belittled, that hemmed-in feeling on white-owned land may well have driven him to murder. It is better that he is out here where there are no white people and there is the beach and his horse and the ocean air.

But the thought of Bungityala as a labour tenant immediately felt wrong, for everything about his uncertainty and his discomfort belonged to a migrant gold miner. When he looked out at the village onto the homesteads of men who had been women and when he peered inwards and examined his own cuckolded self, what he saw was neither pure village nor pure mine, but an amalgam. Each world had stained itself on the other. For years to come, people will sit against that whitewashed wall smoking dagga and looking out at their village, but they will not see what Bungityala sees, for his eyes take in a long history, the very mainstay, in fact, of twentieth-century South African history.

As I say, these were idle thoughts, but they were rudely sharpened one morning by a piece of news. I was in Johannesburg and was talking on the phone to a person from Bungityala’s village. Something was very wrong with Bungityala, my informant told me. Some months back, he had begun limping. It had got a little worse every day, until finally, and with much reluctance, Bungityala had agreed to be taken to hospital. He stayed there a long time, perhaps as long as six weeks and, when he returned, he was missing a foot. He tried hobbling around on crutches, but the footpaths of his village were not made for a person with one foot and, after a few days, Bungityala stopped leaving his home.

‘You know that he is a difficult man,’ my informant continued, ‘and has never got on well with his second wife, or with his children, for that matter. When he lost his foot, he became much more difficult. He would shout and he would be rude. And so now he is isolated. His family come at mealtimes to feed him. Every now and again, someone comes to help him wash. Once in a blue moon, his dagga-smoking friends bring him dagga. But, for the most part, he is alone.’

I was scheduled to visit Bungityala’s village in a couple of weeks. I thought of questions to ask him and bought a fresh set of clothes for him to wear. I made a mental note to bring him some beer. But when I arrived in the village, I was told that I had just missed him. He had been buried the previous day. I asked what had become of his horse. His creditors sold it a few weeks before he died, I was told. He owed money to four or five shebeens and spaza shops and when it became evident that he would never repay his debts, they banded together and sent a deputation to see him and when they left, they took his horse.

Bungityala’s death left me feeling empty and a little depressed. I could not shake the thought of him from my mind. I asked whether his family had been with him when he died and was told no, his son had found his corpse one morning. I asked, too, what had been the matter with his foot, but nobody seemed to know or to care much.

I visited the regional hospital where Bungityala had spent so much time and found his doctor. He was a lovely Congolese man, fat and garrulous, and he seemed genuinely saddened by the news that his patient had died. He frowned and stared at a point somewhere behind my shoulder, just momentarily, before making eye contact again.

‘I first examined the old man months ago,’ the doctor told me. ‘He had a terrible infection in his toe. I cleaned it and dressed it and put an antibiotic cream on it and gave him antibiotics to take orally, for it was clear that the infection was no longer just in his toe. But I could see from the look on his face that he would not take them. So I questioned him. At first he would not answer me nicely. So I took a stool and sat next to him, and my interpreter sat on the other side of him, and we laughed and made him comfortable. Eventually, he told us what he really thought. He said that his toe was broken, he knew the feeling of a broken bone. I told him it was not broken, it was riddled with bacteria. He said, no, it was broken and he would mend it the way he had been mending the broken bones of his cows for the last 45 years, by going to the forest and finding a plant that mended broken bones.’

The doctor opened his arms and shrugged his shoulders. ‘That was a stubborn old man,’ he said. ‘When I next saw him his foot was rotten. There was no saving it.’

I visited Bungityala’s grave, an unmarked mound on the edge of a small maize field just beyond the periphery of his homestead. I do not think that his family much enjoyed his memory; walking past his grave every day, I imagined, they would soon stop noticing that it was there.

It came to me with a shudder that on the two occasions I had met Bungityala, he had shown me the parts of him that would cause his death. Many people die because their relation to other people and to the world in general is not quite right. When Bungityala looked at himself, he saw an unhappy old cuckold and when he observed others, he saw them laughing at an old cuckold. When his foot began rotting, he crouched over it and protected it from the world, when he ought to have offered it to the world for healing.

I had come to Bungityala’s village to write about the AIDS medicine that had arrived in full force a year earlier. A new language was spilling off young people’s tongues. They were speaking of viral loads and CD4 counts. They were beginning to learn that a person was most infectious while still strong and healthy. They knew which antibiotics cured shingles and which fought respiratory infections. They knew that a thin, emaciated person who began drooling from the mouth and having visions had in all probability contracted cryptococcal meningitis and was in deep trouble.

Bungityala knew none of this. When I asked him about AIDS, he said that one might get it from sitting on the chair from which an infected person had just arisen or by wearing his jersey.

‘How do you know this?’ I asked.

‘I was listening to the radio,’ he replied. ‘They said there that if a person cleans his private parts with a towel and then you use his towel, you will get the virus. So why not also his chair and his jersey?’

New knowledge was coursing through the heads of so many of the people Bungityala passed each day. His own head was busy with other, more difficult thoughts, about the boundaries between men and women, for instance, and how they were not marked clearly enough. He had not coped very well with being both a migrant gold miner and a man and, as a result, he was locked inside a migrant’s dying world. Nothing new could seep in.

All around, fresh insights pulsed through the lives of others. People who might have died were alive. People who might have been sick in bed walked briskly over Bungityala’s grave. The world was renewed.