Gosford was a sleepy estuary town on Brisbane Water north of Sydney with pretensions of being a regional centre. The pubs and public buildings gave the place an air of possible permanence but the houses that hugged the surrounding hills were sad boxes of fibro, weatherboard, tin and peeling paint. The smell of salt water and dead fish saturated everything.

This was the last place Gribble wanted to be. He had been filling in time with occasional deputation work and praying for a new mission when the ABM broke the news, in 1911, that it would not support him any longer. Christ Church, Gosford needed a priest and Gribble needed work. The only saving grace in this shotgun marriage was that Gribble managed to convince Amelia to bury the hatchet for a while and try to revive their marriage. The notion of playing rector’s wife dispensing sedate afternoon teas in the rectory caught Amelia’s fancy but the experiment failed on all fronts. The reunion was strained and disagreeable, and Gribble loathed parish work.

He escaped the depressing pallor of his new existence by pouring his energies into writing. It was a cathartic distraction. His first autobiography, The Life and Experiences of an Australian, was completed during this phase and serialised by the Gosford Times in 1915. It drew on a collage of vignettes that had lain buried since childhood: the idyllic years at Warangesda; the invigorating spell at the Kings School; and snapshots of religious ambivalence among the selectors of Tumbarumba. These fragments of memory resurrected a happier life than his present existence. In between scribbling, Gribble ferreted out any chance to return to the bush and missionary life. Word filtered through that Bishop Gerard Trower, the new, reluctantly-appointed head of the North West diocese, was establishing a mission in the remote north of Western Australia. Gribble instantly offered his services. He was an experienced bush missionary, he told the Bishop, who could rescue the venture if the staff failed to perform.

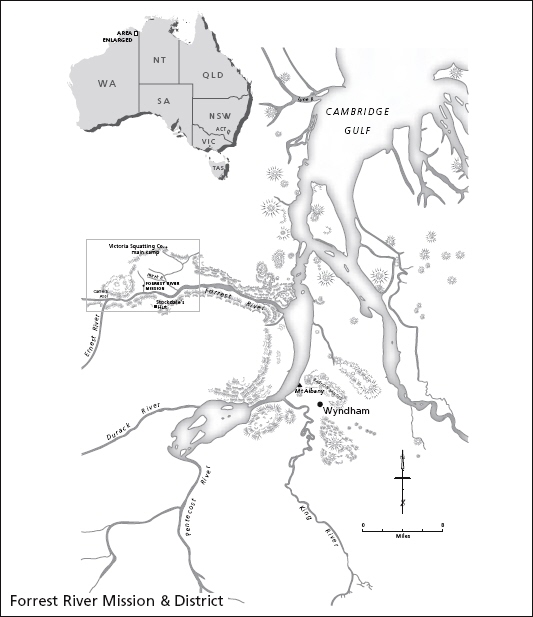

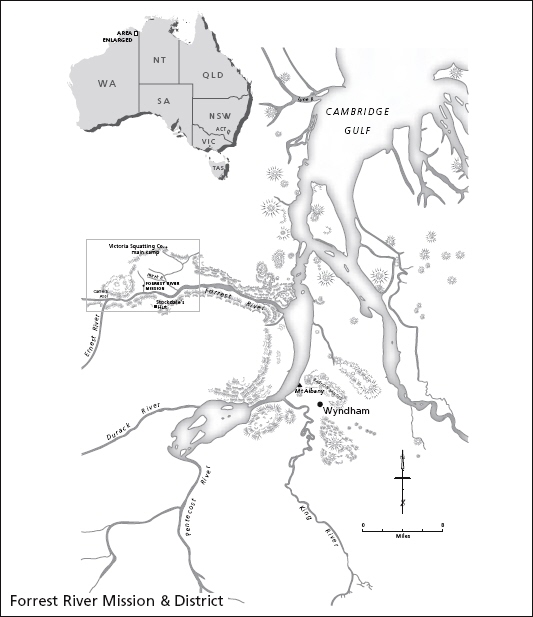

Trower summoned him six months later. Gribble left Gosford within the fortnight. He stepped off the government steamer onto the wharf of the remote township of Wyndham, in the east Kimberley, on 30 December 1913. Two days later he welcomed in the New Year by resigning his parish in Gosford. He had not seen his new mission but the work was a ‘path of duty’ and his vision was clear.1 Forrest River would be Yarrabah without the poisonous blemishes of those final years where he would realise the hopes and dreams of JB’s struggle in Western Australia 30 years earlier.

