MAY 14, 1942. PEARL HARBOR, OAHU, HAWAII, FIVE MONTHS AND ONE WEEK AFTER THE JAPANESE ATTACK.

A soldier stood with a loaded gun in front of a locked steel door. He was guarding the secrets buried below from spies and thieves. No one was allowed to talk about what went on in the “dungeon,” and if anyone did, their life was at stake. The armed guard stopped anyone who tried to enter. If necessary, he would shoot to kill.

A tall, thin man with dark hair and glasses was facing the locked steel door. The armed guard didn’t bother him. That’s because Lieutenant Commander Edwin Layton, known as Eddie to his friends, possessed the security clearance to enter. Plus, he was a regular. The soldier unlocked the door for him and stepped aside.

Lieutenant Commander Edwin Layton

Eddie rushed down the flight of stairs deep into the dungeon. He stopped when he got to the bottom and stood in front of another locked steel door. As he waited anxiously for it to open, he thought about the urgent phone call he’d received earlier in the day.

“I’ve got something so hot here it’s burning the top of my desk!” said Lieutenant Commander Joseph J. Rochefort.

“What is it?” asked Eddie.

But Joe wouldn’t tell Eddie over the phone. Since Joe wasn’t one to exaggerate, Eddie immediately stopped what he was doing and rushed over to meet with him.

Lieutenant Commander Joseph J. Rochefort

Eddie and Joe, who were both known for their quick wit and brilliance, became lifelong friends when they met onboard a ship making its way across the Pacific to Japan in 1929. The navy had sent them to Tokyo to learn Japanese. At the time, it was rare for any American to speak Japanese, but it wasn’t unusual for the Japanese to be fluent in English.

During their three years in Japan, Joe never once mentioned to Eddie that his background involved cryptography, a relatively new field involving cracking codes from intercepted messages. The navy called a cryptanalyst a “cryppy.”

Following his three years in Japan, Eddie would find himself back in the United States working in naval intelligence. Using his firsthand knowledge of Japan and by studying detailed maps, Eddie identified strategic targets within Japan’s electric power distribution network for the United States to bomb in case of war.

During this time, Eddie was also assigned to naval communications and introduced to code cracking, becoming a cryppy himself. He and Joe would cross paths again in 1936 when they were assigned to the same ship. And, five years later, on May 15, 1941, their paths crossed once more when Joe was assigned to work in the dungeon.

Joe was the head cryppy in the dungeon, located in the basement of the administration building of the Fourteenth Naval District. Being the head cryppy meant that Joe was the commander in charge of the combat intelligence unit, also called Station Hypo.

Station Hypo didn’t really describe the group — and this was intentional. The name was a cover to keep their work in the dungeon a secret from everyone. If the enemy ever found out who worked there and captured them, they would be tortured or even killed in an attempt to get top secret information.

