SEPTEMBER 14, 1942. KISKA, ALASKA.

Six days before Charlie was loaded onto a cargo ship heading for Japan, he heard a loud droning noise while he was filling sandbags with the other Japanese workers on the beach in Kiska. Looking up into the sky, he saw fourteen P-39 Airacobra fighter planes dive down and continue flying dangerously low over the harbor. The Americans were on their way to drop more bombs on Kiska.

The P-39 Airacobra fighter planes came in first, attacking the Japanese antiaircraft defenses while the P-38 Lightning fighter planes attacked the Japanese Zero fighter seaplanes (Allied codename Rufes), which were sitting ducks, bobbing up and down in the water.

Behind these fighters were twelve B-24 Liberators and one B-17 Flying Fortress. Once the fighter planes weakened the Japanese’s defenses, the bombers headed toward the main camp with their machine guns firing.

Kiska bombing

The American pilots planned on taking the Japanese by surprise, flying in low so the Japanese radar couldn’t detect them. Unfortunately, the day was so clear that the Japanese could see them coming.

The fourteen P-38 Lightnings opened fire on the camp with their machine guns. Bullets were flying everywhere. Twelve B-24 Liberators followed closely, flying as low as fifty feet, unloading their bombs on the area below.

A Japanese officer had told Charlie he was supposed to always go into the powerhouse for shelter. Instead, he ran for cover into a narrow underground tunnel. He was too tall to stand up, but he didn’t care.

“I was reluctant to run through that mess of gunfire and dropping bombs,” Charlie said.

The bombs shook the earth, kicking up the claylike mud. Ten buildings caught on fire and burned black smoke. One bomb fell through the roof of the weather team’s powerhouse. It landed squarely on Charlie’s blankets and blew out a wall.

Belatedly, the Japanese pilots fired up the five Rufes that weren’t destroyed in the attack and took to the air, dogfighting with the Airacobras. Two P-38 Lightnings went after the same Rufe and collided. The American fighters burst into flames on impact, killing everyone onboard. In the end, the fourteen Airacobras outnumbered the Rufes, and every Japanese plane went down in flames.

By the time the air raid was over, two Japanese ships had been sunk, three ships were on fire, three midget submarines were destroyed, and four hundred Japanese were dead or wounded.

This was the first major air attack from the new top secret air base in the Andreandof Islands in the Aleutians — Adak to be precise, just 240 miles away. Now a round-trip flight, including time to find the target and drop bombs, was less than three hours.

The intensity of the war increased as the bombing raids on Kiska became more frequent and effective. On October 14, four weeks later, the heaviest coordinated raid was made on Kiska. On the mission were six B-26 Marauders, nine B-24 Liberators, twelve P-38 Lightnings, and one B-17 Flying Fortress. As the P-38 Lightnings protected the B-24s from antiaircraft fire, the B-24s flew in low and dropped fire bombs on the main Japanese camp and 500-pound bombs on the submarine base.

Ten minutes later, the B-26 Marauders flew one hundred feet off the water into Gertrude Cove and dropped torpedoes, trying to hit a freighter but missing. One torpedo ran up onto the beach and exploded, while another one got stuck in the mud at the bottom of the cove.

After the last American bomber and fighter planes headed home, a lone B-17 bomber stayed behind, circling Kiska. Looking out over the left wing of the plane, the six-man crew — the pilot, copilot, bombardier-navigator, top turret gunner, tail gunner, and a radioman — could see the orange flames and black billowing smoke in the burning camp.

Sitting in the pilot’s seat, clad in a leather jacket with his wife’s silk stocking wrapped discreetly around his neck for good luck, was the mustached Colonel William O. Eareckson, Eric to his bomber friends, Wild Bill to his navy friends, and Colonel E to the lower-ranking men. He was the head of the Eleventh Air Force Bomber Command and the mastermind behind the low-level attacks on Kiska.

Since the fog in the Aleutians made it difficult to locate targets and drop bombs from the usual five thousand feet, Eric figured out a way to solve this problem. He trained his pilots to fly in low over the water at thirty to forty feet. This broke the cardinal rule of aviation that a pilot should always maintain a high altitude to avoid crashing into ground obstacles and provide a safety net in case the plane has technical problems.

