CHAPTER 8

‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africa’s ‘Labour Empire’

Fiona Rankin-Smith, Peter Delius and Laura Phillips

Days before the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation in Beijing in July 2012, the Mail & Guardian carried a story about a ‘new form of colonialism’. Warning readers about labour law violations and the exploitation of Africa’s resources, author Paula Akugizibwe noted: ‘The boom of China in Africa is proving to be one of the most striking developments of twenty-first-century geopolitics’.1 But what the article did not say – and what has been largely forgotten in the South African imagination – is that there were equally dramatic headlines about the Chinese in South Africa slightly more than 100 years before. In the first years of the twentieth century, however, they signalled the geopolitics of an expanding British-South Africa ‘labour empire,’ as the SS Tweeddale docked at Port Natal (Durban) in July 1904, with a shipload of contracted Chinese labourers destined for the gold mines of the Transvaal.2

The sudden influx of Chinese labour in 1904 was the beginning of a six-year ‘experiment’ in saving the white mining industry’s cheap labour economy. As low-wage black labour from South Africa and Portuguese East Africa became less reliable and gold production levels dropped, mine-owners looked to China, where drought, floods and the Boxer Rebellion had driven unemployment rates to unprecedented levels.3 With the new Milner government’s support for the mining industry, the Chamber of Mines capitalised on British networks and administration in China to set up a vast system to import Chinese labour.4

Chinese men who were successfully recruited arrived into a world that was racist, violent and exploitative. The very ordinance that legislated their recruitment outlined a range of restrictive employment conditions. These included preventing Chinese miners from leaving the compound without a permit and for more than 48 hours; the exclusion of Chinese labourers from all skilled work and an absolute restriction on trading or owning any property.5 While sources from the Chinese miners themselves are quite limited, it is clear from the records of the Chamber of Mines that the conditions of employment were unbearable for many.

Gary Kynoch quotes figures from the first four years of the Chinese mining presence, showing that there were ‘145 murders, 124 suicides, 28 state executions, 17 killed during the commission of “outrages” – crimes committed off mine premises – and 268 deaths directly related to opium use’.6 Alienated by their inability to speak English, separated from their destitute families in China and forced into submission by Chinese policemen, miners regularly tried to desert their employment.7

On the mines and in the compounds, however, many Chinese migrant groups formed hierarchies and factions, often based on gambling conflicts and criminal networks that operated both on and off the mines. There was also a lot of unrest and opposition to working conditions, the most significant being the 1905 go-slows and strikes. On 29 March 1905, a group of Chinese miners at North Randfontein Mine initiated a go-slow strike, refusing to drill more than 13 inches of rock per day, less than half of the average daily amount.8 Eventually, the managers on the mine agreed to raise the wages of the miners, but they also initiated the practice of ‘piece work’ for hammer-men, giving them a bonus for drilling more than 36 inches and thereby incentivising harder work and increasing production rates.

However, by 1907, there was pressure on the Transvaal government and mine-owners to repatriate the Chinese miners. This pressure came from a number of different quarters. Locally, white miners and traders had always felt uncomfortable with the Chinese presence on the mines because of the jobs they were perceived to be stealing and the money they were remitting out of the country. And with the British Liberal Party in power from 1906, the ‘Chinese Slavery’ campaign was reinvigorated to pressure capital to stop employing Chinese workers under ‘slave-like conditions’.9

The mines were now in a far better position than they had been three years previously. The shortage of cheap labour had been eased by the Chinese presence and it was now possible to peg African wages to the levels set for the Chinese miners. At the same time, the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (Wenela) had become more active and effective in recruiting cheap black labour for the mines.10 Once the last three-year labour contract expired in 1910, the final group of Chinese migrants were thus sent back home. In total, more than 63 000 men had been brought to work on the Transvaal gold mines and in six brief years, the ‘Chinese labour experiment’ was over.