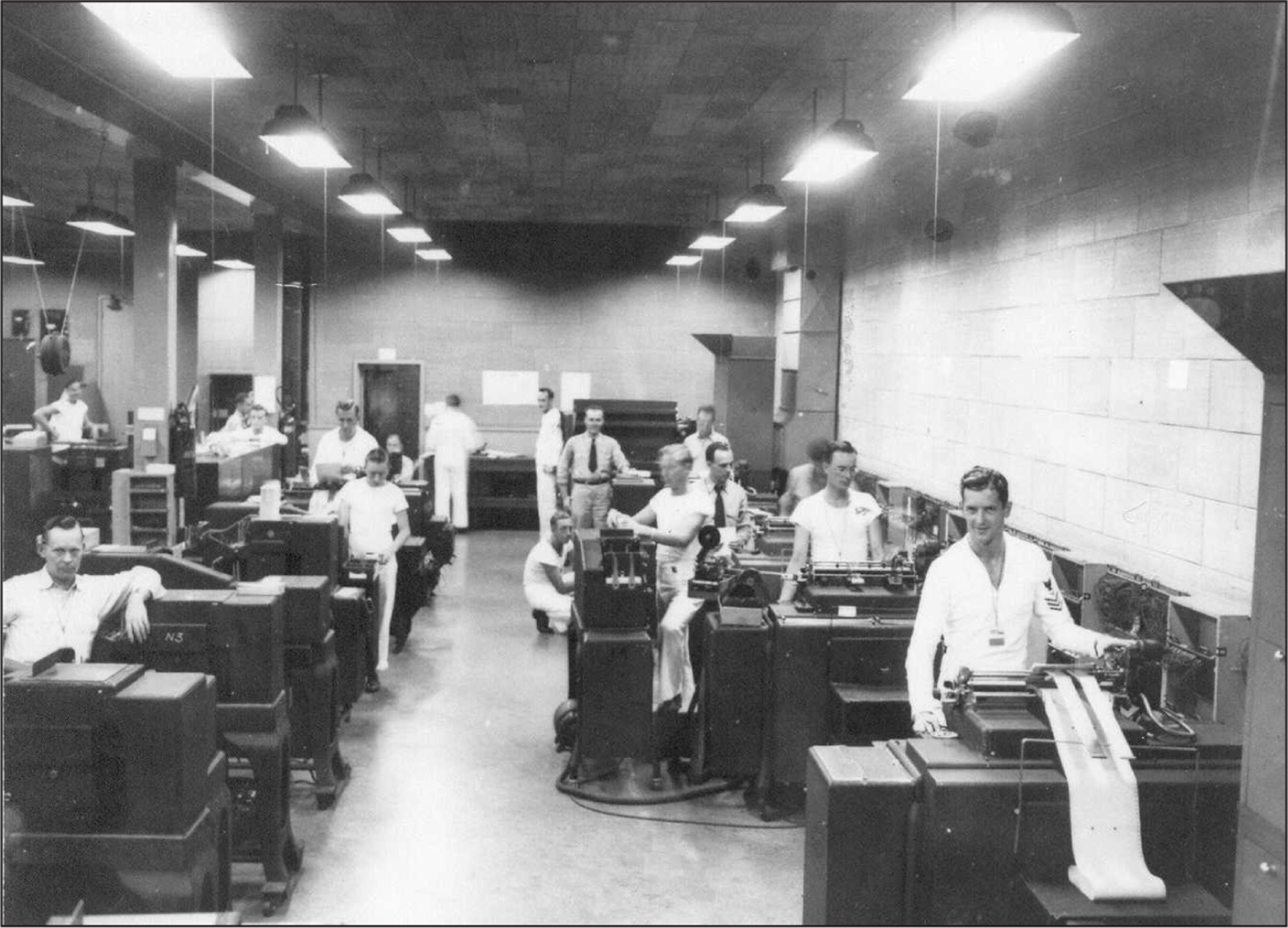

Machine operators inside Station Hypo

Joe oversaw a team of one hundred cryppies, translators, typists, punch card operators, and clerks. Their top secret work involved cracking the Japanese naval traffic codes, specifically the Japanese Navy 25, or JN-25, by intercepting Japanese messages. This was no easy feat.

The navy set up listening posts in China, Guam, the Philippines, Hawaii, and Washington state. At these posts, radiomen, called roofers, wore headsets and scanned the radio airways. They were listening to intercept the Japanese Morse code messages. The roofers would translate the Japanese Morse code of dots and dashes into Japanese kana characters, which represent the phonetic sounds of the Japanese language. Any secretly coded messages were then sent over a secure cable line or delivered in person by a courier to the cryppies, who tried to convert the kana characters into English. Anything they discovered about the Japanese navy’s next plan of attack, Joe reported to Eddie who, in turn, informed Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

Admiral Nimitz was the commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. He needed to know the exact location of the next Japanese attack. The situation was dire.

Since the 1930s, the Japanese had been aggressively expanding their empire, which they called the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japan’s main motivation was its need for resources, such as oil, rubber, tin, and nickel, for military armaments. To get these, they conquered countries rich in these resources. The Japanese leaders claimed that the resulting economic growth would bring them out of the Great Depression, an economic crash that was plaguing the world.

Although Hirohito, the emperor of Japan, was worshipped as a god, he didn’t actually run the country. General Hideki Tojo, who became Japan’s prime minister on October 16, 1941, and other military leaders made the decisions and controlled the government.

In fact, Emperor Hirohito opposed the military leaders’ decisions but didn’t dare voice his opinions. He feared they would turn against him — General Tojo was known to assassinate anyone who stood in his way.

The Japanese military was undefeated and unstoppable. The soldiers were well trained, highly skilled, disciplined, and followed the samurai warrior code of bushido, meaning they valued honor before their lives and would fight to the death. To a Japanese soldier, it was extremely shameful to surrender, and those who did were tortured and executed.

Japan wanted to be a world power and rule all of East Asia and the Pacific. In 1940, Japan formed an alliance with Germany’s Adolf Hitler and Italy’s Benito Mussolini, who were leading wars to expand their own empires in Europe and North Africa. The alliance was called the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis. Hitler promised the Japanese everlasting domination in the Pacific region — including the west coast of North, South, and Central America — if they went to war.

