JUNE 6, 1942. ATTU, ALASKA, THREE DAYS AFTER THE JAPANESE FIRST BOMBED DUTCH HARBOR.

It was an unusually sunny and windless day when a quiet stillness descended on the village of Attu in the Aleutian Islands. It lingered with an unshakable persistence like the thin ring of fog that clung to the foot of the rugged mountains. But this stillness wasn’t calming. It was menacing.

Village of Attu

As Mike Lokanin walked over the wooden sidewalks that covered the slippery mud, a nagging dread kept clouding his thoughts, and sometimes his heart thumped so hard he felt like he was choking.

When he looked around the island, which was located on the westernmost tip of the Aleutian chain, everything appeared beautiful to him. The mountains were a lush green. Wildflowers were sprouting and beginning to bloom. As he gazed at Chichagof Harbor, the island looked like it was sitting on top of the ocean.

Mike was seven years old the first time he laid eyes on Attu. That was twenty-three years ago, in 1919. It was the same year the deadly Spanish flu swept through Alaska and killed his parents.

Mike Lokanin (front in sailor’s hat) with Attu natives

It was also the year Mike first met Alfred Somerville, captain and owner of the trading schooner Emma. They met when Captain Somerville brought some medicine for Mike’s dad. This first meeting led to events that would change Mike’s life, forever sealing his fate.

After his parents’ deaths, orphaned and with no one to take care of him, Mike came onboard Captain Somerville’s trading schooner even though he wasn’t sure where they were headed. Captain Somerville took Mike under his wing.

They sailed one thousand miles away from Unalaska, Mike’s hometown. Then one morning when Mike woke up, everything was quiet. He got out of bed and went to the deck to take a look.

The first thing Mike saw when he looked out on the calm Chichagof Harbor in Attu was a skin boat with two men paddling toward the schooner.

Before the canoelike dory became the boat of choice among the Aleuts, the skin boat predominated. The skin boat, also called a baidarka, was a kayak covered in sea lion skins. The baidarka was built using driftwood, and it contained one to three openings where people sat, one behind the other. The boat was propelled using a double-bladed paddle.

The Aleuts were extraordinary kayakers. They learned from an early age how to handle the skin boat in the wild and stormy sea. They were able to navigate by feeling the direction of the currents under their kayaks and the wind on their faces. They were so adept that they could kayak through blinding fog and in the darkness of night without losing their way.

They used their baidarkas to hunt for food in the ocean. Power and precision were required, which wasn’t easy to achieve in the rough and choppy open waters. Before the advent of guns, the Aleuts used a throwing board to hunt, which they called an atl-atl, in order to improve their speed and distance.

The atl-atl is a wooden board that is about a foot and a half long, depending on its owner’s hand size, that catapults darts and harpoons. One side of it is painted red, to lure the sea otter into striking distance, and the other side is painted black.

When the men spotted a sea otter, they would form a circle around it. They aimed their darts at the sea otter’s head because they didn’t want to tear its fur. Once the sea otter was hit with a dart, the hunter raised the throwing board and showed the black side to the other hunters. This was a signal of success and symbolized the color of the sea otter’s fur. The hunter whose dart was the closest to the sea otter’s snout was credited with the kill.

The Aleuts were expert fishermen and also hunted sea lions, fur seals, and walruses. In the eastern part of the Aleutians, certain men were chosen to hunt whales.

Map showing the Aleutian Islands

Whale hunting was a dangerous and prestigious profession, and many hunters died young. Usually, the father was a whale hunter and his skills were passed on to the son. They used a special poison on their spears, and when the whale was struck, they waited for it to drift ashore.

While standing on the bow of the schooner, seven-year-old Mike looked past the skin boats to the village of Attu. Salmon were hanging out to dry just outside the barabaras. These sod homes were built partially into the ground, and they provided shelter from the fierce storms and hurricane force winds called williwaws, which sound like a train roaring overhead. Williwaws plague the Aleutians all year long.

The Aleutians are synonymous with relentless bad weather. A semipermanent low pressure system, called the Aleutian Low, hovers over the Aleutian Islands. Cyclonic disturbances form when moist warm air, called the Japanese Current, flows from the tropics and collides with the cold air from the Arctic, spawning thick, icy fog and violent storms. As the Earth rotates, these storms move from west to east, affecting the weather in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest.

