Migrant workers from Mpondoland have been characterised as traditionalist and fiercely attached to their rural homes. Yet mineworkers from this area came into the national news in August 2012 as both strikers and victims of the shootings at Marikana Platinum Mine. Of the 45 people killed at Marikana, 30 came from Mpondoland and nearby districts of the Eastern Cape/ former Transkei. Their deaths raise questions about their history and their politics. While it is important not to ethnicise a diverse segment of the South African workforce, or the strikes themselves, I suggest that a sense of collective identity has, in part, shaped their experiences of migration over the long term.

Labour migrancy and the rural economy

Historians have analysed different patterns of migrant labour in southern Africa, but it is still difficult to distinguish the forms of consciousness and organisation that arose amongst specific groups and networks of migrants. Migrants from Mpondoland were, in part, distinctive because the Mpondo chiefdom was, in 1894, amongst the last to be annexed in South Africa as a whole. They were not conquered by force, lost little of their land to settlers and were pushed into wage labour at a later stage than other African societies. Most families maintained access to arable plots, as well as grazing for their livestock, until far into the twentieth century. Since the region is blessed with high rainfall, smallholder agriculture was relatively effective, at least until the 1960s. Mpondoland comprised only 7 of the 26 old Transkeian districts (the number rose to 28 in the 1970s when the homeland was consolidated). Yet although they were sometimes categorised as Xhosa in the homeland era, Mpondo people retained their identity, as well as separate paramount chiefs and regional political authorities.

Until the 1960s, Mpondo migrants characteristically worked underground on the gold mines and as canecutters in the Natal sugar fields.1 In general terms, their experience differed from rural isiZulu-speakers to the north, who tended to avoid long phases of underground work and cane-cutting; they worked in mills or migrated to Durban or Johannesburg. Those to the south, in the western Transkeian and Ciskeian districts, gravitated more to the Cape ports, working on the docks and in a wide range of urban employment. Bhaca workers from Mount Frere, neighbouring Mpondoland, specialised for some decades in night-soil removal and municipal employment in Durban and on the Witwatersrand.

Numbers of workers migrating annually from the seven (old) districts increased from about 2 000 in 1896 to 10 000 in 1910, to 20 000 in 1921 and 30 000 in the 1936 census. By then, roughly two-thirds worked on the mines and most of the rest – especially younger men – in the sugar fields. By the 1930s, more than 40 per cent of men between the ages of 15 and 45 were absent from their homes for work annually. As workers tended not to migrate every year, long-distance migrancy had become an experience general to most men in Mpondoland. Initially, many mine migrants accepted prepayment from labour agents in livestock, thus ensuring that the bulk of their earnings never left home (and could potentially reproduce while they were away). Although this was abolished on the mines in 1910 because it was linked with desertion, advance payments remained available from some sugar recruiters. Mgeyana Ngumlaba told me in 1977:

I never put my foot in school. I never saw a school here in Msikaba in those days. The church was not here … It was joyin’inkomo [recruiting with cattle] at that time. You used to get a beast from Mr Strachan … and then go forward. This was done after East Coast fever and these are the cattle we got after East Coast fever. I went to the sugar fields … before getting married in 1920. I preferred to go to the sugar rather than the mines [as] … I could join and get a beast … I worked six months for a young heifer [itoli] … I went to the sugar fields because I wanted a beast … There was an Indian foreman who was in charge of us and he beat us. That is how it was in those days. My intention was to get that beast. I was not interested in what was happening to me.2