Wyndham lies on the western side of the Cambridge Gulf, half a continent and a whole world away from the State capital of Perth. The town was named after the second son of the first marriage of Lady Mary Ann Broome (1831–1911), wife of the irascible Governor Sir Frederick Napier Broome, whose wild feuds with public officials nearly eclipsed his administration’s triumph at securing responsible government for the colony. The town’s namesake, Walter George Wyndham, fought with Lord Chelmsford in the Zulu wars in Africa. The Australian township that inherited his name lay in an equally alien, frontier region on the periphery of British civilisation.

Wyndham had developed capriciously by sprawling laterally along the waterline to hug the slim strip of ground between the tidal mud flats of the Gulf and the rocky slopes of Mt Albany and the Bastion Ranges. In the 1920s, the town was a barren clutch of square, white houses clustered around a labyrinth of dirt tracks pounded hard by the hooves of horses and cattle that transformed into a brown quagmire during the summer wet season. Sterile, gnarled mountains guarded the hazardous, crocodile-infested Cambridge Gulf and its rushing 30-foot tides and the heat was so blistering that locals were said to ‘feed their fowls on chipped ice to keep them from laying fried eggs’.2 This was an unforgiving place that God had forgotten—a lair for the fearless, the foolhardy and the misfit.

Forty years after its first exploration by Lieutenant George Grey, Alexander Forrest traversed the region naming it the Kimberley district and praising its grazing potential. Within three years, cattle dynasties like the Buchanans, Duracks and Macdonalds from Queensland and New South Wales had invaded and taken up most of the best land. Gold attracted thousands of hopefuls to Halls Creek in the south east and, by 1887, Wyndham was a flourishing centre boasting six hotels. Champagne flowed freely and business was done with gold nuggets.

The boom was over by 1890. Most of the diggers had left for more promising strikes in the south and the fledgling cattle industry was floundering. Only the most serious pastoralists stayed. Cattle tick stopped livestock exports between 1896 and 1899 and again in 1911 when buffalo fly and pleuro-pneumonia forced cattle owners into costly immunisation programs. A government meat-works was built in 1919 but high operating costs caused its closure in 1921. It reopened twelve months later but hardly ever broke even. The town struggled. Cash was so scarce that shopkeepers and publicans issued promissory notes redeemable at the bank that were notorious for their convenient tendency to disintegrate when handled. On the eve of World War I, there were fewer than 200 Europeans in the East Kimberley and the population of Wyndham had stagnated at around 50. It hovered there for the next decade.

The Forrest River Mission lay on the western side of the Cambridge Gulf about 50 miles up the Forrest River from Wyndham, in the middle of the vast Marndoc Aboriginal Reserve. It occupied the stretch of flat land between Dadaway Lagoon and a line of rugged, stony hills that led to a gallery of sacred Aboriginal burial caves and the fresh waters of Camera Pool on the edge of the Oombulgurri Plain. The Western Australian Government proclaimed the 3 000 000-acre reserve in 1911. It stretched across the majestic Kimberley ranges as far as the Cambridge Gulf to the east and the coast to the north, and spread south through the Milligan Ranges and across the Durack River to Bindcola Creek.

In 1898, the Church swapped the site of JB’s failed Gascoyne River mission for the 100 000-acre lease in the Marndoc Reserve. The historical symmetry appealed to Gribble. The mission lease spread across both sides of the mighty Forrest River and the red sandstone cliffs that guarded the river as it wove through the rugged hills and sterile, stony flats of the Kimberley ranges. Downstream the river was bracken with the cloying salt of the Cambridge Gulf. Upstream it melted into ponds ringed by pandanus palms and filled with sweet, fresh water and lilies. A menagerie of catfish, barramundi, cockatoos, ducks, brolgas and hungry crocodiles flourished around the river, but the surrounding country was occupied by scrub, spinifex, kangaroos and termite nests that transformed the stony plains into an eerie landscape of gnarled, red mountains. It was a heartless, unwelcoming land. The first European visitor described Siberia as more hospitable.

This was Yeidji territory. Their custodianship of the land stretched north from the Forrest River to the sea coast of the Cambridge Gulf as far as the Milligan Ranges, south to the Steere Hills and north to Mount Carty and the Lyne River. The Yeidji had close ties with the Wembra to the west and the Arnga whose territory lay to the south along the King and Pentecost Rivers. They also had links with other Kimberley groups including the Bemba, to the north west beyond the Forrest River, the Yura, to the east of the mission along the coast of the Cambridge Gulf between the Patrick and lower Lyne Rivers, as well as the Baragala, an Arnga group, to the south east of the mission. People from further afield like the Kwini from the Drysdale River and the Wunumbul from the west of King Edward River had regular contact with the people of the district.

The Aboriginal communities of the Kimberley shared similar language and a rich mythological tradition dominated by three powerful Dreaming figures: Wandjina, a regenerative, reproductive power linked with rain and water; Brimurer, the Rainbow Serpent who created the rivers and sent forth spirit-children; and Wolara, who instituted initiation, increase ceremonies and other features of social life. Wunan (trade routes) crisscrossed the Kimberley and linked the material life of the communities through the exchange of red ochre, iron axes, boomerangs, shovel and wire spears, wooden water carriers, karl (spinifex resin) and the powder from burnt gypsum used to make ceremonial body paint. Almost every food in the region was linked with a talu (increase) site and an associated ceremony. At key times during the year, the different communities converged to harvest seasonal fruits like gelay (plum) or to conduct initiation rites and mourning ceremonies, renew kinship and political allegiances, and exchange corroborees, mythology, rituals and Law. In this harsh dry land, gatherings usually converged on a waterhole. These gra (sacred sites) were the homes of the spirit-children that took the animal forms hunted by man. Every person was the embodiment of a spirit-child linked with a specific water source where they were ‘found’ by their father and generally named after their spirit centre.

The Kimberley peoples exploited imported European technology by making spear heads from glass and metal instead of stone. The results were deadly and devastating. In 1895, the Ord River Station claimed Aboriginals killed stock valued at £20 000. Two years later, the district reported stock losses of £134 000. The Aboriginals used their superior knowledge of the country to evade capture and launch attacks during the wet season when flooded plains made pursuit impossible. Cattle and sheep polluted and desecrated sacred sites and waterholes, and Aboriginals often slaughtered more than they could eat. Some pastoralists believed they killed cattle for sport.

Police stations sprang up at Wyndham, Halls Creek and Turkey Creek to protect settlers and property. From 1892, cattle killing became an offence punishable with three years’ imprisonment and a beating with a cat-o-nine-tails. The police got two shillings for the capture and conviction of a cattle killer but these drastic measures had minimal effect. In 1909, the government established Moola Bulla cattle station in the hope that distributing meat to Aboriginals would reduce attacks on private herds.

This was a world where settlers felt isolated and outnumbered. The exploits of Aboriginal warriors like Pigeon and Major fuelled fears of a wholesale black uprising and settlers were united by a siege mentality and the belief that ruthless action was needed to secure the region and their protection. A catalogue of Europeans died in the battle to possess the Kimberley. The inventory for 1886 included Fred Marriot, who lost his life during an Aboriginal attack on the Halls Creek goldfields; John Durack, who was ambushed and speared; and another digger killed near Mt Barrett. In 1888, William Miller died after being attacked near Mt Dockrell and a teamster was killed near Wyndham. In 1896, Frank Hann and Ah Sing, a market gardener on the King River south of Wyndham, were killed. In 1901, Aboriginals shot Jerry Durack through the head while he was sleeping. His son Patsy was wounded.

Settlers formed vigilante groups and the police used armed Aboriginal trackers and deputised civilians to hunt suspected murderers but punitive action was often the underlying aim, as one letter writer explained after diggers were killed at Mt Barrett:

A number of diggers went out to take revenge. Having bailed up a large number of blacks in a gully who showed fight, they proceeded to slaughter them with repeating rifles. It is certain that a great many were killed, some say at least a hundred.3

It was widely accepted that ‘a war of extermination, in effect, is being waged against these unfortunate blacks in the Kimberley district’.4 Francis Connor, Member of the Legislative Assembly and partner in the Durack cattle dynasty, led an unsuccessful campaign to establish a Native Police Force to suppress black resistance: ‘It is simply a question of whether we or they are to have this country’.5

It is impossible to estimate the number of Aboriginals killed in the struggle for the Kimberley. Settlers and police united in a code of silence. It took two years for Police Constable Ritchie to learn of a massacre near Jerry Durack’s station on the Denham River. Richie found the incinerated bones of the bodies on the property but his efforts to prosecute Durack were blocked.

In 1884, Harry Stockdale led the first European foray onto the western side of the Cambridge Gulf near the future site of Gribble’s mission. One of the party, J.H. Ricketson, was attacked when he rode into an Aboriginal camp and had to be rescued by Stockdale who shot one of the ringleaders. A few weeks later an old Aboriginal man blocked the party’s path as it skirted around a billabong. Ricketson killed him with a single shot at point blank range. Ricketson declared the area inhabited by hostile Aboriginals but Stockdale returned a year later to manage a 100 000-acre lease taken up by the Victoria Pastoral Company. Two thousand sheep were herded to Gundah Creek on the Patrick River near Mar-ri-da, a sacred talu site for fish and lily-root for the Yeidji and Wembra. Several talu sites and at least five significant sacred sites were within a five-mile radius of Dadaway Lagoon, including a stone Djalmula that was said to have been put there in the Dreaming after the crane and policeman bird fought and the crane threw the fire sticks that gave the policeman bird red legs. The Aboriginals defended their sacred sites forcing Stockdale and his party to withdraw to Dadaway Lagoon. Among the group was Mrs Wilkes who gave birth to the Kimberley’s first European child in 1887.

In 1889, the vigorous Aboriginal resistance forced the Victoria Pastoral Company to withdraw but in 1898, Harold Hale, son of the first Bishop of Perth, led a five-man party to establish an Anglican mission on the Forrest River. The Government Resident in Wyndham warned Hale that the Aboriginals were dangerous, but his caution was ignored and the group set up at the abandoned Stockdale homestead at Dadaway Lagoon. Aboriginals stole their food and supplies and a large, threatening assembly eventually congregated around the mission. Hale was injured by a glass-tipped spearhead that caught him in the arm and ripped the muscles so badly that he needed urgent medical attention. Another member of the party, Sidney Hadley, was speared in the shoulder and the mission lugger was untied to drift down river.

A visiting police patrol helped Hale capture the culprits by enticing them into the cottage where they were overpowered before being taken to Wyndham for trial. All five offenders received fifteen lashes. Hale’s attackers were imprisoned for two to three years and the boat thieves received prison terms of three to six months. The incident was ‘unpropitious’, warned the Western Australian Record in February 1899, and ‘may . . . adversely affect the disposition of the local blacks’. Thereafter, the attacks intensified. One of Hale’s party was clubbed unconscious and lay in a coma for three days, the mission boat was disabled and the party resorted to firing shots into the air to disperse their attackers. It was suicidal to stay, warned the Resident Magistrate in Wyndham. The Police Commissioner urged the Church to withdraw before lives were sacrificed. The mission was abandoned at the end of 1898.

In April 1913, Bishop Gerald Trower led a six-man party in a second attempt to establish a mission in the Kimberley near the site abandoned by the Victoria Pastoral Company and Harold Hale. Trower christened the mission ‘St Michael and All Angels’ but the early omens were ominous. A young naturalist with the group called Burns got tangled in lily-roots while duck shooting and drowned. Trower returned to Broome and the missionaries erected a small prefabricated tin hut to serve as a church, sleeping quarters and storeroom. They reinforced the walls with stones and surrounded the compound with looped, barbed wire, but it did not protect them. One of the lay missionaries was clubbed unconscious and Aboriginals looted the mission boat and raided the compound at night. The missionaries resorted to firing shots into the dark to stop a full-blown assault and, by September 1913, the frayed and terrified staff had all resigned. Reverend Stubbs was summoned from Port Hedland to hold the fort until Gribble arrived.

Knowing he would need help, Gribble’s first act was to wire James and Angelina Noble. They already had four years as lay missionaries at the Roper River Mission in the Northern Territory, and Church officials nodded approvingly when the Nobles arrived in April 1914:

The fact that these fellow country-men of the same color [sic], have come from afar to lead them to the same calling and teach them the same Creed as they themselves have long embraced, must appeal strongly to the native mind.6

Angelina Noble’s delicate features and dainty figure hid her tough disposition. She was a crack shot, talented linguist, expert rider and absolutely fearless. A horse dealer had abducted her when she was a young girl, dressed her in boy’s clothing and passed her off as ‘Tommy’, but her disguise was eventually detected and she was sent to Yarrabah where she married James Noble when she was sixteen. For five years Angelina was the only woman at Forrest River Mission. Her husband, James Noble, was one of those men with that enviable but intangible quality known as ‘presence’. At 6 feet tall, he towered over his petite wife. His dark, gentle eyes were set above uncommonly high cheekbones and a clean, square jaw. It was the open face of an honest man. Although originally from the Normanton district of Queensland, Noble was reared by the Doyle family of Scone in rural New South Wales from the time he was about ten and tutored at Scone Grammar School. Later, he lived with Canon Edwards in Hughenden, north Queensland, where his talent as a sprinter made him a minor celebrity. When the Canon died James fell in with a bad crowd and the Bishop of north Queensland stepped in and sent the 16-year-old to Yarrabah, where he became one of Gribble’s proteges. His calm resourcefulness made James a capable, congenial manager and he freed Gribble of the burden of supervising Yarrabah’s out-stations. He was just shy of 40 and his wiry, dark hair was already grey when he joined Gribble at Forrest River in 1914.

Gribble drew on Angelina’s talents as a translator and James was barber, dentist, doctor and general hand. James’ abilities earned him respect. He was treated like an Elder and the people listened when he spoke. In Church circles, the Nobles were credited with thwarting the attacks that had sent other missionaries scurrying from Dadaway. Their daughter, Lovie Kianna, grew up on stories of how her parents pacified the hostile people around Forrest River:

The river [was] just black with Aboriginals [who were] just watching them. Wild people . . . They didn’t want to see those white people cause they never saw white people in all their lives. Then [James] got up and stood at the fore of that boat. When they saw him they all put their spears down. That was that and they were all calm when they saw this . . . black man and he told them ‘my wife is black too but she’s half-caste’ . . . They were satisfied with the wife too . . . and they all put down their spears.7

James’ particular contribution was acknowledged in 1925 with his ordination as the Anglican Church’s first Aboriginal deacon.

Lured by medicine and tobacco, Gribble’s mission soon became a marshalling point for Aboriginal groups from across the Kimberley. By 1914, about 200 people camped around the lagoon and on the rocky ridge behind the mission. Hundreds of others visited as they travelled the wunan and, during these early years, Gribble carefully recorded the names of those that came and went. His medicine treated a cavalcade of sick—2067 in 1923— and his tobacco was the currency that purchased labour to clear the land, build and plant crops. The availability of tobacco and the precious glass and metal debris needed for spearheads made Dadaway Lagoon a terminus for the Kimberley wunan trade.

Gribble divided the people into three classes. The brengen lived in semi-permanent camps near the mission and occasionally worked for food and tobacco but came and went as they pleased. The narlies visited off and on to trade in tobacco and join festivities as they travelled to tribal rituals and seasonal supplies of native food. As far as Gribble was concerned, the ‘inmates’ in the mission compound were the mission, but the children were his primary focus. Gribble started a school with a small clutch of boys using red ink and boot polish to write lessons on galvanised iron. By September 1914, dormitories were built and surrounded by a 3-foot-high fence topped by two strands of barbed wire. Only his mission, Gribble believed, could provide temporal and spiritual salvation. He refused work, and therefore food and tobacco, to parents who would not hand over their children, and collected waifs from Wyndham and the bush. Anxious to build numbers, mission inmates remember Gribble bribing Aboriginals to abduct ‘kids from the bush for the school and dormitory’.8 Many parents avoided the mission because they knew:

once [a] child is in the Mission, he or she will not be allowed out again except for a few hours on a holiday under the supervision of a missionary, that later the child will be married contrary to the tribal laws and to promises made by the parents and that finally, the child becomes a complete outsider to all tribal culture.9

Gribble reported in the Church press that the mission had a wonderful hold on the local people. In reality, life was hard. Aboriginals stole petrol and food; floods regularly washed away the mission jetty; crocodiles ate the dogs that were Gribble’s companions; and supplies from Perth were erratic especially during World War I when strikes and the withdrawal of steamers caused serious shortages. Gribble planted vegetables, maize and millet for the mission, watermelons for sale in Wyndham and peanuts for the Adelaide market, but the results were unreliable in a fickle world of floods, droughts and plagues of ticks, locusts and grasshoppers. Sometimes there was no food for weeks and potential converts were turned away and inmates sent out to collect ‘native tucker’. Meanwhile, Wyndham’s shopkeepers grew fat selling goods at inflated prices to the anxious missionary desperate to keep a hold on his ambivalent flock. Just as at Yarrabah, reciprocity defined local social relations. Without food or tobacco, the people refused to work and disappeared into the bush or went to Wyndham for sugar, tea and flour. The people called Gribble Judja, meaning ‘boss’, but when native fruits were ripe and plentiful, only a few children and old folk remained in the mission and Gribble repeatedly reminded the faithful that the ‘primary object of getting their souls is lost, if we have not got their bodies’.10

The problem, Gribble complained, was that he was shorthanded. He put on a boatman-cum-cook called Rackarock who seemed capable enough but he was known to police across north Australia and his addiction to ‘black velvet’ caused trouble at Dadaway. Eighteen months after being sacked from the mission, Rackarock was imprisoned for raping a young Aboriginal girl in Wyndham. His replacement turned out to be a drunkard who polished off the mission’s supply of altar wine. Others came and went just as quickly for it was hard to survive Gribble’s tantrums and hurtful tongue. Part of the problem was that he played favourites, but his fancies were unpredictable and changed without warning. He made life miserable for those who fell from grace. One staff member—a devout spinster Gribble branded ‘a nag’—was so distressed by his attacks that she packed her bags and returned to Perth. Gribble was always contrite and full of self-loathing later, but then it was generally too late. By September 1915, all his staff had left or were leaving.

According to the mission register, by 1916 there were 40 inmates living in the mission compound, but most were children, elderly, sick or maimed. Gribble was frustrated by the slow progress. His dream of replicating Yarrabah at Forrest River seemed to be elusive, and an unsettling sense of doom descended. He remembered the other times he had experienced the same disquieting feeling: when JB abandoned him in Carnarvon; during his ill-fated involvement with Fraser Island; and throughout those stressful, final years at Yarrabah.

His distraction was to declare war. The continued exploitation and abuse of Aboriginals in the north west deeply offended his keen sense of justice. He could see little evidence that conditions had improved since his father’s campaign against police and pastoralists in the 1880s. As his moral outrage conflated with his disappointment in the mission’s progress, he threw himself into a new role as the moral champion of Aboriginals in their dealings with whites. In 1915, he bailed up a stockman travelling with two Aboriginals and demanded to see the Chief Protector’s authority to take them from their district. When the documents were not forthcoming, Gribble asserted his authority as Protector of Aborigines and took the pair to his mission. Local settlers were outraged and protested that their livelihood hinged on unfettered access to cheap, black labour, but their opposition did not intimidate Gribble. He went further and banned mission inmates from working on the roads in Wyndham. Settlers accused him of keeping ‘young bucks’ idle and poaching workers to increase the numbers at his mission. The Chief Protector of Aborigines, Auber Octavius Neville, sided with the settlers. Neville, an impeccably groomed bureaucrat with a round face and close-set eyes, inhabited the government offices in Murray Street Perth and was called ‘Mister Neville’ by the State’s Aboriginal population. Gribble did not care that the Chief Protector believed in the gainful employment of able-bodied Aboriginals. His position was firm. The only hope for Aboriginals, Gribble argued, was total segregation under missionary influence and he was:

determined to fight against any of our Aborigines going into Wyndham [because] it . . . means prostitution for the females and a lazy life for the husbands and apart from that we must urge & work for segregation if we are to do any good.11

He harassed the Chief Protector and Sergeant Archie Buckland, Wyndham’s senior police officer, to invoke Section 39 of the 1905 Aborigines Act. Introduced in the wake of the Roth Royal Commission, the Act gave the government sweeping controls Forrest River Mission & District over Aboriginals, including the power for the police to exclude Aboriginals from prohibited areas and to remove unemployed Aboriginals to reserves. Gribble hoped that the declaration of Wyndham as a prohibited area would stop Aboriginals being ‘drawn off the Reserve and away from [mission] influence’.12 Sergeant Buckland took a different view. He had been subduing Aboriginals in the Kimberley since the 1890s and he knew the desires of settlers and pastoralists. A zealous missionary would not rouse him to act against their interests. Gribble responded by launching an eighteen-month campaign in Church journals and The West Australian, accusing Buckland and the police of being lax and ignoring his complaints. Gribble’s campaign alienated him from the sympathies of settlers and police in the north west, but the prohibited area was declared in 1916.

