Benoni, Boksburg, Springs, Egoli, we make you rich.

We hostel people make you rich.

You send us back home to die with empty pockets, empty dreams and dust in our lungs, chopped-off hands and machines grinding in our brain.1

Trade unions have historically played a critical role in the struggle for emancipation in South Africa. Despite severe legal restrictions and repression, black workers formed unions to fight for better conditions in workplaces and, at key moments, also against the system of white minority rule. Often these unions were influenced by socialist ideas, causing them to be in the forefront of the struggle against capitalism. At different times in the twentieth century, black trade unions posed a serious challenge to dominant class relations at the point of production, which invariably affected the entire political establishment. Migrant workers featured prominently in these struggles.

These workers, who were overwhelmingly African men, have historically constituted the backbone of South Africa’s labour force. Predominantly concentrated in the mining sector from the late nineteenth century, migrants were also employed in increasing numbers in industry and municipalities as the secondary economy and urban areas expanded in the twentieth century. Their lives were ruled by a migrant labour system characterised by restrictive labour controls and relatively low wages, which entrapped them on the margins of society. As the modern economy expanded and concomitantly the demand for labour, the number of migrant men spending time in urban areas for extended periods also registered sharp increases. Most of them found life in the towns, which oscillated between low-paid toil in the mines or factories and the dreary (and increasingly derelict) hostels, deeply alienating. But, as Peter Delius has explained, migrants ‘did not allow themselves to be transformed into atomised economic units tossed to and fro in the swirling currents of market forces’.2 On the contrary, they constantly struggled against various aspects of their exploitation.

Migrant workers devised various responses to their circumstances in the urban economy, from mutual support to collective resistance. They created associations, invariably born from rural-based networks, which while providing support in the harsh urban environment and maintaining links to rural homes, also engendered solidarity in workplaces.3 The development of collective identities was also augmented by the propensity of migrants from particular rural areas to cluster in workplaces and hostels. Hostels symbolised capitalist development in South Africa and were designed to achieve two overarching objectives: to minimise capital’s labour costs and to maximise control and surveillance over black workers.4 Yet, these austere edifices were routinely reconfigured into contentious spaces as their inmates opposed the multiple infringements on their dignity. At the heart of these acts of resistance were the various migrant networks and associations, which effectively utilised the presence of large numbers of workers in hostels to mobilise collective struggles. Delius has explained how migrant networks from Sekhukhuneland, under the leadership of Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and African National Congress (ANC) activists, were instrumental in the establishment of a movement called Sebatakgomo, which not only played a leading role in the Sekhukhune rebellion of 1958, but also in the creation of nascent underground networks of Umkhonto we Sizwe in the early 1960s.5 What the experience of Sebatakgomo revealed quite dramatically was the political agency of migrant workers. Migrant workers’ militancy was primarily manifested in workplaces. Their active involvement in trade unions arguably represented high points of worker organisation and often resulted in significant changes in the relationship between capital and labour.

Migrants responded in multifarious ways to this system of pervasive oppression. Resistance – spontaneous and variously organised – featured perennially and tended to focus on wages, dismissals and the authoritarian and racist managerial control (baasskap). Desertion, go-slows, demonstrations, occupation of shafts and strikes constituted important elements in the repertoire of migrants’ resistance. During the course of these struggles different, albeit usually overlapping, organisations were mobilised and produced to engender solidarity in the face of customary inflexibility of the the mining companies and other employers. Trade unions were among the most important of these workplace organisations. Until the mid-1970s, trade unions only intermittently entered the lives of the majority of migrant workers, especially on the mines. However, when black trade unions did establish themselves and embarked on militant struggle, migrant workers were invariably central actors. This was evident in three important waves of black trade unionism: the period around the First World War, the 1940s and the period beginning in the early 1970s. Here the focus is mainly on the latter phase of independent black trade unionism, which culminated in the development of the most powerful union movement in South Africa’s history. This chapter highlights the pivotal role played by migrants in the birth of this movement and until the mid-1980s. Throughout this period, migrants’ struggles shaped the character of the new unions, largely determined the principal issues of contestation with employers and ultimately transformed the labour relations regime of the country. Workers’ struggles and black unions constituted one of the central pillars of the anti-apartheid struggle (another being community struggles). Support for radical ideas, workers’ unity, non-racialism and workers’ democracy were among the salient characteristics of this movement, all of which were profoundly present at the birth of democracy in South Africa.

