THE HISTORY OF THE THIRD CALENDER, THE SON OF A KING.

WHAT I am going to relate, most honourable lady, is of a very different nature from that of the stories you have already heard. Each of the two Princes, who have recited their histories, has lost an eye, as it were by the power of destiny, while I have lost mine in consequence of my own fault. I have sought out my misfortune, as you will find by what I am going to tell.

“I am called Agib, and am the son of a King, whose name was Cassib. After his death I took possession of his throne, and established my residence in the same city which he had made his capital. This city, which is situated on the sea coast, has a remarkably handsome and safe harbour, with an arsenal sufficiently extensive to supply an armament of a hundred and fifty vessels of war, always lying ready for service on any occasion, and to equip fifty merchantmen, and as many sloops and yachts, for the purposes of amusement and pleasure on the water. My kingdom was composed of many beautiful provinces, and also contained a number of considerable islands, almost all of which were situated within sight of my capital.

“The first thing I did was to visit the provinces; I then made them arm, had my whole fleet equipped, and went round to all my islands in order to conciliate the affections of my subjects, and to confirm them in their duty and allegiance. After I had been at home some time, I set out again; and these voyages, by giving me some slight knowledge of navigation, infused such a taste for it into my mind, that I resolved to go on a voyage of discovery beyond my islands. For this purpose I equipped only ten ships; and embarking in one of them, we set sail.

“During forty days our voyage was prosperous, but on the night of the forty-first the wind became adverse, and so violent, that we were driven at the mercy of the tempest, and thought we should have been lost. At break of day, however, the storm abated, the clouds dispersed, and the rising sun brought fine weather with it. We now landed on an island, where we remained two days, to take in provisions. Having done this, we again put to sea. After ten days’ sail we began to hope to see land; for since the night of the storm I had altered my intention, and determined to return to my kingdom—but I then discovered that my pilot knew not where we were. In fact, on the tenth day, a sailor who was ordered to the mast-head for the purpose of scanning the horizon reported that to the right and left he could perceive only the sky and sea, but that straight before him he observed a great blackness.

“At this intelligence the pilot changed colour; and throwing his turban on the deck with one hand, he struck his face with the other, and cried out, ‘Ah, my lord, we are lost! Not one of us can possibly escape the danger which threatens us, and with all my experience, it is not in my power to ensure the safety of any one of you. Speaking thus, he began to weep like one who thought his destruction inevitable; and his despair spread alarm and fear through the whole vessel. I asked him what reason he had for this outburst of grief. ‘Alas!’ he answered, ‘the tempest we have experienced has so driven us from our track, that by midday to-morrow we shall find ourselves near yonder dark object, which is a black mountain, consisting entirely of a mass of loadstone, that will soon attract our fleet, on account of the bolts and nails in the ships. To-morrow, when we shall have come within a certain distance, the power of the loadstone will be so great, that all the nails will be drawn out of the keels, and attach themselves to the mountain; our ships will then fall in pieces and sink. As it is the property of a loadstone to attract iron, and as its own power increases by this attraction, the mountain towards the sea is entirely covered with the nails that belonged to the immense number of ships which it has destroyed; and this mass of iron fragments, at the same time, preserves and augments the virtue of attraction in the loadstone.

“ ‘This mountain,’ continued the pilot, ‘is very steep, and on the summit there is a large dome, made of fine bronze, and supported upon columns of the same metal. At the top of the dome there is also a bronze horse, with the figure of a man upon it. The rider’s breast is covered by a leaden breastplate, upon which some talismanic characters are engraven; and there is a tradition that this statue is the principal cause of the loss of the many vessels and men who have been drowned in this place; and that it will never cease from being destructive to all who shall have the misfortune to approach it, until it is overthrown.’ When the pilot had finished his speech, he wept anew, and his tears excited the grief of the whole crew. As for myself, I did not doubt that I was now approaching the end of my days. Every man began to think of his own preservation, and to try every possible means to save himself; and during this period of uncertainty, we all agreed to make the survivors, if any should be saved, the heirs of the rest.

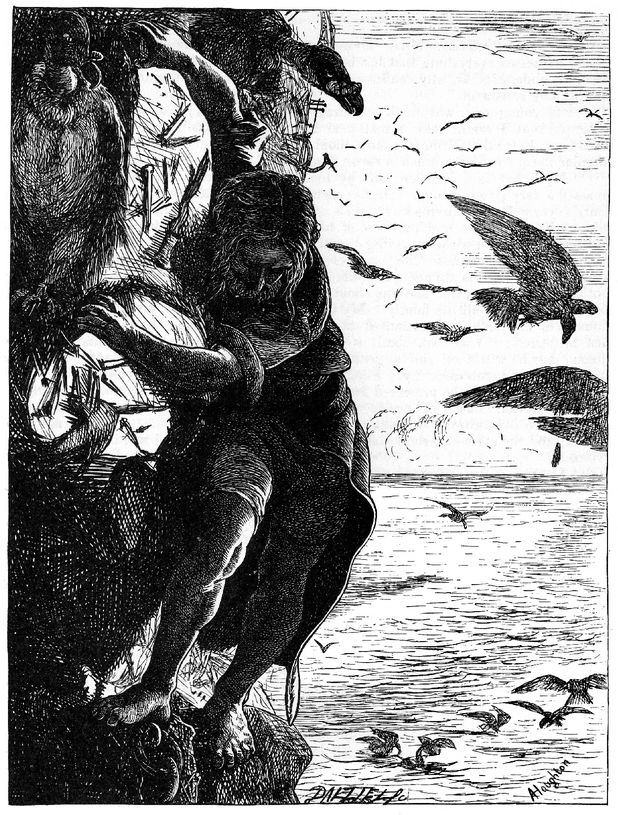

“The next morning we distinctly perceived the black mountain, and the idea we had formed of it made it appear still more dreadful and rugged than it really was. About midday we found ourselves so near it that we began to experience what the pilot had foretold. We saw the nails, and every other piece of iron belonging to the vessel, fly towards the mountain, against which they struck with a horrible noise, impelled by the violence of the magnetic attraction. The vessels then immediately fell to pieces, and sank to the bottom of the sea, which was so deep in this place that we could never discover the bottom by sounding. All my people perished; but Allah had pity upon me, and suffered me to save myself by clinging to a plank, which was driven by the wind directly to the foot of the mountain. I did not sustain the least injury, and had the good fortune to land near a flight of steps, which led to the summit of the mountain. I was much rejoiced at sight of these steps, for there was not the least vestige of land, either to the right or left, upon which I could have set my foot to save my life. I returned thanks to Allah, and invoking his holy name, began to ascend the mountain. The path was narrow, and so steep and difficult, that had the wind been at all violent I must have been blown into the sea. At last I reached the summit without any accident; and entering the dome, I prostrated myself on the ground, and offered my thanks to Heaven for the favour it had shown me.

“I passed the night under this dome, and while I was asleep, a venerable old man appeared to me, and said: ‘Agib, attend! When you wake, dig up the earth under your feet, and you will find a brazen bow with three leaden arrows, manufactured under certain stars to deliver mankind from many evils, which continually menace them. Shoot these three arrows at the statue; the man will be precipitated into the sea, and the horse will fall at your feet. You must bury the horse in the same spot from whence you take the bow and arrows. When you have done this the sea will begin to be agitated, and will rise as high as the foot of the dome at the top of the mountain. When it shall have risen thus high, you will see a boat come towards the shore, with only one man in it, holding an oar in each hand. This man will be of brass, but different from the statue that was overthrown. Embark with him without pronouncing the name of Allah, and let him be your guide. In ten days he will have carried you into another sea, where you will find the means of returning to your own country in safety; provided, as I have already said, you forbear from mentioning the name of Allah during the whole of your voyage.’

