Il Diavolo Incarnato. Paolo Uccello’s equestrian memorial to Sir John Hawkwood, the notorious fourteenth-century English mercenary and scourge of Italy commemorated by a grateful city in Florence’s Duomo.

Gallipoli. A soldier salutes at the grave prepared for the remains of New Zealand dead, killed in the savage fighting for Chunuk Bair on 8 August 1915. After a gap of five years identification was often impossible, but the bones have been arranged in a forlorn attempt to give an individual integrity to each burial.

Thiepval, 1 August 1932. Fabian Ware – ‘The Great Commemorator’ and moving spirit of the Imperial War Graves Commission – with the Prince of Wales at the unveiling of Lutyens’s Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. Lutyens can be seen in the background on the left.

Vendresse Cemetery, south of Laon in the Department of the Aisne, France. In its utter simplicity and pastoral quiet, perhaps the archetypal Commission cemetery. It contains the graves of more than seven hundred men killed, principally, in the fighting of 1914 and 1918, of whom only 327 have names.

‘Have you news of my boy Jack?’ . Rudyard Kipling and his son John, killed at the age of eighteen at the Battle of Loos in 1915. As both the Poet of Empire and bereaved father who never recovered from his son’s loss, Kipling enjoyed an immense influence as the Imperial War Graves Commission’s first literary advisor.

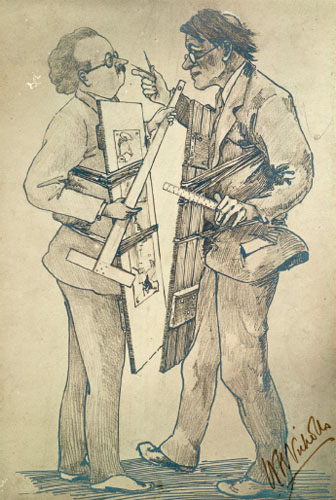

Armed for battle. William Nicholls’s caricature of the Commission architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, who had badly fallen out over the building of New Delhi and brought their differences with them to France.

The official war artist Francis Dodd’s portrait of his friend Charles Holden, the most austere of the Principal Architects in charge of the cemeteries along the old Western Front.

Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Serre Road Cemetery, No. 2. Just one of the seemingly interminable line of cemeteries that mark the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and the 1918 German spring advance over the same bitterly won ground. The cemetery was begun in 1917 and enlarged after the war as the process of concentration began. Almost 5,000 of the 7,127 burials are unidentified.

Etaples. A view back to the cemetery entrance, showing one of the two arched pylons, with the perpetually motionless stone flags that Lutyens had wanted to employ on his Whitehall Cenotaph.

Etaples, 1919: Life and death. Sir John Lavery’s beautiful painting of the great base-camp cemetery, and in the distance a passing train. Fabian Ware had been determined that trains should be able to pause here for passengers to pay their moment’s respect to the cemetery’s 11,000 dead.

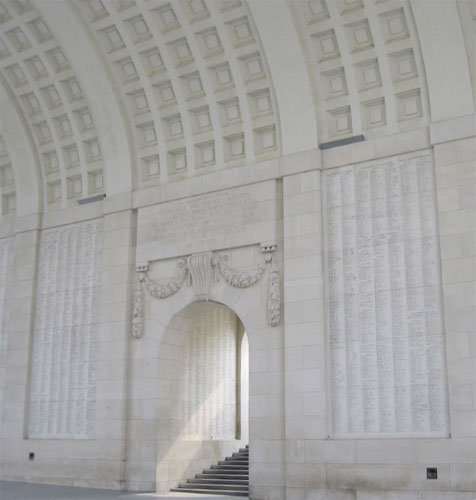

Lutyens’s Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, the greatest and most challenging of all the Commission’s works. On it are inscribed the names of 72,085 soldiers who were killed on the Somme and Ancre and have no known grave. On the slope below are the graves of 300 British dead and alongside them and visible here, of 300 French.

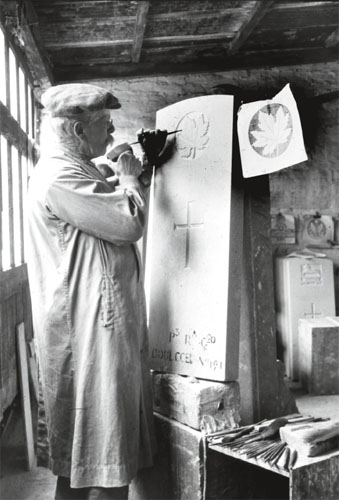

A stonemason works on the headstone of a Canadian soldier buried in France. Simplicity, equality and uniformity were the guiding principles of its design but nothing in the Commission’s history would cause such bitter debate.