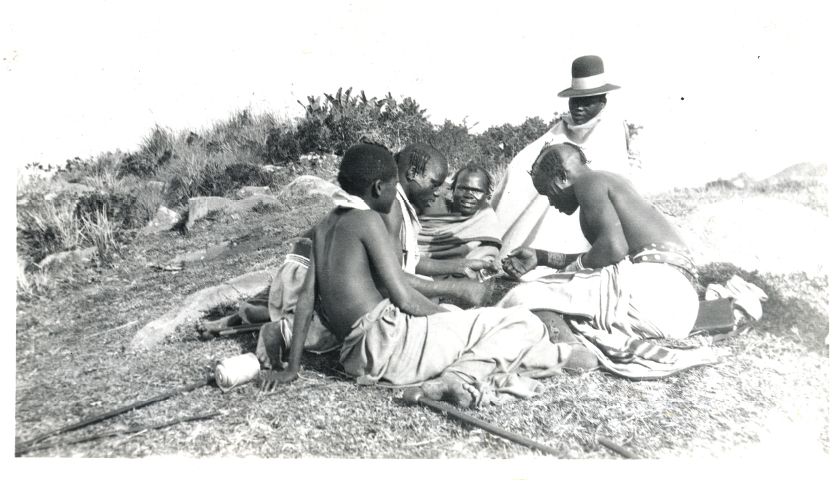

Figure 4.1

Monica Hunter

Xhosa miners back from the mines playing cards

1932

Wits Museum of Ethnology Photography Collection, Wits Art Museum

The advance system and testimonies such as the one above led me to argue that many men from the region initially saw the migrant labour system as a means of accumulating livestock, paying part of their bridewealth and building their rural homesteads. In fact, Mgeyana later returned to the sugar fields, taking cash contracts that provided a better deal. He avoided the mines because he felt the contracts were too long:

I only went away five times. I bought cattle with the money from the sugar fields. The cattle were cheap in those days … I bought nine and also got other cattle that were paid … as bride-wealth for my sisters. I bought clothes for my sisters and bought blankets for my father. I bought saddles and bridles. I was wearing blankets myself. I bought a plough from the money from the sugar fields. I came back here and got married and got fields but I was working first on my father’s fields … I am the man who buried my father. I have always got enough mealies [maize] to keep my family ... My father did not drink tea; those things have just come now.

Migrancy became embedded in the expectations of young men. I once asked an old headman, Meje Ngalonkulu, who was more than 90 years old when I interviewed him in 1982, ‘Could you not loan cattle?’3 ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but I did not want to.’ Loaning cattle also carried risks and responsibilities because a portion of the increase had to be paid back. ‘However rich the father was, the son must go out to work,’ he said. ‘Even if the father could pay the bride-wealth in full?’ I asked. ‘Well that was not the practice when the sons started to work,’ he responded. ‘The father must help, but the sons must pay some.’ He had bought cattle from other people and paid seven for his bride-wealth, to which his father added four. Thus earnings from migrant labour were gradually incorporated into the very reproduction of the homesteads. The amount paid in bride-wealth also increased: ‘Before it was two or three, but when people started going to work, it was 10 or 12 – and this was for ordinary people.’4

Even by the 1940s, when men were taking more regular contracts on the mines, Native Recruiting Corporation records show that 45 per cent of recruits from Mpondoland deferred their pay in full and 60–70 per cent of the total earned by recruits from these districts was repatriated. Earnings from migrant labour were important for family subsistence, but also helped to sustain the rural economy through investment in livestock and arable production. Migrancy became necessary for most families, in order to pay taxes and purchase what became seen as necessities. However, contrary to some early analyses that saw migrancy as symptomatic of the collapse of rural production, evidence suggests that there was initially a positive, rather than inverse relationship between wage income and smallholder output.

We can explore this in two ways – as an aggregate and with respect to individual homesteads.

In Table 4.1, the 1914 figure shows cattle herds devastated by East Coast fever, but by 1932, numbers had reached 521 000 – almost certainly at an all-time high. Booming livestock numbers, facilitated by dipping against tick-borne diseases, coincided closely with the rise in migration. Cattle prices were low at this time, so wages went further if invested in livestock. Production of maize (Table 4.2) also doubled in the early decades of the twentieth century, so that 1939 (at 810 000 bags) was probably the all-time peak year.

In the aggregate, the standard of living for Transkeian families, especially in the Mpondoland districts, probably improved until the 1930s. The positive relationship between migrant earnings and agricultural production continued until the 1960s – and possibly longer. Although aggregate production probably then declined, surveys emphasise the continuing link between wage income and investment in agriculture for individual homesteads. In Tsolo in 1976, families earning above R40 per month cultivated three times more land than those earning R10–20 and they also got slightly higher yields; similar correlations were found in Matatiele and in Libode in the 1980s.5 Since the 1990s, however, this relationship seems to have broken down for arable production, even in wealthier homesteads.