When Mike finally went ashore that day, the sand felt like powder on his bare feet.

Captain Somerville co-owned a fox fur farm and managed the trading post on Attu. Trading posts were part of the Alaska Commercial Company, and they dated back to 1776. That was when Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia who also ruled Alaska, granted the company’s trading rights.

Trading posts were set up throughout Alaska, and people traded furs, gold, walrus tusks, handwoven baskets, and other valuables for store-bought merchandise. Cash was seldom used. In the Aleutians, people relied on the trading posts for luxuries such as coal, lumber, flour, sugar, tea, and tobacco, to name a few.

Attuan boys with Arctic blue foxes

Mike lived on Attu with Captain Somerville for four years, until the captain moved back to Unalaska. Mike chose to stay in Attu, and Attu chief Mike Hodikoff and his wife, Anecia, adopted him, happily making him a part of their family.

Chief Mike Hodikoff (left) and his son, George

But today, nineteen years later, Mike couldn’t shake his feeling of doom, even as he made his way through the picturesque village of Attu, which he and forty-three others called home. As he passed the nine wooden cottages that had replaced the barabaras, he could smell the salmon cooking for dinner as its aroma wafted through the smoky stovepipe. Mike could hear the rhythmic sound of the gas motors in the power plant that gave electricity to the nearby schoolhouse.

When he saw his neighbor John Golodoff, he smiled warmly and stopped to talk with him.

“Are you going out with your father tomorrow?” said Mike in the Aleut language.

Although most Aleuts could speak English and many spoke Russian, too, the Aleut language was their mother tongue, which had three different dialects depending on where in the Aleutian Islands you lived. English was taught as a second language in school.

“I will be out tomorrow if the weather keeps like this,” said John.

Even though the Attuans’ cottages were well maintained and most had the modern convenience of running water, none had electricity or refrigerators. They used cellars to store dried and salted meat, and the Attuans regularly hunted, fished, and gathered fresh food.

June was the perfect time of the year to find seagull eggs. Their nests could be found on grassy hillsides and on sea cliffs. The Aleuts fearlessly climbed the steep and jagged cliffs or dangled from a rope to collect eggs to cook and eat.

Birds are plentiful in the Aleutians, with over five million flying around and roosting. Besides seagulls and ducks, there are puffins, storm petrels, ravens, sanderlings, sand pipers, bald eagles, geese, albatross, auklets, and murres. During the summer, all through the day and night, the birds can be heard calling out to one another as they sit on their eggs or care for their newly hatched chicks.

Surprisingly, however, the Aleutian Islands are treeless. This is a mystery that continues to puzzle scientists because the soil is rich and there are remains of a forest, which proves that at some point in time, trees flourished.

Since the Aleutians are treeless, wood is scarce. Lumber was imported, but the Aleuts also collected driftwood for their homes, boats, and tools. Because of this, they didn’t like to burn wood for fuel. Instead, they preferred to burn seal blubber in their lanterns and stoves.

As the sun shifted behind the mountain, a shadow fell on the bay, and Mike said good-bye to John. Before Mike went home to his wife and daughter, he saw Foster Jones come out of the small building that housed the power plant.

