THE HISTORY OF NOUREDDIN AND THE BEAUTIFUL PERSIAN.

THE city of Balsora was for a long time the capital of a kingdom tributary to the caliphs. During the life of the Caliph Haroun Alraschid it was governed by a king named Zinebi. The great caliph and the king were the offspring of two brothers, and were, therefore, closely related. Zinebi, who was unwilling to trust the administration of his government to one vizier only, chose two to preside in his council. They were named Khacan and Saouy.

“The character of the vizier Khacan was distinguished by mildness, liberality, and kindness. His greatest pleasure consisted in obliging all who came in contact with him. He granted every favour that he could accord consistently with that justice he held himself bound to administer. The whole court of Balsora, the city, and every part of the kingdom held him in the highest esteem, and the whole region echoed with his well-earned praise.

“Saouy, on the other hand, was a very different man. His mind was a constant prey to fretfulness and chagrin. Without distinction of rank or quality, he repulsed every applicant who approached him. His avarice was so great that, instead of doing good and earning blessings by the use of the immense wealth he possessed, he even denied himself the common necessaries of life. No one could love such a man; nor was a word ever uttered in his praise. And what increased the general aversion in which the people held him was his great hatred of Khacan, whose benevolent and generous actions he always endeavoured to represent in a bad point of view, that they might tell to the disadvantage of that excellent minister. He was also continually on the watch to undermine Khacan’s credit with the king.

“One day, after holding a council, the king indulged in familiar conversation with these two ministers, and some other members of the court. The subject happened to turn upon those female slaves whom it is the custom to purchase, and who are considered by their possessors nearly in the light of lawful wives. Some of the nobles present were of opinion that beauty and elegance of form in a slave were a full equivalent for the qualifications possessed by those ladies of high birth, with whom, either for the sake of a splendid connection, or from motives of interest, alliances of marriage were frequently formed.

“Others, among whom was the vizier Khacan, maintained that mere beauty and charms of person by no means comprehended all that was requisite in a wife; that these qualities should be accompanied by wit, intelligence, modesty, and pleasing manners; and heightened, if possible, by a variety of acquirements and accomplishments. To persons who have important concerns to transact, and who have passed a tedious day in close application to their affairs, nothing, they contended, can be so grateful, when they retire from bustle and fatigue, as the company of a well instructed wife, whose conversation will equally improve and delight. On the other hand, they contended, a slave whose sole recommendation is her beauty, could never compare in attractions with such a companion.

“The king was of the latter party, and proved himself so by ordering Khacan to purchase for him a slave, who, perfect in all exterior charms of beauty, should, above everything, possess a well cultivated mind.

“Saouy, who had been of a contrary opinion to Khacan, was jealous of the honour shown to his colleague by the king, and said to Zinebi: ‘O my lord, it will be extremely difficult to find so accomplished a slave as your majesty requires; and if such a woman be found, which I can scarcely believe possible, she will be cheaply bought at the expense of ten thousand pieces of gold.’ ‘Saouy,’ replied the king, ‘you seem to think this too large a sum. It would be so, perhaps, for you; but is not excessive for me.’ At the same time he ordered his grand treasurer, who was present, to pay ten thousand pieces of gold to Khacan.

“As soon as Khacan returned home, he sent to summon a number of men, who traded in slaves, and charged them, when they should find such a female slave as he described, to give him immediate notice of it. Equally anxious to oblige the vizier Khacan, and to promote their own interest, the slave merchants promised to use every means in their power to procure such a slave as he wished to purchase; and, indeed, a day seldom passed, in which they did not bring some woman to him, but he found some fault with each one.

“Early one morning, while Khacan was on his way to the royal palace, a merchant presented himself with great eagerness, and seizing the vizier’s stirrup, informed him that a Persian merchant, who had arrived very late on the preceding evening, had a slave to sell, whose beauty far surpassed anything he had ever beheld; and, with respect to intelligence and knowledge, the merchant assured him, that she surpassed everything the world had ever known.

“Delighted with the news, which would, he hoped, afford him a good opportunity of making his court, Khacan desired that the slave might be brought to him on his return from the palace, and thereupon he continued his way.

“The merchant did not fail to wait upon the vizier at the hour appointed; and Khacan found that the slave possessed charms so far above his expectation, that he immediately gave her the name of the Beautiful Persian. Being a man of great knowledge and penetration, he soon discovered, by the conversation he held with her, that he might seek in vain for any slave, who could excel her in all the qualities required by the king. He enquired, therefore, of the merchant, what was the sum demanded for her by the Persian trader who had brought her.

“ ‘O my lord,’ replied the merchant, ‘the trader, who is a man of few words, protests that he cannot consent to make the smallest abatement of ten thousand pieces of gold. He has assured me in the most solemn manner, that without taking into account his own care, pains, and time, he has expended very nearly that sum in engaging various masters for the improvement of her mental accomplishments; and then there is the unavoidable expense of dress and maintenance. From the very moment when he purchased her, in her early infancy, he considered her worthy of royal regard. He spared nothing in her education, that might enable her to attain so high an honour. She plays on every instrument, sings and dances to admiration, writes better than the most skilful masters, and makes exquisite verses. There are no books she has not read; nor am I exceeding the truth when I assert, that there never existed, till now, so accomplished a slave.’

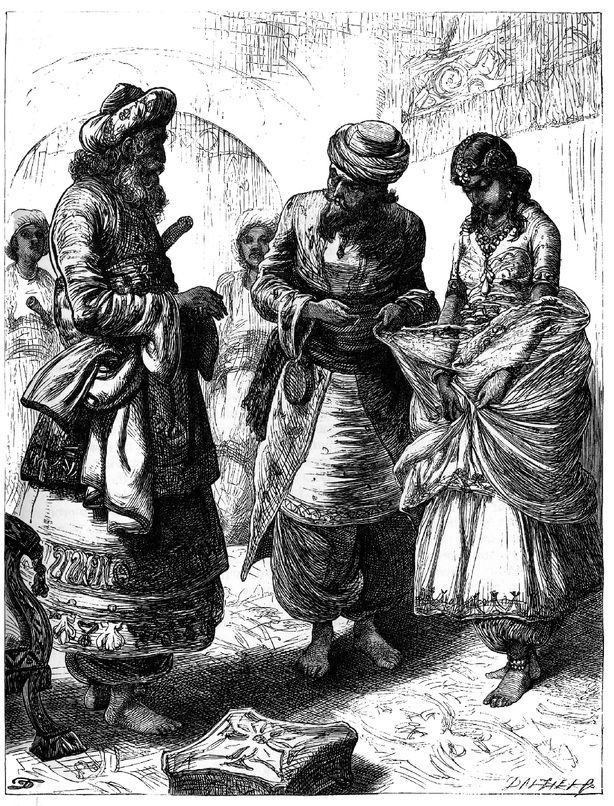

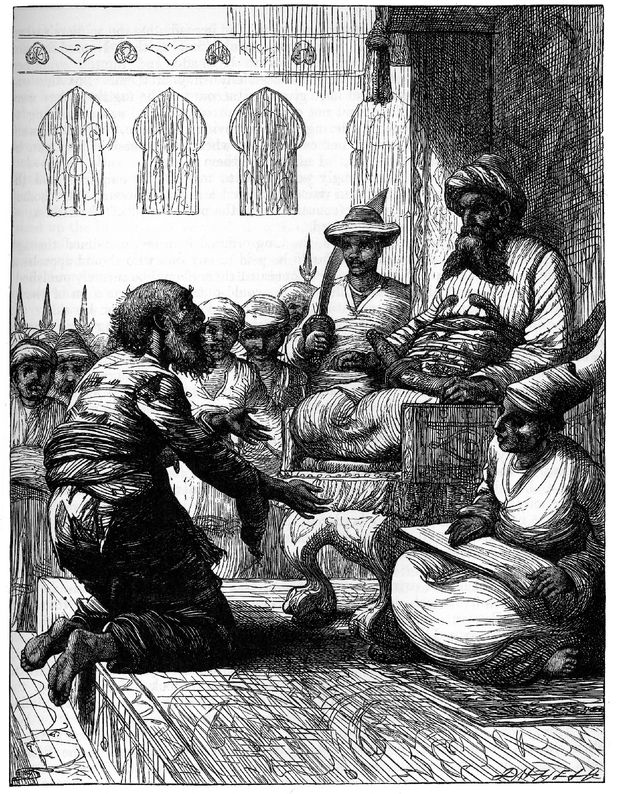

Purchase of the beautiful Persian.

“The vizier Khacan, who understood the merits of the Beautiful Persian much better than the merchant, who merely repeated what the trader had told him, was unwilling to defer the purchase to a future day. Accordingly he sent one of his people to the place where the merchant informed him the trader might be found, to desire the immediate attendance of the Persian.

“As soon as he arrived, Khacan said: ‘It is not for myself that I am desirous to purchase your slave, but for the king. You must, however, propose a more moderate price than the sum which the merchant has mentioned to me.’

“ ‘O vizier,’ replied the Persian, ‘it would be to me an infinite honour were I allowed to present my slave to his majesty; but I am aware that such a proceeding would not become a stranger like myself. All that I desire is to be reimbursed for the money which I have actually expended in her education. I may, I think, assert with confidence that his majesty will be perfectly content with his purchase.’