At such a low level, the pilot, who was also in charge of pushing the button to drop the bomb, had to gauge it just right so the bomb would skip across the water like a stone, hitting ships and seaplanes. Eric also developed a four-and-a-half second delay fuse for the bombs so the pilot had enough time to pull up and get away before it blew up.

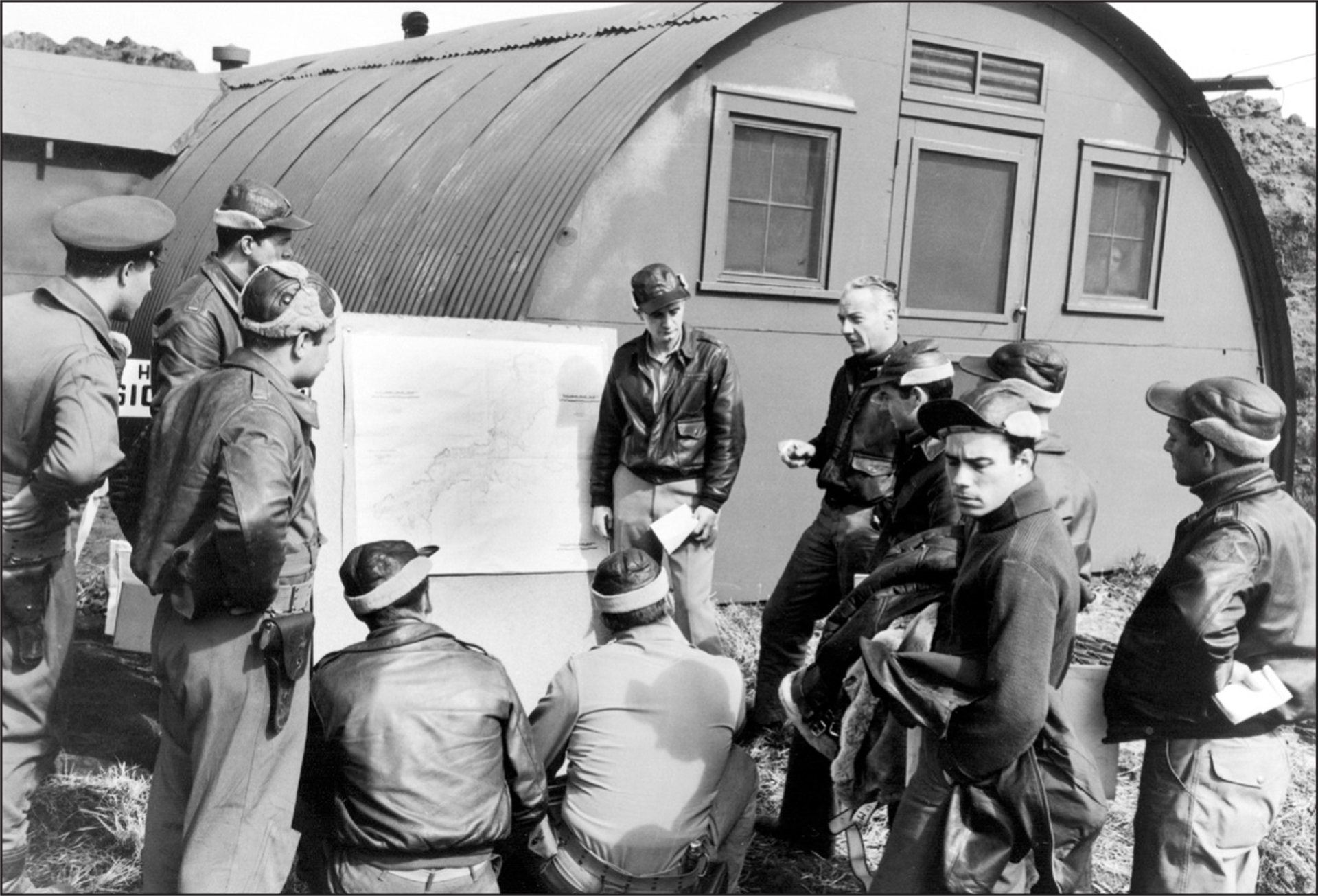

Colonel Eric Eareckson instructing his bomber pilots

However, flying in low made the planes easy targets for antiaircraft fire. So the fighter planes, which were equipped with .50 caliber machine guns that could rip through the armor plates of a destroyer, went in first and obliterated the antiaircraft fire coming from the destroyers and the weapons on land. This helped protect the heavy bombers from being shot down as they flew in afterward and dropped their big bombs.

