JULY 26, 1942. KISKA, ALASKA, FORTY-NINE DAYS AFTER THE JAPANESE INVADED ALASKA.

On the northwest coast of Kiska Island, Alaska, at Conquer Point, down a treacherously steep ravine of jagged volcanic rocks, a man with unkempt brown hair and a thick beard sat near a creek. He was desperately trying to write his name on his hunting jacket. It wasn’t an easy task.

The biting wind deadened his hand, making it difficult to grasp the dull pencil, which was all he had to write with. For a time, he had marked each day off by carving a notch up the side of the pencil, but somewhere along the way he had lost count. One thing he knew for certain, though, was that he was starving.

Every morning, as the morning fog clung to him, soaking his clothes and chilling his bones, but, more importantly, keeping him hidden from plain sight, he dared to venture out of the cave where he slept. He trekked down the rocky ravine in his rubber-soled boots to the creek, where he dipped the hood of his jacket into the ice-cold water for a drink.

Today, however, something unexpected happened. As he was walking to the creek, he suddenly fainted. When he finally regained consciousness, he knew he had a life-or-death decision to make. But first he needed to write his name on his jacket.

His canvas hunting jacket was tattered now and didn’t keep him warm in the wet, windy, and foggy Aleutian weather, but he was forced to make do with what little he had. When he finally finished writing out his full name, he looked it over to make sure it was legible. It read: WILLIAM CHARLES HOUSE.

He actually went by the name Charlie, but it was important that his entire name was clearly written. This way when his dead body was found, it would be easy to identify him.

It had been sixty-nine days since Charlie had first arrived on Kiska on May 18, 1942, and it was the luck of the draw that the navy assigned him there. Charlie was an aerographer’s mate first class, also known as an aerologist or weatherman. On Kiska, he was in charge of the weather team that was made up of nine other men and one mascot, their dog. The weather station on Kiska was to be one of four weather stations set up on the Aleutian Islands during World War II. The others were to be located on Atka, Attu, and Kanaga.

