Where Old and New Worlds Collide

A mother-daughter trip brings memories, cherished and painful, to life.

BY NINA STROCHLIC

The quaint and cobbled streets of Krakow, Poland, where millions flock to remember those who perished at the hands of the Nazis

A few times a year throughout my childhood, my mother and I hauled a tan suitcase from the spare room. She would pop open the single working hinge and fish out stacks of sepia-toned photographs and frayed papers—curfew extensions, identity cards, immigration forms. We’d sort through the haphazard piles and decaying photo albums.

The suitcase held the remaining tangible links to my grandparents’ prewar lives and a slightly more robust postwar collection. We tried to decipher the old-fashioned, loopy scrawl that explained each picture. In them, she, a chic, blond-bobbed woman with a square face and wide smile, and he, a dapper and slightly older man, stared up at us. Holding these tangible relics, the past felt closer.

At the outbreak of World War II, my grandparents were forced from their homes in Poland and into labor and concentration camps. On nights the suitcase came out, we’d watch videos of my jovial grandpa remembering the miles of frozen marches and how he won my grandmother’s affection in the displaced persons camp after the war by scraping together ingredients to bake her a cake. Soon after, they married, got visas for Cuba, and jumped ship in New York City while en route.

Sabina, my grandmother, died long before I was born, and Carl, my grandfather, passed away when I was five, but I knew their stories by heart. Like the one when my grandmother’s parents and brother survived the war only to return to the rural village where they’d stored their belongings and be murdered by its postwar inhabitants.

“Never forget” wasn’t just a phrase for my family; it was a mantra.

But it was also a challenge: How could we remember what we never experienced? After years of dragging out the old suitcase, the pictures became two-dimensional, the stories took on a folkloric quality, and the pages of correspondence we’d exchanged with surviving relatives failed to satiate our curiosity.

MY MOM AND I DECIDED to set out for our ancestral land. Though my grandfather swore he’d never return to Poland, we felt drawn to fill in the backdrop for our family history. I thought of it as time travel—I imagined Poland was a country of ghosts, a crowd of bearded men walking down cobblestoned streets and hastily evacuated shtetls. A country stuck in the loop of 1939.

But the Krakow we encountered, with its soaring castle- and cafélined medieval squares, was nothing like that. Virtually unscathed by the invading Germans, it had the charm of a young, modern city set amid the mystique of an ancient one. On a warm July day, my mom and I landed armed with a jumble of addresses pulled from the sharp memory of an elderly cousin of my grandmother’s, and began a scavenger hunt in search of my grandparents’ past. Bursting with Jewish tours, museums, and shops, the city catered to tourists like us—pilgrims unearthing their heritage.

Krakow’s hub of activity for 1,000 years, its Main Square

Krakow was a treasure trove of Jewish history and ephemera. Antique shops were stuffed with war-era newspapers, magazines, and boxes of unclaimed family photographs. A sprawling suburban flea market peddled oxidized menorahs and ashtrays decorated with Hitler’s face. The Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, had hosted the city’s Jewish population for nearly half a millennium, but fallen into disrepair after World War II, when its inhabitants were moved into the outlying ghetto before being shipped to concentration camps.

In the 1990s, after an onslaught of attention following the release of Schindler’s List, which was filmed in the district, the Kazimierz underwent a face-lift, with a focus on Jewish heritage. Now, thousands stream in for the annual Jewish Cultural Festival each summer; school groups and brigades of Israeli soldiers tour the historic synagogues; tourists dine at traditional Jewish eateries; and patrons browse Judaica Krakow’s bookstores and museum exhibits.

On a corner in the center of the city’s Old Town, we found the storefront site of the seasonally rotating ice cream parlor cum fur shop my great-grandparents, Fela and Moses, owned. Crossing a bridge into what once was the ghetto, we photographed a music school that now occupied the building my grandmother, her parents, aunt, and cousins were moved to in March 1941. As Jews were sent into ghettos, my blond-haired and blue-eyed grandmother was hidden for a time outside the city by a brave Christian Pole of noble descent, but she eventually returned to Krakow. He was later caught and badly beaten for this attempt to save a Jew. Two years later, Sabina and her aunt were taken to Plaszow, the camp outside Krakow. They’d spend two months after that in Auschwitz, where, upon arrival, Sabina’s aunt was given an orange ball gown to wear and Sabina was dressed in the fabric from an umbrella. They found this so hysterically grotesque, my grandmother later told a cousin, that they laughed until they cried. Their last wartime stop was Bergen-Belsen, where my grandmother and her aunt were when Allied forces arrived in 1945 to liberate the camp.

