© National Collection of Aerial Photography(Published through Google Earth)

In 1946, the codebreakers moved from Bletchley Park to Eastcote, a base in north-west London – John Betjeman’s ‘Metro-land’. Despite the pleasant leafy surroundings, William Bodsworth described the Spartan new HQ, seen from above, as ‘shattering’.

© Bletchley Park Trust

Bletchley’s suave Hut 8 veteran Hugh Alexander (much swooned over by female codebreakers) was a crucial figure in the new, regenerated GCHQ – but he continued to pursue his parallel brilliant career in chess.

© Charles Fenno Jacobs/Getty Images

The 1948 Berlin Blockade – Soviet troops ruthlessly starving the city of food and essentials, and Allied airlifts being sent in – proved a tense Cold War test for the codebreakers, and the secret listeners posted throughout Germany.

© Popperfoto/Getty Images

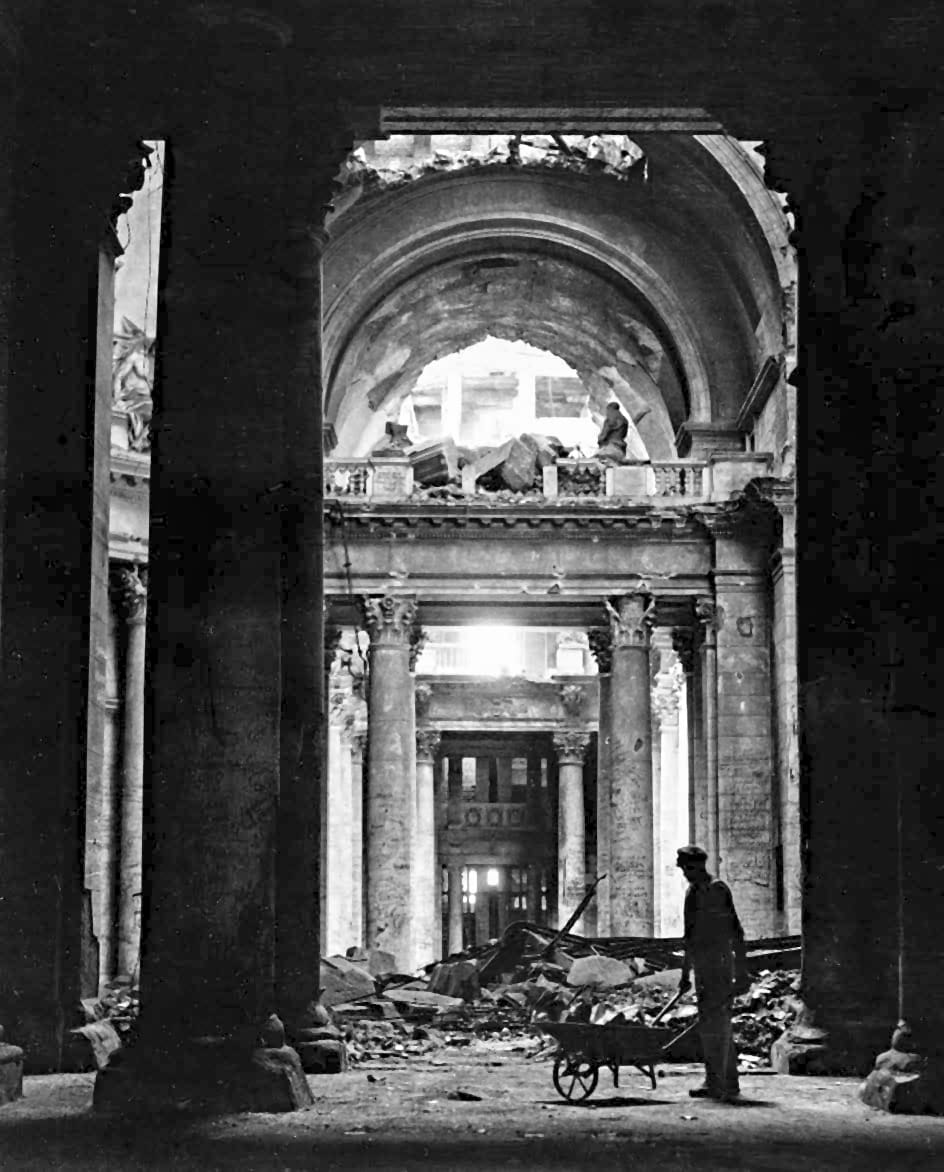

With post-war Germany in ruins – even the grandeur of the Reichstag was destroyed – the codebreakers were in a race to seize advanced Nazi cryptography technology, and also to establish secret bases to intercept and crack Soviet traffic.

