CHAPTER 7

The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa’s Gold Mines

Jock McCulloch

South Africa’s gold mines have always been dangerous. In addition to traumatic injuries, they have particularly high rates of the dust-induced lung disease, silicosis. The Commission into Safety and Health in the Mining Industry of 1995 found that dust levels were hazardous and that they had probably been so since the 1940s.1 This conclusion is unsurprising given the high silica content of the host ore, the depth of the mines, their reliance upon migrant labour and the racialised work regimes that characterised most of their history. Recent research puts the silicosis rate in living miners at between 22 and 30 per cent.2 Jill Murray’s postmortem data estimates that up to 60 per cent of miners will eventually develop what is a life-threatening and untreatable disease.3

The mines have also played a role in the spread of tuberculosis, a well-known consequence of exposure to silica dust. The incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa is currently among the highest in the world, with the infection rate among gold miners being ten times higher than for the general population.4 The majority of miners are migrant workers, which has resulted in the transmission of disease to rural communities and across national borders.5 There is strong evidence, stretching back to the 1920s, that South Africa’s mines have spread tuberculosis to neighbouring states.6

The fact that miners with lung disease have not been able to gain compensation lies behind the litigation currently before courts in Johannesburg and London. The cases against Anglo American, Gold Fields and Harmony, which are now into their tenth year, may eventually involve hundreds and thousands of miners and their surviving families.7 One British financial analyst has put the potential payout at $US100 billion, making it the largest class action of its kind.8

In light of the current litigation, it is surprising that for most of the twentieth century South Africa’s gold mines were believed to lead the world in the prevention of silicosis or miners’ phthisis, the oldest and most intractable of the occupational diseases. The major reason was the data presented in the annual reports of the Miners’ Phthisis Medical Bureau (the Bureau), the body responsible for awarding compensation and for collating the official data. In the period 1917 to 1920, for example, the silicosis rate among white miners was stated to be 2.195 per cent.9 By 1935, it had fallen to 0.885 per cent. The rate for black miners was even lower. For 1926 to 1927, it was recorded as 0.129 per cent and for 1934 to 1935, it had fallen to 0.122 per cent.10 In the period 1946 to 1947, the silicosis rate among black miners was 0.178 per cent, perhaps the lowest incidence among hard-rock miners anywhere.11 The Bureau’s explanation for the variation in the silicosis rate between black and white miners was migratory labour, which supposedly protected men on contracts from continuous dust exposure and thus from injury.12 The data was accepted as authoritative by the departments of Mines and Health and the achievements of the Rand mines featured prominently in science and policy debates in Australia, France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. By 1930, South Africa’s gold mines were presumed to be a model of safety. What the admirers of the Rand mines did not realise is that the official disease rates were based on the number of compensation awards for injury, rather than the actual injury rates. Since mine medical officers controlled referrals of black miners to the Bureau, which alone had the power to make awards, they also controlled the production of the most important data.

A second factor that made the figures unreliable was the migrant labour system. The official data recorded the number of men who became ill or died at the mines. But there was always a gap between this figure and the actual morbidity and mortality rates. The deaths of men killed in accidents were recorded, as were those who died in the compounds from infectious diseases such as pneumonia, meningitis or enteric fever. Silicosis and tuberculosis could take years to kill and those deaths usually occurred in the rural areas, out of sight. In addition, the industry used the repatriation of sick and dying men to minimise the cost of compensation. This strategy lowered the official disease rates even further. In making policy, both the South African state and the imperial authorities in London relied upon these artificial figures.13

The repatriation system was brutal. Each Tuesday morning, two trains (with special coaches for lying-down cases) left Booysens Station in Johannesburg, one for Ressano Garcia in Mozambique, the other for the Cape, carrying repatriated miners. The trains had a white conductor to look after the patients, but no medical officer. In addition to ‘ordinary repatriations’ of miners with traumatic injuries, roughly 20 men suffering from tuberculosis were shipped out each week. Many were seriously ill and desperate to return to their families. The Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (Wenela) was also keen for their departure, as their presence added to overcrowding at the hospital. In February 1925, Dr Girdwood, the chief medical officer with Wenela, responded in an internal memo to criticism in the press that the trains arriving at Ressano Garcia were full of corpses:

If one considers the pathology of the lungs in these cases, large, ragged, breaking-down cavities full of pus, which might at any moment ulcerate through the blood vessel and cause a fatal haemorrhage, it should not be a matter of surprise that cases do die in the train, but that so few do.14

South Africa’s transition to majority rule in 1994 coincided with a recognition of the high incidence of silicosis among miners. Today these rates are a hundred times greater than the official data during most of the twentieth century. Rather than any recent dramatic increase in silicosis and tuberculosis, the discrepancy between the past and current data is due to a systematic under-reporting of cases, stretching back almost a century. This under-reporting became visible only with political transformation.

The mines

The Rand mines are the largest and deepest in the world and historically they have been among the most profitable. The mines employed a huge number of migrant workers drawn from rural communities and between 1911 and 1990 approximately 50 per cent of recruits were from neighbouring states. Such recruits were attractive to employers because they would accept lower wages than their South African counterparts. In addition, if the gold industry had drawn its workforce from local communities, the towns and villages surrounding the mines would soon have filled with men crippled by occupational lung disease. This, in turn, would have increased the political pressures to reduce the risks.

The High Commission Territories of Bechuanaland (Botswana), Swaziland and Lesotho, which were major supplies of labour, had no X-ray facilities and no specialists to identify the disease burden among returning miners. In addition, colonial administrations were dependent upon the capitation fees the Chamber of Mines’ recruiting arm (Wenela) paid for each recruit. They also depended upon the mines to assist in collecting outstanding hut tax.

The South African mining industry has always been politically powerful and dominated by a handful of corporations. For long periods, the mines were South Africa’s most important employer, the major earner of foreign exchange and the major source of government revenue. This, in turn, shaped the relationship between capital, labour and the state. On the international stage, the industry was just as dominant. By 1923, the Rand mines were producing more than 50 per cent of the gold on which the financial stability of Western economies depended.

The mines were places of constant change. Over time, they became bigger, they went deeper and the technologies used to extract ore and reduce the dust levels were improved. There were also changes in the conditions in compounds and in the provision of medical care. What did not change was the industry’s dependence on the cheap labour provided by oscillating migration.