It was in the displaced persons camp of Bergen-Belsen where she and my grandfather met and were married, in a group wedding of 48 couples on the Jewish holiday of Lag BaOmer. More than a year after being freed, the new couple and her relatives set out for Cuba, hopping off in New York under the care of a distant cousin and promise of a “less-than-two-month” stay, according to her nonimmigrant visa. Her nationality at the time is listed as “without.” In the interim, they’d started collecting the photos that now fill our fraying suitcase: David Ben-Gurion speaking to a large rally at Bergen-Belsen, a wedding day pose with my grandmother’s family, a blurry shot of the Statue of Liberty as their ship passed by.

KRAKOW WAS A BEAUTIFUL CITY to wander through, but our aim was to see my grandmother’s family’s prewar apartment, the childhood home of a woman I knew only through photographs and who remained a faint memory to my mother, who was only 10 when Sabina died at the age of 37. Rising from the middle of Krakow, Wawel Royal Castle, a Polish renaissance complex, keeps a watchful eye on its city, and it was in the high-class streets surrounding it that we knew my grandmother grew up.

Our quest was shorted by a false start: a tour of 28 Podzamcze, a gift shop on a corner across from the castle. My mother let loose an uncontrollable stream of tears while the flabbergasted salesgirl tried in vain to find signs that the small space had once been an apartment. Unsuccessful, my mom plucked a small babushka magnet off a wall as a souvenir. Next to the row of colorful doll mementos was a selection of small magnetic Jews with black hats, curled payot and massive coins clutched in their hands.

We walked out disappointed in a lack of connection and wondering if we had the wrong address. But before we could right it, we were off for a day to Auschwitz, a bleak tour of the war’s most notorious death factory. From there, we hopped a train west to Bedzin, my grandfather’s hometown.

Connections

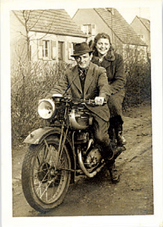

In this aging picture, carefully stashed in a worn suitcase in my parents’ house in Eugene, Oregon, my grandparents, Carl and Sabina Strochlic, pose on a motorbike in Europe after World War II. We aren’t sure when exactly this photo was taken, but it seems to fit into the time line between leaving Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp, and taking a ship from France to Cuba that allowed them to disembark in New York City.

To me, this scene perfectly captures my dashing grandfather sweeping my grandmother off her feet in the postwar wasteland of Europe. —Nina Strochlic

We found ourselves in a train compartment with no English speakers and little clue to where we were headed. A sign language conversation with a roving conductor signaled we should disembark at what was, we realized too late, a graffiti-covered old train station miles from Bedzin’s city lights we saw glittering against the sunset on the horizon. So, we set off on foot, walking for an hour past decrepit Soviet-style row houses without a sign of life.

We arrived late in Bedzin, a small city of about 60,000, and checked into our hotel. As my mom gave our name at reception, a cry of recognition came from a cluster of chairs in the lobby. An amiable elderly man jumped up with surprising dexterity and introduced himself as a former Bedzin resident and a friend of the family’s before and after the war. By coincidence we were staying at the same hotel as a tour group for the Bedzin Holocaust survivors and that next day was a commemoration of the anniversary of the 1942 ghetto liquidation.

We accompanied his group on a tour of the town, watching rows of Israeli and Polish soldiers line up at attention to face the ghetto memorial, their buttons gleaming under the 95-degree sun as survivors took the podium. We traveled to a church that, after the Nazis burned down the town’s synagogue, had taken in escaping Jews, and heard a terrifying account from one of the few who had been saved. Nearby, as the group started climbing up the steps of Bedzin’s ancient castle, my mom and I slipped away, counting the address numbers down the main street until we stood facing my grandfather’s apartment building.

Carl had left town early in the war, off a tip that volunteering for labor camps was preferable to sticking around until the death camp deportations. He pushed his birthdate to three years later (a change he would only admit at his 80th birthday party) and filtered through 12 to 15 work camps before being liberated and brought to Bergen-Belsen. That tip proved unimaginably fortuitous: Much of Bedzin’s Jewish population was later sent to Auschwitz.

