JULY 26, 1942. KISKA, ALASKA, THE DAY CHARLIE HOUSE SURRENDERED TO THE JAPANESE.

When Charlie walked toward the Japanese soldiers, they saw a ghost in the fog. His eyes protruded from his skull and his cheeks were hollowed out. His clothes hung loosely from his skeletal body.

Charlie could barely stand after the long walk. The Japanese soldiers rushed toward him, held him up by his elbows, and then immediately sat him down and fed him biscuits and tea.

As Charlie ate, a group of American B-17 bombers flew overhead, and the Japanese began shooting at them. After dropping their bombs, the planes flew away, and the Japanese officer in charge came over to Charlie.

He was angry and yelled orders at some of the soldiers. Charlie didn’t understand what was being said, but he had serious misgivings when they adjusted their bayonets in their sheaths and the officer motioned for Charlie to follow him down a path.

The thought of getting slaughtered by the bayonets weighed heavily on Charlie’s mind, but he somehow summoned the courage to follow. After a short walk, Charlie saw where he was being led and was shocked.

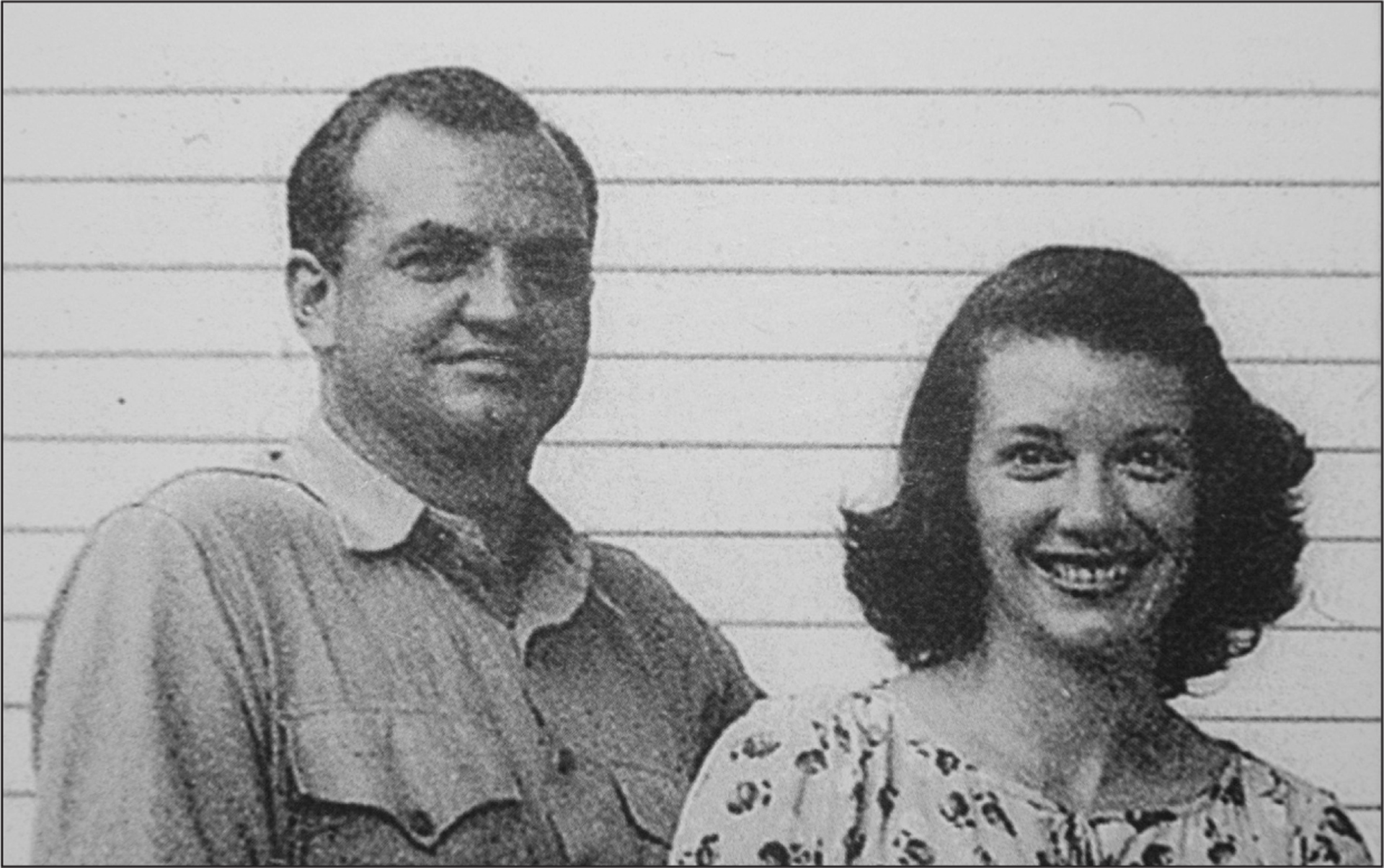

Photo of Charlie House and his wife, Marie, that he carried in his pocket while a POW

He was right back where he started forty-nine days ago. Not only could he see the three shacks where his weather team had lived, but there were now another twenty-four structures that the Japanese had built.

