3

The European Spring

VISIONS OF THE MACHINE AGE

On her visits to England during the 1830s the writer and revolutionary Flora Tristan (1803–44) was shocked by the condition of the factory workers she encountered:

Since I have known the English proletariat, I no longer think that slavery is the greatest human misfortune: the slave is sure of his bread all his life, and of care when he is sick; whereas there exists no bond between the worker and the English master. If the latter has no work to give out, the worker dies of hunger; if he is sick, he succumbs, on the straw of his pallet . . . If he grows old, or is crippled as the result of an accident, he is fired, and he turns to begging furtively for fear of being arrested.

For women, unemployment meant a fate even more diabolical, Flora noted, as she observed the prostitutes crowding the pavements along Waterloo Road. ‘In London,’ she wrote, ‘all classes are badly corrupted.’ To try and find out something of the system of government that presided over these horrors, she shocked a Tory Member of Parliament by asking him to lend her his clothes so she could sit in the public gallery (women were not admitted). Eventually she gained admission dressed as a young Turk; though this fooled nobody, the custodians let her in anyway. She listened to a speech by the Duke of Wellington (‘cold, tame, drawling’) but found no enlightenment. The machinery of the new factories impressed her, but she found the damage they inflicted on human beings appalling.

Born on 7 April 1803 to a French mother and a Peruvian father who had met in Spain, where her mother had gone ‘to escape from the horrors of the revolution’, Flora Tristan led an eventful life between the old world and the new. Her father, a landowner and friend of Simón Bolívar who claimed to be a descendant of Montezuma, served in the Spanish Army but died in 1807, leaving his widow and small child in serious financial difficulties. Her mother had married him in a church ceremony, which was not recognized in France, where only civil ceremonies had legal validity, so Flora was technically illegitimate. Living in a poor part of Paris, she became a wage-labourer, colouring engravings for an artisan, André Chazal (1796–1860), who owned a workshop in Montmartre. He fell in love with her and in 1821 they married. She was seventeen, he twenty-four. The marriage was not a success. She found him boorish, uneducated and irresponsible, prone to gambling and always in debt. He thought she ‘gave herself airs’. In 1825, pregnant with their third child, she left the marital home, claiming her mother had forced her into a marriage that had been nothing but ‘endless torture’.

Divorce was illegal in France; as a wife, Flora was a legal minor, with no rights and no property. In 1828, Chazal agreed to a legal separation of their property. Three years later, he began to look for her with the aim of getting back his children – two boys and a girl, Aline, – over whom he had by law the sole right of guardianship. While Flora went to Peru to try and recover her family property, Chazal tracked down Aline at a boarding school and kidnapped her. He began publishing defamatory pamphlets about Flora. ‘She possesses none of the virtues which bring esteem to the daughter, the wife, the kinswoman or the woman of quality,’ he complained: ‘For her, family ties, the duties of society, and the principles of religion, are useless impedimenta, from which she frees herself with an audacity which is fortunately quite rare.’ Ominously, he designed a gravestone for Flora, bought a pair of pistols, and started shooting practice. He became a regular in a wine bar opposite her apartment in Paris. On 10 September 1838 he spotted her walking along the street, approached her from behind, and shot her at point-blank range. The bullet entered the left side of her body, but failed to kill her. Doctors treated her, and she recovered, though the bullet was never removed. Chazal was arrested, found guilty of attempted murder, and sentenced to twenty years’ hard labour.

For Flora Tristan, the situation of a wife trapped in an unhappy marriage, like that of an operative in an English factory, was no better than that of a slave. In November 1837, in Peregrinations of a Pariah, she pilloried her husband, and told every woman trapped in an unhappy marriage: ‘Feel the weight of the chain which makes you his slave and see if . . . you can break it!’ She began to petition the Chamber of Deputies for the legalization of divorce. ‘Up to now,’ she wrote in 1843, ‘woman has counted for nothing in human society . . . The priest, the lawmaker, and the philosopher, have treated her as a true pariah. Woman (half of humanity) has been excluded from the Church, from the law, from society.’ Searching for ideas with which to justify her increasingly radical stance, Flora began to read the works of the Utopian socialists, mainly French writers such as Charles Fourier (1772–1837), who since the Revolution of 1789 had been attempting to sketch the contours of the ideal society. She was not impressed with what she found. ‘Many people,’ she wrote in 1836, ‘among whom I count myself, find the science of M. Fourier very obscure.’ Utopianism also ‘paralysed all action’ in the workers, she thought. She was frequently assisted by the compagnonnages on her travels through France, and came to be regarded by them as their ‘mother’, but her dismay at their internal divisions and quarrels was another spur to her to create a unified workers’ movement. ‘Divided,’ she told them, ‘you are weak, and you fall, crushed underfoot by all sorts of misery! Union creates power. You have numbers in your favour, and numbers mean a great deal.’

Her critics resented the very fact that she was challenging masculine supremacy through her melodramatic pronouncements and her assertive independence. Even more shocking was her advocacy of the communal upbringing of children and her acceptance of Fourier’s belief that permanent sexual relationships were contrary to human nature. Moreover, her appalling experience at the hands of her husband led her to reject relationships with men, and she took refuge in intimate friendships with other women, where power relations, she thought, would not be involved. Women, she declared, should have the vote, along with all adult men, as well as the right to work and education. The emancipation of women was closely bound up with the emancipation of the workers; both, in the end, would triumph together. She urged workers to declare the rights of woman, just as their fathers had declared the rights of man in 1791. Equal wages for equal work would follow if inequalities in power between men and women were done away with. This would only be a recognition of the fact that ‘in all the trades where skill and dexterity are required, the women do almost twice as much work as the men’. Flora did not live to see her ideas put into practice. She caught typhoid on a visit to Bordeaux in 1844 and she died on 14 November, aged just forty-one. Her memory was kept alive by the workers and resurfaced in 1848. Her daughter Aline married Clovis Gauguin, a republican journalist, in 1846, but he died en route to Peru three years later. Their son Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), who stayed with Aline in Peru for seven years, supported by her family, later became an artist whose own global peregrinations perhaps owed something to his upbringing in two continents.

For the most part, Flora Tristan was right to criticize the Utopians’ lack of realism. But this did not mean that they failed to think about how to translate their ideas into reality. Central to many of them was the belief that by establishing perfect human communities, they would show the way to the future, a way so rational and so harmonious that people everywhere would quickly choose to go down it. Charles Fourier, for instance, proposed in his tract The New Industrial and Social World, published in 1829, the foundation of what he called phalansteries, or phalanxes, where around 1,600 people, men, women and children, would live a communal life based on shared social facilities. An architect, statistician and man of independent means, Fourier set up a community of this kind just outside Paris in 1832, though its inhabitants quickly quarrelled among themselves and departed increasingly from the ideas of its founder. His disciples eventually established communities in the United States. Perhaps inevitably, most of them only lasted a handful of years, or were transformed into more conventional settlements based on principles far removed from those of their founder.

Similar ideas were propounded by the lawyer and journalist Étienne Cabet (1788–1856), a man of humble origins who had taken part in the 1830 Revolution and served as an oppositional deputy in the early 1830s. More determinedly egalitarian than Fourier, he envisaged in his famous Voyage to Icaria (1840) a community where everyone worked equally and received the same rewards, everyone would have the vote, and all property would be held in common. This was ‘communism’, a word he invented. The downside of his Utopian prescription was that everyone would have to obey the community’s laws, and there would only be one newspaper, whose function was to express the common opinion of the community’s members. The desire for liberty, he warned, was ‘an error, a vice, a grave evil’ born of ‘violent hatred’. In 1848, despairing at ever being able to put his plans into operation in Europe, he sailed with a multinational group of followers, mostly artisans, to the United States, where they founded a number of Icarian communes. Most of them were short-lived. Their rules, which included a ban on smoking, were too strict for many of their members; even Cabet himself was expelled from one of them shortly before his death in 1856. It seemed that merely establishing Utopian communities was not enough by itself to convince humankind of their utility. Something more was needed.

One means of making an impact was developed by another group of Utopian socialists, the Saint-Simonians, founded by Claude-Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825), who had had a career more adventurous than most: he had served under Washington at Yorktown in 1781, narrowly escaped the guillotine during the Revolution of 1789, and been incarcerated as a lunatic with the Marquis de Sade (1740–1814) at the asylum in Charenton. He continued to live a troubled life thereafter, even attempting suicide in 1823 by shooting himself. His central concern was with developing a rational form of religion in which people would obtain eternal life ‘by working with all their might to ameliorate the condition of their fellows’. He attracted a number of followers, including not only carbonari but many highly trained, educated and talented people, particularly those associated with the coming world of industry, such as engineers, technologists, bankers and the like. Saint-Simon’s secretary was Auguste Comte (1798–1857), later the founder of sociology, author of Industry (1816–18) and Of the Industrial System (1821–2). Comte too was a troubled man; he was admitted to a lunatic asylum briefly and tried to commit suicide in 1827 by jumping off a bridge into the river Seine. He was no more successful in doing away with himself than his master had been, and survived for another thirty years, following Saint-Simon in devising a new ‘religion of humanity’ and coining the word ‘altruism’. His six-volume Course of Positive Philosophy, published between 1830 and 1842, was to have a major impact not only in France but in other countries too through the sociological doctrine of ‘positivism’.