Resurgent unionism

There were signs, in the late 1960s, of mounting worker discontent, especially against low pay. For example, 1 000 casual dockworkers at Durban’s port went on strike for higher wages in 1969. It was arguably the most important case of industrial action by African workers in the 1960s, but the dismissal of all the strikers demonstrated that the balance of power remained firmly on the side of employers. Although this action did not break the industrial quiescence of the 1960s, it was a harbinger of the challenges black workers would mount against the status quo in the early 1970s. The inaugural moment in the renaissance of workers’ struggles was undoubtedly the 1973 strike wave in Durban, which led to the transformation of South Africa’s industrial landscape and ultimately played a pivotal role in the demise of apartheid. Migrant workers were strongly present at the beginning of this movement and, over the next decade or so, were arguably the crucial constituency that shaped a new, militant unionism.

In January 1973, approximately 2 000 African workers at Coronation Brick and Tile Company went on strike to demand a minimum wage of R30 a week. High inflation and the failure of employers to pay wage increases to match the surge in the cost of living were the principal factors behind the demand for higher wages. Prices of crucial items, such as food, clothing and transport, increased by a staggering 40 per cent between 1958 and 1971 and then, even more sharply, by 30 per cent in the financial year 1972–1973.6 Significantly, the strike was mobilised at the company’s migrant hostel,7 thereby establishing a template for how migrant workers’ struggles would be mobilised and organised over the next two decades. Within days, workers at other companies in Durban also went on strike to demand wage increases. By the end of March, more than 160 strikes (involving approximately 60 000 workers) were recorded, easily eclipsing the number of strikes for the entire 1960s.8 The quiescence inaugurated by the repression of the early 1960s was shattered.

Striking workers did not win most of their demands, although in several cases employers were forced to concede unprecedented wage increases. However, the strike wave had two crucial and long-lasting consequences: it triggered a profound transformation in the attitude of African workers, who henceforth exhibited growing confidence to challenge white baasskap on the factory floor, and it heralded the start of the resurgence of black trade unionism in the country as a whole.9

Figure 16.1

Ernest Cole

Barrack-like buildings are divided into starkly simple rooms with bunk space for 20 men. There are no closets or cupboards so clothes and boots hang all over

1967

From House of Bondage, University of Cape Town Digital Archives

Ernest Cole Family Trust, courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation

Within months of the spontaneous outbreak of worker militancy, a number of new, independent black trade unions were launched.10 In April 1973, the Metal and Allied Workers’ Union (Mawu) was launched, with a membership of 200 based at two factories, making it the first of a new generation of non-racial unions.11 In September, the National Union of Textile Workers (NUTW), consisting mainly of women, was also launched and the following year, two new unions, the Chemical Workers’ Industrial Union (CWIU) and the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), were established. These four unions constituted the crucial foundation upon which the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu) was built and later were also instrumental in the establishment of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu).12

In Cape Town, the birth of new unionism differed markedly from the Natal experience. There the Western Province Workers’ Advice Bureau (WPWAB) was established in March 1973 to recruit workers into factory-based ‘works committees’ that would constitute the bases of a general workers’ union. The vast majority of the initial recruits were migrants from the Bantustans of Transkei and Ciskei. African workers in Cape Town experienced severe restrictions due to the coloured labour preference policies, which restricted them to unskilled jobs and onerous one-year contracts, causing endemic job insecurity.13 By the end of 1973, the WPWAB had 2 000 members in 14 works committees and by the following September, this figure had increased to 3 000 members in 24 works committees.14 Its success was probably built on two factors: the establishment of democratic structures that gave workers some authority over the running of the organisation and the recognition of the works committees, which allowed workers to negotiate directly with employers at the factory (albeit with the support of union activists).15 The latter especially provided African migrants with a degree of protection as they sought to improve their working conditions.

Over the next few years, the new union movement experienced mixed fortunes. Strikes continued, albeit on a smaller scale than in 1973, and union membership grew steadily, but modestly. By 1975, the membership of Mawu, NUTW, CWIU and TGWU in Durban had increased to 5 000, 7 000, 20 000 and 2 300 respectively. Mawu and CWIU had established a presence in the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vereeniging (PWV) region, the economic hub of the country. The PWV comprised three major urban and industrial conurbations and in the post-apartheid era has come to be known as the Gauteng province. At the same time and as a result especially of state repression and an employer backlash against the gains made during the strikes, the rate of growth of the new unions declined. But in the aftermath of the Soweto 1976 uprising, unions entered a period of consolidation and then, from about 1980, rapid expansion.