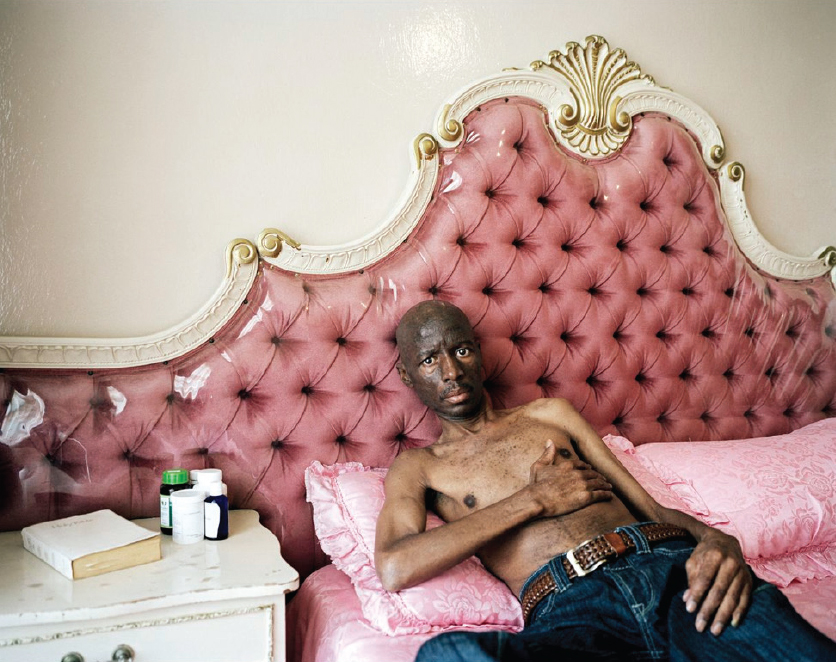

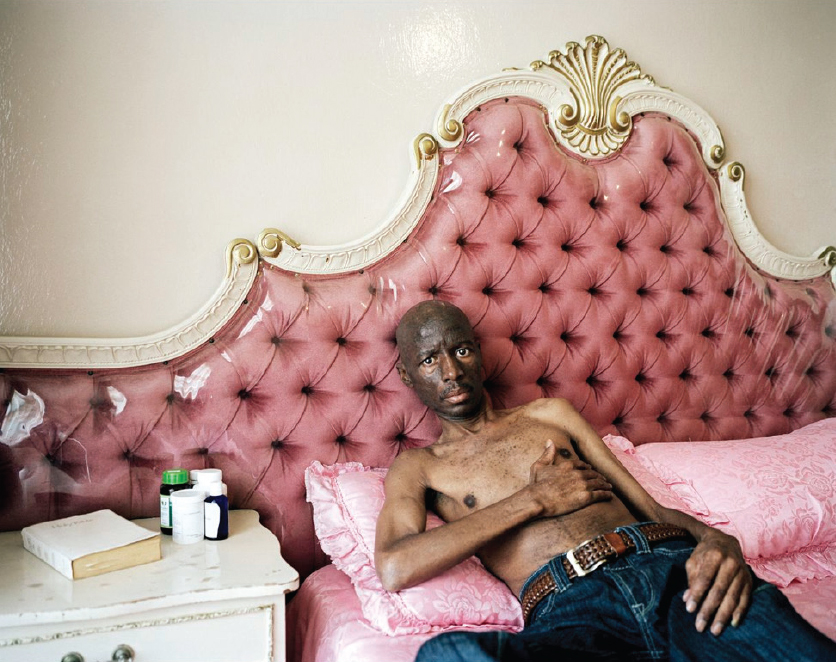

Figure 7.1

Ilan Godfrey

Mahloma William Melato, silicosis victim, Oppenheimer Park, Tabong, Welkom, Free State

2012

C-print

100 × 125 cm

Collection of the artist

The workforce consisted of a unionised white labour aristocracy employed in supervisory roles and black migrants who did the bulk of the manual work. In 1910, there were 120 000 black miners and 10 000 whites; by 1929, black miners numbered 193 221 while there were 21 949 whites.15 The workforce peaked at more than half a million in the late 1970s and has since declined sharply. In 2012, it had fallen to slightly more than 14 000.

Over the past 30 years, the industry has been through a number of structural changes, beginning with the establishment of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1982. The NUM’s emergence at a time of a falling gold price and massive retrenchments forced the union to focus upon job security, rather than occupational health.

Under minority rule, every aspect of mine work was racialised. White miners were designated as skilled and black miners (native labourers) as unskilled. They did different jobs for different rates of pay and for different contract periods. White and black workers were employed under different compensation regimes, they were subject to different forms of medical surveillance and they received different medical care: there were sanatoriums for white silicotics, but repatriation for black miners.

The fixed price of gold meant that the mining houses did not compete against each other for a share of a finite market, but were able to pursue an agreed set of policies through the Chamber of Mines. In addition to preventing competition among producers, gold pricing made production costs even more important than in other industries. A rise in working costs, such as stores or wages, could not be passed on to consumers. As a result, where possible, wage increases were resisted. Employers were so successful that, as Francis Wilson has shown, the wages of black miners did not rise between 1910 and 1970.16 In addition to wages, expenditure on compounds to house migrant workers, occupational health and compensation were areas in which costs could be minimised.