© School of Computer Science, University of Manchester

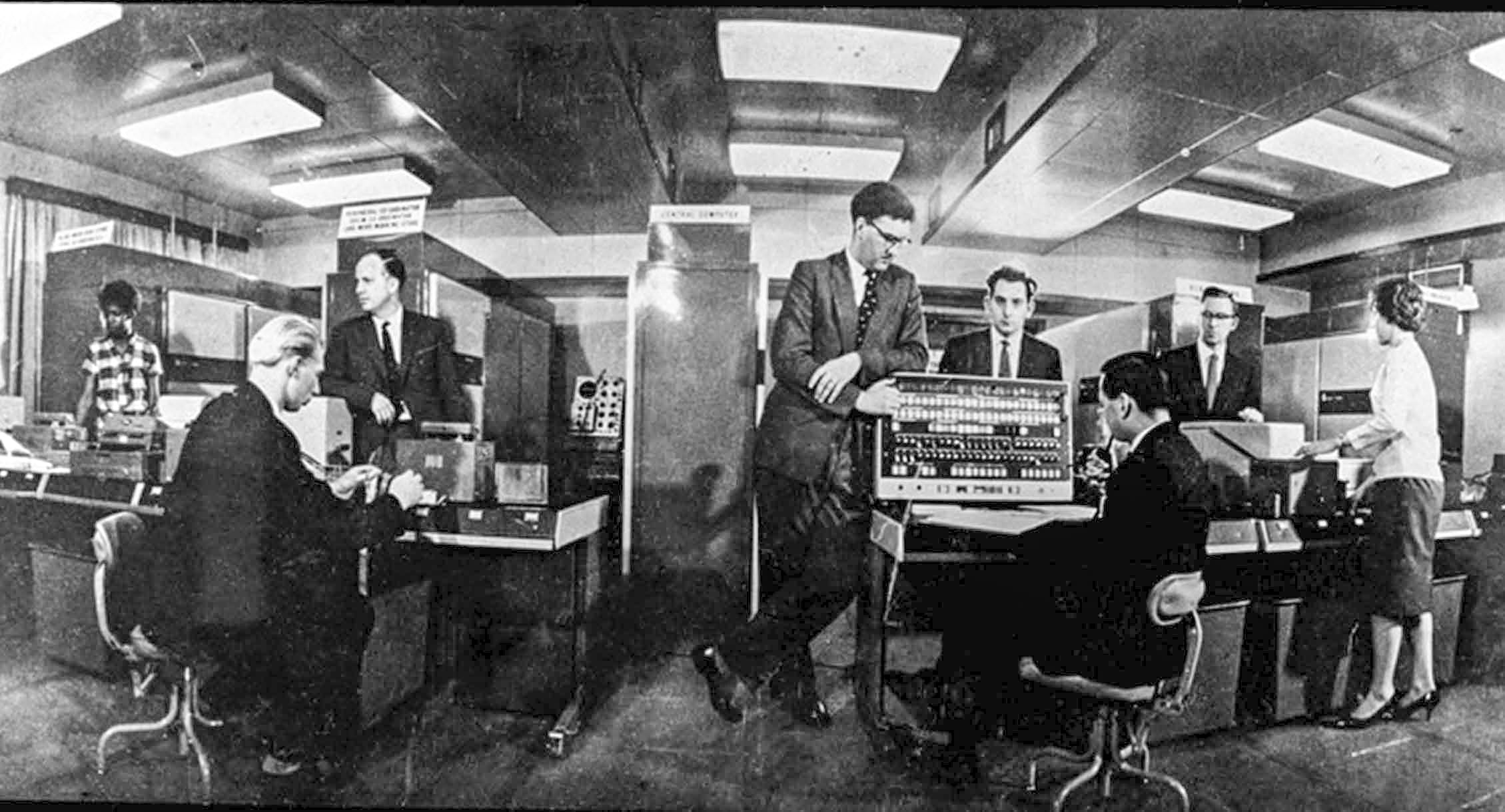

A gleaming new age of computers and codes: Bletchley veteran Professor Max Newman became a post-war computing pioneer at Manchester University, and maintained close links with GCHQ as the Cold War froze deeper.

