THE STORY TOLD BY THE JEWISH PHYSICIAN.

WHILE I was studying medicine at Damascus, and when I had even begun to practise that admirable science with considerable success, a slave one day came to inquire for me; and desired me to go to the house of the governor of the city, to visit a person who was ill. I accordingly went, and was introduced into a chamber, where I perceived a very handsome young man; but he seemed very much depressed, apparently from some pain he suffered. I saluted him, and went and sat down by his side. He returned no answer to my salutation, but showed me by a look that he understood me, and was grateful for my kindness. ‘Will you do me the favour, my friend,’ I said to him, ‘to put out your hand, that I may feel your pulse?’ Hereupon, instead of giving me his right hand as is the usual custom, he held out his left. This astonished me very much. ‘Surely,’ said I to myself, ‘it is a mark of great ignorance of the world not to know that it is the constant custom to present the right hand to a physician.’ I nevertheless felt his pulse, wrote a prescription, and then took my leave.

“I continued to visit him regularly for nine days; and every time that I wished to feel his pulse he still held out his left hand to me. On the tenth day he appeared to be so much recovered, that I told him he no longer required me, or indeed any medical help but the bath. The governor of Damascus was present; and, in order to prove how well he was satisfied with my abilities and conduct, he at once had me dressed in a very rich robe, and appointed me physician to the hospital of the city, and physician in ordinary to himself. He told me, moreover, that I should be always welcome to his house, where there was constantly a place provided at the table for me.

“The young man whom I had cured also gave me many proofs of his friendship, and requested me to accompany him to the bath. I complied; and when we had gone in and his slaves had undressed him, I perceived that he had lost his right hand. I even remarked that it had been lately cut off. This had been the real cause of his disease, which he had concealed from me; and, while the strongest applications had been secretly used to cure his arm as quickly as possible, his friends had only called me in to prevent any bad consequences arising from a fever which had come on. I was astonished and distressed to see him thus maimed. My countenance showed the sympathy I felt for him. The young man remarked it, and said to me: ‘Do not be surprised at seeing me without my right hand. I will one day inform you how I lost it; and you will hear a most wonderful and strange adventure.’

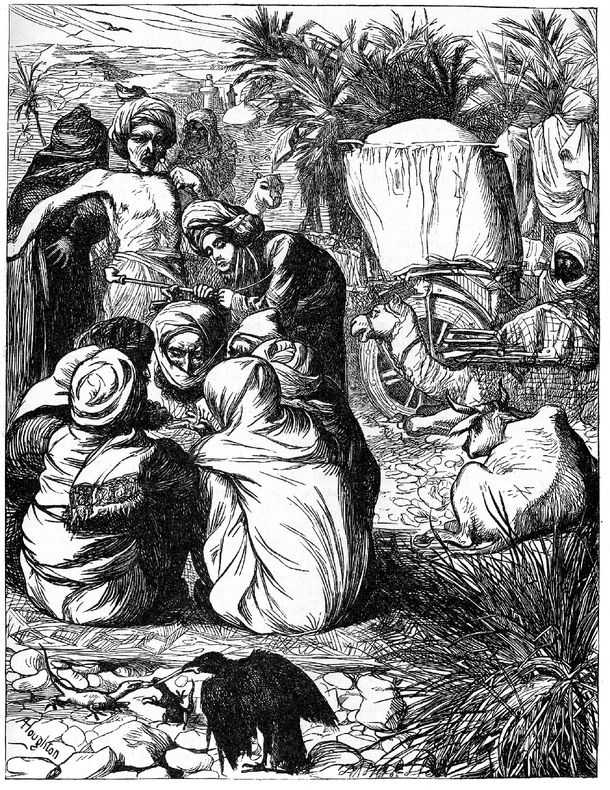

The travellers resting before Damascus.