We stared from across the street at the second floor of the boxy yellow building that had housed my grandfather, his parents, and seven siblings, some 70 years earlier. A burly man in a black T-shirt stood on the balcony off the floor we thought to be my grandfather’s, his thick arms folded against the railing and a puff of smoke rising from his lips. Maybe it was the increasingly noticeable language barrier, but we decided asking for a peek into his residence would be unwise. We turned and walked back down the street. The glimpse was satisfying—my grandfather had shared his stories with us already. We both knew that the real hope was to see my grandmother’s apartment—a tangible piece of the life of a woman who remained a mystery to me and a hazy figure to my mother. We had one last shot.

THAT NIGHT, WE TOOK A TRAIN back to Krakow. It was our final day in Poland and we were armed with another address to try—20 Podzamcze—from a cousin of my grandmother’s. She instructed us it was on the first floor, “the windows on the left of the entry when looking at the house from the street.” A 1941 German census of Krakow Jews classified the property as a “two bedroom, one living room, one kitchen” apartment.

We found what we believed to be my grandmother’s building, a classic limestone structure, on a street encircling the Wawel Castle, and just a half block up from the corner souvenir shop. Without an apartment number, we buzzed futilely, and had nearly given up when a nattily dressed businessman produced keys to the front door and we slipped in behind him.

Standing inside the dim hallway, we lingered, dragging the video camera over ceramic tiles that surely predated our family’s residency. My mother, holding a note in Polish that explained our quest, rapped on the wooden door of No. 2, which seemed to possess the building’s exterior left windows. A middle-aged woman with short brown hair cracked it open and greeted us hesitantly. Her eyes flitted over the handwritten note, and confusion melted into warmth. In choppy English, she introduced herself as Marta and ushered us in.

The apartment was beautiful, with ornate inlaid wood floors, and almost entirely original fixtures. “It hasn’t been remodeled, except for the bathroom, since my mother bought it in 1949,” said Marta. Her mother, bedridden and sleeping in the living room, had purchased it from a woman who occupied the apartment during the war after my grandparents were forced out. My mom’s expression mirrored my own disbelief. I could almost imagine my great-grandparents stoking a fire in the green ceramic-tiled heater that stretched to the ceiling in a corner of the kitchen. The harrowing circumstances that transferred the apartment from our family’s hands to Marta’s were overshadowed by our incredible luck. We talked to her for an hour, lingering in the apartment that, save a world war, could have been our home.

That evening, over dinner of traditional Polish pierogies surrounded by fire dancers and roving polka bands on the city’s medieval square, my mom and I checked off a list of trip goals. We had dug up a trail of our family history through Krakow and Bedzin, filling a 55-year-long void for my mom—and constructed a stage for the stories of some of her parents’ lives. My grandfather may not have approved of our visit had he been around, but we’d found a bittersweet relationship between his Poland and the 21st-century nation struggling to balance a bloody past with a cosmopolitan present. The country no longer conjured only fleeing Jews and ghetto walls. Along with them were pierogi festivals, imposing castles, and welcoming Poles like Marta.

A few months later, we received an email from Marta. Her mom had passed away and she’d moved into a different apartment in the building. “I’m very happy when you still contact with me,” Marta wrote. “I also don’t want to lose touch with you, so we see you one day!” My mother and I joked about checking if the apartment was on the market and moving back to Poland, but instead stashed our mementos, the babushka magnet from the souvenir shop, and our photos in the tan suitcase where the old and new worlds could finally merge.

NINA STROCHLIC is a reporter at the Daily Beast in New York City. She has an insatiable fascination with genealogy and exploring foreign lands.

The author with her mother during their Krakow visit

GET TO KNOW POLAND

• TASTE

One communist-era Krakow relic worth visiting is a bar mleczny (bahrr MLETCH-nih), or milk bar, so named because the no-frills cafeterias served plenty of dairy and just about anything but then scarce meat. Associated with cheap Polish food ladled out cheerlessly, the once ubiquitous milk bars have dwindled to a handful. For a somewhat gentrified version of the original concept, try Milkbar Tomasza, where, for about $6, you can fill up on soup and an entrée, such as pierogi or potato pancakes.

• TOUR

The new Museum of the History of Polish Jews (jewishmuseum.org.pl/en) in the heart of World War II’s Warsaw Ghetto tells the 1,000-year history of Poland’s Jewish population through artifacts, personal stories, and interactive exhibits in eight distinct galleries.

• READ

The compelling memoir-travelogue The Pages in Between (Touchstone, 2008), by New York Daily News reporter Erin Einhorn, underscores the frustrations and complexities of researching family history in a foreign country—specifically in Bedzin, Poland. Einhorn searched for—and found—the Catholic family who hid her mother there during the Holocaust.