Crown Copyright, reproduced by permission Director GCHQ

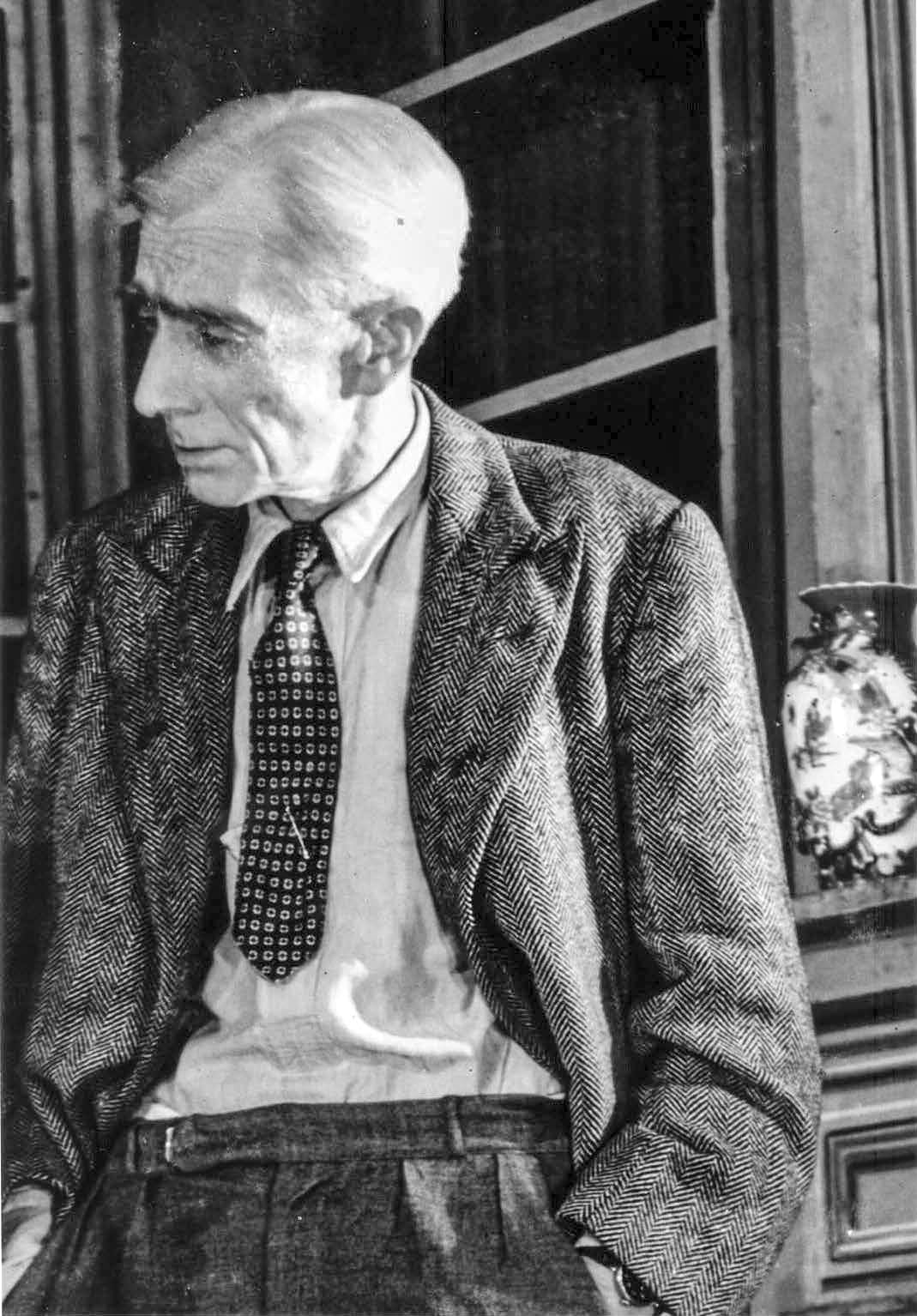

One of the twentieth century’s most pivotal codebreakers, Nigel de Grey, who had decrypted the First World War’s crucial Zimmermann Telegram, bringing the US into that war, was a key post-war architect of the new GCHQ. He had a deeply sardonic wit and an acidic impatience with military brass hats and trades unions alike.