Saint-Simon’s movement survived his death in 1825. He was succeeded as its leader by the bank cashier Prosper Enfantin (1796–1864), who had led a group of Napoleonic enthusiasts in armed resistance to the Allies as they invaded Paris in 1814 and subsequently joined the carbonari. Enfantin declared the improvement of ‘the poorest and most numerous class’ to be the will of God. But the lead in this task would be taken by scientists, engineers and industrialists. One Saint-Simonian, the former carbonaro and printer Pierre Leroux (1797–1871), introduced the term ‘socialism’ into French political vocabulary in 1834 (he also invented the word ‘solidarity’). Enfantin subsequently became a director of the Paris and Lyons Railway. Many of Saint-Simon’s disciples played a significant role in French industrial, economic and academic life in the 1850s and 1860s. His ideas also informed the writings of Louis Blanc (1811–82), tutor to the son of an ironmaster. In 1839, Blanc published an immensely popular book, The Organization of Labour, which proposed factories based on profit-sharing among the workers, financed initially by loans. Blanc rejected the hierarchical aspects of Saint-Simon’s philosophy and replaced his slogan ‘To each according to his works’ with a new one: ‘To each according to his needs’.

Among the Utopians it was above all Fourier who propounded the identity of women’s emancipation and general human emancipation, a belief shared by Flora Tristan: ‘The extension of privileges to women,’ he wrote, ‘is the general principle of all social progress.’ He too compared women to slaves: marriage for them was ‘conjugal slavery’. In the phalanstery, women would have fully equal rights and would be free to marry and divorce as they wished. Just as Cabet invented the word ‘communism’, so Fourier invented the word ‘feminism’. The Saint-Simonians were equally preoccupied with women’s place in society. Enfantin proclaimed ‘the emancipation of women’ as a central goal of a new Church that he would lead. He included in this concept, however, the ‘rehabilitation of the flesh’, and his advocacy of the sexual emancipation of women brought a conviction for offending public morality in 1832. Far more conventional was Cabet, who, perhaps surprisingly, thought that the main constituent unit of communist society would not be the individual but the heterosexual married couple and their children, so that shared childrearing did not come into his vision. Every woman should be educated, but the aim of her education should be to make her ‘a good girl, a good sister, a good wife, a good mother, a good housekeeper, a good citizen’.

Utopian socialism was not confined to French thinkers. The Welshman Robert Owen (1771–1858), born in humble circumstances, rose to become a factory manager and assumed control of the New Lanark cotton mill in Glasgow after marrying the owner’s daughter and organizing a consortium to buy him out. Owen found the workers dissolute and degraded, so he set up schools for the children and opened the first ever co-operative store, selling goods cheaply to the workers and sharing out the profits with them. New Lanark became famous as a model factory community, and led Owen to declare in 1827 that it could become the basis for the establishment of co-operatives across the industrial world. His mission was to overcome industry’s ‘individualization’ of the human being and replace this atomized society with what he called a ‘socialist’ one – the first time the term had been used in English. He invested heavily in communitarian experiments in the United States, most notably ‘New Harmony’, which flourished briefly between 1824 and 1829. His ideas had a considerable influence among the new industrial workers in Britain. But he eventually withdrew into another obsession of the Utopians, the foundation of a new Church. Owen became the self-styled ‘Social Father of the Society of Rational Religionists’, before converting to Spiritualism and enjoying conversations with the shades of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson until he too passed over to the other side, in 1858.

Owen, Fourier, Cabet and other Utopian thinkers spread their ideas to workers like the German tailor Wilhelm Weitling (1808–71), who in works such as Humanity: As it is and as it should be (1838) and The Gospel of Poor Sinners (1845) traced back communism to the doctrines of early Christianity and proposed to force it onto society by a millenarian uprising of 40,000 convicted criminals. However, few of the Utopians had roots in the artisanal world, let alone the world of the new industrial working class. When they did, like the French artisan Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–65), who grew up as the son of an impoverished cooper and himself trained as a compositor, their ideas were very different from those of theorists such as Enfantin. Thrown out of work in 1830, Proudhon embarked on a career as a writer, putting forward in a long series of books and pamphlets what he called ‘a people’s philosophy’. In his book What is Property?, published in 1840, he famously answered the question posed in the title by declaring: ‘Property is theft’. By this phrase, he did not intend to dismiss all private property; rather, he wanted society to own all property but to lease it all out to prevent profiteering and unfair distribution. Nevertheless, his declaration resonated across the century as a slogan for socialists, communists and anarchists alike. Proudhon was vehemently opposed to female equality. If women obtained equal political rights, he declared, men would find them ‘odious and ugly’, and it would bring about ‘the end of the institution of marriage, the death of love and the ruin of the human race’. ‘Between harlot or housewife,’ he concluded, ‘there is no halfway point.’

In this, as in other respects, Proudhon’s ideas differed from those of most Utopian socialists. What they had in common with them, however, was a determination to deal with the new political world made by the French Revolution of 1789, and the new economic and social world in the throes of being created across Europe by the advance of industrialism. This determination was shared by some variants of Hegelianism, another, more academic tradition of radical thought in the first half of the nineteenth century. Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel (1770–1831), who grew up in south-west Germany under the influence of the Enlightenment, was an admirer of the French Revolution, and of Napoleon, whom he witnessed entering Jena after winning the battle of 1806. Following a variety of teaching positions, Hegel was appointed to the Chair of Philosophy in Berlin in 1818, where he remained until his death from cholera in 1831. An atheist, he replaced the concept of God with the idea of the ‘World-Spirit’ of rationality, which he believed was working out its purposes through history in a process he called ‘dialectical’, in which one historical condition would be replaced by its antithesis, and then the two would combine to create a final synthesis. As he became more conservative, Hegel began to regard the state of Prussia after 1815 as a ‘synthesis’ requiring no further alteration. Not surprisingly, he was soon known as ‘the Prussian state philosopher’. But his core idea of ineluctable historical progress held a considerable appeal for radicals in many parts of Europe. In Poland the art historian Józef Kremer (1806–75) propagated Hegel’s ideas in his Letters from Cracow, the first volume of which was published in 1843. The French philosopher Victor Cousin (1792–1867) made a pilgrimage to see Hegel in 1817. ‘Hegel, tell me the truth,’ he demanded: ‘I shall pass on to my country as much as it can understand.’ The great man, having worked his way through Cousin’s Philosophical Fragments, was not impressed: ‘M. Cousin,’ he wrote scornfully, ‘has taken a few fish from me, but he has well and truly drowned them in his sauce.’

In the emerging world of the intelligentsia in Russia during the 1830s and 1840s, as Alexander Herzen, author of Who is to Blame? (1845–6), one of the first Russian social novels, later remembered, Hegel’s writings were discussed deep into the night. ‘Every insignificant pamphlet . . . in which there was a mere mention of Hegel was ordered and read until it was tattered, smudged, and fell apart in a few days.’ Hegel’s dialectic sharpened vague perceptions of the differences between East and West and forced Russian intellectuals to take sides. The literary critic Ivan Kireyevsky (1806–56), whose religious father was so vehemently hostile to the atheism of Voltaire that he bought multiple copies of the Frenchman’s books solely in order to burn them in huge piles in his garden, attended Hegel’s lectures in Berlin and concluded that Russia was destined to belong to the East, founding its society on collectivism rather than individualism, and building its moral character on the doctrines of the Orthodox Church. However, Hegel’s philosophy of history convinced others that Russia was on a preordained trajectory towards a liberated future by acquiring the freedoms common in the West. The young literary critic Vissarion Belinsky (1811–48) began labelling everything he thought backward in the culture and politics of his native land ‘Chinese’. Herzen drew similar consequences from a reading of Hegel, but stopped short of advocating violent revolution in order to achieve them.

That step was taken by the most radical of the Russian Hegelians, Mikhail Bakunin (1814–76), who imbibed the works of the German philosopher while studying in Moscow. Bakunin was a man of violent, volcanic temperament, described by his friend Belinsky as ‘a deep, primitive, leonine nature’, also notable, however, for ‘his demands, his childishness, his braggadocio, his unscrupulousness, his disingenuousness’. In 1842, by now in Paris, Bakunin published a lengthy article urging ‘the realization of freedom’ and attacking ‘the rotted and withered remains of conventionality’. The article breathed a spirit of Hegelianism so abstract that for long stretches it was almost incomprehensible. But it ended with a chilling prophecy of the violent, anarchist extremism of which Bakunin was the founding father: ‘The passion for destruction is also a creative passion.’ These sentiments expressed the influence of a group of German philosophers known as the Young Hegelians, whose atheism led to their expulsion by the pious King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV (1795–1861), soon after he came to the throne in 1840. Bakunin met them in Paris, publishing his article in one of their short-lived magazines, edited by Arnold Ruge (1802–80). It was also in Paris that Bakunin met another Hegelian, Karl Marx (1818–83), who was to be his rival in the small and intense world of revolutionary activists and thinkers for most of the rest of his life. The two men disliked each other on first sight. Marx, as Bakunin later recalled, ‘called me a sentimental idealist, and he was right. I called him morose, vain and treacherous; and I too was right.’

