Sometime in September 1920, an unnamed African from Mozambique was killed and his corpse eaten by hyenas inside the Sabi Game Reserve. According to the findings of a government investigation launched by CL Harries, the Sub-Native Commissioner for Sibasa, the African was part of a group of labour recruits travelling from a place called Mpafula on the Portuguese side of the border to Punda Maria, in the northern section of the reserve. The group, which included the man’s son, was led by Mafuta Sitoye and Longone Makuleke, ‘native runners’ for the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association. Popularly known as Wenela, the association was a labour recruitment agency founded in 1900 by the Chamber of Mines to help the mining industry meet its needs. The runners’ job was to accompany recruits from the Portuguese territory through the reserve to a pickup point in the northern section of the sanctuary, from where the workers would be sent by donkey wagons, trucks and trains to mines in the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. Every member of the September 1920 group, except the unnamed man, was a contracted recruit, meaning each had signed a contract to work on the mines for at least 18 months. The man had decided to travel with the group in order to visit friends on the South African side of the border. However, while the group was walking through the reserve, he fell ill. His son was ordered by the runners to stay and look after him. Father and son slept in the bush, but the next day, the runners came back and ordered the son to leave his father behind and proceed with them to Punda Maria, as he had contractual obligations to meet. The son duly left his father and moved on to Punda Maria. Meanwhile, the father was abandoned for ten days and ‘left to suffer and await death at the spot where he first took ill’.1 The two runners passed him often during those ten days as they ferried recruits back and forth through the reserve. In a letter to the magistrate of Louis Trichardt, dated 5 October 1920, Harries said:

This in itself is bad enough, but when one thinks of runner Mafuta passing by later with other gangs of recruits and making no attempt to get the suffering old man to some place where he could get shelter and attention, the matter leaves a very deplorable impression on one’s mind.2

Harries wanted the case investigated and action taken against ‘those who have acted in this inhumane manner’. He also wanted the magistrate to complain formally to Wenela in order to prevent a recurrence. His letter contained a sworn statement from a constable named Jim Shifango, who said that when he arrived at the scene of the man’s death on 2 October 1920, his corpse ‘was more than half-eaten by hyenas’. Shifango said the dead man was on his way to a place called Shikundu to visit friends and added: ‘It is a shame the way [the] deceased was left to die out in the wilds with no shelter of any sort over him and no one to look after him. At least his son might have been allowed to remain with him.’

The magistrate duly took up the matter with Wenela, but the association disputed the charges of neglect and inhumane conduct levelled at its runners. It produced a sworn statement by runner Sitoye, claiming that he gave the stricken man food and water and reported him to his ‘baas’. The magistrate, apparently finding Sitoye’s explanation unsatisfactory, again took the matter up with Wenela. When Wenela’s manager and secretary responded to the magistrate, he effectively blamed the dead man for bringing his fate upon himself:

A certain number of natives, some with friends amongst the contracted natives and others having no connection whatever with them, for protection and company join the parties of contracted natives proceeding in charge of the Association’s Conductors from the Portuguese border to Louis Trichardt. No advantage of any kind of course accrues to the Association through these stray boys [my emphasis] – rather the reverse but it is the Association’s policy to assist outside natives in such circumstances where it can conveniently do so.3

