2

Tradition in the Making--The Mishnah and the Talmuds

The Mishnah and the Talmuds

The Mishnah is one of the earliest rabbinic works and as such a very important one. It is primarily a collection of legal traditions attributed to rabbis who lived during the first two centuries C.E. According to tradition, it was edited by Yehudah ha-Nasi (Yehudah the Patriarch) at the beginning of the third century. Although most of the material is halakhic, the Mishnah also includes some non-legal material.

The Mishnah

The word mishnah is derived from the Hebrew root shanah, meaning “to repeat,” and refers to the process of orally repeating traditions in order to memorize them. A rabbinic sage during Mishnaic times was called a tanna (plur. tannaim), which is the Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew shanah, and this term has lent its name to the earliest era of rabbinic Judaism, the tannaitic period. During later times, the rabbis were referred to as amoraim (sing. amora) from the root ’amar (“to say”), and the era known as the amoraic period (ca. 225–550).

The Mishnah does not reveal anything about its origins, and major historical events such as the destruction of the second temple and the Bar Kokhba Revolt are mentioned only in passing. Apart from the political and social consequences of these events, they must have raised theological questions, but the Mishnah is remarkably reticent about these matters. The continued validity of the covenant between God and Israel and the question of whether God had abandoned his people are discussed in post-seventy apocalyptic literature, but do not seem to interest the rabbis of the Mishnah. Instead, they are devoted to discussions of the temple and its cult and debates about detailed halakhic matters that no longer had any bearing on everyday life. It is possible that the rabbis behind the Mishnah were confidently awaiting the restoration of the temple, or believed that because the temple cult had been ordained by God the study of its regulations was now the equivalent of their implementation, but it has also been suggested that the rabbis were attempting to create in their minds an ideal and perfect world to which they could escape from the calamities in the world around them. According to this view, the Mishnah represents an early rabbinic vision of a redeemed world where the temple was restored.[1]

The rabbis saw themselves as the custodians of the Torah, and by studying and observing the commandments they were endeavoring to imitate God. In their view, studying the Torah extended to all areas of life and a devout student would attempt to imitate his teacher even concerning trivial details of everyday life. Rabbinic literature often presents the biblical patriarchs and other important biblical characters as observing the Torah according to its rabbinic interpretation. Even God is portrayed as a rabbi studying the Torah and donning tefillin, the small black cubic boxes containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with biblical verses that are attached to the forehead and arm of observant Jewish men during weekday morning prayers in accordance with Deut 6:8. This is undoubtedly a way of asserting that rabbinic Judaism was the legitimate heir and continuation of biblical tradition, but it may also suggest that this form of Judaism was the ideal one in the eyes of the rabbis.[2]

Structure and Content

Basically, the Mishnah is organized topically and contains six major orders or divisions (sedarim, sing. seder), which in turn are divided into sixty-three tractates (massekhtot, sing. massekhet). These tractates are then divided into chapters (peraqim, sing. pereq) and mishnayot (sing. mishnah), the mishnah being the smallest unit.

Zeraim (seeds) mainly contains laws pertaining to agriculture but this order also includes the tractate Berakhot (benedictions) that deals with regulations for prayer.

Moed (appointed times or Festival Days) contains laws concerning the Sabbath and festivals. Tractate Pesahim, for example, includes regulations for the celebration of Passover, and tractate Sukkah instructions for how to build a sukkah (booth).

Nashim (women) mainly contains laws concerning marriage, marriage contracts and divorce, as well as vows and their cancellation.

Nezikin (damages or civil law) includes, among other things, laws covering damages and torts, laws regulating conduct of business, labor and real estate transactions, and criminal penalties.

Qodashim (holy things) mainly contains laws of sacrifices in the temple.

Toharot (purities) contains laws of ritual purity, or rather laws defining the way people and things contract or eliminate ritual impurity.[3]

The Mishnah is characterized by a terse style, which seems to assume that the reader is familiar with the topics discussed. No background information is offered and one gets the impression of being thrown into the middle of a discussion between well-informed people who communicate by means of key words. Most likely, the Mishnah was not aimed at ordinary people but rather compiled by rabbis for rabbis and their students. The debates take the form of detailed concrete examples and only rarely are general rules formulated. It can hardly have been easily accessible even in its own time, and for modern people who do not share the worldview and basic assumptions of rabbinic Judaism, it is even more difficult to understand. An example from tractate Berakhot will illustrate some of these characteristics:

From what time do we recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the priests enter [their homes] to eat their heave-offering, until the end of the first watch. This is the view of R. Eliezer, but the rabbis say, “Until midnight.” Rabban Gamaliel says, “Until the rise of dawn.” It happened once that his sons returned from a banquet and said to him: “We have not yet recited the Shema.” He told them: “If it is not yet dawn you should recite it.” And not only in this case but in all cases where the rabbis say “until midnight,” the obligation persists until the rise of dawn . . . If so, why did the rabbis say “until midnight”? In order to keep humans away from transgression.

From what time do we recite the Shema in the morning? From the hour that one can distinguish between blue and white. R. Eliezer says, “Between blue and green.” And one must complete it before sunrise. R. Yehoshua says, “By the third hour, because it is the habit of royalty to rise by the third hour.” One who recites later has not lost [anything], for he is as one who reads from the Torah.[4]

One need not understand all the technical details of the text to see that it takes a lot for granted. The reader is expected to know what “reciting the Shema” means, agree that it is to be read twice a day, and be familiar with terms such as “heave-offering” and “first watch.” No effort is made to explain the meaning of these concepts and terms. Another typical feature of the Mishnah is that disagreements are not resolved. Different opinions stand side by side and there is no hint as to which one should be followed. The Mishnah is the earliest canonical text that preserves tradition in the form of disputes. Moreover, the various opinions in the Mishnah are usually stated without reference to Scripture, and although occasional quotations from the Bible do occur, the Mishnah generally appears to take its own authority for granted.[5]

During the tannaitic, period there seems to have been two ways of organizing halakhah; thematically as in the Mishnah, or according to biblical verses as in the collections of midrash. The relationship between these two modes has been the subject of a long-standing scholarly debate in which some scholars maintain that the method of deriving laws from Scripture (midrash) is the older, while others hold that the earliest oral tradition developed independently of the Bible (Mishnah) and was only later buttressed through a connection to a biblical verse. Those who believe the midrash method to be the older claim that Scripture was an integral part of the process of shaping new laws and that many legal decisions are derived through the interpretation of a biblical verse. Yet other scholars maintain that the two methods existed side by side and whereas some laws really seem to be the result of interpretation of a verse, others appear to have been created independently of Scripture and only later corroborated by linking them to a biblical verse.[6]

Purpose and Redaction

As mentioned above, the Mishnah was redacted in the early third century but it also contains earlier traditions. Rabbinic tradition unanimously regards Rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi, also known simply as Rabbi, as the redactor of the Mishnah, and while it is clear that numerous additions were made after his time, scholars agree that as long as we suppose that for a time the text retained a certain flexibility, Rabbi can be seen as the main figure under whose authority the Mishnah was edited. The Mishnah contains traditions from different time periods, and purportedly some even go as far back as the Second Temple period, but scholarly opinion differs as to the extent of later reworking of these traditions. A much-debated issue is whether it is at all possible to reconstruct earlier periods based on these traditions, or whether they have been reworked so much that they rather reflect the time of their redaction.