In the longer run, it was Marx who was to prove the more influential. Born on the western fringes of Germany, in the small, declining provincial town of Trier, in the Rhineland, Karl Marx gravitated towards the Young Hegelians at the University of Berlin, one of whom, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–72), was the source of Marx’s famous statement ‘Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world: the point is to change it.’ Marx became a freelance writer, penning articles for a recently founded radical paper based in Cologne, the Rheinische Zeitung. The paper was soon closed by the authorities in April 1843, and three months later Marx moved to Paris. His reading of the English political economists made him pessimistic about the economic prospects of the working class. His reading of the French socialists led him to see in the abolition of private property and the establishment of communal and collective forms of labour the way to overcome the alienation of the workers’ labour through the appropriation of its products by the employers. Socializing with radicals in Paris also brought Marx for the first time into contact with Friedrich Engels (1820–95), who became his lifelong collaborator. Marx wrote a number of polemics in the 1840s that reflected the fractious mood of the émigré circles among whom he now moved. It was socialists like Proudhon who were making the running, a situation which Marx’s vehement critique of the Frenchman’s ideas, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), had no real chance of changing. Still, all of these ideas, building on the legacy of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and the French Revolution, were to play a part in the revolutionary events that brought the decade to a close.

NATIONALISM AND LIBERALISM

More immediately, however, in the 1830s and 1840s, it was the ideas of nationalism that had the greatest and most disruptive impact. It is common to define nationalism as the demand for a state respondent to the sovereign will of a particular people, but many nationalists in the first half of the nineteenth century stopped well short of embracing this radical principle. Some sought to free their own nation from a foreign yoke. Most persistent here were the Poles, who sought independence from tsarist Russia, the Habsburg Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, which had carved up the dysfunctional Polish state between them in the eighteenth century. But most other nationalists of this type only wanted greater autonomy within a larger political structure, or simply the official recognition of their language and culture. In the Habsburg Monarchy, distinctive national groups like the Czechs and Hungarians fell into this category; none actively campaigned for the dissolution of the monarchy itself. In Finland the Fennoman movement, led by Johan Vilhelm Snelmann (1806–81), a teacher and philosopher who advocated the use of Finnish rather than Swedish in the schools (although he himself only spoke the latter), did not raise any demand for independence from Russia. A second type of nationalism sought to bring together a single nation split into a number of different independent states – notably German and Italian – and here, the demand from the beginning was for complete sovereignty. Of course, these categories were not entirely separate from one another. Uniting Italy meant throwing off the Austrian yoke in the north of the peninsula; uniting Germany meant coming to an arrangement with Denmark and in particular the Habsburg Monarchy, both of which covered a part of the German Confederation but had most of their territory and inhabitants outside it. Still, it is important not to read back later demands for independence into the nascent nationalism of the 1830s and 1840s. Before mid-century, indeed, nationalism for many was as much a means to an end as an end in itself, a means to bring about liberal political and constitutional reform in the face of the conservative order enforced by the Holy Alliance and the police regime of the German Confederation under Prince Metternich.

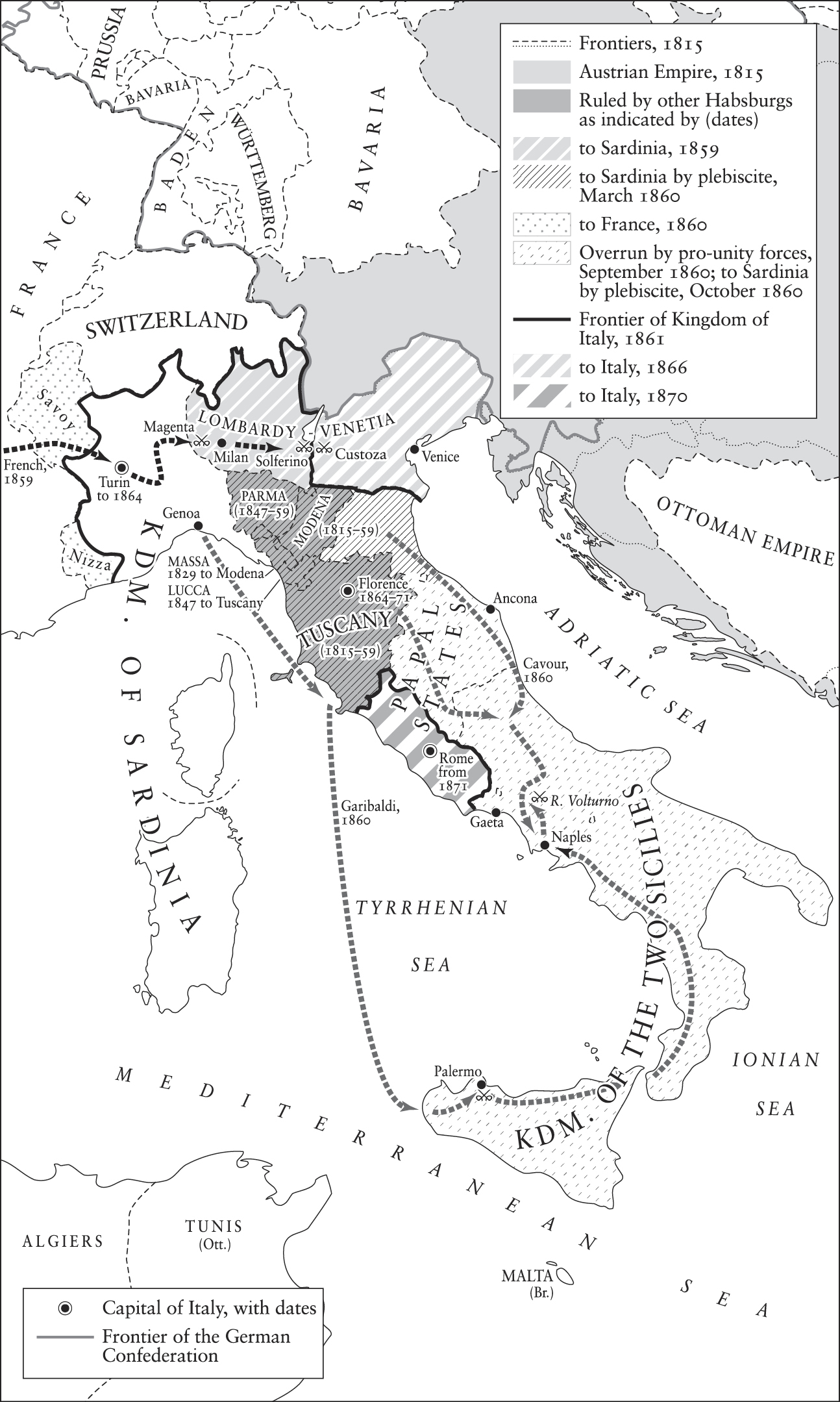

It would also be unwise to read back into the 1830s and 1840s too much of the later aggressiveness and egoism of European nationalism. Giuseppe Mazzini, the best-known European nationalist of his age, believed in a United States of Europe, composed of free and independent peoples in a voluntary association with each other. The disunity of the 1831 urban insurrections in northern Italy and their easy suppression by the Austrians convinced him that the carbonari, to which he belonged, had to be replaced by a truly national organization, dedicated above all to organizing the expulsion of the Austrians from the peninsula. Living secretly in Marseille, he founded an association called Young Italy, possibly in imitation of the literary movement Young Germany founded shortly before. Despite its conspiratorial trappings, Young Italy had a clear programme – Italian unification on a democratic and republican basis. It also compiled membership lists, charged subscriptions, and employed a courier service to keep members in various towns and cities in touch with one another. Soon the members of Young Italy numbered thousands, inspired by Mazzini’s tireless campaigning, his incessant pamphleteering, and the fact that he was apparently the ‘most beautiful being, male or female’ that people who encountered him said they had ever seen. Metternich declared membership punishable by death. Carlo Alberto, the King of Piedmont-Sardinia, had twelve army officers who were involved in a plot to stage a military uprising under Mazzini’s influence early in 1833 publicly executed. Mazzini himself was condemned to death in absentia and the sentence read out in front of his family home in Genoa. Metternich succeeded in getting him expelled from France, but Mazzini continued to run Young Italy from Switzerland. He now focused his numerous plots on Piedmont: one of them, like so many betrayed to the Piedmontese authorities, involved a young naval officer, Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had joined Young Italy after meeting a member on a trading expedition to the Black Sea. Also condemned to death in absentia, Garibaldi fled to South America, where he took part in the ‘War of the Ragamuffins’ in Brazil before fighting in the Uruguayan Civil War.

Working through correspondence, conducted after 1837 from London, Mazzini created individual national movements under the aegis of Young Italy: Young Austria, Young Bohemia, Young Ukraine, Young Tyrol and even Young Argentina came briefly into being. Young Poland played a significant role in the 1830 uprising. The most enduring and important organization of this kind was Young Ireland, a term mockingly attached by the English press to a movement founded in 1840 by Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847); it had nothing to do with Mazzini, who did not think that Ireland should be independent; it eschewed violence and insurrection, and it dedicated itself not to the creation of a new nation but to the repeal of the Act of Union with England passed in 1800. But through the organizations he actually did found, Mazzini had changed the terms and tactics of nationalism. Nationalists had learned to co-ordinate their efforts within each particular country, and a strong dose of realism had entered their discourse, causing all but the Poles to recognize that insurrections were unlikely to succeed by themselves, and that the formation of secret societies was not leading anywhere: nationalists needed a programme and a formal organization, equipped with a propaganda apparatus and aimed at securing democratic support.

Under the leadership of Metternich, the Habsburg Empire continued indeed to be the major obstacle that lay in the path of nationalist movements – in Italy, Bohemia, Germany, Hungary and – along with Russia and Prussia – in Poland. Austria had led the European states in the overthrow of Napoleon; for thirty years, from 1815 to 1845, Austrian dominance in Europe was unquestionable. Following Napoleon I’s abolition of traditional legislatures such as feudal Estates, few outlets remained for popular discontent. The Emperor Franz I refused to introduce any new constitutional arrangements to his domains in northern Italy. ‘My Empire,’ he remarked, ‘resembles a ramshackle house. If one wishes to demolish a bit of it one does not know how much will collapse.’ In central Italy, Gregory XVI, who was elected pope in 1831, ruled the Papal States through a militia of ‘centurions’ who suppressed all criticism of the corruption and inefficiency of his administration. So chaotic was the state of affairs in his dominions that the papal government did not even manage to prepare a state budget for the last ten years of his pontificate. In Piedmont-Sardinia throughout the 1830s and the first half or more of the 1840s, the fear of conspiracy and revolution kept Carlo Alberto of Piedmont on the Austrians’ side in northern Italy. Yet he was pessimistic in the longer run. ‘The great crisis,’ he wrote in 1834, ‘can only be more or less delayed, but it will undoubtedly arrive.’

Avoiding it was one of the aims of the moderate liberal reformers who arrived on the political scene in the 1840s. As with similar figures elsewhere in Europe, they looked above all to Britain as an example. The Milanese reformer Carlo Cattaneo (1801–69), an ex-carbonaro who had turned to more moderate ways, thought that ‘peoples should act as a permanent mirror to each other, because the interests of civilization are mutually dependent and common’. In Piedmont, the most influential of the moderates in the long run was Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour (1810–61), a Protestant who had travelled widely in Britain and France and supported economic progress, railway-building and the separation of Church and State. As liberal sentiment spread among the educated classes, above all in northern Italy, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston warned the Austrian ambassador in London that it was time to make concessions: ‘We think ourselves conservative in preaching and advising everywhere concessions, reforms, and improvements, where public opinion demands them; you on the contrary refuse them.’ But change in Italy seemed to be heralded by the election of Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti (1792–1878) as Pope Pius IX on 16 June 1846. The new Supreme Pontiff amnestied political prisoners, relaxed the censorship rules, and appointed commissions to improve the Papal States’ administration, laws and educational provision. His summoning of a consultative assembly sent shock waves through the Italian states. Others followed suit. In Tuscany censorship was partially abolished in May 1847, a legislature was convened following demonstrations in a number of cities, and in September 1847 the Grand Duke Leopold II (1797–1870) appointed a moderate liberal government. In Piedmont, Carlo Alberto granted elected communal councils and limitations on censorship in October 1847. In the Habsburg Monarchy, Metternich’s refusal to relax the censorship rules in 1845 had no effect since nationalist and liberal literature poured in from outside, including French, English and German newspapers. The crisis seemed to be coming. ‘We are now,’ warned the former civil servant Viktor Baron von Andrian-Werburg (1813–58), author of an influential, pessimistic book on the future of the multinational monarchy, ‘where France was in 1788.’

This seemed to be particularly the case in the Hungarian provinces of the Habsburg Empire. The leading reformer István Széchenyi’s Anglophilia made him a gradualist, desiring ‘to change the condition of the fatherland with as little fanfare as possible’. He believed in bringing different social classes together in harmony, a purpose he thought could be fostered by horse-racing, for which he had conceived a passion following a visit to Newmarket – he founded the Hungarian Derby to this end in 1826. Following the Polish uprising and a devastating cholera epidemic in 1831, the Hungarian Diet met in 1832 with a programme of reform, but the emperor vetoed even the modest measures that got through. In 1837 the lawyer and journalist Lajos Kossuth (1802–94), who published Hungary’s first parliamentary reports, was arrested for sedition. This sparked a serious crisis, as Kossuth’s supporters in the Diet forced Metternich to climb down and release him and other imprisoned liberals in May 1840. The same Diet removed legal barriers to the establishment of factories, approved the building of the country’s first railway line, and relaxed restrictions on the occupation and residence of Hungary’s Jews. Further reforms gave Protestants civil and legal equality with Catholics and legitimated mixed-religion marriages. But this did not satisfy the liberals. Kossuth was joined by the leading moderate Ferenc Deák (1803–76), and together they produced a statement of their aims. In the new Diet of 1847, to which Kossuth was elected by a triumphant majority, Metternich felt obliged to make concessions, including the abolition of customs barriers on the Austrian border with Hungary. But it was too late: these measures altogether failed to appease the growing nationalist opposition, and divisions between the Hungarian liberals and the Monarchy’s leadership in Vienna continued to deepen until they became irreconcilable. Within only a few months they had broken out into open conflict.

In Switzerland, reforms passed by moderate liberals whose strength was in the towns and cities of the Protestant cantons ran into fierce objections from the largely Catholic, more rural parts of the Confederation. When the liberals passed a centralist constitution and began closing Catholic monasteries, the conservative cantons reacted by forming a ‘special league’ in 1843, the Sonderbund, in violation of the Federal Treaty of 1815. Both sides began to mobilize, and in November 1847 hostilities commenced. Federal troops captured the Sonderbund stronghold of Fribourg and installed a liberal government, which promptly expelled the Jesuits, as liberal and reforming governments everywhere were wont to do. In the Battle of Gislikon, the last pitched battle ever to involve the Swiss Army, thirty-seven soldiers were killed and one hundred wounded. For the first time in military history, horse-drawn ambulances arrived on a battlefield and took away the wounded. Further skirmishes led to the surrender of the Sonderbund on 29 November 1847. A new, more liberal constitution was passed a few weeks later.

The Swiss Civil War was a foretaste of conflicts to come in other parts of Europe. The revolutions of the early 1830s had only been partially negated by the repressive measures undertaken by Metternich in most parts of the German Confederation, and a good number of the states now had elected legislative assemblies that provided a forum for liberal politicians. Conservative rulers did not appreciate this change in the political climate. In 1837, when Queen Victoria acceded to the British throne, the Salic Law prevented her from doing the same in Hanover, and her uncle, Ernest August, Duke of Cumberland (1771–1851), already notorious for the extreme conservative views he was in the habit of expressing in the British House of Lords, ascended the Hanoverian throne and immediately abrogated the constitution of 1833, demanding an oath of loyalty from all the state’s employees. Seven professors at Göttingen University, including the brothers Jacob Grimm (1785–1863) and Wilhelm Grimm (1786–1859), compilers of the famous folk tales, refused to swear the oath and were dismissed from their posts. Their action achieved nothing in the short run – the constitution stayed abrogated – but aroused liberal sympathies all over Germany. In 1840 the accession of Friedrich Wilhelm IV as King of Prussia prompted liberal hopes of reform. Oppositional clubs and societies sprang up everywhere, and liberals got themselves elected to previously dormant city councils, which began petitioning the king to summon a constituent assembly. In an attempt to defuse the situation, Friedrich Wilhelm summoned the provincial Estates to a United Diet in 1847, prompted not least by the need to raise more taxes in the middle of the economic crisis of the late 1840s. When he spurned calls for a constitution, the majority rejected his request for tax reform. The king dissolved the Diet, but its potential role as a focus for constitutional reform had become clear.

In Bavaria, King Ludwig I (1786–1868) was becoming increasingly unpopular in view of the repressive, pro-clerical policies of his minister Karl von Abel (1788–1859) – nearly a thousand political trials were held during Ludwig’s reign, which began in 1825. What really undermined the king’s authority, however, was the arrival in Munich of the Spanish dancer Lola Montez (1821–61). Famous for her erotic ‘Spider Dance’, at the climax of which she lifted her costume to reveal that she was not wearing any undergarments, Lola was a veteran of previous affairs with the virtuoso pianist and composer Franz Liszt (1811–86) and (possibly) the novelist Alexandre Dumas. Despite her exotic-looking, dark beauty, Lola was not actually Spanish at all. Her real name was Eliza Gilbert and she was Irish, the daughter of the county sheriff of Cork. She made an instant impression on King Ludwig: when he met her, overwhelmed by her shapely form, he felt emboldened to ask whether her bosom was real, upon which she is said to have ripped off her bodice to prove that indeed it was. Soon she had become the king’s mistress. He showered her with gifts, gave her a generous annuity, and ennobled her as Countess of Landsfeld. When Abel objected (‘all those who plot rebellion rejoice,’ he warned the king), she had him dismissed. The pillorying of Ludwig in popular pamphlets and broadsheets reminded many of the scurrilous attacks on the French King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette that had done so much to discredit the French monarchy in 1789. A similar loss of legitimacy, though without the additional element of farce, undermined other monarchs in Germany too. The refusal of Wilhelm I of Württemberg (1801–64) to grant reforms led to the formation of an energetic liberal opposition, while the stubborn conservatism of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, Ludwig II (1777–1848), led to the victory of an organized liberal movement under the lawyer and former Burschenschaft member Heinrich von Gagern (1799–1880) in the elections to the state Diet in 1847.

The model polity that inspired such men was the liberal state in Britain, according to the German encyclopedist Carl Welcker (1790–1869) ‘the most glorious creation of God and nature and simultaneously humanity’s most admirable work of art’. What impressed European liberals was the ability of the British political system to avoid revolution through timely concessions to liberal demands. In power from 1832 to 1841, the Whigs passed legislation reforming the Poor Law (1834), reshaping the criminal law, and creating a new, uniform system of municipal government based on elected councils (the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835). Over a hundred Royal Commissions were set up between 1832 and 1849, with experts being examined, information compiled, and their reports, published as ‘Blue Books’, selling thousands of copies across the land and providing a detailed factual basis for public debate. When the Whigs were finally ousted in the General Election of 1841, a new kind of Tory came to power as Prime Minister – the efficient, hard-working Sir Robert Peel, who as Home Secretary under both Lord Liverpool (1770–1828) and the Duke of Wellington had simplified the criminal law and famously, in 1829, established London’s blue-uniformed Metropolitan Police Force, popularly dubbed ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’. Reticent, undemonstrative, upright and rationalist in character and approach, Peel was nonetheless animated by a powerful Evangelical conscience – one which, for example, had caused him to oppose equal rights for Catholics in the 1820s. Peel’s administration set up a uniform currency with notes issued by the Bank of England. The Companies Act of 1844 required companies to be registered and to publish their balance sheets, a necessary measure in an age of manic railway speculation. Peel also put the national finances in order by introducing an income tax, grudgingly accepted by the political class.

If both Whigs and Tories were, in European terms, moderate liberals, then there were also the equivalents in Britain of the radicals and democrats who had emerged on the Continent. Many forms of working-class self-help organizations emerged in the new industrial districts of the country in the 1830s and 1840s, notably friendly societies such as the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers’ Society, founded in 1844, which set up co-operative stores where members could buy goods cheaply. But the most overtly political of these groups was the Chartist movement, so called because it centred on a document called the Working Men’s Charter, drawn up in May 1838 by a group of radical Members of Parliament. Unlike the Jacobins or the Cato Street conspirators or the Utopian Socialists, the Chartists believed in the parliamentary system, but they wanted the House of Commons to be elected on a democratic vote with a secret ballot and equal electoral districts. They found a powerful orator in the Irishman Feargus O’Connor (1794–1855), a sometime MP and advocate of the repeal of the Act of Irish Union. Over six feet tall, with a ready wit, O’Connor appealed to ‘unshaven chins, blistered hands, and fustian jackets’ rather than the respectable classes. At a series of huge meetings, he addressed tens of thousands of Chartists in his booming voice, winning them over with his powerful rhetoric.

The climax of the Chartists’ agitation came with the London convention in February 1839 at which quarrels between moderates and radicals (some of whom wore Phrygian bonnets) revealed a serious split within the movement. When a petition adorned with 1,283,000 signatures, urging the House of Commons to adopt the Charter, was rejected in July 1839, the radical wing became more extreme in its rhetoric, and a number of its leaders were arrested for seditious libel and sent to prison. In Newport, Monmouthshire, the Chartist John Frost (1784–1877) organized a protest demonstration that turned into an uprising when several thousand miners, equipped with bludgeons and firearms, marched on the local jail to free fellow Chartists who had been arrested. Troops were summoned and fired on the crowd, killing more than twenty. Altogether 500 Chartists were in jail by 1840. After a second petition, with more than 3,250,000 signatures, was rejected by the House of Commons in 1842, Chartism died down, and O’Connor turned his energies to land reform. The mantle of the country’s leading pressure group fell on the Anti-Corn-Law League, which enjoyed strong middle-class backing for the ending of import tariffs on corn, and mounted a sophisticated and well-organized campaign that ended in success in 1846. The aristocratic Whigs voted with Peel, recognizing the need for a concession despite their identification with the landowning interest, but a strong minority of Tory MPs, led by the opportunistic young novelist-politician Benjamin Disraeli and counting among its number many gentry farmers, voted to support the Corn Laws and split the party, with the result that the Whigs were returned to office. Chartism was undercut by an improvement in the economy and by Peel’s demonstration through his reforms of the integrity of the political Establishment. Moderate liberals, incorporated both in the English Whigs and in Peel’s reformist Tories, had clearly seen off the democrats and radicals for the time being.

The dilemmas of moderate liberalism were nowhere better illustrated than in France, where its representatives had come to power in the 1830 Revolution. Overcoming the chronic political instability of the 1830s, François Guizot, a Protestant historian whose father had been guillotined during the Reign of Terror, managed to establish a stable ministry in 1840, which lasted until 1848. He became more conservative over time. ‘Not to be a republican at 20 is proof of a want of heart,’ he remarked: ‘to be one at 30 is proof of a want of head.’ An Anglophile who translated Shakespeare and published a collection of English historical documents in thirty-one volumes, Guizot was the arch-apostle of English-style constitutional monarchy. His commitment to the established order was unquestionable. His ambition, one critic said, was ‘to be incorporated into the Metternich clique of every country’. His response to those who complained at not having a vote because they did not have the 1,000 francs a year needed as a qualification, laid bare the materialism at the heart of the July Monarchy: ‘Enrich yourselves!’ The restrictive franchise remained unaltered until the regime’s end. In Britain, by contrast, the electorate was already proportionately larger even before the reform of 1832 (3.2 per cent of the British population as against 0.5 per cent of the French), and the fear of revolution, sparked in London by events in Paris two years before, had brought about a substantial widening of the electorate that for many years defused the campaign for democracy.

Guizot’s main achievement was in the sphere of education, where he laid down the principle that every commune, or group of communes, had to have a teacher-training college and a primary school, with a secondary school in each town containing over 6,000 inhabitants. Yet he encountered criticism for his restrictions on press freedom, imposed in 1835, which resulted in over 2,000 arrests and led to a show trial of 164 seditious journalists. Demands for social reform, he said, were ‘chimerical and disastrous’. The Factory Act of 1841, which forbade the employment of children under the age of eight in factories with machinery, remained the only law of its kind until 1874 and was far from effective. On the other hand, laws were passed to facilitate railway-building, which gathered pace in the 1840s. No wonder that Balzac described the July Monarchy as an ‘insurance contract drawn up between the rich against the poor’. Guizot’s government was beset by scandal, especially in 1847, when it emerged that the Minister of Public Works, Jean-Baptiste Teste (1780–1852), had accepted 100,000 francs from an ex-Minister, General Amédée Despans-Cubières (1786–1853), as a bribe for allowing him to renew a salt-mining concession. Corruption of this kind increasingly called the July Monarchy into question as the decade neared its end.

THE SPECTRE OF 1789

The first sign of a renewal of revolutionary violence was in Poland. The crushing of Polish autonomy by Russia in the early 1830s had driven many Polish nationalists abroad, where the national-democratic ideologies and secret societies of the post-Napoleonic era focused their energies and gave them a purpose. Typical was the Paris-born poet Ludwik Mierosławski (1814–78), whose godfather was one of Napoleon I’s marshals. Mierosławski had fought in the 1830 uprising, and belonged not only to Young Poland but also to the carbonari. After lengthy preparations, his plans for a simultaneous insurrection in Prussia, Cracow and Galicia finally reached maturity in 1846. But the Prussian police got wind of the conspiracy and arrested the ringleaders in their part of the partitioned land. The Austrian governor of Galicia felt too weak to oppose the armed noble rebels of the province and enlisted a local peasant leader, Jakub Szela (1787–1866), who rashly promised an end to serfdom for all who joined his forces. Matters got out of hand as a classic jacquerie of major proportions developed. Armed bands of peasants burned 500 manor houses, butchering their inhabitants and offering the severed heads of the aristocratic landlords to the Austrian authorities, who rewarded them with bags of salt. Altogether nearly 2,000 noble estate owners were massacred. Eventually the Austrian Army arrived to restore order. Szela was rewarded with a medal and a plot of land, and while serfdom, predictably, was not abolished, the revolt had sounded its death knell. An Austro-Russian Treaty signed on 16 November 1846 abolished the status of Cracow, the centre of the revolt, as a free city and merged it into Galicia.