© Martin Sharman [Flickr: Kalense Kid, https://flic.kr/p/9jy8An]

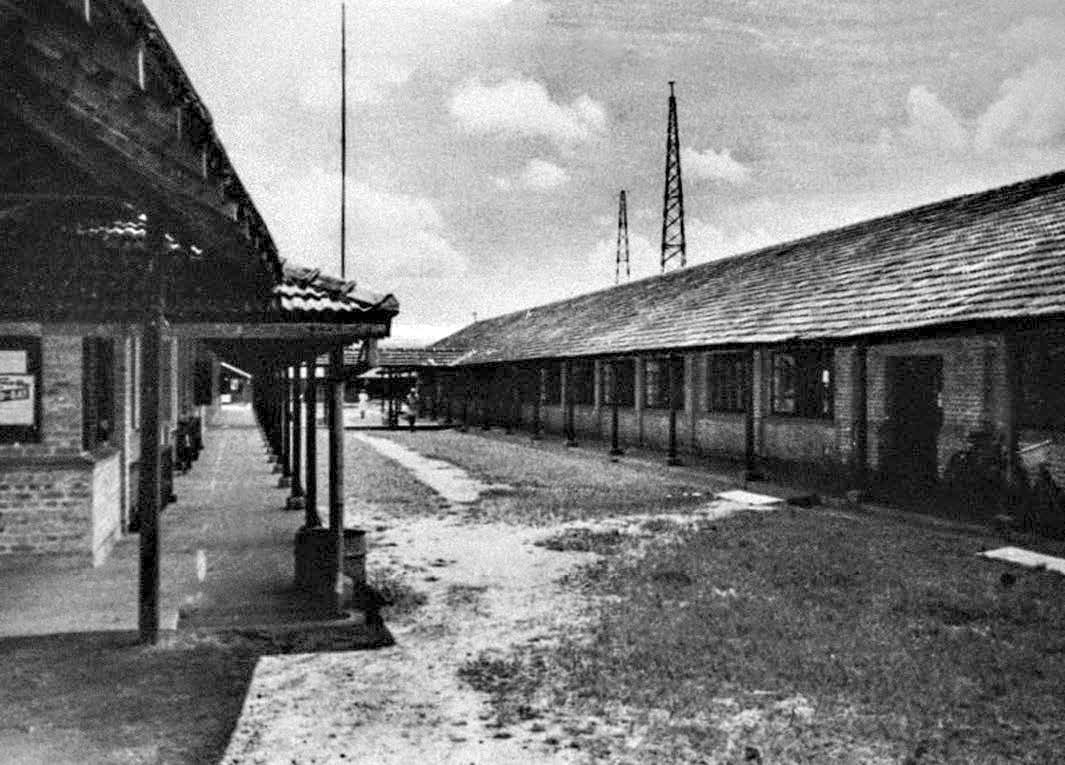

As the British Empire began its speedy and sometimes bloody disintegration, far-flung codebreaking bases such as HMS Anderson in Colombo, Ceylon, lost none of their vital strategic importance, and their secret work went on.