“On our return from the bath, we sat down to table and began to converse. He asked me if he might safely take a walk out of the city to the garden of the governor. I replied that it would be very beneficial to him to go into the air. ‘Then,’ said he, ‘if you choose to accompany me, I will there relate my history.’ I told him I was at his service for the rest of the day. He immediately ordered his people to prepare a slight repast, and we set out for the garden of the governor. We walked two or three times round the enclosure, and then seated ourselves on a carpet, which his people spread under a tree that formed a delightful shade around. Then the young man began to tell his history in these words:—

“ ‘I was born at Moussoul, and am a member of one of the chief families in that city. My father was the eldest of ten children, who were all living and all married when my grandfather died. But among this number of brothers my father was the only one who had any children, and I was his only son. He took great care of my education, and had me taught everything which a boy in my station in life ought to be acquainted with.

“ ‘I was grown up, and had begun to associate with the world, when one Friday I went to the noonday prayers in the great mosque of Moussoul with my father and my uncles. After the prayers were over every one retired, except my father and my uncles, who seated themselves on the carpet which covered the whole floor of the mosque. I sat down with them; and, as we discoursed on various topics, the conversation happened to turn on travel. The beauties and peculiarities of various kingdoms, and of their principal towns, were discussed and praised. But one of my uncles said, that if the account of a great number of travellers might be believed, there was not in the world a more beautiful country than Egypt on the banks of the Nile, which all agreed in praising. What he related of this land gave me such an opinion of its beauties, that from that moment I formed the wish to travel thither. All that my other uncles could say in favour of Baghdad and the Tigris, when they vaunted Baghdad as the true abode of the Mussulman religion and the metropolis of all the cities in the world, did not make half so much impression on me. My father maintained the opinion of that brother who had spoken in favour of Egypt; and I was very glad of this. ‘Let people say what they will,’ cried he; ‘the man who has not seen Egypt has not seen the greatest wonder in the world! The earth in that country is all gold! I mean to say it is so fertile that it enriches the inhabitants like a golden soil. All the women enchant the beholder by their beauty or their agreeable manners. What river can be more delightful than the Nile? What stream rolls with water so pure and delicious? The residue that remains after its overflowings enriches the ground, and makes it produce without any trouble a thousand times more than other countries yield with all the labour that can be bestowed on their cultivation. Hear what a poet, who was obliged to quit Egypt, wrote to the natives of that country: “Your Nile heaps riches on you every day; it is for you alone that it travels so far. Alas! now that I must leave you, my tears will flow as abundantly as its waters! You will continue to enjoy its pleasures, whilst I, longing to partake of them, am condemned to exile!”

“ ‘If you cast your eyes on the island which is formed by the two largest branches of the Nile,’ continued my father, ‘what a variety of verdure will you behold! What a beautiful enamel of all kinds of flowers! What a prodigious number of cities, towns, canals, and a thousand other pleasing objects! If you turn on the other side, looking towards Ethiopia, how many different causes for admiration! I can only compare the verdure of all those meadows, watered by the various canals in the island, to the lustre of emeralds set in silver! Is not Cairo the largest, the richest, the most populous city in the universe? How magnificent the edifices, private and public! If you go to the pyramids you are lost in astonishment! You are struck speechless at the sight of those enormous masses of stone, whose lofty summits are lost in the clouds! You are forced to confess that the Pharaohs, who employed so many men and such immense riches in the construction of these gigantic monuments, surpassed in magnificence and invention all the monarchs who have succeeded them, not only in Egypt, but in the whole world! These monuments, which are so ancient that the learned are at a loss to fix the period of their erection, still brave the ravages of time, and will remain for ages. I say nothing of the maritime towns of the kingdom of Egypt, such as Damietta, Rosetta, and Alexandria, where so many nations traffic for various kinds of grain and stuffs, and a thousand other things for the comfort and pleasure of mankind. I speak of the country from my own knowledge: I spent some years of my youth there, which I shall ever esteem the happiest of my life.’

“ ‘In reply to my father, my uncles could but agree to all he had said about the Nile, Cairo, and the whole of the kingdom of Egypt. As for me, my imagination was so filled with it that I could not sleep all night. A short time afterwards my uncles also showed how much they had been struck with my father’s discourse. They all proposed to him a journey into Egypt. He acceded to the plan; and, as they were rich merchants, they resolved to take with them such goods as they might dispose of with profit. I heard of their preparations for the journey: I went to my father, with tears in my eyes, and entreated his permission to accompany them, with a stock of merchandise to sell on my own account. ‘You are too young,’ said he, ‘to undertake such a journey. The fatigue would be too much for you; moreover, I feel sure you would be a loser by your bargains.’ This rebuff did not diminish my desire to travel. I persuaded my uncles to intercede for me with my father; and they at length obtained his permission that I should go as far as Damascus, where they would leave me, whilst they continued their journey into Egypt. ‘The city of Damascus,’ said my father, ‘has its beauties; and he must be satisfied that I give him leave to go thus far.’ Much as I wished to see Egypt after the accounts I had heard, I was obliged to relinquish the thought; for my father had a right to my obedience, and I submitted to his will.

