MAY 29, 1943. ATTU, ALASKA, AT THE TOP OF MASSACRE VALLEY DOWN THROUGH CHICHAGOF VALLEY.

The roar of the Caterpillar tractors could be heard throughout the night while the U.S. soldiers tried to sleep in their soggy and mud-caked sleeping bags. The noise from the engine and wheels had replaced the sounds of guns firing and grenades exploding amidst anguished cries of pain and loss. The sound of the tractors moving through the wet and spongy tundra signaled the end of the bloodbath, but it wasn’t much of a relief. It was only a merciless reminder of the nightmare.

Trailers were attached to the tractors to collect the corpses that were scattered for miles in the ankle-deep mud. The drivers maneuvered the large wheels so they didn’t accidentally push the dead bodies deeper into the mud.

The men who were collecting the dead bodies sometimes seemed calm and efficient as they carried out the grim task. Other times it was just too much for them to bear, and they vomited.

Thousands of dead bodies lay haphazardly across the killing field. Some had been killed by gunshot wounds, some by bayonets, and others by exploding grenades. The lifeless bodies were mangled or blown into pieces, often beyond recognition.

Wounded U.S. soldier on Attu

For once, the notoriously bad Aleutian weather was finally working in everyone’s favor. The temperature was a chilly forty degrees Fahrenheit, preserving the thousands of dead bodies. The men collecting the dead needed time for such a big job.

Some of the bodies were examined to determine the cause of death, and some of the pockets of the dead soldiers were searched for any personal belongings, which were then placed in a clean wool sock for safekeeping. They also looked for each dead soldier’s dog tags, which identified him by name. One tag was left around his neck, and the other was nailed to a grave marker. Finally, a set of fingerprints was taken. Each body was wrapped in a tan-colored blanket, ready for burial. There weren’t any caskets.

It would take days to bury all of the dead. Bulldozers were also busy digging mass graves where there wouldn’t be any grave markers. When every last dead soldier was finally buried, it would mark the end of a battle that shocked every person who lived through it.

It was about noon on May 11, 1943, when Aleut Pete and the other Castner’s Cutthroats silently rowed plastic dories through the dense fog toward Red Beach on Attu. The invasion to take back the island had officially begun. Technically, it was already supposed to be over, but they were late getting started. For the last four days, the fog and stormy weather had made it impossible to reach Attu safely.

Since General Buckner didn’t have enough combat forces of his own for the battle on Attu, the War Department assigned the Seventh Infantry Division. This specialized combat group of ten thousand men was brought in for the bloody job of blasting the Japanese soldiers out of their foxholes, trenches, and bunkers.