Notes

1. P Akugizibwe, ‘The Rise of ChinAfrica’, Mail & Guardian, 17 July 2012.

2. J Crush, A Jeeves and D Yudelman, South Africa’s Labour Empire (Cape Town: David Philip, 1991); P Richardson, ‘The Recruiting of Chinese Indentured Labour’, Journal of African History 18.1 (1977), 86.

3. In 1901, Chinese nationalists rose to drive out Western influence from China, in what is now commonly referred to as the Boxer Rebellion. However, by August of that year, they were defeated by the ‘Eight-Nation Alliance’, which included Britain, France, the United States, Japan, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia and Germany.

4. P Richardson, Chinese Mine Labour in the Transvaal (London: Macmillan, 1982), 27.

5. KL Harris, ‘Not a Chinaman’, Historia 52.2 (November 2006), 184.

6. G Kynoch, ‘Your Petitioners Are in Mortal Terror: The Violent World of Chinese Mineworkers in South Africa, 1904–1910’, Journal of Southern African Studies 31.3 (2005), 535.

7. L Callinicos, Gold and Workers: Volume 1 (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1980), 67.

8. Ibid., 68.

9. Richardson, Chinese Mine Labour, 5.

10. Callinicos, Gold and Workers, 69.

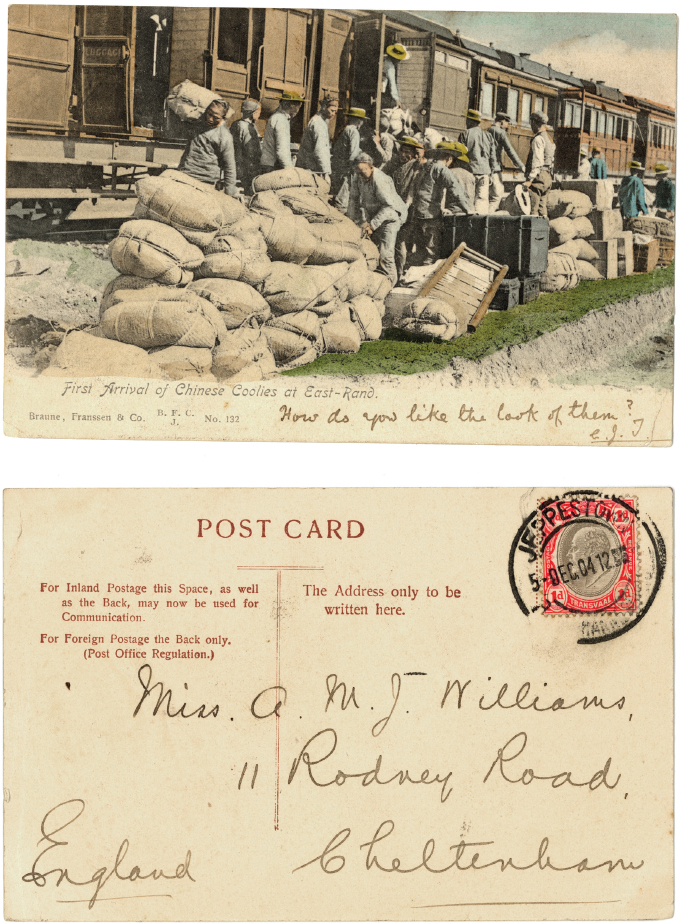

Figure 8.1

The caption reads ‘First Arrival of Chinese Coolies at East-Rand’. A handwritten note at the bottom reads: ‘How do you like the look of them?’