“ ‘I set off from Moussoul with my father and my uncles. We traversed Mesopotamia, crossed the Euphrates, and arrived at Aleppo, where we remained a few days. From thence we proceeded to Damascus, the first appearance of which agreeably surprised me. We all lodged in the same khan. I found the city large and well fortified, populous, and inhabited by civilized people. We passed some days in visiting the delightful gardens which beautify the suburbs, and we agreed that the report we had heard of Damascus was true—that it was in the midst of Paradise. After staying here some time, my uncles began to think of proceeding on their journey, having first taken care to dispose so advantageously of my merchandise, that I gained a large profit. This produced a considerable sum for me, with the possession of which I was quite delighted.

“ ‘My father and my uncle left me at Damascus, and continued their journey. After their departure I was very careful not to spend my money in extravagance. Still, I hired a magnificent house. It was built entirely of marble, and ornamented with paintings; and there was a garden attached to it, in which were some very fine fountains. I furnished the house, not indeed so expensively as the magnificence of the place required, but at least sufficiently for a young man of my condition. It had formerly belonged to one of the principal grandees of the city, named Modoun Ab dalraham, and it was now the property of a rich jeweller, to whom I paid only two scherifs

n a month for the use of it. I had a numerous retinue of servants, and lived in good style. I sometimes invited my acquaintances to dine with me, and frequented entertainments at their houses. Thus I passed my time at Damascus during the absence of my father. No grief or anxiety disturbed my repose, and to enjoy the society of agreeable people was my chief pleasure.

“ ‘One day, when I was sitting at the door of my house, a lady, handsomely dressed and of a good figure, came towards me, and asked me if I did not sell stuffs; and she immediately entered my house. Thereupon I rose and shut the door, and ushered her into a room, where I entreated her to be seated. ‘Lady,’ said I, ‘I have had some stuffs which were worthy of your notice, but it grieves me to say I have not any now.’ She took off the veil which concealed her face, and discovered to my eyes a countenance of remarkable beauty. ‘I do not want any stuffs,’ said she; ‘I come to see you, and to pass the evening in your company, if you approve of me.’

“ ‘Delighted with my good forture, I immediately gave my people orders to bring us several kinds of fruits and some bottles of wine. We sat down to table, and ate and drank and regaled ourselves till midnight; in short, I had never passed an evening so agreeably before. Before she left me, the lady put ten scherifs into my hand, saying, ‘I insist on your accepting this present from me; if you refuse I will never see you more.’ I dared not decline a gift thus pressed upon me; and the lady continued: ‘Expect me in three days, after sunset.’ She then took her leave, and I felt that she carried away my heart with her.

“ ‘At the expiration of three days, she returned at the appointed hour. I had expected her with impatience, and received her with joy. We passed the evening as agreeably as at our former meeting, and when she left me, again promising to return in three days, she obliged me, as before, to accept ten scherifs from her.

“ ‘On her third visit, when both of us were merry with wine, she said to me, ‘My dear friend, what do you think of me? Am I not handsome and pleasing?’ ‘O lady,’ replied I, ‘these questions are very useless; all the proofs of affection I give you ought to convince you I love you. You are my queen, my sultana; you form the sole happiness of my life.’ ‘Indeed,’ she resumed, ‘I am sure you would change your tone, if you were to see a friend of mine who is younger and handsomer than I am. She has such lively spirits, that she would make the most melancholy of men laugh. I must bring her to you. I have mentioned you to her, and have given her such an account that she is dying with impatience to see you. She begged me to procure her this pleasure, but I did not dare to comply with her request till I had mentioned it to you.’ ‘O lady,’ said I, ‘you must do according to your will; but in spite of all you say about your friend, I defy all her charms to captivate my heart, which is so devotedly yours that nothing can ever alter my attachment.’ ‘Beware of protestations,’ replied she. ‘I warn you that I am going to put your heart to a great trial.’