Word that Gribble was making trouble began filtering south and the Perth Board of Missions started to get anxious. It handled the daily administration of Forrest River for the ABM in Sydney and Gribble’s crusade against the police revived its collective memory of JB’s clash with the establishment and the upheaval that resulted. Just as troubling for the Secretary of the Perth Board of Missions, Archdeacon Hudleston, was the high turnover in staff and the mission’s mounting debts to shopkeepers in Wyndham. Hudleston decided to make the long trip north to personally inspect the mission. On his return to Perth he floated the idea of replacing Gribble but Bishop Trower rejected the idea outright. This path blocked, Hudleston urged Gribble to take an early furlough rather than wait the usual five years. Gribble’s past flashed before him. His confidence was rattled. He insisted that he was indispensable and doing the work of three men: ‘to force matters as regards my furlough will not do’.13

Gribble exhausted his anxiety by forging a tidy village between Dadaway lagoon and the stony hills that edged Oombulgurri Plain. Streets were laid out in grid formation and named after Anglican missions. A hospital, dormitories and married people’s home appeared. The Church of St Michael and All Angels—a thatched pavilion partially open on all four sides—was the only church in the East Kimberley when it was completed in 1921. The thatch buildings were picturesque, but alive with nesting insects and fires were frequent. To keep the dust at bay, the dirt floors were soaked with bullock blood and polished to a shine when dry. The furniture was ‘Kimberley Chippendale’—rough constructions made from onion and oil boxes. Later the place was rebuilt in sun-dried bricks. Michael Durack, patriarch of the Durack cattle dynasty and Member of the Legislative Assembly for the Kimberley from 1917 to 1924, visited the mission and declared it a collection of ‘tumbledown sorts of thatched houses’.14

Gribble put his hopes for a Christian community in the young married couples in the mission compound. Women were persuaded to abandon their tribal husbands and married on the mission in defiance of betrothal commitments, kinship laws and tribal obligations. The brengen and narlies retaliated by showering the compound with spears when Gribble refused to hand over married women or girls promised as brides. The women at the mission had to be guarded in case they were abducted or absconded, and the men were attacked for ‘marrying wrong’. Gribble threatened the attackers with twenty strokes of his strap and promised to ‘drive back with a stockwhip any mission man who went outside the compound to the old men’s camps’.15

Outside the mission compound, the birth rate fell. Gribble declared this a victory for God and proof that the mission was saving the local people from extinction, but the women told anthropologist Phyllis Kaberry that they aborted pregnancies because they did not want to bear children to be taken by the mission. Others avoided the place. Inside the compound, Gribble worked to impose order. Inmates mastered daily drill, the children marched to and from church in straight lines singing the ‘Gloria Patra’ and the school day ended with a chorus of ‘God Save the Queen’. Gribble fell back on the familiar formulae he had used at Yarrabah: bells summoned everyone to daily parade for the allocation of jobs; the mission population gathered to salute the Union Jack on ‘Flag Day’ each month; and Sunday mass was proceeded by a procession through the village to strains of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’. Services were intoned with sung canticles, scarlet-clad choristers sang Holy Communion and Compline, and the return of the mission boat was greeted with a chorus of ‘Te Deum’. Gribble reported that the local people were curious about God and listened attentively during services. His favourite text was ‘Mission boy no tell lie; no steal, no lazy fellow, no dirty fellow’.16 In mid-1915, he began a class with seven Catechumens. Twelve months later, four inmates were baptised, although the first confirmation was not held until six years later, in August 1922. By the end of 1928, the tally of converts was 134 baptisms and 34 confirmations, but Gribble admitted that most baptised men left after a few months to find wives. Four confirmed men (11 per cent of the total) absconded to fulfil traditional marriage obligations and Gribble deposed his five most trusted converts from their posts as church servers after they participated in circumcision rites. Reverend Haining arrived at the mission and summed up the situation succinctly: most converts eventually ‘lapse and go bush’; Christianity is ‘not as real as one could wish [and] does not seem to have sunk in very deeply’ and is ‘based upon a superstitious fear & [sic] a large percentage of hysteria’.17

Meanwhile, Church publications spread the news that girls from the dormitory pulled the punkah while the staff ate their meals and the inmates were always:

quick to show their gratitude, never forward in their behaviour towards the missionaries, and a black always humbly walks behind a white person . . . the poor blacks . . . understand that the Mission is here . . . solely for their good and happiness . . . three or four years ago, vice, in some of its vilest forms, reigned supreme [now] the Mission boys and girls . . . have a repugnance for the same evils that in the early days they looked upon as quite a matter of course . . .

