On January 27, 1999, a tiger went walking through the township of Jackson, New Jersey. According to the Tiger Information Center, a tiger’s natural requirements are “some form of dense vegetative cover, sufficient large ungulate prey, and access to water.” By those measures, Jackson is really not a bad place to be a tiger. The town is halfway between Manhattan and Philadelphia, in a corner of Ocean County—an easy commute to Trenton and Newark, but still a green respite from the silvery sweep of electric towers and petroleum tanks to the north, and the bricked-in cities and mills farther south. Only forty-three thousand people live in Jackson, but it is a huge town, a bit more than a hundred square miles, all of it as flat as a tabletop and splattered with ponds and little lakes. A lot of Jackson is built up with subdivisions and Wawa food markets, or soon will be, but the rest is still primordial New Jersey pinelands of broom sedge and pitch pine and sheep laurel and peewee white oaks, as dense a vegetative cover as you could find anywhere. The local ungulates may not be up to what a tiger would find in more typical habitats, like Siberia or Madhya Pradesh—there are just the usual ornery and overfed pet ponies, panhandling herds of white-tailed deer, and a milk cow or two—unless you include Jackson’s Six Flags Wild Safari, which is stocked with zebras and giraffes and antelopes and gazelles and the beloved but inedible animal characters from Looney Tunes.

Nevertheless, the Jackson tiger wasn’t long for this world. A local woman preparing lunch saw him out her kitchen window, announced the sighting to her husband, and then called the police. The tiger slipped into the woods. At around five that afternoon, a workman at the Dawson Corporation complained about a tiger in the company parking lot. By seven, the tiger had circled the nearby houses. When he later returned to the Dawson property, he was being followed by the Jackson police, wildlife officials, and an airplane with an infrared scope. He picked his way through a few more back yards and the scrubby fields near Interstate 195, and then, unfazed by tranquillizer darts fired at him by a veterinarian, headed in the general direction of a middle school; one witness described seeing an “orange blur.” At around nine that night, the tiger was shot dead by a wildlife official, after the authorities had given up on capturing him alive. A pathologist determined that he was a young Bengal tiger, nine feet long and more than four hundred pounds. Nothing on the tiger indicated where he had come from, however, and there were no callers to the Jackson police reporting a tiger who had left home. Everyone in town knew that there were tigers in Jackson—that is, everyone knew about the fifteen tigers at Six Flags Wild Safari. But not everyone knew that there were other tigers in Jackson, as many as two dozen of them, belonging to a woman named Joan Byron-Marasek. In fact, Jackson has one of the highest concentrations of tigers per square mile anywhere in the world.

Byron-Marasek is famously and purposely mysterious. She rarely leaves the compound where she lives with her tigers, her husband, Jan Marasek, and scores of dogs, except to go to court. On videotapes made of her by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, she looks petite and unnaturally blond, with a snub nose and a small mouth and a startled expression. She is either an oldish-looking young person or a youngish-looking old person; evidently, she has no Social Security number, which makes her actual age difficult to establish. She has testified that she was born in 1955 and was enrolled in New York University in 1968; when it was once pointed out that this would have made her a thirteen-year-old college freshman, she allowed as how she wasn’t very good with dates. She worked for a while as an actress and was rumored to have appeared on Broadway in Tom Stoppard’s play Jumpers, swinging naked from a chandelier. A brochure for her tiger preserve shows her wearing silver boots and holding a long whip and feeding one of her tigers, Jaipur, from a baby bottle. On an application for a wildlife permit, Byron-Marasek stated that she had been an assistant tiger trainer and a trapeze artist with Ringling Brothers and L. N. Fleckles; had trained with Doc Henderson, the illustrious circus veterinarian; and had read, among other books, The Manchurian Tiger, The World of the Tiger, Wild Beasts and Their Ways, My Wild Life, They Never Talk Back, and Thank You, I Prefer Lions.

