3

Rabbinic Biblical Interpretation—Midrash

The rabbis’ expansions on the Bible always take as their point of departure something in the verse that appeared problematic to them. Such problems could be anything from a textual detail—an unusual word, grammatical form, or spelling, a repetition, omission, or a contradiction between two verses—to wide-ranging theological problems caused by actions by the biblical characters or by God not in keeping with the moral code of the rabbis. For instance, the story of the sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22 raises the theologically difficult question of why a good and omniscient God would test Abraham by commanding him to kill his beloved son, Isaac, thus necessitating interpretation. A completely different kind of difficulty—but nevertheless one that needed to be addressed in the eyes of the rabbis—is the reality of the different rules for the preparation of the Passover lamb in Exodus and Deuteronomy. According to Deut. 16:7, it should be boiled, whereas Exod. 12:9 says that it should be roasted over fire, thus creating a contradiction that needed to be solved.

While a modern reader of the Bible may likewise be troubled by the theological problem raised by God’s command to sacrifice Isaac, he or she is unlikely to be bothered by repetitions and contradictions between different parts of the Bible or by odd wordings and unusual spellings. Most modern readers would simply attribute these things to the fact that the Bible consists of a number of different sources that date from different time periods and to the change that language naturally undergoes over time.

Assumptions about the Biblical Text

It is evident, then, that the difficulties perceived in the biblical text are dependent on the reader’s understanding of the Bible and his or her expectations of it. In spite of the great variety of styles, genres, and interpretive methods of ancient biblical interpreters, a common approach nevertheless seems to underlie their interpretations and they seem to share a common set of assumptions about the biblical text, as observed and described by James Kugel. He identifies four fundamental assumptions about the Bible that underlie all ancient biblical interpretation. First, ancient exegetes seem to take for granted that the Bible is a fundamentally cryptic document, that is, they assume that behind the apparent meaning there is some hidden esoteric meaning. Even though it says X, what it really means is Y, or while Y is not openly stated, it is hinted at or implied in X. When Isaac says in Gen. 27:35 that Jacob “came with deceit” and took the blessing that rightly belonged to his brother Esau, it really means that he acted with wisdom (Gen. Rab. 67.4). The belief that it had been God’s will all along that Jacob gain his father’s blessing justifies Jacob’s conduct since he was only doing what was necessary to carry out the divine plan. The same assumption that the Bible is a cryptic document allowed early Christian interpreters to claim that the suffering servant in Isaiah 52 alludes to Jesus.

The second assumption is that the Bible is a fundamentally relevant text. It is not primarily a book about Israel’s ancient history but speaks to its readers’ present situation and was written down for later generations to learn moral lessons from it. The patriarchs are held up as models of conduct, and their lives considered a source for inspiration. It is this view of the lives of the patriarchs as models of conduct that necessitated the reinterpretation of Jacob’s taking of the blessing and his lying to his father. The idea that all of the Bible could be applied to the present made even prophecies and genealogies relevant to the rabbinic present.

The third assumption is that the Bible is perfect and perfectly harmonious. This means that it contains no mistakes (anything that might look as a mistake is only an illusion and will be clarified by proper interpretation) or inconsistencies between its various parts and that any biblical passage might illuminate any other. Taken to its extreme, the idea of the Bible as perfect led to the view that every detail of the text was significant. Nothing is said in vain or for rhetorical flourish and there is divine intention behind every detail. Accordingly, unusual words or grammatical forms, repetitions or omissions, and juxtapositions of one event to another were understood as potentially significant and deliberately placed there by God as an invitation to interpretation.

For instance, the fact that only Abraham is mentioned in Gen. 12:11, even though it is clear that he and Sarah were travelling together, calls for an explanation: “When he was about to enter Egypt, he said to his wife, Sarai, ‘I know that you are a beautiful woman.’” Assuming that the Bible is perfect and that there is divine intention behind every detail, the verse should have read: When they were about to enter Egypt. Accordingly, the fact that only Abraham is mentioned led the rabbis to suggest that Abraham had hidden Sarah in a box (Gen. Rab. 40.5). Similarly, when the Israelites’ departure from Egypt is mentioned for the third time in Exod. 32:11 in the passage about the sin with the Golden Calf, it cannot merely be a piece of information. Rather, Moses mentions it here in order to remind God that Israel has only recently left Egypt where calf worship is common, and accordingly he must understand that he cannot immediately expect impeccable behavior from the Israelites (Exod. Rab. 43.9). Ultimately, the perfect nature of the Bible also included the conduct of biblical heroes and the content of its teachings, so that they were assumed to be in accordance with the interpreter’s own ideas and standards of conduct.

The fourth assumption is that the Bible in its entirety is divinely inspired: that is, not only the parts that contain divine speeches introduced with “And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying . . .” or prophecies, but also the parts that may appear to be of human fashioning, such as the intrigues in King David’s court, or supplications directed to God, are actually divinely inspired. Even if Moses or King Solomon are said to be the authors of this or that biblical book, they are merely a human conduit of the divine word.

As a consequence of these assumptions, ancient biblical interpreters scrutinized every detail of the biblical text in search of hidden meaning. Any apparent contradiction, superfluous detail or repetition, any action by God or by a biblical hero not in accordance with the rabbis’ expectations, were seen by them as an invitation from God to look deeper into the text and discover its true meaning intended by God.[1]

This common set of assumptions about the biblical text was not unique to the rabbis but shared by all ancient interpreters, including the Christians. If the Christian interpreters often reached different conclusions from those of the rabbis this is because they were driven by a different set of anxieties. While the Jews were anxious to find evidence in the Bible that they remained God’s chosen people in spite of Christian claims to the contrary, the Christians needed to defend their status as God’s chosen people and demonstrate that the New Testament was the key to understanding the Hebrew Bible.[2]

The assumptions about the biblical text outlined above did not originate with the rabbis and Christian interpreters in the first centuries CE. but underlie much of earlier interpretation as well. The oldest form of biblical interpretation is found within the Bible itself where biblical authors frequently revised earlier texts in order for them to remain relevant or better conform to the worldview of later times. A classic example is 1 and 2 Chronicles, whose author retells the books of Samuel and Kings and reshapes them by omitting some things and adding others. In a similar fashion, the author of Genesis 20 essentially retells the story of Abraham and Sarah in Egypt (Gen. 12:10-20), but places it in Gerar, removing or glossing over elements that seemed offensive to him. In chapter 12, for instance, Abraham asks Sara to lie and tell the Egyptians that she is his sister rather than his wife because he is afraid that they will otherwise kill him, a behavior not fitting a patriarch and a model of conduct. As a result, Sarah is “taken into Pharaoh’s palace,” and in return Abraham is given sheep, oxen, camels, and slaves. In chapter 20, by contrast, Sarah is saved from becoming the wife of the king of Gerar through direct intervention from God, who reveals to him that Sarah is Abraham’s wife. To make sure nobody gets the wrong impression of Abraham, chapter 20 also adds that in addition to being Abraham’s wife, Sarah was also his sister.

As with Chronicles, interpretation here takes the form of a retelling of a biblical story where elements perceived as troublesome or offensive are simply replaced, a practice that developed into a genre known as “rewritten” Bible. This practice can operate on the level of a single word, whereby a term whose meaning had shifted and was no longer widely understood is replaced by a more common word, or on the level of a whole phrase, whereby an ideologically problematic phrase such as “with deceit” as a description of Jacob’s actions was replaced with the more acceptable “with wisdom.” This practice of substitution or replacement rather than openly commenting on a biblical verse produces an interpretation that is barely discernable. Only someone who is very well acquainted with the Bible would recognize the somewhat odd expression in 2 Chron. 35:13, “They cooked the Passover lamb with fire,” as a subtle harmonization of Exod. 12:9, stating that the Passover lamb should be roasted over fire, and Deut. 16:7, saying that it should be boiled.