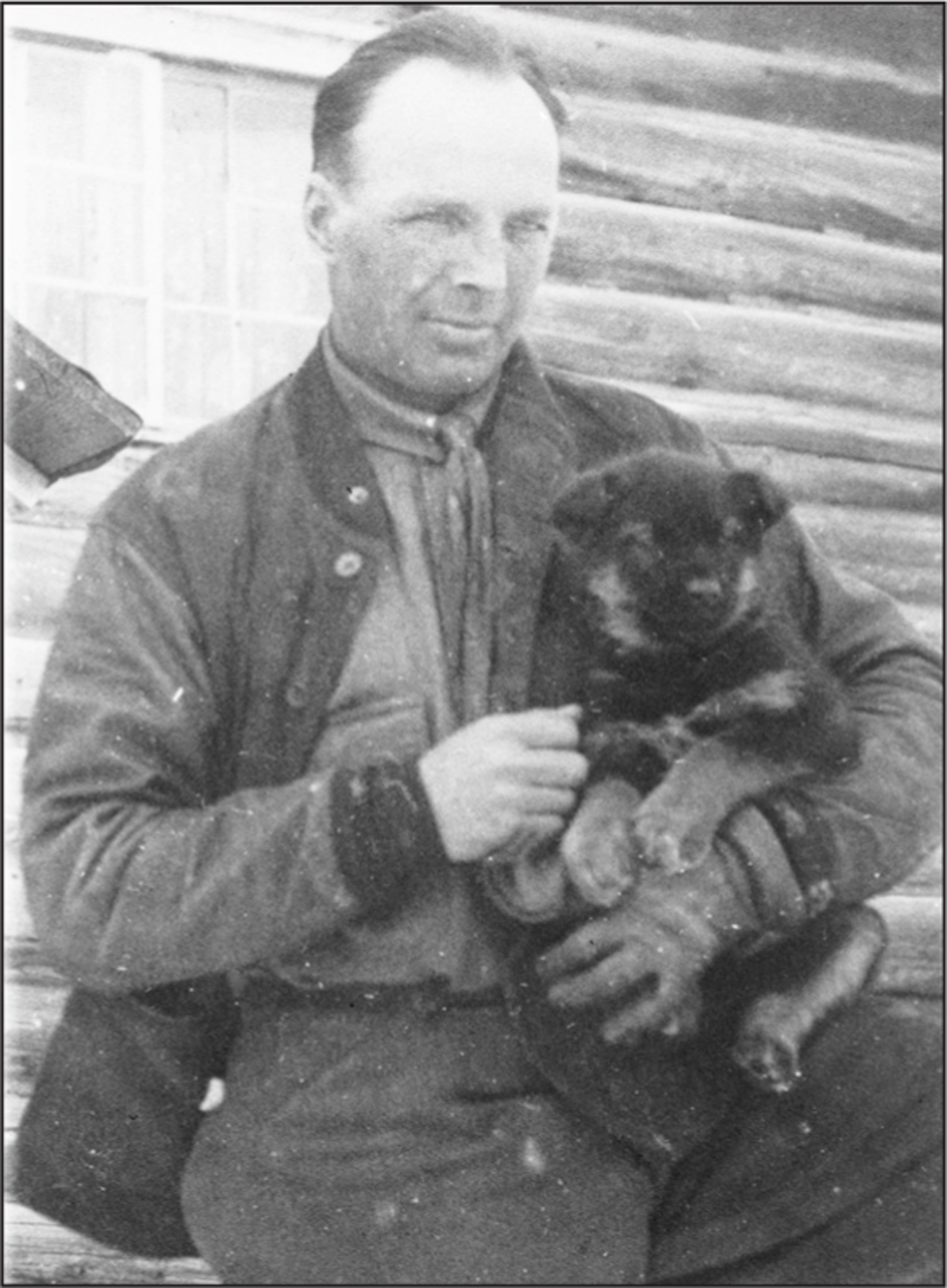

Foster and his wife, Etta Jones

Foster and his wife, Etta, lived in a cabin by the schoolhouse on Attu. They had moved to Attu in August 1941. Both worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the federal government agency created to protect the welfare of American Indians and Alaskan natives, including the Aleuts and Inuits (also known as Eskimos). The BIA’s services included managing the school system, and this involved sending teachers to the villages.

Attu schoolhouse

Etta, who grew up in Connecticut, was Attu’s schoolteacher and nurse, and Foster, who was originally from Ohio, was Attu’s radio operator.

Since there were no phones on the island, the radio was the only communication link to the outside world. It was Foster’s job to send weather reports four times a day to the naval radio station 770 miles away in Dutch Harbor, and this two-way radio communication was how he learned that the Japanese had bombed the navy and army installations at Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island just three days ago.

It was also Foster’s job to report any sightings of Japanese ships. If anyone saw one, Foster was to use the code words, “The boys went out today but didn’t see a boat. They came home and went to eat fried codfish.”

But so far, no one on Attu had seen any.

The only report Foster made was to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He told them that every day on the radio he heard Tokyo Rose, a Japanese radio announcer known for spreading propaganda, say, “Attu, we are coming.”

Just a few weeks ago in May, the navy had tried unsuccessfully to evacuate Attu. The choppy sea and stormy weather made it too dangerous and difficult. The navy promised to come back for them. No one knew when that would be, but everyone on Attu had packed their belongings. They were ready and waiting.