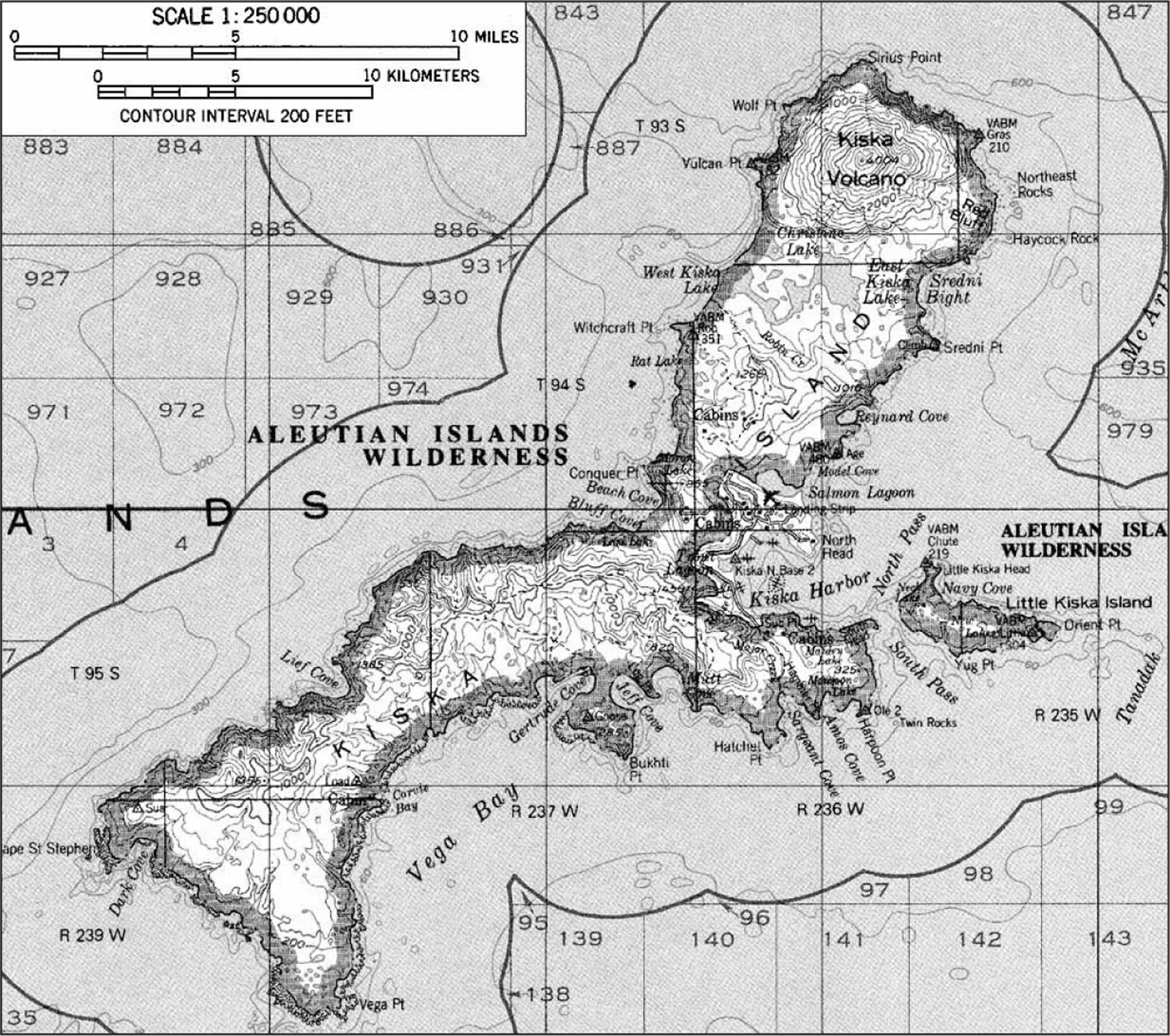

Map of Kiska

The four men who would lead the weather teams randomly picked their assigned location by drawing slips of paper out of a hat. Charlie happened to pick Atka, but when fellow aerographer Ed Hudson asked him to switch and go to Kiska, Charlie agreed. At the time, no one suspected the life-threatening ordeal that was about to descend on Charlie and his weather team.

It was imperative for the military to set up weather stations in the Aleutians. The weather was top secret information. During the war in the Pacific, the weather reports from the Aleutians were crucial to strategic military operations. The weather forecast determined when the military would attack the enemy. Since weather systems move from west to east, the Japanese knew what the weather was like before the Americans, and they used it to their advantage. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military hid their fleet behind a storm front that was heading east toward Hawaii. This strategy allowed the Japanese fleet to remain undetected by American scouting planes and ships.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the ships in the Pacific maintained radio silence so the enemy would not know their location and bomb them. Since the U.S. military could no longer rely on these ships for daily weather reports, their attention turned to the Aleutians because these islands are the westernmost part of the United States.

However, the weather was difficult to predict in the Aleutians and was accurate only 60 percent of the time, because the cold air from the Arctic clashed with the warm air from the Pacific, creating the sudden and violent williwaws. Also contributing to the difficulty in predicting the weather were the weather instruments available at the time. Unlike today, during World War II, there were no meteorological satellites circling the earth, feeding weather data into computers, and creating weather forecast models, which, in turn, make such accurate weather predictions that the computer can pinpoint the time of day it will start to rain.

Pilots gathering in the weather station before taking off from Dutch Harbor

Instead, they relied on people like Charlie and his weather team who read instruments, took measurements, made observations, coded the results, sent the ciphers over the radio, deciphered incoming codes, and mapped and shared their weather information with other weather stations. The weather teams had specific codes for various weather conditions and they used these weather codes to communicate with one another. They used a secret radio transmission code book that was given to them each month to cipher and decipher the weather codes. The ciphered weather reports were transmitted at scheduled times, several times a day, at weather stations set up all over the world.

The weather teams used several instruments to take surface weather readings, such as a thermometer to check the temperature, a barometer to check the air pressure (low pressure means bad weather), an anemometer to measure wind speed and direction, and a rain gauge. They also studied aerology, the branch of meteorology that pays particular attention to the upper atmosphere because this is where the weather changes occur before they are evident on the surface below. Some aerographers also used robot weather balloons to make weather observations in the upper atmosphere.

Aerologists used this information to make predictions of the wind direction and velocity before it occurred at various altitudes. Airplane pilots relied on this information, as did the navy’s underwater and aircraft carrier operations, since an aerographer could forecast the surf conditions and determine how the wind would affect the surface waves. If the aerologist reported that the surf was high and the waves were rough, then an underwater attack would not be planned for that day.