Militant migrants

A key moment in the development of independent unionism in the Cape and nationally was the Fatti’s and Moni’s struggle of 1979. African migrants were again centrally involved in a dispute that lasted seven months, was built on unity between coloured and African workers and eventually succeeded due to the mobilisation of community solidarity.16 In April 1979, scores of workers at the pasta and milling plant of Fatti’s and Moni’s went on strike against the company’s dismissal of workers who had drafted a petition calling for the recognition of the Food and Canning Workers’ Union (FCWU). Forty of the African workers on strike were migrants from the Ciskei, who were in danger of immediate deportation if their contracts were terminated. In fact, four of them were formally charged for being in Cape Town for longer than 72 hours.17 The success of the strike inspired similar boycott campaigns to support striking workers, such as in the red meat, Wilson Rowntree and Colgate disputes.

A new mood of defiance was taking root among black workers, not least because an increasing number realised that unions were absolutely crucial in their struggle to protect jobs and campaign for higher wages. This was especially pertinent in the context of rapidly deteriorating economic conditions, which caused high inflation and threats of widespread retrenchments. In the early 1980s, official inflation stood at 14.6 per cent, while the price of bread had rocketed by 30–40 per cent. On the East Rand, housing rents rose by 30 per cent and hostel accommodation by a staggering 70 per cent.18 Workers were being squeezed on all sides. As companies went on the offensive to protect profits, worker militancy increased. This was no more evident than among migrant workers on the Witwatersrand employed in metal and engineering firms in the early 1980s, who found every aspect of their lives – in urban and rural areas – under severe threat. These workers did not qualify for housing in townships and were forced to live in overcrowded and insalubrious compounds. In the factories, they were subject to white managerial control, characterised by abuse and the constant threat of dismissal. Loss of employment meant migrants would lose the ‘privilege’ of being in urban areas and thus be forced to return to the rural areas, which in the early 1980s experienced massive impoverishment caused by drought and overcrowding.

Conditions in rural areas, particularly the Bantustans, experienced a steady decline for a number of decades. Tightening of influx control and the promotion of Bantustans in the 1960s had several adverse consequences for rural livelihoods. Farming activity was confined to the Bantustans, while the population of these areas grew significantly. For example, the population of Sekhukhuneland rose sharply in the 1960s and nearly doubled between 1970 and 1980.19 As a result, subsistence farming faced mounting problems and food security was jeopardised. Droughts, disease and corrupt authorities added to the woes of rural communities. With conventional rural livelihood practices coming under severe pressure, reliance on wage remittances from migrant workers increased considerably from the 1970s. Defence of jobs in a context of severe economic crisis thus became a source of bitter class contestation. One explanation for the surge in migrant workers’ militancy in this period was the coalescence of serious challenges to migrants’ rural and urban livelihoods and way of life. The deterioration of conditions in the rural areas had a major impact on workers and their families’ lives, while the prospect of dismissals threatened the only available source of alternative income to sustain rural households. Militant unions therefore represented a first line of defence against the loss of work, but crucially against the prospect of an indigent life in a rural Bantustan.

According to Kally Forrest, ‘semi-skilled and unskilled migrant workers … became the backbone of MAWU’.20 This was especially true on the East Rand (Ekurhuleni), the heart of the country’s engineering industry. From the late 1970s, Mawu consciously sought to recruit these workers and, as Forrest explains, ‘won their trust by campaigning around migrant contracts and lack of work security’. In response to widespread retrenchments in the industry, the union launched a campaign to force employers to negotiate over retrenchments.21 Winning formal recognition created an important sense of security for workers who historically were at the mercy of managerial authoritarianism.

Under the leadership of Moses Mayekiso, who himself in the early 1970s had migrated from the Eastern Cape in search of work in Johannesburg, Mawu used the hostels as sites for the building of the union. Kathorus, the large African township complex near the major industrial areas of the near East Rand, had several hostels that housed thousands of male migrants. For example, 15 000 men lived in the Vosloorus hostel alone. Often denied access to the factories, union activists successfully organised in these spaces, spending considerable time with migrants, explaining union policies and strategising about how to campaign in factories. Regular mass meetings involving thousands of workers were held in the hostels, thus subverting their intended role as centres of control over the lives of migrants. The proximity of these hostels to urban townships facilitated contact between migrants and local workers, which contributed to the success of the township-based shop stewards’ councils that operated on the East Rand.

Victories scored by Mawu against dismissals and for higher than expected wage increases, in circumstances of worsening economic conditions, engendered a mood of defiance among workers on the East Rand. Hostel-dwellers from Kathorus and Tembisa were at the heart of a strike wave in 1981 that involved approximately 25 000 workers in 50 strikes. The two principal grievances undergirding these struggles were wages and arbitrary dismissals.22 Mawu’s success in recruiting migrant workers into its ranks contributed enormously to the unions reported growth in the Transvaal, from 6 000 in 1981 to 10 000 in 1982. According to Forrest, the strike wave on the East Rand was a primary reason behind the surge in the union’s membership from 10 000 in 1980 to 80 000 in 1983, which made it the ‘largest black union in the country’.23

Municipal workers’ strike

The contradictions and challenges faced by migrant workers in their efforts to unionise and to improve their status in urban areas were graphically revealed in the struggles by Johannesburg’s municipal workers in 1980. On 29 July 1980, 10 000 African municipal workers went on strike to demand higher wages in what Jeremy Keenan describes as ‘the largest strike ever faced by a single employer in the history of South Africa’.24 At the time, the majority of Johannesburg City Council’s (JCC) employees were migrants (12 000 out of 14 000) who, as contract labourers, were relegated to low-paid and unskilled jobs. Average earnings for these workers were between R31 and R33 per week (of which varying proportions were remitted to families in rural areas).25 Discontent over wages was widespread and deepened in the late 1970s as the JCC minimum wage fell behind the national average. By 1979, the average national wage was 25 per cent higher than the wages earned by African municipal workers.26

The immediate cause of the 1980 strike was the JCC management’s attempts to impose a sweetheart union, the Union of Johannesburg Municipality Workers (UJMW), on a workforce who had demonstrated a growing desire to establish a union that could fight for their rights. Workers rejected this ploy and walked out of the mass meeting convened to launch the union. A hastily organised committee of workers then proceeded to plan the formation of an independent union, which was officially launched in June 1980. About 300 workers attended the founding of the Black Municipal Workers’ Union (BMWU).27 Within a week, the new union was thrust into the middle of a dispute when workers threatened to strike over the small annual increment imposed by the JCC. The union undertook to negotiate on behalf of the workers, but the authorities refused to engage with an unregistered union. With the matter unresolved, workers at Orlando Power Station went on strike on 24 July and five days later they were joined by nearly 10 000 municipal workers across the city. Workers issued a number of basic demands: equal pay for equal work; a pay increase of R25 per week for unskilled workers and recognition of the BMWU. However, the BMWU was still in its infancy and quite weak. It claimed a membership of 9 000, but only had 900 signed-up members.28 As a result, it lagged behind events, trying to prevent an outright confrontation with the authorities.

Despite the union’s weakness, support for the strike spread rapidly because the grievances affected all African workers, while the intransigence of the management made workers more determined to forge ahead with strike action. Most importantly, workers used their existing networks in the workplace and in the hostels to mobilise for the strike. The vast majority of Johannesburg’s migrant employees lived in the 19 municipal compounds spread across the city. The Selby compound exemplified the extreme control exerted over the lives of migrants. Housing approximately 1 300 male migrants, it was

surrounded by a high wall topped with barbed wire. It has two entrances. One is through massive steel gates which are flanked by a permanent police guard post. The other entrance is a well-guarded and easily controlled subway … this makes it possible for the workers to be locked inside the compound.29

Yet, as labour researchers revealed, ‘compounds played a crucial role in both spreading news of the strike and in maintaining worker solidarity throughout its duration’.30 Throughout the strike, hundreds of workers congregated at the hostels and in one instance, a meeting of 3 000 to 4 000 workers was organised at Selby compound. In so doing, migrant workers employed by the largest city in the country demonstrated a willingness and capacity to organise strike action to improve their working conditions.

Faced by this unprecedented challenge to its authority, the JCC moved swiftly to crush the strike. The police invaded compounds and gave workers an ultimatum: return to work or face deportation. Approximately 1 000 migrants were in fact bussed under police escort to the Bantustans. Workers in the cleansing department were forced back to work at gunpoint, while leaders of the BMWU were arrested and charged with sabotage. State repression revealed the determination of the authorities to maintain control over the largely migrant workforce. While this historic strike was violently crushed, migrant workers had sent a powerful signal of their determination to fight against baasskap.

Miners to the fore

By far the largest concentration of migrant workers was to be found on the mines, for a long time the most important sector of the South African economy.31 From the late nineteenth century, thousands of young African men were recruited to the mines, many of them remaining there for their entire working lives. In 1920, there were 174 402 black migrants employed on the mines. At the time of the miners’ strike in 1946, this figure had increased to slightly more than 298 000 and in 1954, the 300 000 level was reached. Over the next three decades, mining employment grew steadily, reaching a high point of 477 398 in 1986.32 Migrants were drawn from the entire southern African region and for an extended period, until the late 1970s, constituted the majority of the workforce on the mines. African mineworkers faced a range of difficulties that placed them among the most exploited labour in the country. Wages were notoriously low: the average annual income of an African miner in 1945 was a mere £47 and by 1960, it had increased to £70. In stark contrast, white miners earned £646 and £1 136 respectively in these years, which meant that black workers earned between 13 and 16 per cent of the income of their white counterparts.33 Black wages remained seriously depressed until the early 1970s (the average monthly income was about R18) when the gold price began to rise sharply, which produced relatively significant wage increases. By 1986, the average income of black gold miners had risen to R425, but was still only a quarter of the average white wage.34

Furthermore, migrants on the mines were confined to compounds designed to impose strict control over the private, social and leisure time of migrants and to minimise contact with the surrounding urban world. In 1990, there were 140 mine compounds accommodating anything between 100 and 10 000 single male migrants each. Although living conditions had improved from what had prevailed in the early twentieth century, inmates continued to experience overcrowding, unhygienic kitchens and bathrooms and strict surveillance.35 African miners also experienced appalling safety conditions: during the course of the twentieth century, approximately 46 000 miners lost their lives underground and between 1983 and 1987 alone, a staggering 50 000 sustained permanent disabilities.36

Confronted with these multiple hardships, it was not surprising that African miners would engage in struggles to improve their lot. Protests assumed various forms, including strikes, desertion, go-slows and occupation of shafts and were often accompanied by violence, typically from the state and mining companies, but also what manifested as ‘ethnic rivalry’ or ‘faction fighting’. Labour struggles on the mines occurred throughout the twentieth century, but there were three key moments of major confrontation between workers and the Chamber of Mines: 1920, 1946 and 1987.

Of great significance was the 1920 strike, which lasted a week and involved more than 70 000 workers. At its height, 46 000 workers stopped work on one day.37 According to Philip Bonner, the underlying cause of the historic strike was that wages had simply not kept up with inflation: the price of basic commodities, especially food, soared during the First World War, while wages remained low. Migrants’ burdens were made heavier by impoverishment in the rural areas.38 A salient feature of these struggles was the absence of trade unions among migrant workers and their consequent reliance on izibonda (hostel-based representatives of migrant workers) and other networks in the compounds to raise grievances and organise strikes. These networks remained crucial in the lives of migrants in the compounds, even when unions took root. In fact, the success of unions often depended on their ability to work with and even rely on these structures.

Several efforts in the 1930s by left-wing activists to organise African migrants on the mines came to nought, but in the early 1940s, the African Mine Workers’ Union (Amwu) was established, mainly through the efforts of the CPSA. The CPSA was especially successful in recruiting young African workers into its ranks through its popular night schools, which exposed participants to the ABCs of Marxism. Amwu’s annual conference in April 1946 demanded a minimum wage of 10 shillings a day, adequate food and decent accommodation and within days thousands of workers were involved in demonstrations and work stoppages in support of the demand. Matters came to a head in August when the employers refused to accede to these demands. In response, 75 000 African miners joined the strike.39 This was a massive show of force and involved an unprecedented mobilisation of migrant workers. According to William Beinart, ‘the internal organisation of the strike depended on [migrant] networks … rather than the union itself’.40 However, it did mean that the union had only a relatively weak presence in the hostels. The state and Chamber of Mines immediately unleashed violence against the strikers: more than 1 000 were arrested, 1 250 injured and 13 killed. As a result, the strike and Amwu were smashed. It would take more than three decades before another union could establish itself among African miners. In fact, the violent suppression of this strike meant that miners were not involved in the creation in the 1950s of a new African workers’ federation, the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu). Nonetheless, migrants were active in other unions belonging to Sactu and were influential in supporting the alliance with the political organisations linked to the Congress Movement.

Migrant workers on the mines were not initially part of the resurgence of trade unionism in the 1970s. However, struggles did take place on the mines on a range of grievances. For example, in September 1973, machine operators at Anglo American’s Western Deep Levels downed tools to voice their objection against perceived unfair wage increments. Disputes were often concentrated in the compounds and focused on conditions and measures of control imposed in these prison-like spaces. In 1971, only one such dispute was recorded, but in 1974, this figure had increased to 35.41 Desertions, historically an important form of indirect protest, increased from 10 000 during 1970 to 50 000 during 1977.

Figure 16.2

Migrant hostel dwellers often held onto rural customs and joined rural-based organisations.

David Goldblatt

Mineworkers at their hostel, Western Deep Levels, Carltonville 1970

David Goldblatt, courtesy of the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Attempts by mining companies to increase the differential in wages paid to different categories of worker triggered disputes as workers became more conscious of wage inequalities. In September 1973, 200 machine operators at Western Deep Levels went on strike over wages. The mine bosses responded by calling in the police, causing a bloody confrontation, during which 12 mineworkers were killed. According to David Hemson, Martin Legassick and Nicole Ulrich, this event ‘precipitated a series of incidents on the Witwatersrand and the Free State lasting until 1976, in which strikes alternated with “ethnic” conflicts, with struggles by foreign African workers, and with uprisings in which beer halls, offices and compounds were destroyed’.42 Disputes on the mines continued to be largely localised and ephemeral and, by the end of the 1970s, showed little evidence of translating into formal union organisation. But change was in the air and, in the early 1980s, the big battalion of mineworkers finally joined the process of creating a new, independent and militant trade union.