In the air, there was no denying that Eric was the top dog, more than capable of flying all types of planes and working in any position on the crew. He went on nearly every mission because, as always, he never asked anyone to do something that he wouldn’t do himself.

“I wanted to show the kids it was all right; that if I could do it, they could,” said Eric.

He also liked to photograph the damage and, if the opportunity presented itself — which it always did when Eric was in the pilot’s seat — unload some bombs.

After snapping several photos, Eric circled around, looking for his target, the Japanese shore installations, while weaving in and out of the clouds to avoid the antiaircraft guns, all of which were pointed directly at him. A large hole in the clouds gave him the opportunity he needed to dive-bomb the target.

Peering through the bombsight control, he dropped through the hole and ignored the ack-ack-ack of machine guns firing away. A bullet tore into the left wing, and the plane suddenly jerked upward. Eric expertly righted the plane.

But more bullets ripped through the plane, tearing a hole in the gas tank. In the hailstorm of bullets, Eric suddenly lifted himself out of his seat and reached down to pick up a bullet. It was from a Japanese machine gun.

“Why the nerve of those so-and-sos. They’re shooting at me now!” said Eric, keeping his eyes focused on the target and his finger on the bomb release button. After unloading the last bomb, Eric was finally satisfied and he headed back to Adak. The first low-level bombing attack on Kiska was a success.

Colonel Eareckson writing a message to the Japanese on a bomb he’s going to drop

On August 28, 1942, two and half weeks before the first air raid on Kiska from Adak, in the middle of the night, two submarines surfaced near the shore of Adak. Quickly and quietly, two dozen men climbed onto five rubber rafts and paddled against the Aleutian wind. It was four miles to the shore.

At first glance, it was obvious they weren’t typical soldiers. In fact, they didn’t look like soldiers at all. They didn’t wear uniforms, or insignia, and some preferred to wear buckskin jackets.

Leading this pack of unusual-looking soldiers was a man with a bald head and a scar on his face. His name was Colonel Lawrence Castner, and he was in charge of what was officially called the Alaska Combat Intelligence Platoon, also known as the Alaska Scouts. Everyone called them Castner’s Cutthroats.

A soldier couldn’t apply to become one of Castner’s Cutthroats; Castner came for you. He handpicked each one. They were a mix of hunters, fishermen, prospectors, and trappers, and some were Eskimos, American Indians, and Aleuts. What they all had in common was their ability to live off the land and survive in the Alaskan wilderness all alone, and none of them liked to follow the rules.

Their main job was to spy on the Japanese and gather intelligence without being detected or leaving a trace of their existence — a Cutthroat was so stealthy that he could crawl through tall grass while barely moving it. They also knew Morse code, surveying, and mapmaking, and their maps were crucial in helping the other troops determine where to safely land.

Castner’s right-hand man was the hard-bitten Major William Verbeck. Like all Cutthroats, he carried his own weapons of choice, and his knife was one of his prized possessions. He’d asked a surgeon to design the blade so when he stabbed someone the blade would go in and out with ease.

Major Verbeck, who also spoke Japanese, trained the Cutthroats to fight like commandos — hand-to-hand combat that included silent kills from a short distance.

Another of Colonel Castner’s most valuable cutthroats was Simeon Pletnikoff, nicknamed Aleut Pete. Colonel Castner chose Aleut Pete because he was born and raised in the Aleutians. He was a highly skilled trapper and hunter, plus he knew the land and ocean, which was vital for charting and mapmaking.