Medical surveillance

South Africa’s gold mines were the first in the world to compensate silicosis (1912) and tuberculosis (1916) as occupational disease. The provision of awards was based on a system of medical surveillance, which began with the Miners’ Phthisis Act of 1911 and was extended by the subsequent Acts of 1912, 1916 and 1925. Surveillance consisted of pre-employment and periodic examinations. The Acts also required that men who had served their contracts, usually of between six months and a year, were to be given a medical before they left the mines.

On their arrival in Johannesburg, recruits were examined prior to being assigned to individual mines.17 There was a massive flow of labour through the system and mine medical officers were expected to process recruits as quickly as possible. In 1913, each of the 39 part-time officers was responsible for around 3 000 miners and more than 100 hospital patients, many of whom had suffered traumatic injury.18 Not surprisingly, the examinations at the Wenela compound in Johannesburg were cursory and occasionally resulted in men who were seriously ill being sent underground. It was common for men with infective tuberculosis to die while still working.19 Records were not kept, which meant that when migrant workers returned to Johannesburg, as most did to serve a further contract, they had no medical history.20

The periodic examinations of serving miners focused on weight loss as a marker for lung disease. Men who had lost five pounds or more between two weighings, or six pounds over three consecutive weighings, were given a more detailed examination.21 The process was more a parade than a medical examination and in 1927 Dr Watkins-Pitchford, chair of the Bureau, admitted that at best it identified half of the silicosis and tuberculosis cases.22

The conduct of medicals changed little over time and the examinations carried out in the 1950s were much the same as they had been 30 years earlier. In his memoirs Dr Oluf Martiny, who served as a medical officer with Wenela from 1954 until 1980, describes how on a particularly busy morning he and six colleagues examined 12 000 recruits.23 The rationales for entry and exit medicals were also stable.24 Under the Miners’ Phthisis Acts, the entry medicals were to protect employers from hiring men with existing diseases. The exit examinations were to protect the interests of labour by identifying those men entitled to compensation. In each instance, employers (who had an interest in minimising the number of awards) controlled the medicals. The miners’ phthisis or silicosis commissions, held between 1919 and 1952, were often critical of the medical system and of the obstacles black miners faced in applying for compensation. The Commission of 1919 pointed out that death certificates often cited ‘general tuberculosis’ as the cause of death when a miner had died from pulmonary tuberculosis. The Commission also found that the periodic medical examinations were inadequate and often there was no exit exam as required under the Act. This was so even in cases of seriously ill men who had spent months in hospital.25 The findings of the 1919 Commission were endorsed by the Young (1930), Stratford (1943), Allan (1950) and Beyers (1952) commissions.26 One of the themes in those reports was the failure of employers to carry out adequate exit medicals. Those findings are consistent with the research carried out since 1994. Among Jaine Roberts cohort of 205 former miners from the Eastern Cape, 85.3 per cent had not received an exit examination.27 As a result, men with silicosis and tuberculosis are still being denied compensation.

Tuberculosis and HIV and AIDS

The steady decline in the official tuberculosis rate between 1960 and 1968 was followed by a sharp rise from the mid-1970s. Industry-wide rates then doubled between 1976 and 1979. In 1992, the Chamber of Mines reported that the overall incidence was around 16 per 1 000, an official level not seen since the 1920s.28 Since then the rates have risen inexorably from 806 per 100 000 in 1991, to 1 914 per 100 000 in 1998, to 3 821 per 100 000 in 2004.29 Mine medical authorities have attributed the rise to the increasing background rates in the areas from which the mines draw their labour. In addition, there has been better case detection, an ageing workforce and the arrival of HIV and AIDS.