The birth of the National Union of Mineworkers

After reaching record levels in the 1970s, the price of gold plummeted in the early 1980s, from $800 an ounce in 1980 to $300 in 1982. The ensuing profit and balance of payment crises directly threatened the jobs of thousands of mineworkers, especially at marginal mines. For example, when production was cut back at the West Rand Consolidated gold mine, 3 340 jobs were lost.43 Not surprisingly, discontent over wages and retrenchments simmered across the sector. Matters came to a head in June 1982 when the Chamber of Mines announced its annual increases to minimum wage levels. Two of the conservative mining companies, Gencor and Gold Fields, decided to adhere to the proposed increases, while other companies, such as Anglo American, instituted higher increases. Within days, approximately 40 000 black workers at Gencor and Gold Fields mines went on strike to demand higher wages, making it the largest strike by black miners since 1946. In typical fashion, management refused to concede to the workers’ demands and used force to end the strike, including the deportation of 2 000 workers.

Despite what appeared to be a rather typical outcome of a strike by black miners, the Chamber of Mines did seem to recognise that unionisation was probably inevitable. However, like their counterparts at the helm in Johannesburg, the mine-owners decided to recognise the Black Mine Workers’ Union, which had very little support among miners. And, following the example set by the municipal workers in 1980, black miners sought to establish an independent union. They approached the Council of Unions of South Africa (CUSA), which appointed Cyril Ramaphosa to head the process of forming a new miners’ union. With assistance from experienced miners, such James Motlatsi, Puseletso Salae and Alfred Mphahlele, sufficient support was mobilised for the new union to be launched in August 1982. When the inaugural congress was held in December 1982, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) could boast a membership of 14 000 located in nine branches, overwhelmingly on Anglo American mines.44 Within a year, NUM had built a presence in close to 50 mines with a membership of 55 000. When Cosatu was launched in December 1985, NUM claimed a membership of 250 000, making it the largest union by far in the new federation and at its fifth national congress in 1987 it reported a signed-up membership of 344 000.45 This phenomenal growth was inspired by the rapid development of independent unions and was based on organising in the compounds and shafts.

Driven by migrant workers’ desire to transform power relations on the mines and to improve their working conditions, NUM quickly found itself involved in a range of struggles, including several wildcat strikes. Workers now demanded action against white authority on the mines: in January 1984, 1 400 miners at Gencor’s Impala Platinum protested against racism and in February 1985, more than 11 000 workers at East Driefontein went on strike over ill-treatment by white miners. Wages remained a central concern with spontaneous strikes occurring all over the Rand. For example, in June 1984, 5 500 workers at Douglas, Kriel and Goedehoop collieries went on strike for ten days for higher wages and in 1985, more than 42 000 workers went on strike for two days at Vaal Reefs over wages.46

Thus, within the short period of three years, more than 100 000 migrants on the mines were involved in industrial action over a range of demands, thereby posing a serious challenge to the historic labour regime on the mines. The state and some mining houses responded with violence. Police broke up a strike at East Driefontein, which resulted in 145 injuries and 813 dismissals. Gencor, with the support of the Bophuthatswana government, violently smashed a strike at one of its mines and dismissed 23 000 strikers.47 This violence reflected the growing hostility by the mining houses to the challenge posed by NUM and set the scene for a major confrontation between these protagonists.

In 1987, the NUM demanded a 30 per cent wage increase, holiday leave of 30 days and recognition of 16 June as a paid holiday. When the Chamber of Mines rejected the wage demand, 340 000 black miners, representing more than 70 per cent of the workforce, went on strike. The strike of August 1987 was a crucial test of strength between migrant workers and their union pitted against the country’s most powerful employer body. It turned out to be a bitter conflict as the state and Chamber employed every available strategy to defeat the strike, such as lock-outs, assaults on compounds, arrests, raids on union offices, dismissals and the recruitment of scab labour. By the third week of the strike, 9 workers had been killed, 500 injured and 54 000 strikers dismissed.48 The NUM leadership called off the strike when it became apparent that the Chamber was preparing to dismiss the entire workforce. Workers did not win their demands and undoubtedly suffered a heavy defeat. However, the organisation that had been built by migrant workers remained largely intact. Unlike in the defeat of 1946, African miners were not driven into submission and within a couple of years rebounded from the defeat to embark on new struggles, contributing to the pivotal role played by the union movement in overcoming apartheid.