Despite the ankle-deep mud and continuous bombing by the Americans, the Japanese had managed to install telegraph and power poles, fire hydrants, and a defensive fortification. They had also built roads, three power plants, and a water storage tank. Plus, the camp headquarters not only had a seaplane and submarine base, three radio stations, and a telephone system, but also a newly dug network of hillside tunnels. These tunnels protected them from the daily American bombardment, and also housed the hospital and sleeping quarters. Outside, the Japanese had planted gardens and built six Shinto shrines.

A glimmer of hope lifted Charlie’s spirits. “I had the feeling of being spared again,” he said.

They sat Charlie down on a grass sack, and a circle of Japanese soldiers stood around him and just stared. They were surprised and in utter disbelief — but mostly impressed — that he had managed to survive the unforgiving Aleutian wilderness. They had been certain he had succumbed to death weeks ago.

The soldiers immediately gave him some dinner, tea, and more biscuits. While he ate, the Japanese soldiers continued to stare, and stare. They stared at him for several hours.

“I had the feeling of a monkey in a zoo,” Charlie said.

In the evening, they gave Charlie a grass sack and some blankets. They had him sleep in the powerhouse shack, the same place where he and Walter were shot out of bed. As Charlie lay down to rest, he could see the Japanese soldiers peeping through the window. A long line formed as each soldier stared at Charlie for a minute, then gave the next soldier in line a turn to take a look at him. It wasn’t until darkness fell and it became hard to see that they stopped staring.

Charlie could hear the rain tapping on the asphalt roof. It had rained every day but one since the Japanese invaded.

“It sure felt cozy to have shelter again,” Charlie said.

That night, a Japanese guard shined a flashlight into Charlie’s eyes every half hour to make sure he was still alive. The next morning, Captain Kanzaki brought war correspondent Mikizo Fukazawa to see Charlie so he could write a story for the Japanese newspaper Domei. That’s when Charlie found out the fate of his nine-man weather team.

When they entered the room, Charlie kicked away his blankets and sat up. Mikizo noticed right away that Charlie had “the friendliest of smiles” although his salute, which he was now required to do to show his respect to the Japanese officers, was a little shaky.

“His eyes were unnaturally large in contrast to his sunken cheeks,” Mikizo said. “And his emaciated limbs were so thin they were like sticks.”

“When our detachment launched the surprise attack on Kiska Island, there were ten American soldiers stationed on the island,” Captain Kanzaki said. “We managed to capture nine of them, but we couldn’t track down the tenth. Finally, we decided that he had probably perished from the cold or from hunger somewhere in the mists and called off the search…. This was the man we sought.”

In the Japanese hunt for the ten-man weather team, Rolland Coffield, the chief pharmacist (or medic) and John McCandless, the cook, were the first two captured, just a few hours after the Japanese landed on Kiska. Although Rolland and John were well hidden in the fog, so were the Japanese, and the two ran right into Japanese soldiers.

The soldiers confiscated their weapons, tied their hands, and pointed their bayonets at them. Under interrogation, John and Rolland were asked how many men were on Kiska, what kind of weapons they had, and where they were hiding. Then they were forced to cook some food from their icebox and eat it to show the Japanese it wasn’t poisoned.

The next to be captured were James Turner, Lethayer Eckles, and Gilbert Palmer. They had spent the night in an abandoned Aleut barabara. On the second day, when they were trying to figure out how to get to their food stash and an abandoned dory, the Japanese spotted them hiding in the tall beach grass. The Japanese soldiers surrounded them, took their rifles, and searched them. James was singled out. The soldiers took him into a small office where there were about six more officers. Two of them beat and slapped him because they thought he was rude and disrespectful, but they also beat him because they thought he was withholding information, which he was. James wasn’t about to tell them what the antennas were for.

“I told them all I knew was the weather and very little of that because I hadn’t been there very long,” James said.

The Japanese wasted no time putting the captured men on a cargo ship the next day and sending them to a prison camp in Japan. They would arrive in Yososuka ten days later, on June 19, 1942.

The remaining members of the weather team, Walter Winfrey, Robert Christensen, Madison Courtenay, and Wilford Gaffey, also surrendered to the Japanese. They lasted a week in the unforgiving Aleutian wilderness, finding shelter in abandoned barabaras. Each barabara had some food left behind by the fur trappers, and they also foraged for mussels from the rocks and collected driftwood near the shore. Their dog, Explosion, also inadvertently helped out by cornering a blue fox and tussling with it until Wilfred stepped in with a club.

“That night we had fox stew,” Walter said.