“Thus spake the old man. As soon as I was awake, I got up much consoled by this vision, and did not fail to do as the old man had directed me. I disinterred the bow and the arrows, and shot at the statue. With the third arrow I overthrew the rider, who fell into the sea, while the horse came crashing down to my feet. I buried it in the place where I had found the bow and arrows; and while I was doing this, the sea rose by degrees, till it reached the foot of the dome on the summit of the mountain. I perceived a boat at a distance, coming towards me. I offered my thankful prayers to Allah at thus seeing my dream in every respect fulfilled. The vessel at length approached the land, and I saw in it a man made of brass, as had been described. I embarked, and took particular care not to pronounce the name of Allah. I did not even utter a single word. When I had taken my seat, the brazen figure began to row from the mountain. He continued to work without intermission till the ninth day, when I saw some islands, which made me hope I should soon be free from every danger. The excess of my joy made me forget the direction the old man had given me in my dream: ‘Blessed be Allah!’ I cried out—‘Allah be praised!’

I had hardly pronounced these words, when the boat and the brazen man sank to the bottom of the sea. I remained in the water, and swam during the rest of the day towards the nearest island. The night which came on was exceedingly dark; and as I no longer knew where I was, I continued swimming at a venture. My strength was at last quite exhausted, and I began to despair of being able to save myself. The wind had much increased, and a mountainous wave threw me upon a flat, shallow shore, and retiring, left me there. I immediately made haste to get farther on land, for fear another wave should come and carry me back. The first thing I then did was to undress and wring the water out of my clothes; and I spread them upon the sand, which was still warm from the heat of the preceding day.

“The next morning, as soon as the sun had quite dried my garment, I put it on, and began to wander on the shore, trying to discover where I was. I had not walked far before I found my place of refuge to be a small desert island, very pleasant to look upon, and containing many sorts of fruit-trees, as well as others; but I observed that it was at a considerable distance from the mainland; and this rather lessened the joy I felt at having escaped from the sea. I nevertheless trusted in Heaven to dispose of my fate according to its will. Soon afterwards I discovered a very small vessel, which seemed to come full-sail directly from the mainland, with her prow towards the island where I was. As I had no doubt the crew were coming to anchor here, and as I knew not what sort of people they might be, whether friends or enemies, I determined not to show myself at first. I therefore climbed into a very thick tree, from whence I could examine the newcomers in safety. The vessel soon sailed up a small creek or bay, where ten slaves landed, with a spade and other implements in their hands, for digging up the earth. They went towards the middle of the island, where I observed them stop, and turn up the earth for some time; and, judging by their movements, I concluded they were lifting up a trap door. They immediately returned to the vessel, from which they landed many sorts of provisions and furniture; and each taking a load, they carried them to the place where they had before dug up the ground. They then seemed to descend, and I conjectured there was a subterraneous building. I saw them once more go to the vessel and come back with an old man, who brought with him a youth of comely appearance, about fourteen or fifteen years old. They all descended at the spot where the trap-door had been lifted up. When they came out again they shut down the door, and covered it with earth as before; then they returned to the creek where their vessel lay; but I observed that the young man did not come back with them. From this I concluded that they had left him in the subterraneous dwelling. This circumstance very much excited my astonishment.

“The old man and the slaves then embarked, and hoisting the sails, bore away for the mainland. When I found the vessel so far distant that I could not be perceived by the crew, I came down from the tree, and went directly to the place where I had seen the men dig away the earth. I now worked as they had done, and at last discovered a stone, two or three feet square. I lifted it up, and found that it concealed the entrance to a flight of stone stairs. I descended, and found myself in a large chamber, the floor of which was covered with a carpet. Here were also a sofa and some cushions covered with a rich stuff, and on the sofa sat a young man with a fan in his hand. I perceived all these things by the light of two torches, and also noticed fruits and pots of flowers, which were near him. At the sight of me the young man was much alarmed, but to give him courage, I said to him on entering, ‘Whoever you are, fear nothing. A King, and the son of a King, I have no intention of doing you any injury. On the contrary, you may esteem it a most fortunate circumstance that I am come here to deliver you from this tomb, where you seem to me to have been buried alive, though I am at a loss to conjecture the reason. What, however, most embarrasses me—for I will not deny that I have witnessed everything that has happened since you landed on this island—and what I cannot understand is, why you have suffered yourself to have been buried here, without making any resistance.’

“The young man was much encouraged by this speech; and with a polite gesture requested that I would take a seat near him. As soon as I had complied with his invitation, he said, ‘Prince, I am about to inform you of a circumstance, whose singular nature will very much surprise you.

“ ‘My father is a jeweller; and by his industry and skill in his profession, he has amassed a very large fortune. He has a great number of slaves and factors, who make many voyages for him in his own vessels. He has also correspondents in many courts, who are his customers, and purchase of him precious stones and jewels. He had been married a long time without having any children, when one night he dreamed that he should have a son, whose life however would be but short. When he awoke, the remembrance of this dream gave him much uneasiness. Some time after this, my mother informed him that she was about to give him an heir. In due time I was born, to the great joy of all the family. My father observed with the greatest exactness the moment of my birth, and consulted the astrologers concerning my destiny. The wise men answered: “Your son shall live without any accident or misfortune till he is fifteen; but he will then run a great risk of losing his life, and will not escape this danger without much difficulty. Should he be fortunate enough to come safely out of this peril, his life will be preserved for many years. About this time, too,” they added, “the equestrian statue of brass, which stands on the top of the loadstone mountain, will be overthrown by Prince Agib, the son of King Cassib, and will fall into the sea; and the stars also show that fifty days afterwards your son will be killed by that Prince.”

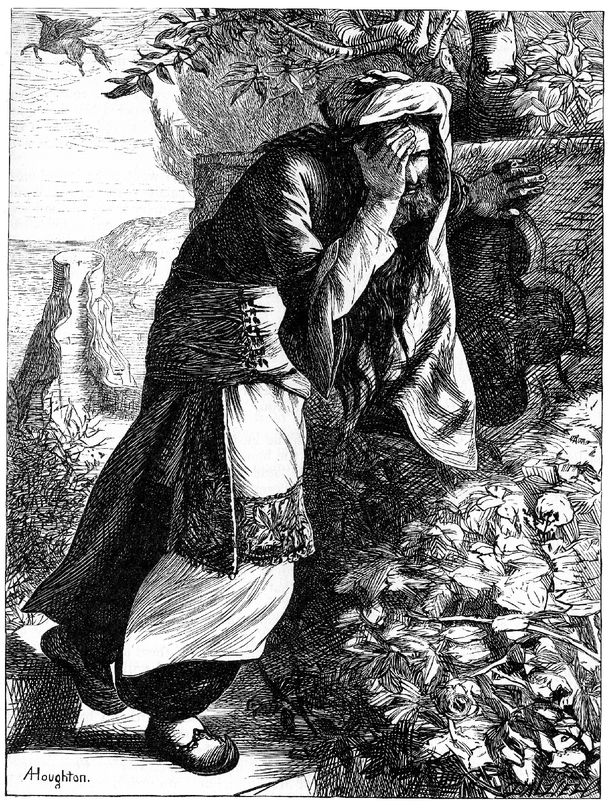

Agib ascending the loadstone rock.

