Appendices

The Inscriptions

Margherita Guarducci’s decoding of the almost two-thousand-year-old inscriptions on the Graffiti Wall and in other locations in the Necropolis is one of the epic works of epigraphy and archeology. Not only did it lead to the discovery of Peter’s relics, but also to a new direct understanding of the actual beliefs of early Christians — proven not through the prism of later writings, but through the physical evidence of their contemporary inscriptions. Before Guarducci, the inscriptions were dismissed by the early excavators as meaningless and indecipherable.

Guarducci’s work to understand the inscriptions, which consumed three to five years of her life, is best described in her highly technical 1960 book, The Tomb of Saint Peter (Hawthorn), and in her later works like Peter: The Rock on Which the Church Is Built (1977, Vatican) and The Primacy of the Church of Rome (1991, Rusconi Libri, Milan). Guarducci also wrote many articles from 1958 until 1995 about her discoveries and the remarkable inscriptions she uncovered and deciphered.

The inscriptions on the Graffiti Wall resemble a forest of trees, one overlaid on top of another. Guarducci first used photography and magnification to produce more coherent images. She recognized that the inscriptions represented a code used by early Christians to express religious beliefs in a way indecipherable to their Roman persecutors, and to portray parables and allegories that express profound truths recognizable only to people of faith. Christ himself taught his followers in parables (cf. Matthew 13), such as the Prodigal Son and the Good Shepherd. Early Christian art reflects this, and the Graffiti Wall inscriptions were no different: they spoke by allusion and parable.

Through a careful process of photography, magnification, and actual physical examination in the Necropolis over many months, Guarducci accomplished this tedious task. She was able to identify the actual inscriptions one by one. She surveyed the Roman world and found the same code symbols were often used by early Christians, particularly in Rome, but also in the far reaches of the Empire from the second to the sixth centuries. After long study, she found three keys to breaking this code:

1. Almost every alphabetic phonic symbol had in turn a hidden symbolic meaning.

2. The joining of letters through signs of union expressed religious concepts.

3. The use of symbols over letters combined thoughts. For instance, the letter “P” overlaid with key symbols recalled Peter, keeper of the keys to the Kingdom.

By way of example, Guarducci found on the Graffiti Wall and on an early Christian tombstone elsewhere the letters “TE” together or joined with a line. This symbol reflects the Cross (T) reopening Eden (E) or Paradise. Alpha (A) and Omega (Ω), the first and last Greek letters, reflect the beginning and the end. They appear repeatedly with both symbols of Christ (because Christ is the beginning and the end) and reversed with proper names (this person’s end is only his beginning). “RA” meant “I am the Resurrection and the beginning of Life.”

These and many other inscriptions appeared not only on the Graffiti Wall, but also on other previously undecipherable inscriptions found in places ranging from the Colosseum to numerous tombstones. At another point on the Graffiti Wall, the Greek word “NICA” (victory) was written directly over the symbols for Christ, Mary (M), and Peter. On the adjoining Red Wall, built around 160, Guarducci found coded inscriptions meaning “Peter is here” — as it turns out, these provided a marker and were not merely a prayer.

The theological implications of the Graffiti Wall to a Christian are profound and moving. Peter occupies a central role in the Church, and it is clear the early Christians honored him and prayed to him for aid. From earliest times, Christians believed in eternal life unlocked by Christ’s death on the Cross. Christianity was not simply an evolving cult. By 150–300, the basic tenets of Christianity were believed so deeply that Christians would risk their lives even to inscribe them on a wall marking the site of a martyr’s burial.

As Guarducci wrote, “The epigraphs are unusually precious witnesses bringing the direct, live echo of past events.” They remain “a voice that we must hear.”231

The Conroe Oil Field

Scientists believe that more than sixty-five million years ago, an asteroid, believed to measure between six and nine miles in diameter, struck the ocean offshore of Yucatan, Mexico, leaving an immense crater and killing most of life on Earth, including the dinosaurs. The massive crater was actually located by geologists on the Texas Gulf Coast, who noticed a ring of oil-bearing sands down the Texas Coast which they believed were laid down by an immense tsunami more than 9,800 feet high, produced by the asteroid. The wave was still over 2,000 feet high when it deposited sands in the area of what would someday be the Conroe oil field.232

More than twelve million years after the tsunami, the so-called Eocene Age began, and the Conroe field lay at the bottom of the ocean for many million years. Under the ocean, plant and animal life died and settled to the bottom, slowly decaying. There were coral reefs as high as four hundred feet, traced much later in the vicinity of the field. Deep beneath the surface, an unlikely agent would produce a very unlikely formation.