One of the major reasons for the rise in the rates of infection has been the policy known as reactivation, which has seen miners with tuberculosis permitted to continue to work underground while receiving treatment. This innovation, which was adopted industry wide by 1983, without any apparent change to the existing legislation, flies in the face of a 100-year-old medical orthodoxy. This orthodoxy, which has never been challenged, holds that continued dust exposure is lethal for workers with tuberculosis.30 The result has driven up the infection and mortality rates in the same way that stabilisation has increased the rates of silicosis.31

The South African gold mines, with their migrant populations and single-sex hostels, have been the ideal environment for spreading sexually transmitted diseases. The 1990s saw a dramatic increase in HIV and AIDS prevalence. In 1987, 0.03 per cent of mineworkers from areas other than Malawi tested HIV-positive. This increased to 1.3 per cent in 1990, rising to 24 per cent in 1999 and reaching 27 per cent in 2000.32 HIV and AIDS infection greatly increases the incidence of tuberculosis. By 1999, 80 per cent of tuberculosis patients on the mines were HIV-positive.33 The combination of HIV and AIDS and silicosis further enhances the tuberculosis risk. With the advent of HIV and AIDS, multi-drugresistant forms of tuberculosis began to appear. Other industries that rely on migrant labour, such as the transport sector, also have high burdens of disease. Public health services in labour-sending areas within South Africa and in neighbouring states are unable to effectively treat returning migrant workers. As with a number of pathologies arising from the mines, the incidence of HIV and AIDS has an underlying source: the breakdown of families under the weight of oscillating migration.

Bureau medicine and post-mortems

It is tempting to assume that the industry’s failures to provide adequate medical examinations and compensation, like the attendant failures of the regulatory authorities to supervise the industry, have been due to inefficiencies or a lack of resources. There is evidence that, on the contrary, these failings were the result of a deliberate policy.

We have a first-hand account of the Bureau’s methods in assessing compensation claims from Dr GWH Schepers, who served as an intern for more than eight years. Schepers graduated in medicine from the University of the Witwatersrand in 1938. In 1944, he was assigned to the Bureau where he remained until he emigrated to the United States in 1954. Schepers was a whistle-blower and after his protest against the Bureau’s treatment of miners, his South African career came to an abrupt end.34

Schepers found the Bureau doctors ‘careless and unfeeling’ in their treatment of the white miners who went for medical assessment. He was astonished at the way medical reviews of black miners were conducted at the Wenela compound.35 The miners were lined up naked and a doctor would run a stethoscope over each chest, doing ten men in a minute. The other test was weight loss, a notoriously unreliable marker for lung disease. The X-ray equipment was adequate, but there was a massive volume of work. The Wenela doctors read the X-rays and a small number of men, who in Schepers’s words ‘were usually in the process of dying’, were set aside for review. Schepers discovered there was a lot of disease and that in many cases the miners ‘had simply been worked to death’. The dust levels were such that after two years underground, a man’s health was often ruined: ‘Whites survived on average three years after retirement. Blacks who had worked three consecutive contracts were usually dead a year after they left the mines.’ The rate of tuberculosis was very high, but in most cases infected miners were repatriated without compensation. What Schepers described as ‘an horrendous spread of tuberculosis from the mines’ was common knowledge at the Bureau.

There is also a body of official data that supports Schepers’s testimony. Under the Miners’ Phthisis Consolidation Act of 1925, any miner who died suddenly was subject to a post-mortem. Between 1925 and 1950, the results were published in the Bureau’s annual reports. During this period, on average more than 500 miners would perish each year in accidents and presumably many of the autopsies were performed on that random group. The Bureau data shows far higher rates of silicosis and tuberculosis than were identified in living miners. This in itself is not surprising, as it had long been acknowledged that post-mortems might uncover lung disease that had been missed at a clinical examination. What is surprising is the dramatic difference between the two sets of figures.