“ ‘As this prediction agreed with my father’s dream, it caused him great anxiety and sorrow. Still he did not omit to bestow every care on my education, and continued to do so till now, when I am in the fifteenth year of my age. He was yesterday informed that ten days ago the brazen figure was overthrown by the Prince, whom I mentioned to you; and this intelligence gave him such alarm, and cost him so many tears, that he hardly looks like the man he was before.

“ ‘Since first he heard this prediction of the astrologers, my father has tried every means to frustrate my horoscope, and preserve my life. Long since he took the precaution to have this habitation built, in order to conceal me for the fifty days, directly he should learn that the statue had been overthrown. . . . It was on this account that, as soon as he knew what had happened ten days since, he came here for the purpose of concealing me during the forty days that remain; and he has promised, at the expiration of that time, to come and take me back. As for myself,’ added the youth, ‘I have the greatest hopes; for I do not believe that Prince Agib will come and look for me underground, in the midst of a desert island. This, my lord, is all I have to tell you.’

“While the son of the jeweller was relating his history to me, I inwardly laughed at those astrologers, who had predicted that I should take away his life; and I felt myself so very unlikely to verify their prediction, that directly he had finished speaking, I exclaimed with transport: ‘Oh, dear youth, put thy trust in the goodness of Allah, and fear nothing. Esteem this confinement only as a debt you had to pay, and from which from this hour you are free. I am delighted at my own good fortune in being cast away here, after suffering shipwreck, that I may guard you against those who would attempt your life. I will not quit you for a moment during the forty days which the vain and absurd conjectures of the astrologers have caused to appear as a time of peril. During this time, I will render you every service in my power, and afterwards I will, with your father’s permission and yours, take the opportunity of embarking in your vessel, in order to return to the continent; and when I am at home in my own kingdom, I shall never forget the obligation I am under to you, and will endeavour to prove my gratitude by every means in my power.’

“I encouraged him by this discourse, and thus gained his confidence. Fearful of alarming him, I took care to conceal from him the fact that I was the very person whom he dreaded; nor did I give him the least suspicion of the truth. We conversed about various things till night; and I easily discovered that the young man possessed a sensible and well-informed mind. We ate together of his store of provisions, which was so abundant that it would have lasted more than the forty days had there been other guests beside myself. We continued to converse together for some time after supper, and then retired to rest.

“When the youth got up the next morning, I presented him with a basin and some water. He washed himself, while I prepared the dinner, which I served up at the proper time. After our repast, I invented a sort of game, which was to amuse us, not only during the day, but for those that followed. I prepared the supper in the same way I had done the dinner; we then supped and retired to rest, as on the preceding day.

“We had sufficient opportunity to contract a friendship for each other. I perceived that he had an inclination for me; and on my side, the regard I felt for him was so strong, that I often said to myself, ‘The astrologers, who have predicted to the father that his son should be slain by my hands, were impostors, for it is impossible I can ever commit so horrid a crime.’ In short, we passed thirty-nine days in the pleasantest manner possible in this subterraneous habitation.

“At length, the fortieth morning arrived. The youth, when he was getting up, said to me, in a transport of joy which he could not restrain: ‘Be- hold me now, Prince, on the fortieth day; and, thanks to Allah and your good company, I am not dead. My father will not fail very soon to acknowledge his obligation, and furnish you with every means and opportunity that you may return to your kingdom. But while we are waiting,’ added he, ‘I beg of you to have the goodness to warm some water, that I may enjoy a thorough bath. I wish to prepare myself and change my dress, in order to receive my father with the greater respect.’ I put the water on the fire, and when it was sufficiently warm, I filled the bath. The youth stepped in: I washed and rubbed him myself. He then got out, and went into the bed I had prepared for him, and I threw the cover over him. After he had reposed himself, and slept for some time, he said to me: ‘O Prince, do me the favour to bring me a melon and some sugar; I want to eat something to refresh me.’

“I chose one of the melons which remained, and put it on a plate; and as I could not find a knife to cut it, I asked the youth if he knew where I should look for one. ‘There is one,’ he replied, ‘upon the cornice over my head.’ I looked up and perceived one there, but I over-reached myself in endeavouring to get it; and at the very moment I had it in my hand, my foot by some means got so entangled in the covering of the bed, that I unfortunately fell down on the young man, and pierced him to the heart with the knife. In an instant he was dead.

“At this sight I wept most bitterly. I beat my head and breast, I tore my habit, and threw myself on the ground in grief and despair. ‘Alas!’ I cried, ‘only a few hours more, and he would have been free from the danger against which he sought an asylum; and at the very moment when I thought the peril past, I am become the assassin, and have myself fulfilled the prediction. But I ask thy pardon, O Lord,’ I added, raising my head and hands towards heaven; ‘and if I am guilty of his death, I desire to live no longer.’

“After this misfortune, death would have been very acceptable to me, and I should have met it without dread. But we are seldom afflicted with evil, or blessed with good fortune, at the very moment we may desire either.

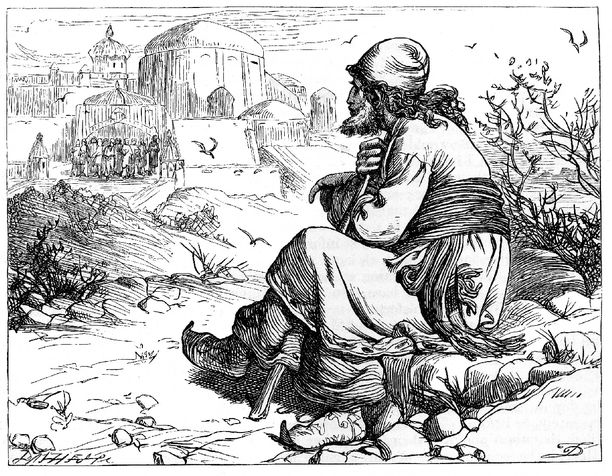

“Remembering after a time that all my tears and sorrow could not restore the youth to life, and that, as the forty days were now concluded, I should be surprised by the father, I went out of the subterraneous dwelling, and ascended to the top of the stairs. I replaced the large stone over the entrance, and covered it with earth. Scarcely had I finished my task when, looking towards the mainland, I perceived the vessel which was coming for the young man. Meditating what plan I should pursue, I said to myself: ‘If I let them see me, the old man will probably seize me, and order his slaves to kill me, when he discovers that his son has been murdered. Whatever I could allege in my own justification would never persuade him of my innocence. It is surely better, then, to withdraw myself from his sight, while I have the power, rather than expose myself to his resentment.’

“Near the subterraneous cavern there was a large tree, the thick foliage of which seemed to me to offer a secure retreat. I immediately climbed into this tree, and had hardly placed myself so as not to be seen, when I observed the vessel come to land in the same place where it had before anchored. The old man and the slaves instantly came on shore, and approached the subterraneous dwelling in a manner that showed they had some hopes of a good result. But when they saw that the ground had been lately disturbed, they changed colour, especially the old man. They then lifted up the stone, and descended the stairs. They called the young man by his name, but no answer was returned. This redoubled their anxiety. They sought him, and at last found him stretched on his couch with the knife through his heart, for I had not had the courage to draw it out. At this mournful sight, they uttered such lamentable cries that my tears flowed afresh. The old man fainted with horror. The slaves brought him out in their arms that he might feel the air, and placed him at the foot of the very tree in which I was. Notwithstanding all their efforts to recover him, the unfortunate father remained so long in an insensible state, that they more than once despaired of his life.

“He at length recovered from this long fainting-fit. The slaves then went down and brought up the body of his son, clothed in the poor youth’s finest garments; and as soon as the grave which they made was ready, they put the body in. Supported by two slaves, with his face bathed in tears, the old man threw in the first piece of earth, and then the slaves filled up the grave. This melancholy duty done, the furniture and remainder of the provisions were put on board the vessel. The old man, overcome with sorrow, and unable to walk alone, was carried to the vessel in a sort of litter by the slaves; and they immediately put to sea. They were soon at a considerable distance from the island, and I lost sight of them.

“I now remained alone in the island, and passed the following night in the subterraneous dwelling, which had not been again shut up; and the next day I took a survey of the whole island, resting in the pleasantest spots whenever I felt weary. I passed a whole month in this solitary manner. At the end of that time I perceived that the sea retired considerably, that the island appeared to become larger, and that the distance from the mainland visibly decreased. In truth, the water narrowed so much that there was now only a small channel between me and the continent, and I passed over to the mainland without going deeper than the middle of my leg. I then walked so far on the flat sand, that I was greatly fatigued. At last I reached firmer ground, and had left the sea at a considerable distance behind me, when I saw in the distance something that appeared like a large fire. At this I was much rejoiced; ‘for here,’ said I to myself, ‘I shall certainly find some people, as a fire cannot light itself.’ But as I came nearer I found myself mistaken in my conjecture, and discovered that what I had taken for a fire was a sort of castle of red copper, from which the rays of the sun were reflected in such a manner that it seemed all flames.

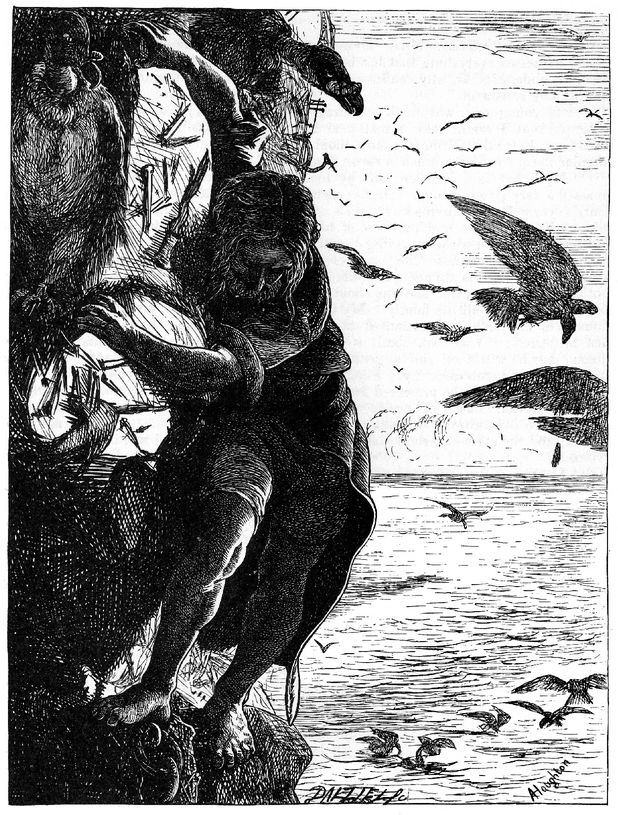

“I stopped near this castle, and sat down—partly to admire the beauty of the building, and partly to rest myself. I had not yet become tired of contemplating this magnificent house, when I perceived ten handsome young men, who came out, as it appeared to me, for the purpose of walking; but it struck me as a very surprising circumstance, that they were all blind of the right eye. An old man, of rather tall stature and very venerable appearance, accompanied them.

“I was very much astonished at meeting, at one time, so many people who were all not only blind of one but the same eye. While I was endeavouring to conjecture, in my own mind, for what purpose or by what accident they were thus collected together, they accosted me, and showed signs of great joy at my appearance. After the first greetings had passed, they inquired of me what brought me there: I told them that my history was rather long, but added that, if they would take the trouble to sit down, I would afford them the satisfaction they wished, by telling my adventures. They seated themselves, and I related to them everything that had happened to me, from the moment I had left my own kingdom till that instant. This narration greatly excited their surprise. When I had finished my story, they entreated me to come with them into the castle. I accepted their offer, and we entered the building together. After passing through a long suite of halls, antechambers, saloons, and cabinets, all very handsomely furnished, we came at length to a large and magnificent apartment, where there were ten small blue sofas, placed in a circle, but separate from each other. These served both as seats for repose during the day, and also as beds to sleep upon in the night. In the midst of this circle there was another sofa, less raised than the others, but of the same colour, upon which sat the old man of whom I have spoken, while the young men seated themselves upon the surrounding ten. As each sofa held only one person, one of the young men said to me, ‘Friend, sit down upon the carpet in the centre of this room, and seek not to know anything that regards us, nor the reason why we are all blind of the right eye; be satisfied with what you see, and do not seek to gratify any curiosity you may feel.’ The old man did not remain long seated; he rose presently and went out, but very soon returned, bringing with him a supper for the ten young men, to each of whom he distributed a certain portion. He gave me mine in the same way, and, like the rest, I ate my share apart. As soon as this repast was finished, the old man presented to each of us a cup of wine.

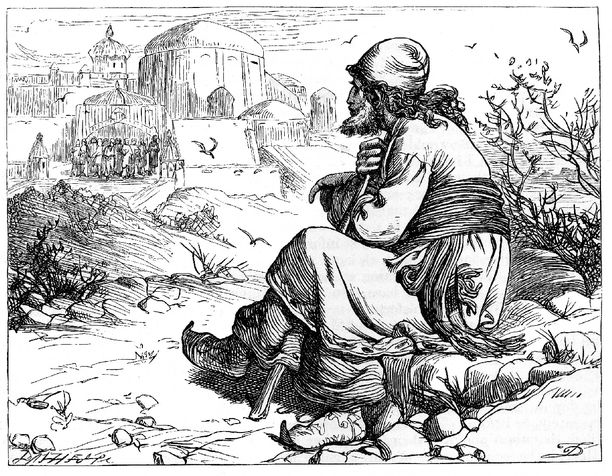

Agib contemplating the castle of copper.

“My history appeared to these men so extraordinary, that they made me repeat it when supper was over. This afterwards led to a conversation, which lasted the greater part of the night. One of the young men now observed that it was late, and said to the old one, ‘You see that it is time to retire to rest, and yet you do not bring us what we require for the discharge of our duty.’ At this the old man got up and went into a cabinet, from whence he brought upon his head, one after the other, ten basins, all covered with blue stuff; he placed one of these, with a torch, before each of the young men. They uncovered their basins, which contained some ashes, some charcoal in powder, and some lampblack. They mixed all these ingredients together, and began to rub them over their faces and smear their countenances, until their appearance was very frightful. After they had blacked themselves over in this manner, they began to weep, to make great lamentations, and to beat themselves on the head and breast, while they cried out continually: ‘Behold the consequences of our idleness and debauchery!’

“They passed almost the whole night in this strange occupation; at last they ceased their lamentations, and the old man brought them some water, in which they washed their faces and hands. They then took off their dresses, which were much torn, and put on others, and no one would have supposed they had been engaged in the extraordinary proceedings which I had witnessed. Judge what were my feelings during all this period. I was tempted a thousand times to break the silence which they had imposed upon me, and to ask them questions; and very amazement prevented me from getting any rest during the remainder of the night.

“The following morning, as soon as we were up, we went out to take the air, and I then said to my companions, ‘I must inform you, gentlemen, that I retract the promise you extorted from me last night, as I can no longer observe it. You are wise men, and you have given me sufficient reason to believe that you possess an enlarged understanding; yet, at the same time, I have seen you do things which none but madmen would be guilty of. Whatever misfortune my inquiry may bring upon me, I cannot refrain from asking for what reason you daubed your faces with ashes, charcoal, and black paint, and how you have each lost an eye. There must be some very singular cause for all this; I entreat you, therefore, to satisfy my curiosity.’ Notwithstanding the urgency of my request, they only answered that I was inquiring about things that did not concern me, that I had no interest in their actions, and that I must remain content. We passed the day in converse upon different subjects, and, when night approached, we supped separately, as before. The old man again brought the blue basins, with the contents of which the others anointed themselves; they then wept, beat themselves, and exclaimed, ‘Behold the consequences of our idleness and debauchery!’ The next night, and on the third also, they did the same thing.

“I could at last no longer resist my curiosity, and I very seriously entreated them to satisfy me, or to inform me by what road I could return to my kingdom; for I told them it was impossible that I could remain any longer with them, and every night be witness to the extraordinary sight I beheld, if I was not permitted to know the causes that produced it. One of the young men thus answered me, in the name of the rest: ‘Do not be astonished at what we do in your presence; if we have not hitherto yielded to your entreaties, it has been entirely out of friendship for you, and to spare you the anguish of being yourself reduced to the state in which you see us. If you wish to share our unhappy fate you have only to speak, and we will tell you what you wish to know.’ I told them I was determined to be satisfied at all risks. ‘Once more,’ resumed the same young man who had before spoken, ‘we advise you to restrain your curiosity; for it will cost you the sight of your right eye.’ ‘I care not,’ I answered; ‘and I declare to you, that if this misfortune does happen, I shall not consider you as the cause of it, but shall lay the blame entirely on myself.’ Again he represented to me that, when I should have lost my eye, I must not expect to remain with them, even if I had thought of doing so; for their number was complete, and could not be increased. I told them that it would be a satisfaction to me to continue to dwell among such agreeable men as they appeared to be; but still, if a separation were necessary, I would submit to it; since, whatever might be the consequence, I was determined that my curiosity should be gratified.

“The ten young men, seeing that I was not to be shaken in my resolution, took a sheep and killed it: after they had taken off the skin, they gave me the knife they had made use of, and said, ‘Take this knife: it will serve you for an occasion that will presently arise. We are going to sew you up in this skin, in which you must be entirely concealed. We shall then retire, and leave you in this place. Soon afterwards a bird of most enormous size, which they call a roc,

k will appear in the air; and, taking you for a sheep, it will swoop down upon you, and lift you up to the clouds: but let not this alarm you. The bird will soon return with his prey towards the earth, and will lay you down on the top of a mountain. As soon as you feel yourself upon the ground, rip open the skin with the knife, and set yourself free. On seeing you the roc will be alarmed, and fly away, leaving you at liberty. Tarry not in that place, but go on until you arrive at a castle of enormous magnitude, entirely covered with plates of gold, set with large emeralds and other precious stones. Go to the gate, which is always open, and enter. All of us who are here have been in that castle; but we will tell you nothing of what we saw, nor will we relate what happened to us there, as you will learn everything yourself. The only thing we can tell you of is, that our sojourn in that palace cost each of us a right eye, and that the penance you have seen us perform we are obliged to undergo in consequence of our having been there. The particular history of each of us is full of wonderful adventures; it would make a large book—but we cannot now tell you more.’

“When the young man had finished speaking, I wrapped myself up in the sheepskin, and took the knife which they gave me. After they had taken the trouble to sew me up in the skin they left me, and retired into their apartment. It was not long before the roc which they had mentioned made its appearance. It swooped down upon me, took me up in its talons as if I were a sheep, and carried me to the summit of a mountain. When I perceived that I was upon the ground, I did not fail to make use of my knife. I ripped open the skin, threw it off, and appeared before the roc, which flew away the instant it saw me. This roc is a white bird, of enormous size. Its strength is such, that it can lift up elephants from the ground and carry them to the top of mountains, where it devours them.

“My impatience to arrive at the castle was such, that I lost not an instant in proceeding thither. Indeed, I made so much haste that I reached it in less than half a day; and I may add, that I found it much more magnificent than it had been described. The gate was open, and I entered a square court of vast extent. It contained ninety-nine doors, made of sandalwood and that of the aloe-tree, and one (the hundredth) door was of gold. Besides all these, there were entrances to many magnificent stair-cases, which led to the upper apartments, and some others which I did not then see. The hundred doors I have mentioned formed the entrances either into gardens, or into storerooms filled with riches, or into some other apartments which contained objects most surprising to behold.

“Opposite to me I saw an open door, through which I entered into a large saloon, where forty young ladies were sitting. Their beauty was so perfect that the imagination cannot conceive anything beyond it. They were all very magnificently dressed; and as soon as they perceived me they rose, and without waiting for my salutation they called out, with an appearance of joy, ‘Welcome, my brave lord, you are welcome!’ And one of them, speaking for the rest, said, ‘We have a long time expected a person like you. Your manner sufficiently shows that you possess all the good qualities we could wish; and we hope that you will not find our company disagreeable or unworthy of you.’ After much resistance on my part, they persuaded me to sit down on a seat more raised than those on which they sat; and when I showed embarrassment at this distinction, they said, ‘It is your right: from this moment you are our lord, our master, and our judge; we are your slaves, and ready to obey your commands.’ Nothing in the world could have astonished me more than the desire and eagerness these ladies professed to render me every possible service. One brought me warm water to wash my feet; another poured perfumed water over my hands; some came with a complete change of apparel for me: some of the ladies served up a delicious repast, while others stood before me with glasses in their hands, ready to pour out the most delicious wine. Everything was done without confusion, and in such admirable order and such a pleasant way, that I was quite charmed. I ate and drank; and when I had finished, all the ladies placed themselves around me, and asked me to relate the circumstances of my journey. I gave them so full an account of my adventures that my story lasted till nightfall. Then some of the forty ladies who were seated nearest to me stayed to converse with me, while others, observing it was night, went out to seek for lights. They returned with a prodigious number, that produced almost the brilliance of day; but they were arranged with so much symmetry and taste, that we could hardly wish for the return of daylight.

“Some of the ladies covered the tables with dried fruits and sweetmeats of every kind; they also furnished the sideboard with many sorts of wine and sherbet, while others of the ladies came with several musical instruments. When everything was ready, they invited me to sit down to table; the ladies bore me company, and we remained there a considerable time. Those who entertained us with music sang to the sound of their instruments, thus producing a delightful concert. The rest began to dance, moving in pairs, one after the other, in the most graceful and elegant manner possible. It was past midnight before all these amusements were concluded. One of the ladies then, addressing me, said, ‘You are fatigued with the distance you have come to-day, and it is time you should take some repose. Your apartment is prepared,’ and they conducted me to a magnificent apartment. The other ladies then left me there and retired.

“I had hardly finished dressing myself in the morning, before the ladies came to my apartment. They were as splendidly adorned as on the preceeding day. They saluted me, and conducted me to a bath, but in a different manner; and when I had bathed, they brought me another dress, still more magnificent than the first. In short, Madam, not to tire you by repeating the same thing over again, I may tell you at once that I passed a whole year with these forty ladies, and that during the whole of the time the pleasures of the life I led were not marred by the least uneasiness or disquietude.

“I was therefore greatly surprised when, at the end of the year, the forty ladies, instead of presenting themselves to me in their accustomed good spirits, one morning entered my apartment with their countenances bathed in tears. Each of them came and embraced me, and said, ‘Adieu, dear prince, adieu; we are now compelled to leave you!’

“Their tears affected me deeply. I entreated to know the cause of their grief, and why they were obliged to leave me. ‘In the name of Allah, ye beautiful ladies,’ I exclaimed, ‘tell me, I beseech you, is it in my power to console you, or will my aid and assistance prove useless?’ Instead of answering my question directly, they said, ‘Would to God we had never seen or known you! Many men have done us the honour of visiting us before you came; but no one possessed the elegance, the gentleness, the power of pleasing, the merit we find in you; nor do we know how we shall be able to live without you.’ And as they said this their tears flowed afresh. ‘Amiable ladies,’ I cried, ‘do not, I beg of you, keep me any longer in suspense, but tell me the cause of your sorrow?’ ‘Alas!’ answered they, ‘what can it be that afflicts us but the necessity of separating from you? Perhaps we shall never meet again. Yet still, if you really wish it, and have sufficient command over yourself to observe the conditions, it is not absolutely impossible we may return to you.’ ‘In truth, ladies,’ I replied, ‘I do not at all understand what you mean; I conjure you to speak more openly!’ ‘Well, then, said one of them, ‘to satisfy you, we must inform you we are all Princesses, and the daughters of Kings. You have seen what manner of life we lead here; but at the end of each year we are compelled to absent ourselves for forty days, to fulfil some duties which may not be left undone, but the nature of which we are not at liberty to reveal; after this period we again return to this castle. Yesterday the year ended, and to-day we must leave you. This is the great cause of our affliction. Before we go, we will give you the keys of the whole palace, and particularly of the hundred doors, within which you will find ample room to gratify your curiosity and amuse your solitude during our absence. But, for your own sake, and for our particular interest, we entreat you to keep away from the golden door. If you open it we shall never see you again; and the fear we are in lest you should, increases our sorrow. We hope you will profit by the advice we have given you. Your repose, your happiness, nay your life, depends upon it; therefore be careful. If you indiscreetly yield to your curiosity, you will also do us much injury. We conjure you, therefore, not to be guilty of this fault, but to let us have the joy of finding you here at the end of the forty days. We would take the key of the golden door with us, but it would be an offence to a prince like yourself to doubt your circumspection and discretion.’

“At this speech I was greatly affected. I made them understand that their absence would cause me much pain, and thanked them very much for the good advice they gave me. I assured them I would profit by it, and would perform things much more difficult, if any sacrifice might procure me the happiness of passing the remainder of my life with ladies of such rare and extraordinary merit. We took a most tender leave of one another. I embraced them all; and they departed from the castle, in which I remained quite alone.

“The delight of their company, our sumptuous mode of life, and the concerts and various amusements with which the ladies had enlivened my stay, had so entirely engrossed my time during the year, that I had not had the least opportunity, nor indeed inclination, to examine the wonders of this enchanted palace. I had not even paid any attention to the multitude of extraordinary objects which were continually before my eyes; so much had I been enchanted by the charms and accomplishments of the ladies, and the pleasure I felt at finding them always employed in endeavouring to amuse me. I was very sorrowful at their departure; and although their absence was to last only forty days, the time during which I was to be deprived of their society, seemed to me an age.

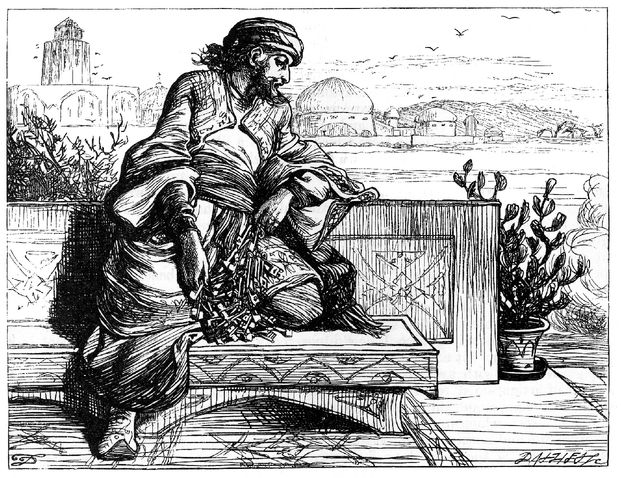

Agib.—“Left alone.”

“I determined, in my own mind, to observe the advice they had given me, not to open the golden door; but as I was permitted, with that one exception, to satisfy my curiosity, I took the keys belonging to the other apartments, which were regularly arranged, and opened the first door. I entered a fruit garden, to which I thought nothing in the world was comparable; not even that Paradise

l of which our religion promises us the enjoyment after death. The admirable order and arrangement, in which the trees were disposed, the abundance and variety of the fruits, many of which were of kinds unknown to me, together with their freshness and beauty, and the elegant neatness apparent in every spot, filled me with astonishment. Nor must I neglect to inform you, that this delightful garden was watered in a most singular manner: small channels, cut out with great art and regularity, and of different sizes, conveyed the water in great abundance to the roots of some trees which required a liberal supply to make them send forth their first leaves and flowers: while others, whose fruits were already set, received a smaller quantity of moisture; those whose fruit was much swelled had still less, while a fourth sort, on which the fruit had come to maturity, had just what was sufficient to ripen them. The size also, which all the fruits attained very much exceeded what we are accustomed to observe in our gardens. These channels that conducted the water to the trees on which the fruit was ripe, had barely enough water to preserve it in the same state without decaying it.

“I could not grow weary of examining and admiring this beautiful spot; I should never have left it if I had not, from this beginning, conceived a still higher idea of the things which I had not yet seen. I returned with my mind full of the wonders I had beheld. I then closed the first door, and opened the next.

“Instead of a fruit garden I now discovered a flower garden, which was not in its kind less singular. It contained a spacious parterre, not watered so abundantly as the first garden, but with greater skill and management, for each flower received just the amount of irrigation it required. The rose, the jessamine, the violet, the narcissus, the hyacinth, the anemone, the tulip, the ranunculus, the carnation, the lily, and an infinity of other flowers, which in other places bloom at various times, came all into flower at once in this spot; and nothing could be softer than the air in this garden.