Salt — the same as common table salt — slowly built up, and being lighter than the soil, it began to push its way upward. Think of a fist pushing through layers of napkins. Over long ages, this “fist” of salt produced a dome filled in its center and on its flanks with decaying plant and animal life. Slowly the dome filled at its top with a massive cap of natural gas — highly combustible. Under the gas and sands pushed up by the inexorable movement of salt, the dome filled with oil in immense quantities — millions of years later to be the lifeblood of an emerging industrial civilization. This area, now known as the Conroe field, would rise from the ocean and fall back again many times during the roughly thirty million years after its formation in the Eocene Age.

The search for oil began in the late nineteenth century, beginning first in Pennsylvania with Edwin Drake. It spread to Texas in the twentieth century. The East Texas Oil Field was discovered in 1930. At that time, one certain rule in the oil business (based on numerous dry holes) was that there was no oil east of Conroe. Seismic and other data gathered by the large oil companies proved this. The dry holes and bankrupt dreams of numerous explorers supported the evidence. Meanwhile, the great salt dome, containing incalculably large amounts of gas and oil, waited almost one mile below the earth’s surface.

Along came George Strake in 1931. After leasing more than 8,500 acres for a pittance, he went to every major oil company seeking an industry partner. He had none of the detailed seismic data, production history, reservoir engineering, torsion balance, or the like which underlay even the wildest wildcat. His prospect was where repeated dry holes, beginning in 1919, had proven there could be no oil. In addition, seismic and torsion balance data proved this prospect silly and unlikely.

He had only surface evidence: water the cattle would not drink and the anomaly of creeks that flowed the wrong way. The oil companies, with good evidence, believed him a crazy, lone-wolf wildcatter peddling another dry hole. But he believed (as he later said) that he was a team of two with God on his shoulder. He drilled, but hit only the natural gas cap — nearly worthless in those days. There was still no hint of anything below. He drilled again on the flank, and a mile below the surface hit the sea of oil, which had been waiting for him for almost fifty-three million years. The great field’s wait was over. Shortly the area above it would become a beehive of human activity.

George Strake died many years before discovery of the great asteroid, confirmed by its vast underwater crater off Yucatan and the layer of iridium dust it deposited seventy-seven million years ago across the Earth. But he would have no problem at all believing that a celestial visitor was the beginning of his great oilfield.

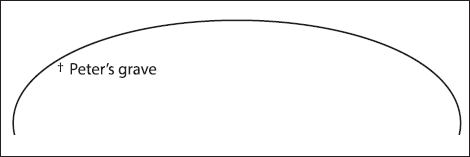

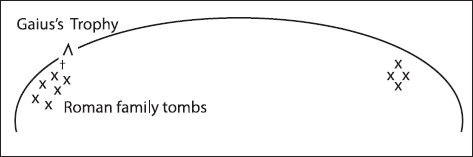

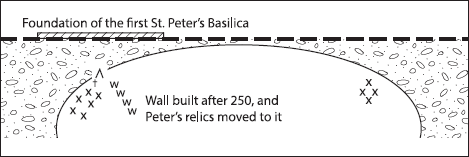

The Story of Vatican Hill

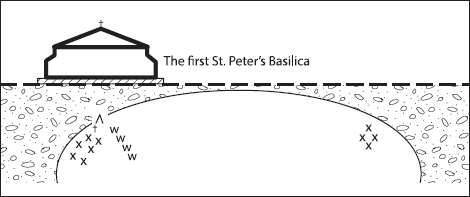

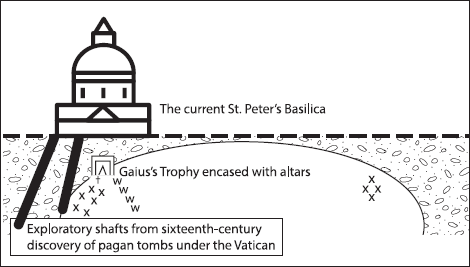

(Diagrams are figurative and not to scale.)