Photographer unrecorded

First arrival of Chinese coolies at East Rand

Postcard, Branne, Franssen & Co

1904

Collection of Warren Siebrits

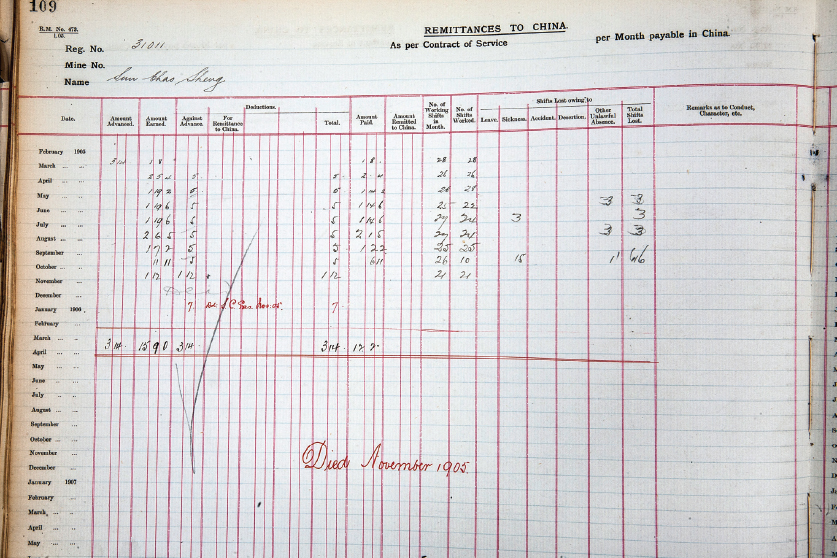

Figure 8.2

Chinese miners were housed in racially segregated compounds, though their compounds were of a higher quality than those of black miners

General plan of compound for Chinese labourers

Architectural drawing

1904

Collection of Warren Siebrits

Figure 8.3

Artist unrecorded

Postcard of Chinese compound

Date unrecorded

Historical Papers Research Archive, William Cullen Library, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

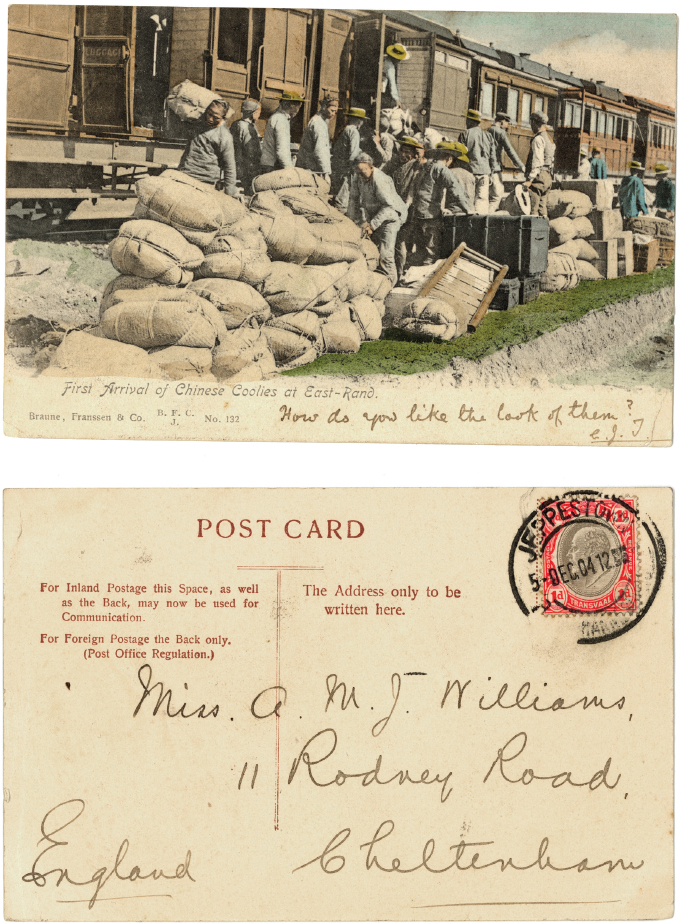

Figure 8.4

Photographer unrecorded

Performers of Chinese Opera on the Rand

Postcard, Hallis & Co

Date unrecorded

Historical Papers Research Archive, William Cullen Library, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