Early the next morning, on June 7, 1942, a ship was spotted just outside the harbor. At first, it was hard to tell through the heavy fog if the ship was American or Japanese. There weren’t any flags flying to give an indication.

“We had noticed the big ship anchored outside the harbor,” said Etta. “But, of course, had thought it was our own.”

When the ship finally raised its flag, there was no mistaking it — the red rising sun against the white background. Their worst nightmare had come true. The Japanese soldiers had arrived.

“On Sunday morning [June 7] a little after eleven we were all coming out of church when we saw them [the Japanese] coming out of the hills. So many of them,” said Attuan Innokenty Golodoff. “Twenty came down. We had no knives, no guns, no nothing. The batch had no boss. They were young and they shot up the village. They hit Anna Hodikoff [Chief Mike Hodikoff’s sister-in-law] in the leg. The second bunch came and told them to stop. I saw one of their own men dead by the schoolhouse. They must have shot him.”

At first, the Attuans wanted to grab their rifles and fire back.

“Do not shoot,” said Chief Hodikoff. “Maybe the Americans can save us yet.”

While the Japanese soldiers fired bullets through the windows and walls of their home, Foster Jones sat at his radio and transmitted a message to the navy listening post in Dutch Harbor that the Japanese were attacking. Etta threw all of their letters and reports into the fire that was burning in their fireplace. When the bullets died down, Foster went outside their home and surrendered to the Japanese.

A Japanese soldier stormed past Foster and held a bayonet against Etta’s stomach.

“How many have you here?” demanded the Japanese officer.

“Two,” said Etta. “How many have you?”

“Two thousand,” he said.

The Japanese soldiers quickly rounded up the Attuans and herded them into the schoolhouse.

When Mike walked into the schoolhouse, he said hello to Foster, but a Japanese guard ordered him not to speak.

“Well, Mike,” said Foster, disobeying the guard. “The world has seemed to change today. We are under Japanese rule now.”

At that moment another Japanese guard came into the schoolhouse with the American flag. A Japanese flag now flew in its place.

A proclamation in Japanese was read by a military police (MP) officer, and a Japanese interpreter named Karl Kaoru Kasukabe translated it into English for them.

“An officer showed us how to bow to the emperor and also to the Jap[anese] commander,” said Etta. “Mimeographed sheets were distributed to all of us, which gave the rules of occupation. The natives, the sheet said, were to be freed from United States ‘tyranny.’ No harm was intended, and we were to go ahead with our way of life as if nothing had happened. But we were to pay strict attention to any orders issued by the Jap[anese] commander.”

What the people of Attu didn’t know was that the Japanese interpreter, Karl Kasukabe, had spent his childhood in the United States, where his sister, Mary, and his father still lived. His father had helped build the U.S. railroads and was now a farmer in Pocatello, Idaho, a small town.

When Karl was a teenager, his mother abruptly pulled him out of school and took him and his sister and brothers back to Japan. She was upset about the “democratic education” Karl was receiving in America. His parents viewed democracy as having the freedom to do what you want. They wanted Karl to have a “monarchy education” in Japan, where children learned to be loyal to the emperor, dutiful to their parents, and obedient to and unquestioning of authority.

His parents would soon find out that it was too late for their eldest son. When Karl was enrolled in a Japanese high school, the military officer assigned to the school deemed Karl “an undesirable student” because of Karl’s democratic and liberal ideas. The military officer punished Karl by disqualifying his military drilling credit, effectively denying him a college education and regular employment.

Through sheer grit and hard work, Karl managed to become qualified as a first class military interpreter in English and a second class military interpreter in Russian. He also maintained a job in the Mitsubishi factory where the infamous Zero fighter plane was manufactured. When the Japanese went to war with America, Karl’s job as an interpreter brought him to Attu.

After Karl finished translating the proclamation and a speech from the officer in command, none of the captured Americans said a word. With the exception of Foster and Etta, the Japanese told the Attuans that they could leave and go home. It was nine o’clock at night, and no one had eaten or had anything to drink all day. They found their homes looted and pockmarked with bullet holes.

Just as Mike was sitting down to have some tea with his wife, Parascovia, and baby daughter, Titiana, a Japanese soldier came in and ordered Mike to come with him.

Mike and his neighbor, Alex Prossoff, were taken back to the schoolhouse, where Karl was waiting for them and carrying a sword. Karl warned Mike and Alex not to speak to the Joneses, and he ordered them to help Foster and Etta move their possessions out of their nearby cabin. The Japanese soldiers would now be living in the Joneses’ home.