“Aleut Pete”

This war was very personal to him because Chief Hodikoff was his relative. His girlfriend also lived on Attu when the Japanese invaded. He didn’t know if either was dead or alive.

Tonight he and the others were potential targets for the Japanese as they skulked onto Adak to find out if the Japanese occupied it. General Buckner had big plans for Adak.

Logistically and strategically, the U.S. military needed an airstrip and base that was closer to the Japanese invaders. Currently, the closest airstrip was Fort Glenn on Umnak Island, six hundred miles from Kiska. An airstrip on Adak would allow the bomber and fighter pilots to make more air raids. Aleut Pete and the other Cutthroats were to map the island, looking for a place to build an airfield. And if they found any Japanese soldiers on Adak, their orders were to kill them on the spot.

As the Cutthroats scoured the island, some hiking forty-five miles, they looked for the enemy while it rained and the icy wind blew. No Japanese soldiers were found, and they discovered that the only flat area on Adak was the lagoon. In order to build an airstrip, the lagoon would have to be drained.

The Cutthroats signaled a PBY pilot flying overhead with a green cloth, a code for “all clear.” The word was out that the enemy was not on Adak. The Cutthroats’ mission was accomplished, and a new air base was quickly built.

Little did they know that when the Japanese discovered this new air base, it would be a pivotal point that would lead to an all-out war.

With the new air base in Adak, Eric and the other bomber pilots were now close enough to conduct continuous air raids. The goal was to get the Japanese out of the Aleutians as soon as possible.

An all-important weather station was set up on Adak, so the pilots knew when they could fly, and four more ten-man weather teams were set up in isolated outposts across the Aleutians. However, this time, some of Castner’s Cutthroats were assigned to support and protect them.

General Buckner also deployed some of his soldiers to Atka, St. Paul Island in the Pribilofs, as well as Seguam and Tanaga islands, part of the Andreanof Islands in the central Aleutians.