But Charlie and his weather team didn’t use weather balloons. Instead, they were working on a top secret mission. To this day, the weather team’s exact mission is still a secret, but it is believed it had something to do with the antennas they were installing on Kiska and possibly radar, which was an emerging technology. Nevertheless, what is known for certain is that keeping their mission secret from the enemy would cost them dearly.

When Charlie and his nine-man weather team were dropped off at Kiska, they occupied three shacks with electricity and heating supplied by aboveground oil tanks. The shacks were interconnected by wooden sidewalks.

The powerhouse was in the middle, and it contained the electrical generator and weather laboratory with all of the weather measuring instruments. The aerographers slept here in iron bunk beds.

The cookhouse was on one side, and it had a stove and a walk-in refrigerator that stored their six-month supply of food, which included half a cow. Meals were served there twice a day by the cook and his assistant, who slept there.

The third building was the radio shack, from which the radiomen sent the coded weather reports to the navy command in Dutch Harbor. They also slept here.

No one else lived on the 110-square-mile island. The closest village was on Attu, which was 180 miles northwest, and the only time the Aleuts came to Kiska was during hunting season when they trapped blue foxes.

The weather team was isolated and alone with the exception of a sociable and intelligent two-year-old black-and-white shorthaired shepherd dog named Explosion. Explosion got his name when he was born during an accidental dynamite explosion at Dutch Harbor. He was the runt of the litter, and Ensign William C. Jones brought Explosion to Kiska when he helped the weather team install the radio station. Before he left, he gave them Explosion as a mascot.

Explosion was everybody’s friend, and he was allowed complete freedom on Kiska. He would roam the area and run in and out of the three shacks whenever he pleased, and he always enjoyed a good game of fetch. Explosion also liked to follow the team around while they worked. When it came to bedtime, Explosion slept beside whoever threw a blanket on the floor for him.

Kiska weather team: Front row (left to right): John McCandless, Robert Christensen, Walter Winfrey (holding Explosion), Gilbert Palmer, and Wilford Gaffey. Back row (left to right): James Turner, Rolland Coffield, Charlie House, Lt. Mulls (not present at the time of the attack), Lethayer Eckles, Lou Yaconelli (not present at the time of the attack), and Madison Courtenay

Kiska was supposed to be the weather team’s home for several years. But then something happened on May 24, 1942, that would change everything. Just six days after Charlie first arrived on Kiska, he saw a plane fly overhead.

Although everyone was trained to spot enemy airplanes, they weren’t always easy to recognize, especially when the Japanese painted their planes to look like American ones. So the silhouette of the plane was used to spot the specific characteristics, such as the wingspan, the shape of the wings, the look of the nose, the shape of the fuselage, the shape of the tail, and the profile of the cockpit.

After studying the silhouette, the weather team checked the Enemy Plane Identification Book. It was definitely a Japanese plane, specifically a Type 97, Yokosuka reconnaissance seaplane, code name Glen.

They immediately radioed Dutch Harbor with the news, but Charlie was unprepared for their response. The Dutch Harbor radio operator asked Charlie if he was sure he’d really seen an airplane. Charlie thought it was a ridiculous question and didn’t bother to reply.

Instead, the weather team began to work feverishly, preparing for a possible attack. Since they were on their own and basically defenseless, they started to dig zigzag trenches to shield themselves against bombs and machine-gun fire. Hidden away from their main camp, they pitched tents and stashed food and ammunition in case their three shacks were destroyed.

Ten days later, Charlie awoke to the radioman screaming, “Attack! Attack! Attack!” He was spreading the news that the Japanese had bombed Dutch Harbor the day before, on June 3, 1942. The weather team tried and tried to radio Dutch Harbor for more information, but they couldn’t get through.

After three nights of sleeping fitfully in their clothes with their guns by their sides and calculating the position of the Japanese fleet using a ten-knot speed, they assumed it was a safe bet that the Japanese weren’t anywhere near Kiska. Everyone felt a sense of relief and looked forward to some much-needed sleep.

That night Charlie undressed and fell fast asleep in the lower bunk. It was around two A.M. on June 7, 1942, when he was startled awake.

“Attack! Attack!” Walter Winfrey screamed from the top bunk.

“Go back to sleep and quit your yelling,” Charlie said. “It’s not time to get up. You’re just having a bad dream.”

Walter turned on the lights. “Then what am I doing with this bullet hole in my leg?”