Conclusion

Following the strike wave that hit the platinum industry in 2012 and especially the Marikana massacre, in which 34 miners were killed by the police, renewed interest has been generated in the position of migrants in the mining industry. The continued existence of the migrant labour system has especially come in for criticism. Efforts over the past 20 years to re-orient the country’s economy to a more solid industrial base have consistently faltered. Instead, as Hein Marais has explained, the economy ‘remains excessively dependent on the minerals-energy-complex (MEC)’.49 Export of minerals remains a determining feature of the country’s location in the global economy and a crucial source of national income. As a result, it may be argued, the industry’s historical reliance on cheap migrant labour has been allowed to continue, despite strident critiques of the adverse effects of the system on migrants and their families. ‘The hard reality,’ Gavin Hartford recently insisted, ‘is that the pattern of migrant labour super-exploitation – characterised by 12 long months with only a Christmas and Easter break – has remained unaltered in the 18 years of democracy.’50 However, it is important to recognise that many migrants (including those who live in urban settlements and have ‘secondary’ wives and families) remain strongly connected to rural areas. These they regard as their primary homes, where they have extended families (who are often heavily reliant on their remittances) and where they regularly invest some of their meagre resources in homesteads.

One of the most important changes effected since 1994 is the demise of the traditional hostel system. Despite initial opposition from some migrants and the Inkatha Freedom Party, a major programme of converting hostels (especially in urban areas) into family units has been undertaken. As a result, the proportion of single migrants in these areas has decreased. However, a different picture has emerged on the mines: here migrant workers have been offered a living-out allowance, which allows them to establish a basic household in residential areas (mainly poverty-stricken informal settlements) surrounding the mines. Invariably, they now have to maintain two households (characterised by endemic unemployment), placing enormous pressure on their incomes. These are some of the factors that have once again placed migrant workers at the forefront of a new wave of industrial militancy. Echoing experiences of an earlier period, migrants have mobilised their rural networks to create workers’ committees located in the shafts (in the absence of the hostels) and have turned against their traditional union, NUM. In so doing, migrant workers have potentially inaugurated a process of reconfiguring the landscape of trade unionism in the country. As before, migrants seem to be reclaiming their role as vanguards of the workers’ struggle.

Figure 16.3

NUM grew rapidly in the 1980s to become the largest independent black trade union in the country.

Paul Weinberg

Workers gather at a NUM Annual Congress, Johannesburg

1986

William Matlala, photographic collection at Historical Papers Research Archive, The Library, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

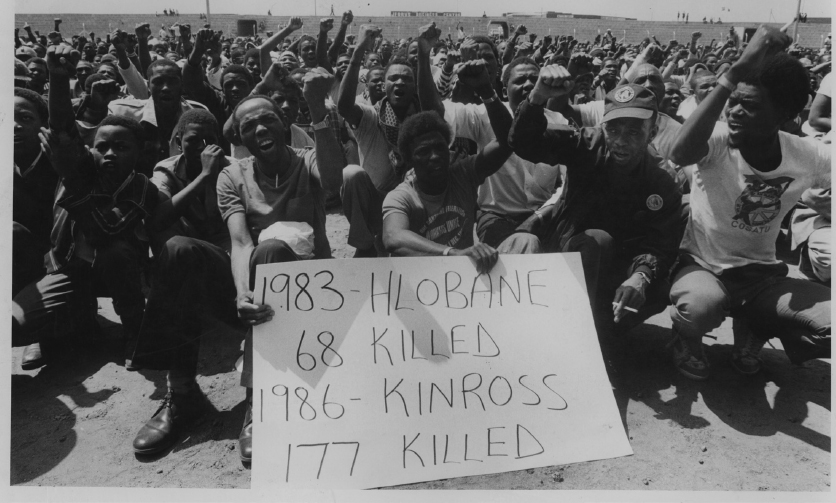

Figure 16.4

Deaths on the mines were a key rallying point for NUM’s mobilisation of migrant workers.

Paul Weinberg

NUM workers at a rally protesting against the death of miners, Johannesburg 1986

Historical Papers Research Archive, The Library, University of the Witwatersrand

Figure 16.5

The strike wave on the platinum mines in 2012 inaugurated a new phase of unionisation among migrant workers.

Oupa Nkosi

Striking mineworkers at Marikana 2012

C-print

47 × 59 cm

Collection of the artist

Notes

1. East Rand worker poet, quoted in K Forrest, Metal That Will Not Bend: National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, 1980–1995 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2011), 89.