On December 7, 1941, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of Japan’s Imperial Fleet, masterminded the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. During the two-hour bombing, 2,343 American soldiers were killed and 1,272 were wounded. The Japanese sank four American battleships, and of the 394 aircraft, 188 were destroyed and 150 were severely damaged. Japan successfully brought the U.S. Pacific Fleet to its knees and brought America into World War II.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

With the United States weakened and unable to stop the Japanese in the Pacific, it only took the Japanese six months to quickly and easily conquer Guam, Indochina (now parts of Laos and Vietnam), Thailand, Wake Island, Hong Kong, Manila, Singapore, Malaya, Java, and Burma (now Myanmar).

Admiral Yamamoto needed to act fast before the United States had time to recover and gain strength. His strategic plan was to spur the Pacific Fleet into battle and annihilate it.

With only three battleships left, Admiral Nimitz’s resources were low, and the stakes were incredibly high. If he made one wrong decision, the United States could lose the war with Japan.

Joe Rochefort and his team were frantically trying to find out where the next strike would be so that Admiral Nimitz could ambush the enemy and turn the odds to favor the United States.

Back in the dungeon on that day in May, the steel door opened, and Eddie walked into the cold, windowless room. The air conditioner was blasting to prevent a meltdown. The dungeon was a cutting-edge, high-tech operation of key punchers, collators, and machine tabulators.

The team received five hundred to a thousand intercepted messages each day. For each hundred-word message, two hundred punch cards were made. A punch card is made with a machine that looks like a typewriter. Each key on the typewriter-like machine corresponds to a letter or number. When the key is hit, a hole is punched into a card that represents that particular letter or number. By the end of April, the team had used two to three million punch cards. The desks and floor were overflowing with stacks of papers because there was no time to organize and file them, but Joe was a walking encyclopedia of information.

“I could remember back maybe three or four months,” said Joe. “Everything was in my head. Eventually, of course, you’ve got to get away from this. You’ve got to get organized. But we didn’t have time to get organized.”

Like most cryppies, Joe was a natural at solving crossword puzzles. He also loved playing bridge, a trick-taking card game that requires tactics, probability, communication, and memory.

“If you desire to be a really great cryptanalyst, being a little bit nuts helps,” said Joe. “A cryptanalyst from those that I have observed is usually an odd character.”

But, of course, Joe didn’t consider it odd that he wore a reddish smoking jacket over his navy uniform and slippers on his feet. To Joe, it was perfectly logical. The smoking jacket kept him warm, and his slippers were comfortable.

It was typical for Joe to work a twenty-two-hour shift before taking a break, but he wouldn’t go home to sleep. Joe only went home “when someone told me I ought to take a bath.” Instead, he would stretch out and nap on one of the cots set up in a corner of the dungeon.

“An intelligence officer has one task, one job, one mission,” said Joe. “This is to tell his commander, his superior, today, what the Japanese are going to do tomorrow. This is his job. If he doesn’t do this, then he’s failed.”

When the Japanese shocked the Americans by sailing across the Pacific undetected with their battle fleet and bombing Pearl Harbor, Joe felt he’d failed in his mission.

“I felt very guilty that I didn’t know what was up on December 6. I should have, but I just hadn’t enough time or personnel,” said Joe.

Cracking codes wasn’t an easy job and Joe had a stomach ulcer to prove it.

“It wasn’t that we could read their [the Japanese] transmissions like we could a newspaper,” said Joe. “We’d find clues to a new message buried in some old message. That’s why the place always looked in such a mess. We were always pawing through old messages.”

The JN-25 code had forty-five thousand groups of five digits, each of which represented a Japanese word. A Japanese word or idea is represented by a picture that contains one to thirty strokes.

A major difficulty for the American codebreakers was homonyms. A homonym is a word that has more than one meaning. In English, bear is a homonym. Bear can mean to carry or it can refer to the shaggy-haired wild animal. In Japanese, the word seiko means watch, success, starlight, perfume, and it has more than a dozen other meanings. There are thousands of homonyms in the Japanese language.

To further boggle the minds of code crackers, random numbers were thrown into the mix to increase the level of difficulty of deciphering the message.

Tommy Dyer, one of the cryppies, at work cracking codes

After spending hours trying to decipher an intercepted message, some parts were still too difficult to crack, and blanks would remain. An example of a partially deciphered message that Joe’s cryppies worked on looked like this:

STRIKING FORCE OPERATIONS ORDER 6.

Commander Destroyers STRIKING FORCE, will assign 4 destroyers (for each group?) to screen the below units en route _______:

A. AKAGI

B. HIRYU, HIRI, KONGO

Change screening (orders) for SORYU and KIRISHIMA.

