Most of the world celebrated the start of 1929 blissfully ignorant of the circumstances that would soon catapult it into economic depression. For Ernest Gribble, the world was already bleak and hopeless. Amelia now lived in Sydney and almost a quarter of century of managing alone had moulded her into an austere, unyielding matron who was set in her ways. She acquiesced to Gribble’s return—after all, they were married and he had nowhere to go—but she made no overtures to tempt him to stay. He had a loosely formed notion of fashioning a new life as a family man but the chimera quickly vaporised. As each day passed, he felt lonelier and more unwanted. He loathed the city, and he had no work, no savings and fewer prospects. His chief companion was his dog, Nipper—a devoted, loyal barker—and neither spent much time at Amelia’s house in Northbridge. They were more comfortable with the hospitality of Gribble’s sister, Illa, where Nipper was not barred from the house and the ageing missionary was not banished to the porch to smoke his pipe.

Over the years, his passion for writing had come and gone in bursts. Now he turned to it as a refuge and release from the smouldering torment and burning injustice of his recent dismissal. His first autobiography, The Life and Times of an Australian, had been a reflective journey through his childhood and youth. This time he wrote to clear his name as a defender of Aboriginals. Three autobiographies poured forth during the four years after his dismissal and their title pages announced his credentials and implicit purpose:

Pioneer missionary to Yarrabah, North Queensland; Mitchell River, North Queensland; and Forrest River, North Australia; Protector of Aborigines, Queensland, for sixteen years and Protector of Aborigines, Western Australia, sixteen years.

Woven throughout each book was the philosophy that underpinned his life’s work: that ‘the remnant that is left’ could only be saved by segregation on Christian missions. Each book was a statistical litany that showcased his achievements: the number of buildings and converts; Aboriginal involvement in the Church; agricultural progress; and literacy. Peppered in between were descriptions of his experiences bravely confronting danger and hardship to subdue nature and take Christianity and civilisation to the ‘heathen’.

The first publication during these years was Forty Years with the Aborigines. This updated version of Life and Experiences included a chapter on Forrest River and a rebuttal of allegations that he took Aboriginal children from their parents and ignored the authority of Elders. Most children, he maintained, were handed over by their parents and ‘the old men . . . carry little weight’.1 In his next two books, The Problem of the Australian and A Despised Race, he set out to prove explicitly to his critics that he understood Aboriginal language and culture. Nearly half (62 of the 132 pages) of Problem was devoted to descriptions of aspects of traditional Aboriginal society—drawing on other sources to supplement his own knowledge— and he compiled a long vocabulary list for Despised Race that was cut ruthlessly by his editors.

Gribble typed his manuscripts on a secondhand typewriter and flimsy, tissue-thin paper. The traces of a lifetime of frugality shone from each page for he milked the precious paper for every inch of space and let the ink in the typewriter ribbon run down until the print was barely readable. The typescript often drifted off the page as he became immersed in his story, but he had a bushman’s talent for spinning a good yarn. Nevertheless, his editors attacked his manuscripts ruthlessly, with a shrewd eye for dodging controversy. Editors at the ABM collapsed 22 single-spaced, closely typed pages on the 1926 killings and Royal Commission into two banal sentences:

Then, in 1926, complaints were made to the police of the natives killing cattle on the station, and a party of police were sent round to investigate. This led to the awful atrocities, which caused a Royal Commission to be appointed.2

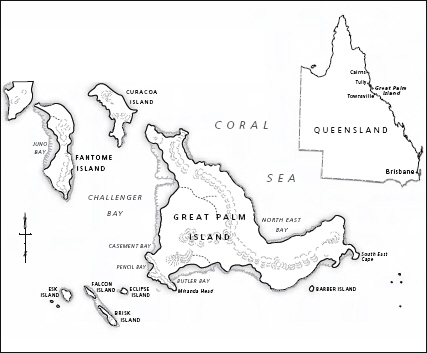

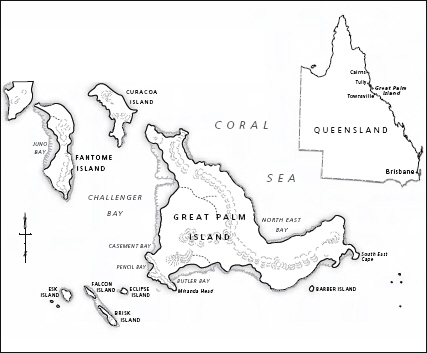

Writing filled Gribble’s time but it did not occupy him. His one wish was to return to missionary life. He pleaded with his friend Chairman Needham to find something. The paternal Needham tried to wrangle him the job in charge of a new mission at Edward River but the Bishop of Carpentaria rejected the proposal without explanation. The ageing missionary had become a problem and Needham was at a loss. It was the lanky and generous John Oliver Feetham, Bishop of North Queensland, who came to the rescue. Feetham’s boundless admiration of Gribble’s fearless defence of Aboriginals outweighed any consideration of his imperfections. There was a difficult post as chaplain on the government Aboriginal settlement at Palm Island going begging, 20 miles off the Queensland coast near Townsville. Feetham decided Gribble was his man.