Likewise, the passage from the Wisdom of Solomon (first or second century BCE), “She [Wisdom] brought them over the Red Sea, and led them through the deep waters; but she drowned their enemies and cast them up from the depth of the sea,” may be recognized as a harmonization of the contradiction created by the statement in Exod. 15:5, “They [Pharoh’s army] went down into the depths like a stone,” and Exod. 14:30, “Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the shore of the sea.” Since both statements must be true, the Wisdom of Solomon explains that the Egyptians at first sank to the bottom of the sea and were then thrown back up on the shore.[3] Rabbinic interpretation of the Bible, however, only rarely took the form of such “rewritten Bible.” Typically, the rabbis would compile interpretive comments and attach them to biblical verses in a way that made their comments easily distinguishable from the biblical verse.

The approach to the biblical text that produces these kinds of interpretations is often referred to as midrash, a word derived from the Hebrew root darash whose basic meaning is “to seek out” the will of God. In the early parts of the Bible, it is often used in the sense of asking God, or exploring his will through consulting Moses or a prophet (Gen. 25:22; Exod. 18:15). In later times, when prophecy was believed to have ceased,[4] there was a shift in focus to interpreting the text of the Bible, which was then considered the only place where God’s will was to be found. In this broad sense of biblical interpretation, midrash includes pre-rabbinic interpretations (such as, for instance, the Wisdom of Solomon) as well as the early Aramaic translations of the Bible (targumim). In addition to interpretive activity, the term midrash also denotes the corpus in which these interpretations are preserved as well as the smallest interpretive unit in such a corpus.[5]

Textual Problems

Although biblical interpretation was by no means an invention of the rabbis, it reached its peak during the rabbinic period. Rabbinic biblical interpretation often goes beyond the simplest solutions to the difficulties perceived in the biblical text and commonly involves the reconstruction of events and conversations between biblical characters. For instance, literally translated, Gen. 4:8 reads: “Cain said to his brother Abel . . . and when they were in the field, Cain set upon his brother Abel and killed him,” an odd wording that suggests something is missing. What Cain said to Abel is somehow omitted, and assuming that the text was deliberately fashioned in this way to invite interpretation, the rabbis reconstructed the omitted conversation, explaining the reason for Abel’s murder by suggesting that a quarrel between the brothers preceded it:

Cain set upon his brother Abel [and killed him] [Gen. 4:8]. About what did they quarrel? “Come,” said they, “let us divide the world.” One took the land and the other the movables. The former said: “The land you stand on is mine,” while the other retorted: “What you are wearing is mine!” One said: “Strip!” the other retorted: “Fly” [off the ground]. Out of this quarrel Cain set upon his brother . . . Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in Rabbi Levi’s name: Both took land and both took movables, so what did they quarrel about? One said: “The temple must be built in my area,” while the other claimed: “It must be built in mine!” For it is written, And when they were in the field [Gen. 4:8]. Now, “field” refers to the Temple, as you read, Zion [that is, the temple] shall be plowed as a field [Micah 3:12]. Out of this argument Cain set upon his brother . . . Judah b. Rabbi said: Their quarrel was about the first Eve. Rabbi Aibu said: The first Eve had returned to dust, so what, then, was their quarrel about? Rabbi Huna said: An additional twin was born with Abel, and each claimed her. The one claimed: “I will have her, because I am the firstborn,” while the other maintained: “I must have her, because she was born with me.”[6]

At first glance, the suggestion that Cain and Abel quarreled over the temple—which did not yet exist in their time—may seem naïve, but because the rabbis were mainly interested in the timeless truths and moral lessons that could be drawn from the biblical text, they did not shy away from blatant anachronisms. They also tend to employ very specific examples, and sometimes it is necessary to translate them into more general categories in order to make sense of them. If “land and movables” is taken to represent property in general, the temple as symbolizing power or career, and “the first Eve” as women in general, their suggestions appear less naïve and even insightful. Being common, timeless issues of contention between people, a quarrel over them appears as an altogether plausible reason behind the murder of Abel.

Theological Problems

At other times, the biblical text raised problems of a theological nature precipitating interpretation. For instance, in the story about Cain and Abel in Gen. 4:1-10, God accepts Abel’s sacrifice but rejects Cain’s for no obvious reason, making God appear arbitrary or outright unjust. This difficulty provoked various interpretations, some of which attempt to justify God while others do not hesitate to criticize him. Focusing on a slight difference in wording in the Bible’s description of their respective sacrifices in Gen. 4:3-4, the rabbis suggest that Cain’s sacrifice was indeed inferior to Abel’s, because it says that Abel sacrificed the “choicest of the firstlings of his flock”(Gen. 4:4) whereas Cain simply offered a sacrifice. “Cain brought an offering to the Lord,” obviously not bothering to give the best to God. As a consequence, God’s rejection of Cain’s sacrifice was neither arbitrary nor unjust but completely justified.[7] Another interpretation, however, does not shy away from the idea that God shares the responsibility for Abel’s death:

When the Holy One, blessed be He, asked Cain: “Where is your brother Abel?” He said: “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper? [Gen. 4:9]. You are the one who watches over all living beings, and you ask this of me!” This can be compared to a thief who stole things at night and got away. In the morning the gatekeeper caught him and asked: “Why did you steal these things?” The thief replied: “I stole but I did not neglect my job. But you whose job it is to keep watch at the gate, why did you neglect your job? And now, you speak to me like this!” Similarly, Cain said: “Yes, I killed him, but you created the evil inclination in me. You are the keeper of everything and yet you let me kill him! It is you who killed him, for had you accepted my sacrifice as you accepted his, I would not have been jealeous of him.”[8]

Rather than defending God’s actions by claiming that Cain’s sacrifice was of inferior quality, the rabbis, through a parable, play with the idea that God is to blame for Abel’s death. In order to shift the blame away from himself to God, Cain advances three arguments: First, God created the evil inclination, making him ultimately responsible for all evil actions that humans do; second, he did not prevent him from killing his brother; and third, he bears responsibility for the conflict between the brothers because he accepted the sacrifice of one but not of the other.

Cain argues cleverly and may at first sight appear to have a point, but by comparing him to a thief the author of the parable hints at a flaw in his logic. A criminal can hardly be excused by arguing that he is a skilled criminal, and his argument that the watchman alone is responsible for everything that happens does not hold up either. Relieving all the city’s inhabitants of any responsibility whatsoever and placing it all on the gatekeeper is not reasonable. Each individual person cannot do whatever he feels like doing and then argue that he is blameless because the gatekeeper did not prevent him from doing what he did. To argue that the world would have been better had God created humans without an inclination to do evil may have some validity as a philosophical argument, but given our existence as it is, humans must accept responsibility for their actions. Nevertheless, Cain’s arguments seem to reflect doubts on the part of the author of the parable, and the claim that God is to blame—because his rejection of Cain’s sacrifice made Cain feel rejected and angry—remains unanswered. The parable is ambiguous, struggling with the problem of human evil and divine responsibility rather than giving a clear-cut answer.[9]

A similar, even-more-daring example, which illustrates that the rabbis did not hesitate to criticize God, is the parable about the two athletes wrestling before the king:

The Lord said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?” [Gen. 4:9]. It is difficult to say this and it is impossible to utter it plainly. It can be compared to two athletes wrestling before the king. Had the king wished, he could have separated them, but he did not and one overcame the other and killed him. The dying man cried: “Let my cause be pleaded before the king!” Similarly, the voice of your brother’s blood cries out against Me from the ground!” [Gen. 4:10].[10]

Instead of reading Gen. 4:10 as God’s reproach against Cain, the Hebrew preposition ’elai, “to me” is read as ‘alai, “against me” (replacing the Hebrew letter alef with ayin), transforming it into an accusation against God, “your brother’s blood cries out against me [God] from the ground!”

Another interpretation evolves around the peculiar fact that the word “blood” and the verb “cry” that goes with it appear in the plural, “your brother’s bloods are crying” (qol deme ahikha tsoaqim). Since “blood” does not usually appear in the plural in Hebrew, the rabbis felt the need to explain it and suggest that the verse does not refer only to Abel’s blood but also to the descendants he would never have:

Rabbi Judan, Rabbi Huna and the [other] rabbis commented [on the plural form]: Rabbi Judan said: It is not written, “your brother’s blood [sing.] [dam ’ahikha], but your brother’s bloods [plur.] [deme ’ahikha], that is, his blood and the blood of his descendants.”[11]

According to this interpretation, Cain may be considered guilty of murdering not only Abel but also the descendants that the latter never would have.