Migrant identities, rural families and associational life

In Going for Gold, Dunbar Moodie attempted to identify different ‘migrant cultures’ on the mines, based on interviews conducted in the 1970s. He records that ‘miners from other groups talk of the proverbial stinginess of the Mpondo’, who were there ‘on business’.6 Following the analysis of Philip and Iona Mayer of the relative ‘encapsulation’ of traditionalist migrant workers in East London, Moodie argued that his Mpondo interviewees shared a ‘commitment to the independence and satisfactions of patriarchal proprietorship over a rural homestead’ and that this ‘implied resistance to proletarianisation’. Their social and economic base in the rural areas remained a priority and manhood ‘was achieved essentially in presiding justly, wisely, and generously over an umzi, or rural homestead’.7

Table 4.1 Average cattle holdings in seven Mpondoland districts

Year |

Number of cattle |

1904 census |

135 000 (still recovering from Rinderpest) |

1911 census |

280 000 |

1914 |

76 000 (after East Coast fever) |

1910s |

127 000 (number of figures =5) |

1920s |

312 000 (n=10) |

1930s |

500 000 (n=10) |

1940s |

453 000 (n=10) |

1950s |

401 000 (n=10) |

1960s |

400 000 (n=3 – published series ceases after 1963) |

Table 4.2 Average maize production in seven Mpondoland districts

Year |

Number of bags of maize |

1920s |

545 000 bags (n=7) |

1930s |

544 000 bags (n=7) |

1940s |

542 000 bags (n=4) |

1950s |

499 000 bags (n=10) |

1960s |

627 000 bags (n=5) |

Source: Figures taken from the Census, Agricultural Census and Transkeian Territories General Council reports

Migrants from Mpondoland, however, also absorbed cultural practices and patterns of masculinity forged in underground work and the compounds that, in some respects, mitigated the harshness of conditions on the mines. They were known for their clannish behaviour and assertiveness. When I conducted interviews in the 1970s, I was not especially looking for such material, but it was sometimes forthcoming. Xatsha Cingo remembered: ‘The Mpondo were in their own rooms; the Xhosa lived separately. It was all right as long as a man was Mpondo, it did not matter if he was from Nyandeni [Western Mpondoland] but no Xhosa were allowed. We were not on good terms.’8 The language of difference between Mpondo and Xhosa on the mines was often remembered as focusing on circumcision. In the nineteenth century, the Mpondo, as in the case of the Zulu kings, abolished male circumcision, which remained central to most African societies in the region. Lionel Mathandabuzo from Lusikisiki recollected that ‘when they go to the mines, they meet with the Xhosas and they are insulted as boys.’9 Leonard Mdingi, from Bizana, worked for four contracts on the mines in the 1940s and blamed employers for the strength of ethnic identity. But he recognised the sense of difference: ‘When the Xhosas speak of Pondos as boys, the Pondos don’t take it seriously. Because the Xhosas want the Pondos to adopt their customs and the Pondos don’t want that.’10

Moodie analysed the way that collective action by miners in the compounds enabled them to forge some space and influence over their lives. These solidarities could also result in conflict and Mpondo workers were perceived to have a predisposition to violence. Mdingi recalled:

Mostly these fights took place this way. A group of Pondos, Sunday they go out beer-drinking. And now when they come back they meet a group of Basutos. And the Basutos attack the Pondos. They hit them hard. Some Pondos go to hospital, and others run away … when these Pondos come back, heads bleeding and all that, they hear that the Basutos have done this. Now the Pondos … they start arming, and attack the Basutos. Not the Basutos who did this but all the Basutos … The thing starts up.

A minority of workers were drawn into the gangs spawned by compounds and prisons. From the 1920s until the 1940s, the Mpondo-based Isitshozi were seen as particularly violent.11 Keith Breckenridge suggests that they probably amalgamated first in Cinderella prison and then established themselves in the nearby East Rand Propriety Mine compound, which drew in many workers from Mpondoland. Cinderella was a major receptacle for African workers convicted on the East Rand and became known for gangs. While part of the gang’s criminal activity was aimed at the city beyond the compounds, breaking into houses and mine concession stores, it drew on the resources of the compound. The Isitshozi copied a hierarchy of posts from the earlier Ninevites organisation that developed in the Rand’s prisons – General, Judge, Landdrost, Captain, Sergeant and Corporal. Loyalty and discipline were central and gang members were able to gain access to compound resources and homosexual relationships through violence and the threat of violence. Their favoured weapon was a sharpened rock drill. Some members conceived the Isitshozi as necessary for protection against other gangs, such as the Sotho-dominated Russians, who in turn saw Mpondo gangs as a threat. In this period, they seem to have contributed to ethnic tension on the mines.