The Maraseks moved to Jackson in 1976, with Bombay, Chinta, Iman, Jaipur, and Maya, five tigers they had got from an animal trainer named David McMillan. They bought land in a featureless and barely populated part of town near Holmeson’s Corner, where Monmouth Road and Millstone Road intersect. It was a good place to raise tigers. There was not much nearby except for a church and a few houses. One neighbor was a Russian Orthodox priest who ran a Christmas-tree farm next to his house; another lived in a gloomy bungalow with a rotting cabin cruiser on cement blocks in the front yard.

For a long time, there were no restrictions in New Jersey on owning wildlife. But beginning in 1971, after regular reports of monkey bites and tiger maulings, exotic-animal owners had to register with the state. Dangerous exotic animals were permitted only if it could be shown that they were needed for education or performance or research. Byron-Marasek held both the necessary New Jersey permit and an exhibitor’s license from the United States Department of Agriculture, which supervises animal welfare nationally.

After arriving in Jackson, Byron-Marasek got six more tigers—Bengal, Hassan, Madras, Marco, Royal, and Kizmet—from McMillan and from Ringling Brothers. The next batch—Kirin, Kopan, Bali, Brunei, Brahma, and Burma—were born in the back yard after Byron-Marasek allowed her male and female tigers to commingle. More cubs were born, and more tigers were obtained, and the tiger population of Holmeson’s Corner steadily increased. Byron-Marasek called her operation the Tigers Only Preservation Society. Its stated mission was, among other things, to conserve all tiger species, to return captive tigers to the wild, and “to resolve the human/tiger conflict and create a resolution.”

“I eat, sleep, and breathe tigers,” Byron-Marasek told a local reporter. “I never take vacations. This is my love, my passion.” A friend of hers told another reporter, “She walks among her tigers just like Tarzan. She told me, ‘I have scratches all along the sides of my rib cage and both my arms have been cut open, but they’re just playing.’ Now, that’s love.”

You know how it is—you start with one tiger, then you get another and another, then a few are born and a few die, and you start to lose track of details like exactly how many tigers you actually have. As soon as reports of the loose tiger came in, the police asked everyone in Jackson who had tigers to make sure that all of them were accounted for. Six Flags Wild Safari had a permit for fifteen and could account for all fifteen. At the Maraseks’, the counting was done by a group of police and state wildlife officers, who spent more than nine hours peering around tumbledown fences, crates, and sheds in the back yard. Byron-Marasek’s permit was for twenty-three tigers, but the wildlife officers could find only seventeen.

Over the years, some of her tigers had died. A few had succumbed to old age. Muji had an allergic reaction to an injection. Diamond had to be euthanized after Marco tore off one of his legs. Marco also killed Hassan in a fight in 1997, on Christmas Eve. Two other tigers died after eating road-killed deer that Byron-Marasek now thinks might have been contaminated with antifreeze. But that still left a handful of tigers unaccounted for.

The officers filmed the visit:

“Joan, I have to entertain the notion that there are five cats loose in town, not just one,” an officer says on the videotape.

Byron-Marasek’s lawyer, Valter Must, explains to the group that there was some sloppy math when she filed for the most recent permit.

The officers shift impatiently and make a few notes.

“For instance, I don’t always count my kids, but I know when they’re all home,” Must says.

“You don’t have twenty-three of them,” one of the officers says.

“Exactly,” Must says.

“You’d probably know if there were six missing,” the officer adds.

“I would agree,” Must says.

On the tape, Byron-Marasek insists that no matter how suspicious the discrepancy between her permit and the tiger count appears, the loose tiger was not hers. No, she does not know whom it might have belonged to, either. And, gentlemen, don’t stick your fingers into anything, please: I’m not going to tell you again.

The officers ask to see Byron-Marasek’s paperwork. She tells them that she is embarrassed to take them into her house because it is a mess. The tiger quarters look cheerless and bare, with dirt floors and chain-link fences and blue plastic tarps flapping in the January wind, as forlorn as a bankrupt construction site. During the inspection, a ruckus starts up in one of the tiger pens. Byron-Marasek, who represents herself as one of the world’s foremost tiger authorities, runs to see what it is, and reappears, wild-eyed and frantic, yelling, “Help me! Help! They’re going to … they’re going to kill each other!” The officers head toward the tiger fight, but then Byron-Marasek waves to stop them and screams, “No, just Larry! Just Larry!”—meaning Larry Herrighty, the head of the permit division, about whom she will later say, in an interview, “The tigers hate him.”