Another example of a theological difficulty is the problem raised by God’s decision to test Abraham in Gen 22:1. That God would test the righteous Abraham by commanding him to sacrifice his beloved son, Isaac, seemed cruel and offensive to the rabbis who were convinced that God was both good and omniscient. Since God would know in advance how Abraham would act, there was no need for such a cruel test, a test that also involves the innocent Isaac. Accordingly, some of the rabbinic explanations of this passage claim that the intention of the test was not to prove to God that Abraham would obey, but to demonstrate to others Abraham’s obedience and loyalty.[12] According to others, the test was caused by Satan’s insinuation that Abraham loved his son more than he loved God, thus making it necessary for God to test Abraham in order to refute Satan’s slander.[13]

However, in most rabbinic interpretations of the story, it is not Abraham but Isaac who is the hero of the story and the one to provoke the test. The phrase that introduces the story, “After these things, God tested Abraham,” can also be taken to mean “after these words,” providing the rabbis with the opportunity to introduce another quarrel, this time between Abraham’s sons, Isaac and Ishmael. The brothers brag and both try to portray themselves as the one most beloved by God:

Isaac and Ishmael were engaged in a controversy: the latter argued: “I am more beloved than you, because I was circumcised at the age of thirteen,” while the other retorted, “I am more beloved than you, because I was circumcised at eight days.” Said Ishmael to him: “I am more beloved, because I could have protested, yet did not.” At that moment Isaac exclaimed: “O that God would appear to me and ask me to cut off one of my limbs! Then I would not refuse.” Said God: “Even if I ask you to sacrifice yourself, you will not refuse.”[14]

According to this interpretation, God initiates the test in direct response to Isaac’s words, thus solving or at least mitigating the problem of why a good and omniscient God would demand such a horrible sacrifice.

Exegesis or Ideology?

One may legitimately ask whether these interpretations really evolved in response to difficulties in the biblical text, or whether they were rather generated by some outside concerns. Indeed, earlier scholarship on rabbinic midrash tended to focus precisely on its ideological side, assuming that the interpretations were generated by the rabbis’ political views or political agenda, or regarding it as bits of free-floating popular folklore that had more or less randomly been attached to a given biblical verse. Jacob Neusner, for instance, views rabbinic interpretation as wholly dictated by ideology with the biblical verse merely serving as a pretext. His approach to midrash as a source for the reconstruction of the development of rabbinic Judaism makes him focus on the redaction of each midrashic collection and the ideology and worldview that they in his opinion reveal, largely ignoring the interpretive aspects.[15]

In recent years, however, increasing attention has been given to the exegetical nature of midrash, leading to the view that rabbinic interpretations are indeed the outcome of the rabbis’ grappling with the biblical text. This approach is influenced by insights from modern literary theory, according to which meaning of a text is established in the encounter between text and reader, and is at least in part due to the encounter between midrash and modern literary theory that occurred as a result of an increasing interest in midrash as the subject of university studies in the 1980s. Literary theorists describe literary works as consisting of bits and fragments that are pieced together in the process of reading whereby the reader, consciously or unconsciously, fills in any implicit or missing detail about an event, motive, or causal connection.[16] Such filling in of gaps perceived in the text ranges from an automatic filling in of small details, which are obvious from the context, to adding more complex lines of argument based on information from other parts of the story. If modern texts contain gaps, it is all the more true of the biblical text that was composed by many different authors over a long period of time.[17]

Inspired by this insight, an increasing number of scholars of midrash argue that rabbinic interpretations were generated by interaction between the biblical text and the rabbinic reader with a specific set of assumptions about the Bible. While not denying the role of ideological, theological, and political factors in generating biblical interpretation, midrash was increasingly understood to be the outcome of the rabbis’ attempts to make sense of the biblical text and to fill in gaps that they perceived in the text.[18] The material with which the rabbis filled the gaps derives from other parts of the Bible and from the rabbis’ own experiences, background, and worldview, their “ideological code,” in Daniel Boyarin’s words.

Thus, the rabbis’ experience told them that conflicts between people often concern property, power, and women, so in response to the gap in Gen 4:8 they constructed an argument between Cain and Abel over these things, supplying the information that seems to be missing from the biblical text. In a similar process, the attempt to solve the theological problems that the rabbis perceived in Genesis 22, together with close attention to the details of the biblical text, produced the idea that God’s commandment to sacrifice Isaac was the result of a provocation from Isaac. Because of their belief that God was good and omniscient, the rabbis found his commandment to sacrifice Isaac offensive, and in the introduction to the story, “it happened after these things,” they found an irregularity that hinted at the problem’s solution. Reading with the assumption that every detail is significant, the phrase, “after these things,” may appear somewhat odd and one may wonder, after which things? The phrase could be understood to refer back to the events described in the previous chapter, but the Hebrew word for “thing” (davar) can also mean “word,” and from this sense the idea of a quarrel between Isaac and Ishmael arose, giving a rationale for the test while exonerating God.

At other times, the rabbis used material from other parts of the Bible to solve difficulties that they perceived in the biblical text, letting verses from different parts of the Bible shed light on one another. For instance, the idea that Laban was an archenemy of Israel who attempted to kill Jacob, expressed in a large number of midrashim and targumim,[19] but perhaps best known from the Passover Haggadah, is very likely the outcome of such an intertextual reading where a number of verses from different parts of the Bible were juxtaposed: “Go and learn what Laban the Aramean attempted to do to our father Jacob! Pharaoh decreed only against the males but Laban attempted to uproot everything, as it is said, An Aramean destroyed my father. Then he went down to Egypt” [Deut. 26:5]. Modern Bible translations usually render the quote from Deut. 26:5, “My father was a wandering Aramean,” but the Haggadah and all targumim and early midrashim understand it to mean that Laban attempted to kill Jacob. While the phrase ’arami ‘oved ’avi could grammatically be taken to mean “an Aramean destroyed my father,” it is hardly the sense that immediately comes to mind and it certainly does not fit the context of Deut. 26:5. Very likely, this understanding is also, at least in part, generated by a problem perceived in the biblical text. Given that it is Laban who is elsewhere known as an “Aramean” (Gen. 25:20, 31:20, 31:24)—in fact he is the best-known Aramean in the Bible—the rabbis probably found the designation of Jacob as an Aramean odd and the epithet better suited for Laban. Once “Aramean” was connected to Laban and the phrase understood to mean that an Aramean attempted to destroy Jacob, the rabbis likely found hints to Laban’s evil intentions in the story about Jacob’s flight from Haran: “So he [Laban] took his kinsmen with him and pursued him a distance of seven days, catching up with him in the hill country of Gilead. But God appeared to Laban the Aramean in a dream by night and said to him, ‘Beware of attempting anything with Jacob, good or bad.’ Laban overtook Jacob . . .” (Gen. 31:23-25). The words for “catching up” and “overtake” have hostile connotations in biblical Hebrew, and a reading of these verses in conjunction with Deut. 26:5 likely generated the idea that Laban attempted to kill Jacob, and by extension, all of Israel. Such a reading of Deut. 26:5 and Gen. 31:23-25 in light of each other is evidenced in two late midrashim,[20] but seems to underlie the earlier targums and midrashim as well.[21]

Granted that the rabbis found difficulties in the biblical text due to an underlying ideology or assumptions about the biblical text, their understanding of the biblical text very likely also affected their ideology and theology. Thus, rather than regarding rabbinic biblical interpretation as a reflection of an already existing ideology, it should be seen as the outcome of a dialogue between text and reader conditioned by the prevailing assumptions of the rabbinic reader. If this reading seems strange or far-fetched to us, that is because we do not share the exegetical assumptions of the rabbis. Midrash, says Boyarin, is the “product of a disturbed exegetical sense” only if we recognize that all exegetical senses are disturbed, including our own.[22]

While most rabbinic interpretations clearly evolve around a difficulty in the biblical text, the connection to problems becomes less evident in later midrashic collections where the interpreter sometimes betrays signs of first having thought of an exposition and then having gone looking for a verse to attach it to. Kugel describes the development in the following way: “[T] he text’s irregularity is the grain of sand which so irritates the midrashic oyster that he constructs a pearl around it. Soon enough—pearls being prized—midrashists begin looking for irritations and irregularities, and in later midrash there is much material, especially list-making and text-connecting, whose connection with ‘problems’ is remote indeed; in fact, like many a modern-day homilist, the midrashist sometimes betrays signs of having first thought of a solution and then having gone out in search of a problem to which it might be applied.”[23] Nevertheless, the best starting point when reading ancient biblical interpretations is to first attempt to find the problem that bothered the ancient interpreters. Only when that difficulty is identified are we likely to comprehend the interpretation.

At times, rabbinic interpretations appear very strained and one may wonder whether they believed that the biblical text really meant what they asserted it to mean. In order to explain away Jacob’s lie in Gen. 27:19, where he claims to be the first-born in order to secure for himself the blessing that rightly belongs to Esau, the rabbis engage in what would seem to be a rather far-fetched and creative exegesis. Exploiting the fact that the biblical text had no punctuation or capital letters, as well as the fact that the verb “to be” is frequently omitted in biblical Hebrew, they reinterpreted Isaac’s question and Jacob’s response in Gen. 27:18-19: “Who are you, my son?” “I am Esau, your firstborn,” to mean: “Who are you? My son? “I am. [But] Esau is your firstborn.”[24]

It is obvious that this interpretation is meant to excuse Jacob and improve his image. To a modern reader, this reading appears as an outright manipulation of the biblical text, and one may wonder if the rabbis really believed that the biblical text meant what they claimed it meant. There is often a certain playfulness to midrash, and it is evident that the rabbis were aware that the biblical text on the surface at times meant something else than what they made it out to mean through their interpretations. On a deeper level, though, they believed that the meaning they found in the biblical text was the true one—the one that God had intended. In the view of the rabbis, it would be unthinkable for God to give the blessing to the wrong person, and for Isaac to be unaware to whom he gave his blessing. They believed that the entire story about Jacob’s deceit and Isaac’s credulity only took place on a superficial level and that God had deliberately designed the story in this way, hinting by means of irregularities in the text that interpretation was in order to disclose the true meaning of the text. The ultimate purpose of biblical interpretation, then, was to reveal the true meaning, hidden under the surface of the biblical text.[25]

Parables as Biblical Interpretation

One tool with which the rabbis discovered hidden meanings in the biblical text was parables: “Do not treat the mashal [parable] lightly,” they said, “for by means of a mashal a person is able to understand the words of Torah.”[26] Although there are different kinds of parables, the vast majority of rabbinic parables are preserved in exegetical contexts and serve as tools for scriptural exegesis. Through such fictional narratives the rabbis contemplated the relationship between God and Israel, attempting to make sense of God’s actions and Israel’s situation. “Beyond all else,” says David Stern, a renowned scholar on rabbinic parables, “the mashal [parable] represents the greatest effort to imagine God in all Rabbinic literature.”[27] Typically, the parables are ambiguous, suggesting ideas rather than presenting clear-cut answers.

A parable, or mashal in Hebrew, usually consists of two parts: a short fictional narrative introduced with the phrase “This may be compared to,” followed by a nimshal, the situation that the parable attempts to illustrate, typically introduced with the word “thus” or “similarly.” The nimshal is possibly a secondary feature, a replacement for the real-life situation in which the parable was originally told (the way in which the Gospels generally depict the parables of Jesus), added when the parable was later transmitted orally or committed to writing. In the exegetical settings where most rabbinic parables appear, the nimshal gives the audience the information required in order to understand the parable.

The mashal and nimshal interact and together form a message. Most rabbinic parables contain a point of discontinuity—an unexpected, unexplained, or peculiar element, something that violates the audience’s expectations as to human behavior, either in the psychological, social, or religious realm—and in this irregularity the key to the parable’s message should be sought. Such points of discontinuity may be a missing link in a series of events, a missing cause or motive for a character’s action, a failure to offer reasonable explanations for an occurrence in the story, a contradiction in the text that challenges the audience’s understanding of the story, an unexplained departure from accepted norms, or a discrepancy between the mashal and the nimshal.

In the majority of parables, God is portrayed as a king and Israel as his wife, son or servant. This pertains even though many of these parables have nothing intrinsically royal about them; it is the result of a stereotyping of parables, assimilating them to the literary form of a king-mashal. Through this process, an anonymous man or father would be transformed into a king without any change to the parable’s plot or meaning. The king in the king-mashal is modeled upon the Roman emperor or his procurator or proconsul in the land of Israel, and although the parables are fictional narratives constructed to shed light on a biblical verse, they nevertheless reflect the realities of everyday life of their authors/redactors in the land of Israel.

Since the parables focus on the relationship to God, it is not surprising that the only character in the parable to consistently possess a personality is the king. All other figures are stock characters with little psychological or emotional depth whose behavior is usually predictable or easily explained. The choice of motif for each parable is important for the message, however, since they highlight different aspects of the relationship between God and Israel. For instance, the relationship between a man and his wife is different from that between a man and his son or between a man and his servant, thus making the choice of motif integral to the message of the parable.[28]

Below is a parable from Lamentations Rabbah, illustrating some of these features. Lamentations Rabbah, redacted in the fifth century, is largely preoccupied with the destruction of the temple, applying the complaints and laments over the destruction of the first temple in the book of Lamentations to the destruction of the second temple. The book of Lamentations is still read on the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av, in commemoration of the destruction of both the first and the second temples. Understood as a punishment for Israel’s sins, it seems way out of proportion to those sins, this parable seems to claim. The people of Israel have tried to the best of their ability to observe the Torah, and God’s treatment of them can be compared to an unpredictable king who treats his wife unfairly.

[When they heard how I was sighing, there was none to comfort me; all my foes heard of my plight and exulted.] For You have done it [Lam. 1:21]. Rabbi Levi said: It is like a consort to whom the king said: Do not lend anything to your neighbors, and do not borrow anything from them. One time the king became angry at her and drove her out of the palace. She went about to all her neighbors, but none of them received her, so she returned to the palace. The king said to her: “You have acted impudently.” She said to him: “You are the one who has done it! Because you told me: Do not lend anything to your neighbors, and do not borrow anything from them. If I had lent them an article or borrowed one from them, and if one of them had seen me outside of her home, would she not have received me?” Similarly at the time [following the destruction], the gentile nations went everywhere the Israelites fled and blocked them [from fleeing]: in the east, in the west, in the north, and in the south . . . The Holy One, blessed be He, said to Israel: You have acted impudently! Israel said before the Holy One, blessed be He: “But have You not done it?! For You told us: You shall not intermarry with them: do not give your daughters to their sons or take their daughters for your sons [Deut. 7:3]. If we had married our daughters to their sons, or taken their daughters for our sons, and one of them had seen their daughter or their son with us, would they not have received us?” That is [the meaning of], For You have done it.[29]

The king, of course, represents God, his wife Israel, and the prohibition of lending to and borrowing from the neighbors stands for the prohibition for Israel to intermarry with her non-Jewish neighbors. When told in the parable form, however, this prohibition as well as the king’s behavior is decidedly odd. For no good reason he prohibits his wife from interacting with their neighbors, thus violating regular accepted norms. Husbands do not usually prohibit their wives from borrowing or lending things from the neighbors; on the contrary, there is a halakhic tradition saying that a wife whose husband does so has the right to ask for a divorce, since such a prohibition will cause her to be disliked by her neighbors:

If a man places his wife under a vow not to lend or not to borrow a sieve, a basket, a millstone, or an oven, he must divorce her and give her ketubah to her because he causes her to have a bad name among her neighbors.[30]

The king’s unpredictable nature is further emphasized by his sudden anger and decision to drive his wife from the palace. Since no reason is given for these actions either, he appears cruel and despotic. His wife has obviously not defied his prohibition—evident from the fact that the neighbors refuse to take her in—so disobedience on her part cannot be the reason for his anger. The king bans her from the palace, but does not divorce her, thus placing her in a very difficult situation. He seemingly does not want to have anything to do with her, but she is still bound by marriage to him, dependent on him, and cannot remarry. There is a complete breakdown in communication; she does not understand what he wants from her and he makes no attempt to explain or talk to her at all. The parable is told from the wife’s perspective, making the audience sympathize with her.

In this parable, the interpreters grapple with God’s seemingly unfair and cruel treatment of Israel. In the parable, the wife’s predicament is the direct result of her faithful obedience to the king’s unreasonable decrees, and similarly, the narrative seems to say, Israel is now exiled and pursued by enemies precisely because she has obeyed the Torah’s laws. Indeed, God acts contrary to his own laws when he prohibits Israel to intermarry with her neighbors, condemning her to isolation and persecution. Although the laws in the Torah cannot strictly speaking be against the law since they are the law, God nevertheless appears to act against the spirit of his own law, if not against the letter. “For you have done it!” Israel laments, decontextualizing the biblical verse and transforming it into an angry accusation of God’s tyrannical actions. Accordingly, the parable’s message appears to be clear: God has behaved with obvious injustice toward Israel. He has acted against the spirit of his own law, and all the while Israel has faithfully obeyed his law, and suffered precisely on account of her faithful obedience.[31]

However, a peculiar detail in the parable may hint at a somewhat different understanding or at least a double meaning. The complete lack of understanding and communication between the king and his wife is somewhat odd and surely not the norm in a marriage. If applied to the relationship between God and Israel, it could be taken to indicate a total breakdown in communication between God and Israel and a lack of understanding between them, causing Israel to misinterpret God’s actions. The common understanding of the destruction of the temple and the exile is that they are a punishment for Israel’s sins, but as such they appear unjust, or at least vastly out of proportion. However, if this is a misinterpretation of God’s actions, and if the destruction of the temple and the exile are not a punishment but rather the inevitable outcome of living in a covenantal relationship with the God of Israel, the entire situation changes. By portraying the king and his wife as being bound to one another in such an abnormal relationship, the author of the parable may hint that rather than being understood as a punishment, Israel’s misfortunes is a consequence of being singled out as God’s people. Her difficulties can be understood as a test that she fails, but not because of any disobedience on her part but simply because she does not understand that being God’s people means isolation and occasionally persecution from the non-Jewish peoples around her. If this is the case, God is surely to blame because he has not made any attempt to communicate with Israel and explain to her the reason for her misfortunes, but Israel shares a little of the blame too for accusing God of injustice rather than attempting to understand him and the nature of their relationship.[32]

Midrash and Rabbinic Law

After having discussed interpretation of non-legal (aggadic) texts, we will now turn to interpretation of legal (halakhic) ones. As with interpretation of aggadic texts, legal exegesis also takes as its point of departure irregularities in the biblical text, such as contradictions, unnecessary words, or repetitions.

In the example below, the well-known Jewish custom not to mix meat and milk is presented as a result of interpretation of Exod. 23:19, “You shall not boil a kid it its mother’s milk”:

Abba Hanin said in the name of R. Eliezer: Why is this law stated in three places? [Exod. 23:19, 34:26; Deut. 14:21]. Once to apply to large cattle, once to apply to goats, and once to apply to sheep . . . R. Shimon ben Yohai says: Why is this law stated in three places? One is a prohibition against eating it [milk and meat together], one is a prohibition against deriving any benefit from it, and one is a prohibition against the mere cooking of it [milk and meat together].[33]

Based on the multiple occurrences of the injunction to boil a kid in its mother’s milk, Abba Hanin extends the prohibition to include cooking other animals’ offspring in their mothers’ milk too. Based on the same repetition of the verse, R. Shimon ben Yohai extends the prohibition from cooking milk and meat together to eating it and deriving benefit from it, for instance, by selling meat and milk cooked together. According to this text, the custom of not mixing meat and milk originated in a rabbinic attempt to make sense of the repetition of the prohibition to boil a kid in its mother’s milk, but one cannot help but wonder whether this exegesis rather serves to anchor an already existing custom in the biblical text.[34]

By contrast, other laws are not presented as being the result of exegesis, but simply seem to rest on rabbinic authority. Such is, for instance, the case with the laws of the Sabbath as stated in the Mishnah where the meaning of the word “work” is defined as encompassing thirty-nine categories of activities with no references to the biblical text (m. Shabb. 7:2). The fact that the Mishnah merely lists the different kinds of work forbidden on the Sabbath with no references to biblical verses suggests that the development of these prohibitions occurred independently of the biblical text. Although the Talmud (b. Shabb. 49b) links them to biblical passages by making a point of the fact that two occurrences of the Sabbath commandment (Exod. 31:12-17 and 35:1-3) are directly connected to the description of the building of the Tabernacle in the desert, and thus concludes that “work” includes all activities connected to the building of the Tabernacle, this seems to be a later development.[35]

Thus, there are two ways in which rabbinic laws are preserved: independently of biblical verses as in the Mishnah, and in connection with biblical verses as in midrash. In the case of the Mishnah, the laws are based on rabbinic authority rather than on the Bible, whereas in the case of midrash it is the fact that they are derived from the Bible that gives them authority. It also seems that laws originated in these two ways: as extra-textual traditions on the one hand and as a consequence of biblical interpretation on the other. Which one of these is the main source of rabbinic laws is a hotly debated issue among scholars and it recalls the scholarly debate on how much of rabbinic expansions derives from exegesis of the biblical text and how much is generated by outside non-textual concerns, such as ideology and theology, in the case of non-legal texts. In the case of rabbinic law, scholars take similar positions, some arguing that most laws originated as extra-biblical traditions that were only later connected to a biblical verse in order to anchor an already existing custom in the Bible, while others maintain that rabbinic laws were primarily derived through exegesis of the biblical text. Yet others suggest that that the methods coexisted, perhaps represented by different schools.[36]

Given the interaction between the biblical text and ideological assumptions of the rabbinic reader in the production of midrash aggadah, it appears likely that a similar process was at work in the realm of halakhah, so that rabbinic laws developed both as a result of an understanding of the biblical text and independently of it in response to outside concerns. The claim that the two methods were contemporary and existed side by side has received support in the recent scholarship of Azzan Yadin, who has argued that the fact that tannaitic literature contains two distinct approaches to rabbinic law, one giving priority to midrash and the other to traditions independent of the biblical text, indicates that these two approaches were contemporary and represented by different schools.[37]

Thus, common to all ancient Jewish biblical interpretation, whether applied to legal or non-legal texts, is a set of particular assumptions about the biblical text and a non-contextual approach. Verses are typically interpreted without any regard for the biblical context in which they appear and any verse is considered able to illuminate any other verse. This mode of interpretation continued until the medieval period when it gave way to a more context-oriented approach as a consequence of a shift in assumptions about the biblical text.

Collections of Midrash

Rabbinic biblical interpretations were transmitted orally over a long period of time before they were compiled and written down. They were eventually collected into compilations, which include many different, sometimes contradictory interpretations that are placed side by side. The earliest collections of midrash consist of Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael and Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai to Exodus, Sifra to Leviticus, Sifre to Numbers, and Sifre to Deuteronomy. The main bulk of their content dates from the tannaitic period but they were probably redacted at the beginning of the amoraic period.

The tannaitic midrashim fall into two groups based on differences concerning rabbis cited, interpretive terminology and characteristic hermeneutic practices. These two groups have for a long time been associated with the schools of Rabbi Aqiva and Rabbi Ishmael respectively and, as Yadin has recently demonstrated, these differences remain irrespective of whether they can be traced back to the historic figures of Rabbi Aqiva and Rabbi Ishmael. Accordingly, the terms “Rabbi Ishmael midrashim” and “Rabbi Aqiva midrashim” function as a shorthand for a set of distinct and recognizable interpretive practices, assumptions, and terms that appear in the halakhic sections of the tannaitic collections of midrash.

The group of midrashim associated with the school of Rabbi Ishmael is made up of Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael (to Exodus) and Sifre (to Numbers), while Sifra (to Leviticus) and Sifre (to Deuteronomy) make up the subgroup associated with Rabbi Aqiva. According to this division, the less known Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai would be the Rabbi Aqiva school counterpart to the better known Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. The Rabbi Ishmael midrashim generally show a greater interpretive restraint than the Rabbi Aqiva midrashim and seem to consider only particular kinds of textual irregularities to be legitimate targets for interpretation. They also take into consideration the broader biblical context and do not seem to subscribe to the idea that scriptural verses can bear multiple interpretations. Of these, the approach associated with Rabbi Aqiva, according to which every letter of the biblical text can be subject to interpretation, has become the one generally associated with midrash since it is the one that has influenced all subsequent rabbinic literature.[38]

Tannaitic midrashim

| School of R. Ishmael | School of R. Aqiva | |

| Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael | Exodus | Mekhilta de-Rabbi |

| Shimon bar Yohai | ||

| Leviticus | Sifra | |

| Sifre (to Numbers) | Numbers | |

| Deuteronomy |

Sifre (to Deuteronomy) |

The compilations of midrash from the amoraic and post-amoraic periods are numerous, and space permits only the most important ones to be mentioned here.[39] The classic compilations of midrash from the amoraic period include Genesis, Leviticus, and Lamentations Rabbah and Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana, likely compiled during the fifth century, Genesis Rabbah first and the others somewhat later. Genesis Rabbah and Lamentations Rabbah are verse-by-verse commentaries belonging to the group known as exegetical midrashim. Leviticus Rabbah and Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana belong to the group known as homiletical midrashim because they are believed to have originated as sermons for the Sabbath or other holy days. They take as their point of departure some of the verses (usually the first) of the weekly portion read in the synagogue and develop a sermon based on them.

Midrash Tanhuma is a homiletic midrash to the Pentateuch that exists in two different textual recensions, one known simply as the printed version and the other as the Buber version since it was published by Salomon Buber. The two versions differ greatly in their commentaries on Genesis and Exodus, but are very similar in their comments on the three remaining parts of the Pentateuch. Buber’s version probably represents an Ashkenazi (northern European) tradition. While some scholars date Midrash Tanhuma to the first half of the ninth century, others date the main bulk of the contents to the fifth century, with reservation for possible later additions. Some of the material in Midrash Tanhuma is also found in the midrashim known as Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy Rabbah, collections consisting of different sources with various origins dating from the mid-fifth to the twelfth century.

Amoraic and Post-Amoraic Midrashim

| Genesis Rabbah | early 5th century |

| Lamentations Rabbah | early 5th century |

| Leviticus Rabbah | mid 5th century |

| Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana | 5th century |

| Midrash Tanhuma | 5th century with later additions |

| Deuteronomy Rabbah | 5th-9th century |

| Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer | 8th-9th century |

| Numbers Rabbah | 9th-11th century |

| Exodus Rabbah | 10th-12th century |

Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer is a paraphrase of parts of the Bible, a genre known as “rewritten Bible.” It is the only midrash, with the exception of some medieval commentaries, that seems to have been written by a single author and is usually dated to the eighth or ninth century. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, anthologies were published that included all commentaries known to the compilers, the best known being Midrash ha-Gadol and Yalqut Shimoni.

Targums

In its broad sense of biblical interpretation, midrash also includes the Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible, known as targums. The Hebrew word targum simply means “translation” in general, but the term is used exclusively to denote the translation of the Bible into Aramaic. Far from being literal translations, however, the targums include interpretive traditions, some of which are known from the rabbinic collections of midrash while others are unique to the targums. The original Sitz im Leben of the targums is most likely the synagogue, where the weekly readings from the Torah and the Prophets were read first in Hebrew and simultaneously translated into Aramaic by a translator (meturgeman). According to the Mishnah and Tosefta, the reader would recite a verse from the Torah, after which the translator would render the same verse in Aramaic, followed immediately by the reader’s recitation of the next verse in Hebrew. In case of the Prophets, three verses at a time were read and translated in this fashion. The sources emphasize that the reading and translation be conducted in such a way that the two voices, that of the reader and that of the translator, be clearly distinguishable from each other.[40]

Until recently, it was assumed that the Bible was translated into Aramaic because the Aramaic-speaking masses of Jewish people in the land of Israel no longer understood biblical Hebrew, but lately a number of arguments against this view have been raised. Contrary to the earlier scholarly consensus that held that Hebrew had ceased to be a spoken language in the post-Bar Kokhba period, synagogue inscriptions from the Galilee suggest a multilingual milieu where people understood both Hebrew and Aramaic and to a certain extent even Greek. A reexamination of rabbinic sources has likewise led to the conclusion that the targums were intended for an audience that was familiar with both Hebrew and Aramaic and could easily switch between them.

Targums

| Pentateuch | |

| Onqelos | 3rd century |

| Neofiti | 4th-7th centuries |

| Pseudo-Jonathan | 7th-8th centuries |

| Prophets | |

| Jonathan ben Uzziel | 3rd century |

These circumstances, together with the fact that the targums never replaced the reading of the Torah in Hebrew the way that the Greek translation, the Septuagint, did for Greek-speaking Jews, have led Steven Fraade to suggest that the primary function of the targums was to convey to the synagogue audience a correct, that is, a rabbinic, interpretation of the Bible. The simultaneous rendering of the Torah-reading into Aramaic is understood to mediate the content of the Torah-reading and is in some rabbinic sources from the amoraic period compared to what was perceived to have happened at Sinai. Just as God’s word was mediated through Moses, the public reading of the Torah in the synagogue is mediated through a translator who is both a bridge and a buffer between the written Torah and its oral reception and interpretation (y. Meg. 4:1).

In light of other rabbinic texts, which describe the revelation at Sinai as God speaking in several languages although the Torah was recorded only in Hebrew,[41] the public reading and translation of the Torah in the synagogue may have been perceived as a reenactment of the revelation at Sinai. The rabbis seem to have felt that to comprehend fully the meaning of the Hebrew text of the Torah, the written Torah must be translated into the seventy (that is, the totality) languages in which it was originally heard by Israel. Thus, a translation is in itself a form of explication, also for those who understood the original Hebrew. Although translation/interpretation was considered an integral part of the Torah-reading, the rabbis were also anxious to distinguish between the two. The targum had the advantage of permitting the rabbis to incorporate rabbinic interpretation into the Bible itself, but it also meant that people might confuse the interpretation with the written Torah. In order both to safeguard the written Torah and ensure the flexibility of the interpretation, the rabbis wished to keep the two distinct from one another, and this, argues Fraade, may have been one reason why the interpretation appears in Aramaic. The choice of Aramaic as the voice of interpretive paraphrase clearly distinguishes it from that of the written Torah and allows the two to be heard as distinct voices. In order to illustrate the relationship between the two, Fraade employs a musical metaphor comparing the reader and the translator to a soloist and an accompanist. Just as the musical accompanist enhances the performance of the soloist, so the targum contributes to the understanding of the written Torah, but in both cases the accompanist must not draw attention away from the principal performer. It is for this reason that the accompanist performs on a different instrument, and for the translator of the Torah-reading this different instrument was Aramaic.[42]

The best-known targums are Onqelos, Pseudo-Jonathan, Neofiti, and the Fragmentary Targum to the Pentateuch along with Targum Jonathan ben Uzziel to the Prophets. Targum Onqelos and Targum Jonathan to the Prophets were likely compiled in Babylonia during the third century, but at least Onqelos originally seems to be from the land of Israel. It is believed to have originated during the first half of the second century, and brought to Babylonia after the Bar Kokhba uprising, where it was redacted in the third century.

Neofiti, Pseudo-Jonathan, and the Fragmentary Targum were in use in the land of Israel and were collectively known as the Palestinian targum. They do not appear to have become standardized, and accordingly continued to develop during a long period of time, making it very difficult to date them. Neofiti is commonly dated to a period between the fourth and seventh centuries while Pseudo-Jonathan was probably compiled as late as the seventh or eighth century, even though it contains materials that are much older. The Fragmentary Targum consists of comments to scattered verses or words and never seems to have been a complete targum. In spite of intense scholarly debate, no consensus about its origin has been reached. Some scholars believe that it originated as an addition to Onqelos, while others maintain that it is a variant reading of Pseudo-Jonathan.

While Onqelos is a relatively literal translation, the Palestinian targumim are considerably more verbose. Pseudo-Jonathan has the most extensive additions, being approximately twice as long as the Hebrew text. There are also targums to the Writings (the last part of the Hebrew Bible), of which some are rather literal and others more expansive.[43] In order to illustrate similarities and differences between rabbinic compilations of midrash and the targums, we will presently have a look at the expansion of Gen. 4:8 from Targum Pseudo-Jonathan. The biblical text is italicized, and the remaining text consists of interpretation.

Cain said to his brother Abel: “Come, let us both go outside.” When the two of them had gone outside Cain spoke up and said to Abel: “I see that the world was created with mercy, but it is not governed according to the fruit of good deeds, and there is partiality in judgment. Therefore your offering was accepted with favor, but my offering was not accepted from me with favor.” Abel answered and said to Cain: “The world was created with mercy, it is governed according to the fruit of good deeds, and there is no partiality in judgment. Because the fruit of my deeds was better than yours and more prompt than yours my offering was accepted with favor.” Cain answered and said to Abel: “There is no judgment, there is no judge, there is no other world, there is no gift of good reward for the righteous, and no punishment for the wicked.” Abel answered and said to Cain: “There is judgment, there is a judge, there is another world, there is the gift of good reward for the righteous, and there is punishment for the wicked.” Concerning these matters they were quarreling in the open country. And Cain rose up against Abel his brother and drove a stone into his forehead and killed him.

This expansion obviously reflects the same basic problem in Genesis 4 that the midrashim we have encountered attempted to resolve, namely, that God appears arbitrary and even unjust in his acceptance of Abel’s sacrifice and rejection of Cain’s. The form, however, is different. Instead of quoting the biblical verse and then commenting on it, the targum weaves the biblical verse and its interpretation together so that it is not immediately clear where the one ends and the other starts. The idea that the reason for the murder was a quarrel between the brothers is familiar to us from Genesis Rabbah (22.7), and the content of their argument seems to summarize ideas known from other sources. Abel embodies the “correct” rabbinic view of the world and God and argues that his sacrifice was indeed superior to Cain’s (cf. Gen. Rab. 22.5), while Cain’s claims reflect rabbinic doubts as to God’s justice, also reflected—albeit less boldly—in other rabbinic sources.[44]

The Binding of Isaac—Theology and Biblical Interpretation

To conclude the discussion of rabbinic biblical interpretation and to illustrate the interwoven nature of rabbinic exegesis and theology, we will now turn to a sample of rabbinic interpretations of the well-known story of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac in Genesis 22, known in Jewish tradition as the aqedah (“binding” [of Isaac]).[45]

Isaac—A Willing Sacrifice

As briefly mentioned above, most rabbinic interpretations make Isaac the principle character of the story. According to the aforementioned expansion from Genesis Rabbah, it is Isaac himself who, in a dispute with his brother Ishmael, provokes God’s command to Abraham to offer him as a sacrifice, providing him with the opportunity to demonstrate his complete obedience and loyalty to God. A similar tradition appears in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, but here the argument concerns not only whom God loves the most, but also who is Abraham’s rightful heir:

After these words [Gen. 22:1], after Isaac and Ishmael had quarreled, Ishmael said: “It is right that I should be my father’s heir, since I am his first-born son.” But Isaac said: “It is right that I should be my father’s heir, because I am the son of Sarah his wife, while you are the son of Hagar, my mother’s maidservant.” Ishmael answered and said: “I am more worthy than you, because I was circumcised at the age of thirteen, and if I had wished to refuse, I would not have handed myself over to be circumcised. But you were circumcised at the age of eight days. If you had been aware, perhaps you would not have handed yourself over to be circumcised.” Isaac answered and said: “Behold, today I am thirty-seven years old, and if the Holy One, blessed be He, were to ask all my members I would not refuse.” These words were immediately heard before the Lord of the world, and at once the Memra of the Lord[46] tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!”

After the emergence of Islam, Ishmael was often identified with the Arabs, and it is possible that Pseudo-Jonathan’s version of the argument between Isaac and Ishmael is a later tradition reflecting polemics against Islam. Isaac (the Jews) and Ishmael (the Arabs) are both descendants of Abraham, and Ishmael’s descendants could with some justification claim to be God’s people as well. Since the kinship with Abraham does not indisputably settle the issue to Isaac’s advantage, their dispute will instead be settled by their dedication to God.[47]

More importantly, this expansion clearly articulates the idea, present in practically all rabbinic interpretations, that Isaac was an adult at the time rather than a young boy. The number thirty-seven is arrived at by relating chronologically a number of events, assuming as the rabbis did that there was a significance to the order in which biblical events were told. The beginning of chapter 23 informs us of Sarah’s death at the age of 127 years, and from the fact that this piece of information appears directly in connection with the events related in chapter 22, the rabbis deduced that these events were somehow related, and accordingly concluded that Sarah died because she was told that Isaac had actually died. Since we know from Gen. 17:17 that Sarah was ninety years old when Isaac was born, Isaac must have been thirty-seven at the time Abraham received the command to offer him as a sacrifice. Although the exact age varies somewhat, targums and rabbinic sources all agree that Isaac was a grown-up man.[48] Josephus sets his age at twenty-five (A.J. 1. 227), so the idea that Isaac was an adult obviously predates the rabbinic period.

The implication of the assertion that Isaac was an adult is that he went willingly and knowingly to be offered as a sacrifice. An old man, as Abraham was at the time, could not bind a young man on the altar without his consent. According to the rabbis, Abraham even hinted to Isaac in Gen. 22:7-8, the only conversation taking place between father and son, that he was the lamb intended to be offered as a sacrifice. Genesis 22:8 reads: “And Abraham said, ‘God will see to the sheep for His burnt offering, my son,’” and by placing the comma differently the rabbis made Abraham say: “God will see to the sheep, a burnt offering are you, my son,” thus revealing to Isaac that he was the intended sacrifice.

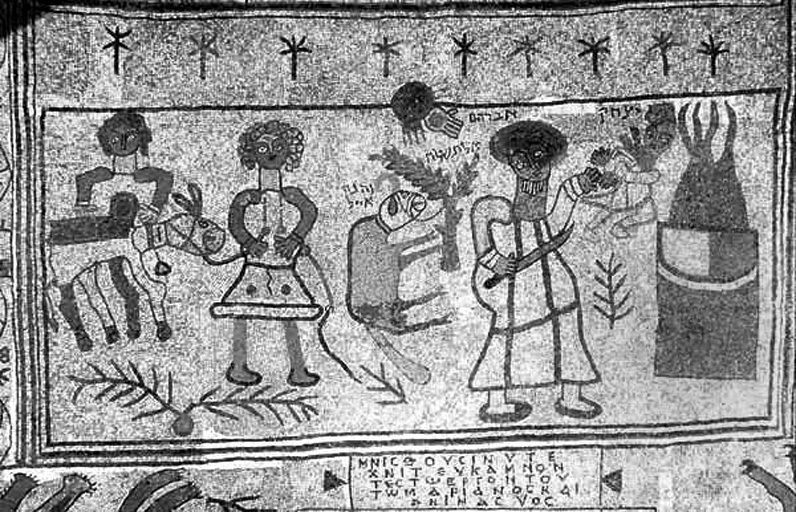

Fig. 6. The Aqedah as depicted on the mosaic floor of the Bet Alpha Synagogue in the Galilee. Photograph in the public domain.