The Galician uprising might have failed, but it sent shock waves across the Continent. Moderate liberals everywhere were spurred into action, fearing that without serious constitutional reform social revolution would overwhelm them. Democrats and socialists saw their chance. Authoritarian governments were shaken out of their complacency and started to make concessions. Underpinning all this were the catastrophic crop failure and potato blight that plunged the European economy into depression from 1846 onwards. Starving and desperate people flocked to the towns in huge numbers. Artisans were thrown into destitution, their income slashed just as food prices were soaring. Compounding this disastrous situation was a massive increase in the number of university students, from 9,000 in Germany during the 1820s to around 16,000 in the 1840s; they too found themselves on the breadline and, just as bad, without a prospect of a job after graduating. The crisis of the late 1840s was also a crisis of the industrial age. The centres of the events of 1848 were all in areas affected by British industrial competition, which was undercutting continental manufactures. The collapse of demand for manufactured goods caused the Borsig railway and engineering works in Berlin to lay off a third of its workforce at the beginning of March 1848, while a wave of bankruptcies swept over the textile industry in Bohemia. Capital cities in Europe were the fulcrum of revolution in 1848, but they were also major centres of industry. Here the formation of a new working class was as advanced as anywhere, and the street demonstrations that drove on the revolution were influenced by the ideas of the Utopian socialists of one variety or another.

Monarchs and princes and their leading ministers expected revolution – some of them had prophesied it for many years – and the expectation all too easily became self-fulfilling. The year 1848 marked the temporary displacement on the European Continent of English gradualism by French insurrectionism. Many people expected 1789 to happen all over again. In conformity with this script, it was in France that the revolution began. Middle-class opponents of Guizot and Louis-Philippe began holding a series of huge banquets, seventy in all during the year 1847, mostly in Paris but also in twenty-eight départements in the provinces, at which speeches were made demanding the reduction of the tax threshold for the right to vote. At one such banquet a large but peaceful crowd sang the Marseillaise outside, while 1,200 electors sat down to a candlelit dinner of cold veal, turkey and suckling pig inside a series of vast tents at twelve tables, each with a hundred places set for the participants, in what a contemporary newspaper described as a ‘truly magical spectacle’. A seventy-piece orchestra played ‘patriotic airs’. Toasts were raised ‘To national sovereignty!’, ‘To democratic and parliamentary reform!’, ‘To the deputies of the Opposition!’ and ‘To the improvement of the lot of the labouring classes!’. ‘What taste!’ exclaimed the writer Gustave Flaubert (1821–80): ‘What cuisine! What wines and what conversation!’ One speaker after another mounted a tribune to deliver speeches denouncing the government. A supporter of the movement made a pointed distinction between the cold veal (veau froid) eaten at the banquet and the golden calf (veau d’or) worshipped by the elite supporters of Guizot’s regime. A satirical broadside imagined conservatives holding their own version of the banquets with beefsteak – a reference to Guizot’s Anglophilia – and brie, an allusion to his own constituency in Normandy. They were clearly not going to consume ‘reformist veal’ or ‘Jacobin asparagus’.

As the campaign gathered pace, its threat to the stability of the July Monarchy became obvious. The political writer and historian Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59), already well known for his two-volume study of Democracy in America (1835), asked the Chamber of Deputies on 27 January 1848 ‘Do you not smell . . . a whiff of revolution in the air?’ The influence of Cabet and the socialists, he thought, had been increasing rapidly. Ignoring this warning, Guizot’s government decided to outlaw the banqueting campaign. The organizers riposted by calling for a huge procession to precede the next banquet, openly defying the ban on public demonstrations. As the demonstration went ahead, the troops defending the Foreign Ministry, under heavy pressure from the crowd, panicked and opened fire, killing more than eighty of the demonstrators. Within a few hours more than 1,500 barricades had gone up all over Paris. Adolphe Thiers was appointed Prime Minister; but soldiers of the National Guard greeted the king’s attempt to rally them with cries of ‘Long live reform! Down with the ministers!’ The paralysis of the regime was complete. Louis-Philippe went back to his chambers in the Tuileries Palace, slumped into an armchair, with his head in his hands, as Thiers, sunk in gloom, exclaimed repeatedly: ‘The sea is rising! The sea is rising!’ Louis-Philippe gave in. ‘I abdicate,’ he mumbled from his armchair, repeating the words more loudly a few minutes later. Accompanied by loyal troops, the king and his family and a few retainers decamped to the coast, where they were taken in hand by the British consul in Le Havre, George Featherstonhaugh. His whiskers shaved off, his face disguised in spectacles, his body muffled in a thick scarf and a heavy jacket, Louis-Philippe, following the consul’s plan, boarded a ferry, where Featherstonhough greeted him in English in an elaborate pantomime of deception that bordered on the farcical (‘Well, uncle! How are you?’ ‘Quite well, I thank you, George.’) On 3 March 1848 the boat landed at Newhaven, and ‘Mr. Smith’, soon to be followed by other members of his family, began his life in exile. The July Monarchy was over; France’s 1848 Revolution had begun.

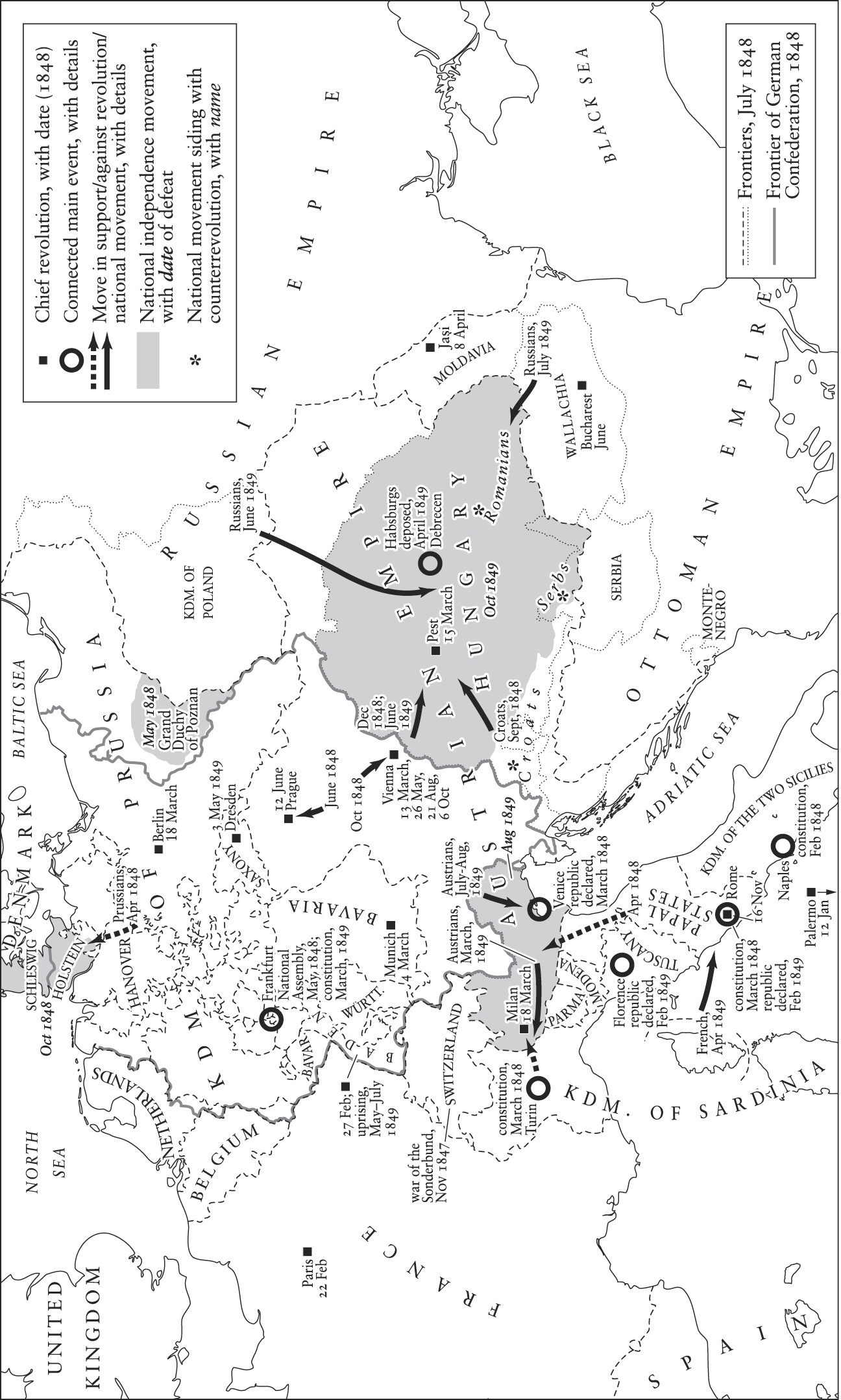

While 1789 was in everybody’s minds during these events, the revolution of 1848 differed from its predecessor in many respects. Most obvious was its European dimension. In the 1790s the French revolutionaries had spread their ideas across large swathes of the Continent by force of arms. In 1848 they did not need to do this; revolutions broke out in many different countries almost simultaneously. A large part of the reason for this lay in the vastly improved state that communications had reached by the middle of the nineteenth century. Although still in its infancy, Europe’s railway network, assisted by better roads and faster, steam-powered ships, was sufficiently well developed to make the distribution of news far more rapid than it had been in the 1790s. Improved rates of literacy went along with a huge increase in the number of urban-industrial workers to provide a ready market for revolutionary ideas. Industrialization and the spread of capitalist institutions, compounding the Continent-wide economic crisis of the late 1840s, meant that distress and discontent impacted on the whole of Europe, not just on relatively isolated areas. Thus the French revolution of 1848 was paralleled by similar upheavals elsewhere.