Dangerous and difficult work produced a strong sense of camaraderie and underground teams often cut across ethnic identities. But, after their shifts, miners went back to the compounds. At weekends ‘mine workers travelled all over the Witwatersrand on foot and by train, visiting, eating and sleeping with friends from home at other compounds’.12 From their vantage point, ethnic networks were a means of socialising, as well as a route to protection. Moodie explores the differences, in migrants’ minds, between waged work for Europeans and work for the homestead. In his and other analyses, work for the homestead is generally seen as more positive. Migrants had to find ways of amalgamating both experiences towards the larger goal of building a rural base.

Figure 4.2

Margaret Bourke-White

Native Pondo tribesmen recruits for Johannesburg gold mines waiting next to passenger train as they prepare to embark at railroad station, Umtata, Transkei

1932

Courtesy of Time/Life Pictures, Getty Images

We should, however, be cautious about romanticising the umzi and the relationships within it. Wages from migrant labour gave younger men the opportunity to establish their independence earlier, both in spatial and personal terms. The scale of evidence about youths escaping parental control from the 1920s to the 1940s suggests that by no means all were migrating as part of a collective endeavour to support their homesteads. Some young men, at least, wished to get away from family labour. Mcetywa Mjomi recalled: ‘It was very easy to join in those days. Boys ran away from herding cattle. They were doing it without the permission of their parents – who were complaining about it. Sugar recruiters would approach them and would send someone to collect the boys.’13 This term ‘ran away from herding’ came up quite frequently in my interviews. It could be demanding work and though it was usually shared in a group, it was unpaid and punishment could be meted out if livestock were lost or injured. African homestead heads in more traditionalist districts assumed that child labour was available for their use: ‘We require our boys to herd our stock, yet they can run away from us by doing this.’14 Phatho Madikizela recalled of his youth in the 1940s:

I had to hide away because I was running away from school … I thought I would be rich in no time if I left school and went to work. When I arrived there [Tongaat], I had to clean the stables where the mules were kept. I liked that work because it was not hard. When I returned my father was angry.15

Alfred Qabula, later a trade unionist, wrote of his childhood in Mpondoland during the 1940s:

Figure 4.3

Mrs Fred Clarke

Migrant workers returning from the gold mines

Date unrecorded

Campbell Collections, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal

As a child I was taught to respect my elders, the hard way … You see my parents did not just give us a good hiding. They would almost kill us if we did something wrong. Our father was a very strict man. He was a miner at Egoli and loved his drink, and he had a very short temper … All I remember is his horse and his horse’s gallop. Though I can’t remember what I had done wrong I can still recall all those days when he was chasing me on horseback: to kill me, I thought.16

In his case, he remembered herding more positively, as a social pastime:

It was fun to be a herdboy, we loved the fights and the adventures in the wild. That is where we got to know the heroes of childhood. We used to know that so and so is an expert at stickfighting, so and so is a coward, and so and so can’t defend himself.

Yet this mix between demanding elders and relative freedom, as well as strong and rather discrete youth associations, may help to explain why youths rebelled against working for the homestead. There are contemporary echoes, in that young men now avoid work in agriculture and even in herding, despite high unemployment and the availability of land. It appears that waged work was sometimes, both then and especially now, seen in a more positive light than work for the homestead.