On June 13, 1942, the last day of the Kiska Blitz, and two days before they surrendered, the four men watched as a PBY flew in and dropped a bomb on Vega Bay, about a thousand yards from where they took cover in a shallow ravine.

Explosion was at his wit’s end with all of the noise from the machine guns and bombs. He had a habit of running around willy-nilly and barking like crazy at the sound of gunfire, but if they wanted to stay safe, they needed to be quiet and still. So Walter lay on top of Explosion and muzzled him.

When the bombing and machine-gun fire stopped, they made their way back to a barabara in Gertrude Cove. They stayed there for two days but they were running out of food.

“By that time the fox stew was at an end,” Walter said. “It tasted pretty bad even though we were starving.”

Their hunger pangs prompted them to backtrack from their current camp to look for the food cache in a barabara on Sand Beach. They knew that the fur trapper had left behind a supply of food that would last six months if they rationed it carefully.

They hiked over the mountains for five hours. With each step Walter took, he was reminded of the bullet lodged in his leg, but he ignored the pain. He had no choice if he wanted to survive.

When they arrived, it was a “bitter disappointment,” Walter said. The Japanese soldiers had destroyed the barabara and taken all the food.

They started hiking back to their camp at Gertrude Cove, making it halfway up the mountain before it started to sleet. They were wet, cold, hungry, and exhausted from walking against the powerful Aleutian wind.

“We could have never made it,” Walter said. “So the only other alternative was to turn [ourselves] in to the Jap[anese] and take our chances or starve in the hills.”

They threw down their rifles and ammunition, and at 5:30 P.M. on June 15, 1942, eight days after the Japanese invaded Kiska, Walter, Robert, Madison, and Wilford found some Japanese soldiers working on the beach and surrendered.

“Guards came running from all over,” Walter said.

They were taken to their former cookhouse, and one of the first questions they were asked was where was Charlie House.

“We told them we believed he was dead,” Walter said.

The men were fed rice and soup that night, and the next day they were interrogated. They were asked if the bay was mined, if there were any more food stashes, and where was Charlie House. Again, Walter told them he thought Charlie was dead.

When Walter told them about the bullet that was still in his leg, the Japanese officer seemed “greatly concerned” and called in the doctor.

The doctor gave Walter a shot of Novocain, removed the bullet, carefully stitched the wound, and bandaged it.

The following night, they were put on an old coal-burning transport ship heading back to Japan. When they arrived, about June 27, they were blindfolded and taken to a navy base and kept there until Walter’s bullet wound healed. On July 2, 1942, the men were transferred to Ofuna interrogation camp, one of the worst prison camps in Japan.

After Charlie heard the news that his team was captured but still alive, a Japanese doctor bustled through the door.

“He’s had hardly anything to eat for over fifty days, except for the grass growing on the shore,” Captain Kanzaki told the doctor. “When we gave him some rice gruel, he gulped down so much he got sick.”

As if on cue, Charlie pressed down on his stomach with his hands.

“He was so thin that from the side he resembled a wooden plank,” Mikizo Fukazawa, the news correspondent, said. “The thighs were no thicker than the arms of a child.”

The doctor asked Charlie if he knew that Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Japanese.

“I know,” Charlie said.

“You know the American aircraft carrier Saratoga was sunk in the Battle of Coral Sea?” the doctor asked, trying to mislead Charlie with misinformation.

“No, I didn’t know that.”

“The Japanese army has already taken the Aleutian Islands,” the doctor said. “You still think the Americans can win the war?”

Charlie remained silent.

The doctor changed his line of questioning and asked Charlie about his background in the navy and his family. Charlie’s friendly expression turned serious.

“When you return to Tokyo,” said Charlie to Mikizo Fukazawa, “please send my wife and daughter a telegram saying that I’m safe and under the protection of the Japanese army, so they won’t worry.”

Charlie carefully spelled out the names and address of his wife and daughter in California.

The Japanese newspaper reporter was incredulous. He couldn’t believe Charlie’s request.

“I felt sorry for him,” Fukazawa said. “But deep in my heart I was thinking about something else. What if he had been a Japanese soldier? It would be unthinkable for a healthy Japanese soldier to allow himself to be taken prisoner. Even if he had been injured and consequently captured, not only would no Japanese act so friendly toward his captors, it would not even occur to him to plead for a message to be delivered to his family stating that he was alive and well. As I listened to this man, I learned a lesson in the differences between Japanese and Americans.”

The telegram was never sent.

For the next three weeks, the Japanese gave Charlie all the food he could eat, so he would gain weight. Once he regained his strength, they put him to work. He spent his days with other Japanese workers, filling sandbags.

But that came to an end on September 20, 1942. Two months after Charlie surrendered, he was put on a cargo ship departing for Japan. When he was told to go into the hatch where they kept the coal, he was greeted by Chief Mike Hodikoff and the Attuans, who were also onboard.

Their fate would remain a mystery until after the war.