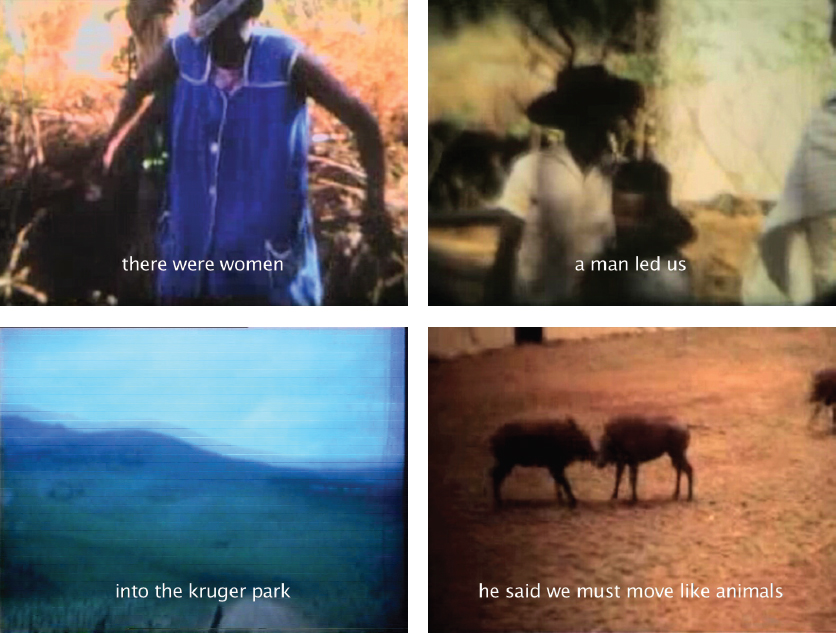

Figure 9.1

Penny Siopis

from PRAY

2007

Stills from digital video projection, 2 mins, 48 secs, sound

Collection of Penny Siopis, courtesy of Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

The secretary’s reference to ‘stray boys’, with its evocation of stray animals, is telling. It suggests that the dead man had been without an ‘owner’: domesticated perhaps, but under no one’s control. The secretary said one of the runners did in fact ask the recruits he was transporting to help him carry the stricken man to a place of safety, ‘but the boys in the gang refused, perhaps not unnaturally, to carry him’. He said they could have done more,

but it is, I am afraid, asking too much to expect natives, whether in the employ of the Association, or anyone else, to evince the same initiative and sense of humanity in such circumstances as would be expected from a European, and it is difficult to see in what way the Association can possibly give instructions to their native servants which will provide for every contingency.4

The secretary said while Wenela wished to assist so-called stray Africans passing through the reserve, it was not responsible for them. He suggested that, in future, ‘stray’ Africans who fell ill in the reserve be made the wards of the warden: ‘The responsibility of attending to the native will then lie with the Ranger as a Government official, and also as the representative of the Native Affairs Department.’

What this tragedy brings to light are various aspects of the park’s complex social history. The dead man’s fate highlights two facets of the relationship between Africans and the park: the matter of Africans for whom the park was, despite the inherent dangers, a zone of movement and the lives of the thousands of Africans for whom the park was a transit point between their homes and the mines in South Africa’s burgeoning cities. This chapter examines these aspects of the park’s social history, focusing in particular on the migrant labourers.

The dead man was a ‘stray’ because he had no ‘baas’. He did not fit into any of the categories that would have been immediately understood by park officials and those in Wenela’s head office in Johannesburg. He was neither a poacher nor a labourer. But he was clearly not the only one to see the park as a zone of movement. Reserve warden James Stevenson-Hamilton observed in a report in 1903: ‘There is a good deal of native traffic between the Crocodile and Sabi [rivers], Natives going from working in Komati Poort and Barberton chiefly, or people on the Crocodile [River] visiting their friends north of the Sabi or at Kraals under the Drakensberg, and vice versa.’5

The Africans Stevenson-Hamilton saw moving through the reserve were part of a historical network of flows and paths stretching over great distances. The reserve straddled one of the most significant corridors for southern Africa’s migrant labour system. About 360 kilometres in length and 60 kilometres at its widest, it covered a long narrow strip in the north-eastern corner of South Africa, with Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) to the north and Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) to the east. Through this corridor moved animals and people, especially migrant labourers. The migrant labour system had been in place since the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in 1868, with Mozambique proving to be one of the most fertile recruiting grounds for the mining industry. Young men from Mozambique’s southern provinces came to South Africa in droves to work on the diamond, gold and coal mines of South Africa. Historian Patrick Harries says the popularity of migrant labour in southern Mozambique was connected to political warring within the Gaza kingdom, ecological crises, generational and gender disputes over resources and the resultant need by young men to earn money independently of the senior men who held chiefly and political authority.6 These migrants were pioneers of southern Africa’s industrial working class.