“The vizier Khacan was not inclined to dispute the matter. He ordered the required sum to be paid to the merchant, who, before he withdrew, addressed Khacan as follows:—‘O vizier, since the slave you have purchased is intended for the king, allow me the honour to inform you, that she is exceedingly fatigued with the long journey she has so lately made; and, though her present beauty may well seem incomparable, yet she will appear to far greater advantage if you keep her in your own house about a fortnight, allowing her, in the meantime, such attentions as she may require. When you present her to the king at the end of that time, she will ensure you honour and reward, and entitle me, I hope, to your thanks. You may perceive that the sun has rather injured her complexion; but when she has used the bath a few times, and has been adorned in the manner your taste will direct, you may be sure, my lord, she will be so changed, that you will find her beauty infinitely beyond what you can at present imagine.’

“Khacan thought the advice of the merchant very good, and determined to follow it. He allotted to the Beautiful Persian an apartment near that of his wife, whom he requested to allow the slave a place at her own table, and to treat her with all the respect due to a lady belonging to the king. He farther desired that his wife would cause the most magnificent dresses to be made, and to choose apparel peculiarly becoming to the beautiful stranger, whom he thus addressed: ‘The good fortune I have just procured to you could not possibly be greater. I have purchased you for the king, whose joy in possessing you will, I trust, be even greater than the satisfaction I feel in having acquitted myself of the commission with which I have been charged. But it is right that I should inform you that I have a son, who, though he does not want intelligence, has all the inconsiderate rashness of youth. As you cannot avoid sometimes meeting him, I mention this to put you on your guard.’ The Beautiful Persian thanked the vizier for his information and advice, and assured him she would profit by it. Thereupon the vizier withdrew.

“Noureddin, the son of whom the vizier had spoken, was accustomed, without restraint, to enter the apartment of his mother, with whom he usually took his meals. He was very handsome to look upon—young, agreeable, and intrepid. He had, moreover, a great deal of wit; and, accustomed to express himself with extraordinary facility, he had the enviable gift of being able to carry by persuasion every point he wished to gain. From the moment when Noureddin first saw the Beautiful Persian, although he knew from the solemn assurance of his father that she had been purchased for the king, he put no constraint upon himself, nor did he strive against the feeling of love that began to possess him, but permitted himself to be allured by the charms of the fair stranger, with which he had been struck from the first. His passion increased with the delight he experienced in conversing with her, and he determined to employ every means in his power to procure her for himself.

“The Beautiful Persian was also much struck by the graces of Noureddin. ‘The vizier does me great honour,’ said she to herself, ‘in purchasing me for the king of Balsora. I should, however, have esteemed myself very happy, if he had designed me for his own son.’

“Noureddin never failed to profit by the opportunities he had of beholding the Beautiful Persian; and his delight was to converse, to laugh, to jest with her. Never did he quit her till he was driven away by his mother, who would often say: ‘It is not, my son, becoming in a young man, like you, to waste so much time in a woman’s apartment. Go, and labour to render yourself worthy of one day succeeding to the office and dignity of your father.’

“In consequence of the long journey which the Beautiful Persian had lately taken, much time had elapsed since she had enjoyed the luxury of the bath. Accordingly, about five or six days after she had been purchased, the wife of the vizier gave orders to have the bath in their house prepared for her use. She sent thither the Beautiful Persian, accompanied with a train of female slaves, who were commanded to render her every possible service and attention. The fair slave quitted the bath, arrayed in a most magnificent dress, which had been provided for her. The vizier’s lady had given herself the more trouble on this occasion, from a desire to please her husband; for she wished to show him how much she interested herself in whatever concerned his happiness.

“A thousand times handsomer than when Khacan purchased her, the Beautiful Persian appeared before the wife of the vizier, who scarcely knew her again.

“Having gracefully kissed the hand of Khacan’s wife, the fair slave thus addressed her: ‘I know not, O lady, how I may appear to you in the dress you have had the goodness to order for me. Your women assure me it so well becomes me, they hardly know me again—but I fear they are flatterers. It is to yourself that I wish to appeal. If, however, they should speak the truth, it is to you, O my mistress, that I am indebted for all the advantage this apparel gives me.’

“ ‘O my daughter,’ replied the vizier’s lady, with a look of great delight, ‘what my women have told you is no flattery. I am better able to judge than they; and without taking into account your dress, which, however, becomes you wonderfully, be assured you bring with you from the bath a beauty so infinitely above what you possessed before, that I cannot sufficiently marvel at it. If I imagined the bath were still sufficiently warm, I would use it myself.’ ‘O, my mistress,’ replied the Beautiful Persian, ‘I have no words to express my sense of the kindness you have shown me, who have done nothing to merit your favour. With respect to the bath, it is admirable; but if you intend to use it, there is no time to be lost, as I have no doubt your women will inform you.’

“The wife of the vizier reflecting that many days had elapsed since she bathed, was desirous of profiting by the opportunity. She made known her intention to her women, and they soon prepared all the requisites for the occasion. But before the vizier’s lady went to the bath she commanded two little female slaves to remain with the Beautiful Persian, who had retired to her apartment, giving them a strict order not to admit Noureddin if he made his appearance during her absence.

“While the lady was in the bath Noureddin came; and, not finding his mother in her apartment, he went towards that of the Beautiful Persian. In the ante chamber, he found the two slaves. He enquired of them for his mother, and they informed him she was in the bath. Then he asked, ‘Where is the Beautiful Persian?’ They replied, ‘She is just returned from thence, and is now in her chamber. But we cannot allow you to enter, having been strictly forbidden to do so by our lady, your mother.’

“The chamber of the Beautiful Persian was only shut off by a tapestry curtain. Noureddin was determined to enter. The two slaves tried to prevent him from doing so, but he took each of them by the arm and turned them out of the ante chamber. They ran to the bath, making loud and bitter complaints; and in tears informed their lady that Noureddin had driven them from their post, and in contempt of their remonstrance had entered the chamber of the Beautiful Persian.

“The excessive boldness of her son angered the good lady extremely. She instantly quitted the bath, and dressed herself with all possible haste. But before she could get to the chamber of the Beautiful Persian, Noureddin had left it, and had gone away.

“The Beautiful Persian was extremely astonished, when she saw the wife of the vizier enter, bathed in tears, and looking like a distracted person. ‘O, my mistress,’ said she, ‘may I presume to ask what it is that thus grieves you? Has any accident befallen you at the bath, that you have been compelled to quit it so soon?’

“ ‘How!’ cried the vizier’s lady, ‘can you ask with so tranquil an air why I am thus disordered, when my son, Noureddin, has been in your chamber alone with you? Could a greater misfortune possibly happen either to him or to me?’

“ ‘I beseech you, O lady,’ returned the Beautiful Persian, ‘to inform me what evil can happen to yourself, or your son, in consequence of his having been in my chamber?’

“ ‘Has not my husband informed you,’ cried the vizier’s lady, ‘that you were purchased for the king; and has he not already cautioned you not to allow Noureddin to approach you?’

“To this speech the Beautiful Persian replied, ‘I have not forgotten his injunction, madam; ‘but Noureddin came to inform me that the vizier, his father, had altered his plans concerning me; and that, instead of reserving me for the king as he had purposed, I was destined to be the wife of Noureddin. I believed what he told me, and felt no regret at the change in my destiny; for I have conceived a great affection for your son, notwithstanding the few opportunities we have had of seeing each other. I resign, without regret, the hope of belonging to the king, and shall esteem myself perfectly happy if I am allowed to pass my whole life with Noureddin.’

“ ‘Would to Heaven,’ cried the vizier’s lady, ‘that what you tell me were true. It would give me very great delight. But believe me, Noureddin is an impostor; he has deceived you. It is impossible that his father should have made the change he talks of. O unhappy young man! and unhappy parents! and thrice unhappy father, who must suffer the dreadful consequences of the king’s wrath! Neither my tears nor my prayers will be able to soften Khacan, or to obtain pardon for his son, whom he will sacrifice to his just resentment, when he shall be informed of the boldness of which Noureddin has been guilty.’ Having spoken these words, she wept bitterly, and her slaves, who were all anxious for the safety of Noureddin, mingled their tears with hers.

“The vizier Khacan, who came home soon after, was greatly astonished to find his wife and slaves bathed in tears, and the Beautiful Persian extremely melancholy. He inquired the cause of their grief; upon which, instead of replying, they redoubled their moans and tears. This conduct so increased his surprise, that addressing himself to his wife, he said, ‘I insist upon being informed of the cause of this sorrow.’

“The unhappy lady was thus obliged to speak. But first she said to her husband, ‘Promise me that you will not impute blame to me in what I am going to tell you. I assure you the calamity has not happened from any fault of mine.’ Then without waiting for his reply, she continued; “While I was in the bath, attended by my women, your son came home, and availed himself of this fatal opportunity to persuade the Beautiful Persian that you had relinquished your intention of giving her to the king, and that you intended her for his wife. I leave you to imagine what I felt at hearing he had told so terrible a falsehood. This is the cause of my grief, on your account, and on account of our son also, for whom I have not the courage to entreat your clemency.’