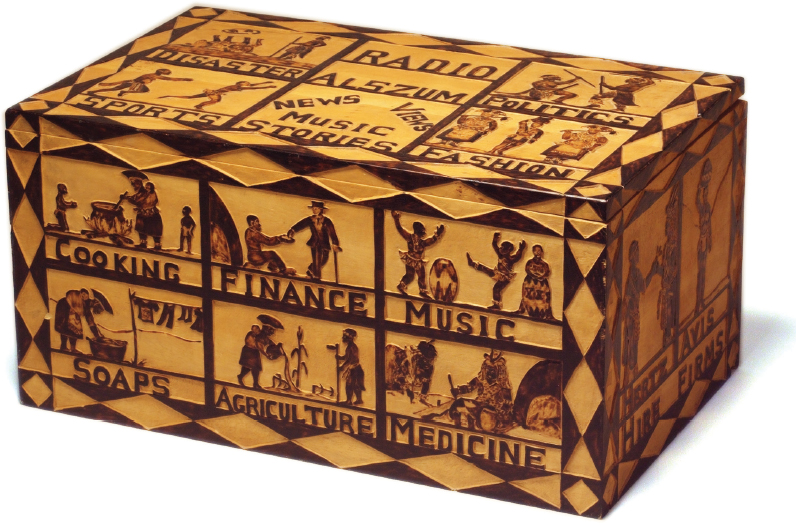

Figure 4.4

Alson Zuma

Radio Alszum

1999

Wood, poker-work, metal, casette player

30 x 59.5 x 36.5 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

An earlier generation of studies on the migrant labour system judged it not only as coerced, but also highly destructive of families.17 In many senses, this view is justified. However, a qualification should be made. In pre-colonial times, people generally lived as part of large three-generational homesteads that could include clusters of married men and their wives. While migrancy in the first half of the twentieth century did not destroy these institutions, wages gave sons the option of moving out of homesteads earlier and the units of settlement almost certainly declined in size. In certain respects, migrancy helped to form more nuclear families – though men from the same patrilineage still often tried to settle close by.

A further qualification to the idea that rural social life was breaking down may be found in some of the rural associations that emerged during the period when migrant labour was at its height. These could be analysed as evincing the destructive impact of labour migration, but the people I interviewed generally articulated a positive sense of their group experiences. Traditionalist youth associations had long been a central element in socialisation. In the 1930s, when migrancy from the area reached its first crescendo, a new men’s organisation took shape. The indlavini (youth associations, tightly organised in hierarchical, male-only, gang-like groups) probably derived their name from the word for bravado – although some also thought it was associated with their unusual dress.18 Whereas previously, all youth in a particular locality joined the traditionalist bhungu or nombola groups that arranged many social events for young women as well as men, only a limited number became indlavini. They distinguished themselves by virtue of their education (generally above Standard 2), their dress and their discipline. Traditionalist youths wore blankets, at least for major social occasions, but indlavini adopted shirts and wide bell-bottom trousers.

The indlavini groups demanded loyalty and developed a hierarchy with a leader, second in command, policemen, spies and a secretary. While they met regularly by themselves and away from village settlements, they descended on rural events, disrupting weddings and asserting their interest in local women. Essentially a rural association, they also organised leisure time for their adherents on the mines. Probably at their height in the 1950s and 1960s, they were a distinct presence for half a century, finally fading in the 1980s when urban influences increasingly suffused Mpondoland.

Alongside the indlavini, at much the same time, from the 1930s to the 1980s, amatshawe (beer-brewing and drinking) associations spread through Mpondoland. They included both women and men, but not husbands and wives. Although the general evidence suggests that most migrant men were intent on building homesteads, not all were able to do so. Some died on the mines or sugar fields, some deserted or moved into urban townships. As a consequence, wives were left behind. We should also accept that wives had agency. There had long been social routes through which women could return to their parental homesteads, or even establish small homesteads themselves. Left for long periods, or annoyed when their husbands took second wives, they could and did leave marriages or start new relationships. The term itshawe seems to have been used in the 1930s to mean such a woman in Mpondoland. It was possibly derived from the word umtsha, referring to young men as lovers. The plural of this word came to mean the collectivity of such women and men – an association with distinct practices. The women were also referred to as amadhikazi, a social category in Mpondoland and beyond, which included those who had formerly married, or at least were mothers, but without husbands. They provided the backbone of the amatshawe beer-brewing groups.

The amatshawe met at weekends, sometimes from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning. Married women were generally not allowed to attend, but migrant and married men were key to the organisation. Sorghum/maize beer was brewed for sale, food cooked, singing and dancing organised and there was an opportunity for relationships to develop. Amatshawe in the countryside offered women who were no longer married the chance of access to migrant workers’ earnings. Monica Hunter noted that in 1931–1932, ‘the class of amadikazi in Pondoland is very large, and practically every married man has his special friend among them’.19 Another anthropologist was told in 1939: ‘The number of amatshawe is growing by the day, and if it goes on as it does at present, the number of amatshawe will soon be greater than the number of married women’.20 When I was interviewing in 1988, one older woman suggested that during her lifetime, the number of amadhikazi outgrew the number of wives in Lusikisiki district.