Gribble scoffed. The job was unworthy of his talents and experience, he told Needham, and the idea of being subordinate to secular officials was preposterous and unpalatable. For a while Gribble blustered about abandoning the priesthood and returning to life as a drover but his threats did not make a more attractive post materialise. Needham’s counsel was blunt: the options were limited for a 62-year-old missionary. Gribble accepted the post.

The Wulgurugaba are the traditional owners and custodians of Greater Palm Island. The Dreaming story about the great Carpet Snake that travelled the coast creating islands from the mounds of his body explains the origin of the cluster of islands that make up the Palm Island group. Captain Cook baptised the islands to conjure seductive images of a steamy, lush Pacific paradise but he only sighted them from afar. Cook never set foot there and his choice of name was wishful thinking rather than reality. The rugged, submerged mountain range is rocky and scrubby with little arable flat ground and no natural supply of fresh running water.

From the mid-nineteenth century, the Wulgurugaba were forcibly conscripted to work the beche de mer and pearling boats. Violence and disease progressively decimated their numbers. By the 1880s only a handful remained. In 1914 the Queensland Government removed the survivors to the Hull River Reserve near Tully but a cyclone flattened the four-year-old settlement killing fifteen inmates. Superintendent Kenny was lanced by a stray shaft of timber while he and his family sought protection from the violent gale and turbulent seas underneath their house. His wife and two children watched helplessly as he died a slow, horrific death. The surviving Wulgurugaba were transported to Greater Palm Island, and their dogs were left to mourn on the beach.

Descendants of the former convict colony continued the British tradition of ostracising its unwanted souls to remote, isolated islands until well into the early twentieth century. From its inception, Palm Island was known as a violent, brutal place. By 1931 more than 1000 indigenous Australians had been transported there. Origin was no impediment to removal and inmates were sent throughout Queensland, the Torres Strait Islands, and as far away as the Northern Territory, New South Wales and Western Australia.

Any offence could lead to banishment: a criminal record, unemployment, old age, destitution, immorality or being an unmarried mother. Some were sent because they committed offences sanctioned by tribal law. Others had disobeyed work orders. Many were children who were transported so they would be saved from the ‘retarding influence of the old myalls’.3 Few knew why they had been removed and fewer had been tried in a court of law. The late Neville Bonner, the first Aboriginal Federal Member of Parliament, grew up on Palm Island and remembered the history of the transportees:

There was no court-case, no trial or anything like that to prove you guilty or otherwise of doing something wrong . . . they could think up reasons . . . if they wanted to get rid of you. You were classified as a trouble maker.4

Confinement was indefinite and depended on the Superintendent’s grace and goodwill. Some inmates called it the ‘punishment place’.

The first Superintendent was Captain Robert Henry ‘Mad Dog’ Curry. A veteran of the Egyptian campaigns during World War I, Curry ran the island like a military depot. Work was mandatory and unpaid, curfews were religiously enforced, public gatherings were prohibited, and recalcitrant inmates were tried and punished in the privacy of his office. Curry kept a cat-o-nine tails on hand to make sure all complied with his rules and, despite an official inquiry and reprimand for breaching regulations by flogging a young girl, complaints about beatings continued throughout his reign.

Curry’s violence and repression, fuelled by copious quantities of alcohol, extended to his treatment of white officials and fostered a climate of resentment and distrust across the settlement. On 3 February 1930, the situation exploded. Curry was drunk and nursing a potent cocktail of pain and drug withdrawal, after a falling out with the island doctor had deprived him of the Novocaine injections he needed to ease his incapacitating headaches. Curry was also anxious about another investigation into charges that he flogged, sexually abused and supplied liquor to Aboriginals. He was certain his enemies were plotting to seize his job. Demented and delusional, Curry embarked on a sixteen-hour frenzy of horror. Clad in a red bathing suit, laughing hysterically and oblivious to the pouring rain, he dynamited his own house—killing his son and stepdaughter—shot and seriously wounded the doctor and his wife and then blew up the administration buildings and set fire to the island. To stop his frenzied destruction, weapons were distributed to the Aboriginal men. Curry was shot by 20-year-old Peter Prior who was later tried and acquitted of murder. In a mysterious historical irony, the report of the investigation into Curry’s administration was handed down on the same day as his rampage. It ‘found a high state of efficiency, both externally and internally in the administration of the settlement’ and that ‘the management reflected the greatest credit on all concerned’.5

Curry’s rampage delayed Gribble’s work on Palm Island. When he arrived in September 1930, the main settlement had already acquired an institutionalised persona. The streets were neatly laid in a grid complete with a school, farm, hospital, administrative buildings and clean, white houses for the officials. The tidy township belied the reality of life for the inmates. They lived in mia-mias of bush timber and coconut palms in camps grouped around tribal and regional connections like Cooktown, Clump Point, Torres Strait, Yarrabah, Gulf, Babinda, and the Sundowners, where the people from the western regions, including the Arunta of the Northern Territory, congregated. The inadequate government rations spawned hunger, malnutrition and illness. In 1924, the annual death rate was 16 per cent per annum compared with the State average of less than 9 per cent. Births did not exceed deaths until after World War II. Some residents discovered that their ability to find ‘bush tucker’ became a saleable skill.