The data sequence from 1924 until 1950 reveals a tide of disease. In 1924, the lungs of 122 white and 176 black miners were examined. Silicotic changes were found in 97 or 79.5 per cent of whites. Among this group, 28 had been certified as free of silicosis, some within months of death. The lungs of the 176 black miners showed an even higher rate: in 78 the cause of death was tuberculosis, even though the deceased were subject to periodic medicals and had not been diagnosed while alive. In another 60 cases, tuberculosis with or without silicosis was present.36 In 1928, the lungs of 227 white and 429 black miners were examined. Of the white miners, 55 per cent had lung disease, while 81 per cent of black miners were affected.37

In 1941, post-mortems were performed on 999 black miners. Of this cohort, only 162 were free of silicosis or tuberculosis. In total, 170 had both diseases, while 606 had tuberculosis alone. At death, 84 per cent of the cohort had a compensatable disease.38 The context for this data is also significant. Between 1931 and 1941, there was a sharp increase in the number of black miners. Consequently, many of the deceased who appear in the 1941 report were probably new to the industry. Of the 911 examined in 1949, 327 were Europeans and 584 were ‘native labourers’. Of the European miners, 43 per cent had some form of disease, a marked increase that coincided with the war years.39 Of the black miners, 83 per cent were suffering from silicosis and/or tuberculosis.40 In the following year, of the 649 blacks examined, 370 or 55 per cent had tuberculosis without silicosis and the total disease rate was 82 per cent.41 The Bureau’s annual reports offer no comment on the results. After 1950, the Bureau ceased publishing post-mortem data.42

The results from 1924 to 1950 are consistent with the science produced since majority rule. They suggest that the exit medicals were inadequate, the compensation system was flawed and that tuberculosis was being exported to rural areas. The post-mortem data was known to the research community in Johannesburg and to senior officers in the departments of Mines, Native Affairs and Health, as well as the Chamber of Mines. The data was also available to members of parliament, but nothing was done.

Conclusion

The Bureau’s post-mortem data suggests that sometime after 1925, the industry recognised that it was impossible to engineer dust out of the mines and therefore impossible to prevent silicosis and tuberculosis. This, in turn, confronted Anglo American and its competitors with a choice: they could either close the mines or not compensate most of those men who developed lung disease. The latter choice was made easier by the political alignments of minority rule. A racialised state was dependent upon the income generated by the country’s most important employer and earner of foreign exchange. The outsourcing of medical surveillance gave employers control over the official data and thereby the power to make the mines safe, if only on paper.

It is worth reflecting upon the consequences if the Bureau’s autopsy data, rather than the number of compensation awards, had been used to measure the disease rate. Such an approach would have demolished the myth of safe mines promoted by the Chamber of Mines and it may well have encouraged both the British government and the International Labour Organization to review their support of Wenela’s recruitment in the tropical north. Acknowledgement of a high disease rate would have shifted the research agenda and perhaps forced the South African Institute for Medical Research (SAIMR) to conduct follow-up studies of silicosis and tuberculosis in labour-sending areas, studies that had to wait until after 1994. Finally, such a reversal may have alerted trade unions and governments in the United Kingdom, the United States and elsewhere to the dangers of exposure to silica dust.

The failure of the South African system of medical surveillance and compensation is not unique. As the histories of British coal mining and asbestos manufacture suggest, resistance by management and the failures of regulatory authorities often result in a gap between legislative intent and what happens in the workplace.43 The story of silicosis on the Rand is, however, different. Under minority rule the failures by the Bureau, the SAIMR and the Department of Mines were so systemic in character, so massive in scale and of such financial benefit to industry that they are suggestive of a coherent policy. Legal discovery flowing from the current litigation may show that to be the case. Until then, we can be sure that the failures of the South African system underpinned the commercial success of the nation’s most important industry and allowed significant costs of production to be shifted onto rural communities both within and outside South Africa’s borders.

Notes

1. See Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Safety and Health in the Mining Industry (Pretoria: Department of Minerals and Energy Affairs, 1995), 51–53.

2. See TW Steen, KM Gyi, NW White, T Gabosianelwe, S Ludick, GN Mazonde, N Mabongo, M Ncube, N Monare, R Ehrlich and G Schierhout, ‘Prevalence of Occupational Lung Diseases Among Botswana Men Formerly Employed in the South African Mining Industry’, Occupational and Environmental Medicine 54 (1997), 19–26 and J Murray, T Davies and D Rees, ‘Occupational Lung Disease in the South African Mining Industry: Research and Policy Implementation’, Journal of Public Health Reports 32 (2011), 65–79.