Working in the mines offered these migrants a chance to start their own families and to free themselves from the clutches of their fathers and uncles, who controlled such resources as the cattle needed to pay the bride-wealth necessary to get married. Another important factor behind the men’s migrancy to the mines in South Africa was, as Peter Alexander says, ‘the desire to avoid xibalo (forced labour for the Portuguese), which, in common with wage labour in Lourenço Marques and elsewhere, paid considerably less than work on the mines and collieries’.7 Even though mine work was difficult and dangerous, it was still considered better than forced labour. So much so that, between 1886 and 1936, the majority of the Africans working on the mines came from Mozambique.

Running the gauntlet of modernity

By 1906, Wenela had built what Alexander calls an ‘extensive recruiting network’ in southern Mozambique: ‘Runners and recruiters guided and transported recruits by foot, sea and rail, between receiving stations, camps and compounds, towards their final destinations on the mines and collieries’.8 But what was it like to be a part of this network? Mining was an unpleasant business. As Leonard Thompson says, it was ‘arduous, unhealthy and dangerous’.9 The heat was intense and the stopes from which the ore was mined so narrow that, as Thompson says, workers had to crouch to get to it. Yet migrants kept coming. Wenela employed an army of recruiters called mine labour agents to find workers. The mining industry needed cheap labour because, with the price of gold fixed by the gold standard, there was little that mine-owners could control by way of costs, except what they paid their workers, especially Africans. African workers tried to improve their lot by going on strike numerous times in the early years of the industry. On the whole, their struggles did not succeed. For not only were they going against the owners, they were also challenging white workers who insisted, sometimes violently, on a white monopoly on skilled work. Recruiting workers was highly competitive and difficult, especially in the first decades of the gold mining industry. David Yudelman and Alan Jeeves describe these early days:

The mine labour agents had to be active and aggressive in acquiring their workers. They and their black and white assistants, styled runners, invaded the black rural areas to entice workers to sign up for the Rand. Fathers were induced to contract their children; chiefs to mobilize their followers; storekeepers to dispatch their debtor customers; white brigands connived with the mines to hijack workers bound for other employment.10

Having found and signed up their recruits, labour agents had to move them quickly and efficiently to the mines. A runner’s job was to deliver recruits on time to depots, from where they would be put on trains and sent to the mines. Runners worked under intense pressure for relatively little pay. In 1918, a runner earned two pounds, ten shillings a month.11 This begins to explain why Sitoye and Makuleke abandoned the old man and did not let his son stay with him. Until 1900, when Wenela was founded, recruitment was a ‘scandalously wasteful and expensive system’.12 By 1910, the mining industry needed about 200 000 recruits a year.13 Every healthy recruit counted. But labour agents would sometimes dupe recruits into signing contracts they did not understand or agents would ‘poach’ recruits from one another. Wenela introduced ‘order’ to the system. But travelling to the mines was still a perilous journey for migrants:

Once en route to the rand, an African would typically pass through the hands of two or three labour ‘touts’ (in effect having been sold from one to the next) before he reached his destination. Those who arrived safely at the mines after running a gauntlet of avaricious labour agents, government officials, predatory farmers and actual thieves, met a new set of horrors.14

Conservation and mining: An odd couple?

Where did the Kruger National Park fit into this story of movement and peril? To ask this is to raise a question about the relationship between the park and the mining industry, the National Parks Board and the Chamber of Mines. Simply put, the relationship between the park and the mining industry was characterised by what one mining industry official called ‘the most friendly co-operation’.15 While Stevenson-Hamilton was, on the whole, opposed to industry and what he saw as industry’s generally grubby designs on the park, he was friendly towards the mining industry.16 In fact, Wenela built one of the first roads in the park in 1920. The road, in the northern section of the park, was intended to improve the transportation of recruits from Portuguese territory. The road proved so useful that Wenela offered the National Parks Board an annual subsidy of five hundred pounds, ‘in consideration of the wear and tear caused by their heavy busses traveling in all weathers and several times a week’.17