The quasi-military regime continued even after Curry. At night, the children were locked in fenced, segregated dormitories and socialising between the sexes was banned. The day began with bells and concluded at a curfew. Children were beaten or gaoled for swearing. If adults were disrespectful or indulged in illicit sexual relations, their heads were shaved or they were banished to nearby Brisk, Curacoa or Eclipse Island on rations of bread and water. No litany of maltreatment can unmask the human anguish of transportation and institutionalisation. Palm Island split families, separated spouses, orphaned children and left its victims bewildered, confused and grief stricken. Escape attempts were frequent but rarely successful. Few survived the long swim to the mainland through the shark infested seas.

Before 1939, traditional cultural practices, including speaking ‘language’, were offences by decree of the Superintendent and punished with imprisonment or banishment. After 1939, Regulation 21 of the 1939 Aborigines Act banned Indigenous practices without official permission. Rules and regulations did not stop Palm Island’s inmates, however. Tribal taboos reigned in the camps: the people spoke the language of their country; Law and kinship prevailed; medicine men held sway; funeral dances and spirit smokings continued; and inter-group conflicts and pay-back spearings were commonplace. Dr Elliott Murray, the island’s medical officer from 1932 to 1934, documented the healing powers of the tribal doctors, the prevalence of death by ‘pointing the bone’ and the punishment of murderers by ‘the painful rite of ‘‘carving up’’ . . . an outsize steak . . . from his sacro-spinalis muscle’.6 The mainland press revelled in lurid, sensationalised stories that portrayed Palm Island as a hot bed of sorcery, superstition and savagery. These tales affirmed the generalised anxiety that the Aboriginal presence was a threat to the very fabric of white civilisation, and relieved Queenslanders of any moral pangs about banishing their Indigenous peoples to a desolate and remote island outpost.

In many ways, Palm Island was a microcosm of Australia in the first half of the twentieth century. The schools were segregated and Mango Avenue, where the officials lived, was off-limits for inmates. The officials led luxurious, extravagant lives compared to their charges. They had iceboxes, ordered food direct from Townsville, had first choice of all government supplies and free labour to tend their houses and gardens. It was a lifestyle that fomented racial tension. Black and white lived in different realms. Some inmates released their frustration through violence. Others chose the numbing comfort of illegally smuggled alcohol and opium. An undercurrent of nascent resistance permeated all dealings with the white administration that was revealed when tourists visited the island and inmates mockingly presented them with curiosities like:

coral that was not properly boiled and that stank in a few days; boomerangs made falsely to adorn mantle shelves; dogs’ teeth exhumed from middens; nullas daubed with ochre and given a murderous history in pidgin English . . . corroborees where dance steps seen on the cinema were being introduced.7

Residency restrictions prevented Gribble from living on Palm Island so he lived with Bishop Feetham as his personal chaplain and was ferried to and from Townsville. His first impressions of Palm Island confirmed his long-standing prejudice against government settlements, and he was frustrated and disappointed with his new post. He bared his heart and the questions that troubled his soul to his journal. How could he cope with this cesspool of rampant immorality, gambling, alcoholism and violence? How could he work with officials who disdained religion, and married and divorced couples in contempt of the law? How could he submit to an administration that clearly lacked control? The work ‘overwhelmed’ him with ‘anguish’ and for three years he pleaded with the ABM to find him something else:

I know this is God’s will for me yet too I feel and cannot help feeling that I am here on sufferance and also that my Ch[urch] Authies [sic] have shelved me here if not permanently at any rate for a time. My life has been spent in pulling the Church out of Holes. 1st Yarrabah then Forrest River. I do not regret it but I miss my people and the work of building up.8

It was a desire the ABM could not—and would not—satisfy. Forsaken and abandoned, Gribble plummeted into depression:

Once again I am feeling lonely. Years of loneliness . . . divided for many, many years from my family & relatives . . . I long for a wider sphere, long for my beloved Aus[tralian] bush where the whole of my life has been spent. Lord forgive my vain desires.9

Gribble whinged but the reality was that small consolations made life tolerable. Living with Feetham in Townsville, a more relaxed Gribble emerged. The strain around his pursed lips eased and the tension in his wiry limbs dissolved. He read voraciously, developed a fascination for cars, discovered films and, as with everything, was passionate in his devotion to his new interests. He took driving lessons for a while but was notoriously hopeless and the townsfolk of Townsville were relieved when he abandoned trying to get his licence. He also sought out Janie Clarke and visited regularly. His daughter, Nola, had blossomed in motherhood and he collected pictures of her children for his photo album. During quiet moments, he wrote his fifth autobiography, Over the Years. It was serialised by the Northern Churchman and later by the ABM Review after Gribble abandoned a fruitless, twenty-year search for a willing publisher.