I.

Circa A.D. 64–66: Peter died and was buried on Vatican Hill.

II.

Circa 150: Construction of Gaius’s Trophy and many Roman tombs.

Circa 326: Construction began on the first St. Peter’s Basilica. Workers used millions of tons of fill to level the foundation.

IV.

Circa 360: First St. Peter’s Basilica completed. The basilica was built centered over the apostle’s grave. Except for the encasing of Gaius’s Trophy, and following the collapse of Rome in 476, the Necropolis was forgotten. The underground graves slept silently for a thousand years.

1506: Construction began on the new St. Peter’s Basilica. The new basilica was built on the old foundation, remaining centered on the apostle’s grave. Gaius’s Trophy was encased with altars circa 600, 1000, and 1500, but the hill and the forgotten tombs remained unexplored until 1941.

Timeline

About A.D. 30 |

Peter meets Jesus and begins to follow him. |

64–66 |

Paul and then Peter are executed in Nero’s persecution after the great fire of Rome. Peter’s body is discarded on nearby Vatican Hill. |

90–300 |

Many family tombs are built by wealthy Roman families on Vatican Hill. |

About 100 |

Early Christian accounts refer to Peter’s burial in Rome. |

About 150 |

A structure is built near Peter’s grave by Christians and later written about by Gaius. |

250–300 |

Peter’s bones are moved into the Graffiti Wall, either during the late persecutions of Christians or during the construction of Constantine’s basilica. |

319–333 |

Construction of the first St. Peter’s Basilica by Constantine. Graves and Roman family tombs are covered with fill in order to level the hill. |

337–476 |

Disintegration of the Western Roman Empire. Buried tombs on Vatican Hill are forgotten. |

1453 |

Fall of Constantinople. |

1505–1655 |

Construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica on the old foundation. At least three unsuccessful secret efforts are made to find Peter’s tomb. |

1939 |

During the burial of Pius XI beneath the Vatican, Christian and Roman graves are found. Pius XII decides to search for Peter. |

1940 |

Pius’s emissary, Father Walter Carroll, secures promise of unlimited financing from George Strake. |

Excavations continue secretly despite World War II. Many efforts are made by Carroll to combat Nazis and help the Jews. |

|

1946–1948 |

Strake works with Carroll on the Italian parish church project. A flood nearly destroys the excavation project under the Vatican. |

1950 |

Pius XII announces the discovery of Peter’s tomb and ongoing study of bones found by Ferrua. |

1951 |

Strake visits Rome and meets with the excavators and Pius XII. |

1952 |

Margherita Guarducci is brought into the project and given supervision of it. She begins her study of the inscriptions. |

1958 |

The bones found by Ferrua are determined by forensic exam not to belong to Peter. Pius XII dies. |

1962–1965 |

Extensive testing and other evidence reveal the bones found within the Graffiti Wall to be Peter’s. Guarducci decodes the inscriptions. |

1966 |

Pope Paul VI recognizes the bones found within the Graffiti Wall as Peter’s. |

1978 |

Paul VI dies and is buried near Peter. Guarducci is fired from the excavation project. The bones Paul VI identified as Peter’s are shipped to storage by Father Antonio Ferrua. |

1978–1999 |

Guarducci solves numerous mysteries. Bitter controversy rages between Guarducci and Ferrua over the Graffiti Wall bones. |

2013 |

Following re-examination and additional testing, Pope Francis reaffirms the Church’s belief that Guarducci’s conclusions indicate that the Graffiti Wall bones were Peter’s. |

The Hottest Ticket in Rome

Numerous magazine articles call the Scavi Tour “the hottest ticket in Rome,” and countless travelers have found it their most interesting tour in Europe. The extraordinary Roman murals and the simple Christian graves transport one back to the height of Roman power and at the same time symbolize the futility and illusion of earthly empires.

The Tour — not suitable for those with claustrophobia — must be arranged well in advance through the Vatican Excavation Office. Requests may be submitted to Scavi@FSP.VA or by fax to +390669873017.

The fortunate traveler who manages to secure a reservation will experience an extraordinarily interesting and deeply inspiring visit.