Furthermore, the association was granted government permission in the 1920s to set up recruitment and processing camps in the park. The main camp was established in Pafuri in the north, with five rest camps set up at 25-mile intervals between Pafuri and a town north-west of the reserve called Louis Trichardt (Makhado). A wagon transport service was established in April 1921, covering the 130 miles between Pafuri and Louis Trichardt. A journey cost twelve pounds, but the sick travelled for free.18 By June 1922, the Pafuri road was handling 3 500 recruits a year. About 600 recruits came from Massengeri, a recruitment depot on the Mozambican side of the border, while a route that connected Maplanguene in Mozambique to Acornhoek and Zoekmekaar, two major towns on the South African side of the border, handled 3 000 recruits a year. All three routes traversed the park. As W Gemmill, Wenela’s manager and secretary, put it in 1922: ‘Half of these boys would be lost to the Industry if those routes did not exist.’19 One of the Wenela camps, Isweni, was donated to the Kruger National Park in 1941 and converted to a ranger station. The camps were crucial to the recruitment of labour. In 1918, for example, when Wenela set up camp at Pafuri, about 2 000 recruits were sourced from the park’s northern area by unregistered labour recruiters alone. But roads in the park transported more than recruits. They were also key to the development of the reserve as a tourist destination. Furthermore, migrants who went through the park would work briefly for the park to earn their pass and then move on to the mines. Wenela used the park to transport its recruits. In this sense, Wenela and the reserve benefited each other.

The park and the Chamber of Mines did not simply see themselves as friendly organisations. They also saw themselves as extensions of the state in territorial South Africa. To borrow words used by historian Jane Carruthers in a slightly different context, Wenela and the park saw their roles as being important for the ‘demonstration of white authority over Africans’.20 The creation of the Kruger National Park cemented laws imposed by the South African Republic banning Africans from hunting, owning firearms and keeping hunting dogs. ‘Wildlife protection … played a role in creating a proletariat as the industrialization of the Transvaal began at the turn of the century,’ says Carruthers, by limiting African access to land and independent livelihoods within the borders of the Transvaal.21

This does not mean, however, that the Kruger National Park and the mining industry worked in concert, with the one churning out proletarians and the other gobbling them up as soon as they were produced. Rather, a similarity lay in the ways in which both the Kruger National Park and the Chamber of Mines saw their operations as allowing for the projection and broadcasting of colonial power in places where it had only existed on paper before. Officials of the Kruger National Park and Wenela believed that their existence took colonial authority into remote corners of the African hinterland. AJ Limebeer, secretary of the Gold Producers’ Committee of the Chamber of Mines, said in a memorandum of 1943:

The opening up of the Pafuri area is an example of the exploratory work carried out by the WNLA [Wenela]. Before the association’s advent, Pafuri was accessible from the Union [of South Africa] only at certain times of the year, and always with difficulty. From the Portuguese side it was practically inaccessible. The nearest Portuguese officials, at Massengena, Secualacuola [sic] and Mapao would often not meet another European in six months.22

In the words of Limebeer, European power and control were measured by the presence of white bodies on the ground. Six months was too long to go without meeting a European. In that period, Africans may develop subversive behaviours or evidence too much agency. The colonial state could not allow that. So Wenela came into the breach, by making Pafuri accessible and European power visible.

This was not the only instance in which Wenela saw its presence in explicitly political terms. In the 1940s, Wenela recalled the role it played in the ‘taming’ of remote corners of northern South Africa and the Kruger National Park. The association said that until it moved into the northern section of the country, the area was a ‘hotbed for illicit labour recruiting, poaching, robbery, and every kind of illegality on the part of various undesirables, who had for long haunted that part of the country beyond the reach of any police’.23 This was an explicit acknowledgment of how Wenela saw itself in relation to state power, on the one hand, and ‘undesirables’, on the other. That this statement echoed Stevenson-Hamilton’s claim that the park controlled a place where ‘no other adequate control existed’ is testament to the similarity between the Kruger National Park and the Chamber of Mines.24 Limebeer put it this way:

It was the advent of the WNLA [Wenela] and the stationing of their agents at Pafuri and in the neighbouring parts of Portuguese East Africa with the establishment of a regular transport service by donkey wagon from Pafuri to Zoekmekaar, which proved the main factor in putting the undesirables out of business, and within a year or two they had all faded away.25

Limebeer’s letter was written to celebrate a ‘20-year connection’ between the Kruger National Park and Wenela and mentioned the thousands of recruits transported through the park to the mines:

There have been practically no complaints in regard to the behaviour of any natives in charge of the WNLA [Wenela]. Its vehicles have for years carried gratis the posts and parcels – often quite heavy consignments – of the Board and of the Rangers of all sections … between their various stations and the railway at Rubbervale and Zoekmekaar.26

The arrangement was also of benefit to the park. When Wenela donated a camp called Isweni to the park in 1941 as a ‘mark of appreciation of the facilities and privileges accorded to the association over a long period’, this proved ‘a source of profit to the park’, especially its staff. The camp, which came complete with ‘two single-roomed bungalows, mosquito-proofed, and was built of brick and concrete’, cost two hundred and twenty-six pounds sterling and had a book value of one hundred and nineteen pounds sterling.27

Clandestine emigrants

There is a gap between how agencies such as the Kruger National Park and the Chamber of Mines viewed themselves and migrant labourers and how Africans formally under the control of these agencies saw themselves and the agencies. We see displays of African agency not only in the reports from Stevenson-Hamilton complaining about poaching and trespassing by Portuguese Africans; we also see it in perennial complaints by Wenela officials about Africans making their way through the park to the mines and other places of employment without sanction from Wenela. For example, in a 1943 letter, a Portuguese official named Luis Costa alerted a senior official to ‘an ever increasing flow of clandestine emigration’ from the Portuguese side to South Africa.28

By July 1943, complaints about ‘clandestine emigration’ or ‘clandestine natives’ were becoming so common that Limebeer, the same secretary of the Gold Producers’ Committee, felt moved to write to his officials to explain that a ‘clandestine emigrant’ was in fact a technical term used by the Portuguese ‘and should not be taken necessarily to imply the ordinary meaning of the word clandestine, which is something underhand, hidden or secret’. Limebeer went on to explain that far from being subversive, ‘the flow of voluntary labour from Portuguese territory to adjoining countries is a normal, open proceeding throughout the whole of Portuguese East and West Africa’.29 However, Limebeer’s explanation did nothing to put his colleagues at ease. In June 1948, a Wenela official named Chapman wrote:

There is very little new in the situation and the natives continue to cross over without restraint. The Chef de Posto [Portuguese official in charge of an area], Massingir, complained bitterly that he had repeatedly sent more than two reports to headquarters over the past three years drawing the attention of the Authorities to the increasing number of natives crossing the border … I met a number of small parties of natives obviously making their way across the border. The composition of these parties never varied – one or two adults, usually experienced mine natives, and two or three youths between 15 and 17 years of age. In no case did they admit to me that they intended to cross the border.30

He went on to explain that the majority of clandestine natives ‘have found avenues of employment where wages are as high or higher than on the mines, and what is of more importance on their return they are not deprived of their earnings … by deductions on account of fares, customs etc.’ Africans making their way to South Africa did not have to pay Wenela transportation costs. They could also avoid the collection of taxes at the border post, holding on to all of their earnings. But these patterns of migration should not have come as a surprise to Wenela. Flows, connections and movements had always defined the border area. In fact, even Stevenson-Hamilton was forced to concede in the early days of the park that there were strong connections, blood ties even, between Africans who lived on either side of the border, making it a zone of transition. But the permeability of the border and the freedom of action did not mean that Africans could exist outside of the colony. They might have lived in and on the border, but they still needed passes to get from where they lived to the South African towns where the jobs were. They still needed to work in order to meet the obligations imposed on them by the state. But their employment options were not limited to the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. In 1960, a Wenela district manager spoke of a ‘vast labour force desiring employment along the [Kruger] Park boundaries’. The manager urged his bosses to lobby South Africa’s minister of labour to speak to his Portuguese counterpart about regulating the status of this vast source of labour:

This will ensure the continuance of these industrial and mining enterprises which are dependent on Portuguese clandestine labour for their existence … The WNLA would, in no way, be losers if this formality becomes legalised as the labour force concerned wish to have a short period near home where their wives can visit them between the longer contracts on the Free State mines.31