© National Army Museum, London

Post-war National Service pulled radio-mad young men into the realm of secret wireless interception; many were sent out to countries such as Malaya, deep in jungles, monitoring burgeoning unrest and revolt.

Crown Copyright

Wireless interceptors were posted all over the Far East, and many revelled in the amazing new worlds that opened up. Novelist-to-be Alan Sillitoe recalled eerie tropical night shifts with inexplicable snatches of classical music coming through the ether.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Sir Edward Travis, the much-admired – if sometimes bellowing – director of both Bletchley Park and its new post-war incarnation. He ensured that the newly regenerated GCHQ won proper respect from Whitehall and rival secret agencies.

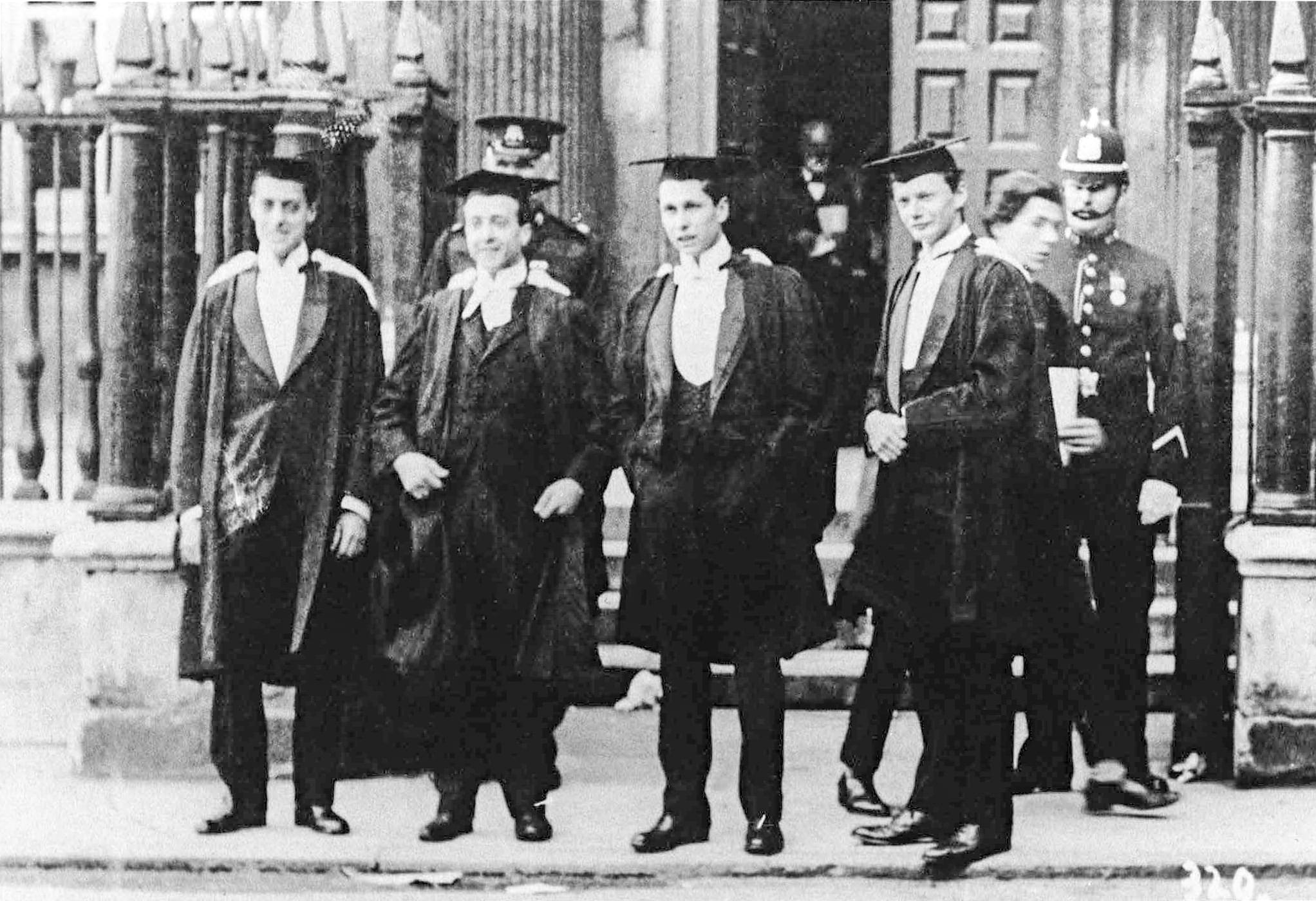

© Kings College Archives, Cambridge