“On opening the third door, I discovered a very large aviary. It was paved with marble of different colours, and of the finest and rarest sort. The cages were of sandal wood and aloes, and contained a great number of nightingales, goldfinches, canaries, larks, and other birds, whose notes were sweeter and more melodious than any I had ever heard. The vases which contained their food and water were of jasper, or of the most valuable agate. This aviary also was kept with the greatest neatness; and from its vast extent, I conceive that not less than a hundred persons would be necessary to maintain it in the perfection in which it appeared; and yet I could see no one, either here or in the other gardens, nor did I observe a single noxious weed, nor the least superfluous thing that could offend the sight.

“The sun had already set; and I retired much delighted with the warbling of the multitude of birds, which were flying about in search of commodious resting places where to perch and enjoy the repose of the night. I went back to my apartment, and determined to open all the other doors, except the hundredth, on the succeeding days. The next day I did not fail to go to the fourth door, and open it. But if the sights which I had seen on the foregoing days had surprised me, what I now beheld put me in ecstacy. I first entered a large court, surrounded by a building of a very singular sort of architecture, of which, to avoid being very prolix, I will not give you a description.

“This building had forty doors, all open. Each door was an entrance into a sort of treasury, containing more riches than many kingdoms. In the first room I found large quantities of pearls; and, what is almost incredible, the most valuable, which were as large as pigeons’ eggs, were more numerous than the smaller. The second was filled with diamonds, carbuncles, and rubies; the third with emeralds; the fourth contained gold in ingots; the fifth gold in money; the sixth ingots of silver; and the two following coined silver. The rest were filled with amethysts, chrysolites, topazes, opals, turquoises, jacinths, and every other sort of precious stone we are acquainted with—not to mention agate, jasper, cornelian, and coral, in branches and whole trees, with which one apartment was entirely filled. Struck with surprise and admiration at the sight of all these riches, I exclaimed, ‘It is impossible that all the treasures of every potentate in the universe, if they were collected in the same spot, can equal these! How happy am I in possessing all these treasures, and in sharing them with such amiable Princesses!’

“I will not detain you, Madam, by giving you an account of all the wonderful and valuable things which I saw on the following days; I will only inform you, that I spent nine and thirty days in opening the ninety-nine doors, and in admiring everything the rooms thus disclosed contained. There now remained only the hundredth door, which I was forbidden to touch. The fortieth day since the departure of the charming Princesses now arrived. If only for that one day, I had maintained the power over myself I ought to have had, I should have been the happiest instead of the most miserable of men. The Princesses would have returned the next day; and the pleasure I should have experienced in receiving them ought to have acted as a restraint upon my curiosity; but through a weakness, which I shall never cease to lament, I yielded to the temptation of some demon, who did not suffer me to rest till I had subjected myself to the pain and punishment I have since experienced.

“Though I had promised to restrain my curiosity, I opened the fatal door. Before I even set my foot within this room, a very agreeable odour struck me, but it was so powerful, it made me faint. I soon, however, recovered; but instead of profiting by the warning, instantly shutting the door, and giving up all idea of satisfying my curiosity, I persevered and entered—having first waited till the odour was lessened and dispersed through the air. I then felt no inconvenience from it. I found a very large vaulted room, the floor of which was strewn with saffron. It was illuminated by torches made of aloe-wood and ambergris, and placed on golden stands: these torches exhaled a strong perfume. The brightness caused by them was still further heightened by many lamps of silver and gold, which were filled with oil composed of many perfumes.

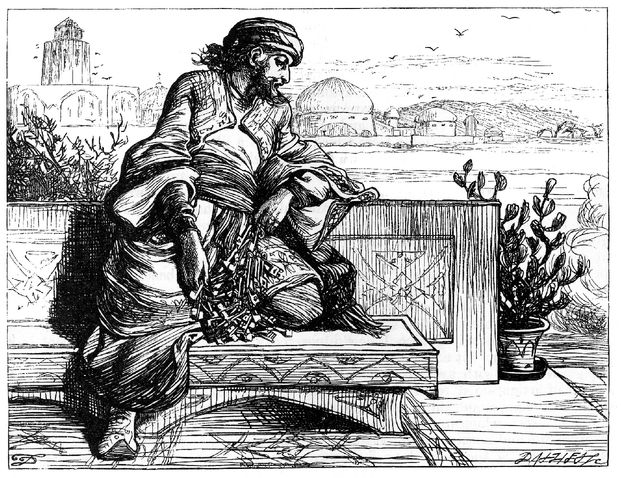

“Among the numerous objects which attracted my attention was a black horse, the best shaped and most beautiful that ever was seen. I went close to it, to observe it more attentively. It had a saddle and bridle of massive gold, richly worked. On one side of its manger there was clean barley and sesame, and the other was filled with rosewater. I took hold of the horse’s bridle, and led it towards the light, to examine it the better. I mounted it, and endeavoured to make it go; but as it would not move I struck it with a switch, which I had found in its magnificent stable. So soon as it had felt the stroke the horse began to neigh in a most dreadful manner; then spreading its wings, which I had not till that moment perceived, it rose so high in the air, that I lost sight of the ground. I now thought only of holding fast on its back; nor did I experience any injury, except the great terror with which I was seized. At length my steed began to descend towards the earth, and lighted upon the terraced roof of a castle; then, without giving me time to get down, it shook me so violently that I fell off behind, and with a blow of its tail it struck out my right eye.

“In this way I became blind; and the prediction of the ten young lords was now instantly brought to my recollection. The horse itself immediately spread its wings, took flight, and disappeared. I rose up, much afflicted at the misfortune which I had thus voluntarily brought upon myself. I traversed the whole terrace, keeping my hand up to my eye, as I felt very considerable pain from the stroke. I then went down, and came to a saloon, which I immediately recognized from observing ten sofas disposed in a circle, and a single one, less elevated, in the middle: it was, in fact, in the very castle whence I had been carried up by the roc.

“The ten young lords were not in the castle. I, however, waited, and it was not long before they came, accompanied by the old man. They did not seem at all astonished at seeing me, nor at observing that I had lost my right eye. ‘We are very sorry,’ they said, ‘we cannot congratulate you, on your return, in the manner we could have wished; but you know we were not the cause of your misfortune.’ ‘It would be,’ I replied, ‘very wrong in me to accuse you of it: I brought it entirely upon myself, and the fault lies with me alone.’ ‘If thy misfortune,’ answered they, ‘can derive any consolation from knowing that others are in the same situation, we can afford thee that satisfaction. Whatever may have happened to you, be assured we have experienced the same. Like yourself, we have enjoyed every species of pleasure for a whole year; and we should have continued in the enjoyment of the same happiness if we had not opened the golden door during the absence of the Princesses. You have not been more prudent than we were, and you have experienced the same punishment that has fallen upon us. We wish we could receive you into our society, to undergo the same penance we are performing, and of which we know not the duration; but we have before informed you of the circumstances which prevent us. You must, therefore, take your departure, and go to the Court of Baghdad, where you will meet with the person who will be able to decide your fate.’ They pointed out the road I was to follow; I then took my leave and departed.

Agib looses his eye.

“During my journey I shaved my beard and eyebrows, and put on the habit of a calender. I was a long time on the road, and it was only this evening that I arrived in this city. At one of the gates I encountered these two calenders, my brethren, who were equally strangers with myself. On thus accidentally meeting, we were all much surprised at the singular circumstance, that each of us had lost his right eye. We had not, however, much leisure to converse on the subject of our mutual misfortune. We had only time, Madam, to implore your assistance, which you have generously afforded us.