“ ‘We said no more at the time; but this time the lady gave me fifteen scherifs instead of ten at her departure. ‘Remember,’ said she, ‘that in two days a new guest will visit you. Prepare to give her a good reception. We shall come at the usual hour after sunset.’

“ ‘I had the room decorated, and prepared a sumptuous collation on the day when they were to come. I waited for them with great impatience. At length, when the evening was closing in, they came. They both unveiled; and if I had been surprised with the beauty of the first lady, I had much more reason to be astonished at the charms of her friend. Her features were regular and perfectly formed. She had a glowing complexion, and eyes of such brilliancy that I could scarcely bear their lustre. I thanked her for the honour she conferred on me, and entreated her to excuse me if I did not receive her in the style she deserved. ‘I ought to thank you,’ she replied, ‘for having allowed me to accompany my friend hither; but as you are so good as to allow me to remain, let us put aside all ceremony.’

“ ‘I had given orders for the collation to be served as soon as the ladies arrived; accordingly we sat down to table. I was opposite to my new guest, who did not cease to look smilingly at me. I could not resist her winning glances; and she quickly made herself mistress of my heart. But while she inspired me with love, she felt the flame herself; and far from practising any restraint, she said a number of tender things to me.

“ ‘The other lady, who observed us, at first only laughed. ‘I told you,’ said she, addressing herself to me, ‘that you would be charmed with my friend, and I perceive you have already become inconstant towards me.’ ‘Lady,’ replied I, laughing, ‘you would have reason to complain, if I were wanting in politeness towards a lady whom you love, and have done me the honour to bring here; both of you would reproach me if I failed in the duties of hospitality.’

“ ‘We continued feasting; but in proportion as we became heated with wine, the new lady and I exchanged compliments with so little precaution, that her friend conceived a violent jealousy, of which she soon gave us a fatal proof. She rose and went out, saying that she should soon return; but a few minutes afterwards, the lady who had remained with me changed countenance; she fell into strong convulsions, and expired in my arms, whilst I was calling my servants to my assistance. I went out immediately, and inquired for the other lady; my people told me that she had opened the street door, and had gone away. I then began to suspect, and indeed I had good reason to do so, that she had occasioned the death of her friend. In fact, she had had the cunning and the wickedness to put a strong poison into a cup of wine which she herself had presented to her.

“ ‘I was horror-struck at this terrible event. ‘What shall I do?’ said I to myself. ‘What will become of me?’ As I felt sure that I had no time to lose, I ordered my people to raise up by the light of the moon, and as quietly as possible, one of the largest slabs of the marble with which the court of my house was paved. They obeyed me, and dug a grave in which they interred the body of the young lady. After the marble was replaced, I put on a travelling dress; and, taking all the money I possessed, I locked up everything, even the door of my house, on which I put my own seal. I went to the jeweller who was the proprietor, paid him what I owed, and a year’s rent in advance besides. I gave him the key, and begged him to keep it for me. ‘A very important affair,’ said I, ‘obliges me to be absent for some time; I must go to visit my uncles at Cairo.’ I then took my leave of him, instantly mounted my horse, and set off with my people, who were waiting for me.

“ ‘My journey was prosperous, and I arrived at Cairo without any mishap. I found my uncles astonished to see me. I accounted for my coming by saying that I was tired of waiting for them; and that, receiving no intelligence of them, my uneasiness had induced me to undertake the journey. They received me very kindly, and promised to intercede with my father, that he might not be displeased at my quitting Damascus without his permission. I lodged in the same khan with them, and saw everything that was worth seeing in Cairo.

“ ‘As they had sold all their merchandise, they talked of returning to Moussoul, and were already beginning to make preparations for their departure; but as I had not seen all that I wished to see in Egypt, I left my uncles. I went to lodge in a quarter very distant from their khan, and did not make my appearance till they had set off. They sought me in the city for a considerable time; but failing to find me, they supposed that, displeased with myself at coming to Egypt against the will of my father, I had returned privately to Damascus; and they left Cairo in the hope of meeting me at Damascus, where I could join them and return home.