His friendship with Feetham grew during these years. Gribble was conscious of the Bishop’s ecclesiastical standing and was always appropriately deferential, sparing the Bishop the vagaries of his swinging moods. The kindly Feetham was devoted to Gribble and saw only an elderly man and a courageous humanitarian who had given his life to Indigenous Australians. With Feetham’s patronage Gribble was elected to the Diocesan Council of North Queensland, a position he held until 1950, and was Secretary of the Synod Mission Committee until 1945. Through these roles Gribble became the diocesan spokesperson on missions and kept a keen eye on nearby Yarrabah. His views and comments were widely reported in the Townsville Bulletin as well as the Northern Churchman. He spoke against miscegenation and assimilation and in support of Federal control of Aboriginals. He had developed some influential allies among humanitarian groups like the Aborigines’ Protection Association and his philosophy shaped missionary work in the North Queensland diocese during the 1930s and 1940s. In June 1941, Bishop Feetham elevated him to Canon of St James Cathedral.

None of this, however, reconciled Gribble to his work on Palm Island, where the parade of different superintendents was a constant reminder that none could match his ability or standards. As far as he was concerned, most were unqualified bureaucrats. He dismissed Superintendent Delauney—a former Prickly Pear Inspector with no qualifications for the job. He treated Superintendent Foote with disdain—terrified of a black uprising and kept a revolver in his desk drawer. The rest he denounced as either too young, too inexperienced, drunkards or lechers who used their position to sexually molest female inmates. It was hard for him to defer to an administration he considered indolent, incompetent and irreligious, but he did not win friends by bluntly pointing out to different superintendents that the job was beyond their abilities. The problem, Gribble explained, was the lack of a Godly man at the head of the settlement.

Nonetheless, amidst the crowd of reluctant inmates on the island, he discovered a small group of familiar faces from Yarrabah who had kept their faith and provided the foundation for a flourishing congregation. With his usual dynamism he quickly built a community of nearly 200 Anglicans complete with a Church committee, choir and two Aboriginal representatives to Synod. Within twelve months, the newly erected St George’s Church, with its thatch roof and plaited coconut palm walls, was too small but it was not until 1935 that the Anglicans secured a lease on the Palm Island Reserve and Gribble’s onerous journeys to Townsville abated. A new church was built with a small, three-room, fibro apartment at the rear that served as a rectory. Now Gribble’s life was centred wholly on Palm Island. He acquired a horse and a launch to keep in touch with his widespread congregation. In spite of dozens of willing helpers, Gribble stubbornly insisted on the superiority of his mechanical skills. More often than not, the engine of the launch lay in pieces on the beach.

With the same colonising fervour that diffused British imperialism throughout the globe, Gribble devised ways to infiltrate every nook and cranny of Palm Island. A network of churchgoers liaised with groups from different areas. The Women’s Guild visited the sick and welcomed newcomers and small chapels were built wherever pockets of people and new settlements sprang up. Gribble’s zeal was more than mere proselytising. It was his blueprint for a new order to supplant the heartless sterility of the white administration and create a compassionate, cheerful home for the island’s inmates. A handful of donated books started a busy lending library and his open air lantern lectures drew large, attentive crowds eager for his stories and pictures of Aboriginal life and missions around Australia. He gave the old thatched church a new lease of life by transforming it into a hall. After years of nagging, he secured a power generator and for years the hall was one of the few buildings with its own power and night lighting. It became a centre for the island’s organised social life—dancing lessons, boy scout meetings, weekly games nights for the men and boys, euchre evenings, band and choir practices, wedding feasts and birthday parties. Gribble introduced weekly ballroom dances. Religion did not matter. The entire community was welcome. He supervised with a careful, benevolent eye, evicting those caught dancing with another man’s wife. Immorality was not tolerated.

Although the Australian Inland Missionaries had been on the island for seven years, Gribble did not believe they had much influence and dreamed of an Anglican monopoly. His hopes were dashed in mid-1931 when Father Moloney of the Sacred Heart Mission arrived to minister to the island’s Roman Catholics. Moloney was serious competition. At first the two priests met for sociable cups of tea and exchanged cards on their shared birth date, but the civility was short-lived. Within eighteen months, Rome’s congregation shot from fifteen to 262 and at least five Anglicans had deserted. Gribble could read the writing on the wall—clearly Rome was out to control the island. The battle lines thus drawn, Gribble declared the two denominations bitter competitors for the hearts and minds of Palm Island’s inmates.

Palm Island’s religious rivalry mimicked the malicious mistrust that sectarianism fomented throughout Australia during the early twentieth century. For the elderly man inducted into the Orange League when he was ten years old, the imperative to save his people from the Popish Anti-Christ became an urgent, all-consuming passion that gave his life meaning and direction. At last, the elusive reason for his banishment to Palm Island was clear. He had a string of stormy disputes with Moloney about plotting to steal his congregation, particularly after the Roman Catholic Bishop baptised and confirmed several Anglicans while Gribble was away. Moloney’s successors did not fare any better. Gribble accused them of buying supporters, seducing Anglican boys with lollies to baptise them covertly, and allowing their women to prostitute themselves for money. As a strict teetotaller, Gribble found Rome’s liberal stance on gambling and liquor especially distressing. This, explained one Anglican defector, accounted for the leakage of his congregation to Rome—Gribble was a wowser.

In a grisly contest for souls, the denominations vied to capture the living and the dying. Sometimes the competition was macabre. When one of Gribble’s congregation died and was buried quickly by the Roman Catholic priest on account of the summer heat, Gribble demanded the body be disinterred and reburied under Anglican rites. Only the intervention of the Superintendent brought the squabble to a close.

It was the arrival of the nuns that most offended Gribble. Their work gave them access to souls at their most vulnerable—the beginning and end of life. On Palm Island the nuns set up a primary school and staffed a Lock Hospital for Venereal Disease and Leprosarium on nearby Fantome Island. Gribble was perplexed by their long shapeless robes, weird head gear and mysterious, feminine ways. He was sure they were trying to seduce his congregation away from him by bribing Anglican girls with wedding dresses to lure them into Roman marriages. He reserved his greatest contempt for the softly spoken Franciscan Missionaries of Mary who arrived from Quebec in 1944: ‘dago disturbers’ out to ‘capture the whole outfit’.10 Gribble wanted to build a house on Fantome Island to combat the influence of the nuns over the sick, but the Roman Catholic priest threatened to withdraw his staff if the authorities approved the request, complaining that Gribble’s attitude was ‘belligerent and unfriendly’ and his only intention was ‘to stir up strife’.11 Gribble continued ferrying backwards and forwards to minister to sick and dying Anglicans in the care of the Roman Catholics.

Among the familiar faces on Palm Island was John Mitchell Barlow, son of Menmuny of Yarrabah. In 1933, Barlow distributed a petition to the press and Synod denouncing the Roman Catholic clergy on Palm Island for proselytising and criticising the Anglican sacraments. Unfortunately, none of the petitioners were signatories and Superintendent Delauney, a Roman Catholic, claimed Barlow confessed to acting on Gribble’s instructions. The incident attracted wide publicity and incited sectarian passions throughout north Queensland by degenerating into a vicious, three-way exchange in the press of allegations between Feetham, Gribble and the Roman Catholic Bishop.

Determined not to be outdone on any front, Anglican rites on Palm Island soon matched the ostentation of Roman Catholicism. Gribble introduced the Angelus—an especially Anglo-Catholic prayer—as well as processions through the settlement on Sundays and feast days. When the Roman Catholic priest acquired a wireless, Gribble procured a radio to reclaim Anglicans lured away by Rome. When Roman Catholic girls were sent to work for Catholic families on the mainland, Gribble quickly pushed aside his longstanding opposition to white employment of Aboriginals and insisted his Church send their girls to work for Anglican families. Nevertheless, the vibrant social and spiritual life of his Church offered inmates an escape from the brutality of life in this world as well as in the next, and the Anglican Church was soon the dominant religion on Palm Island with almost 1000 baptisms between 1930 and 1950. Gribble’s interaction with the people revealed the compassionate soul behind his stern façade: daily visits to rub liniment on an injured back; mediation in innumerable domestic disputes; and solace offered to the sick, dying and those in gaol. These same human qualities were exposed when Gribble collapsed with laughter during Evensong when ‘some animal in the thatch roof dropped its excrement fairly on the top of [his] bald head’ or wiggled his ears during sermons to entertain the children in the congregation.12 His compassion did not temper his authoritarian streak: he took his congregation to task during sermons and lectured the children for hours on end. The young boys who got into his communion wine or stole his fruit got a well placed whack around the ears. He trained his dog to bail up parishioners in the street, hunt them into church and stand guard at the church door so no one could escape before the last hymn. In fact, Gribble approved of many of the administration’s more draconian policies: gaoling adulterers—current in the 1930s; separating children from their parents into dormitories; and banishing wrongdoers to outlying islands. He had a brainwave in the middle of World War II when American GIs invaded Townsville: a boot camp should be established for Palm Island’s recalcitrant inmates so they would ‘be under strict control, live in barracks, drilled and employed and when proved worthy then drafted to live amongst decent people’.13