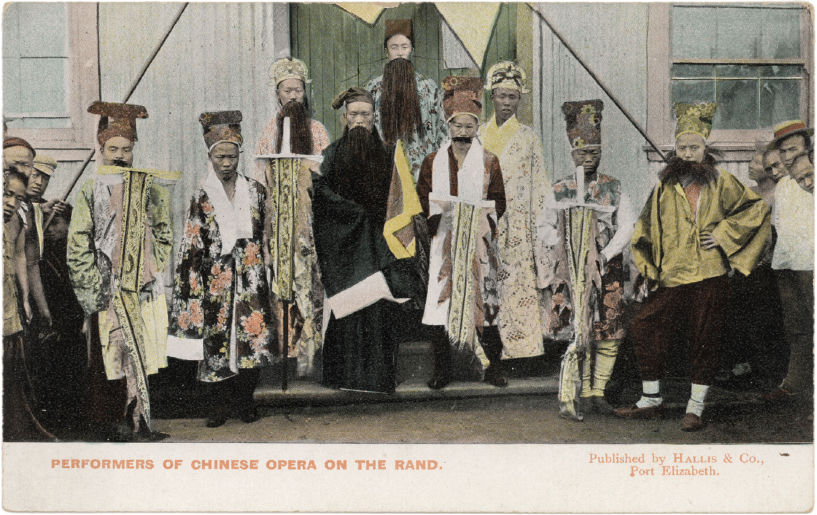

Figure 8.5

Remittances to China Ledger of Monthly Salaries for Chinese Workers

1905-1909

Collection of Warren Siebrits

Figure 8.6

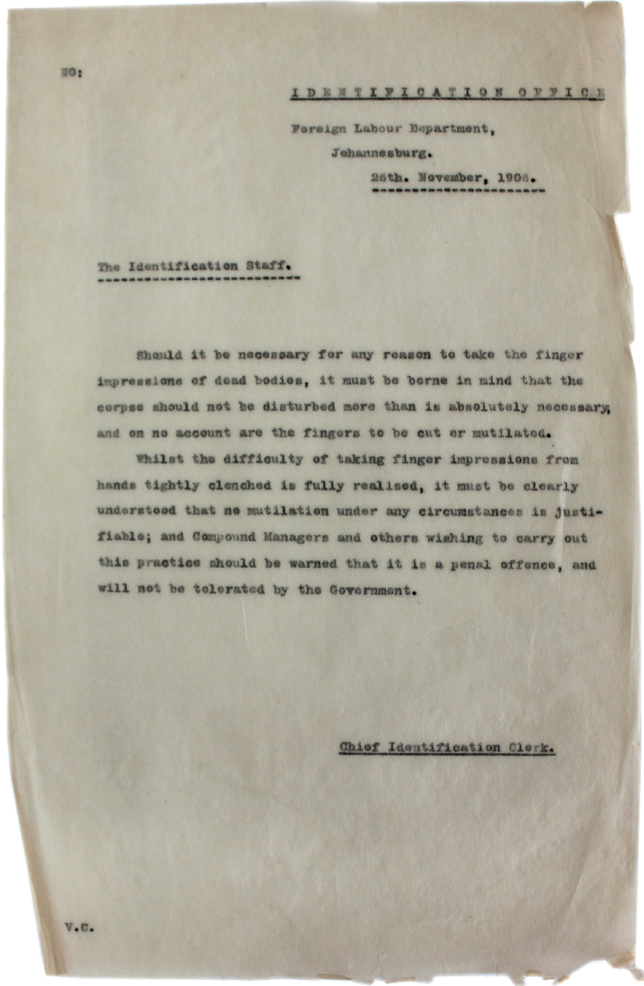

The letter reads: ‘Should it be necessary for any reason to take the finger impression of dead bodies, it must be borne in mind that the corpse should not be disturbed more than is absolutely necessary, and on no account are the fingers to be cut or mutilated. Whilst the difficulty of taking finger impressions from hands tightly clenched is fully realised, it must be clearly understood that no mutilation under any circumstances is justifiable; and Compound Managers and others wishing to carry out this practice should be warned that it is a penal offence, and will not be tolerated by the government.’