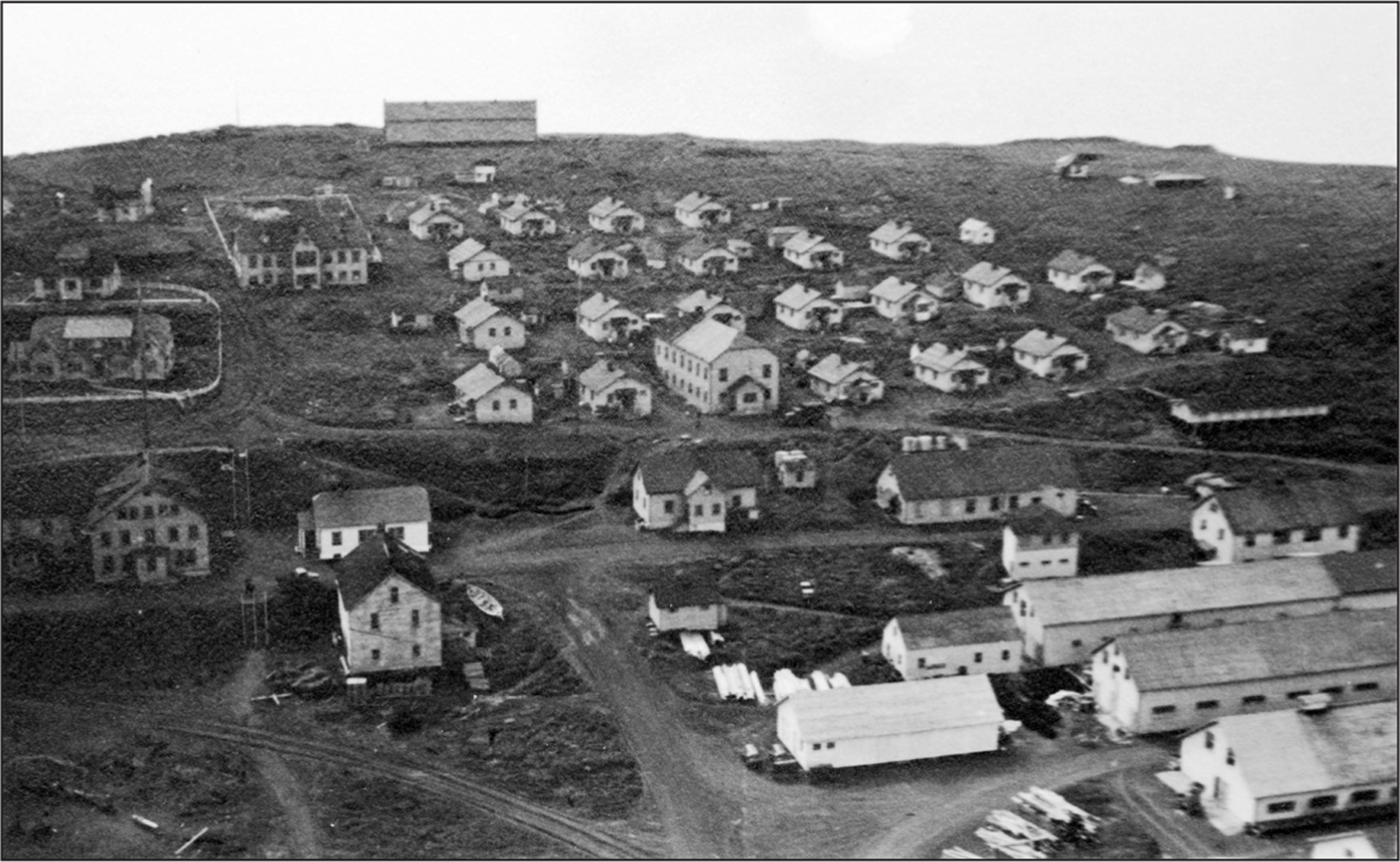

St. Paul Island

What the Americans didn’t know at the time was that the Japanese didn’t plan on staying in the Aleutians through the winter. In fact, the Japanese soldiers had left Attu and moved to Kiska, and the Japanese planned to move everyone to the Kurile Islands, fifteen hundred miles from Kiska, where the Japanese had a military base. But when a Japanese reconnaissance plane discovered the Americans had a new air base on Adak, and they learned American soldiers were in other parts of the Aleutians, the Japanese felt threatened. Now the Americans were not only closer to their troops on Kiska, but were in a position to launch an invasion of Japan. In this assumption, they were absolutely correct. From the strategically located Adak, General Buckner planned to oust the Japanese from the Aleutians and start a northern invasion of Japan.

As a result, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters abandoned their plan to leave the Aleutians in the winter. Their new plan was to occupy the Aleutians forever.

On October 29, 1942, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Hiroshi Yanekawa, Japan sent more troops to occupy Attu and to build an airfield. The U.S. military didn’t even know the Japanese were back until November 7, when one of Eric’s pilots flew over Attu and noticed the enemy — a week and a half after they had arrived.

Japanese officers on Attu

For the U.S. military, their next move was to set up another air base on Amchitka Island, just forty-five miles from Kiska, in January 1943. They also planned to starve the Japanese out of Attu and Kiska with a naval blockade. The last ship to bring food and supplies to the Japanese on Attu arrived on March 10. Against the odds, the Americans successfully blockaded the Japanese supply ships.

However, trying to starve them out didn’t work. The Japanese supplemented their supply of rice, sake, and tea by fishing and digging for clams.

The Japanese were steadfastly refusing to leave. Their orders were “to hold the western Aleutians at all costs.”

This left one last option for General Buckner. In order to oust the Japanese from the Aleutians, American soldiers would have to go to Attu and Kiska and fight them.

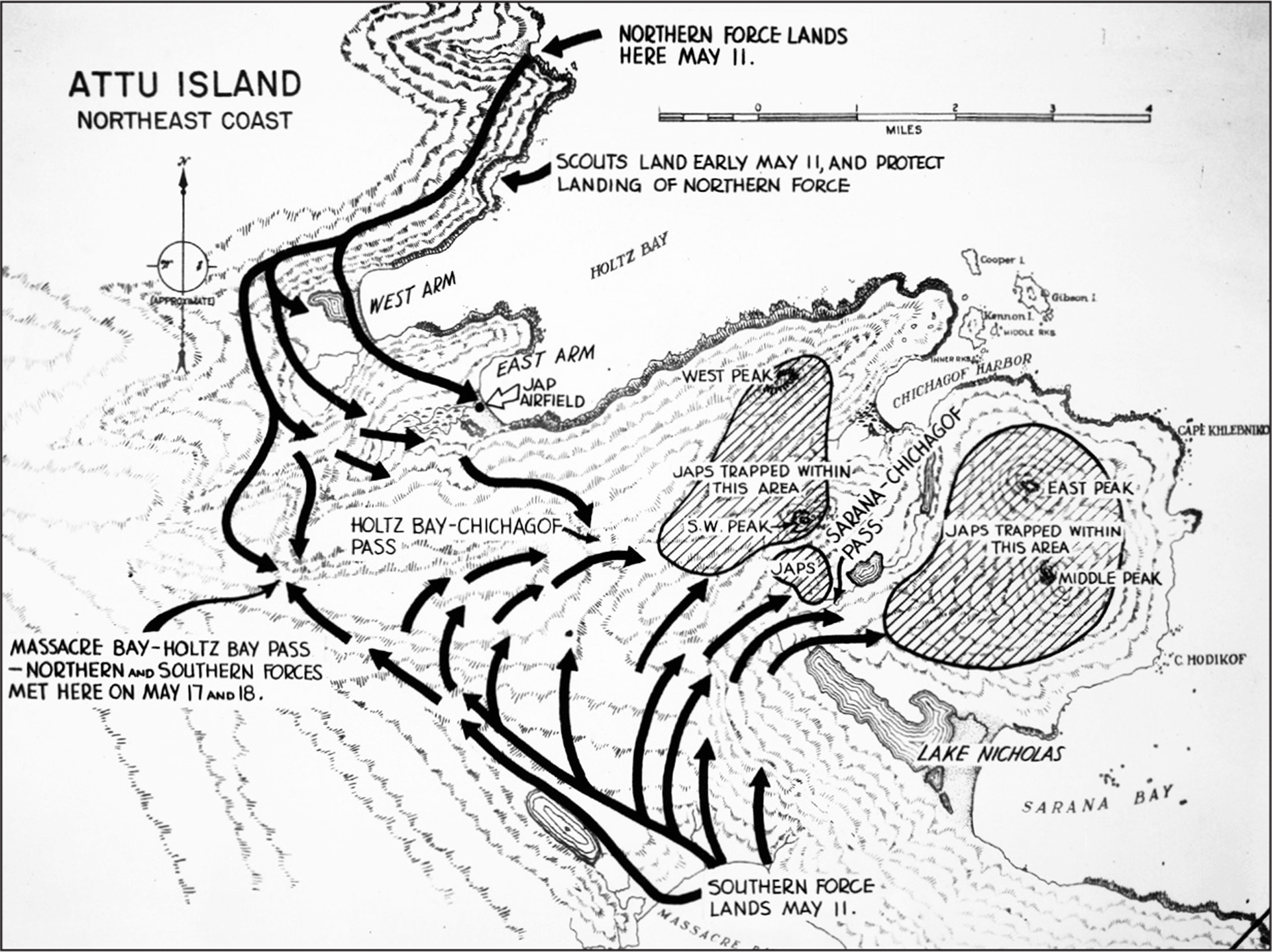

The plan, called Operation Landcrab, was to circumvent Kiska and take back Attu first. The American troops would surround the Japanese and squeeze them out. It would be an underwater assault coupled with air strikes led by Eric and his bomber pilots with reinforcements from the Royal Canadian Air Force. The War Department agreed to assign a special combat unit from California to increase the number of troops. Castner’s Cutthroats were going into combat, too.

U.S. strategy map for Attu

The Americans were confident that the battle would last three days — at most. What they hadn’t counted on was that the Japanese knew they were coming.

By the time the Americans realized that they had severely underestimated the Japanese soldiers’ strength, honor, and sheer determination, it was too late. They found themselves fighting in one of the bloodiest and deadliest hand-to-hand combat battles against Japan.