“When the third calender had finished the recital of his history, Zobeidè, addressing herself both to him and his brethren, said, ‘Depart! You are all three at liberty to go wherever you please.’ But one of the calenders answered, ‘We beg of you, Madam, to pardon our curiosity, and permit us to stay and hear the adventures of these guests, who have not yet spoken. The lady then turned to the side where sat the caliph, the vizier Giafar, and Mesrour, of whose real condition and character she was still ignorant, and desired each of them to relate his history.

“The grand vizier, Giafar, who was always prepared to speak, immediately answered Zobeidè. ‘We obey, Madam,’ said he; ‘but we have only to repeat to you what we already related before we entered. We are merchants of Moussoul, and we are come to Baghdad for the purpose of disposing of our merchandise, which we have placed in the warehouses belonging to the khan where we live. We dined to-day together, with many others of our profession, at a merchant’s of this city. Our host treated us with the most delicate viands and finest wines, and had moreover provided a company of male and female dancers, and a set of musicians, to sing and play. The great noise and uproar which we all made attracted the notice of the watch, who came and arrested many of the guests; but we had the good fortune to escape. As, however, it was very late, and the door of our khan would be shut, we knew not whither to go. It happened, accidentally, that we passed through your street; and as we heard the sounds of pleasure and gaiety within your walls, we determined to knock at the door. This is the only history we have to tell, and we have done according to your commands.’

“After listening to this narration, Zobeidè seemed to hesitate as to what she should say. The three calenders, observing her indecision, entreated her to be equally generous to the three pretended merchants of Moussoul as she had been to them. ‘Well then,’ she cried, ‘I will comply. I wish all of you to be under the same obligation to me. I will therefore do you this favour, but it is only on condition that you instantly quit this house, and go wherever you please.’ Zobeidè gave this order in a tone of voice that showed she meant to be obeyed: the caliph, the vizier, Mesrour, the three calenders, and the porter, therefore, went away without answering a word; for the presence of the seven armed slaves served to make them very respectful. So soon as they had left the house and the door had been closed behind them, the caliph said to the three calenders, without letting them know who he was, ‘Ye are strangers, and but just arrived in this city; what do you intend to do, and which way do you think of going, as it is not yet daylight?’ And they answered, ‘This very thing, sir, embarrasses us.’ ‘Follow us then,’ returned the caliph, ‘and we will relieve you from this difficulty.’ He then whispered his vizier, and ordered him to conduct them to his own house, and bring them to the palace in the morning. ‘I wish,’ added he, ‘to have their adventures written; for they are worthy of a place in the annals of my reign.’

“The vizier Giafar took the three calenders home; the porter went to his own house, and the caliph, accompanied by Mesrour, returned to his palace. He retired to his couch; but his mind was so entirely occupied by all the extraordinary things he had seen and heard, that he was unable to close his eyes. He was particularly anxious to know who Zobeidè was, and the motives she could possibly have for treating the two black dogs so ill, and also the reason that Aminè’s bosom was so covered with scars. The morning at length broke, while he was still engaged with these reflections. He immediately rose, and went into the council-chamber of the palace; he then gave audience, and seated himself on his throne.

“It was not long before the grand vizier arrived, and hastened to perform the customary obeisances. ‘Vizier,’ said the caliph to him, ‘the business which is now before us is not very pressing; that of the three ladies and the two black dogs is of more consequence; and my mind will not be at rest till I am fully informed of everything that has caused me so much astonishment. Go, and order these ladies to attend; and at the same time bring back the three calenders with you. Hasten, and remember I am impatient for your return.’

“The vizier, who was well acquainted with the hasty and passionate disposition of his master, hurried to obey him. He arrived at the house of the ladies, and, with as much politeness as possible, informed them of the orders he had received to conduct them to the caliph; but he made no reference to the events of the night before.

“The ladies immediately put on their veils, and went with the vizier, who, as he passed his own door, called for the calenders. They had just learnt that they had already seen the caliph, and had even spoken to him without even knowing it was he. The vizier brought them all to the palace; he had executed his commission with so much diligence that his master was perfectly satisfied. The caliph ordered the ladies to stand behind the doorway which led to his own apartment, that he might preserve a certain decorum before the officers of his household. He kept the three calenders near him; and these men made it sufficiently apparent, by their respectful behaviour, that they were not ignorant in whose presence they had the honour to appear.

“When the ladies were seated, the caliph turned towards them and said, ‘When I inform you, ladies, that I introduced myself to you last night, disguised as a merchant, I shall, without doubt, cause you some alarm. You are afraid, probably, that you offended me, and you think, perhaps, that I have ordered you to come here—only to show you some marks of my resentment; but be of good courage, be assured that I have forgotten what is past, and that I am even very well satisfied with your conduct. I wish that all the ladies of Baghdad possessed as much sense as I have observed in you. I shall always remember the moderation with which you behaved after the incivility we were guilty of towards you. I was then only a merchant of Moussoul, but I am now Haroun Alraschid, the Seventh Caliph of the glorious House of Abbas, which holds the place of our Great Prophet. I have ordered you to appear here, only that I may be informed who you are, and to learn the reason why one of you, after having ill-treated the two black dogs, wept with them: nor am I less curious to hear how the bosom of another became so covered with scars.’

“Though the caliph pronounced these words very distinctly, and the three ladies understood them very well, the vizier Giafar did not fail to repeat them, according to custom. The prince had no sooner encouraged Zobeidè by this speech, which he addressed to her, than she gave him the satisfaction he required.

“Commander of the Faithful!—The history, which I am going to relate to your Majesty, is probably one of the most surprising you have ever heard. The two black dogs and myself are three sisters, daughters of the same mother and father; and I shall, in the course of my narration, inform you by what strange accident my two sisters have been transformed into dogs. The two ladies, who live with me, and who are now here, are also my sisters, by the same father, but by a different mother. She whose bosom is covered with scars is called Aminè; the name of the other is Safiè, and I am called Zobeidè.

After both Zobeidè and Aminè had told their histories, a fairy summoned by the burning of two hairs restored the two dogs to their original form and cured Aminè of her scars and reunited her with her husband, the caliph’s eldest son, Prince Amin.

“Then it was that this great caliph, filled with wonder and astonishment, and well satisfied at the alterations and changes that he had been the means of effecting, performed some actions which will be eternally spoken of. He first of all summoned before him his son, Prince Amin, told him he was acquainted with the secret of his marriage, and informed him of the cause of the wound in Aminè’s cheek. The prince did not wait for his father’s command to reinstate his wife—he immediately became reconciled to her.

“The caliph next declared that he bestowed his heart and hand upon Zobeidè, and proposed her other three sisters to the calenders, the sons of kings, who joyfully accepted them for their wives. The caliph then assigned to each of the calender-princes a most magnificent palace in the city of Baghdad; he raised them to the first offices of the empire, and admitted them into his council. The principal cadi of Baghdad was summoned, and, with proper witnesses, drew up the forms of marriage; and in bestowing happiness on a number of persons who had experienced incredible misfortunes, the illustrious and magnificent Caliph Haroun Alraschid earned for himself a thousand benedictions.”