Pete has been having piano lessons for five weeks. I have planned each one carefully, and written a report on how it went for my course file.

Teaching a fully grown mathematical type is indeed different from teaching a ten-year-old girl. When I introduce him to middle C, he says, “Why isn’t it middle A? That would be more logical.” My attempts to answer this question lead to a long discussion about the principles of tonality, the diatonic scale, the development of clefs and the harmonic ratios between notes in terms of oscillations per second. Which is not exactly what I had planned for Lesson 2.

I did most of my practice in the early morning, with the thick velvet curtains of the garden-facing piano room tightly drawn, and my parents asleep upstairs at the front of the house.

Now, in Itchingford, it is about eight o’clock in the evening. Pete is practising the piano and I am in the office, trying not to listen as he blunders through the same phrase over and over again. “You are NOT going to go downstairs,” I tell myself firmly, and concentrate hard on The Perfect Wrong Note, a radical book about music learning that I am reading for my course. The botched repetition continues. I grit my teeth. But it does no good. There is something weirdly zombified about what he is doing. He is wasting effort, and probably getting fed up. I have to intervene—it will be better in the longer run.

So I hurry downstairs and open the living-room door.

Pete is sitting at the piano, splodging through his piece for the fiftieth time. But there is another noise as well, a sort of mixed humming and buzzing, which at first I cannot identify at all.

Then I catch sight of a small silver radio perched on top of the piano, its slim shiny aerial extended to maximum length. All at once, what I am hearing makes total sense.

Pete is practising, but he is also listening to a football match on Radio 5 Live.

“PETE!” I say loudly. “What on earth are you doing?”

He stops playing and looks round. “Er … I was sort of multi-tasking,” he replies, sheepishly.

“Pete,” I say, exasperated. “Honestly, it’s not worth it. You’ll get much more benefit from ten minutes’ practice if you’re really concentrating, than from half an hour going round in circles because you’re listening to the football at the same time. Believe me, it’s not efficient.”

“Oh all right, point taken,” he says, switching off the radio.

“Look, you’ve probably done enough for tonight anyway. Why don’t you just stop and listen to the match?”

So he does.

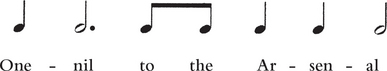

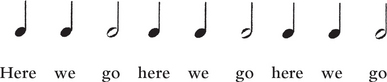

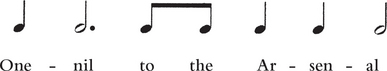

As it turns out, when it comes to Pete’s progress on the piano, football is not entirely unhelpful. I find the following written in his piano notebook, as a practice exercise in the notation of rhythm: