Somewhere in the east: early morning: set off at dawn. Travel round in front of the sun, steal a day’s march on him. Keep it up for ever, never grow a day older technically.

—LEONARD BLOOM in Ulysses1

PETRUCHIO: It shall be what o’clock I say it is.

HORTENSIO: Why, so this gallant will command the sun.

—SHAKESPEARE,

The Taming of the Shrew2

IN THE EARLY 1960s, MY FATHER RETIRED FROM HIS FAMILY FIRM to run a pub in Cornwall, in the far southwest of England, and during the school holidays I would work alongside him. Twice each day, at 2:30 in the afternoon and again at 11:00 in the evening—in keeping with the licensing laws whereby pubs had to close first for three hours, then again for nearly twelve hours until reopening at 10:30 the following morning—he would intone in his basso profundo: “Time, gentlemen, please!” It was a peculiar social ritual, a polite command to stop drinking that had the feel of a teleological pronouncement. Patrons would know they had a minute or two to drink up. In contrast to that sixty seconds of silence imposed by my English teacher at the end of his classes, which we’d so longed to be over, the hardened locals stretched out every last moment of tippling as long as they could, for the announcement was never welcome. As Oliver St. John Gogarty (1878–1957), the Irish poet who inspired the character of Buck Mulligan in Ulysses, wrote:

No wonder stars are winking

No wonder heaven mocks

At men who cease from drinking

Good booze because of clocks!

In this grim pantomime

Did fiend or man first blether

“Time, Gentlemen, Time!”*

“Time” has continued to vex mankind since the beginning of … well, the word is difficult to avoid. Its complexities feed on mankind’s subjective experiences of time versus our objective measurement, and the impossibility of ever reconciling the two. Anthony Burgess hints at this in his essay “Thoughts on Time”:

In the first great flush of the establishment of universal public time [Greenwich Mean reckoning], there were certain works of the imagination which … said something about the double reality of time. Oscar Wilde wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray, in which the hero transfers public time, as well as public morality, to his portrait while himself residing in a private time which is motionless.… The experience of time during both the First and Second World Wars was of a new kind to the average participant.… The start of battles had to rely on public time, but soldiers lived on inner time—the eternities of apprehension that were really only a minute long, the deserts of boredom, the terror that was outside time.3

Time as experienced subjectively may indeed be mysterious: in the Iliad, its quality has one value for the victors, another for the vanquished. Saint Augustine said sourly that he knew what time was until he was asked to explain it. But no matter how it is parsed, it is the Sun that determines time, and our employment of that guiding star to monitor time’s passing has been the most pervasive of all the ways in which civilizations harness the Sun.

It has ever been critical for two groups—astronomers and navigators—to measure time with precision; but throughout the Christian world it has been the Church that has provided the main impetus toward timekeeping. Much the same is true for Muslims and Jews; Islam requires its faithful to pray five times a day, Judaism three. Christians would pray according to the movements of the heavens, and it was Saint Benedict who, in his Rule of A.D. 530, laid down exact times for devotion: Matins, Lauds, Prime (first), Tierce or Terce (third), Sext (sixth), None (the ninth hour after sunrise, which survives, though three hours backtimed, as noon), Vespers, and Compline. Lauds and Vespers, the services of sunrise and sunset, are specifically Sun-related, while the others are linked to set hours. This timetable was widely adopted, so much so that Pope Sabinianus (605-6) proclaimed that church bells should be rung to mark the passing of the hours. In the years that followed, a large number of forms of civil life came to be regulated by time. “Punctuality,” writes Kevin Jackson, “became a new obsession, and constant research into timekeeping mechanisms eventually resulted in the making of the clock.”4

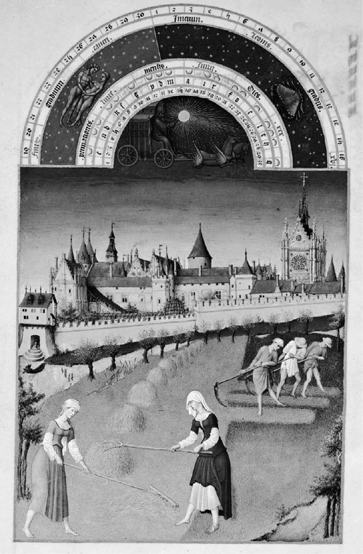

In the later Middle Ages, from roughly 1270 to 1520, by far the bestselling volume throughout Europe was not the Bible but The Book of Hours, a guide to Benedict’s Rule. During these years, the practice was maintained of defining one hour as the twelfth part of the day or the night, so that in the summer, daytime hours were longer than those of darkness, the opposite being true in the winter—a custom ending only when the newly invented mechanical clock, with its uniform motion duplicating that of the heavens, gradually made people familiar with the “mean solar” way of measuring used by astronomers. Mechanical clocks driven by weights and gears would seem to have been the invention of an eleventh-century Arab engineer and were introduced into England around 1270 in experimental form; the first clocks in regular use in Europe and for which we have sure evidence were those made by Roger Stoke for Norwich Cathedral (1321-25), and by Giovanni de’ Dondi of Padua, whose one-yard-high construction of 1364, with astrolabe and calendar dials and indicators for the Sun, Moon, and planets, provided a continuous display of the major elements of the (Earth-centered) solar system and of the legal, religious, and civil calendars. These clocks were made not to show the time but rather to sound it. The very word “clock” comes from the Latin word for “bell,” clocca, and this hour-checking machine was for years also known as a horologue (“hour teller”)—although medieval striking clocks were thoughtfully designed to remain silent at night. This device, Daniel Boorstin notes, was

An illuminated manuscript page from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1412-16) by the three brothers Limbourg, showing June, a curious time for haymaking, with the Hôtel de Nesle, the duke’s Parisian residence, in the background. The book is a collection of sacred texts for each liturgical hour of the day. Illu(21.1)

a new kind of public utility, offering a service each citizen could not afford to provide himself. People unwittingly recognized the new era when, noting the time of day or night, they said it was nine “o’clock”—a time “of the clock.” When Shakespeare’s characters mentioned the time, “of the clock,” they recalled the hour they had heard last struck.5

In 1504, after a brawl in which a man was killed, the Nuremberg locksmith Peter Henlein (1479–1542) sought sanctuary in a monastery, staying there for several years, during which time he invented a portable clock—the first watch—devised, as the Nuremberg Chronicles of 1511 record, “with very many wheels, and these horologia, in any position and without any weight, both indicate and strike for forty hours, even when carried on the breast and in the purse.”6

Yet until well into that century, people had to set their timepieces according to the shifting sunrise each day, and stop to adjust them every time they were caught running fast or slow. The expected accuracy was no better than to the nearest fifteen minutes—Tycho Brahe’s clock, typically, had just an hour hand. Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642) was showing off his collection of clocks when a visitor knocked two onto the floor. Quite undismayed, the cardinal observed, “That’s the first time they have both gone off together.”

Toward the end of the sixteenth century, the Swiss clock maker Jost Bürgi constructed a piece that could mark seconds as well as minutes; “but that,” observes Lisa Jardine, “was a one-off, difficult to reproduce, and reliable seconds’ measurement had to wait another hundred years.”7 That is probably an exaggeration: by 1670, minute hands were common, and the average error of the best timepieces had been reduced to about ten seconds a day. (The noun “minute,” derived from pars minuta prima, “the first tiny part,” had entered the English language in the 1660s; “second” comes from pars minuta secunda.) By 1680 it was common for both minute and second hands to appear.

Punctuality and timekeeping soon became the fashion, even fetish: Louis XIV had not one clock maker but four, who, along with their armory of devices, accompanied him on his “progresses.” Courtiers at Versailles were expected to order their days by the fixed times of the Sun King’s rising, and of his prayers, council meetings, meals, walks, hunts, concerts. One of the six classes of French nobility was the noblesse de cloche—“nobility of the bell”—drawn largely from the mayors of large towns, the bell being the embodiment of municipal authority. Timepieces were exact enough that philosophers from Descartes to Paley took to using clocks as a metaphor for the perfection of the divine creation. Lilliput’s commissioners report on Lemuel Gulliver’s watch: “We think it is his God, because he consults it all the time.” With both Frederick the Great (1712–1786) and that hero of Trafalgar and Navarino, Admiral Codrington (1770–1851), having their pocket watches smashed by enemy fire, it seemed the mark of eminent commanders “up at the sharp end” to have their accessories thus shattered.

In order to meet the new demand for individual timepieces (not only watches, but clocks small enough to fit into a modest house or a craftsman’s workshop), clock makers were forced to become pioneers in the creation of scientific instruments: their products, for instance, required precision screws, which in turn necessitated the improvement of the metal lathe. The mechanical revolution of the nineteenth century was the result in large part of ordinary people’s wish to tell the time for themselves. And yet there continued to be holdouts even into the twentieth: Virginia Woolf, in Mrs. Dalloway, lets out almost a cry of pain at the ubiquity of the clock:

Shredding and slicing, dividing and subdividing, the clocks of Harley Street nibbled at the June day, counseled submission, upheld authority, and pointed out in chorus the supreme advantages of a sense of proportion, until the mounds of time were so far diminished that a commercial clock, suspended above a shop in Oxford Street, announced, genially and fraternally, as if it were a pleasure to Messrs. Rigby and Lowndes to give the information gratis, that it was half-past one.8

When in 1834 a clock was commissioned as part of the rebuilding of the fire-gutted Palace of Westminster, the government called for “a noble clock, indeed a king of clocks, the biggest the world has ever seen, within sight and sound of the throbbing heart of London.” The astronomer royal further insisted that it should be accurate to within a second. The outcome was Big Ben (strictly speaking, a bell), finally completed in 1859.9

But once people could tell the “exact” time, what time were they telling? There were so many to choose from. In 1848, the United Kingdom became the first country in the world to standardize time across its entire territory—to the signal of the Greenwich Observatory (with Dublin Mean Time set just over twenty-five minutes behind). That year saw the publication of Dombey and Son, in which a distraught Mr. Dombey complains, “There was even a railway time observed in clocks, as if the sun itself had given in.” In 1890, Dr. Watson records traveling by train with Sherlock Holmes to a case in the West Country and being startled by the master’s gauging minute fluctuations in the train’s velocity by timing the telegraph poles, set at standard sixty-yard intervals, as they flashed past their window, with the train acting as the Sun, the poles as longitudes—a powerful image of the way in which the concept of the standardization of time had insinuated itself into people’s consciousness.

The calendar used by an Inuk hunter in the 1920s, following the introduction of Christianity to the Canadian eastern Arctic: days of the week are represented by straight strokes, Sundays by Xs. The calendar was also used as a hunting tally, including counts of caribou, fish, seals, walrus, and polar bears. Illu(21.2)

Not everyone’s, of course. Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) once arrived exceptionally late for a dinner, his hostess pointing angrily at the clock on the wall and exclaiming, “Mr. Wilde, are you aware what the time is?” “My dear lady,” Wilde replied, “pray tell me, how can that nasty little machine possibly know what the great golden sun is up to?” But it did.10

Einstein, of course, tells us there is no such thing as absolute time: salutary to recall that the office where he worked for so long was a clearinghouse for patents on the synchronization of clocks. And he himself recalled: “At the time when I was establishing how clocks functioned, I was finding the utmost difficulty in keeping a clock in my room.”*

While the Sun appeared to have been replaced, in fact it continued to hold sway throughout the civilized world. Even by the mid-nineteenth century, the towns and cities of most countries still had individual Sun-based systems of timekeeping. Every French city, for instance, held to its own local time, taken from reading the Sun at its equally local zenith. Time bowed to space; there was nothing God-given in the starting point of a second, or a minute, or an hour. The result was that the prospect of a globe united by the telegraph, fast trains, and steamships had so far been stalled, because the spinning, angled Earth and the apparently moving Sun made nonsense of the idea of universal time. The clock on the wall told the hour for the family, the town hall clock that for the citizenry; but on the other side of the hill the clocks were strangers, and the imposition of universal time standards might even be dangerous: Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke (1800–1891), head of the Prussian, then of the German, army for nearly thirty years, lobbied for a unitary time system for Germany as an aid to making the trains run on time so that its troops might be mobilized more effectively, but this was opposed by those who feared that an integrated rail system would provoke Russia to invade. Nevertheless, it was becoming obvious that uniformity could not be put off indefinitely. “Societies were moving faster than their ability to measure,” as the historian Clark Blaise puts it.13 Writing of the First World War, when wristwatches came into common use (they were much favored by sentries), Burgess says:

It was a war of railway timetables. For the first engagements in August 1914, about two million Frenchmen were deployed in 4,278 trains, and only nineteen ran late. The wristwatch, which before the war had been considered effeminate, became the badge of masculine leadership. “Synchronize your watches.” And then over the top.14

IN THE UNITED STATES, the same problem that had bedeviled the rest of the world was troubling individual states. Following the Civil War, railroad expansion had been prodigious. In the forty years after 1860 (by which year the United States already had the world’s largest railroad system), the amount of train track that had been laid down multiplied sixfold. By the turn of the century, nearly every town of any size had its own railway station, if not several. However, as in most of Europe, the reckoning of time was a local matter, set by local noon, which, at the latitude of New York, is about one minute later for each eleven miles one travels westward. Noon in New York was 11:55 a.m. in Philadelphia, 11:47 in Washington, 11:35 in Pittsburgh. Illinois used twenty-seven different time regions, Wisconsin thirty-eight. There were 144 official times in North America, and a traveler in the 1870s going from the District of Columbia to San Francisco, had he set his watch in every town through which he passed, would have had to adjust it more than two hundred times. If a passenger wondered when he might arrive at his final destination, he had to know the time standard of the railroad that was taking him there and make the proper conversion to the local times at his boarding and at his eventual descent. Two cities, set a hundred miles apart, maintained a ten-minute temporal separation, even though a train could cover that distance in less than two hours—so which town’s time was “official”? The train itself might have set out from a city five hundred miles away, so who “owned” the time—the towns along the route, the passengers, or the railroad company? No wonder that Wilde noted that the chief occupation of a typical American was “catching trains.” He visited the States in 1882; one wonders how often he missed his connection.

When people had traveled no faster than the speed of a horse, none of these considerations came into play, but in a railway-framed economy, scheduling was a nightmare. As Blaise writes, “It was the slow increase in speed and power—the fusion of rails and steam—that undermined the standards of horse- and sail-power and, eventually, the sun itself in measuring time.” That quotation comes from Blaise’s biography of the enterprising nineteenth-century Canadian Sandford Fleming, who in June 1876 happened to miss his train in Bandoran (set on the main Irish rail line between Londonderry and Sligo) because the timetable he had consulted had the misprint “5:35 p.m.” for “5:35 a.m.,” condemning him to wait for sixteen hours.15 Fleming was, among other things, the chief engineer of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and his “monumental vexation” at this delay inflamed a desire to number the hours from one to twenty-four. “Why should modern societies adhere to ante meridiem and post meridiem, why double-count the hours, one to twelve, twice a day? [Hours] ought not to be considered hours in the ordinary sense, but simply twenty-fourth parts of the mean time occupied in the diurnal revolution of the Earth.” He would make it his mission to bring about a twenty-four-hour clock by which 5:35 P.M. would become 17:35 H. On further reflection, he set himself the much greater task of relating all time zones worldwide to their relationship to longitude, and of introducing “terrestrial, non-local” time.*

Standard time was the best gauge in the world: it would convert celestial motion to civic time. By 1880, England had been on standard time for more than thirty years, reform having started with the railways; why not America? Because the U.S. Congress, fearing a municipal uproar if it initiated change, had procrastinated, and the railroad industry, though well aware of the negative impact of a lack of standardization on its profits, dithered, too. From 1869 on, this question was debated, until at last popular discontent forced the railroad barons’ hand: as of Sunday, November 18, 1883, they bypassed Congress and adopted the Greenwich system, dividing the country into four zones—Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific—with noon falling an hour later in each. That day came to be known as “the Sunday of Two Noons,” since towns along the eastern edge of each new time belt had to turn their clocks back half an hour, creating a second midday, in order to mesh with those closer to the western edge of the same belt. Within a few years, this system became standard, but not without considerable bitterness, and some towns, such as Bangor, Maine, and Savannah, Georgia, still would not cooperate, from either religious principle or stubbornness. Detroit, perched on the crack between the Eastern and Central time zones, could not make up its mind, so that for many years its inhabitants had to ascertain, in making appointments, “Is that solar, train, or city time?” Congress itself did not ratify standard time until forced to do so by war in 1918.

As the historian Mark Smith records, “the telegraph, not the Sun, now communicated time to a temporarily unified nation and, in the process, helped pave the way for the globalization of abstracted, decontextualized world time.”16 Similarly, people were coming to accept that if a calendar were to serve a practical, global use, all dates had to be interpreted through a solar dateline. The question was, Where would that dateline be?* In 1884 twenty-five countries sent representatives to a conference in Washington, D.C. Eleven national meridians (through St. Petersburg, Berlin, Rome, Paris, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Greenwich, Cádiz, Lisbon, Rio, and Tokyo), as well as additional contenders fixed on Jerusalem, the pyramids of Giza, Pisa (to honor Galileo), the Naval Observatory in Washington, and the Azores—the original point of definition for the age of exploration—competed for primacy. The French, represented by their chief of mission and by the great astronomer Jules-César Janssen, were intransigent, insisting (without much evidence) that their ligne sacrée was a better scientific choice.

Fleming argued for a notional clock set 180 degrees from Greenwich, which would fall in the middle of the Pacific, thus bypassing national sensibilities but still making use of Greenwich, though without involving England; but every longitudinal meridian touches land at some point in its arc, and were Fleming’s solution to be adopted, England would be split every noon between two days. His proposal soon foundered, and the debate ended only when Sir George Airy, Britain’s irascible astronomer royal, wrote that the prime meridian “must be that of Greenwich, for the navigation of almost the whole world [even then, 90 percent] depends on calculations founded on that of Greenwich.” France abstained from voting, and true to its delegates’ defiance, “Greenwich” has never appeared on any of its charts. (By pure coincidence, the anarchist who tried to blow up the observatory in 1894 was French.) Once the vote came through, the meridian was moved from the famous obelisk on Pole Hill to a point nineteen feet farther east. Sundial time was thereby banished, and a sophisticated abstraction rose to take its place.

And so in 1884 the Earth was sliced into twenty-four time zones, each an hour apart, with eastbound travelers adding successive hours, westbound ones losing them. Of course, there has to come a moment—which happens to confront us in the western Pacific—when the logic of the system subtracts a day from eastbound travelers and gives one to those heading west (Verne’s Phileas Fogg learns this just in time to win his bet in Around the World in Eighty Days). One by one, countries adopted Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)—even France, in 1911. However, in 1972, the French, still unhappy at what they perceived as Britain’s unjustified supremacy, carried a resolution at the United Nations to put GMT alongside Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC—to be regulated by a signal from Paris (naturally). While GMT is reckoned by the Earth’s rotation and celestial measurements, UTC is set by cesium-beam atomic clocks, which are less accurate but easier to consult.* In point of fact, the two systems are rarely more than a second apart, as UTC is augmented with leap seconds to compensate for the Earth’s decelerating rotation.

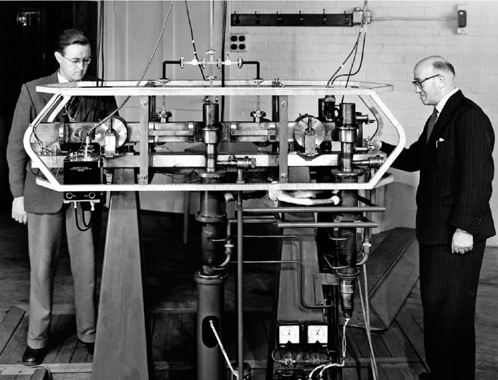

Physicists Jack Perry and Louis Essen adjusting a cesium-beam atomic clock, which they developed in 1955. One second is about 9,193 million oscillations. This clock led to the replacement of the astronomical second with the atomic second as the standard unit of time. Illu(21.3)

THOSE WHO SOUGHT to meddle with the Sun for their own purposes and pleasures were not finished: saving daylight was next. This was a project that dated back to Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), who, on April 26, 1784, while serving as U.S. minister to France, proposed (at the age of seventy-eight and in a moment of whimsy) that Parisians conserve energy (in the form of candlewax and tallow) by rising with the Sun rather than sleeping in with their shutters closed against the day.

The idea never caught on, and more than a century would pass before it would find a receptive audience. Then, in July 1907, the successful London builder William Willett (1857–1915), a keen golfer and horseman, self-published The Waste of Daylight, in which he argued that more people should enjoy the early morning sunshine as he did, and complained about how annoying it was to have to abandon a game of golf because of fading light. Might clocks be shifted forward or backward by twenty minutes on four successive weekends, to make the change easier? It was not just a question for sports enthusiasts:

Everyone appreciates the long light evenings. Everyone laments their shrinkage as the days grow shorter, and nearly everyone has given utterance to a regret that the clear light of early mornings, during Spring and Summer months, is so seldom seen or used.18

Scientists and astronomers were divided on the question, although the press chirped, “Will the chickens know what time to go to bed?” and the editors of Nature ridiculed the idea by equating the time change with the artificial elevation of thermometer readings:

It would be more reasonable to change the readings of a thermometer at a particular season than to alter the time shown on the clock … to increase the readings of thermometers by 10° during the winter months, so that 32°F shall be 42°F. One temperature can be called another just as easily as 2 a.m. can be expressed as 3 a.m.; but the change of name in neither case causes a change of condition.19

But Willett was not easily put off, and within two years a Daylight Saving Bill had been drafted, finally achieving passage as a wartime economy measure in 1916. Earlier that year the Germans had already passed such a law, hoping it would help them conserve fuel and allow factory workers on the evening shifts to work without artificial light. Willett himself had died the previous year; but his neighbors erected a handsome memorial to him—a sundial, positioned to read an hour in advance of the time on any ordinary face.

The 1916 law was made permanent throughout Britain in 1925. America had passed a similar measure in 1916, too, but it proved so unpopular that Congress had to repeal it three years later. (Farmers, whom the measure was designed to help, hated DST, since they had to wake with the Sun no matter what time their clock said and were thus inconvenienced by having to change their schedule to sell their crops to people who observed the new system.) Then in 1922, President Harding issued an executive order mandating that all federal employees start work at 8 A.M. rather than at 9. Private employers could do as they pleased. The result was chaos, as some trains, buses, theaters, and retailers shifted their hours and others did not. Washingtonians rebelled, deriding Harding’s policy as “rag time.” After one summer of anarchy, he backed down. It wasn’t until World War II that DST was adopted again, with only the governor of Oklahoma holding out. However, it was repealed with victory, and in the decades following remained in use in the United States only by local option, with predictably deranged results: one year, Iowa alone had twenty-three different DST systems. Jump to 1965, and seventy-one of the largest American cities had adopted DST, while fifty-nine had not. Confusion reigned, particularly over transport routes, radio programs, and business hours. The U.S. Naval Observatory dubbed its own country “the world’s worst timekeeper.”

The problem was finally resolved by the Uniform Time Act of 1966, although Indiana, (most of) Arizona, and Hawaii still don’t observe DST. In 1996 the European Union, faced with a puzzle map of time zones, standardized DST, while in the United States, as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, DST was extended to begin on the second Sunday of March instead of in April, and to end on the first Sunday of November. As of today, DST has been adopted by more than one billion people in about seventy countries—slightly less than one-sixth of the world’s population.*

Like Robinson Crusoe notching a stick, or inhabitants of the Gulag scratching a line for every day of their imprisonment, we remain enmeshed in time, unable to leave it alone. As recently as August 2007, Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chávez, announced that, to improve the “metabolism” of his citizens, he had ordered the country’s clocks to be moved forward half an hour “where the human brain is conditioned by sunlight”—reversing an opposite decision made in 1965, but one that aligns Venezuela with Afghanistan, India, Iran, and Myanmar, all of which offset time in half-hour increments from Greenwich reckoning. Gail Collins, writing in The New York Times about Chávez’s diktat, likened it to the scene in Woody Allen’s film Bananas, in which a revolutionary hero becomes president of a South American country and announces that from that day on, “underwear will be worn on the outside.”21 But Newfoundland is also on the half-hour system, defying the rest of Canada, while Nepal is fifteen minutes ahead of India, five hours and forty-five minutes ahead of Greenwich. Saudi Arabia supposedly has its clocks put forward to midnight every day at sunset. As one commentator has quipped, “Keeping one’s watch properly attuned aboard the Riyadh-Rangoon express must be an exhausting experience.”22

Nor has fine-tuning stopped there. A second was at one time defined as 1/31556925.9747 of the solar year. But it is nearly sixty years ago now since the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington in England invented the atomic clock, happily to discover that it was more accurate to base timekeeping on vibrating atoms than on the orbiting of the Earth. “It was slightly embarrassing,” recalls David Rooney, curator of timekeeping at the Royal Observatory. “When clocks diverge, it isn’t good. By the seventies, we needed another fudge factor. So the leap second was introduced, to push together Earth rotation time and atomic vibration time.” Such seconds are not inserted every year: the decision to add or subtract one (so far, it has always been added) is made by the International Earth Rotation Service in Paris. The last insertion was on January 1, 2006; it added an extra pip to the BBC time signal.

Now that measuring precise time is the responsibility of agencies such as the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., the International Earth Rotation Service at the Paris Observatory, and the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures in Sèvres, France, all of which define a second as 9,192,631,770 vibrations of the radiation (at a specified wavelength) emitted by a cesium-133 atom, the Sun has been officially deprived of its long-term role as our timekeeper. This definition of a second—the first to be based not on the Earth’s motion around the Sun, but on the behavior of atoms—was formally endorsed in 1967. But those “leap seconds” periodically have to be added to keep our clocks in sync with the planet’s turnings, because the Earth goes its own way in space heedless of atomic time, ensure that we can never entirely turn our backs on the Sun’s guardianship.

One can go on fiddling almost indefinitely (the old joke runs that even a stopped clock is right twice a day). Back in 1907, Einstein came up with the equivalence principle, which states that gravity is locally indistinguishable from acceleration and diminishes as distance increases from the center of mass, so that time goes faster in, say, Santa Fe, high up in New Mexico, than in Poughkeepsie, down low in New York, by about a millisecond per century. A recent experiment on a westward around-the-world jet flight showed that clocks gained 273 nanoseconds, of which about two-thirds was gravitational.23 Meanwhile, a clock eight feet in diameter has been constructed atop Mount Washington in Nevada, made to last ten thousand years (the period of time in which cesium-ion atomic clocks are said to “lose” a second); and a French clock, made by the engineer and astronomer Passement, exhibits a perpetual calendar showing the date through the year 9999.24 An advertisement lauds “the Ultimate Time-keeper,” a watch based on “complex astronomical algorithms” that provides “local times for sunrise and sunset, moonrise and moonset, lunar phase as well as digital, analog and military time for wherever you are,” in A.M./P.M. or 2400 format. It is programmed for 583 cities worldwide and automatically adjusts for DST. Constructed of titanium or steel with a sapphire crystal, it offers “the broadest interpretation of time that money can buy,” and can be purchased for $895.25

The Swiss watchmaker Swatch has proposed a planetwide Internet Time that would enable users throughout the world to bypass individual zones and rendezvous in the same “real” time. Meanwhile, the scientists who run the atomic clock at Teddington, as well as competitors in the United States and Japan, are at work on an even more accurate machine, known as the “ion-trap” and due to be realized by 2020. Experts say that if it were activated now and were still running at the time predicted for the end of the universe, it might be wrong by half a second, if that—twenty times the accuracy of the current most advanced model.26 In 2006, the United States suggested that world time should be switched entirely to the atomic clock, which would involve the dropping of leap seconds—a notion that had the British Royal Astronomical Society up in arms. Had the proposal been accepted, says David Rooney, it would have been the first time in history that time was not dependent on the rising and setting of the Sun.27

Then there is that famous exchange from Waiting for Godot:

VLADIMIR: That passed the time.

ESTRAGON: It would have passed anyway.

* Quoted in Kevin Jackson, The Book of Hours (London: Duckworth, 2007), pp. 164-65. The modern history of pub opening times in Britain begins with “DORA,” the Defence of the Realm Act, passed during the First World War to reduce hangovers among munitions factory workers.

* Similarly, in The Sound and the Fury, Faulkner has the Harvard student Quentin, desperate to escape civil time, shatter his pocket watch, “because Father said clocks slay time. He said time is dead as long as it is clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life.”11 Others have found the very ticking of a clock a thing of solace: T. E. Lawrence, tied down and viciously lashed by his Turkish captors during the Great War, yet notes, “Somewhere in the place a cheap clock ticked loudly, and it distressed me that their beating was not in its time.”12

* Written before the twenty-four-hour clock had entered popular consciousness, the opening line of Orwell’s 1984—“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen”—was intended to make a British reader, unused to continental measurements, feel uneasy. The standard Italian translation (clocks that strike all twenty-four hours having been commonplace in Italy from as early as the fourteenth century) runs: “Era una bella e fredda mattina d’aprile e gli orologi batterono l’una”—in English, “… were striking one.”

* When the United States bought Alaska in 1867, before standard time was implemented, the Russian Orthodox inhabitants suddenly found themselves having to observe the Sabbath on the American Sunday, which was Monday by Moscow reckoning. They were forced to petition for guidance as to when to celebrate Mass—on the Russian Monday or the American Sunday.

* Cesium clocks measure time by counting the ticktock cycles of atoms of the metallic element cesium, each cycle being the exceptionally fast vibrations of the atoms when exposed to microwaves in a vacuum. The fifty-five electrons of cesium-133 are ideally distributed for this purpose, only the outermost being confined to orbits in stable shells. The reactions to microwaves by the outermost electron (which is hardly disturbed by the others) can be accurately determined. As the microwaves hit, the electron jumps from a lower orbit to a higher one and back again, absorbing and releasing measurable packets of light energy. This corresponds to a time measurement inaccuracy of two nanoseconds per day, or one second in 1.4 million years. The experts make the necessary corrections.17

* When clocks move forward or backward an hour, the body’s clock—its circadian rhythm, which is governed by daylight—takes time to adjust. In a study of fifty-five thousand people, scientists found that on days off from work, subjects tended to sleep on standard, not daylight, time.20