The amatshawe also developed a hierarchy of posts, mainly occupied by men. Each local group boasted a president, magistrate or judge, policeman and doctor. They supervised the parties, controlled admissions, kept the peace, organised floats to buy supplies and ensured fair distribution of proceeds. Women could be ‘doctors’: one of the duties of such ‘doctors’ was to control the quality of the beer. While it may seem that amatshawe were marginalised women, some saw the association as an opportunity. Nomadenga Dingi in Bizana joined at the age of 43 when her husband died; the homestead was taken over by her husband’s younger brother, who chased her out and kept her cattle. ‘This was the first time I felt really free and enjoyed myself,’ she recalled.21 Qabula notes: ‘They did not fight anyone. They only lived for fun.’22 Perhaps an appropriate description would be a society of drinkers and lovers. Mpondoland was, comparatively speaking and over the long term, a society of sexual freedom – a freedom weighted in favour of men, but where women also participated and took agency.

Such amatshawe were amongst the early women migrants to the sugar fields. Hlubi Phutuma, who worked there from the 1940s to the 1960s, recalled them at Sizela, one of the major estates on the south coast: ‘There were amadhikazi from Pondoland who had piece jobs, togt (day labour) jobs. They were accommodated in the Zulu locations. They held the itshawe in the compounds.’23 Nobelungu Genuza went to Natal around 1949 to Nkosibomvu, an Mpondo-dominated compound at Tongaat: ‘They really had itshawe. Not many Zulu came because they were afraid of Mpondo and they couldn’t understand the songs.’24 Mangenqe Somi had been married only a few years when both her husband and his parents died. In 1960, she went to the sugar estates with two children: ‘I did not stay hoeing cane for very long, but switched to brewing beer and joined the amatshawe.’25

Mass migrancy was, in many senses, a socially fragmenting experience. Despite a degree of agrarian stability, the low wage regime and growing population gradually intensified poverty. Yet these and other associations provided routes by which people could collectively manage and negotiate these forces. They reinforced a sense of identity that seems to have been sharpened by conditions and encounters on the mines and sugar estates. Arguably, migrancy also intensified violence in aspects of rural life, both between groups of men and between men and women. Mpondo men came to be seen by others as violent, though there was not a uniform collective identity. Gangs and male associations grew alongside amatshawe, traditionalist groups and churches.

Durban, politics and Marikana

Even into the 1950s, when migrancy to the mines and sugar fields was dominant, patterns were never entirely uniform. Men (and increasingly women) from the same rural districts went to work in a range of different places. Leonard Mdingi from Bizana left the mines after four contracts and found work through a contact in a Durban factory in 1949. He found living in the SJ Smith compound ‘quite different’ from the mines; ‘we were just together … Zulus, Shangaans’.26 But patterns of migration became more diverse in the 1960s. Some people moved out of Mpondoland to Durban to escape government repression, following the rebellion of 1960. At the same time, industry and employment opportunities expanded rapidly on the southern side of Durban. In a sample of 676 formally employed workers in Durban at the end of the 1970s, 242 were from Transkei, mostly from the Mpondoland districts.27 Many lived in hostels, but there was massive growth of informal settlements around Durban and Pietermaritzburg from about 1979 onwards, as the pass laws broke down.

Figure 4.5

Artist unrecorded

Tsolo District, Eastern Cape

Isibexelele (beaded chest panel) belonging to Keke Sijobo

Collected 1988

Beadwork, pencils

93 × 15.5 cm

Standard Bank African Art Collection (Wits Art Museum)

Established residents sometimes resented the newcomers and this triggered one of the single most devastating incidents of violence in South Africa during the 1980s. Vigilantes linked to Inkatha in the Umbumbulu Tribal Authority on the southern rim of the Durban metropolitan area attacked an informal settlement largely occupied by Transkeians and more than 100 people were killed in December/January 1985– 1986. Thousands of shacks were razed to the ground. The local Zulu chief said: ‘The Zulu wanted first option on the jobs in the area, and on the water and the land … The Zulus said that the Pondos were killing the Zulus, as the Pondos were stealing Zulu’s jobs.’28