“It is impossible to describe the mortification of the vizier Khacan, when he was informed of the insolence of Noureddin. ‘Ah!’ cried he, beating his breast, wringing his hands, and tearing his beard, ‘is it thus, wretched youth—unworthy to live—is it thus that you precipitate your father into a pit of destruction from the highest degree of happiness? You have ruined him, and with him destroy yourself. In his anger at this offence, committed against his very person, the king will not be satisfied with your blood or mine.’

“His wife endeavoured to comfort him, and said, ‘Do not thus despair, I can easily, by disposing of a part of my jewels, procure ten thousand pieces of gold, with which you may purchase a slave more beautiful than this, and one more worthy of the king.’ ‘What! do you believe,’ returned the vizier, ‘that the loss of ten thousand pieces of gold thus troubles me? It is not this that afflicts me; what I lament is the loss of honour which to me is the most precious of all earthly things.’ ‘Nevertheless,’ observed the lady, ‘it appears to me, my lord, that a loss that can be repaired by money is not of such very great importance.’

“But the vizier resumed: ‘Surely, you are not ignorant that Saouy is my most inveterate enemy. Can you not see, that as soon as he shall become acquainted with the affair, he will go immediately to the king to triumph at my expense? “Your majesty,” he will say, “is accustomed to speak of the affection and zeal which Khacan shows for your service. He has, however, lately proved how little he is worthy of your generous confidence. He has received ten thousand pieces of gold to purchase you a slave. He has duly acquitted himself of his honourable commission, and the slave he has bought is the handsomest ever beheld; but, instead of bringing her to your majesty, he has thought proper to make a present of her to his son. He has said, as it were, my son, take this slave; you are more worthy of her than the king.” Then will my enemy add, with his usual malice, “His son is now the possessor of this slave, and every day rejoices in her charms. That the affair is precisely as I have had the honour to state your majesty may be assured by examining into it yourself.” Do you not perceive, ’ added the vizier, ‘that should it occur to Saouy to calumnate me thus, I am every moment liable to have the guards of the king entering my house, and carrying off the beautiful slave. It is easy to imagine all the terrible evils which will ensue.’

The vizier’s vexation.

“To this discourse of the vizier, her husband, the lady answered: ‘Sir, the malice of Saouy is certainly great, and should this affair come to his knowledge, he will be certain to represent it unfavourably to the king. But how can he, or any person, be informed of what happens in the interior of this house? And even if it should be suspected, and the king should interrogate you on the subject, you may easily say that on a nearer acquaintance with the slave you did not find her so worthy of his majesty’s regard as she at first appeared; that the merchant had deceived you; that she indeed possessed incomparable beauty; but was beyond measure deficient in those qualities of the mind which she had been supposed to possess. The king will rely on your word, and Saouy will once more have the mortification of failing in his plans to ruin you, which he has already so often attempted in vain. Take courage, then; and if you allow me to advise, send for the brokers, inform the slave merchants that you are by no means satisfied with the Beautiful Persian, and direct them to look out for another slave.’

“This counsel appeared to the vizier Khacan very judicious. His mind accordingly became more tranquil, and he determined to follow his wife’s advice. He did not, however, in the least abate his anger towards his son.

“Noureddin did not appear for the rest of the day. Fearing to take refuge with any of those young friends whose houses he was in the habit of frequenting, lest his father would have him searched for there, he went to some distance from the city, and concealed himself in a garden, where he had never before been, and was wholly unknown. He did not return home till very late at night, and long after the time when he well knew his father was accustomed to go to rest. He prevailed upon his mother’s women to let him in, and they admitted him with great caution and silence. He went out the next morning before his father had risen, and was obliged to take the same precautions for a whole month, to his great chagrin and mortification. The women, however, did not in the least flatter him. They told him frankly, that the vizier, his father, was exceedingly angry with him, and had, moreover, determined to kill him at the first opportunity, whenever he should come in his way.

“The vizier’s lady knew from her women that Noureddin returned home every night; but she had not the courage to solicit her husband to pardon him. At length she summoned resolution to mention the subject. ‘O my husband,’ said she, ‘I have not ventured hitherto to speak to you concerning your son. I entreat you now to allow me to ask what you intend to do with him. No son can behave worse towards a parent than Noureddin has behaved towards you. He has deprived you of great honour, and of the satisfaction of presenting to the king a slave so highly accomplished as the Beautiful Persian. All this I acknowledge. But, after all what do you purpose doing? Do you wish to destroy him utterly? Are you aware that by doing so you may bring upon yourself a very heavy calamity, in addition to the comparatively light misfortune which you have already sustained? Do you not fear that malicious or malignant persons, in their endeavours to discover the reason why your son is driven from you, may ascertain the real cause, which you are so anxious to conceal? Should this happen, you will have fallen into the very misfortune which you have strenuously endeavoured to avoid.’

“The vizier replied, ‘What you say is perfectly just and reasonable; but I cannot resolve to pardon Noureddin till I have chastised him in some degree as he deserves.’ ‘He will be sufficiently punished,’ urged his wife, if you put in execution the plan that has this moment occurred to me. Your son returns home every night, and departs in the morning, before you rise. Wait this evening for his arrival, and let him suppose that you intend to kill him. I will come to his assistance; and by appearing to grant his life to my prayers, you may oblige him to take the Beautiful Persian on any terms you wish. I know he loves her, and the beautiful slave does not dislike him.’

“Khacan was well pleased with this advice. Accordingly, before Noureddin, who arrived at his accustomed hour, was allowed to enter the house, the vizier placed himself behind the door, and so soon as it was opened rushed out upon his son, and threw him to the ground. Noureddin, looking up, beheld his father standing over him with a poniard in his hand, ready to stab him.

“The mother of Noureddin arrived at this moment, and seizing the vizier by the arm, exclaimed: ‘What are you doing, my lord?’ ‘Let me alone,’ replied he, ‘that I may kill this unworthy son.’ ‘Ah, my lord, exclaimed the mother, ‘you shall first kill me; never will I permit you to im brue your hands in your own blood.’ Noureddin took advantage of this moment’s respite. ‘My father,’ cried he, his eyes suffused with tears, ‘I entreat your pity and forbearance. Grant me the pardon I presume to ask, in the name of that Being from whom you will yourself hope forgiveness on the day when we shall all appear before him.’

“Khacan suffered the poniard to be wrested from him, and released Noureddin, who instantly threw himself at his father’s feet, which he passionately kissed, to express how sincerely he repented having given him offence. ‘Noureddin,’ said the vizier, ‘thank your mother, for it is out of respect to her that I pardon you. I will even give you the Beautiful Persian, on condition that you engage, on oath, not to consider her as a slave, but as your lawful wife, whom you will never, on any account, sell or repudiate. As she has infinitely more understanding and good sense than you, she may be able to moderate those fits of youthful indiscretion by which you seem likely to be ruined.’

“Noureddin, who had not dared to expect so much indulgence, thanked his father with the warmest expressions of gratitude, and readily took the oath required of him. The Beautiful Persian and he were perfectly satisfied with each other, and the vizier was very well pleased at their union.

“Under these circumstances Khacan did not think it prudent to wait till the king spoke to him of the commission he had received. He took every opportunity of himself introducing the subject, and of pointing out the difficulties he experienced in acquitting himself in this affair to his majesty’s satisfaction. He played his part with so much address, that in a short time the king thought no more of the matter. Saouy had indeed heard some rumours of what had happened; but Khacan continued so much in favour that he did not venture to speak of his suspicions.

“More than a year elapsed; and this delicate business had gone on much more prosperously than the vizier Khacan could have any reason to expect. But one day, when he had indulged himself with a bath, some very urgent affair obliged him to hasten to the palace, heated as he was. The cold air struck him so forcibly that it brought on a sudden and grievous fever, which confined him to his bed. His illness continuing to increase, he soon became sensible that his last moments were approaching. He therefore addressed Noureddin, who never quitted his side, in these terms: ‘My son, I know not whether I have made a good use of the great riches which the goodness of Allah has bestowed upon me. You see that my possessions are of no avail to protect me from the hand of death. But the one thing that I am anxious to impress upon your mind, at this awful moment, is the duty of remembering the promise you have made me with respect to the Beautiful Persian. In full confidence of your integrity I die happy.’

“These were the last words, which the vizier uttered. He expired immediately afterwards, to the inexpressible grief of his family, the city, and the court. The king lamented the loss of a wise, zealous, and faithful minister; the city wept for its friend and benefactor. Never was there seen at Balsora so magnificent a funeral. The viziers, emirs, and indeed all the nobles of the court, were eager to support the bier, which they bore, in succession, on their shoulders to the place of burial, while all the citizens, rich and poor, accompanied the procession with weeping and lamentations.