The day of the tiger count was the first time that the state had inspected the Maraseks’ property in years. New Jersey pays some attention to animal welfare—for instance, it closed the Scotch Plains Zoo in 1997 because of substandard conditions—but it doesn’t have the resources to monitor all its permit holders. There had been a few complaints about the tigers: in 1983, someone reported that the Maraseks played recordings of jungle drums over a public-address system between 4 and 6 A.M., inciting their tigers to roar. The State Office of Noise Control responded by measuring the noise level outside the compound one night, and Byron-Marasek was warned that there would be monitoring in the future, although it doesn’t appear that anyone ever came back. Other complaints, about strange odors, were never investigated. Her permit was renewed annually, even as the number of animals increased.

Anyone with the type of permit Byron-Marasek had must file information about the animals’ work schedule, but the state discovered that it had no records indicating that her tigers had ever performed, or that anyone had attended an educational program at Tigers Only. The one tiger with a public profile was Jaipur, who weighed more than a thousand pounds, and who, according to his owner, was listed in the Guinness World Records as the largest Siberian tiger in captivity. Later, in court, Byron-Marasek also described Marco as “a great exhibit cat”—this was by way of explaining why she doted on him, even though he had killed Diamond and Hassan—but, as far as anyone could tell, Marco had never been exhibited.

Now the state was paying attention to the Tigers Only Preservation Society, and it wasn’t happy with what it found. In court papers, D.E.P. investigators noted, “The applicant’s tiger facility was a ramshackle arrangement with yards (compounds), chutes, runs, and shift cages … some of which were covered by deteriorating plywood, stockade fencing and tarps, etc.… The periphery fence (along the border of the property), intended to keep out troublemakers, was down in several places. There was standing water and mud in the compound. There was mud on the applicant’s tigers.” There were deer carcasses scattered around the property, rat burrows, and a lot of large, angry dogs in separate pens near the tigers. Suddenly, one wandering tiger seemed relatively inconsequential; the inspectors were much more concerned about the fact that Byron-Marasek had at least seventeen tigers living in what they considered sorry conditions, and that the animals were being kept not for theatrical or educational purposes but as illegal pets. Byron-Marasek, for her part, was furious about the state’s inspections. “The humiliation we were forced to suffer is beyond description,” she said later, reading from a prepared statement at a press conference outside her compound. “Not only did they seriously endanger the lives of our tigers—they also intentionally attempted to cut off their food supply.”

The one suspicion that the state couldn’t confirm was that the loose tiger had belonged to Joan Byron-Marasek. DNA tests and an autopsy were inconclusive. Maybe he had been a drug dealer’s guard animal, or a pet that had got out of hand and was dropped off in Jackson in the hope that the Tiger Lady would take him in. And then there were the conspiracy theorists in town who believed that the tiger had belonged to Six Flags, and that his escape was covered up because the park is the biggest employer and the primary attraction in town. In the end, however, the tiger was simply relegated to the annals of suburban oddities—a lost soul, doomed to an unhappy end, whose provenance will never be known.

It is not hard to buy a tiger. Only eight states prohibit the ownership of wild animals; three states have no restrictions whatsoever, and the rest have regulations that range from trivial to modest and are barely enforced. Exotic-animal auction houses and animal markets thrive in the Midwest and the Southeast, where wildlife laws are the most relaxed. In the last few years, dealers have also begun using the Internet. One recent afternoon, I browsed the Hunts Exotics Web site, where I could have placed an order for baby spider monkeys ($6,500 each, including delivery); an adult female two-toed sloth ($2,200); a Northern cougar female with blue eyes, who was advertised as “tame on bottle”; a black-capped capuchin monkey, needing dental work ($1,500); an agouti paca; a porcupine; or two baby tigers “with white genes” ($1,800 each). From there I was linked to more tiger sites—Mainely Felids and Wildcat Hideaway and NOAH Feline Conservation Center—and to pages for prospective owners titled “I Want a Cougar!” and “Are You Sure You Want a Monkey?” It is so easy to get a tiger, in fact, that wildlife experts estimate that there are at least fifteen thousand pet tigers in the country—more than seven times the number of registered Irish setters or Dalmatians.

One reason that tigers are readily available is that they breed easily in captivity. There are only about six thousand wild tigers left in the world, and three subspecies have become extinct just in the last sixty years. In zoos, though, tigers have babies all the time. The result is thousands of “surplus tigers”—in the zoo economy, these are animals no longer worth keeping, because there are too many of them, or because they’re old and zoo visitors prefer baby animals to mature ones. In fact, many zoos began breeding excessively during the seventies and eighties when they realized that baby animals drew big crowds. The trade in exotic pets expanded as animals were sold to dealers and game ranches and unaccredited zoos once they were no longer cute. In 1999, the San Jose Mercury News reported that many of the best zoos in the country, including the San Diego Zoo and the Denver Zoological Gardens, regularly disposed of their surplus animals through dealers. Some zoo directors were so disturbed by the practice that they euthanized their surplus animals: according to the Mercury News, the director of the Detroit Zoo put two healthy Siberian tigers to sleep, rather than risk their ending up as mistreated pets or on hunting ranches. Sometimes dealers buy surplus animals just for butchering. An adult tiger, alive, costs between two hundred and three hundred dollars. A tiger pelt sells for two thousand dollars, and body parts from a large animal, which are commonly used in aphrodisiacs, can bring five times as much.

Between 1990 and 2000, Jackson’s population increased by almost a third, and cranberry farms and chicken farms began yielding to condominiums and center-hall Colonials. It was probably inevitable that something would come to limn the town’s changing character, its passage from a rural place to something different—a bedroom community attached to nowhere in particular, with clots of crowdedness amid a sort of essential emptiness; a place practically exploding with new people and new roads that didn’t connect to anything, and fresh, clean sidewalks of cement that still looked damp; the kind of place made possible by highways and telecommuting, and made necessary by the high cost of living in bigger cities, and made desirable, ironically, by the area’s quickly vanishing rural character. A tiger in town had, in a roundabout way, made all of this clear.

In 1997, a model house was built on the land immediately east of the Maraseks’ compound, and in the next two years thirty more houses went up. The land had been dense, brambly woods. It was wiped clean before the building started, so the new landscaping trees were barely toothpicks, held in place with rubber collars and guy wires, and the houses looked as if they’d just been unwrapped and set out, like lawn ornaments. The development was named The Preserve. The houses were airy and tall and had showy entrances and double-car garages and fancy amenities like Jacuzzis and wet bars and recessed lighting and cost around three hundred thousand dollars. They were the kind of houses that betokened a certain amount of achievement—promotion to company vice-president, say—and they were owned by people who were disconcerted to note that on certain mornings, as they stood outside playing catch with their kids or pampering their lawns, there were dozens of buzzards lined up on their roofs, staring hungrily at the Maraseks’ back yard.

“If someone had told me there were tigers here, I would have never bought the house,” one neighbor said not long ago. His name is Kevin Wingler, and where his lawn ends, the Maraseks’ property begins. He is a car collector, and he was in his garage at the time, tinkering with a classic red Corvette he had just bought. “I love animals,” he said. “We get season passes every year for the Six Flags safari, and whenever I’m out I always pet all the cows and all the pigs, and I think tigers are majestic and beautiful and everything. But we broke our ass to build this house, and it’s just not right. I could have bought in any development! I even had a contract elsewhere, but the builder coaxed me into buying this.” He licked his finger and dabbed at a spot on the dashboard and laughed. “This is just so weird,” he said. “You’d think this would be happening in Arkansas, or something.”