A number of the factories were already unionised by the new unions, which acted as a partial counterweight to the ethnic tensions. Over the longer term, the relationship between more traditionalist migrant workers from areas such as Mpondoland and unionism has been complex. Moodie suggests that workers from Mpondoland were largely peripheral to the 1946 mine strike. But there have been many routes out of the area. Both Oliver Tambo and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela came from Bizana district (now part of the OR Tambo district municipality). Individual migrant workers from the area became politicised. When Leonard Mdingi was living in SJ Smith compound, Durban, he was drawn into the Defiance Campaign, the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu). He played an important role in linking the leaders of the Mpondo revolt to the Durban ANC in 1960 and operated underground for many years. Alfred Qabula joined the ANC Youth League when he was at school in Flagstaff in 1959. After getting a job at the Dunlop factory in Durban in 1974, he became a key shop steward and a public poet for the unions. He specifically adapted praise poetry away from its connection with chieftaincy, ‘praising my brothers and sisters in the factories and shops, mines and farms’.29 Hoyce Phundulu, politicised by repression in the former Transkei, worked from 1976 to 1994 as a clerk at Hartebeestfontein Gold Mine and led the struggle to get the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) recognition. Workers from Mpondoland in Natal tended to sympathise with the United Democratic Front (UDF) during the 1980s. This fed into the conflicts with Inkatha in the Umbumbulu area and the unions were not sufficiently established or influential to contain them.

A number of workers from Mpondoland continued to migrate to the gold mines, even when rural recruiting slowed in the 1980s and the explosive growth of platinum provided new opportunities on the Rand. By 2012, platinum mines employed 180 000 workers in all and to a greater extent than with the gold mines, workers organised their own networks and transport. Those from Mpondoland (and others) who had long experience underground established themselves as rock-drill operators on some platinum mines, such as Lonmin’s Marikana. In their book on the August 2012 strike and police killings, Peter Alexander et al. suggest that ‘most Lonmin workers were oscillating male migrants from Pondoland’.30 This probably refers to the 3 000 rock-drill operators who led the strike.

There is evidence that the long-distance migrants from the Eastern Cape were experiencing particular pressures and reacted with unusual collective solidarity that went beyond union membership. The platinum mines were not particularly concerned to house their workers in compounds and they offered small livingout allowances, which increased the cash income of migrants and seem to have been attractive to them. As the surrounding towns offered no cheap housing, many ended up living in shacks. Gavin Hartford argues that the spiralling costs of maintaining these second, urban homes – including urban girlfriends and dependents – in part, drove migrants to strike. He speaks specifically of workers from the ‘Pondoland villages of Lusikisiki and Flagstaff’ – although it is not clear whether he has interviewed such workers directly.31

Micah Reddy’s recent interviews with Transkeian migrants on the platinum mines suggest that most of them still remain committed primarily to their rural homes.32 Even if their urban homes are not the key problem, the rates of unemployment in rural districts are such that ‘migrants are … seen as monied men and are obliged to act as providers in their community. Their wages are stretched thin as they fend for their many dependents and plough what they can afford into educating future generations.’33 Big social events, such as funerals, are also a drain on migrant wages and my interviews in a rural Mpondoland village (2008–2012) indicate that while there is little communal action in agricultural production any longer, such collective consumption is common.34 The cost of food in the rural areas spiralled in the period before the strikes, as global maize prices doubled in the two years before August 2012. Food costs are no longer significantly reduced by local arable farming. The major investment in rural villages tends to be in buildings, education and livestock, rather than crop-production.

The strikes at Marikana emerged from complex causes, not least of which were the differential wage settlements reached by other companies that triggered dissatisfaction among rock-drill operators working at Lonmin mines. Unlike the gold mines, platinum companies had not attempted to negotiate industry-wide agreements. Urban costs and the lack of services for the shack settlements around the mines undoubtedly fed into discontent at a time of rising street protests. Rock-drill operators started to desert the NUM, seeing its leadership as too close to the mining industry, too self-interested and too committed to complex negotiation of stratified wages. Some joined the new Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, in the hope of finding more militant representatives who were closer to the miners. The strike, however, was organised by neither union. It was the solidarities of the migrant workers, perhaps partly drawing on rural and ethnic identities, as well as common experiences at work, that seem to have given them collective momentum. Commentators note that miners recalled the hill committees of the Mpondo revolt when they retreated to a rocky outcrop near Marikana. They supported a flat-rate wage increase across a range of different work categories. This suggests solidarities that were not born directly from the NUM.