3. J Murray, ‘Development of Radiological and Autopsy Silicosis in a Cohort of Gold Miners Followed up into Retirement’, paper presented at the Research Forum, National Institute for Occupational Health, Johannesburg, 26 May 2005.

4. D Stuckler, S Basu, M McKee and M Lurie, ‘Mining and Risk of Tuberculosis in Sub-Saharan Africa’, American Journal of Public Health 101.3 (2010), 524.

5. Approximately 40 per cent of the adult male tuberculosis patients in Lesotho’s hospitals work or have worked in South African mines. AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa, The Mining Sector: Tuberculosis and Migrant Labour in Southern Africa (July 2008), 2.

6. See Stuckler et al., ‘Mining’, 529 and J McCulloch, South Africa’s Gold Mines and the Politics of Silicosis (Oxford: James Currey, 2012), 85–105.

7. See Mankayi Mbini and Anglo American Corporation of South Africa Ltd., High Court of South Africa (Witwatersrand Local Division), Case No. 04/18272, 2 August 2004 and J McCulloch, ‘Counting the Cost: Gold Mining and Occupational Disease in Contemporary South Africa’, African Affairs 108.431 (2009), 221–240.

8. See M Cohen and C Lourens, ‘Blowback from the Apartheid Era’, Bloomberg Businessweek, 6 June–12 July 2011; see also A Trapido, ‘An Analysis of the Burden of Occupational Lung Disease in a Random Sample of Former Gold Mineworkers in the Libode District of the Eastern Cape’, PhD dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2000, 196–202.

9. See Table 1: Incidence of Silicosis and Tuberculosis in The Prevention of Silicosis on the Mines of the Witwatersrand (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1937), 236.

10. See Table 1: Incidence of Silicosis and Tuberculosis’ in The Prevention of Silicosis, 242.

11. Report of the Silicosis Medical Bureau for the Year ended 31st March 1949 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1950), 6–7.

12. As long ago as 1960, Jack Simons described the industry’s claims that the migrant labour system saved miners from silicosis as ‘a dangerous illusion’. He was sure that the true incidence of occupational disease was being hidden by industry and the state; see HJ Simons, ‘Migratory Labour, Migratory Microbes: Occupational Health in the South African Mining Industry; The Formative Years, 1870–1956’ unpublished manuscript, 1960, 34.

13. McCulloch, South Africa’s Gold Mines, 91–98.

14. Letter from AI Girdwood, Chief Medical Officer, to General Manager WNLA [Wenela], Johannesburg, 17 February 1925, Diseases and Epidemics, Tuberculosis, February 1923 to December 1930, WNLA 20L, The Employment Bureau of Africa (Teba) Archives, University of Johannesburg.

15. See Table 5: Employment on the Gold Mines in D Yudelman, The Emergence of Modern South Africa: State, Capital, and the Incorporation of Organized Labor on the South African Gold Fields, 1902–1939 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983), 191.

16. In fact, black wages were probably lower in 1969 than they had been in 1911; see F Wilson, Labour in the South African Gold Mines 1911–1969 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972), 46.

17. See B Penrose, ‘Medical Monitoring and Silicosis in Metal Miners: 1910–1940’, Labour History Review 9.3 (December 2004), 285–303.

18. See Annexure 6: ‘Whole-Time Medical Officers’ in Report of the Native Grievances Inquiry, 1913–1914 (Cape Town: Government Printer, 1914), 102.

19. See, for example, the mortality data published in the annual Report of the Miners’ Phthisis Medical Bureau in the period from 1925 until 1950.

20. EH Cluver, ‘The Progress and Present Status of Industrial Hygiene in the Union of South Africa’, Journal of Industrial Hygiene 11.6 (June 1929), 204.