“ ‘I thus remained at Cairo after their departure, and lived there three years gratifying my curiosity and beholding all the wonders of Egypt. During that time I took care to send my rent to the jeweller; always desiring him to keep my house for me, as it was my intention to return to Damascus, and reside there for some years. I did not meet with any remarkable adventure at Cairo; but you will, no doubt, be very much surprised to hear what befel me on my return to Damascus.

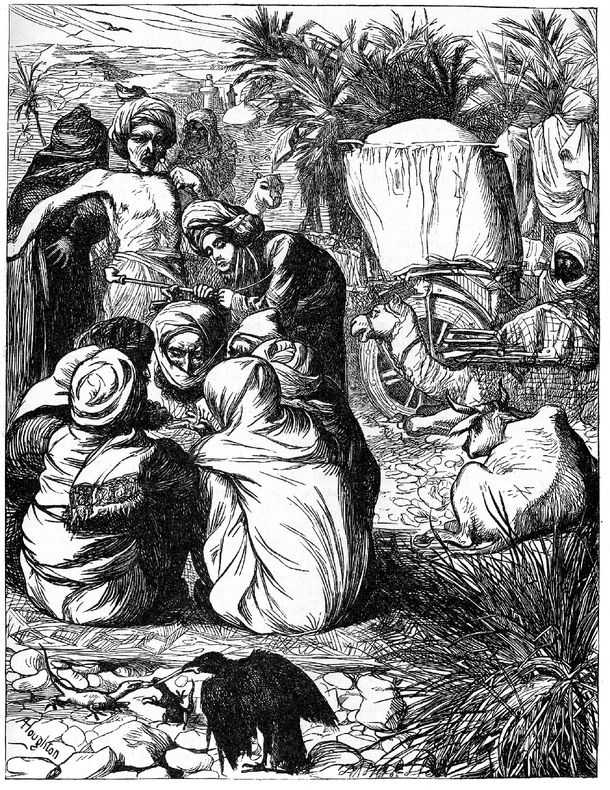

The young man and the governor of Damascus.

“ ‘When I came to this city, I dismounted at the jeweller’s, who received me with joy, and insisted on accompanying me to my house, to show me that no one had been in it during my absence. The seal was still entire on the lock. I entered, and found everything as I had left it.

“ ‘In cleaning and sweeping the room in which I had feasted the two ladies, one of my servants found a golden necklace in the form of a chain, in which were set, at intervals, ten very large and perfect pearls. He brought it me, and I knew it to be the necklace which I had seen on the neck of the young lady who was poisoned. I supposed that the clasp had given way, and it had fallen without my perceiving it. I could not look at it without shedding tears; for it brought to my recollection the charming creature whom I had seen expire in such a cruel manner. I wrapped it up and put it carefully in my bosom.

“ ‘In a few days I had recovered from the fatigue of my journey. I began to visit the friends with whom I had been formerly acquainted. I gave myself up to all kinds of pleasure, and gradually spent all my money. Embarrassed for the want of funds, instead of selling my goods I resolved to dispose of the necklace; but my ignorance of the value of pearls brought me into trouble, as you will hear.

“ ‘I went to the bazaar, where I called aside one of the criers. Showing him the necklace, I told him I wished to sell it, and begged him to exhibit it to the principal jewellers. The crier was surprised at the splendour of the ornament. ‘Ah, what a beautiful thing!’ cried he, when he had admired it for some time. ‘Our merchants have never seen anything so rich and costly. They will be glad to buy it; and you need not doubt their setting a high price on it, and bidding against each other.’ He led me into a shop, which I found belonged to the owner of my house. ‘Wait for me here,’ said the crier; ‘I shall soon return and bring you an answer.’

“ ‘Whilst he went about with great secresy to the different merchants to show the necklace, I seated myself by the jeweller, who was very glad to see me; and we entered into conversation on various subjects. The crier returned; and taking me aside, instead of telling me, as I expected he would, that the necklace was valued at two thousand scherifs at the least, he assured me, that no one would give me more than fifty. ‘They say,’ added he, ‘that the pearls are false: determine whether you will let it go at that price.’ As I believed what he said, and was in want of money, I replied: ‘I will trust your word and the opinion of men who are better acquainted with these matters than I am; deliver up the necklace, and bring me the money directly.’

