“Fix it, Baby, fix it.”

Sammie stopped hitting her tennis ball against the garage and surveyed the scene with her ten-year-old eyes. She gave a very quiet too-adult sigh.

Her mother sat limply on the back stoop, her hand dangling, the jelly glass smashed inches below her hand. The smell of rum slightly overpowered the smell of cola.

Sammie pushed through the screen door and returned with the broom and dustpan. As she swept sparkling glass bits out of the shaggy grass, her mother said, “No, Baby, not yet. Get me another drink first.”

When her mother had a fresh glass in hand and Sammie had rinsed off the stoop, her mother put her arm out to the side and said, “Come here, Baby.”

Sammie hated to be close to her mother when she reeked of rum and her body went floppy. But Sammie knew from long experience that if she resisted, her mother would swap her teariness for fury and hound her until she complied anyway.

She edged into her mother’s side, which was damp from humidity and sweat, trying to keep a bit of air between them, but her mother clamped her like a vise. “I love you, Baby. You are my precious girl. Precious, precious.”

Now fast-forward twenty-five years to observe the childhood dilemma imposed on an adult situation (and its effect on a friendship). As Voula and thirty-five-year-old Sammie were taking a walk, Voula said, “It’s hard for me to say this, Sammie, but I’m getting tired of waiting for you. You were twenty minutes late today. Last week you were fifteen, and the week before you cancelled just as I was walking out the door. It makes me feel as if our get-togethers aren’t that important to you, and I’m getting angry that my time isn’t respected.”

“I am such a screwup,” Sammie replied in a contrite voice. “I know your time is valuable, and our friendship matters a lot to me. I just can’t get myself to keep from doing that one extra thing on the way out the door, and then it leads to another, and I suddenly realize I’m late.”

“We’ve talked about this before,” Voula said, “but you aren’t doing anything different. You say one thing and do another, and not just in this situation. There are things you could do. You could set an alarm to alert yourself. You could program your computer to flash a message.”

Voula continued, “I want you to hear that this matters to me. Partly I don’t have time to throw away. But even more, I feel blown off when I don’t see you taking any measures to make it work out. Next week, I’m waiting five minutes, and then I’m walking whether you are here are not.”

“Okay, fair enough. It’s a good idea to set an alarm.”

Voula gave an explosive sigh. “I feel like a harpy and I don’t want to feel like this, but I’m angry. It seems to me that if you valued how upset I was the last couple of times we talked about this, you could have been setting an alarm already.”

“You’re right. I could have thought of it. I got overwhelmed, feeling like such a loser, and then just checked out on the whole incident.”

Voula chose not to say more because it would have seemed like a threat if she’d put her feelings into words, but she knew that if Sammie didn’t follow through, it was going to cause her to back off from their relationship.

Sammie had forgotten the previous incidents and hadn’t acted on them because each time she had fallen so deeply into shame that she’d drowned her memories in a sugar binge.

Sammie had said many times, and deeply believed, that friendship was exceedingly important to her. This was true. When Sammie was fully present, no one doubted her love or her sincerity when she offered her friendship. But over and over, her behavior did not match either her words or her passionate promises.

Sammie was devastated when she lost a friend and couldn’t understand it. She was committed to her friends and fervent in her regard for them. From her point of view, their periodic exodus made no sense. She couldn’t fathom why a friend would throw away something as dear as friendship for something so trivial as lateness.

Friends gave up on Sammie, but not just because of lateness or broken commitments. They also quit because they got tired of trying to handle confusion they didn’t understand.

When a friend’s behavior doesn’t match her words, it is confusing and even hurtful.

Sammie created a dilemma for her friends because when she said she would not be late again, her energy was completely in alignment with her words. She was entirely believable because she herself believed and meant what she said.

But after such a convincing promise, when Sammie showed up quite late again, that combination created dissonance for her friends. Did Sammie know she created dissonance in her friends? No. Did she know she had an internal conflict? No. Was there a consequence for someone? Yes, for her friends, until they protected themselves by leaving—and for Sammie after they left. Eventually, even her fervent promises and plausible excuses wouldn’t cut it anymore.

Sammie exhibited a common theme among misery addicts: a longing for intimacy matched by a fear of intimacy.

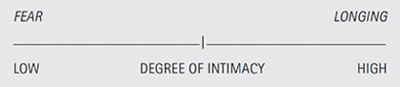

If we draw a line with longing for intimacy at one end and fear of it at the other, there’s some point at which we come to a balance for ourselves, where our longing is tempered by our fear.

This point comes close to the amount of intimacy we can tolerate without getting so afraid that we must do something to distance ourselves from the other person.

When Sammie was with a friend, the reality of the person in front of her dissipated her fear, and she could fully participate. But before meeting with a friend, a nameless, unfelt fear of getting hurt by intimacy led her to get distracted by various tasks. When she was at home or work, the reality of that friend receded, to be replaced with a vague image of a loved one who took instead of gave and who forced her into unpleasant contact. This image was not conscious but stirred deep inside of her.

Sammie felt this dissonance and did not know it, and she passed on this dissonance to her friends. They did not comprehend or name it, but they experienced it, and eventually it eroded their relationships with Sammie.

If we go back in time, we can see that Sammie’s mother created dissonance for Sammie. She made her daughter fix problems she herself created; she pretended to give while taking; and she forced unpleasant physical contact in the name of love. Sammie grew up with an emptiness, with a yearning for profound connection with others. She also had embedded in her, like a time bomb, a profound fear of being engulfed and used in the name of love. This conflict flowered in her behavior and set the course of her relationships.

The following theme, and its many variations, can be found throughout the lives of misery addicts: a longing for success and unconscious acts that keep it at bay. The misery addict yearns for happiness and sets up sadness, wants financial security and repeatedly sabotages financial plans, desires family but keeps potential family at a distance, wants meaningful work but keeps busy with work that won’t ever go in the desired direction. Thus the longing for happiness never shrinks, and the efforts to attain it rarely succeed.