THE THREE APPLES.

SIR ,” said Scheherazade, “the Caliph Haroun Alraschid one day desired his grand vizier Giafar

u to be with him on the following morning. ‘I wish,’ said he, ‘to visit all parts of the city, and to ascertain in what esteem my officers of justice are held. If there be any of whom just complaints are made, we will discharge them, and put others in their places who will give greater satisfaction. If, on the contrary, there be any who are praised, we will reward them according to their deserts.’

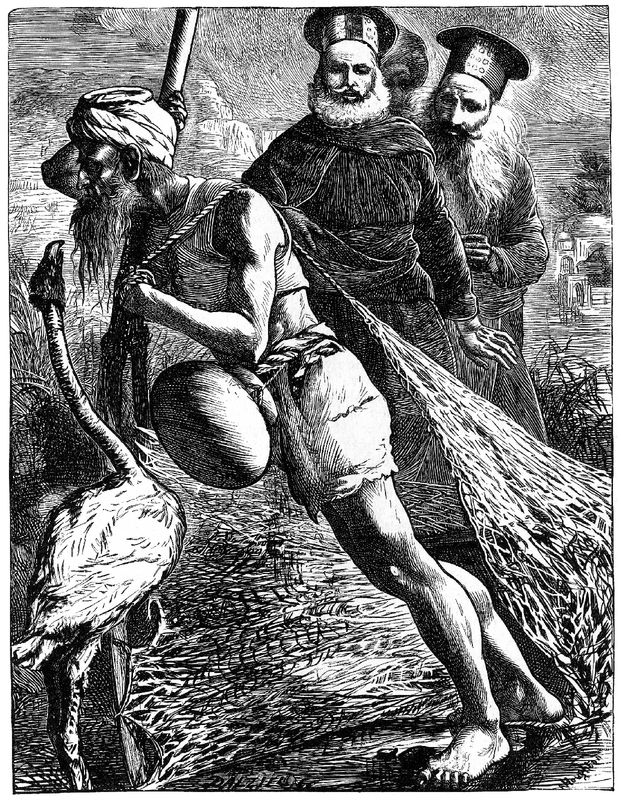

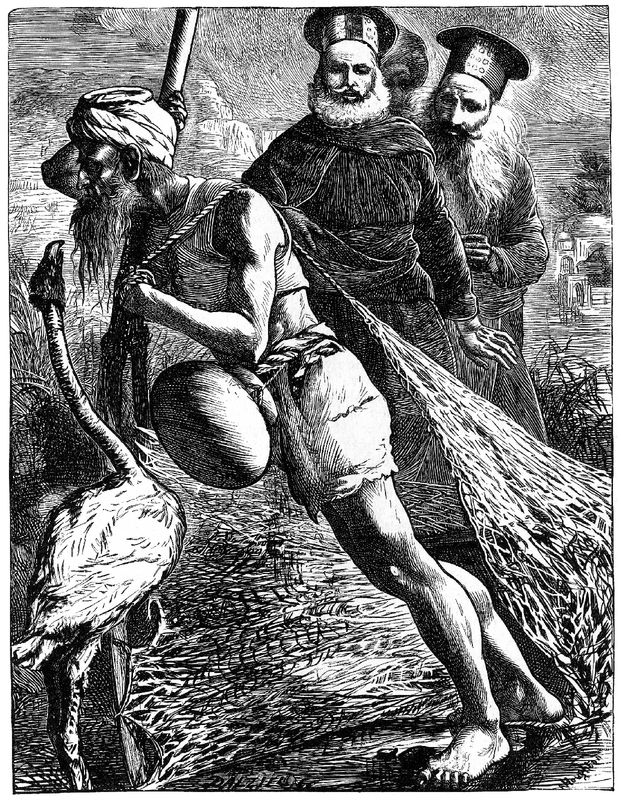

The fisherman drawing his net.

“The grand vizier repaired to the palace at the appointed time. The caliph, Giafar, and Mesrour the chief of the eunuchs, disguised themselves, that they might not be known, and set out together.

“They passed through several squares and many market-places; and as they came into a small street they perceived, by the light of the moon, a man with a white beard, and of tall stature, carrying nets on his head. He had on his arm a basket made of palm-leaves, and in his hand a stick. ‘To judge by this old man’s appearance,’ said the caliph, ‘I should not suppose him rich; let us address him, and question him concerning his lot.’ ‘Good man,’ said the vizier, ‘what art thou?’ ‘My lord,’ replied the old man, ‘I am a fisherman, but the poorest and most miserable of my trade. I went out at noon to go and fish, and from that time till now I have caught nothing; and yet I have a wife and young children, but have nothing wherewith to feed them.’

“The caliph, touched with compassion, said to the fisherman, ‘Wilt thou return, and cast thy nets once more? We will give thee an hundred sequins for what thou bringest up.’ The fisherman, taking the caliph at his word, and forgetting all the troubles of the past day, returned towards the Tigris, in company with him, Giafar, and Mesrour.

“They arrived on the banks of the river. The fisherman cast his nets, and drew out a chest, closely shut and very heavy. The caliph immediately ordered the vizier to count out a hundred sequins to the fisherman, whom he then dismissed. Mesrour took the chest on his shoulders by order of his master, who, anxious to know what it could contain, returned immediately to the palace. On opening the chest, they found a large basket made of palm-leaves, the upper part sewn together with a bit of red worsted. To satisfy the impatience of the caliph, they cut the worsted with a knife, and drew out of the basket a parcel wrapped in a piece of old carpet, and tied with cord. The cord was soon untied and the packet undone, and then they saw, to their horror, the body of a young lady, whiter than snow, and cut into pieces. The caliph’s astonishment at this dismal spectacle cannot be described; but his surprise was quickly changed to anger; and, casting a furious look at the vizier, he cried, ‘Wretch! is this the way you inspect the actions of my people? Murder is committed with impunity under your administration, and my subjects are thrown into the Tigris, that they may rise in vengeance against me on the day of judgment! If you do not speedily revenge the death of this woman by the execution of her murderer, I swear by the holy name of God that I will have you hanged, with forty of your relations.’ ‘Commander of the Faithful,’ replied the grand vizier, ‘I entreat your majesty to grant me time to make proper investigation. ’ ‘I give you three days,’ returned the caliph; ‘look to it.’

“The vizier Giafar returned home in the greatest distress. ‘Alas!’ thought he, ‘how is it possible, in so large and vast a city as Baghdad, to discover a murderer, who no doubt has committed this crime secretly and alone, and has now in all probability fled from the city? Another man in my place might perhaps take any wretch out of prison, and have him executed, to satisfy the caliph; but I will not load my conscience with such a deed; I will rather die than save my life by such means.’

“He ordered the officers of police and justice who were under his command to make strict search for the criminal. They sent out their underlings, and exerted themselves personally in this affair, which concerned them almost as much as the vizier. But all their diligence was fruitless; they could discover no traces that might lead to the murderer’s capture, and the vizier concluded that, unless Heaven interposed in his favour, his death was inevitable.

“On the third day, an officer of the sultan came to the house of the unhappy minister, and summoned him to his master. The vizier obeyed, and when the caliph demanded of him the murderer, he replied, with tears in his eyes, ‘O Commander of the Faithful, I have found no one who could give me any intelligence concerning him.’ The caliph reproached Giafar in the bitterest words, and commanded that he should be hanged before the gates of the palace, together with forty of the Barmecides.

“Whilst the executioners were preparing the gibbets, and the officers went to seize the forty Barmecides at their different houses, a public crier was ordered by the caliph to proclaim, in all the quarters of the city, that whoever wished to have the satisfaction of seeing the execution of the grand vizier Giafar, and forty of his family, the Barmecides, was to repair to the square before the palace.

“When everything was ready, the judge, accompanied by a great number of attendants and guards belonging to the palace, placed the grand vizier and the forty Barmecides each under the gibbet that was destined for him; and a cord was fastened round the neck of each of the prisoners. The people who crowded the square could not behold such a spectacle without feeling pity and shedding tears; for the vizier Giafar and his relations the Barmecides were much beloved for their probity, liberality, and disinterestedness, not only at Baghdad, but throughout the whole empire of the caliph.

“Everything was ready for the execution of the caliph’s cruel order, and the next moment would have seen the death of some of the worthi est inhabitants of the city, when a young man, of comely appearance, and well dressed, pressed through the crowd till he reached the grand vizier. He kissed the captive Giafar’s hand, and exclaimed, ‘Sovereign vizier, chief of the emirs of this court, the refuge of the poor! you are not guilty of the crime for which you are going to suffer; let me expiate the death of the lady who was thrown into the Tigris; I am her murderer: I alone ought to be punished.’

“Although this speech created great joy in the vizier, he nevertheless felt pity for a youth, whose countenance, far from expressing guilt, indicated nobility of soul. He was going to reply, when a tall man of advanced age, who had also pushed through the crowd, came up, and said to the vizier, ‘My lord, do not believe what this young man says to you. I alone am the person that killed the lady who was found in the chest; I alone am worthy of punishment. In the name of God, I conjure you not to confound the innocent with the guilty.’ ‘O my master,’ interrupted the young man, addressing himself to the vizier, ‘I assure you that it was I who committed this wicked action, and that no person in the world is my accomplice.’ ‘Alas! my son,’ resumed the old man, ‘despair has led you hither, and you wish to anticipate your destiny; as for me, I have lived for a long time in this world, and ought to quit it without regret; let me sacrifice my life to save yours. My lord,’ continued he, addressing the vizier, ‘I repeat it—I am the criminal; sentence me to death, and let justice be done.’

“The contest between the old man and the youth obliged the vizier Giafar to bring them before the caliph, with the permission of the commanding officer of justice, who was happy to have an opportunity of obliging him.

“When he came into the presence of the sovereign, he kissed the ground seven times, and then spoke these words: ‘Commander of the Faithful, I bring to you this old man and this youth, each of whom accuses himself as the murderer of the lady.’ The caliph then asked the two men which of them had murdered the lady in so cruel a manner, and then thrown her into the Tigris. The youth assured him that he had committed the deed; the old man maintained that the crime was his. ‘Go,’ said the caliph to the vizier, ‘give orders that both of them be hanged.’ ‘But, Commander of the Faithful,’ replied the vizier, ‘if one only is guilty, it would be unjust to execute the other.’

“At these words the young man cried out, ‘I swear by the great God who has built up the heavens to where they now are, that it is I who killed the lady, who cut her in pieces, and then threw her into the Tigris four days since. As I hope for mercy on the day of judgment, what I say is true; therefore I am the person who is to be punished.’ The caliph was surprised at this solemn oath, which he was inclined to believe, as the old man made no reply. Therefore, turning to the youth, he exclaimed, ‘Un happy wretch! for what reason hast thou committed this detestable crime? What motive canst thou have for coming to offer thyself for execution? ’ ‘Commander of the Faithful,’ returned the young man, ‘if all that has passed between this lady and myself could be written, it would form a history which might be serviceable to mankind.’ ‘Then I command thee to relate it,’ said the caliph. Obedient to the order the young man began his story in these words:—