“ ‘The crier had, in fact, been sent to offer me fifty scherifs by one of the richest jewellers in the bazaar, who had only mentioned this price to sound me, and ascertain if I knew the worth of the article I wanted to sell. So soon as he received my answer, he took the crier with him to an officer of the police, to whom he showed the necklace, saying: ‘Sir, this is a necklace that has been stolen from me; and the thief, who is disguised as a merchant, has had the effrontery to offer it for sale, and is now actually in the bazaar. He is content to receive fifty scherifs for jewels that are worth two thousand: nothing can be a stronger proof that he has stolen the necklace.’

“ ‘The officer of the police sent immediately to arrest me; and when I appeared before him, he asked me if the necklace he had in his hand was the one which I had offered for sale in the bazaar. I acknowledged the fact. ‘And is it true,’ continued he, ‘that you would dispose of it for fifty scherifs?’ I confessed this also. ‘Then,’ said he, in a sneering tone, to his followers, ‘let him have the bastinado. He will soon tell us, in spite of his fine merchant’s dress, that he is nothing better than a thief; let him be beaten till he confesses.’ The anguish of the blows made me tell a lie: I confessed, contrary to truth, that I had stolen the necklace; and immediately the officer of police ordered that my hand should be cut off.

“ ‘This occasioned a great noise in the bazaar, and I had scarcely returned to my house when the owner of it came to me. ‘My son,’ said he, ‘you seem to be a prudent and well educated young man; how is it possible that you have committed so base an action as a theft? You told me the amount of your property, and I doubt not that you spoke the truth. Why did not you ask me for money? I would willingly have lent you some. But after what has passed I cannot allow you to remain any longer in my house. Determine what you will do; for you must seek another home.’ I was extremely mortified at these words, and entreated the jeweller, with tears in my eyes, to suffer me to stay in his house three days longer; and he granted my request.

“ ‘Alas!’ cried I, ‘what a misfortune is this! What shame have I endured! How can I venture to return to Moussoul? All that I can say to my father will never persuade him that I am innocent.’ Three days after this calamity had befallen me, a number of the attendants of the police officer came into my house, to my great astonishment, accompanied by my landlord and the merchant who had falsely accused me of having stolen the necklace from him. I asked them what they wanted; but instead of replying they bound me with cords, and loaded me with execrations, telling me that the necklace belonged to the governor of Damascus, who had lost it about three years before; and that at the same time one of his daughters had disappeared. Judge of my consternation at this intelligence! But I quickly determined how to act. ‘I will tell the truth,’ thought I; ‘the governor shall decide whether he will pardon me or put me to death.’

“ ‘When I appeared before the governor, I observed that he looked on me with an eye of compassion; and I considered this to be a favourable omen. He ordered me to be unbound. Then, addressing the merchant who was my accuser, and the landlord of my house, ‘Is this,’ he said, ‘the young man who offered the pearl necklace for sale?’ They immediately answered, ‘Yes.’ ‘Then,’ the governor continued, ‘I am convinced that he did not steal the necklace; and I am astonished at the unjust sentence that has been executed upon him.’ Encouraged by this speech, I cried, ‘My lord, I swear to you that I am innocent. I am certain, also, that the necklace never belonged to my accuser, whom I never saw before, and to whose horrible duplicity I owe the calamity that has befallen me. It is true that I confessed the theft; but I made the avowal against my conscience, compelled by the torments I was made to suffer, and for a reason which I am ready to relate, if you will have the goodness to listen to me.’ ‘I know enough already,’ replied the governor, ‘to be able to render you part of the justice which is your due. Let the false accuser be taken hence,’ continued he, ‘and let him undergo the same punishment which he caused to be inflicted on this young man, of whose innocence I am convinced.’