“Noureddin showed every token of profound grief for the loss he had sustained. For a long time he suffered no person to have access to him. At length, however, he one day gave permission that one of his intimate friends should be admitted. This friend endeavoured to comfort him, and finding him inclined to listen to advice, represented to Noureddin, that since every token of respect which duty and affection could claim had been paid to the memory of his father, it was time for him to re-appear in the world, to associate with his friends, and to assert that rank and character to which, by virtue of his birth and merits, he could lay claim. ‘We offend against the laws of nature and civilised life,’ said this judicious counseller, ‘if we do not render to our deceased parents every respect which tenderness dictates; and the world will very justly censure, as a proof of savage insensibility, any omission in these rites of tenderness and duty; but when we have acquitted ourselves in such a manner as to be above the possibility of reproach, it becomes us then to resume our former habits, and to live in the world like persons who have a character to sustain. Therefore dry your tears, and strive to recover that air of gaiety which was wont to diffuse such universal joy amongst all who had the pleasure of your acquaintance.’

“The advice of this friend was reasonable enough, and Noureddin would have been spared many misfortunes which afterwards befell him if he had followed it in moderation. But impetuous in all he did, he yielded even too implicitly to the persuasions of his friend, whom he immediately entertained with great good will; and when the friend was retiring, Noureddin begged that he would visit him again the next day, and bring with him three or four of their common friends. By degrees, he formed a society of ten persons, all nearly of his own age, with whom he spent his time in continual feasts and scenes of pleasure; and not a day passed on which he did not dismiss every one of them with some present.

“Sometimes, to make his house even more agreeable to his friends, Noureddin would request the Beautiful Persian to be present at their feast. Though she had the good nature to comply cheerfully with his commands, she greatly disapproved his excessive expenditure; on which subject she freely gave him her opinion: ‘I have no doubt,’ she said, ‘that the vizier, your father, has left you great riches; but be not angry if I, a slave, remind you that however great your wealth may be, you will assuredly come to the end of it, if you continue your present style of living. It is reasonable sometimes to regale, and entertain friends; but to run every day into the same unbounded expense is to pursue the sure road to want and wretchedness. It were far better, for your reputation and honour, that you followed the steps of your deceased father, and put yourself in the way of obtaining those offices, in which he gained so much glory.’

“Noureddin listened to the Beautiful Persian with a smile, and when she had finished, he replied, ‘My love, I beg you will cease this solemn discourse, and let us talk only of pleasure. My late father held me constantly in such great restraint that I am now very glad to enjoy the liberty for which I so often sighed in former days. There will be always time enough to adopt the regular plan you recommend; a man of my years ought to indulge in the delights of youth.’

“What contributed, perhaps, more than any thing else to the embarrassment of Noureddin’s affairs, was his extreme aversion to reckon with his steward. Whenever the steward and his book appeared, they were instantly dismissed. Noureddin would say, ‘Get you gone, I can trust your honesty. Only take care that my table be always handsomely furnished.’ Then would the steward reply, ‘O Noureddin, you are my master. Allow me, nevertheless, very humbly to remind you of the proverb, which says, “he who spends much, and reckons little, will be a beggar before he is a wise man.” It is not only the enormous expense of your table, but your profusion in other respects is utterly without bounds. Were your treasures as huge as mountains, they would not be sufficient to maintain your expenses. ’ ‘Begone, I tell you,’ repeated Noureddin, ‘I want none of your lectures; continue to provide for my table, and leave the rest to me.’

“In the meantime, the friends of Noureddin were very constant guests at his table, and lost no opportunity of profiting by his easy temper. They were ever praising and flattering him, and pretending to discover some extraordinary virtue, or grace, in his most trifling action. But, especially, they never neglected to extol to the skies every thing that belonged to him; and indeed, they found it very profitable to do so. One of them would say, ‘O my friend, I passed the other day by the estate which you have in such and such a place; nothing can be more magnificent, or better furnished than the house; and the garden belonging to it is an absolute paradise of delights.’ ‘I am quite delighted that you are pleased with it,’ answered Noureddin. ‘Ho, there! bring us pen, ink, and paper; the place is yours; I beg to hear no words on the subject; I give it you with all my heart.’ Others had only to commend one of his houses, baths, or the public inns erected for the accommodation of strangers—a property very valuable from the considerable revenue it brought in—and these were instantly given away. The Beautiful Persian represented to Noureddin the injury he did himself; but, instead of regarding her admonitions, he continued in the same course of extravagance till he had parted with every thing he possessed.

“In short, Noureddin, for the space of a year, attended to nothing but feasting and merriment; and thus he lavished away the vast property which his ancestors, and the good vizier, his father, had acquired, and managed with so much care and attention. The year had hardly gone by, when, while he was at table one day, he heard a rapping at the door of his hall. He had dismissed his slaves and shut himself up with his friends, that they might enjoy themselves free from interruption.

“One of his companions offered to rise and open the door, but Noureddin prevented him, and went to the door himself. He found the visitor was his steward; and withdrew a little way out of the hall, to hear what was wanted, leaving the door partly open.

“The friend, who had risen, had perceived the steward; and curious to hear what he might have to say to Noureddin he placed himself between the hangings and the door, and heard him thus address his master: ‘O my lord, I beg you will pardon me for interrupting you in the midst of your pleasures; but what I have to communicate appears to me to be of such great importance, that I could not, consistently with my duty, avoid intruding upon you. I have just been making up my accounts, and I find that what I have long foreseen, and of which I have often warned you, has now arrived; that not a single coin is left of all the sums I have received from you to defray your expenses. Whatever other funds you have paid over to me are also exhausted; and your farmers and various tenants have made it appear to me so very evident, that you have made over to others the estates they rented of you, that I can demand nothing from them. Here are my accounts, my lord, examine them; if you wish that I should continue to serve you, provide me with fresh funds; or permit me to retire.’ Noureddin was so astonished at this intelligence that he could not answer a word.

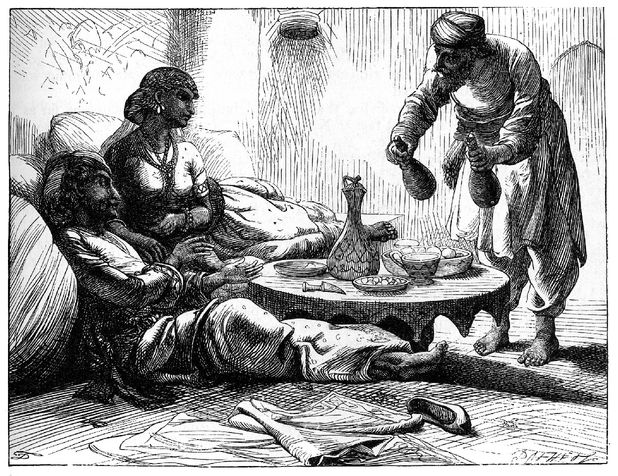

The beautiful Persian remonstrates with Noureddin against his extravagance.

“The friend, who had been listening, and who had heard all that passed, returned immediately to the rest of the party, and communicated the news. ‘You will do as you please,’ said he, ‘in the use you make of this information; with regard to myself, I declare to you, that this is the last time you will ever see me in Noureddin’s house.’ The others replied, ‘If things are really as you have represented, we have no more business here than yourself, and our foolish young friend will scarcely see us again.’

“Noureddin returned at this moment, and, though he endeavoured to put a good face upon the matter, and to diffuse the accustomed hilarity among his friends, he could not so dissemble but that they readily conjectured the truth of what they had just heard. Accordingly, he had hardly returned to his seat, when one of the company rose and thus addressed him: ‘O my friend, I am very sorry that I cannot enjoy the pleasure of your society any longer, therefore I hope you will excuse my departure.’ ‘What obliges you to leave us so soon?’ said Noureddin. ‘My lord,’ replied the guest, ‘my wife is brought to bed to-day, and you are well aware that in such cases, the presence of a husband is peculiarly necessary. ’ He then made a very low bow, and departed. Immediately afterwards another guest withdrew upon some pretence, and the whole party, one after another, followed the example, till there remained not one of all the friends who till this day had been the constant companions of Noureddin.

“Noureddin had not the least suspicion of the resolution his friends had taken not to see him again. He went to the apartment of the Beautiful Persian, to consult with her in private on the information he had received from his steward; and he openly expressed his sincere regret at having reduced his affairs to such great disorder.

“ ‘My lord,’ said the Beautiful Persian, ‘permit me to remind you, that, on this subject you never would listen to my counsel; you now see the result. I was not in the least deceived when I foretold the melancholy consequences you might expect, and great has been my concern that I could not make you at all conscious of the evil times that awaited you. Whenever I was anxious to speak to you on the subject you always replied: “Let us enjoy ourselves, and rejoice in the happy moments when fortune is favourable. The sky will probably not always be so bright.” Still I was not wrong when I reminded you, that we are ourselves able to build up our own fortune by the wisdom of our conduct. You would never listen to me; and I was compelled, in spite of my forebodings, to leave you to yourself.’

“ ‘I must acknowledge,’ replied Noureddin, ‘that I have been very wrong in neglecting the prudent advice you have given me, and in disregarding the dictates of your admirable wisdom; but, if I have expended all my estate, consider that it has been with a few select friends, whom I have long known; men of worth and honour, and who, full of kindness and gratitude, will not assuredly now abandon me.’ ‘My lord,’ said the Beautiful Persian, ‘if you have no other resource than the gratitude of your friends, believe me your hopes are ill-founded, as you will doubtless discover in a very short time.’

“ ‘O charming Persian,’ cried Noureddin, ‘I have a better opinion than you seem to have of my friends’ disposition to serve me. I will go round to all of them to-morrow morning, before their ordinary hour of coming hither, and you shall see me return with a large sum of money, which they will unite in subscribing for my wants. I have fully resolved that I will then change my manner of life, and use the money I obtain in some way of merchandise.’

“ On the next day Noureddin accordingly visited his ten friends, who all lived in the same street. He knocked at the door of the first, who happened to be one of the richest of them. A female slave appeared, and, before she opened the door, enquired who was there. ‘Tell your master,’ said Noureddin, ‘that it is Noureddin, son of the late vizier Khacan.’ The slave admitted him, and introduced him into a hall; then she went to the chamber, where her master was, to inform him that Noureddin was waiting to see him. ‘Noureddin!’ repeated the friend, in a tone of contempt, and so loudly that Noureddin heard him: ‘Go, tell him I am not at home—and whenever he comes again, give him the same answer.’ The slave returned, and informed Noureddin, that she had thought her master was at home, but that she had been mistaken.

“Noureddin went away confused and astonished. ‘Oh! the perfidious, pitiful wretch,’ cried he, ‘it was only yesterday that he protested to me I had no sincerer friend than himself, and now he treats me thus un-worthily! ’ He proceeded to the door of another who sent out the same reply. He then waited on a third, and went to all the rest in succession, receiving everywhere the same answer, though at the time they were everyone at home.

“These repulses naturally aroused the most serious reflections in the mind of Noureddin, and he clearly saw the fault he had committed in relying so fondly on these false friends, who had so assiduously surrounded his person. He now saw the vanity of protestations of regard, uttered amidst the enjoyment of splendid entertainments, and awakened only by an entertainer’s boundless liberality. ‘It is true,’ said he to himself, as tears flowed from his eyes, ‘it is only too true, that a man, situated as I have been, resembles a tree full of fruit; so long as any fruit remains on the tree it is surrounded by those who come to partake of its gifts, but when there is nothing more to be had, it is regarded no longer, but stands alone, stripped, and abandoned.’ So long as he was in the streets he endeavoured to put some restraint upon his feelings; but when he reentered his house, he went to the apartment of the Beautiful Persian, and gave full vent to his grief.

“So soon as the Beautiful Persian saw Noureddin return downcast and melancholy she understood that he had not derived from his friends the assistance he had expected. Therefore she said to him, ‘O my lord, are you now convinced of the truth of what I foretold?’ ‘Ah, my love,’ he replied, ‘what you foresaw is but too true. Not one of those men would receive me—see me—speak to me. Never could I have believed it possible that persons, who owe me so many obligations, and for whom I have deprived myself of all I possessed, could have treated me so cruelly. I am no longer master of my reason, and I much fear that, in the deplorable and wretched condition in which I now am, I may do something desperate, unless assisted by your kind and prudent counsels.’ ‘My lord,’ said the Beautiful Persian, ‘I know no other remedy for your misfortune than that of selling your slaves and furniture; you can thus raise a sum of money on which you may subsist till Heaven shall point out some other way of extricating you from your difficulties.’

“The remedy appeared to Noureddin extremely severe, but his present wants were very urgent. Therefore he first sold his slaves, who had become a useless burden, and for whose maintenance he could no longer provide. He lived for some time upon the money thus obtained, and, when this supply began to fail, he caused his furniture to be conveyed to the public mart, where it was sold greatly below its real value, as some of it was extremely rich, and had cost immense sums. Thus he was enabled to live for a considerable time. But at length this resource failed also; and now, as there remained nothing more to dispose of, he came again, and poured his griefs into the bosom of the Beautiful Persian.

“Noureddin did not in the least expect the proposal this prudent and generous woman now made him: ‘My lord,’ said she, ‘I am your slave, and you know the late vizier, your father, purchased me for ten thousand pieces of gold. I am well aware that I am not so valuable as I was at that time; but I flatter myself I may still produce a sum not much short of it. Therefore I counsel you to send me to the market and sell me immediately. With the money you thus obtain, which will be a very considerable sum, you may commence business as a merchant in some place where you are not known, and thus procure the means of living, if not in opulence, at least in a way that may render you happy and contented.’

“ ‘O charming, beautiful Persian!’ cried Noureddin, ‘is it possible that you can entertain such a thought? Have I given you so few proofs of my affection that you believe me capable of such meanness? And even if I could be so unworthy, should I not add the foulest perjury to my baseness, after the oath I made to my late father, which I would sooner die than break. No, never can I separate myself from one whom I love more than life itself; though your making to me so unaccountable a proposal proves only too clearly how far your affection to me falls short of that which I feel for you.’

“ ‘My lord,’ replied the Beautiful Persian, ‘I am convinced your love for me is as great as you describe it; and Heaven is my judge that my affection for you is not the less; and Heaven knows with what extreme repugnance I prevailed on myself to make the proposal which has so much displeased you; but, to meet the objection you offer, I have only to remind you that necessity has no law. Believe me, my love for you cannot possibly be exceeded by yours for me, nor can it ever change, or cease, to whatever master I may belong. Never can I know any joy so great as that of being re-united to you, if, as I hope may be the case, your affairs should ever be so prosperous as to enable you to re-purchase me. The necessity to which we are now driven is extremely severe; but, alas! what other means are left to extricate us from the poverty which now surrounds us!’

“Noureddin, who knew too well the truth of what the Beautiful Persian had been saying to him, and who had no other resource against the most ignominious poverty, was compelled to adopt the measure she proposed. Therefore, though with the most inexpressible regret, he conveyed her to the market-place, where female slaves were sold; and, addressing himself to a broker, said, ‘Hagi Hassan, I have a slave here whom I wish to sell; I beg of you to learn what price the purchasers will give for her.’

“Hagi Hassan desired Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian to enter a chamber, where the latter removed the veil that concealed her face; Hagi Hassan was struck with astonishment and said, ‘Can I be deceived? Is not this the slave whom the late vizier, your father, purchased for ten thousand pieces of gold?’ Noureddin assured him this was the Beautiful Persian herself; and Hagi Hassan, giving him reason to expect a large sum, promised to exert all his ability to obtain for her the best price possible.

“Hagi Hassan and Noureddin left the chamber where the Beautiful Persian remained. They went in search of the merchants who were occupied in purchasing various slaves, Greeks, Franks, Africans, Tartars, and others. Thus Hagi Hassan was obliged to wait till they had completed their business. When they were ready, and again assembled together, he said, with much pleasantry in his look and manner, ‘My good fellow-countrymen, every round thing is not a nut; every long thing is not a fig; every red thing is not flesh; and every egg is not fresh. I will readily agree that in the course of your lives you have seen and purchased many slaves; but never have you beheld a single one who can in the least compare with her I am about to show you. She is, in truth, a perfect slave. Come with me and look at her. I wish you yourselves to fix the price at which I ought to offer her.’

“The merchants followed Hagi Hassan, who opened the door of the apartment where the Beautiful Persian was. They beheld her with astonishment, and immediately agreed that to begin with, they could not possibly set a smaller price upon her than four thousand pieces of gold. They then left the room, and Hagi Hassan, after fastening the door, followed them out a little way, crying, with a loud voice, ‘The Persian slave for four thousand pieces of gold.’

“Not one of the merchants had yet spoken; and they were consulting together about the sum they should bid for her, when the vizier Saouy made his appearance. He had perceived Noureddin in the market, and said to himself, ‘It appears that Noureddin is still raising money from the sale of his effects’—for he knew that the young man had been selling some of his furniture—‘and is come hither to purchase a slave.’ As he was advancing, Hagi Hassan cried out a second time, ‘The Persian slave for four thousand pieces of gold.’

“Saouy imagined, from hearing this high price, that the slave must possess very extraordinary beauty. He immediately felt a strong desire to see her, and urged his horse forward towards Hagi Hassan, who was surrounded by the merchants. ‘Open the door,’ said he, ‘and let me see this slave.’ It was contrary to custom to permit a slave to be seen by any indifferent person after the merchants had seen her, and while they were bargaining for her; but they had not the courage to urge their right against the authority of the vizier, nor could Hagi Hassan avoid opening the door. He therefore made a sign to the Beautiful Persian to approach, so that Saouy might see her without alighting from his horse.

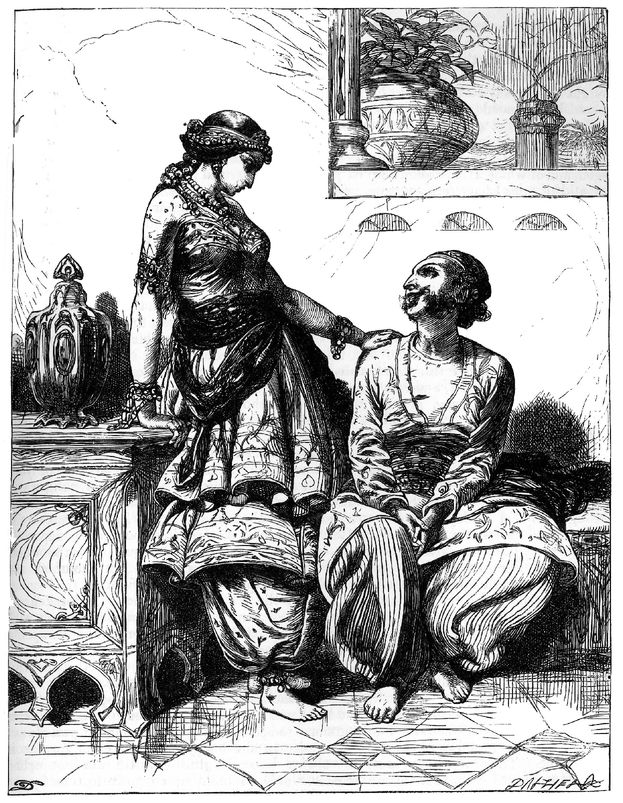

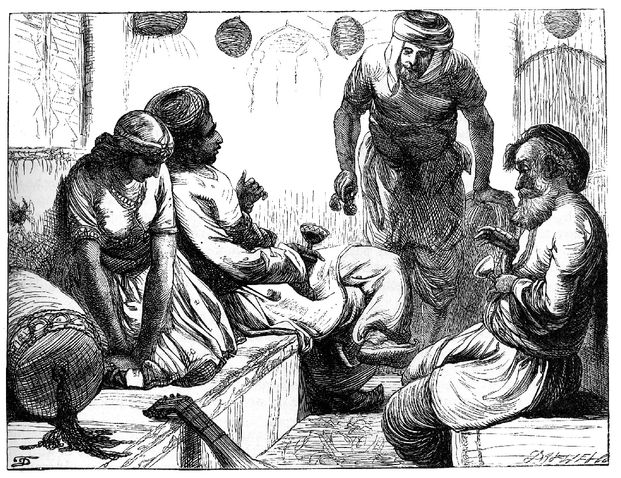

Sale of the beautiful Persian.

“When Saouy beheld the extraordinary beauty of this slave, he was beyond measure surprised; and knowing the name of the agent employed to sell her, who was a person with whom he had occasionally had business, he said, ‘Hagi Hassan, four thousand pieces of gold is, I think, the price at which you value her.’ ‘Yes, my lord,’ replied Hassan. ‘The merchants whom you see here, have just now agreed that I should put her up at that price. I now expect them to advance upon the price, and expect much more by the time they have done bidding.’ ‘I will give the money myself,’ said Saouy, ‘if no one offers more.’ He immediately gave the merchants a glance, which sufficiently expressed that he must not be outbidden. He was, indeed, so much feared by them all, that they took especial care not to open their lips, even to complain of the manner in which he had violated their rights.

“When the vizier had waited some time, and found that none of the merchants would bid against him: ‘Well, what do you wait for?’ he said to Hagi Hassan. ‘Go, find the seller, and conclude the bargain with him for four thousand pieces of gold, or learn what he intends farther.’ He did not at the time know that the slave belonged to Noureddin.

“Hagi Hassan locked the chamber door, and went to talk over the affair with Noureddin. ‘My lord,’ said he, ‘I am very sorry to be obliged to communicate very unpleasant intelligence: your slave is about to be sold for a miserable price.’ ‘How is this?’ enquired Noureddin. ‘My lord,’ said Hagi Hassan, ‘the business at first looked promising enough. The moment they had seen her, the merchants, without any doubt or hesitation, desired me to put her up at four thousand pieces of gold. Just as I had cried her at that price the vizier Saouy arrived. His presence immediately shut the mouths of all the merchants, who were evidently disposed to raise her to at least the price which she cost the late vizier, your father. Saouy will only give four thousand pieces of gold, and I assure you it is with great reluctance that I am come to report to you his inadequate offer. The slave is yours; and I cannot advise you to part with her at that price. You and all the world know the character of the vizier. Not only is the slave worth infinitely more than the sum he has offered, but he is so unprincipled a man that he will very likely invent some pretence for not paying you even the money he now offers.’

“ ‘Hagi Hassan,’ replied Noureddin, ‘I am much obliged to your for your advice. Do not imagine that I shall ever permit my slave to be sold to the enemy of my house. I am certainly in great need of money, but I would sooner die in the most abject poverty than part with her to Saouy. I have, therefore, one favour to request of you—that, as you are acquainted with all the customs and artifices of this kind of business, you will tell me what I must do to prevent Saouy from obtaining her?’

“Hagi Hassan replied, ‘That is easily done. Pretend, that having been in great wrath with your slave, you swore you would expose her in the public market, and that you have accordingly done so. But say that you had no intention of selling her, but merely wished to redeem your oath. This will satisfy every one, and Saouy will have nothing to say against it. Be ready, then; and in the moment when I shall present her to Saouy, come up and say that though her bad conduct made you threaten to sell her, you never intended to part with her in earnest.’ Thereupon he led forth the Beautiful Persian to Saouy, who was already before the door, ‘My lord,’ said he, leading her to him, ‘there is the slave, take her, she is yours.’

“Hagi Hassan had hardly finished these words, when Noureddin seized hold of the Beautiful Persian, and, drawing her towards him, gave her a box on the ear. ‘Come here, thou stubborn one,’ said he, in a tone sufficiently loud to be heard by every one, ‘and get thee gone. Your abominable temper compelled me to take an oath to expose you in the public market; but I shall not sell you at present. It will be time enough to do that when every other means fail.’

“The vizier was very angry at this action of Noureddin’s. ‘Worthless spendthrift,’ he exclaimed, ‘would you have me believe that you have anything left to dispose of except this slave?’ As he spoke he rode his horse at Noureddin, and endeavoured to seize the Beautiful Persian. Stung to the quick by the affront which the vizier had put upon him, Noureddin let the Beautiful Persian go, and desiring her to wait, threw himself immediately upon the horse’s bridle, and compelled him to fall back three or four paces. ‘You despicable old wretch,’ said he, to the vizier, ‘I would tear you to pieces this instant, if I were not restrained by regard for those about me.’

“As the vizier Saouy was not loved by any one, but, on the contrary, was hated by all, those present were delighted at the mortification he had received, and made known their satisfaction to Noureddin by various signs; giving him to understand that if he revenged himself in any way he chose he would experience no opposition from them.

“Saouy made every effort to oblige Noureddin to let go his horse’s bridle; but the latter being a young man of great strength, encouraged by the good wishes of those present, pulled the vizier from his horse into the middle of the street, and after giving him a great many blows, dashed his head forcibly against the pavement, till it was covered with blood. Half a score of slaves who were in waiting on the vizier would have drawn their sabres, and fallen upon Noureddin, but were prevented by the merchants. ‘What are you about to do?’ said these, ‘if one is a vizier, do you not know that the other is a vizier’s son? Let them decide their own quarrel; perhaps one day they may become friends, but in any case, should you kill Noureddin, your master, powerful as he is, will not be able to screen you from justice.’ Noureddin, fatigued with beating the vizier, left him in the middle of the street, and again taking charge of the Beautiful Persian, returned home, amidst the acclamations of all the people, who much commended him for what he had done.

“Exceedingly bruised by the blows he had received, Saouy, assisted by his servants, with the greatest difficulty got up, and was extremely mortified to find himself besmeared all over with blood and mire. Supporting himself upon the shoulders of two of his slaves, he went, in that forlorn condition, immediately to the palace; and it increased his confusion to see that, though all gazed at him with surprise, he was pitied by none. When he arrived near the apartment of the king, he began to weep and to cry out for justice, in a most pathetic manner. The king ordered him to be admitted; and as soon as he appeared, desired to know how it happened that he had been so ill-treated, and who had put him into so lamentable a state. ‘O great king,’ exclaimed Saouy, ‘it is because I am honoured with your majesty’s favour, and am allowed a share in your important counsels, that I have been treated in the shocking manner you now behold.’ ‘Let me have no useless words,’ said the king; ‘tell me at once what is the meaning of the affair, and who is the offender. If any one has done you a wrong, I shall know how to bring him to repentance.’

“ ‘O my king,’ said Saouy, who took care to give everything a turn in his own favour, ‘I was going to the market of female slaves, in order to purchase a cook, whom I required. On my arrival there, I heard them crying a slave for four thousand pieces of gold. I desired to see this slave, and I found her the most beautiful creature that eyes ever beheld. After looking upon her with the most extreme satisfaction, I asked to whom she belonged, and I was informed that Noureddin, the son of the late vizier Khacan, wished to sell her.’

“ ‘Your majesty may remember that about two or three years since you ordered to be paid to that minister ten thousand pieces of gold, with which he was charged to purchase a slave. He employed it in purchasing the one in question; but instead of bringing her to your majesty, whom it would appear he thought unworthy of her, he presented her to his son. Since his father’s death this son has, by the most unbounded extravagance of every sort, dissipated his whole fortune, so that nothing remained to him but this slave, whom he at length determined to sell, and who was in fact this day brought to market. I sent to speak with him; and without alluding in any way to the prevarication, or rather perfidy, of which his father had been guilty towards your majesty, I said to him, in the civillest manner possible, “Noureddin, the merchants, as I understand, have put up your slave at four thousand pieces of gold; and I doubt not that the competition which seems likely to take place, will raise the price very considerably; but trust to me, and sell her for the four thousand pieces of gold; I wish to purchase her for the king, our lord and master. This transaction will give me a good opportunity of recommending you to his majesty’s favour, which you will find of infinitely more value than any sum of money the merchants can give you.”

“ ‘Instead of answering me with the courtesy and civility I had a right to expect, Noureddin cast upon me a look of the most insolent contempt. “Thou detestable old wretch,” said he, “sooner than sell my slave to thee, I would give her to a Jew for nothing.” “But, Noureddin,” cried I, without allowing myself to be carried away by passion, however great the provocation I had received, “when you thus speak, you do not consider the insult you are offering to the king, to whose kindness your father, like myself, owed all that he enjoyed.”

“ ‘This remonstrance, which ought to have softened him, only irritated him the more. He rushed upon me like a madman, and without any regard for my age or dignity, pulled me off my horse, beat me till he was weary, and at last left me in the condition in which your majesty now sees me. I beseech you to consider that it is through my zeal for your interests that I have suffered this shocking insult.’ Having finished his speech, he hung down his head, and turning away, gave free course to his tears, which flowed in abundance.

“The king, imposed upon by this artful tale, and highly incensed against Noureddin, showed by his countenance how violent was his anger; and turning round to the captain of the guard who was near him, said, ‘Take forty of your men; go and sack Noureddin’s house, and after ordering it to be razed to the ground, return hither with him and his slave.’

“The captain of the guard did not quit the apartment so expeditiously, but that a groom of the chamber, who had heard the order given, got the start of him. The name of this officer was Sangiar. He had been formerly a slave belonging to the vizier Khacan, and had been introduced by him into the king’s household, where by degrees he had raised himself to the rank he held.

“Full of gratitude to his dead master, and of affection for Noureddin, whom he had known from the hour of his birth, and fully aware of the hate which Saouy had long entertained against the house of Khacan, Sangiar trembled with apprehension when he heard the order. He said to himself, ‘The conduct of Noureddin cannot be so bad as Saouy represents it. The malicious vizier has prejudiced the king, who will condemn Noureddin to death without giving him the least opportunity of justifying himself. ’ Sangiar therefore ran with such speed, that he arrived just in time to inform Noureddin of what had happened at the palace, and to give him an opportunity of escaping with the Beautiful Persian. He knocked at the door in so violent a manner that Noureddin, who for a long time had been without a servant, came and opened it himself, without a moment’s delay. ‘O my dear lord,’ said Sangiar to him, ‘there is no safety for you at Balsora; depart, and escape from the city without losing an instant.’

“ ‘How is this?’ replied Noureddin. ‘What has happened that I should depart so soon?’ ‘Go, I entreat you,’ resumed Sangiar, ‘and take your slave with you. Saouy has just related to the king, in such a manner as best suited his purpose, the encounter he had with you to-day, and the captain of the guard will be here in an instant with forty soldiers to sieze you and your slave. Take these forty pieces of gold to assist you in gaining some place of safety; I would give you more, but this is all I have about me. Excuse me if I depart at once—I leave you with great reluctance—but it is for the benefit of us both, as I am very anxious that the captain of the guard should not see me.’ Sangiar received the thanks of Noureddin, and immediately withdrew.

“Noureddin went to acquaint the Beautiful Persian of the necessity they were both under of making their escape that very instant. She only stayed to put on her veil; and then they quitted the house together, and had the good fortune not only to get out of the city without being discovered, but even to reach the mouth of the Euphrates, which was not far distant, and to embark on board a vessel then ready to weigh anchor.

“Indeed, at the very moment when they appeared, the captain was upon the deck in the midst of his passengers. ‘My friends,’ said he, ‘are you all here? Have any of you any business in the city, or have you forgotten any thing?’ To this the passengers replied they were all ready, and he might sail whenever he pleased. Directly Noureddin came on board, he enquired to what place the vessel was bound, and was delighted to find it was going to Baghdad. The captain then gave orders to weigh anchor and set sail; and favoured by the wind, the ship had soon left Balsora far behind.

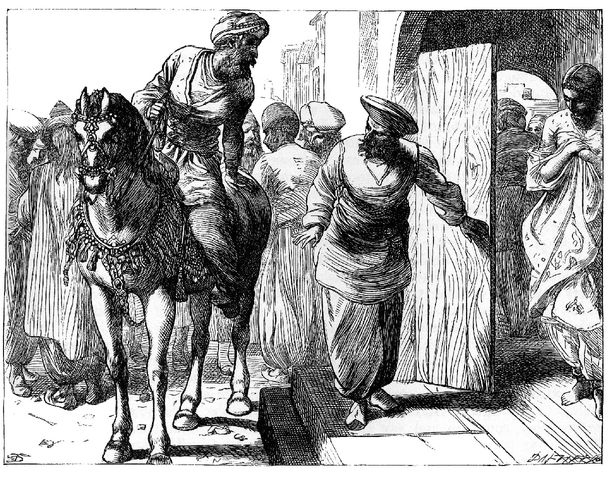

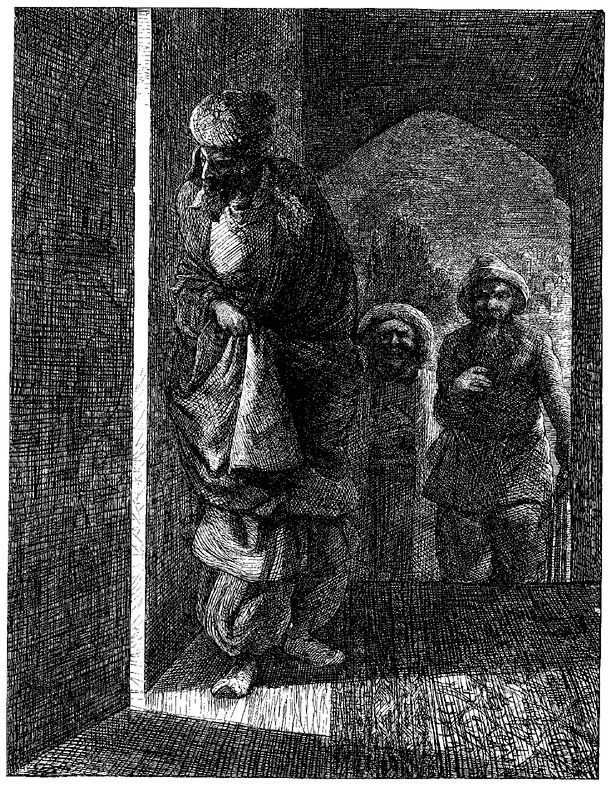

Saouy complains to the King.

“Let us now relate what happened at Balsora, while Noureddin, accompanied by the Beautiful Persian, was escaping from the anger of the king.

“The captain of the guard hastened to the house of Noureddin, and knocked at the door. As no one answered, he caused it to be broken open; and immediately the soldiers rushed in, and searched every part of the house, but could find neither Noureddin nor his slave. The captain then ordered enquiries to be made, and himself examined some of the neighbours, as to whether they had seen any thing of them. But this was fruitless, for even if these people could have given any account of the fugitives, they were so cordially attached to Noureddin, that not one of them would have said any thing to his injury. While the men were plundering and destroying the house, the captain went to inform the king of his failure. ‘Let every place, where it is possible they can be concealed, be searched,’ said the king; ‘I must have them found.’

“The captain of the guard accordingly went back to make fresh enquiries, and the king, unwilling any longer to detain the vizier, dismissed him with honour. ‘Go home,’ said he, ‘and give yourself no further concern about the punishment of Noureddin. I will take care that his insolence is chastised.’

“That no means might be left untried, the king ordered it to be proclaimed through the city, that a thousand pieces of gold should be paid to any one who should apprehend Noureddin and his slave; and that whoever concealed them should be severely punished; but, notwithstanding all his care and diligence, he could obtain no information of them; so that the vizier Saouy had no consolation but that of having the king on his side.

“In the meantime Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian were pursuing their journey with all the good fortune possible; and in due time they arrived at the city of Baghdad. As soon as the captain perceived the place, glad to be so near the completion of his voyage, he exclaimed, addressing himself to the passengers, ‘rejoice, my friends, there is the great and wonderful city, to which people from every part of the world are constantly flocking. You will there find inhabitants without number; and, instead of the chilling blasts of winter, or the oppressive heats of summer, you will perpetually feel the mildness and beauty of spring, and enjoy the delicious fruits of autumn.’

“When they had cast anchor a little below the city, the passengers quitted the ship and went to their respective habitations. Noureddin gave five pieces of gold for the passage, and landed with the Beautiful Persian. As he had never before been at Baghdad he was wholly ignorant where to seek shelter. They walked, for a considerable time, by the side of the gardens which bordered the Tigris, one of which was bounded by a long and handsome wall. When they came to the end of this, they turned into a long well-paved street, in which they perceived the garden gate, near a very delightful fountain.

“The gate, which was extremely magnificent, was locked. Before it was an open vestibule, with a sofa on each side. ‘Here is a most convenient place,’ said Noureddin to the Beautiful Persian. ‘Night is coming on; and as we refreshed ourselves with food before we left the ship, I recommend that we remain here. To-morrow morning we shall have ample time to look for a lodging. What say you?’ ‘You know, my lord,’ replied the Beautiful Persian, ‘that I have no wish but to please you; if you desire to remain here I shall be happy to stay. Then each of them took a draught from the fountain, and seating themselves on one of the sofas conversed for some time, till, lulled by the agreeable murmur of the waters, they fell into a profound sleep.

“This garden, which belonged to the caliph, had in the middle of it a grand pavilion, called the painted pavilion; because it was ornamented with pictures in the Persian style, painted by masters whom the caliph had sent for from Persia. The grand and superb saloon which this pavilion contained was lighted by eighty windows, with a large chandelier in each; but, by the express command of the caliph, these were never lighted up except when he was there; but when lighted they made a most beautiful illumination, which could be seen at some distance in the country, and over a great part of the city.

“This garden was inhabited only by the person who kept it in order; a very aged officer, named Scheich Ibrahim, to whom the caliph had given this post as a reward for former services. He had received very particular injunctions not to admit into it all persons indiscriminately; and particularly, to prevent the visitors from sitting or resting upon the sofas placed without the gate, which were to be constantly kept with the greatest care; and, therefore, all whom he found offending were to be punished.

“This officer, who had been called out on some business, had not yet returned; but coming home before the day closed he perceived two persons sleeping on one of the sofas, their heads covered with a linen turban to protect them from the gnats. ‘So, so!’ said Scheich Ibrahim to himself, ‘it is thus that you disobey the commands of the caliph? But I shall teach you to respect them.’ He then, without any noise, let himself out through the gate, and soon after returned with a large cane in his hand and his sleeve tucked up. Just as he was going to strike with all his force, he paused: ‘Scheich Ibrahim,’ said he to himself, ‘you are going to beat these people without considering that, perhaps, they are strangers, who know not where to lodge, and are ignorant of the caliph’s prohibition. It will be better, first, to know who they are.’ He then gently raised up the linen which covered their heads, and was much surprised when he saw a young man of an extremely good, pleasing countenance, and a young woman of extraordinary beauty. He then roused Noureddin, by pulling him softly by the feet.

“Noureddin immediately lifted up his head; and, as soon as he saw an old man with a long white beard at his feet, he rose up on the sofa in a kneeling position, and seizing the visitor by the hand, which he kissed, he said, ‘good father, may Heaven preserve you; what do you wish of me?’ ‘My son,’ said Scheich Ibrahim, ‘who are you? whence come you?’ ‘We are strangers, who have just arrived,’ returned Noureddin, ‘and we wish to stay here till to-morrow morning.’ ‘You will be very badly lodged here,’ replied Scheich Ibrahim; ‘you will do better to go in with me. I will furnish you with a much more suitable place to sleep in; and the view of the garden, which is very beautiful, will delight you during the short portion of day that remains.’ ‘And is this garden yours?’ said Noureddin. ‘Certainly it is,’ said Scheich Ibrahim, smiling, ‘it is an inheritance I received from my father. Come in, I entreat you; you will not repent seeing it.’

“Noureddin rose and expressed to Scheich Ibrahim how much he was obliged by his politeness. Thereupon he went with the Beautiful Persian into the garden. Scheich Ibrahim locked the gate; and, walking before his guests, conducted them to a place whence they might see at one view the arrangement, grandeur, and beauty of the whole.

“Noureddin had seen many very beautiful gardens at Balsora, but never one that could be compared to this. When he had well observed everything, and had been amusing himself for some time by walking along the paths, he turned round to the old man who accompanied him, and asked his name. As soon as he had learned it, he said: ‘Scheich Ibrahim, I must confess that your garden is wonderful: may Heaven spare you many years to enjoy it. We cannot sufficiently thank you for the favour you have done us in showing us a place so extremely worth seeing: it is only right that we should in some way express our gratitude. Take, therefore, I pray you, these two pieces of gold, and endeavour to procure us something to eat, that we may all make merry together.’

“At the sight of the two pieces of gold, Scheich Ibrahim, who had a great admiration for that metal, could not help laughing in his sleeve. He took the money; and, as he had no assistant, left Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian by themselves, while he went to execute the commission. ‘These are good people,’ said he to himself, gleefully. ‘I should have done myself no small injury if I had ill-treated or driven them away. With the tenth part of this money I can entertain them like princes, and the remainder I may keep for my trouble.’

“While Scheich Ibrahim was gone to purchase some supper, of which he remembered that he was himself to partake, Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian walked about the garden till they came to the painted pavilion, situated in the middle of it. They stopped for some time to examine its wonderful structure, size, and loftiness; after they had gone round it, surveying it on all sides, they ascended by a grand flight of steps, formed of white marble, to the door of the saloon, which they found locked.

“They had just descended the steps when Scheich Ibrahim returned, laden with provisions. ‘Scheich Ibrahim,’ said Noureddin, in great surprise, ‘did you not say that this garden belonged to you?’ ‘I did say so, and I say it again,’ returned Scheich Ibrahim; ‘but why do you ask the question? ’ ‘And is this superb pavilion yours also?’ asked Noureddin. Scheich Ibrahim had not expected this question, and felt somewhat embarrassed. ‘If I should say it is not mine,’ thought he, ‘they will ask me immediately how it is possible that I can be master of the garden and not of the pavilion? ’ Therefore, having pretended that the garden was his, he found it necessary to assert the same of the pavilion. ‘My son,’ he replied, ‘the pavilion is not detached from the garden; both of them belong to me.’ ‘Since it is yours,’ replied Noureddin, ‘and you allow us to be your guests to-night, I entreat you to grant us the favour of letting us see the interior; for to judge from its external appearance, it must be beyond measure magnificent.’

“Scheich Ibrahim felt that it would not be civil in him to refuse Noureddin’s request after the handsome way in which the young stranger had treated him. He considered, too, that the caliph, who had not sent him the notice that always preceded a royal visit, would not be there that night; and that, therefore, his guests and himself might safely take their repast in the pavilion. Having, therefore, placed the provisions he had brought upon the first step of the staircase, he went to his apartment to find the key, and, returning with a light, opened the door.

“Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian entered the saloon, which they found so very splendid that they were for a long time wholly engrossed in admiring its riches and beauty. The sofas and ornaments, as well as the pictures, were in the highest degree magnificent; and, besides the lustres which hung at every window, there were between the frames silver branches, each containing a wax taper. Noureddin could not behold these objects without calling to mind the splendour in which he himself had lived, and heaving a sigh of regret.

“In the meantime Scheich Ibrahim brought the provisions, and prepared a table upon one of the sofas; and, now that everything was ready, he sat down to supper with Noureddin and the Beautiful Persian. When they had finished, and had washed their hands, Noureddin opened one of the windows, and calling the Beautiful Persian, said, ‘Come hither and admire with me the charming view, and the beauty of the garden in the light of the moon. Nothing can be more delightful.’ She obeyed, and they together enjoyed the sight, while Scheich Ibrahim was removing the cloth from the table.

“When he had done this, and had returned to his guests, Noureddin asked him if he had nothing in the way of liquor with which he could regale them. ‘Would you like some sherbet?’ said Scheich Ibrahim; ‘I have some that is exquisite; but you know, my son, sherbet is never taken after supper.’ ‘That’s very true,’ replied Noureddin; ‘but it is not sherbet we want. There is, you know, another kind of beverage; I am surprised you don’t understand what I mean.’ ‘You must surely mean wine,’ said Scheich Ibrahim. ‘You have guessed it exactly,’ replied Noureddin. If you have any, you will oblige us much by bringing a bottle; for you know it will pass away the time very agreeably from supper till bed time.’

“ ‘Allah forbid that I should ever touch wine!’ exclaimed the old man, ‘or that I should approach the place where it is kept! A man who, like me, has made the pilgrimage to Mecca

p four times, has renounced wine for the rest of his days.’

“ ‘Still you would do us a great kindness to procure us some,’ returned Noureddin, ‘and, if it will not be disagreeable to you, I will teach you a method of doing so without entering a tavern, or even touching the vessel that contains it.’ ‘I will agree on these conditions,’ returned Scheich Ibrahim; ‘only tell me what I am to do.’

“Noureddin resumed: ‘As we came here we saw an ass tied up at the entrance of your garden. I conclude it to be yours; and, therefore, you ought to make use of it in cases of necessity. Here, take these two pieces of gold; lead your ass with his panniers and proceed towards the first tavern; but do not approach it nearer than you like; give something to the first person who passes by, and beg him to go to the tavern with the ass and procure two pitchers of wine, one for each pannier; then let him lead the ass back to you, after he has paid for the wine with the money which you will give him. You have then nothing to do but to drive the ass before you hither, and we ourselves will take the pitchers out of the panniers. Thus, you see, you will do nothing that can give your conscience the least offence.’

“The two new pieces of gold which Scheich Ibrahim had now received, produced a wonderful effect upon his mind. When Noureddin had finished speaking, he exclaimed, ‘O my son, well do you understand things; without your assistance I could never have imagined any possible means by which I could have procured you wine, without feeling some compunction. ’ He left them to set about his commission, which he executed in a very short time. As soon as he returned Noureddin, descended the steps, drew the pitchers from the panniers, and carried them up into the saloon.