Seeing in their own interpretations only an explicit expression of what was implicit in the biblical text, they believed that God had deliberately placed in the text hints to the effect that Isaac was an adult who was knowingly and willingly letting himself be offered on the altar, and all they did was to explicitly express what God had intended. One such hint, they believed, was the repetition of the phrase “the two of them walked together,” appearing in both verse 6 and verse 8. Since the Bible, according to rabbinic assumptions, does not contain any repetitions or superfluous information, the second occurrence of the phrase must necessarily add some new information, and since the verse between them relates the conversation between Abraham and Isaac, the rabbis understood this to mean that Abraham in that conversation disclosed to Isaac that he was to be sacrificed. As a sign that Isaac now knows and willingly accepts his fate, the text in verse 8 reiterates that “the two of them walked together.” When the phrase occurs the first time, Isaac does not know what lies in wait for him, in verse 7 he is told, and then the phrase is repeated in verse 8 to affirm that in spite of this knowledge, he continues to walk with his father, willingly accepting his fate. Tg. Pseudo-Jonathan as well as the other Palestinian targums translate the Hebrew yahdav as “together,” and then add the explanatory words, “with a perfect heart,” to emphasize that Isaac agreed with his father. The targums and rabbinic sources are all anxious to point out that Abraham and Isaac were in perfect agreement concerning the sacrifice and that Isaac was not merely a passive victim.[49]

The idea that Isaac willingly agreed to give up his life in obedience to the divine decree did not originate with the rabbis, as is evident from the fact that the idea appears in a number of pre-rabbinic sources. Josephus, Philo, and 4 Maccabees all maintain that Isaac’s near-death was self-conscious and freely chosen, and according to Biblical Antiquities, a work erroneously attributed to Philo, preserved in Latin but probably composed in Hebrew sometime in the first century, Abraham reveals to Isaac that he is about to offer him as a burnt offering as soon as they set out on the journey. To this Isaac answers: “Yet have I not been born into the world to be offered as a sacrifice to him who made me?”[50]First Clement, one of the earliest Christian writings outside of the New Testament dating from the late first or early second century, likewise states that Isaac, knowing full well what was to happen, was willingly led forth to be sacrificed (1 Clem. 31:4).

Thus, the idea of Isaac’s voluntary participation in the aqedah predates the rabbinic period but was taken up by the rabbis and further developed by them. Sifre, the tannaitic midrash to Deuteronomy, says that “Isaac bound himself to the altar,”[51] and according to the targums, Isaac asks his father to tie him carefully to the altar, in case he should become frightened and injure himself while struggling to become free, thus rendering the sacrifice invalid.[52] Isaac’s readiness to give up his life is further emphasized in the targumic addition to Gen 22:10, saying: “Come, see two unique ones who are in the world; one is slaughtering, and one is being slaughtered; the one who slaughters does not hesitate, and the one who is being slaughtered stretches forth his neck.”[53]

Isaac’s “Death” Atones for Israel

A number of targumic and rabbinic sources assert that Isaac’s death, or near-death, has an atoning effect, and the idea that God will remember the binding of Isaac and on account thereof forgive the sins of Israel is widespread in rabbinic tradition. On the Day of Judgment, according to one tradition, God will show mercy on account of the binding of Isaac: “[W] hen the children of Israel give way to transgressions and evil deeds, remember for their sake the binding of their father Isaac and rise from the throne of Judgment and sit on the throne of Mercy, and being filled with compassion for them have mercy upon them and change for them the Attribute of Justice into the Attribute of Mercy! When? In the seventh month [on the first day of the month]” [Lev. 23:24].[54]

A similar targumic tradition says that just as Abraham is about to slaughter Isaac, he prays that God may remember his willingness to sacrifice Isaac and for his sake save Israel’s descendants in the future:

And Abraham worshiped and prayed in the name of the Memra of the Lord and said: “I beseech by the mercy that is before you O Lord—everything is manifest and known before you—that there was no division in my heart the first time that you said to me to offer my son Isaac, to make him dust and ashes before you; but I immediately arose early in the morning and diligently put your words into practice with gladness and fulfilled your decree. And now, when his sons are in the hour of distress you shall remember the Binding of their father Isaac, and listen to the voice of their supplications, and answer them and deliver them from all distress, so that the generations to arise after him may say: ‘On the mountain of the sanctuary of the Lord Abraham sacrificed his son Isaac, and on this mountain the glory of the Shekhinah[55] of the Lord was revealed to him.’”[56]

Here Abraham’s obedience to God and his refusal to spare his son has become the cause and condition for future deliverance of his descendants. When God announces his decision to destroy Israel after the sin of the Golden Calf (Exod. 32), Moses asks him to spare them appealing to Isaac’s sacrifice: “[R]emember their father Isaac who stretched forth his neck on the altar ready to be slaughtered for your name, and let his death take the place of the death of his children.”[57] The idea that a martyr’s death has the power to atone for the sins of others and rescue them is a development of a pre-rabbinic theme present already in 4 Maccabees: “Through the blood of these righteous ones and through the propitiation of their death the divine providence rescued Israel, which had been shamefully treated.”[58]

In the Mekhilta, an early commentary on Exod. 12:13 in which God commands the Israelites to smear blood from the slaughtered paschal lamb on their doorposts so that he will know where they live and spare them when he strikes the Egyptians with the last plague, Isaac takes the place of the paschal lamb and the Israelites are saved on account of the binding of Isaac: “And the blood on the houses where you are staying shall be a sign for you: when I see the blood I will pass over you, so that no plague will destroy you when I strike the land of Egypt [Exod. 12:13]. [W]hen I see the blood [Exod. 12:13], I see the blood of the binding of Isaac.”[59] In the blood from the paschal lamb on the Israelites’ doorposts, God sees the blood of the sacrifice of Isaac and on his account the Israelites are saved from the last plague and redeemed from slavery. In Genesis 22, Isaac was at the last moment replaced by a ram that was offered in his place, but here we have come full circle and Isaac takes the place of the paschal lamb.

The identification of Isaac with the paschal lamb first appears in Jubilees, dated to the middle of the second century B.C.E., albeit it is only implicit there. According to Jubilees, God’s command to Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice occurred “in the seventh week, in its first year, in the first month, in that jubilee, on the twelfth of that month” (Jub. 17:15). The month in which Passover is celebrated is the first month of the year, according to Exod. 12:2, and the twelfth day of the first month is three days before the paschal lamb is to be offered, which occurs at twilight of the fourteenth (Exod. 12:6; Lev. 23:5). Since the journey to the designated place took Abraham three days (Gen. 22:4; Jub. 18:3), the binding of Isaac would coincide with the offering of the paschal lamb on the evening of the fourteenth. This assumption makes the aqedah a foundation story for Passover, an interpretation made explicit in the conclusion of Jubilee’s retelling of Genesis 22: “And he [Abraham] observed this festival every year for seven days with rejoicing. And he named it ‘the feast of the Lord’ according to the seven days during which he went and returned in peace” (Jub.18:17). The only seven-day festival in the first month is, of course, Passover (Lev. 23:5-8), and Jubilees seems to derive its duration, for which the Bible gives no reason, from Abraham’s journey—three days to the land of Moriah, three to return, and one day (the Sabbath) without travel. In this interpretation, Passover is celebrated in commemoration of Abraham’s refusal to spare his own son when God commanded that he be sacrificed, and by founding the story of Passover upon the aqedah, Jubilees makes a father’s willingness to give up his son a key component of Israel’s redemption from Egypt.

It is this line of thought that is further developed in the Mekhilta text above, in which the aqedah (and the Passover sacrifice) has become the foundation for Israel’s rescue from affliction throughout history. This idea is even more clearly expressed in a passage in Exodus Rabbah where it is said that Isaac was “born and bound” in the month of Nisan, the month in which “Israel was redeemed from Egypt and in which they will be redeemed in the future,” reflecting a view of the aqedah as an archetype of redemption and a foreshadowing of the eschatological deliverance, envisioned as a new Exodus.[60]

This is an amazing development in which the original story of a father who is explicitly forbidden to hurt his son (Gen. 22:12) is transformed into one in which he wounds, spills his blood, or even kills the son. “When I see the blood I will pass over you,” God tells the Israelites enslaved in Egypt, but the Mekhilta interprets this to mean that God saw the blood of Isaac. The idea that some of Isaac’s blood was indeed spilled is present in a number of rabbinic sources,[61] and actually appears already in the above mentioned first century work Biblical Antiquities: “And he [Abraham] brought him [Isaac] to be placed on the altar, but I gave him back to his father and, because he did not refuse, his offering was acceptable before me, and on account of his blood I chose them.”[62] According to this source, God made Israel his people on account of Abraham’s willingness to offer Isaac and Isaac’s readiness to be sacrificed. Thus, the very existence of their descendants is dependent on this act.