In Italy trouble started on New Year’s Day in 1848, when the inhabitants of Milan, under Austrian rule, followed the principle of the Boston Tea Party by giving up smoking in order to stop the Austrians obtaining revenue from a tax on tobacco. On 3 January a participant in the boycott knocked a cigar out of the mouth of an Austrian soldier. Scuffles ensued and turned into a full-scale riot. In Sicily the official celebrations of the birthday of the king, Ferdinando Carlo (1810–59), on 12 January 1848 were met by crowds building barricades and flying the Italian tricolour amid cries of ‘Long Live Italy, the Sicilian Constitution and Pius IX!’ Peasants armed with rustic weapons streamed in and braved the grapeshot fired from the garrison at the fortress of Castellamare to drive the troops out of the city. All over Sicily, peasants stormed government offices and burned tax records and land registers. Liberals and democrats joined forces to establish a provisional government and call for elections. Ferdinando Carlo shipped 5,000 troops across to the island, stripping the mainland of its defences. The impoverished slum-dwellers of Naples rose in revolt, inspired by the example of the Sicilians. Terrified of what might happen if no concessions were granted, the liberals organized a demonstration of some 25,000 people in front of the royal palace. The royal troops were persuaded to stand down, and Ferdinando Carlo reluctantly issued a constitution that led to the formation of a moderate liberal government. As the unrest spread northwards, Pope Pius IX, faced with crowds shouting ‘Death to the cardinals!’, promised a part-lay government for the Papal States. Leopold II of Tuscany granted a constitution on 12 February 1848 and Carlo Alberto of Piedmont on 4 March 1848.

Although these events in Italy were already in progress, it was the fall of the July Monarchy that really marked the start of the 1848 revolutions. As the news spread across the Continent, ‘it fell’, in the words of William H. Stiles (1808–65), the American chargé d’affaires in Vienna, ‘like a bomb amid the states and kingdoms of the Continent; and, like reluctant debtors threatened with legal terrors, the various monarchs hastened to pay their subjects the constitutions which they owed them.’ In Mannheim huge crowds led by the radical lawyer Gustav Struve (1805–70) demonstrated in favour of the acceptance by Grand Duke Leopold I (1790–1852) of Baden of a petition he had drawn up, demanding freedom of the press, trial by jury, a militia with elected officers, constitutions for all the German states, and, crucially, elections to be held for an all-German parliament. As the petition was reprinted and circulated across the land, its items becoming known as the ‘March Demands’, constitutions were granted in Baden, Württemberg and Hesse-Nassau; Grand Duke Ludwig II (1777–1848) of Hesse-Darmstadt handed over his office to his son Ludwig III (1806–77) in protest, but a constitution was issued there too. King Ludwig I of Bavaria, already in deep trouble because of his affair with Lola Montez, was forced to grant the March Demands when irate crowds stormed the royal armoury on 4 February 1848, but the situation only calmed down when he agreed to abdicate in favour of his son Maximilian II (1811–64). On 6 March, King Friedrich Augustus II (1797–1854) of Saxony was obliged to enact constitutional reforms and dismiss his conservative chief minister. By 5 March delegates from the newly liberalized states were meeting in Heidelberg to organize a ‘pre-parliament’ that would stage elections for a German constituent assembly.

Events were now moving with dizzying speed. Remarkably, the revolutionary wave now spread across to the Habsburg Empire, which had remained relatively unaffected by the French Revolution of 1789. When the news of the Parisian revolution reached the Hungarian Diet in Pressburg, Kossuth immediately demanded self-rule for Hungary under a reformed Habsburg Monarchy. Copies of the speech circulated in Vienna and students petitioned the government for liberal reforms including the participation of the German areas of the monarchy in a new united German state. Four thousand marched with a petition to the centre of the city and tore up the Estates’ own, very mild petition for changes amid cries of ‘No half measures!’ and ‘Constitution!’ Large numbers of workers armed with their work tools marched in from the suburbs, pulling up lamp posts with which to smash the city gates, which had been prudently closed by the authorities. On the main square, the Ballhausplatz, troops were met with a hail of stones and opened fire. Barricades went up and as the workers finally broke through, alarmed members of the bourgeoisie demanded Metternich’s resignation. On 13 March 1848 the Chancellor finally gave in, announcing his resignation in a lengthy speech of self-justification. He left the city the next day with his third wife in a horse-drawn fiacre and made his way in stages to Brighton, on the south coast of England, consoling himself with the thought that at least his reputation had not been sullied by having been forced to cross the English Channel on the same ship as Lola Montez. Meanwhile, in Vienna, the abolition of censorship and the convening of a constitutional assembly were announced by Emperor Ferdinand I (1793–1875) on 15 March.

The ousting of Metternich, perhaps more than any other event, signalled the profound breadth and depth of the upheaval. He had succeeded, more or less, in keeping the lid on protest and revolution for more than thirty years. Now the lid had been blown off in an explosion of popular rage. There was no going back. Governments everywhere buckled then gave way under the strain. The first to react was Archduke Stefan (1817–67), Palatine (i.e. governor) of Hungary, who had been born in Buda and was generally pro-Hungarian. On hearing the news of Metternich’s downfall he summoned an emergency meeting of the Upper House of the Estates. It agreed to demand a new, liberal constitution. Kossuth, Széchenyi and the liberal reformer Count Lajos Batthyáni (1807–49) travelled by steamboat upstream to Vienna in a delegation of 150 to present their demands. Stefan extracted an Imperial Rescript from Emperor Ferdinand on 17 March 1848, agreeing to an autonomous Hungarian government with Batthyáni as Prime Minister. Kossuth pushed events forward by organizing a twelve-point petition demanding parliamentary sovereignty, trial by jury, the end of serfdom, and the evacuation of all non-Hungarian troops. Swollen by a stream of fresh recruits, a 20,000-strong crowd marched on the Palatine’s castle at Buda, where the troops guarding the Vice-Regal Council melted away and the Council accepted the twelve points in full. In April these were ratified in a lightly amended form by the Diet, making Hungary an autonomous constitutional monarchy, with a widened franchise and parliamentary sovereignty, but still with the Habsburg Emperor as monarch.

The Habsburg Empire was now in serious trouble. As in other parts of Europe, a combination of middle-class discontent, popular desperation, liberal ideologies and revolutionary anger provoked an almost irresistible wave of uprisings that rocked an already nervous and pessimistic civil and military establishment to its foundations. In the Austrian-ruled provinces of northern Italy, the news of Metternich’s fall and the end of royal absolutism in Piedmont spurred the liberals into action. As disorder broke out across Milan, with barricades going up all over the city, paving stones torn up and the vice-governor kidnapped, the commander of the Austrian forces in Italy, Marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz (1766–1858), a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, deployed his troops at key points and stationed snipers on the cathedral spires. Fighting broke out; insurgents clambered onto the rooftops and began firing at Austrian – mostly Croatian and Hungarian – troops below. As his strongholds fell, Radetzky was forced to withdraw, laying siege to Milan from outside. In Piedmont, Cattaneo’s improvised republican administration was pushed aside by the moderates, who persuaded Carlo Alberto to march on the city (he was keen to incorporate it into a new Kingdom of Northern Italy under his rule, and afraid that republicans would overthrow him if he failed to act). While Lombard artisans and farmers rounded up the smaller Austrian garrisons across the land, the Milanese broke Radetzky’s siege in a bloody, five-day battle, and the Austrians withdrew after a last, vengeful bombardment. The victory was symbolized a few days later by the arrival in Milan of none other than Giuseppe Mazzini, ready to take up in person the cause of Italian unity.

The upheavals spread to other parts of Austrian-ruled northern Italy with lightning speed. In Venice, Daniele Manin (1804–57), a liberal nationalist imprisoned by the Austrians for treason the previous year, was released by jubilant crowds as the news of Metternich’s fall reached the city, and immediately organized a citizens’ militia to counter the violence of the occupying Austrian forces, who had opened fire on the crowds on 18 March 1848. On 22 March, at his prompting, workers in the naval dockyards, angered by the Austrian commander’s refusal to give them a pay increase, rose in revolt, beat him to death, and took over the entire area. Manin declared a republic, and the Austrian (mostly Croatian) troops, withdrew rather than damage the city’s beautiful buildings. Habsburg flags were torn down everywhere and thrown into the canals. These events put enormous pressure on Pope Pius IX to join the war against Austria. The Pope sent an armed force to the northern border of the Papal States, where it was joined by 10,000 young Roman men, inflamed by nationalist passion. Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany was forced to contribute 8,000 troops, and King Ferdinando Carlo of Naples reluctantly sent a naval force to break the Austrian blockade of Venice, while a Neapolitan detachment of 14,000 men marched slowly northwards to join the other armies. In late May, 560,000 Milanese voted for incorporation into Piedmont, with fewer than 700 votes against, a result soon replicated in Parma and Modena. On 4 July, brushing aside Manin and the intransigent republicans, the Venetian Constituent Assembly agreed to ‘fusion’ with Piedmont as well. Italian unification suddenly began to look like more than a nationalist dream.