The devastated town of Ypres, as the architect Reginald Blomfield first saw it in 1919, when he began preparations for his great Memorial to the missing of the Ypres Salient. The war-artist Will Longstaff attended the unveiling ceremony in 1927, and the result was his visionary ‘Menin Gate at Midnight’, with its ghost army marching out over the same moonlit landscape across which almost every British and Empire army unit had once gone into battle.

‘These intolerably nameless names.’ The central arch of Blomfield’s Menin Gate, where the names of almost 55,000 ‘officers and men who fell in the Ypres Salient but to whom the fortunes of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death’ are recorded.

Sacred Places. Lone Pine Cemetery, Turkey. Nowhere have the Imperial War Graves Commission Cemeteries and the battles they commemorate played so important a part in the creation of national identities as here in Gallipoli. The Lone Pine Memorial records the names of almost 5,000 Australian and New Zealand soldiers who have no known grave.

Etaples. The funeral of a St John’s Ambulance Brigade nursing sister, Annie Bain, killed in an air raid on 1 June 1918.

The Commission headstone over her grave. She lies among the 10,816 who are buried here.

Cultural differences. Käthe Kollwitz’s deeply moving ‘Mourning Parents’, a portrait of grief and a monument to her son, Peter, killed in the early, heady days of war and buried here in the Vladslo German war cemetery.

The graves of French dead from Verdun, and in the background the monstrous Douaumont ossuary.

Tyne Cot Cemetery, near Ypres. The work of Sir Herbert Baker, and the largest of the Commission cemeteries in Belgium. In the foreground can be seen Lutyens’s Stone of Remembrance, and beyond it and the original scattering of graves, covered in stone and surmounted by Blomfield’s Cross of Sacrifice, the German bunkhouse that gave the cemetery its name.

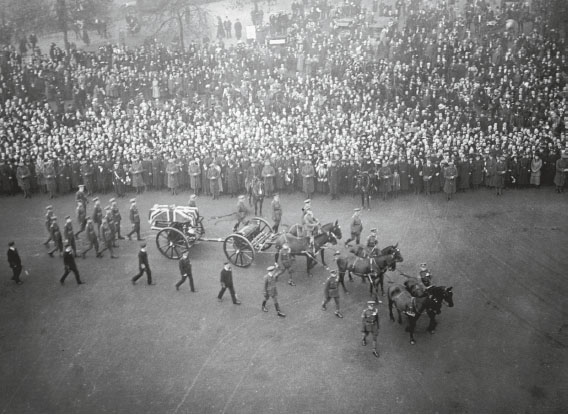

11 November 1920. The funeral procession of the Unknown Warrior, an outpouring of national grief and one of the great cathartic moments in the post-War history of a Britain coming to terms with its immense losses.

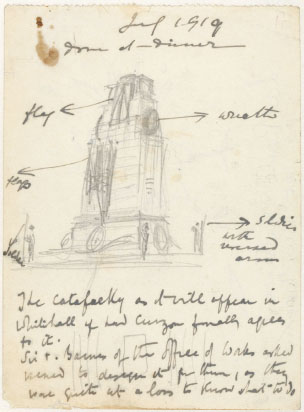

‘Done at dinner.’ Lutyens’s rapid sketch of a monument for the Peace Day Celebrations of July 1919. Originally made of wood and plaster, it immediately became such a popular focus of national mourning that the Government decided to replicate it in stone on the same site in Whitehall.

Armistice Day 1920, the unveiling of Lutyens’s cenotaph, or ‘empty tomb’. ‘The majestic unveiling ceremony by the king … is part of our national history,’ wrote Lutyens. ‘My hope is that, as the years pass into centuries, the cenotaph will endure as a sacred symbol of remembrance.’

Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere. The great centrepiece of Stanley Spencer’s extraordinary commemoration of the War, painted for the Oratory commissioned by the Behrends in memory of Henry Sandham who died in 1919 from an illness contracted during the Macedonian Campaign.