While gathering their things, Foster and Etta tried to take some food with them. This angered Karl.

“I was beaten with the butt end of a rifle and struck across the back by a Jap[anese] soldier who had been acting as an interpreter,” said Etta. “He knocked me down, stepped on me, and kicked me in the stomach. Then I saw him hit my husband and knock him down.”

Karl slapped Foster on the face, knocked him down, and kicked him. Then Karl picked him up, slapped him, knocked him down again, and kicked him out the door.

Mike couldn’t stop shaking as he and Alex helped carry Foster and Etta’s things to an abandoned house. On the way, he found a shoe that belonged to Etta stuck in the mud. Afterward, Mike ran home. He stood outside the door to his house for a few minutes, trying to calm his uncontrollable shaking.

“I didn’t want to scare my wife,” said Mike. He couldn’t help but think that if it happened to Etta and Foster Jones, it could also happen to him and his family.

That night Mike barely slept. There was constant noise from the firing of Japanese machine guns.

Early the next morning, Japanese soldiers came and took Foster away. They believed he was an American spy, working in conjunction with the Russians. Russia was only 765 miles away and an ally of the United States. The Japanese feared that the Russians would attack them while they occupied the Aleutians, and this threatened their plans to expand Japan’s empire.

Hours later the Japanese guards came for Etta. They took her to a room where she saw the body of her dead husband. Shocked and horrified, Etta could barely stand up as they marshaled her back to her room.

Soon after, Karl came to Mike’s door.

“Mr. Foster Jones is dead,” he said to Mike.

He ordered Mike to come with him to the house where Foster’s body lay. It was there that Mike met another interpreter, named Mr. Imai.

“He said Foster cut his own wrist with his pocketknife,” said Mike.

Mike thought it was strange that after the Japanese captured Foster they would allow him to keep his pocketknife, but he kept his thoughts to himself.

Karl and Mr. Imai called Mike into the room, where he saw Foster’s dead body.

“He was wrapped in a blanket,” said Mike. “They told me to bury him without a coffin. So I dug a grave by our church.”

Later, Mike whispered to Etta that he had buried Foster near the church.

A few days later, Etta was ordered to board a Japanese ship. Before she left, Karl Kasukabe stopped her.

“He shook my hand,” said Etta, “and apologized, and said he was following the commander’s orders.”

That was one of Etta’s last memories of her life in Attu.

The Attuans would not see Etta Jones again.

For the next three months, the Japanese lived with the Attuans on the island. Just a single strand of barbed wire was needed to keep the Attuans fenced in, because not only were there Japanese soldiers standing guard, but their camp also surrounded the village.

“They guarded our houses all the time,” said Innokenty. “We could go outside for fresh air but not away from the houses.”

The Attuans did not have much food, and they were forced to tear boards off their homes to burn for fuel.

The Japanese did allow them to occasionally go out and fish for food, but they were always accompanied by the Japanese interpreter, Mr. Imai, and they were required to fly little Japanese flags on their boat.

The ocean was filled with halibut, cod, salmon, poggy fish, and herring, and at low tide there was an abundance of clams and sea urchins. When the Attuans went out, they caught a lot of fish, but the Japanese made sure they remained hungry.

“The Japanese took most of our fish away,” said Mike. “We didn’t have enough fish for the whole village. All I had was one codfish left for myself.”

On September 14, 1942, a Japanese coal carrier arrived. The Attuans were told to pack their things — they were being sent to Japan.

“We tell them we didn’t want to go,” said Innokenty. “But they tell us we must go to Japan and promise us they will take us home again when the war is over.”

Mr. Imai kindly told them to pack as much food as they could because it would be scarce in Japan.

“So each family takes flour, sugar, barrels of salt fish,” said Mike. “We don’t know how we are going to live in Japan. So we take tents, stoves, fishnets, windows, and doors.”

“Everything except our homes,” said Innokenty.

It was after midnight when the Attuans went onboard the ship. The children were crying because they didn’t want to leave, but the Japanese soldiers picked them up and forced them down below with the others into the dark and stifling hold, where the coal had been stored.

“Everything was black and dirty,” said Mike.

What they didn’t know at the time was that this was a death sentence.