His contemptuous defiance of the island’s administration set Gribble apart from the white officials and won him respect. His reputation as a great humanitarian preceded his arrival and his constant stories of his past fortified his standing. His enthusiastic defence of any inmate in battle with the administration confirmed his local credentials as a champion of Aboriginals. Gribble defied the administration by growing fruit and vegetables and selling them cheaply to supplement the residents’ inadequate, government rations. A decree that only white staff could use the island’s tennis court goaded Gribble into building a tennis court for the Aboriginal inmates. He fearlessly challenged superintendents about the inmates’ living conditions and the practice of gaoling residents without trial or by trial in camera. When superintendents ignored his demands, he promised to complain to the Home Secretary or the press. His threats reduced most to quivering submission. Since the victory of the Royal Commission, Gribble’s network of influential friends had grown and the defiant priest shamelessly exploited his contacts in humanitarian circles to get what he wanted and to fight for his vision of justice for Aboriginals. He corresponded regularly with Chairman Needham and Reverend Morely, Secretary of the Association for the Protection of Native Races (APNR). Both were loyal supporters. The devoted Bishop Feetham relayed all Gribble’s complaints directly to the Home Office and made sure Gribble met with senior government officials when they visited Townsville. Years of experience and a reputation as a troublemaker guaranteed that Gribble’s views were noted if not heeded. Even strangers commented on the fire in his belly:

He was tall, spare, about sixty-five, with a purpose that kept his spirit and constitution iron-hard and rustless. His eyes glowed sombrely. He had spent a lifetime among the blacks . . . and he knew them. They were his friends . . . When the government rested too-heavy a hand on them, he, a respected clergyman, was not afraid to be agin the government. It had not made him a popular figure. He had fought many fights and written fiercely for a newer freer more liberal Black Australia Policy. He burned with injustice.14

It was during his years at Palm Island that he developed a friendship with the new generation of Aboriginal leaders, William Cooper, Secretary of the Australian Aborigines’ League (AAL), and William Ferguson, founder of the Aborigines’ Progressive Association (APA). The three men discovered they had personal as well as political links. Cooper grew up on Maloga Mission, run by JB Gribble’s long-time friend and mentor, Daniel Matthews, while William Ferguson was born at Darlington Point and during the 1890s went to school at Ernest Gribble’s beloved Warangesda mission. They were thrown together by the campaign for Federal control of Aboriginals. Years of working under ineffective State authorities convinced Gribble that Australia’s Indigenous communities were a national responsibility. He pushed for Federal control during the 1927 Royal Commission into the Constitution and later in his addresses to the North Queensland Synod and his correspondence with government officials. He urged organisations like the APNR to put their weight behind the cause. A petition to King George was underway and Gribble offered to collect signatures from the inmates of Palm Island. The Commonwealth and three States refused to support the petition and the Chief Protector of Queensland banned Aboriginals from signing. Gribble relished this sort of struggle and ignored Chief Protector Bleakley’s directive. The petition was sent to Prime Minister Lyons but he failed to forward it to King George and a flurry of letters flew backwards and forwards between Gribble and his humanitarian allies. Gribble urged William Cooper to appeal to Reverend Baillie of St Georges Chapel, Windsor, because he had access to the Royal household and could press their case. The petition died but Gribble’s commitment shone. The Australian Aborigines’ League acknowledged his services by granting him the rarely awarded honour of life membership of the AAL.

A captive to his proven formula, soon after his appointment, Gribble summoned James and Angelina Noble to help him win over the people of Palm Island. The Nobles arrived in 1933 but illness forced James to retire to Yarrabah two years later. It was a welcome relief to all. The intimacy between Gribble and Noble had never rekindled since their clash over Stuart Wajimol’s murder, and the residency restrictions of the Act forced the Nobles to eke out a miserable life on nearby Esk Island. Gribble, forever energetic and brimming with new ideas and projects, whinged that the ailing James was a burden. He regretted his callous lack of sympathy when the family had gone. News from Yarrabah of Noble’s ailing health jolted Gribble into realising the need for a new generation of Aboriginal Church leaders to follow in Noble’s footsteps. He drafted a motion to Synod. It was an ambitious scheme. In the 1940s, there was no school for Palm Island children beyond grade 4 but Gribble planned a program to sponsor the secondary education of promising Anglican children on the mainland. It would be called the James Noble Education Fund. He envisaged it would train Palm Islanders:

for future usefulness amongst their own people . . . on Aboriginal missions and Settlements [to] fill many subordinate positions [under the supervision of] white officials.15

The genesis of his idea was the work of Reverend Morrison who established a ‘college’ at Yarrabah in 1909 to train Aboriginal missionaries. Later, Gribble organised the secondary education of James Noble’s son, Mark, and the Church Army sponsored the nursing training of Muriel Stanley from Yarrabah. With the support of Bishop Feetham and agreement from the Home Office to pay half the costs, the James Noble Fund came into being in 1942—one year after James Noble quietly passed away. Gribble managed the program, personally selecting each promising young student and writing glowing reports of their successes for Church journals. Competition for sponsorship was sometimes intense but it is impossible to decipher who or how many were educated through the Fund for, as Gribble aged, his records became more muddled and confused.