Conclusion

The early phases of radical historiography emphasised the drama of industrialisation, dispossession and the successful wrenching of a labour force from a declining peasantry. Migrant labour was seen to be a particularly exploitative system. This view was modified by those writing on discrete rural areas who were struck by rural resilience and the reinvestment of wages into homesteads. Proletarianisation had been incomplete; African rural communities retained some of their cultural identity. From the vantage point of the early twenty-first century, the scale of urbanisation and the transformation of the rural areas must be accepted as overwhelmingly important features of South African history. But there remain some striking continuities. Investment in rural houses and, to some degree, in livestock persists and events at Marikana suggest that the rurally based solidarities of migrant workers from Mpondoland and neighbouring districts, though very different from those prior to the 1960s, are still discernible.

Notes

1. W Beinart, The Political Economy of Pondoland 1860–1930 (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1982).

2. Interview with Mgeyana Ngumlaba, Lusikisiki, 14 January 1977.

3. Interview with Meje Ngalonkulu, Bizana, 7 April 1982.

4. For bride-wealth inflation, see C Murray, Families Divided: The Impact of Migrant Labour in Lesotho (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

5. W Beinart, ‘Transkeian Smallholders and Agrarian Reform’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies 11.2 (1992), 184.

6. TD Moodie, with V Ndatshe, Going for Gold: Men, Mines, and Migration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 33.

7. Moodie, Going for Gold, 2–3.

8. Interview with Xatsha Cingo, Lusikisiki, 1977.

9. Interview with Lionel Mathandabuzo, Lusikisiki, 23 February1977.

10. Interview with Leonard Mdingi, Bizana, 3 June 1982.

11. K Breckenridge, ‘Migrancy, Crime and Faction Fighting: The Role of the Isitshozi in the Development of Ethnic Organisations in the Compounds’, Journal of Southern African Studies 16.1 (1990), 55–78; W Beinart, ‘Worker Consciousness, Ethnic Particularism and Nationalism: The Experiences of a South African Migrant, 1930–1960’, in The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century South Africa, ed. S Marks and S Trapido (London: Longman, 1987), 286–309.

12. Moodie, Going for Gold, 23.

13. Interview with Mcetywa Mjomi, Bizana, April 1982.

14. Pondoland General Council, 1929, 57–58: speech by Councillor Soxujwa, Lusikisiki.

15. Interview with Phatho Madikizela, Bizana, April 1982.

16. AT Qabula, A Working Life, Cruel Beyond Belief (Durban: University of Natal, 1989).

17. F Wilson, Migrant Labour in South Africa (Johannesburg: South African Council of Churches, 1972).

18. W Beinart, ‘The Origins of the Indlavini: Male Associations and Migrant Labour in the Transkei’, African Studies 50.1 and 2 (1991), 103–128.

19. M Hunter, Reaction to Conquest (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), 206.

20. J van Tromp, ‘Amatshawe among the Amampondo’, November 1939 in D Hammond-Tooke’s research notes, copied for the author.

21. Interview with Nomadenga Dingi, Bizana, July 1988.

22. Qabula, Working Life.

23. Interview with Hlubi Phutuma, Bizana, August 1988.

24. Interview, Vivienne Ndatshe with Nobelungu Gunuza, 28 March 1989.

25. Interview, Vivienne Ndatshe with Mangenqe Somi, March 1989.

26. Interview, Mdingi.

27. FP Christensen, ‘Pondo Migrant Workers in Natal: Rural and Urban Strains’, MSocSc thesis, University of Natal, Durban, 1988.

28. Ibid., 101.

29. A Sitas, ‘The Moving Black Forest of Africa’, in Rural Resistance in South Africa: The Mpondo Revolts After Fifty Years, ed. T Kepe and L Ntsebeza (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 2012), 173; see also TD Moodie, ‘Hoyce Phundulu’, in the same collection, 143–164.

30. P Alexander, T Lekgowa, B Mmope, L Sinwell and B Xezwi, Marikana: A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2012), 190.

31. G Hartford, ‘The Mining Industry Strike Wave: What Are the Causes and What Are the Solutions?’ October 2012, http://www.polity.org.za/article/the-mining-industry-strike-wave-what-are-the-causes-and-solutions-october-2012-2012-10-09.

32. M Reddy, ‘Unrest on South Africa’s Platinum Mines and the Crisis of Migrancy’, MSc thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, 2013.

33. Ibid., 31.

34. W Beinart and K Brown, African Local Knowledge and Livestock Health: Diseases and Treatments in South Africa (Woodbridge: James Currey; Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2013).