Each ship of below units report date when they will in all respects be ready for sea.

When the cryppy couldn’t crack any more of the code, he would hand it off to Joe, who would try to figure out any blanks that were left in the message. He would review and fill in the blanks of an estimated 140 messages a day.

On May 14, 1942, when Joe read the Japanese words koryaku butai, meaning “invasion force,” in a partially decrypted message, followed by the letters AF, he made a quick deduction. He called Eddie and told him to hurry to the dungeon. Joe knew AF was an island air base, and he had a hunch it was Midway — a U. S. territory northwest of Honolulu in the Pacific Ocean.

Eddie left the dungeon to immediately inform Admiral Nimitz. “From that afternoon on,” said Eddie, “despite all that has been written, there was never any doubt in Nimitz’s mind that Midway was the main objective of the Japanese operation.”

But other people weren’t convinced.

“Oh, it was quite a scene,” said Joe. “The Australians were telling us the Japanese were going to come after them. The army was telling us the Japanese were going after San Francisco. I told them the target would be Midway.”

Over the next five days, Joe hatched a plan to prove his hunch was right. Joe’s assistant, Lieutenant Commander Jasper Holmes, told him the island of Midway depended on a facility to supply fresh drinking water. On May 19, 1942, Joe asked Admiral Nimitz to order an uncoded message be sent in plain English stating that the facility was broken and Midway needed a supply of fresh water delivered quickly.

As suspected, the Japanese intercepted the message, and on that same day, the Japanese intelligence unit on Wake Island sent a message to Tokyo informing them that AF was short of fresh water. The Americans intercepted the message and it confirmed, without a doubt, that AF was Midway. But the cryppies’ work wasn’t finished. They still didn’t know the specifics, such as when it was going to happen.

As luck would have it, on May 20, 1942, Admiral Yamamoto sent a ciphered message that laid out the details of the entire Japanese operation. The U.S. naval intelligence intercepted it, and Joe and his team worked around the clock cracking it.

Five days later, on May 25, 1942, 90 percent of the message was deciphered, and Joe delivered the information directly to Admiral Nimitz. Joe knew the details of Japan’s next plan of attack — and the Japanese weren’t just going to bomb and obliterate the U.S. forces on Midway.

They would first attack the Aleutian Islands, the thousand-mile chain of volcanic islands that extend from the tip of the Alaskan Peninsula to the Russian Komandorski Islands.

The Japanese planned to bomb the largest community in the Aleutians, Dutch Harbor, where Fort Mears army base and the Dutch Harbor naval operating base were also located. These two military installations were the only defenses in the Aleutian Islands.

The Japanese strategized that the bombing raid on Dutch Harbor would divert Admiral Nimitz’s attention and draw his fleet away to the north, leaving Midway wide open for bombings and an invasion. After the raid, they planned to invade and occupy two islands at the western end of the Aleutian chain, Attu and Kiska, giving them a toehold in Alaska.

Admiral Nimitz was forced to make a dire decision: How would he defend Midway and the Aleutians against Japan’s immense fleet with a battered and weakened Pacific Fleet?

Basing his decision solely on the cryppies’ intelligence, Admiral Nimitz took a huge risk. He sent his entire carrier fleet to Midway to battle it out with the Japanese, but he also sent Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald to command a small fleet in the Aleutians.

Admiral Theobald’s mission was to defend the Aleutians from the Japanese invasion. But he didn’t. Instead, he made a fatal mistake that would end his career.

Theobald chalked up the decrypted messages as guesswork, and he assumed Admiral Yamamoto was trying to trick him by sending a fake message outlining a phony strategic plan. Theobald strategized that the Japanese were trying to lure his naval forces to the western Aleutians, where they would be trapped and destroyed. So he ignored the intelligence when he outlined his plan of operation.

He based his plan on the theory that the real Japanese plan was to first attack the Alaskan army airfield bases Fort Glenn on Umnak Island and Fort Randall at Cold Bay, which had been built to provide air protection for the Dutch Harbor naval base. When the two bases had been seized, the Japanese would attack Dutch Harbor. After the Japanese gained control of Dutch Harbor, they would be in a position to launch an attack on the Kodiak Island–Kenai Peninsula area, which would position them to launch air attacks on the mainland of Alaska as well as Seattle, San Francisco, and Vancouver, British Columbia, in Canada. As a result, Theobald planned on ambushing the Japanese four hundred miles south of Kodiak Island, which is a thousand miles east of the Aleutians.

So while Midway would mark a turning point in the war for the United States and be celebrated as a victory, the same wasn’t true for the Aleutians.

They were about to be dealt a deadly and devastating blow.