cleanliness is gripping them . . . the Mission is their home . . . when spoken to, the Mission blacks reply ‘Yes, Sir’ or ‘No, Sir’ and salute.18

Yet the mission population stagnated. Inside the compound Christianity supplanted tribal and totemic identities and English replaced ‘language’. It was impossible to keep the precepts laid down by the ancestor heroes to sustain the cosmos and the continuity of the Dreaming. Gribble banned infant betrothals, polygamy and traditional mortuary rites, and threatened to horsewhip anyone participating in initiation rites or revenging violations of marriage laws. Increase ceremonies could not take place or sacred sites be maintained and deferred mourning ceremonies could not be performed to enable the zuari (spirit) of the dead to rest in peace. Boys were not initiated into the Law or dara:gu (sacred ceremonies), and it was difficult to preserve ramba (marriage avoidance) or for the women to keep pregnancy taboos or be isolated during their menses when it was believed they could make a man ill by touching his belongings.

Gribble and James Noble spent fruitless days pursuing those who fled the mission to return to a more culturally familiar world. Gribble begged the Wyndham police for help but Sergeant Buckland claimed Aboriginals said they would rather go to Roebourne gaol than return to the mission. Desperate and worried, Gribble intensified repression in the compound. Recalcitrant inmates were tried in a public court but there was little resemblance to a local djaruk (people’s court) for Gribble decided the verdicts: ‘he was a very, very strict man’.19 Children who fled or were cheeky had a sign of the cross shaved through their hair. Others had to repent in public and Gribble’s leather strap—‘Black Tom’—got frequent use. Young boys tried to dodge the pain by stuffing sheepskin down their pants. Adults were imprisoned in the stone gaol or publicly handcuffed to a post, and when Ronald stole meat from the store:

all the mission had to line up and watch as a lesson . . . he was tied around a boab tree, facing the tree and standing and given four cuts with Black Tom like a slave.20

The answer, Gribble decided, was to use the 1905 Act and make Forrest River a depository for children, the ill and the elderly. From 1921, the mission was ‘home’ for about 37 pensioners each year and a generation of Stolen Children transported from Broome, Derby, Port Hedland, the Oscar and Leopold Ranges. By 1928, there were 111 Aboriginal inmates at Forrest River but over 70 were children under seventeen years of age, and more than half were from outside the Marndoc Reserve.

As the mission struggled, cattle provided another distraction for Gribble. He argued that the country was right, the cattle kings were rich, the government cattle station of Moola Bulla was thriv- ing and, above all, he had ‘excellent qualifications for the work’.21 He put his superlative talents as a nag into action as soon as he arrived in the north west, but poor, harassed Archdeacon Hudleston was sceptical and uncooperative. By 1919, Gribble had decided he could not wait and bought the cattle without permission. The herd was expanded in 1924 after a benefactor left the mission a legacy. Cattle consignments were delivered to the Wyndham meatworks in 1926 and 1928 but the profits Gribble promised never eventuated. Two consecutive ABM Chairmen observed that Gribble was ‘not a businessman’.22

Gribble knew his unauthorised cattle purchases gave the Perth Board of Missions strong grounds for a dismissal. In atonement for his sin he agreed to go on ‘furlough having accomplished all I set out to do and the future is well assured’.23 He filled in the twelve months from April 1920 with a hectic schedule of exhibitions, sermons and conferences in the eastern states, interspersed with a visit to Cairns to attend his daughter Nola’s confirmation.

Archdeacon Hudleston schemed while Gribble was away. Having failed to convince Trower to remove Gribble, he approached the Chairman of the ABM in Sydney. Chairman Needham acknowledged but forgave Gribble’s flaws. After all, Needham argued, it was hard to be a spiritual and business manager at the same time. In the autumn of 1921, Gribble returned to Forrest River knowing his stocks were low and blitzed Perth with complaints that his replacement was an indolent drunkard: ‘another two months [sic] absence on my part and you would have had scandal and disaster’.24 Meanwhile, he tormented the beancounters by refusing supplies from Perth and buying the same goods at inflated prices in Wyndham. The Perth Board of Missions directed the company of Connor, Doherty and Durack in Wyndham to ignore their missionary’s orders. Gribble scarcely noticed. As the dry winter winds of 1921 swept across the north west, Gribble was so consumed with protecting Aborigines from abuse by settlers and police that he had virtually cut all contact with the ABM.