Fingerprint identification letter

Foreign Labour Department, 1906

Collection of Warren Siebrits

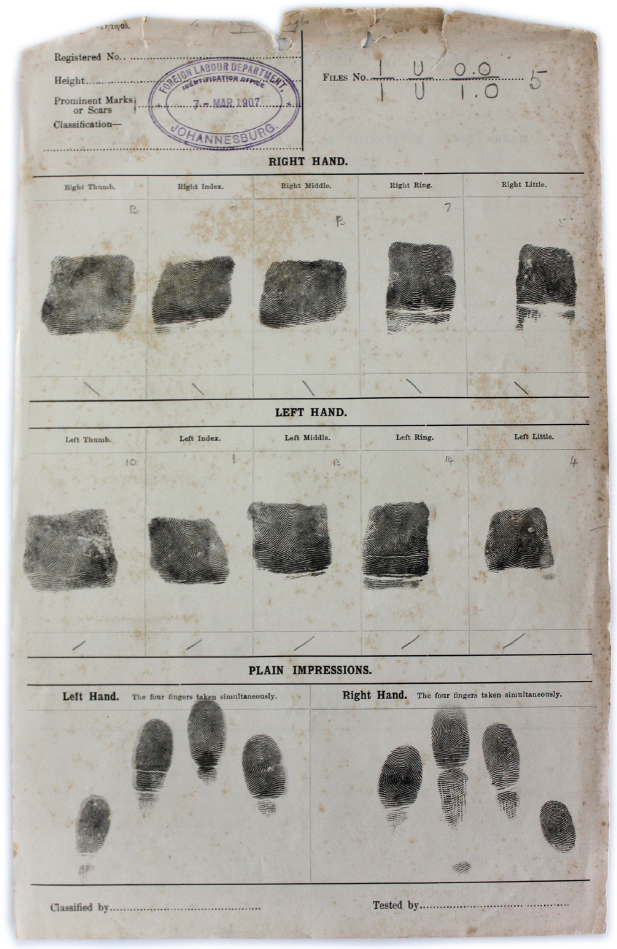

Figure 8.7

Form for identification of Chinese fingerprints

Foreign Labour Department, 1907

Collection of Warren Siebrits

Figure 8.8

Form for identification of Chinese fingerprints

Foreign Labour Department, 1907

Collection of Warren Siebrits

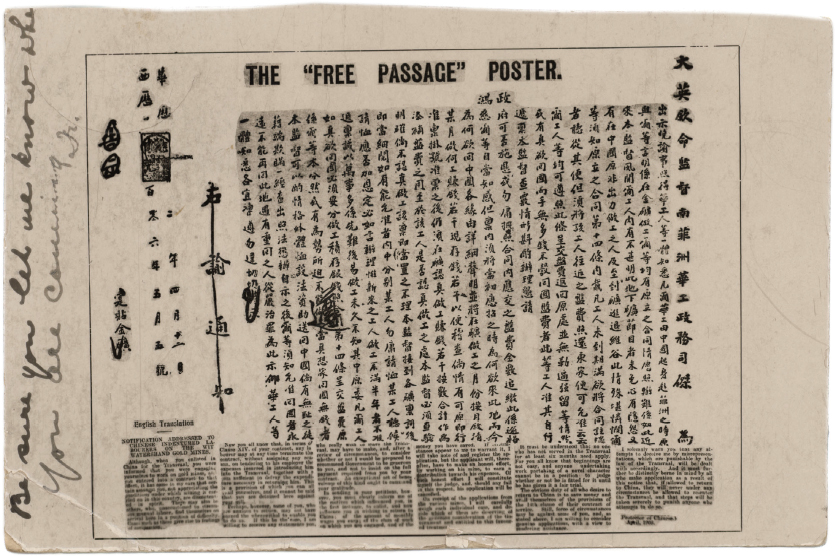

Figure 8.9

Many of the Chinese labourers found their time in South Africa unbearable. Not only were they far from their families in a hostile, alien environment, but also the working conditions were tough and they were earning very little. This poster notifies Chinese miners that they are free to break their contract, provided they can defray the costs of coming from and returning to China. In special circumstances, the poster says, the government will consider repatriating Chinese labourers even if they do not have sufficient funds to pay their employers.