Charlie looked at the machine-gun bullet hole in Walter’s right leg. He was wide awake now as the rat-a-tat of machine guns shattered the glass windows. They dropped to the floor and dressed quickly. At the sound of the guns firing, Explosion the dog started barking wildly. Charlie pulled on his boots and slipped on his hunting jacket as bullets continued to tear through the shacks.

From the bedroom, they hurried into the aerological room, where they found aerographer James Turner turning the stove on high heat. He and Charlie wasted no time burning the top secret code books.

“Do you have the weather ciphers?” Walter shouted to James.

“No!”

Dodging bullets, Walter crawled under the machine-gun fire and grabbed the weather ciphers. He threw them to James. The top secret ciphers were thrown into the fire.

Meanwhile, a bullet ripped clean through radioman Madison Courtenay’s hand when he turned on the transmitter to send a report announcing the Japanese were invading Kiska. Since it would take five minutes for the transmitter to warm up, Madison ran into the bedroom to make sure everyone was awake. As he tried to get back to the transmitter, he became trapped by machine-gun fire. It was impossible to send the report, and the transmitter was quickly shot full of bullets and destroyed by the Japanese machine guns.

When the code books and ciphers were finally burned to ashes, James grabbed his rifle and crawled outside behind the radio shack. Suddenly, the machine guns stopped firing. Charlie grabbed two gray blankets and ran out the door. At first, they couldn’t see anything.

What the weather team couldn’t see was Captain Takeji Ono of the Japanese Special Naval Landing Force and his 1,250 Japanese soldiers. They had arrived at Kiska about an hour ago and 3,750 more Japanese troops were on their way.

The weather team and Explosion took cover behind a pile of lumber behind the cook shack, but the other shacks were blocking their view of the enemy’s whereabouts. They quickly decided to run up a ravine west of the three shacks to where large rocks and low clouds would give them cover.

But as they ran up the hill, flaming tracer bullets the size of baseballs were fired at them, forcing them to drop to the ground. When the coast looked clear, they would get up, run, and dodge more flaming tracer bullets. After running the length of three football fields, they reached the ravine and were hidden in the fog.

“Get out of here, keep under cover, and spread out,” yelled James Turner and Gilbert Palmer, who were firing their rifles and covering the men’s retreat.

Charlie went to the right with his gray blankets over his shoulders. That was the last time he saw his weather team.

He ran until he was so overwhelmed with exhaustion he was forced to rest. He was lying flat against the ground when he heard footsteps in the distance. He pressed his ear to the ground and listened hard. He could hear the stomping beat of the Japanese soldiers’ boots closing in on him. After a moment, relief washed over him when he realized it was just the pounding of his heart. His mind then kicked into overdrive as he determined his next move.

Unarmed and alone in the fog and darkness, Charlie reasoned the Japanese would leave after they destroyed the weather station. That wouldn’t take them long. Charlie’s goal was to avoid capture by the Japanese. With the sun beginning to rise, he found some gray rocks and covered himself with the two gray blankets, camouflaging himself from the enemy.

Then he waited, and waited, not moving an inch. He could hear the engines of planes flying overhead and guns firing, and it was one of the longest and loneliest days in his twenty-nine years. Charlie felt as if his whole world had just been ripped out from under him.

During the month of June in Alaska, the days are long, with sixteen and a half hours of sunlight, but the fog in the Aleutians is almost always present. When night finally came, Charlie decided to make his move. His mission was to get to the tents where he and the weather team had stored their food, weapons, and ammunition. The tents were located in a ravine about two miles away.

As Charlie hurried over the rough terrain, he became overheated. When he came upon a creek, he stopped and greedily drank the cold water, and when he passed a snow drift, he packed the icy snow into his mouth. This caused him to become nauseated, and he threw up his last meal.

By the time he’d searched the area several times, the sun was beginning to rise in the east, and he still couldn’t find the food and ammunition. Charlie decided to cross a stream, but he lost his balance and fell into the icy water. He was soaked and freezing cold. He was now at risk for developing acute hypothermia, and if he went into shock, he would die.

Fortunately, it turned out to be an unusually sunny day on Kiska, and Charlie laid his wet clothes out on the grass to dry. About the same time, a Japanese patrol boat pulled in and dropped anchor offshore. Charlie was in plain sight and didn’t dare move.