It filled Gribble’s heart with pride that one of the Fund’s beneficiaries became a typist and pay-clerk in Ingham, but it did not match his notion of the Fund’s purpose or his vision of Australia’s Indigenous people living on segregated settlements under benevolent, missionary guidance. It was difficult for Gribble to relinquish the values that had shaped a lifetime’s work and to come to terms with this unfamiliar new world: ‘these people are not as the Abos [sic] were in these parts 40 years ago. Many read and write & are thinkers and know what is right and just’.16 His old fashioned notions did not worry Palm Islanders. His history and good intentions pardoned and protected him from criticism. Neville Bonner remembered that:

The Aboriginal people had such a love and respect for Father Gribble, no one would dare say anything about him that was in anyway derogatory . . . it didn’t matter what Church you belonged to.17

Age took its toll and from the 1940s, questions were being asked in the offices of the ABM in Sydney. Surely it was time for the old fellow to step gracefully aside? Until his death in September 1947, Bishop Feetham protected Gribble and would not hear of his retirement. Feetham argued that Gribble’s past entitled him to ‘die in harness’ and ‘it would be wasteful and unjust to put him on the shelf’.18 It was clear, however, that he needed an assistant. The Church sent a succession of promising hopefuls but none could match Gribble’s exacting standards. His reputation for being notoriously difficult and unrealistically demanding made it increasingly impossible to entice anyone to help. Poor Feetham was very fond of old Gribble but how could he manage an elderly priest who accused his assistants of lacking a priestly vocation because they rested on their day off? The same problem blighted Gribble’s domestic domain until the Church Army sent the Killarney-born, Sister Irene Johnson, in 1939. Gribble and Johnson were a perfect match: determined, cantankerous and passionately devoted to their work. Neville Bonner remembered that they:

. . . fought . . . like two . . . bloody Kilkenny cats . . . He was the boss and this young woman gonna come . . . throwing her weight around. Oh the women used to tell me some stories . . . they reckoned they used to often hear them arguing the toss . . . No-one ever told Sister Johnson what she had to do.19

Sister Johnson stayed for ten years and made sure Gribble changed his clothes and had his meals at roughly the right times. He needed looking after. By 1949, he was 80 years old and withered by time and work. He was almost deaf but refused to get a hearing aid. Respiratory problems blighted his life, and even the walk up the gentle incline of Gribble Street to his church left him breathless and weak. He was often smitten by painful bouts of thrombosis that confined him to his bed for weeks, and he never left the rectory without a walking stick. Reluctantly, he delegated the job of reciting the graveside burial rites because the long walk from the church to the cemetery was too much. He would not concede that age was slowly and unrelentingly creeping up but his correspondence was increasingly disjointed and repetitive. It distressed him when he was forgetful and lost the thread of a conversation, but his memories of Yarrabah and Forrest River glowed vividly and he talked nostalgically of his wife and idyllic times past. As he aged, his muscular body became thin, frail and brittle, and he seemed smaller—as if time had worn away the inches. He neglected himself and forgot to eat and the skin hung loosely on his shrinking limbs. Sunday services left him exhausted and he spent most of Monday sleeping. After Sister Johnson left, the kind, loyal women of St George’s Church kept Gribble alive by silently taking charge of his duties and his cooking, cleaning and washing. May Smith remembered Father Gribble:

taking the service . . . when he reading the Bible, you can see that he miss something . . . He missing something . . . not saying the right thing. I said . . . ‘Father forgetting himself’. When he preached he don’t preach it properly, you know? He forgetting what he’s saying . . . They said ‘Father too old to take service’ . . . he . . . almost fall when he giving communion. He have to have a man beside him, a helper, you know, to walk with him to each person . . . he have to hold Father because he can’t come down that step . . . That man had to help him down. Father was too old. We said that. The people, you know, we talk. He was too old to come down the step to give Communion. He was shaking.20

In 1950, death hovered and the Superintendent of Palm Island, George Sturges, wrote to the Gribble family urging them to visit and pay their final respects. Old Gribble surprised everyone by recovering but he found it hard to move around and spent most of his remaining years confined to the small rectory at the back of St George’s Church. Being unable to fulfil his clerical duties distressed him deeply and he worried that he was losing people from his Church. He pleaded constantly for an understudy to take up the reins but the Church found it impossible to persuade a priest to work with him.

As awareness of death’s inevitability jolted his consciousness of his own mortality, he craved a spiritual and moral heir. Time had blurred his resentment of being pushed into missionary work under similar circumstances by his own father. Now his only thought was to ensure that the family’s missionary dynasty continued. He suggested his eldest son, Jack, as a possible successor but Chairman Needham declared him ineligible. Jack had been forced to resign from Forrest River Mission after allegations that he flogged inmates, chained them to posts for sexual offences and poured water over sleeping boys. Besides, Needham pointed out, Jack was not a priest and a serious head injury during World War II had left him with distressing, frequent headaches. Gribble proposed his second son. Eric had studied for the priesthood and was ordained in 1924. Gribble was positive he would be loyal to his plans and methods. Eric agreed to fulfil his father’s wish but Bishop Feetham would not have it. He considered Eric:

a terrible young man. I had him at Hughenden and he was drunken. He went to Longreach and was more drunken. His other peculiarity was pugilism. He knocks people down in the street and has to pay damages. [Feetham had] stopped him everywhere by warning Bishops against him.21

Age brought into focus life’s omissions. Fantasising about the family solidarity and companionship that had eluded him, Gribble redrew his relationship with Amelia and his sons in his imagination. He dedicated his autobiography Over the Years to the ‘wife who has faithfully borne her part in Missionary work’ and in his final weeks talked with sadness and sentimental attachment about the woman with whom he could not share a life. The distant past was more vivid than the present. He crafted his final autobiography during the 1940s and tellingly entitled it The Setting Sun, but ripping yarns of missionary adventures belonged to a different, long-gone world. The Setting Sun met the same fate as his previous autobiography and, unable to find a publisher, a disappointed Gribble accepted serialisation in the Northern Churchman (1940s) and the ABM Review (1950s).