The free passage poster

1906

Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

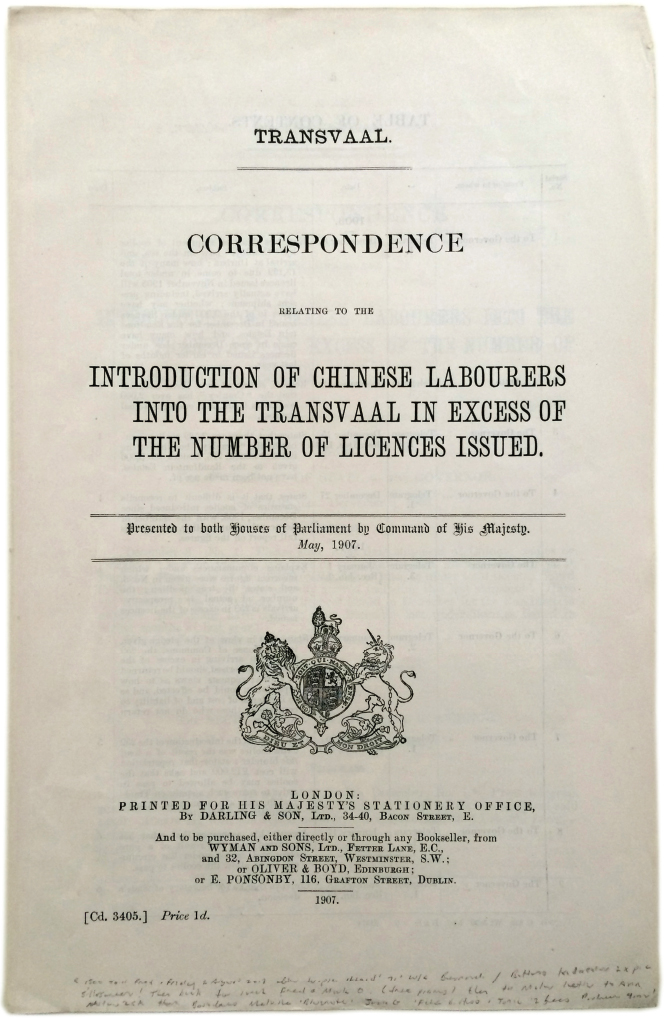

Figure 8.10

The ‘Chinese labour experiment’ caused a big stir in British politics. This is a report on the Chinese miners and systems of recruitment presented to parliament.

1907

Collection of Warren Siebrits

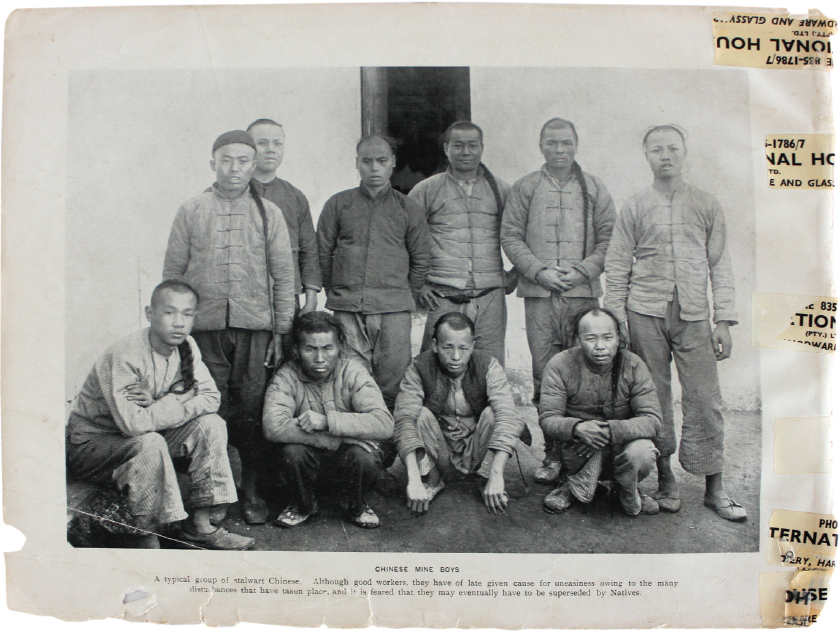

Figure 8.11

The caption below the image reads: ‘Chinese Mine Boys. A typical group of stalwart Chinese. Although good workers, they have of late given cause for uneasiness owing to the many disturbances that have taken place, and it is feared they may eventually have to be superseded by Natives.’

Torn page from unknown book

Collection of Warren Siebrits

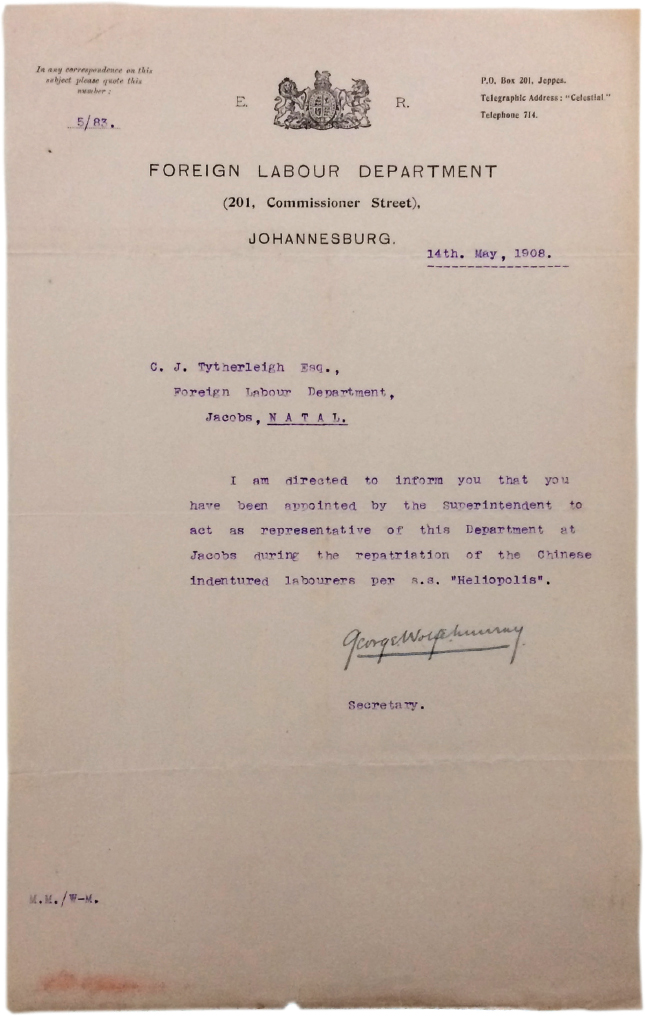

Figure 8.12

By the end of the first set of Chinese migrants’ contracts, a decision had been taken to halt their recruitment and repatriate those working in the Transvaal. The Foreign Labour Department oversaw both these processes. Here is a letter written on 14 May 1908 to CJ Tytherleigh Esq of the Foreign Labour Department, saying ‘I have been directed to inform you that you have been appointed by the Superintendent to act as representative of this Department at Jacobs during the repatriation of the Chinese indentured labourers per ss. “Heliopolis”.’

Foreign Labour Department, 1908

Collection of Warren Siebrits