Traditionally, traditions from four different periods have been discerned in the Mishnah:

The Second Temple period

The Yavneh period (ca. 70–135)

The Usha period (135–170)

The time of the final redaction (ca. 225)

Although attributions to individual rabbis cannot be taken at face value, most scholars agree that traditions can be assigned with reasonable confidence to a particular time period. In addition to views attributed to named rabbis, the Mishnah also contains anonymous opinions, traditionally considered to reflect the view of the redactor. However, in many cases these anonymous teachings do not correspond to the opinion of Rabbi as attested elsewhere. While it is possible that Rabbi changed his opinion, or chose to include teachings with which he did not agree in order to make the Mishnah acceptable to as many as possible, it may also be the case that the Mishnah was simply not consistently redacted in accordance with Rabbi’s views. Many rabbinic texts have undergone this kind of redaction where the redactor in some cases has reworked the sources in accordance with his view but in others preserved earlier traditions intact even if they did not conform to his opinion.

Another issue that is subject to scholarly debate is the purpose of the Mishnah. Is it to be understood as an authoritative law code, an anthology of legal sources, or a legal teaching manual? This question has important implications for how the Mishnah should be understood and employed for the history of Judaism, both rabbinic and pre-rabbinic. Since it mainly includes legal sources, it seemed natural to assume that it was intended to be a law code. But it has been argued that the many repetitions and contradictions—as well as the fact that it often fails to make clear which one of the many cited opinions is valid halakhah—undermines this view. In addition, the view of the Mishnah as a legal code leaves unexplained the parts that legislate practices or presume institutions that were no longer functioning after the destruction of the temple. The view of the Mishnah as a guide for teaching is a mediating position according to which the redactor made a selection of available material but also chose to include traditions with which he himself did not agree in the attempt to create a universally acceptable summary of halakhah.[7]

Recently a modification of this view has been suggested according to which the function of the Mishnah was indeed pedagogical, but, rather than conveying halakhic norms as the traditional view would have it, its purpose was to impart to its students a way of thinking. The cases preserved in the Mishnah were meant to develop the intellectual skills of the students and teach them to apply the norms of the legal system. The Mishnah’s function, then, was primarily pedagogical but since it also conveys information about the standards and norms of the legal system it may also have served as an authoritative source of normative law.[8]

If the primary aim of the Mishnah was to train students in various modes of legal analysis, it would explain its disproportionate interest in improbable cases and circumstances as well as borderline cases. Situations that involve a pigeon found exactly half-way between two domains (m. B. Batra 2:6) or the man who tithes doubtfully-tithed-produce while naked (m. Dem. 1:4) were not likely to occur but would be of interest to the Mishnah because the disparate circumstances involved in each invoke or allude to a different legal principle. By creating such scenarios, the Mishnah could bring competing principles into conflict, thereby compelling the student or audience to consider how diverse and competing legal concerns interact with one another. In a similar way, the ambiguities inherent in borderline cases would encourage students and listeners to reflect on how to apply appropriate legal principles, promoting sophisticated analytic thinking.[9]

The extent to which the Mishnah underwent an intentional redaction is a much-debated question. Most scholars would agree that the Mishnah displays structuring principles and creates coherence and meaning through various linguistic patterns and literary devices such as repetitions, inclusios (words, themes, or sounds from the beginning of a literary unit that are repeated, with some alteration, at the end of the unit), and enchainments (the linking of one mishnah to the next by means of a repeated phrase or word). A number of recent studies focusing on these features and techniques argue that they are not random, natural recurrences of language nor features introduced to ease memorization but rather the intentional product of a redactor who was responsible for selecting and imposing coherence on the material. These literary devices employed by the redactor may be understood not only to provide coherence and unity but also to convey ethical and theological meanings.[10]

Oral Transmission

The Mishnah is very much associated with orality and its succinct style and mnemonic features are commonly taken as evidence of oral recitation and transmission. According to traditional accounts, oral transmission of mishnaic traditions were formulated with great precision and consisted of a fixed verbal content that was transmitted primarily through rote memorization. The Mishnah was even considered to have undergone an oral publication process before it was finally written down.[11] The assumption underlying the traditional view is that the orally transmitted text looked very much like the text as it was later written down and while written notes may have existed, only the oral version of the Mishnah would have been authoritative.[12]

However, recent scholarship on oral transmission in diverse cultures has shown that oral transmission does not necessarily start with a fixed text and that oral performance does not automatically aim for word for word reproduction. Rather, texts in oral settings tend to be fluid and the transmission process an active one where the performer does not passively transmit traditions verbatim but rather interprets and shapes them. This insight has influenced the view of the development of the Mishnah and has led some scholars to view the mishnaic material as compositional building blocks from which traditions could be constructed in various ways in different performative settings rather than an orally transmitted fixed text.[13]

It is also increasingly recognized that oral transmission and literary composition coexist and interact in a variety of ways. A written text can interact with oral performance even after it is written down and is not necessarily fixed. It is not only a record of past performative events but can also serve as a script for future performative events. Rather than seeing oral traces in the mishnaic text as an aid to rote memorization, they can be understood as a script for an oral performative event. The transmission process may have consisted of different phases where the earlier ones were characterized by a large degree of fluidity while the later ones more closely resembled the model of oral recitation as rote memorization.

Also, rather than implying an exclusively oral transmission, the notion of Oral Torah, of which the Mishnah formed a part, may have been designed to distinguish the part of revelation that was given orally at Mount Sinai from the one given in writing. To retain both the oral and the written components of the Torah and distinguish between the two may have been a way of reenacting the original revelation and preserving not only the content of revelation but also the mode.[14]

Even though the Mishnah was not originally considered a binding law code, later generations regarded it as such. This view of the Mishnah as an authoritative text led to attempts at harmonizing contradictory views and to reinterpretations in order to make the Mishnah agree with contemporary understandings of halakhah. The rabbis of the post-mishnaic period also devoted themselves to clarifying passages that seemed obscure, expanding the discussions, and extracting general principles of action from the particular rules of the Mishnah, and thus the commentaries grew. The first generation discussed the Mishnah, the second generation continued this discussion while also adding comments on sayings by their predecessors, the third generation added comments on both sets of earlier commentaries as well as discussions on their relationship to one another, and thus the Talmuds took form.

The Tosefta

Before presenting the Talmuds, however, mention should be made of the Tosefta, another rabbinic compilation whose main content originates from approximately the same time as the Mishnah. The Aramaic word tosefta means “addition” and until recently there was a scholarly consensus that the Tosefta was an addition to, or continuation of, the Mishnah. In recent years, however, scholars have noted that the relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta seems to be more complex and a number of different theories have been suggested.

The structure of the Tosefta is identical to that of the Mishnah, its language is mishnaic Hebrew, and the rabbis mentioned in the Mishnah are also found in the Tosefta. The Tosefta also covers the same topics but it is approximately three times the size of the Mishnah. Where the Mishnah only cites a few different opinions, the Tosefta often develops the subject more extensively and includes more rabbinic opinions. Sometimes it also formulates rules that significantly differ from those found in the Mishnah concerning the same subject. In addition to the material that the two works have in common, the Tosefta also contains traditions from rabbis that lived a generation or several generations after the latest ones cited in the Mishnah.[15]

Close comparisons between the Mishnah and the Tosefta have given rise to contradictory theories concerning their relationship. While some Tosefta passages give the impression of being a commentary and a continuation of the Mishnah, others seem to predate their parallel version in the Mishnah. This has led some scholars to suggest that some Tosefta passages may actually predate their mishnaic parallels even if the redacted form of the Tosefta postdates the Mishnah. Others have proposed that the relationship varies from tractate to tractate, so that some tractates of the Mishnah are earlier than their counterparts in the Tosefta while others are later.[16]

Recently, it was suggested that the Tosefta is a commentary on an earlier version of the Mishnah, a kind of “Ur-Mishnah.” Both this Ur-Mishnah and the Tosefta served as sources for our present Mishnah, which means that the Tosefta may in some instances be the source of the Mishnah, while in others a commentary on it. The Ur-Mishnah was sometimes incorporated into our present Mishnah without being reworked, and in these cases, the Tosefta looks like a commentary to the Mishnah. According to this view, the fact that the Tosefta cites rabbis from a later time than the Mishnah—often cited as evidence that the final redaction of the Tosefta took place later than that of the Mishnah—means only that the redactor of the Mishnah in certain cases chose not to include these later traditions. Either they were not considered as authoritative as the earlier traditions, or they were, in some cases, incorporated without attributing them to named rabbis.[17]

The Talmuds

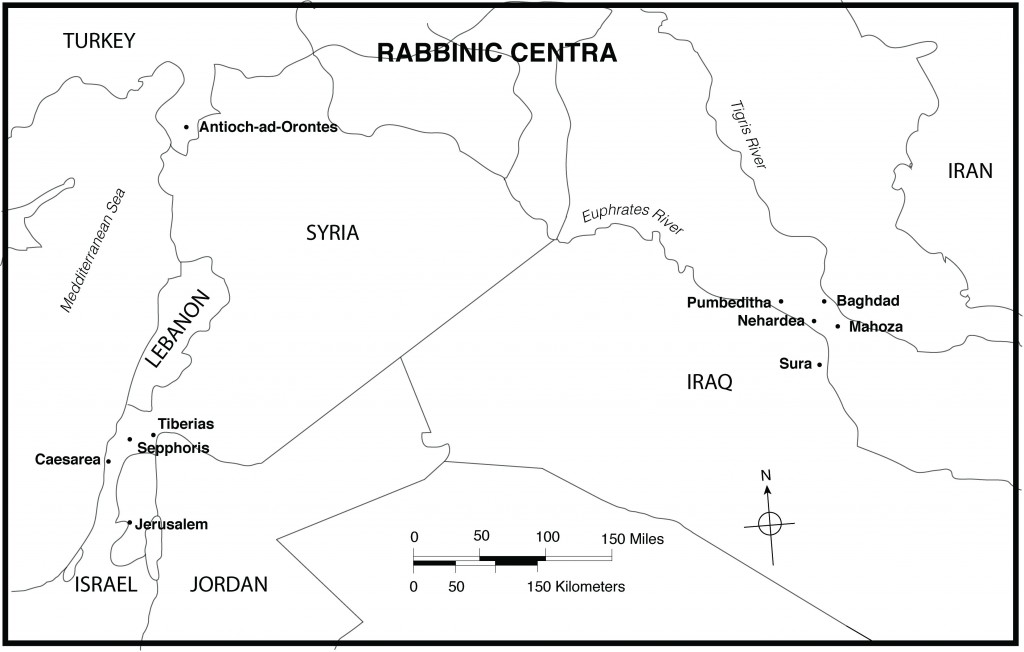

During the amoraic period, two other rabbinic compilations emerged: the Palestinian or Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi), whose final redaction took place in the land of Israel circa 400 C.E., and the Babylonian Talmud (Bavli), composed by rabbis who lived in Babylonia from the third through the seventh or eighth century. The word “Talmud” is derived from the Hebrew verb lamad, which means “to study.” Alongside the Bible, the Babylonian Talmud is the most important Jewish text, and it has exerted a tremendous influence on Jewish tradition from late antiquity until the present.

The two Talmuds emerged in very different cultural contexts: the Palestinian Talmud in the land of Israel, which was under Roman rule and influenced by Greco-Roman culture, and the Babylonian Talmud in the Sassanian Persian Empire, a religiously diverse region populated by Zoroastrians and Christians of various stripes. Under the Sassanians, the Jews enjoyed limited self-rule and were represented by the exilarch, the Babylonian counterpart to the patriarch.

In spite of their development in different milieus, the Palestinian and the Babylonian Talmud exhibit many basic similarities. They are both continuations of the debates in the Mishnah and share much of their content. There seems to have been close contacts between the rabbinic centers in the land of Israel and Babylonia, and the rabbis often traveled back and forth sharing learning and exchanging traditions. The Babylonian Talmud, however, continued to develop a few centuries after the redaction of the Palestinian Talmud and is therefore much more extensive. It has certain unique traits, which can be explained by cultural conditions specific to Babylonia and the fact that it in part reflects a later time period.

During the amoraic period, the Jewish center slowly moved from the land of Israel to Babylonia, where the rabbinic community gained in importance and self-esteem, emerging as a rival to the one in the land of Israel. A veritable competition developed between these two rabbinic centers, in which the Babylonian rabbinic community claimed to be the equal of the one in the land of Israel and according to some, even superior to it: “We consider ourselves in Babylonia as being in the land of Israel, from the day Rav came to Babylonia.”[18] Redefining “Zion” as the rabbinic academy rather than a geographical place, the Babylonian rabbis were able to reinterpret biblical references to Jerusalem as referring to Torah learning in Babylonia, even to the point of strongly dissuading emigration to the land of Israel.[19] In response, the Palestinian rabbis began emphasizing the importance of living in the land of Israel, even asserting that this was the equivalent to fulfilling all the commandments in the Torah.[20] With the shift of center to Babylonia, the Babylonian Talmud gained influence at the expense of the Yerushalmi. From the eighth century onward, it almost completely replaced the Palestinian Talmud, and the Mishnah was practically studied only through the Babylonian Talmud.

In addition to the halakhic material from the Mishnah, the Talmuds—the Babylonian one in particular—contain large amounts of aggadic material such as legends, folk tales, scriptural interpretations, magical incantations, and observations about theology, medicine, astronomy, and medicine. As much as a third of the Babylonian Talmud consists of aggadah, parts of which consists of commentary on Scripture. The Jerusalem Talmud is more narrowly focused on law and Mishnah commentary, which is likely due, at least in part, to the fact that in the land of Israel scriptural interpretations were compiled in special collections that circulated independently (midrash). Both Talmuds develop and expand the debates in the Mishnah, but they also contain a large amount of additional material that is only loosely, or not at all, connected to the Mishnah. They both developed during a very long time and therefore contain material from different time periods. In addition to the text of the Mishnah itself, they also include material from the tannaitic period that was not included in the Mishnah, known as baraitot (sing. baraita), as well as traditions from the amoraic and post-amoraic periods.

The Babylonian Talmud

The content of a tractate in the Babylonian Talmud is organized loosely around a specific topic, creating a literary unit known as sugya (pl. sugyot) in Hebrew. A sugya is typically comprised of traditions from different time periods, with the oldest material dating from the tannaitic period and the latest from the post-amoraic period. Sayings from the post-amoraic period are unattributed and transmitted anonymously (stam in Hebrew), giving no hint as to their date. Traditions from the tannaitic period are transmitted in Hebrew, the amoraic sayings appear in a mixture of Aramaic and Hebrew, and the anonymous layer is almost entirely in Aramaic.

The unattributed sayings are characterized by a certain terminology as well as specific literary features and usually provide an interpretive framework for tannaitic and amoraic sayings, only rarely making independent assertions of their own. It is for this reason that the anonymous layer is commonly considered later than the others, even if shorter anonymous additions may have originated already in the amoraic period.[21] The anonymous layer is quite thin in the Palestinian Talmud, but makes up as much as fifty percent of the Babylonian Talmud.

Below is the Babylonian Talmud’s expansion of the mishnaic passage at the beginning of tractate Berakhot. The citations from the Mishnah appear in capital letters and the citations from the Bible in italics:

On what does the Tanna base himself when he says: FROM WHAT TIME [IS THE SHEMA RECITED]? Furthermore, why does he deal first with the evening [Shema]? Let him begin with the morning [Shema]! The tannaitic rabbi bases himself on Scripture, where it is written [Recite them . . .] when you lie down and when you get up [Deut. 6:7] and he teaches thus: When does the time of the recital of the Shema of lying down begin? When the priests enter to eat their terumah [heave-offering]. And if you like, I can answer: He learns [the precedence of the evening] from the account of the creation of the world, where it is written, And there was evening and there was morning, a first day [Gen. 1:15] . . . FROM THE TIME THAT THE PRIESTS ENTER TO EAT THEIR TERUMAH. When do the priests eat terumah? From the time of the appearance of the stars.[22]

Without going into all the technical details, several observations concerning the Talmudic commentary (gemara) can be made on the basis of this brief passage. While the Mishnah merely states that one should recite the Shema, the gemara fills in background details perceived to be missing, such as the reason why the Shema should be recited at all and why the recitation of the Shema in the evening is mentioned before the recitation of the Shema in the morning. One might think it more logical to begin with the recitation of the morning Shema, so why does the Mishnah begin with the evening? After asking these questions, the gemara answers them by providing prooftexts from the Bible. The rabbi in the Mishnah bases his teaching on Deut. 6:7, where the recitation of the Shema is prescribed, and the reason for mentioning the evening Shema first is that it appears in this order in the biblical verse: “when you lie down” is mentioned before “when you rise.” The gemara then provides additional support for mentioning the evening Shema first, citing Gen. 1:5 in which evening precedes morning.

The structure of a traditional page from the Babylonian Talmud was established at the time of its first printing in 1520–1523. Subsequently, more commentaries were added, but the appearance of the page has changed very little. The edition that served as the model for all later editions is the Vilna edition, printed in 1880–1886. The next pages depict a traditional page of the Babylonian Talmud together with an explanation of the most important commentaries appearing on the page.[23]

Fig. 4. Page of the Babylonian Talmud, Vilna Edition (tractate Taanit 10a). Photograph by the Royal Library, Copenhagen. Used by permission.

The Layout of a Talmud Page

- The number of the page in Hebrew letters. Every sheet (double page) is numbered and the first side of the sheet is called a, and the second side is called b. The standard practice when referring to a page of the Talmud is to cite the name of the tractate, the number of the sheet, and the side, for instance, Taanit 10a. To indicate which Talmud is meant, the letters y (Yerushalmi) or b (Bavli) is placed before the tractate, for instance, b. Taanit 10a.

- The name of the tractate.

- The main text on a Talmud page, consisting of the Mishnah and gemara.

- Abbreviation of the word matnitin, indicating the beginning of a quotation from the Mishnah.

- Abbreviation of the word gemara, indicating the beginning of the amoraic commentaries on the Mishnah.

- Commentary by Rashi (R. Shlomo Yitzhak 1040–1104), found on the inner side of the page closest to the binding in all traditional editions of the Talmud. Rashi lived in Troyes, France, and his explanations are the most famous and widely read commentary to the Talmud. He explains the text, sometimes translating into French (and occasionally German), words or expressions that were no longer familiar to people of his time. In order to separate it from the main text, Rashi’s commentary appears in “Rashi-script,” a script that is slightly different from the regular Hebrew characters.

- Tosafot (literally “additions”), appear in the outer column of the page (also in Rashi-script). They began as additions to Rashi’s commentary by his disciples and descendants, but developed into an independent interpretation of the gemara.

- Commentary by Rabbenu Hananel (990–1055), one of the earliest commentaries on the Talmud.

- Ein mishpat ner mitzvah. References to the main law codes dealing with the same topic as the gemara. The law codes most commonly referred to are Mishneh Torah by Maimonides (1138–1204), Sefer Mitzvot Gadol by Rabbi Moses of Coucy (first half of the thirteenth century), Arba‘ah Turim by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher (ca. 1270–1340), and Shulhan Arukh by Rabbi Joseph Caro (1488–1575).

- References to biblical passages.

- Masoret ha-Shas. Cross-references to parallel passages elsewhere in the Talmud.

- Haggahot ha-Bah. Proposed emendations in the text of the gemara, Rashi’s commentary, and the Tosafot, by Rabbi Yoel Sirkes (seventeenth century).[24]

The Anonymous Layer

As mentioned above, much of the Babylonian Talmud consists of anonymous discussion characterized by a discursive style. While amoraic sayings are often brief, stating viewpoints without explaining the reasoning behind them, the anonymous layer explores the logic, reasons, and consequences underlying these statements, producing long dialectical debates in which various opinions and possibilities are compared, analyzed, and explained, with equal attention to minority opinions, which have no bearing on practical law. In contrast to the rabbis from an earlier period who seem to have considered analysis and argumentation as merely a means to reach a conclusion and not worthy of preservation, the rabbis behind the anonymous layer seem to have valued analysis and argumentation as ends in and of themselves. Sometimes it seems that they even created debates by juxtaposing statements that originally had no connection to each other, presenting them in question and answer form.[25]

It has been suggested that the willingness to engage in argumentation and the interest in preserving different, sometimes contradictory viewpoints and pursuing their underlying rationales and consequences reflects a recognition that a single undisputed divine truth is unobtainable. The rabbis maintained that after the cessation of prophecy, the only way to seek out God’s will was through interpretation of the Torah, an activity that gives humans a crucial role in establishing God’s will. However, humans are, by definition, imperfect, and therefore human interpretation will also be imperfect and incomplete. Being dependent on human interpretation, the divine message is available only in a multiplicity of human interpretations. Because any single interpretation encompasses only part of the truth, preserving many alternate interpretations becomes a way of grasping as many aspects of the divine truth as possible. Accordingly, a minority view is no less a reflection of an aspect of God’s will than the majority opinion.[26]

The reason why the rabbis behind the latest Talmudic layer chose to be anonymous is the subject of scholarly debate. A common view is that they did so in order to distinguish their additions, which they considered less authoritative, from the teachings of the amoraim. Presumably, they regarded their work as a restatement and clarification of what to earlier generations was self-evident, and believed that they were adding nothing new. According to this view, transmitting their comments anonymously was a way of acknowledging the supremacy of earlier generations.[27]

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Layers in the Talmud

Anonymous/Redactional layer

Dialectical discussions of the

tannaitic and amoraic material

Amoraic layer

comments on mishnayot and baraitot

Tannaitic layer

mishnayot

baraitot

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Redaction

In the view of David Weiss Halivni, the father of source-critical analysis of the Talmud, it is these anonymous commentators who were responsible for the redaction of the Babylonian Talmud during a period ranging from the middle of the sixth century to the middle of the eighth.[28] These redactors arranged, interpreted, and discussed the material, weaving together amoraic sayings with baraitot, as well as adding their own comments. In Halivni’s opinion, the sugya is essentially the creation of the redactors.[29] Other scholars are reluctant to assign redactional activity to a specific time period and have suggested that the features typical of the anonymous layer are characteristics of redactional activity rather than traits typical of a distinct historical era.[30]

Recently, Judith Hauptman has proposed a modification of Halivni’s model, arguing that the sugya developed gradually in chronological order. According to her theory, the baraitot commenting on the mishnah constitute the oldest redacted stratum of the sugya, to which rabbis from the amoraic period added their comments. Finally, the redactors added their comments and interpretations, tying everything together and providing an interpretive framework.[31]

In recent years Jeffrey Rubenstein, a student of Halivni’s, has argued that the redactors of the Talmud also authored or reworked many of the Bavli’s lengthy and complex stories. Developing an approach to the study of Talmudic stories that combines literary analysis with source and form criticism, he maintains that a close study of Bavli narratives reveals that they were composed by means of creative reworking of earlier sources with methods and techniques of composition akin to those exhibited in legal sugyot, as described by Halivni and others. This similarity in methods and technique, together with the fact that many of the complex stories express admiration for skill in dialectic argumentation, an activity highly valued by the redactors of the legal material, led him to conclude that the redactors were responsible not only for the structure of the legal material but also for the stories. Since many typically Babylonian motifs and concerns, common in Bavli stories but absent from their Palestinian parallels, appear primarily in narratives that exhibit redactional techniques of composition, he argues that these specific Babylonian motifs should be attributed to the redactors rather than to the rabbis from the amoraic period. If he is correct, the lengthy and complex stories may be dated as late as the sixth and seventh centuries rather than to the third and fourth.

The idea of the redactors as the main authors of the Bavli stories has been challenged by other scholars who either maintain that the contribution of the redactors cannot be clearly separated from that of the amoraim, or believe that the stories should be attributed mainly to the amoraim. In any event, whether or not Rubenstein’s theory of the redactors as authors of the stories is embraced, there is general agreement that his studies demonstrate important differences between Palestinian and Babylonian rabbinic culture and have greatly enhanced our understanding of both the stories and culture of the Babylonian Talmud.

In Babylonia, Torah study was esteemed as the highest value, even at the expense of other parts of religious life, and based on a number of stories in the Babylonian Talmud, Rubenstein argues that rabbinic culture in the post-amoraic period was elitist, with rabbinic interests revolving around matters connected to the academy, such as legitimate leadership and the proper way of conducting debates. In his view, many specifically Babylonian rabbinic concerns can be explained against the background of the large academies that had developed in Babylonia with a strict hierarchy and a competitive, even hostile atmosphere.

Students sat in rows according to their status, the best students in the front, and the more inferior ones in the back. At the top of the hierarchy was the head of the academy who was appointed based on proficiency in Torah and eminent ancestry, the latter a significant concern in Sassanian culture. In this milieu, a particular rabbi’s place in the academic hierarchy was largely dependent on his ability to excel in argumentation. Failure in this regard would lead to demotion and humiliation, and accordingly, dialectical ability came to be considered the most exalted and valued form of learning. Success in the academy was a delicate business that depended on a rabbi’s ability to defeat his opponents with clever arguments while at the same time taking care to avoid insulting or embarrassing his colleagues.[32]

Because these large rabbinic academies were located in the cities, students had to spend extended periods of time away from their homes and families, creating a tension between marriage and study, and between studying and earning a living. Such tensions underlie a number of Bavli stories, and may explain the view of wives as an obstacle to Torah study that appears in some stories.[33]

Another scholarly debate concerns the extent to which the redactors have reworked their sources, a question that has ramifications for the possibility of using the Talmud as a source for historical reconstruction. If the Talmud preserves sources from the different time periods of its development, transmitted without too much interference from the redactors, it can be used as a historical source for the period prior to its final redaction, but if the redactors have altered them beyond recognition in adapting them to the concerns and values of a later period, it can only be used as a historical source for the time of its redaction.

Jacob Neusner is the primary proponent of the latter view, claiming that the Talmud is basically a creation of its final redactors. While acknowledging that the Talmud contains sources from earlier periods, he maintains that they have been reworked beyond recognition by the final redactors.[34] A majority of scholars, however, believe that it is possible to distinguish different layers from different time periods based on grammar, terminology, and style. While acknowledging that earlier sources are reflected through the concerns and values of the redactors’ time, they maintain that they are neither thoroughly nor consistently reworked. The freedom of reworking seems to vary and in general the redactors seem to have been more restrained with regard to halakhic material than with aggadah.

These scholars point out that the Babylonian Talmud itself calls attention to its various sources by citing traditions in the names of different rabbis, by the use of different citations formulae, and by the alternation between Hebrew and Aramaic. Even if it cannot be ascertained that a saying attributed to R. Aqiva really goes back to him, most scholars maintain that it is possible to draw some general distinctions between Babylonian and Palestinian rabbis, and between tannaim and amoraim. It is true that the sophisticated literary character of stories in the Talmud diminishes their value as sources for historical events, but although they do not always yield information about historical facts, they nevertheless reflect rabbinic values and attitudes. Most scholars agree that cultural-historical information can be obtained from rabbinic texts provided they are read critically. Such a critical reading involves recognition of the important roles of the redactors in transforming earlier sources, as well as attention to the special literary characteristics of the text,[35] a topic to which we will return shortly

The Palestinian Talmud

The Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud Yerushalmi (Jerusalem Talmud), is the commentary on the Mishnah produced by the rabbinic community in the land of Israel during the third and fourth centuries. In spite of its name, it was not produced in Jerusalem but in various locations in the Galilee. A sugya in the Palestinian Talmud is generally simpler than a Bavli sugya and typically consists of tannaitic material, briefly commented upon. Only occasionally do longer dialectic debates occur.

The development and redaction of the Palestinian Talmud have drawn much less scholarly attention than studies of the Babylonian Talmud and many conclusions are yet tentative. The Palestinian Talmud seems to have developed through accumulation of additional layers of commentaries with the passing of time without much redactional intervention. The fact that similar terminology and modes of reasoning are used throughout the whole work, and the same rabbis quoted in all of its parts, suggests that it underwent a single uniform redaction. Most scholars assume that the final redaction was minimal and simply the last stage of the accumulation of traditions. In contrast to the anonymous material in the Babylonian Talmud, the Yerushalmi’s anonymous material does not differ substantially from the attributed traditions. Accordingly, it has been argued that there is no compelling reason to attribute this material to later redactors, or for assuming that they played a significant role in the formation of the Palestinian Talmud.[36]

The relationship between the two Talmuds is a matter of scholarly debate. On one hand, they share much of their content, but on the other, they are also very different. The similarities have commonly been explained by the extensive exchange of material that took place when the rabbis travelled back and forth between the land of Israel and Babylonia and brought their respective traditions along, but until recently there was a relative consensus that the redactors of the Babylonian Talmud did not know the redacted form of the Palestinian Talmud. While they may have had access to an early version of the Yerushalmi, which both they and the redactors of the Palestinian Talmud may have used as a base for their respective compilations, most scholars believed that the redacted form of the Yerushalmi was unknown to them.

However, a recent study of tractate Avodah Zarah has demonstrated that there are significant structural similarities between the two Talmuds in this particular tractate, raising the possibility that the Babylonian redactors did in fact know a Yerushalmi version that closely resembles the present one. The author argues that the similarities are so striking that they can hardly be explained by a common source of traditions, but rather seem to be a result of a Babylonian revision of a completed Palestinian version.[37] This raises the possibility that the Babylonian redactors had access to a redacted version of the Jerusalem Talmud for other tractates also, although this has yet to be demonstrated.

The differences between the Palestinian and the Babylonian Talmuds are likely the result of both cultural and chronological factors. While the Palestinian Talmud was redacted around 400 C.E., the Babylonian Talmud continued to develop for several hundred years. Scholars differ over whether the differences should be attributed primarily to the rabbis of the amoraic period, or whether they are the outcome of later reworking by the Babylonian redactors.

Rabbinic Literature as a Source for Historical Reconstruction

As mentioned above, most scholars maintain that rabbinic sources can be used to obtain some historical information, although the view of the kind of data they are believed to yield has changed considerably during the last fifty years. A general skepticism to rabbinic traditions, an awareness of the role of redactors in reworking earlier material, and the recognition that rabbinic narratives are literary artifacts have thoroughly changed the prospect of using rabbinic literature as a source for historical reconstruction.

At the beginning of the academic study of Judaism in the nineteenth century, scholars treated rabbinic literature as a relatively reliable source of historical information. It was presumed that rabbinic stories conveyed something that actually had happened and that they reflected a historical reality. Although scholars recognized their exaggerated and legendary elements, they believed that it was possible to get behind the text and isolate a “historical kernel” through critical analysis. By excluding the supernatural elements and harmonizing different sources, detailed reconstructions of rabbinic history and biographies of individual rabbis were produced.

Jacob Neusner vehemently criticized this approach starting in the early 1970s. He demonstrated that many traditions in different rabbinic compilations, and sometimes even within the same compilation, contradict each other and that later texts often rework earlier ones so that there is no way to distinguish historical descriptions from fiction. While earlier scholarship tended to consider all divergent versions of an event as essentially reliable, Neusner showed that later versions were often not independent historical testimonies but rather the result of transformations of earlier sources in the course of transmission, or deliberate reworkings of an earlier source. He also questioned the accuracy of attributions of sayings to individual rabbis and promoted a generally skeptical attitude toward historical accuracy of traditions in general, since they are often recorded long after the events they purport to describe.[38]

With Neusner, scholarly focus essentially shifted from the historical context of the characters within a story to that of the storytellers behind the story. A certain skepticism to rabbinic traditions in general is now prevalent among most scholars. For instance, traditions attributed to early Palestinian rabbis that appear only in the Babylonian Talmud are no longer automatically considered to convey accurate information about the conditions in the land of Israel at the time when these rabbis lived. Rather, most scholars at least consider the possibility that these traditions reflect later Babylonian conditions that have been projected back to earlier centuries. The same applies to purportedly tannaitic traditions in the Babylonian Talmud that lack parallels in tannaitic compilations. Although it is possible that they indeed date from tannaitic times but happen to be preserved only in the Bavli, one must consider the possibility that they originated with amoraic or post-amoraic rabbis.

The recognition that rabbinic stories are literary creations told for didactic purposes and not intended to record historical events has significant ramifications for the view of their potential to reveal historical facts. Rather than trying to get behind the stories to a historical reality, scholars have turned their attention to the message of the story and developed methods to determine the meaning of the extant text. An important proponent of a literary approach to rabbinic stories is Jonah Fraenkel, who developed a method of close reading of narratives with careful attention to wording, structure, and plot. He rejects all approaches that consider rabbinic stories as historical sources, arguing that to treat them as such is a misunderstanding of their genre. Rabbinic stories are fiction, he maintains—reflecting the spiritual world of the storytellers, not the real world of the characters—whose meaning emerges through a close reading that identifies the structure, determines the plot, describes the characters, and analyzes literary devices.[39]

However, even narratives that are made up and told for didactic purposes reveal something about their authors’ values and concerns, and although they may not yield much information about specific historical events or details of individual rabbis’ lives, they may provide a window to rabbinic attitudes and ideas. Provided they are read critically, taking into account their sophisticated literary character, rhetorical features, and the role of the redactors in transforming the sources, most scholars agree that rabbinic sources can be used for reconstructions of the history of rabbinic ideas and attitudes.[40]

The well-known story of the deposition of Rabban Gamliel in b. Ber. 27b–28a may serve to illustrate which kind of information can be derived from rabbinic sources:

Our sages have taught [in a baraita]: Once a certain disciple came before R. Yehoshua. He said to him: “The evening prayer—optional or obligatory?” He said to him: “Optional.” He came before Rabban Gamliel. He said to him: “The evening prayer—optional or obligatory?” He said to him: “Obligatory.” He said to him: “But did not R. Yehoshua say to me ‘optional’?” He said to him: “Wait until the shield-bearers [the sages] enter the academy.”

When the shield-bearers entered,[41] the questioner stood up and asked: “The evening prayer—optional or obligatory?” Rabban Gamliel said to him: “Oligatory.” Rabban Gamliel said to the sages: “Is there anyone who disagrees on this matter?” R. Yehoshua said to him: “No.” Rabban Gamliel said to him: “But did they not say to me in your name, ‘Optional’?” He said to him: “Yehoshua! Stand on your feet that they may bear witness against you.”

R. Yehoshua stood on his feet and said: “If I were alive and he [the student] dead—the living could contradict the dead. Now that I am alive and he is alive—how can the living contradict the living?” [that is, how can I deny that I said this?].

Rabban Gamliel was sitting and expounding while R. Yehoshua stood on his feet, until all the people murmured and sait to Huspit the turgeman [the interpreter]: “Stop!” and he stopped. They said: “How long will he [Rabban Gamliel] go on distressing [R. Yehoshua]? He distressed him last year on Rosh Hashanah.[42] He distressed him in [the matter of] the firstling, in the incident involving R. Zadoq.[43] Now he distresses him again. Come, let us depose him. Whom will we raise up [in his place]? Shall we raise up R. Yehoshua? He is involved in the matter. Shall we raise up R. Aqiva? Perhaps he [Rabban Gamliel] will harm him, since he has no ancestral merit. Rather, let us raise up R. Eleazar b. Azariah, for he is wise, and he is wealthy, and he is tenth [in descent] from Ezra. He is wise—so that if anyone asks a difficult question, he will be able to answer it. He is wealthy—in case he has to pay honor to the emperor. And he is tenth in descent from Ezra—he has ancestral merit and he [Rabban Gamliel] will not be able to harm him.”

They said to him: “Would our Master consent to be the head of the academy?” He said to them: “Let me go and consult with the members of my household.” He went and consulted his wife. She said to him: “Perhaps they will reconcile with him and depose you?” He said to her: “There is a tradition, One raises the level of holiness but does not diminish it [m. Menah. 11:7].”[44] She said to him: “perhaps he [Rabban Gamliel] will harm you?” He said: “Let a man use a valuable cup for one day even if it breaks on the morrow.” She said to him: “You have no white hair.” That day he was eighteen years old. A miracle happened for him and he was crowned with eighteen rows of white hair . . .

It was taught [in a baraita]: That day they removed the guard of the gate and gave students permission to enter. For Rabban Gamliel had decreed: “Any student whose inside is not like his outside may not enter the academy.” That day many benches were added. R. Yohanan said: “Abba Yosef b. Dostenai and the sages disagree. One said, ‘Four hundred benches were added.’ And one said: ‘Seven hundred benches were added.’”

Rabban Gamliel became distressed. He said: “Perhaps, God forbid, I held back Torah from Israel.” They showed him in a dream white casks filled with ashes.[45] But that was not the case, they showed him [the dream] only to put his mind at ease [but he really had held back Torah].

It was taught [in a baraita]: They taught [Tractate] Eduyyot on that day (and anywhere that it says “on that day” [in the Mishnah]—[refers to] that day [when R. Eleazar was appointed head of the academy]. And there was not a single law pending in the academy that they did not resolve . . .

Rabban Gamliel said: “I will go and appease R. Yehoshua.”[46] When he arrived at his house, he saw that the walls of his house were black. He said to him: “From the walls of your house it is evident that you are a smith.” He said to him: “Woe to the generation whose chief you are, for you do not know the distress of the scholars, how they earn a living and how they subsist.” He said to him: “I apologize to you. Forgive me.” He [R. Yehoshua] paid no attention to him. [Rabban Gamliel said,] “Do it for the honor of my father’s house.” He said to him: “You are forgiven” . . .

They said: “What shall we do? Shall we depose him [R. Eleazar b. Azariah]? There is a tradition, “One raises the level of holiness but does not diminish it” [m. Menah. 7:11]. “Shall this master expound on one Sabbath and that master on the next? He [Rabban Gamliel] will not accept that since he will be jealous of him.” Rather, they ordained that Rabban Gamliel would expound three Sabbaths and R. Eleazar b. Azariah one Sabbath. (This explains the tradition, “Whose Sabbath was it? It was [the Sabbath] of R. Eleazar b. Azariah” [t. Sotah 7:9]. And the student [who asked the original question] was R. Shimon bar Yohai.)[47]

Whereas in the pre-Neusner era this narrative would essentially have been taken at face value (with the exception of the supernatural detail about Rabbi Eleazar b. Azaria’s hair turning white), and considered a story from tannaitic times about a conflict between rabbis of the immediate post-temple times, scholars today are more skeptical as to its provenance and more restrained in drawing detailed historical conclusions from it. While it is purportedly a tannaitic tradition (baraita) featuring Palestinian rabbis, it seems to reflect particular Babylonian conditions of a later period, such as large academies, concern over matters related to the leadership of the academy, and the view of wives as an obstacle to a career within the academy.[48] Furthermore, cross-references to and quotation of other rabbinic sources seem to indicate redactional authorship or reworking.[49]

While no longer understood to reflect a historical dispute between Rabban Gamliel and R. Yehoshua in the first century, most scholars would understand it to reflect Babylonian rabbinic culture of a later period, taking it as evidence of a tendency toward dynastic succession in the appointment of head of the academy and an internal rabbinic concern over the leadership style and general policy of the academies. The motif of guards and their removal from the entrance of the academy may be understood to reflect a conflict over whether Torah study should be accessible to all or restricted to a limited number of worthy students. From the deliberations regarding whom to appoint as head of the academy in place of Rabban Gamliel may be deduced that wealth, learning, and ancestral merit were considered important qualifications for leadership in the Babylonian academy.

Following this presentation of the rabbinic understanding and development of biblical tradition as evidenced in the Mishnah and the two Talmuds, we will now turn to the rabbis’ interpretation of the Bible and the assumptions that underlie it.

Study Questions

1. What are the characteristics of the Mishnah and how have scholars explained them?

2. Explain the different scholarly theories about the purpose and function of the Mishnah.

3. In what ways has recent scholarship on orality influenced the view of how the Mishnah developed and was transmitted?

4. Describe the characteristics and particular concerns/motifs of the Babylonian Talmud as compared to the Mishnah and the Palestinian Talmud.

5. What are the problems involved in using rabbinic sources for the purpose of historical reconstructions?

Suggestions for Further Reading

The Mishnah and Tosefta

Shanks Alexander, E. Transmitting Mishnah: The Shaping Influence of Oral Tradition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Kraemer, D. “The Mishnah.” In The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, edited by Steven T. Katz, 299–315. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Mandel, P. “The Tosefta.” In vol. 4 of The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, edited by Steven T. Katz, 316–35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

The Palestinian Talmud

Bokser, B. M. “An Annotated Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Palestinian Talmud.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 19.2, edited by H. Temporini and W. Haase, 139–256. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979.

Moscovitz, L. “The Formation and Character of the Jerusalem Talmud.” In vol. 4 of The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, edited by Steven T. Katz, 663–77. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

The Babylonian Talmud

Goodblatt, D. “The Babylonian Talmud.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 19.2, edited by H. Temporini and W. Haase, 257–336. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1979.

Kalmin, R. L. “The Formation and Character of the Babylonian Talmud.” In vol. 4 of The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, edited by Steven T. Katz, 840–76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Rubenstein, J. L. Talmudic Stories: Narrative Art, Composition, and Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

———. Stories of the Babylonian Talmud. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

History and Culture of Babylonian Jewry

Gafni, I. “Babylonian Rabbinic Culture.” In Cultures of the Jews: A New History, edited by D. Biale, 223–65. New York: Schocken, 2002.

———. “The Political, Social, and Economic History of Babylonian Jewry.” In vol. 4 of The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, edited by Steven T. Katz, 792–820. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Rubenstein, J. L. The Culture of the Babylonian Talmud. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Cohen, From the Maccabees, 218–21; Kraemer, “Mishnah,” 311–13.↵

- See Gafni, “Rabbinic Historiography,” 295–312.↵

- For a more detailed survey of the content of the Mishnah, see Stemberger, Introduction, 110–18.↵

- m. Ber. 1:1–2. My translation.↵

- For a more detailed description of the Mishnah’s content and characteristics, see Goldberg, “Mishna,” 227–33; Goldenberg, “Talmud,” 131–34; Kraemer, “Mishnah,” 299–311; Neusner, Invitation to the Talmud, 28–37; Stemberger, Introduction, 110–18.↵

- Safrai, “Halakha,” 146–63. For a discussion of the shift in scholarly consensus, see Halivni, Midrash, 18–21.↵

- For a survey, see Stemberger, Talmud and Midrash, 133–39.↵

- Shanks Alexander, Transmitting Mishnah, 167–73.↵

- Ibid.↵

- Walfish, “Mishnah,” 153–189.↵

- See Lieberman, Greek/Hellenism in Jewish Palestine, 83–99.↵

- See, for example, Goldberg, “Mishna,” 211–51.↵

- Shanks-Alexander, Transmitting Mishnah, 1–76.↵

- Fraade, “Literary Composition,” 33–51; Jaffee, “Oral Tradition,” 3–32.↵

- For a survey of the Tosefta, see Goldberg, “Tosefta,” 283–302; Neusner, Invitation to the Talmud, 70–95; Stemberger, Introduction, 149–63; Mandel, “Tosefta,” 316–35.↵

- For a survey of the relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta, see Hauptman, Rereading the Mishnah, 14–16; Fox and Meacham, Introducing Tosefta.↵

- Hauptman, Rereading the Mishnah, 1–30.↵

- b. Gitt. 6a.↵

- b. Ket. 110b–111a. The contemporary anti-Zionist Satmar hasidim appeal to this passage in order to deter Jews from moving to the modern State of Israel.↵

- t. Avod. Zar. 5. Similarly in Pirqe R. Eliezer 8: “Even when there are Sages and righteous outside the land, and only a shepherd or a herdsman in the land, it is the shepherd or the herdsman who is to declare the New Year. And even if you have prophets outside the Land of Israel, and commoners in the Land, authority to proclaim the calendar rests with the commoners in the Land of Israel.” On the competition between the land of Israel and Babylonia, see Gafni, Land, Center.↵

- That the anonymous layer postdates the amoraic sayings was suggested by David Weiss Halivni and Shamma Friedman independent of each other in the 1970s. A summary of Halivni’s hypothesis in English appears in Midrash, 76–104, and the latest revision of his dating of the anonymous layer is found in “Aspects,” 339–60.↵

- b. Ber. 2a.↵

- For surveys of the Babylonian Talmud, see Goldberg, “Babylonian Talmud,” 323–66; Goldenberg, “Talmud,” 129–75; Goodblatt, “Babylonian Talmud,” 257–336; Halivni, Midrash, 66–104; Kalmin, “Formation and Character,” 840–76; Neusner, Invitation to the Talmud, 96–270; Stemberger, Introduction, 164–224.↵

- For a more detailed description, see Steinsaltz, Reference Guide, 48–59.↵

- Halivni, Midrash, 86–92.↵

- Kraemer, Mind, 99–139.↵

- Halivni, Midrash, 87.↵

- Halivni, “Aspects,” 346.↵

- Halivni, Midrash, 76–92.↵

- See for instance Friedman, “Good Story,” 71–100.↵

- Hauptman, Development, 227–50.↵

- Rubenstein, Stories; Rubenstein, Culture; Rubenstein, Talmudic Stories.↵

- For the tension between Torah study and marriage, see b. Yebam. 62b–63a; b. Ket. 61b–64a, and Boyarin, Carnal Israel, 142–66; Satlow, Jewish Marriage, 3–41; Rubenstein, Culture, 102–22. On the tension caused by the ideal to study Torah on the one hand and the need to earn a living on the other, see b. Taanit 21a, and Licht, Ten Legends, 181–206; Rubenstein, Stories 41–61, and also b. Shabb. 33b–34a, and Rubenstein, Talmudic Stories, 105–38.↵

- See, for instance, Neusner, Making the Classics.↵

- Hayes, Between the Talmuds, 9–17; Kalmin, Sages, xiii–17; Kalmin, “Formation and Character,” 843–52; Kraemer, Mind, 20–25.↵

- For a survey of the Palestinian Talmud, see Bokser, “Palestinian Talmud,” 139–256; Goldberg, “Palestinian Talmud,” 303–22; Moscovitz, “Formation and Character,” 663–77.↵

- Gray, Talmud in Exile.↵

- See for instance Neusner, Development of a Legend; Neusner, Rabbinic Traditions. See also Green, “What’s in a Name?” 77–96.↵

- See Fraenkel, Darkhe haaggadah.↵

- See Goodblatt, “Rehabilitation” 31–44; Kalmin, “Rabbinic Literature,” 187–99; Kraemer, “Rabbinic Sources,” 201–12.↵

- Metaphors of war are often used to describe rabbinic debates over Torah. See Rubenstein, Culture, 59–64.↵

- By telling him to appear before him with his staff and money on the day that according to Rabbi Yehoshua was Yom Kippur (b. Rosh Hash. 25a and m. Rosh Hash. 2:8–9).↵

- This refers to a similar story in which R. Yehoshua and Rabban Gamliel answer R. Zadoq’s question about a blemished firstling in opposite ways, and the people tell Huspit to stop (b. Bek. 36a).↵

- R. Eleazar applies this principle of temple law—that once an object or sacrifice takes on a certain level of holiness, it cannot be reduced to a less holy state—to his situation. Once he has been promoted to the position of head of the academy he will not be demoted.↵

- The casks with ashes symbolize unworthy students whose insides (personal character) are as worthless as ash.↵

- Apparently he realizes that the presence of numerous students helps to resolve disputes and problems of law and therefore resolves to change his ways.↵

- Translation and explanatory comments are taken from Rubenstein, Rabbinic Stories, 99–103. For analyses of the story, see Goldenberg, “Deposition,” 167–90; Steinmetz, “Must the Patriarch,” 163–90; Rubenstein, Stories, 77–90.↵

- Rubenstein, Stories, 77–90.↵

- Rubenstein, Culture, 102–21.↵