I drove through The Preserve and then out to a road on the other side of the Maraseks’ land. This was an old road, one of the few that had been there when the Maraseks moved in, and the houses were forty or fifty years old and weathered. The one near the corner belonged to the owner of a small trucking company. He said that he had helped Joan Byron-Marasek clean up her facilities after the state inspection. “I knew she was here when I moved here fifteen years ago,” he said. “Tigers nearby? I don’t care. You hear a roar here and there. It’s not a big concern of mine to hear a roar now and then. The stench in the summer was unbearable, though.” He said he didn’t think that the wandering tiger was one of Byron-Marasek’s, because her tigers were so dirty and the tiger that was shot looked clean and fit. He said that, a few years before, Byron-Marasek had come by his house with a petition to stop the housing development. He didn’t sign it. “The new neighbors, they’re not very neighborly,” he said. “They’re over there in their fancy houses. She’s been here a lot longer than they have.” Still, he didn’t want to get involved. “Those are Joan’s own private kitty cats,” he said, lighting a cigarette. “That’s her business. I’ve got my life to worry about.”

The tiger that had walked through Jackson for less than eight hours had been an inscrutable and unaccountable visitor, and, like many such visitors, he disturbed things. A meeting was held at City Hall soon after he was shot. More than a hundred people showed up. A number of them came dressed in tiger costumes. They demanded to know why the roving tiger had been killed rather than captured, and what the fate of Byron-Marasek’s tigers would be. Somehow the meeting devolved into a shouting match between people from the new Jackson, who insisted that Byron-Marasek’s tigers be removed immediately, and the Old Guard, who suggested that anyone who knew the town—by implication, the only people who really deserved to be living there—knew that there were tigers in Holmeson’s Corner. If the tigers bothered the residents in The Preserve so much, why had they been stupid enough to move in? Soon after the meeting, the state refused to renew Byron-Marasek’s wildlife permit, citing inadequate animal husbandry, failure to show theatrical or educational grounds for possessing potentially dangerous wildlife, and grievously flawed record-keeping. The township invoked its domestic-animals ordinances, demanding that Byron-Marasek get rid of some of her thirty-odd dogs or else apply for a formal kennel license. The homeowners in The Preserve banded together and sued the developer for consumer fraud, claiming that he had withheld information about the tigers in his off-site disclosure statement, which notifies prospective buyers of things like toxic-waste dumps and prisons which might affect the resale value of a house. The neighborhood group also sued Byron-Marasek for creating a nuisance with both her tigers and her dogs.

Here was where the circus began—not the circus where Joan Byron-Marasek had worked and where she had developed the recipe for “Joan’s Circus Secret,” which is what she feeds her tigers, but the legal circus, the amazing three-ring spectacle that has been going on now for several years. Once the state denied Byron-Marasek’s request to renew her permit, she could no longer legally keep her tigers. She requested an administrative review, but the permit denial was upheld. She appealed to a higher court. She was ordered to get rid of the animals while awaiting the results of her appeal of the permit case. She appealed that order. “Tigers are extremely fragile animals,” she said at a press conference. “Tigers will die if removed by someone else. If they are allowed to take our tigers, this will be a tiger holocaust.” Byron-Marasek won that argument, which allowed her to keep the tigers during her permit appeal, as long as she agreed to certain conditions, including preventing the tigers from breeding. During the next couple of years, two of her tigers had cubs, which she hid from state inspectors for several weeks. She declared that the state was trying to destroy her life’s work. Through her Tigers Only Web site, she supplied form letters for her supporters to send to state officials and to the D.E.P.:

DEAR SENATOR:

I am a supporter of the Tigers Only Preservation Society and Ms. Joan Byron-Marasek in her fight to keep her beautiful tigers in their safe haven in Jackson, New Jersey.… We should all be delighted with the fact that these tigers live together in peaceful harmony with their environment and one another right here in New Jersey. If anything, the T.O.P.S. tigers should be revered as a State treasure, and as such, we citizens of New Jersey should all proudly and enthusiastically participate in this State-wide endeavor to keep the T.O.P.S. tigers in New Jersey.