Frank Birch (second from left), another brilliant Bletchley veteran, who went on to help forge the momentous Cold War codebreaking alliance between Britain and the US. This secret life didn’t hinder his love for acting; he appeared in many early television dramas at that time.

© GCHQ

The fierce demands of monitoring the Soviets meant an increase in numbers – and a move for the codebreakers out of Metro-land. There was a site at Cheltenham that had been partly developed for the military during the War which seemed the perfect choice.

© GCHQ

When the codebreakers considered the move from London, other towns – including Oxford and Cambridge – were considered. Cheltenham was rumoured to be a popular choice because of its race-course.

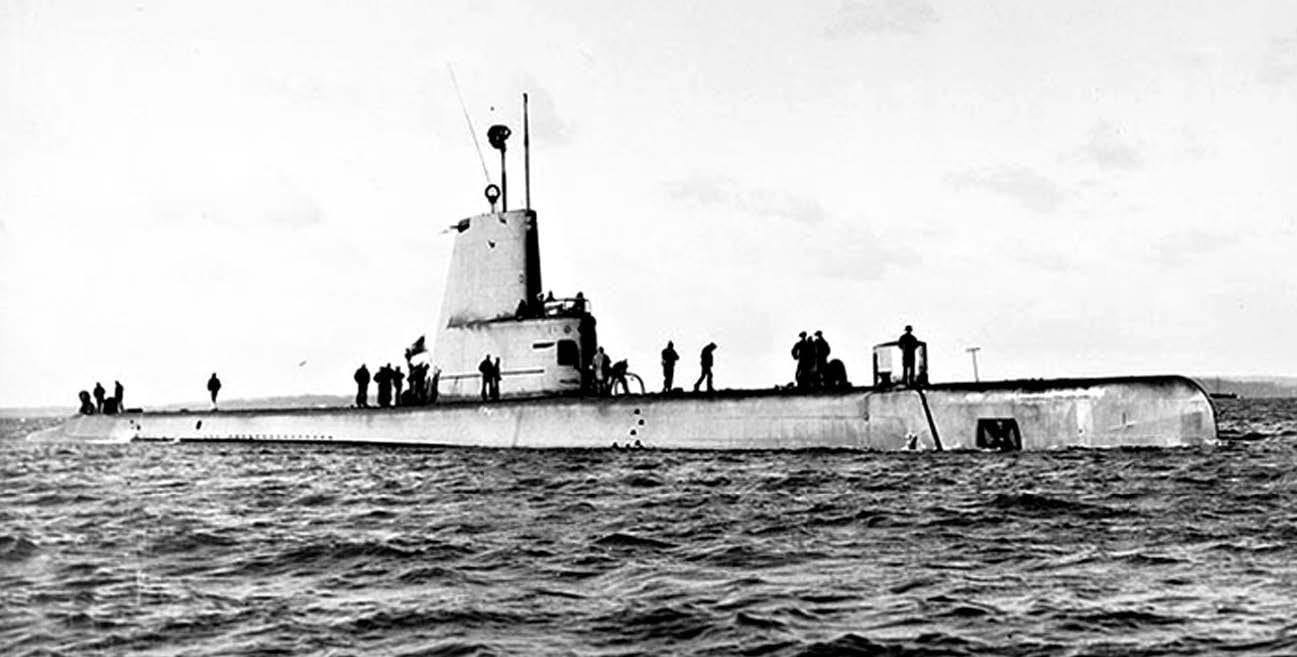

© Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=688136

A new world of ingenious US/UK surveillance innovation was encapsulated by the American submarine USS and its on-board technology; but pursuit of Soviet vessels was hazardous and in the 1950s there was a hideous fiery tragedy at sea.