Gribble’s long career had made him a legend in humanitarian circles. In 1953, he received the Queen’s Coronation Medal in recognition of his work for Aboriginals. He was thrilled. Time had not faded his devotion to the monarchy and when one of his congregation invited him to a birthday party or a special occasion, he proudly donned his treasured award—at last, public acknowledgment of his efforts. In January 1957, his work was acknowledged again with the presentation of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his contribution to the ‘uplift’ of the Aboriginals. The elderly missionary was delighted. Ian Shevill, Bishop of North Queensland, decided the OBE decoration ceremony in Townsville was a chance to save Gribble from himself and to force him into retirement. But Gribble, cagey as ever, knew he would not be allowed to return to Palm Island. He refused to attend the ceremony and continued to talk about his future plans for the island. As a last resort, Shevill announced that Gribble’s salary would be terminated at the end of 1957 and sent the air force crash launch—generally used for emergencies—to collect him. A crowd of friends gathered on the beach and cried as they watched the stubborn, protesting priest carried through the shallow water to the launch. Some believed his departure killed him: ‘He died of a broken heart. He did not want to go. He wanted to die with his people’.22

Gribble was sent to Yarrabah. His body and mind faded quickly but word of his return spread quickly and, during the weeks that followed, a flood of Aboriginal visitors—old friends and younger generations reared on stories of a life of stability and order with Dadda Gribble—made their way to Yarrabah to pay their last respects and attend his funeral.

As Ernest Gribble’s life neared its close, the controversial missionary occupied a more ambivalent place in the collective memory of non-Aboriginal Australia. A small constituency recognised him as a humanitarian and defender of Aboriginal rights but in 1949 his Golden Jubilee in Holy Orders and 80th birthday had passed without notice or comment. In 1951, the ABM Review wrongly attributed his autobiography Over the Years to JB Gribble, crediting JB with establishing Forrest River Mission and playing ‘an important part’ in the 1927 Royal Commission. Ernest Richard Bulmer Gribble died in October 1957. After 65 years of dedicated missionary service the wrong name was engraved on his tombstone. It read ‘Ernest Reginald Bulmer Gribble’.

A generation later in mid-1992, crowds of well wishers swarmed to Trinity Bay to commemorate the centenary of the foundation of Yarrabah. After decades of wrestling to balance God and mammon, the Anglican Church had handed secular control of Yarrabah to the Queensland Government during the 1960s. The Church’s presence was still pervasive but the High Church flavour of the Anglican rites was overlaid by a fundamentalist zeal that resonated with the mysticism of the Dreaming and the evangelical roots laid down by Ernest Gribble.

Leading the official celebrations was Bishop Arthur Malcolm, Australia’s first Aboriginal Anglican Bishop, former minister on Palm Island and heir to the path forged by James Noble. A crowd of Gribble descendants—black and white—were among the specially invited guests who came to celebrate and pay their respects. The atmosphere was buoyant and festive. It was a time for remembering the history of a community, honouring its people and paying tribute to the man who had defied the odds, stepped into his father’s shoes, forged a vibrant, lasting Christian enclave in north Queensland and devoted the rest of his life to Indigenous Australians.

Two years later, an article appeared in The West Australian to ensure that the controversy that haunted Gribble’s life continued to taunt his ghost. Reviewing some of the evidence presented to the Wood Royal Commission and drawing on fragments of memoirs written by Constable St Jack, historian Rod Moran alleged that the Marndoc killings never happened but were the fabrication of a deranged, vindictive priest to conceal his illicit affair with an Aboriginal woman. Politics and history merged in the ensuing debate, with conservatives and the right wing literary magazine, Quadrant, arguing the revisionist case for re-writing the history of white Australia’s maltreatment of its Indigenous peoples.

Ironically, the squalling dust of academic duels echoed the tragic dualities that marked Gribble’s world: conscious and unconscious motive; protection and oppression; escape and refuge; resilience and defeat; altruism and self-interest; and reality and illusion. These oppositions were embedded in the life and work of the insecure authoritarian who fought with all his heart to protect Aboriginal Australians and fulfil his paternalistic vision, but with only a partial understanding of the complex forces driving his actions and the actions of others. Today, as in the past, Ernest Gribble’s life stands as a testimony to the intricate intersection of personality, experience and culture that shaped Australian race relations and touched all who struggled to create a new space in the blurred boundaries between culture and race.