If we are successful … future generations of constituents will be eternally grateful for your efforts in keeping these magnificent creatures living happily in our midst for all to enjoy.

In the meantime, legal proceedings dragged on while she changed attorneys five times. Her case moved up the legal chain until it reached the state’s appellate court. There, in December, 2001, the original verdict was finally and conclusively upheld—in other words, Byron-Marasek was denied, once and for all, the right to keep tigers in New Jersey.

The Byron-Marasek case reminded some people of the 1995 landmark lawsuit in Oregon against Vickie Kittles, who had a hundred and fifteen dogs living with her in a school bus. Wherever Kittles stopped with her wretched menagerie, she was given a tank of gas and directions to get out of town. She ended up in Oregon, where she was finally arrested. There she faced a district attorney named Joshua Marquis, who had made his name prosecuting the killer of Victor the Lobster, the twenty-five-pound mascot of Oregon’s Seaside Aquarium who had been abducted from his tank. When the thief was apprehended, he threw Victor to the ground, breaking his shell; no lobster veterinarian could be found and Victor died three days later. Marquis was able to persuade a jury that the man was guilty of theft and criminal mischief. He decided to prosecute Kittles on grounds of animal neglect. Kittles contended that she had the right to live with her dogs in any way she chose. Marquis argued that the dogs, which got no exercise and no veterinary care and were evidently miserable, did not choose to live in a school bus. Vickie Kittles was convicted, and her dogs were sent to foster homes around the country.

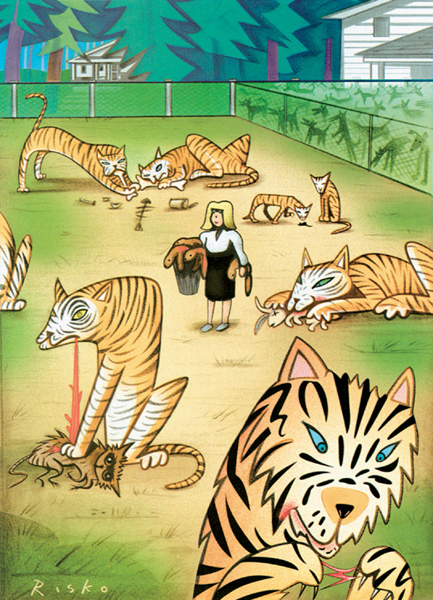

“Cat, anyone?” (illustration credit 15.6)

The Kittles case was the first prominent suit against an “animal hoarder”—a person who engages in the pathological collecting of animals. Tiger Ladies are somewhat rare, but there are Cat Ladies and Bird Men all over the country, and often they end up in headlines like “201 CATS PULLED FROM HOME” and “PETS SAVED FROM HORROR HOME” and “CAT LOVER’S NEIGHBORS TIRED OF FELINE FIASCO.” A study published by the Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium says that more than two-thirds of hoarders are females, and most often they hoard cats, although dogs, birds, farm animals, and, in one case, beavers, are hoarded as well. The median number of animals is thirty-nine, but many hoarders have more than a hundred. Hoarders, according to the consortium, “may have problems concentrating and staying on track with any management plan.”

On the other hand, animal hoarders may have boundless energy and focus when it comes to fighting in court. Even after Byron-Marasek lost her final appeal, she devised another way to frustrate the state’s efforts to remove her tigers. The Department of Environmental Protection had found homes for the tigers at the Wild Animal Orphanage in San Antonio, Texas, and come up with a plan for moving the tigers there on the orphanage’s Humane Train. In early January, the superior-court judge Eugene Serpentelli held a hearing on the matter. The Tiger Lady came to court wearing a dark-green pants suit and square-toed shoes and carrying a heavy black briefcase. She was edgy and preoccupied and waved off anyone who approached her except for a local radio host who had trumpeted her cause on his show and a slim young man who huddled with her during breaks. The young man was as circumspect as she was, politely declining to say whether he was a contributor to the Tigers Only Preservation Society or a fellow tiger owner or perhaps someone with his own beef with the D.E.P.

Throughout the hearing, Byron-Marasek dipped into her briefcase and pulled out sheets of paper and handwritten notes and pages downloaded from the Internet, and passed them to her latest lawyer, who had been retained the day before. The material documented infractions for which the Wild Animal Orphanage had been cited by the U.S.D.A. over the years—storing outdated bags of Monkey Chow in an unair-conditioned shed, for instance, and placing the carcass of a tiger in a meat freezer until its eventual necropsy and disposal. None of the infractions were serious and none remained unresolved, but they raised enough questions to delay the inevitable once again, and Judge Serpentelli adjourned to allow Byron-Marasek more time to present an alternate plan. “Throughout this period of time, I’ve made it clear that the court had no desire to inflict on Mrs. Marasek or the tigers any hardship,” the Judge announced. “But the tigers must be removed. I have no discretion on the question of whether they should be removed, just how.”

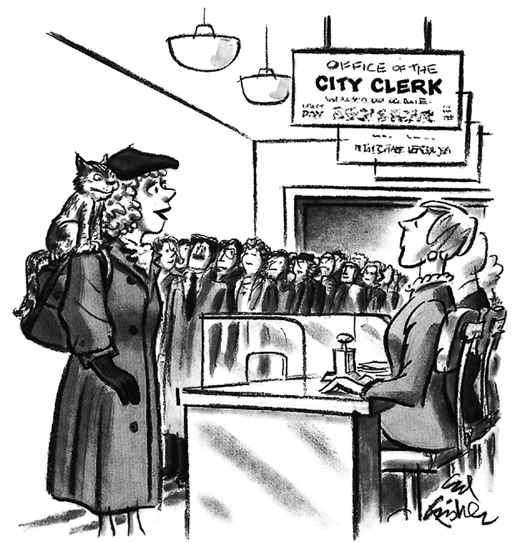

“We want to register a domestic partnership.”

Before the state acts, however, there is a good chance that the Tiger Lady will have taken matters into her own hands. Last fall, in an interview with the Asbury Park Press, she said that she was in the process of “buying land elsewhere”—she seemed to think it unwise to name the state—and suggested that she and her dogs and her tigers might be leaving New Jersey for good. Typically, people who have disputes with the authorities about their animal collections move from one jurisdiction to another as they run into legal difficulties. If they do eventually lose their animals, they almost always resurface somewhere else with new ones: recidivism among hoarders is close to a hundred percent. In the not too distant future, in some other still-rural corner of America, people may begin to wonder what smells so strange when the wind blows from a certain direction, and whether they actually could have heard a roar in the middle of the night, and whether there could be any truth to the rumors about a lady with a bunch of tigers in town.

I had been to Jackson countless times, circled the Maraseks’ property, and walked up and down the sidewalks in The Preserve, but I had never seen a single tiger. I had even driven up to the Maraseks’ front gate a couple of times and peered through it, and I could see some woolly white dogs scuffing behind a wire fence, and I could see tarps and building materials scattered around the house, but no tigers, no flash of orange fur, nothing. I wanted to see one of the animals, to assure myself that they really existed.

One afternoon, I parked across from the Winglers’ and walked past their garage, where Kevin was still monkeying around with his Corvette, and then across their backyard and beyond where their lawn ended, where the woods thickened and the ground was springy from all the decades’ worth of pine needles that have rained down, and I followed the tangy, slightly sour smell that I guessed was tiger, although I don’t think I’d ever smelled tigers before. There was a chain-link fence up ahead. I stopped and waited. A minute passed and nothing happened. A minute more, and then a tiger walked past on the other side of the fence, its huge head lowered and its tail barely twitching, the black stripes of its coat crisscrossed with late-day light, its slow, heavy tread making no sound at all. It reached the end of the fence and paused, and turned back the other way, and then it was gone.

| 2002 |