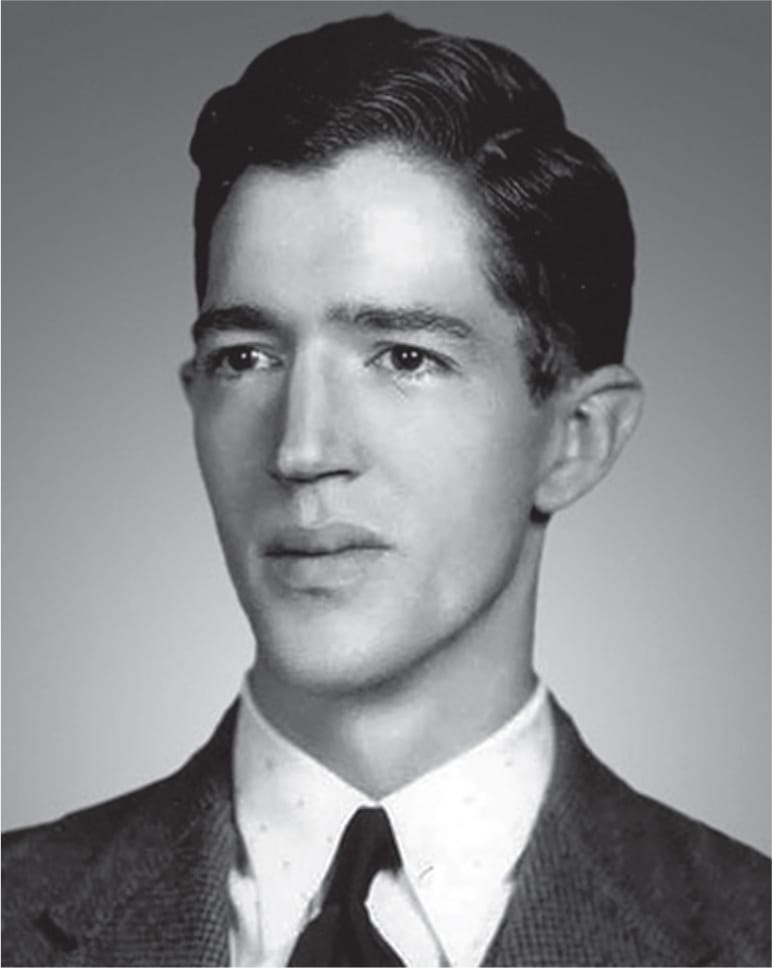

Courtesy of the National Security Agency

The Americans produced some dazzling codebreakers, many of whom came over to work with GCHQ. One such individual was Meredith Gardner, an intensely modest genius, who was partly responsible – by breaking into key Soviet codes – for unmasking the Cambridge Spies.

© Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS VA, 7-ARL,12A--8

America’s answer to Bletchley Park: Arlington Hall in Virginia, not far from Washington DC. It was here, in this crucible of codebreaking, that the activities of atomic spies at Los Alamos and other double agents were uncovered.

© Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS VA, 7-ARL,12--1

The men and women of Arlington Hall and GCHQ worked together incredibly closely; like the UK codebreakers, Arlington Hall’s experts were drawn from all over, such as schoolteacher Gene Grabeel and Brooklyn prodigy Solomon Kullback. The relationship between the US and UK was – in this instance – genuinely special.