Africans who moved between the borders and found their own way to workplaces often acted on the basis of intelligence that travelled with people as they moved back and forth. Through this intelligence, they knew where the jobs were, which job paid what and when it made sense to sign up with Wenela. Many even knew that one of the best ways to acquire the much sought-after pass was to travel through the park, get yourself arrested and then provide unpaid labour for two weeks before being sent on your way with the necessary pass. ‘Clandestine emigration’ continued to be a serious issue for Wenela and state officials, whose primary concern was the management and regulation of African labour and the control of African movement. In fact, the issue continued to be such a problem that in November 1959, a Wenela official reacted angrily to a newspaper report about clandestine emigration to South Africa:

This thoughtless report has virtually made the Park, as a whole, the scapegoat of a position that the Bantu Affairs Department could not handle, and had no idea how to approach it. The illegal practice of obtaining unpaid labour has been in existence since time immemorial, willingly accepted by natives who don’t possess the ready cash to pay [five shillings] to pass through the park in search of work.32

Figure 9.2

Penny Siopis

from PRAY

2007

Stills from digital video projection, 2 mins, 48 secs, sound

Collection of Penny Siopis, courtesy of Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

He listed the steps taken by the park to contain the problem. There was no longer work for 14-day labourers, males needed passports to go through the park and African women were no longer allowed to pass through the park under any circumstances. But the official was not happy with this last injunction:

This has created great hardship on those Portuguese native females living adjacent to the border who wish to have medical attention, or hospitalization, or who wish to visit husbands working at Consolidated Murchison or Fosker [two mines close to the Kruger National Park]. This means the Natives will be forced to be dishonest with our organization, for which they really cannot be blamed.33

To understand why the Wenela official reacted angrily to the report, one must first understand how so-called clandestine emigration benefited both the Kruger National Park and Wenela. As Carruthers points out, the connection between the park and the mining industry did not provide the park with labour directly. Illegal immigrants were arrested or voluntarily gave themselves up to the warden, who was also a special justice of the peace. The immigrants were arrested and put to work in the park during their imprisonment. At the end of their term in jail, they were granted a pass that allowed them to seek employment in the mines and elsewhere. This ‘casual system of labour’ was not without fault. Park staff did not keep criminal records, for one. In 1924, the park responded to complaints about this by introducing mobile prisons that were moved around the park to where labour was needed. The institution was ended in 1926 when South Africa and Portugal signed a new labour convention.34 By the 1950s, the situation was such that Wenela’s district manager for Zoekmekaar was able to report:

All natives found within the Park boundaries are closely interrogated as to their reason for being in the Park. If they state that they are proceeding to the mines they proceed to Zoekmekaar. If they state their object is to reach Lowveld farmers or mines along the Escarpment they are automatically charged a fee to pass through the Park. If they have no money to pay for their permits they are automatically charged and convicted as trespassers, the punishment being a period of labour.35

The official added that he was unaware how arrested natives were distributed by the park to serve their sentences. The official’s point apparently came in response to suggestions that park officials might have set themselves up as labour recruiters. ‘I cannot imagine the Park Authorities becoming involved in recruiting natives for sundry employers,’ he said. The official was correct. The park did not become a labour recruitment agency, but its actions came close to blurring distinctions between itself and Wenela.

‘Well-dressed’ Africans on the move

On 30 July 1950, two ‘educated, well-dressed’ Africans from Mozambique who had travelled through the park via Pafuri to Zoekmekaar – a major terminus west of the park for the transportation of migrant labourers – were rejected as potential recruits and sent back to Mozambique.36 The two men had travelled from Mozambique on lorries operated by the Wenela. T Carruthers, the association’s district manager for Zoekmekaar, turned the men back after being told by fellow recruits that the men had boasted to them during their ride through the park that they had no intention of going to the mines and were merely using the association’s transport services to get to the Transvaal. Word of Carruthers’s decision reached the Johannesburg headquarters of the mining company for which he worked. The administrator chided Carruthers for his decision, saying he was ‘under moral obligation to send these two natives to the Rand and not to reject them’.37 GO Lovett, Carruthers’s boss, tried to explain:

Mr. Carruthers sent for [the two Africans] and found that they were educated, well-dressed Natives. He questioned them and asked for all their papers. Then he discovered that they had Transvaal passes and had previously worked two or three times for private employers in Pretoria. The inference that they were fraudulently using the Association was obvious and, consequently, he had no hesitation in rejecting them.38

Lovett backed Carruthers ‘as this practice of using the Association as a means of leaving Portuguese territory without any intention of carrying out their obligations is one that has grown recently and is to be guarded against.39 The above story brings to view at least two of the migrants for whom the park was a zone of movement, fluidity and permeable borders. What emerges from their story is a lesson about how even in the interstices of colonial power, Africans were able to carve out spaces of autonomy. This is not to valorise African agency or to make it more profound than it might have been. It is, rather, to say that colonial authority itself was not as absolute as it sometimes presented itself. It is also to call attention to the fact that the railways and associated modes of transport did not only serve to construct an imaginary geography of white nationhood. They also helped Africans negotiate complex relations with modern South Africa.

Conclusion

This chapter is concerned with the relationship between the Chamber of Mines and the National Parks Board, the Kruger National Park and Wenela. It shows the complex connections between capitalism and conservation in colonial and apartheid South Africa. It looks at the (indirect) role played by officials of the Kruger National Park and its predecessor, the Sabi Game Reserve, in the advent of industrial capitalism in southern Africa. In particular, it highlights the relationship between the migrant labour system and the Kruger National Park as a zone of movement and as a transit corridor for migrant labourers moving back and forth between colonial South Africa and Portuguese East Africa. This was not a straightforward relationship, to be sure. This chapter is set, ultimately, against readings of the Kruger National Park that insist on seeing the park as a pristine wilderness untouched and unaffected by the advent and development of industrial capitalism in southern Africa. Far from being a natural hotspot removed from the messiness of industrial capitalism, the Kruger National Park was in fact an important part of the story of capitalism in southern Africa. It was a key part of the economic, social and political development of this region.

Notes

1. University of Johannesburg, The Employment Bureau of Africa (Teba)/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 197/16.

2. Letter from CL Harries to magistrate of Louis Trichardt, 5 October 1920, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 197/16.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Transvaal Administration Reports for 1903, Annexure H.

6. P Harries, Work, Culture and Identity: Migrant Labourers in Mozambique and South Africa, c.1860–1910 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 1994).

7. P Alexander, ‘Oscillating Migrants, “Detribalized Families” and Militancy: Mozambicans on Witbank Collieries, 1918– 1927’, Journal of Southern African Studies 27.4 (2001), 509.

8. Ibid.

9. L Thompson, A History of South Africa (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2006), 163.

10. D Yudelman and A Jeeves, ‘New Labour Frontiers for Old: Black Migrants to the South African Gold Mines, 1920–85’, Journal of Southern African Studies13.1 (1986), 104.

11. Unnumbered NRC pad, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 197/9.

12. Yudelman and Jeeves, ‘New Labour Frontiers’, 104.

13. W Beinart, Twentieth-Century South Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 70.

14. A Jeeves, ‘The Control of Migratory Labour on the South African Gold Mines in the Era of Kruger and Milner’, Journal of Southern African Studies 2.1 (1975), 16. Jeeves is writing about the period before the South African War in 1898–1902, but his conclusions still hold for the first three decades of the twentieth century.

15. Pad 1, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

16. J Carruthers, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995), 95.

17. University of Johannesburg, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B, Pad 1.

18. Unnumbered NRC pad, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 197.

19. Letter from W Gemmill, 9 June 1922, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 197.

20. Carruthers, Kruger, 94.

21. J Carruthers, ‘“Police Boys” and Poachers: Africans, Wildlife Protection and National Parks, the Transvaal 1902–1950’, Koedoe 36.2 (1993), 13.

22. AJ Limebeer, Memorandum, 1943, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

23. Ibid.

24. South African National Archives, NTS 7618, 28/329.

25. AJ Limebeer, Memorandum, 1943, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

26. Ibid.

27. Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

28. Letter from Luis Costa, 1943, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

29. AJ Limebeer, Memorandum, 1943, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

30. Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Carruthers, Kruger, 95.

35. Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

36. Pad 1, Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives ,WNLA 46/B.

37. Teba/Chamber of Mines Archives, WNLA 46/B.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.