“ ‘The sentence of the governor was instantly executed. The merchant was led out and punished as he deserved. Then the governor desired all who were present to withdraw, and thus addressed me: ‘My son, relate to me, without fear, in what manner this necklace fell into your hands, and disguise nothing from me.’ I disclosed to him all that had happened; and owned that I preferred passing for a thief to revealing this tragical adventure. ‘O Allah!’ exclaimed the governor, as soon as I had done speaking, ‘thy judgments are incomprehensible, and we must submit without murmuring: I receive with entire submission the blow which thou hast been pleased to strike.’ Then he addressed himself to me in these words: ‘My son, I have heard the account of your misfortune, for which I am extremely sorry. I will now relate mine. Know that I am the father of the two ladies you have entertained.

“ ‘The first lady, who had the effrontery to seek you even in your own house, was the eldest of all my daughters. I married her at Cairo to her cousin, the son of my brother. Her husband died, and she returned here, corrupted by a thousand vices which she had learnt in Egypt. Before her arrival, the youngest, who died in so deplorable a manner in your arms, had been very obedient, and had never given me any reason to complain of her conduct. Her eldest sister formed a very close friendship with her, and by insensible degrees led her away into the path of wickedness.

“ ‘The day following that on which the youngest died, I missed her when I sat down to table, and inquired for her of her sister, who had returned home; but instead of making any reply, my eldest daughter began to weep so bitterly, that I foreboded some misfortune. I pressed her to answer my question.

“ ‘My father,’ replied she, sobbing, ‘I can tell you nothing more than that my sister yesterday put on her best dress, and her beautiful pearl necklace, and went out, and she has never returned.’ I caused search to be made for my daughter through the city, but could learn no tidings of her fate. In the meantime my eldest daughter, who, no doubt, began to repent of her fit of jealousy, continued to weep and to bewail the death of her sister: she even deprived herself of all kinds of food, and at length starved herself to death.

“ ‘Such, alas!’ continued the governor, ‘is the condition of man. Such are the evils to which he is exposed. But, my son, as we are both equally unfortunate, let us unite our sorrows, and never abandon each other. I will bestow my third daughter on you in marriage: she is younger than her sisters, and her conduct has been irreproachable. She is even more beautiful than her sisters were. My house shall be your home, and after my death you and she will be my only heirs.’ ‘My lord,’ said I, ‘I am overwhelmed by your kindness, and shall never be able to testify my gratitude. ’ ‘It is enough,’ interrupted he; ‘let us not waste time in useless words.’ Hereupon he caused witnesses to be summoned, and I married his daughter without further delay.

“ ‘The merchant, who had falsely accused me, was further punished by having all his property, which was very considerable, confiscated to my use. As you come from the governor, you may have observed in what high estimation he holds me. I must also tell you that a man, who was sent expressly by my uncles to seek me in Egypt, discovered, on passing through this city, that I resided here, and yesterday brought me letters from them. They inform me of the death of my father, and invite me to go to Moussoul to take possession of my inheritance; but as my alliance and friendship with the governor attach me to him, and I cannot think of quitting him, I have sent back the messenger with authority to my uncles legally to transfer all that belongs to me. And now I trust you will pardon me the incivility I have been guilty of, during my illness, in presenting you my left hand instead of my right.’

“ ‘This,” said the Jewish physician to the Sultan of Casgar, ‘is the story which the young man of Moussoul related to me. I remained at Damascus as long as the governor lived; after his death, as I was still in the prime of my life, I felt an inclination to travel. I traversed all Persia, and went into India; at last I came to establish myself in your capital, where I exercise, with some credit to myself, the profession of a physician.”

“The Sultan of Casgar thought this story entertaining. ‘I confess,’ said he to the Jew, ‘that thou hast related wonderful things; but to speak frankly, the story of the hunchback is still more extraordinary and much more entertaining, so do not flatter thyself with the hope of being reprieved any more than the others; I shall have you all four hanged.’ ‘Vouchsafe me a hearing,’ cried the tailor, advancing, and prostrating himself at the feet of the sultan; ‘since your majesty likes pleasant stories, I have one to tell which will not, I think, displease you.’ ‘I will listen to thee also,’ replied the sultan; ‘but do not entertain any hopes that I shall suffer thee to live if thy story be not more diverting than that of the hunchback.’ Then the tailor, with the air of a man who knew what he did, boldly began his tale in the following words:—