2. P Delius, A Lion Amongst the Cattle: Reconstruction and Resistance in the Northern Transvaal (Johannesburg: Ravan Press; Portsmouth: Heinemann; Oxford: James Currey, 1996), 37.

3. W Beinart, ‘Worker Consciousness, Ethnic Particularism and Nationalism: The Experiences of a South African Migrant, 1930–1960’, in The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century South Africa, eds. S Marks and S Trapido (London: Longman, 1987), 289–291.

4. R Turrel, Capital and Labour on the Kimberley Diamond Fields, 1871–1890 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 45, 146.

5. Delius, Lion, 176.

6. D Hemson, M Legassick and N Ulrich, ‘White Activists and the Revival of the Workers’ Movement’, in The Road to Democracy in South Africa, Vol 2 (1970–1980), South African Democracy Education Trust (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2006), 254.

7. S Friedman, Building Tomorrow Today: African Workers in Trade Unions, 1970–1984 (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987), 37.

8. J Brown, ‘The Durban Strikes of 1973: Political Identities and the Management of Protest’, in Popular Politics and Resistance Movements in South Africa, ed. W Beinart and M Dawson (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2010), 31.

9. J Maree, ‘Overview: Emergence of the Independent Trade Union Movement’, in The Independent Trade Unions, 1974– 1984: Ten Years of the South African Labour Bulletin, ed. J Maree (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987), 2.

10. E Webster, Cast in a Racial Mould: Labour Process and Trade Unionism in the Foundries (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985), 131.

11. Forrest, Metal, 11.

12. Ibid., 12–14; Hemson, Legassick and Ulrich, ‘White Activists’, 257–260.

13. D Horner, ‘The Western Province Workers’ Advice Bureau’, in Independent Trade Unions, ed. Maree, 12–13.

14. Hemson, Legassick and Ulrich, ‘White Activists’, 262.

15. Horner, ‘Western Province’, 14; Hemson, Legassick and Ulrich, ‘White Activists’, 261–262.

16. T Carson, ‘The Fatti’s and Moni’s Strike’, in Popular Politics, eds. Beinart and Dawson, 55.

17. L McGregor, ‘The Fatti’s and Moni’s Dispute’, South African Labour Bulletin (hereafter SALB), 5.6 & 7 (1980), 123–125.

18. J Baskin, ‘The 1981 East Rand Strike Wave’, SALB 7.8 (July 1982), 22–24.

19. Delius, Lion, 142.

20. Forrest, Metal, 39.

21. Ibid., 41.

22. Ibid., 86–90.

23. Ibid., 93 and 121.

24. J Keenan, ‘Migrants Awake: The 1980 Johannesburg Municipality Strike’, SALB 6.7 (May 1981), 4.

25. Ibid., 10. According to the Labour Research Group, the number of contract workers stood at 8 000. See Labour Research Group, ‘State Strategy and the Johannesburg Municipal Strike’, SALB 6.7 (May 1981), 65–67.

26. Keenan, ‘Migrants Awake’, 19.

27. Ibid., 25.

28. Ibid., 27–35.

29. Ibid., 11.

30. Labour Research Group, ‘Johannesburg Municipal Strike’, 76.

31. According to Gerald Kraak, about one in eight African workers in 1985 was employed in mining. See G Kraak, Breaking the Chains: Labour in South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s (London: Pluto Press, 1993), 91.

32. J Crush, A Jeeves and D Yudelman, South Africa’s Labour Empire (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991), 234–235.

33. Ibid., 86.

34. Kraak, Breaking the Chains, 93.

35. VL Allen, The History of Black Mineworkers in South Africa, Volume III: The Rise and Struggles of the National Union of Mineworkers, 1982–1994 (Keighley: The Moor Press, 2003), 15.

36. Kraak, Breaking the Chains, 98.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid., 279–281.

39. B Hirson, Yours for the Union: Class and Community Struggles in South Africa (London: Zed Books, 1989), 182–185.

40. Beinart, ‘Worker Consciousness’, 296.

41. Allen, History, 340–341.

42. Hemson, Legassick and Ulrich, ‘White Activists’, 266.

43. Allen, History, 86.

44. Ibid., 99.

45. Ibid., 236.

46. Ibid., 116, 119, 155 and 156.

47. Ibid., 169.

48. Ibid., 385.

49. H Marais, South Africa Pushed to the Limit: The Political Economy of Change (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 2011), 132.

50. G Hartford, ‘The Mining Industry Strike Wave: What Are the Causes and What Are the Solutions?’ GroundUp, available at http://groundup.org.za/content/mining-industry-strike-wave-what-are-causes-and-what-are-solutions.