© AP/Press Association Images

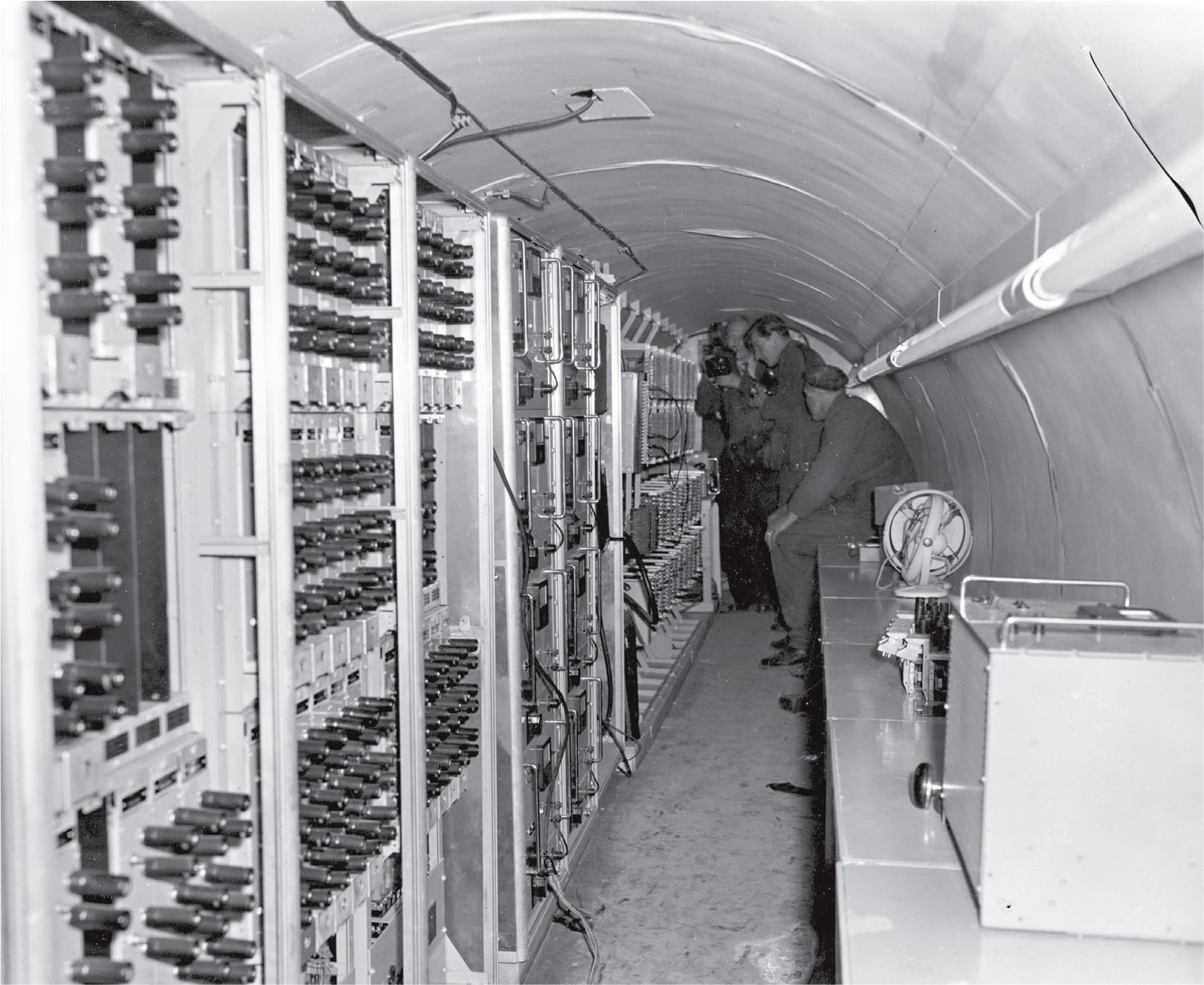

The Berlin tunnel – a terrific ruse to tap into Soviet communications – had an equally ingenious forerunner in Vienna, when young wireless interceptors such as diplomat-to-be Sir Rodric Braithwaite entered secret passages through false shop fronts.

© Gnter Bratke/DPA/PA Images

Unfortunately, thanks to traitor George Blake, the Soviets knew all about the Berlin surveillance tunnel; they staged a serendipitous ‘discovery’ of the British interception equipment in 1956 in order not to give away their double agent.