21. ‘Miners’ Phthisis Act No. 35 (1925): Condensed Précis of Regulations and Procedure (Natives and Non-Europeans) for Mine Medical Officers’, Proceedings of the Transvaal Mine Medical Officers’ Association 6.4 (October 1924), 4.

22. W Watkins-Pitchford, ‘The Silicosis of the South African Gold Mines’, Journal of Industrial Hygiene 9.4 (1927), 111.

23. O Martiny, ‘My Medical Career’, unpublished manuscript, Johannesburg, November 1995 to September 1999, 4–10.

24. See Dr WG McDavid, ‘This Is the Mine Medical Officer’s Daily Round’, in Doctors of the Mines: A History of the Work of Mine Medical Officers, ed. AP Cartwright (Cape Town: Purnell and Sons, 1971), 90–94.

25. Report of the Commissions of Inquiry into the Working of the Miners’ Phthisis Acts (Cape Town: Government Printer, 1919), 11–12.

26. The commissions after 1952 were notable for their uncritical support of the industry. Without exception, they found that with regard to occupational disease, the gold mines were among the safest in the world. See, for example, Report of the Commission of Enquiry Regarding Pneumoconiosis Compensation (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1964) and Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Compensation for Occupational Diseases in the Republic of South Africa (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1981).

27. J Roberts, The Hidden Epidemic Amongst Former Miners: Silicosis, Tuberculosis and the Occupational Diseases in Mines and Works Act in the Eastern Cape, South Africa (Durban: Health Systems Trust, June 2009), 81.

28. RM Packard and D Coetzee, ‘White Plague, Black Labour Revisited: Tuberculosis and the Mining Industry’, in Crossing Boundaries: Mine Migrancy in a Democratic South Africa, eds. J Crush and J Wilmot (Cape Town: Institute for Democracy in South Africa, 1995), 109.

29. D Rees, J Murray, G Nelson and P Sonnenberg, ‘Oscillating Migration and the Epidemics of Silicosis, Tuberculosis, and HIV Infection in South African Gold Miners’, American Journal of Industrial Medicine 53.4 (2010), 398–404.

30. See McCulloch, South Africa’s Gold Mines, 139–154.

31. See Rees et al., ‘Oscillating Migration’, 400–401.

32. Ibid., 401.

33. Interview with Dr Oluf Martiny, Forest Town, Johannesburg, 27 April 2011.

34. See J McCulloch, ‘Hiding a Pandemic: Dr GWH Schepers and the Politics of Silicosis in South Africa’, Journal of Southern African Studies 35.4 (2009), 835–848.

35. This account of the Bureau’s methods comes from a series of interviews I conducted with Dr Gerrit Schepers at his home in Virginia in the United States in 2010. Gerrit Schepers died in September 2011 at the age of 97 (interviews with Dr Gerrit Schepers, Great Falls, Virginia, 23–28 October 2010).

36. Report of the Miners’ Phthisis Medical Bureau for the Twelve Months Ending July 31, 1924 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1925), 4.

37. Report of the Miners’ Phthisis Medical Bureau for the Year Ended the 31st of July, 1928 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1929), 7.

38. Report Miner’s Phthisis Medical Bureau for the Three Years Ending 31st July 1941 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1944), 7.

39. Report of the Silicosis Medical Bureau for the Year Ended 31st March 1949 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1950), 6.

40. Report of the Silicosis Medical Bureau for 1949, 8.

41. Report of the Silicosis Medical Bureau for the Year Ending 31st March, 1950 (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1951), 8.

42. See Report of the Silicosis Medical Bureau for the Two Years Ended 31 March, 1952, and 31 March 1953. (Pretoria: Government Printer, 1955).

43. See A McIvor and R Johnston, Miners’ Lung: A History of Dust Diseases in British Coal Mining (London: Ashgate, 2007) and G Tweedale, Magic Mineral to Killer Dust: Turner & Newall and the Asbestos Hazard (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).