However, the revolutionaries did not have everything their own way. As northern Italy erupted, the violence spilled over into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, where a liberal government forced on King Ferdinando Carlo had formed a citizens’ militia that proved wholly unequal to the task of restoring order. Elections held on 15 May 1848 on a low turnout returned a largely moderate liberal parliament from which Ferdinando Carlo demanded an oath to support the existing constitution. Enraged republicans threw up barricades in Naples, which were assaulted by 12,000 royal troops. In fierce hand-to-hand fighting, 200 soldiers were killed and a larger number of insurgents died as Ferdinando Carlo defeated the rebels. The troops shot many of their prisoners, and extorted money from others, while the urban poor took advantage of the situation to rampage through the city, looting and pillaging amid cries of ‘Long live the King!’ and ‘Death to the Nation!’ Ordered to return to Naples, the Sicilian naval force sent to relieve the Venetians obeyed, along with the bulk of the troops. A minority under General Guglielmo Pepe (1783–1855), a former carbonaro who had fought on Napoleon’s side after the emperor’s escape from Elba, remained, and found their way eventually to Venice to join the forces fighting the Austrians. Yet the republicans had met with a decisive defeat. Worse was to come. Radetzky was told by the government in Vienna ‘to end the costly war in Italy’, but he refused to negotiate. He was encouraged behind the scenes by hardliners in Vienna, led by Count Theodor Franz Baillet von Latour (1780–1848), Minister of War, a soldier descended from a Walloon family in the former Austrian Netherlands. Radetzky advanced his 33,000 troops against Carlo Alberto’s 22,000 at Custoza, a small hill town near Verona. On 24 and 25 July 1848 the Austrian troops drove the Piedmontese down the hill in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. It was the end of Carlo Alberto’s attempt to unite northern Italy. He was forced to sign an armistice. ‘The city of Milan is ours,’ Radetzky crowed: ‘no enemy remains on Lombard soil.’ Mazzini took a different view. ‘The royal war is over,’ he declared in a proclamation issued in August 1848: ‘The war of the people begins.’

Much still depended on what happened in Vienna. Here, events had been moving fast since the fall of Metternich on 13 March 1848. Four days later a constitutional ministry was formed, the imperial police force was restructured, and police spies were dismissed. Food taxes were lowered, a political amnesty was declared, and job-creation schemes were established. But the granting of a constitution by Ferdinand on 25 April outraged the radical democrats, because it still reserved decisive powers to the emperor. By 4 May mass demonstrations, joined by many workers, had forced the head of the new government to resign. When a restricted franchise was announced on 11 May, the radicals’ anger knew no bounds. Impatiently pushing forward the demand for the election by universal male suffrage of a democratic constitutional assembly, the students formed an Academic Legion that soon numbered 5,000 men, while the moderate liberals’ militia, the National Guard, counted 7,000 in its ranks. On the night of 14–15 May 1848, led by the students, a massive crowd marched on the royal residence to demand the revision of the constitution and the immediate holding of democratic elections. Ferdinand and his entourage panicked and gave in. The Cabinet resigned in protest. Two days later the emperor and his family left Vienna at night for Innsbruck. The parallel with Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette’s ill-fated flight to Varennes was lost on no one.

Safely away from the capital, Ferdinand issued a proclamation condemning the actions of an ‘anarchical faction’ and calling for resistance; or rather, it was issued for him, since, though not unintelligent, he was incapable of ruling. He had a severe speech impediment, and suffered up to twenty epileptic fits a day (he had five when he tried to consummate his marriage, and not surprisingly, had no children). One of his few known coherent remarks was a reply to his cook, who had told him that he could not have apricot dumplings because apricots were out of season: ‘I’m the Emperor,’ Ferdinand was said to have replied, ‘and I want dumplings!’ On 24 May 1848 his advisers closed the university in Vienna, then, the next day, they ordered the disarming and disbanding of the Academic Legion. But the National Guard went over to the side of the students, while hundreds of workers descended on the city centre. Tearing up paving stones and carrying furniture out of the houses, the students put up 160 barricades at key points, some of them rising up to the second floor of the houses on either side of the street and topped by red and black flags. The government forces were too weak to assert themselves, and were withdrawn, while Ferdinand and his entourage acceded on 12 August to the students’ demands for his return. Driving from the quayside at Nussdorf to the centre of the city in an open carriage, he was greeted with hisses mingled with barely audible shouts of welcome from the crowds lining the streets. The emperor ‘stared at his knees’, as an observer reported, while ‘the Empress had evidently been weeping’. The serried ranks of the National Guard let them pass without a salute, and the band of the Academic Legion played Arndt’s What is the German’s Fatherland as they passed, instead of the Austrian national anthem. The democrats in Vienna had, for the moment at least, gained the upper hand.

What happened in Vienna was closely bound up with what happened in the rest of the German Confederation, where one state after another had been forced to grant a constitution with full parliamentary rights. The pressure on the largest of the member states, Prussia, was growing daily. On 16 March 1848, when news of Metternich’s fall reached Berlin, panic broke out in the ruling clique. While Friedrich Wilhelm IV’s adjutant-general, Leopold von Gerlach (1790–1861), and the king’s brother and heir, Prince Wilhelm (1797–1888), urged the use of force, the king decided to make concessions, announcing the abolition of censorship and the summoning of the United Diet, in abeyance since the previous year. It would consider strengthening the German Confederation with a national law code, a flag and a navy. But this was not enough. As the demonstrators shouted for the troops to be withdrawn, shots were fired, and soon barricades were going up all over the city and men began to sound the tocsin on the bells of the city churches. On 18 March the Prussian troops mounted a full-frontal attack on the barricades with infantry and artillery, and soon, as an eyewitness reported, the streets were running with blood. By the end of the day 800 demonstrators, the vast majority of them impoverished artisans and unskilled workers, members of the new working class, were dead.

Rather than spelling the end of the revolution, however, the March events only drove it on. The king had not sanctioned the use of firearms, and was appalled by the bloodshed. On 19 March, as crowds bearing the bodies of many of those killed the previous day broke into the Palace yard, demanding to see the king, Friedrich Wilhelm appeared, ‘white and trembling’, and removed his hat amid mocking shouts from the crowd. The scene inevitably reminded people of the crowds that had stormed the royal palace in France in 1789 and forced Louis XVI to bow to their will. ‘Now only the guillotine is left,’ the queen is said to have remarked. But the king’s gesture restored calm. Two days later Friedrich Wilhelm gained further popularity by riding through the streets wearing the German national colours of black, red and gold, and accompanied by numerous officers bedecked in the same insignia. On 22 March he was forced to attend the elaborate funeral of the victims of four days before, again removing his helmet in a gesture of reverence to the dead and submission to the masses. Friedrich Wilhelm gained huge popularity by these gestures; privately, however, he experienced them as a deep humiliation. Towards the end of the month he ordered his troops to withdraw from Berlin, against further protests from the hardliners in his entourage. The city was now in the hands of the revolutionaries.

At this point, however, serious divisions began to open up between the moderate liberals and the hard-line democrats. In the Prussian Diet, elected by indirect though ultimately universal adult male suffrage, the conservatives mustered 120 delegates out of 395, enough to block the policies of the moderate liberal, Gottfried Camphausen (1803–90), a banker appointed head of the Council of State on 29 March 1848. On 14 June violence broke out in Berlin when democratic demonstrators, including many workers carrying red flags, looted the royal armoury. Helpless in the face of continued disorder, Camphausen resigned on 20 June. The diehards were thoroughly alarmed by the Diet’s presentation on 26 July of a draft constitution removing virtually all power from the king and the army and abolishing all aristocratic titles. On 9 August the deputies demanded that all soldiers should swear an oath of loyalty not to the king but to the constitution. As Camphausen was followed by a succession of weak ministers, the outraged monarch began making plans with Gerlach and the conservatives to take back the initiative. Similar cleavages soon became apparent in the national pre-parliament that met at Mannheim on 31 March 1848, in this case between moderate liberal deputies such as Heinrich von Gagern, who envisioned a united Germany as a federation of monarchies, and radical democrats such as Gustav Struve and Friedrich Hecker (1811–81), both from Baden, who demanded a single unitary German republic and the abolition of the existing German states along with their sovereigns. Outvoted in the pre-parliament, the two democratic leaders proclaimed a republic on 12 April 1848, and began raising an army. They were joined by a band of German emigrants from Paris under the leadership of the radical poet Georg Herwegh (1817–75), but they were no match for the 30,000 disciplined and well-armed troops mustered in Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria by the German Confederation, who defeated them at Kandern on 20 April and in a few subsequent minor skirmishes.