He camouflaged himself again by covering up in the gray blankets and lying low in a creek ravine. That night he moved to a small meadow that had a view of Kiska Harbor. Although this position allowed him to keep an eye on the Japanese and would let him see when they left, it also made him visible. So he slept during the day on gray rocks covered by his gray blankets and only moved when it was dark. This strategy kept him well hidden from the Japanese.

After two days of not eating, Charlie couldn’t stop thinking about food. He knew he wouldn’t be able to find the food stashed in the tents, but he remembered one piece of advice from a fur trapper he’d met in Dutch Harbor. “There’s nothing poisonous growing in the Aleutian Islands,” the fur trapper had mistakenly told him.

Trusting that the fur trapper was right, Charlie picked what the Aleuts called pootchki, or wild celery, not knowing its leaves were poisonous. The tiny hairs on the stem are oily, causing rashes and blisters to break out on the skin and lips, which can last for weeks. When Charlie took his first bite into the stem, he didn’t like the taste. It was bitter. So he tried peeling away the outer skin and discovered the inner flesh of the pootchki tasted like fresh corn on the cob. Luckily, he never ate the poisonous leaves.

A few days later, hidden by the shadows of the night, Charlie moved away from the small meadow where he had been hiding. His decision to move was easy after he had nearly been hit by bursting bullet shells from the antiaircraft guns. The American airplane pilots had been busy bombing Kiska two to three times a day, trying to force the Japanese to leave.

A Japanese tank crew on Kiska

But the Japanese had no intention of leaving Kiska. While the U.S. government was trying to keep the Japanese invasion of Kiska and Attu a secret from the American public, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters was trying to keep their defeat at Midway a secret from the Japanese public. To boost the public’s morale, they spread the news about their capture of Kiska and Attu. The news also spread to the American public through Radio Tokyo broadcasts, which were reprinted in the American newspapers and magazines.

The Japanese radio broadcasts announced that Attu and Kiska were now part of the Japanese empire and had been renamed. Attu was now called Atsuta Island, after the Atsuta shrine at Nagoya, Japan. Kiska was now known as Narukam, derived from Narukamizunei, one of the Japanese names for June.

The Japanese media also reported that the soldiers and their equipment had been meticulously selected, and they had brought large quantities of seeds and potatoes with them to plant gardens.

However, after forty-eight days on Kiska, the Japanese were suffering from loneliness.

“The loneliness in this remote northern base is hard to imagine,” a Japanese correspondent reported. “We have received no letters or comfort bags yet…. Eating is our only pleasure. In September we will have the bitter cold Arctic winds and in the winter snow and sleet. The soldiers are all in high spirits as I watch them busily at their work, but I imagine they, too, are lonely, for loneliness is loneliness and hardships are hardships to anyone.”

Like the Japanese soldiers, Charlie was suffering from loneliness and hardships, but he was also dying slowly from hunger despite spending his days eating pootchki and earthworms. He also spent a lot of his time trying to stay warm to ward off hypothermia, and he discovered that the dry grass was good insulation. He layered two feet of grass on the ground, then folded his blankets over it and covered them with eighteen more inches of grass. He would crawl in between the blankets, and the haystack of grass would keep him warm and dry, even if it rained directly on it.

Charlie spent his days thinking. He worried about his wife, Marie, and their baby daughter, Barbara, wondering if he would ever see them again. He dreamed about eating cheeseburgers, french fries, and apple pie and wondered how he was going to get out of this situation alive.

Since the beginning, he’d counted on the Americans invading Kiska and driving out the Japanese, but that now seemed unlikely to happen anytime soon, and Charlie was literally running out of time.

The human body can starve to death in eight weeks, and in the final stages of starvation, a person can suffer from hallucinations, convulsions, muscle pain, and heart palpitations. After seven weeks on a diet of plants and worms, Charlie only weighed eighty pounds, having lost a hundred. If he continued to evade the Japanese, he would most certainly die, but if he surrendered to the Japanese, there was a good chance they would execute him.

There was only one possibility of survival. The next morning, on July 26, 1942, Charlie started to climb the steep hill, but he was too weak and kept falling down and fainting. He thought he might die, but by sheer will he reached the summit by midmorning.

Patchy fog swirled through the tall grass and kept Charlie hidden from the Japanese soldiers who were standing by and pointing their antiaircraft guns toward the sky. After writing his name on his jacket, Charlie ripped a piece of his white undershorts. Feeling shame and humiliation, he marched toward the Japanese soldiers, waving the piece of undershorts as a surrender flag. Charlie feared for his life.