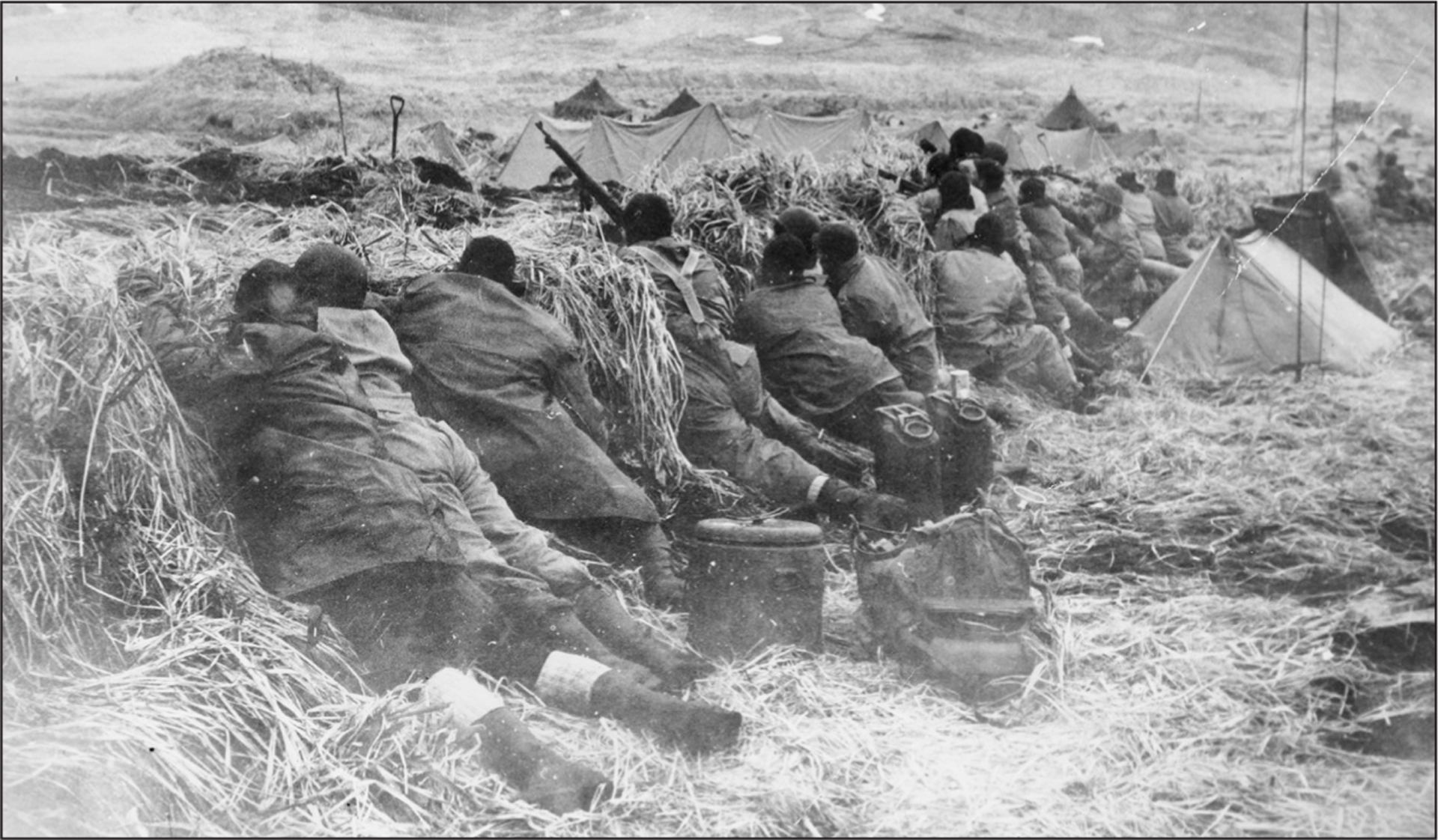

U.S. soldiers at Attu

The U.S. plan of attack involved dividing the Seventh Infantry into four groups: the Northern Force, the Southern Force, the Scout Battalion, and the Reserve Group, which would wait onboard a ship. The strategy was for the Northern, Southern, and Scout Battalion forces to close in on the Japanese from three different points. The idea was to push them toward Chichagof Valley (near the village of Attu) and trap them. The Northern and Southern Forces would meet midway and take on the Japanese together. The Scout Battalion was to make sure the Japanese didn’t retreat into the mountains where they could hide out and prolong the battle for months. There would also be a naval bombardment and air attacks from Eric and his pilots.

The only problem — and it was a big one — was that the Seventh Infantry was completely unprepared for the cold and rainy Aleutian climate. Their specialty was desert combat, and they arrived in the Aleutians wearing short-sleeve fatigues and leather boots, which offered no protection from the rain and snow. Nevertheless, the higher-ups didn’t think inadequate clothing was a concern because they believed the battle was only going to last for three days. This would be a costly and deadly miscalculation.

Another big problem was that no one had a reliable map. In fact, some areas on the map they did have were blank. This was why Aleut Pete and the other Cutthroats were sent ashore before the Seventh Division Northern Force, to check out the area. The six landing craft poised behind the Cutthroats were waiting to hear if it was even possible to land on Red Beach.

It was. The beach was narrow, making the landing tricky, but not impossible. A few hours later fifteen hundred men were onshore and, surprisingly, not a single shot was fired by the Japanese.

Earlier, in the predawn hours, Captain William Willoughby and his group of 244 men of the Scout Battalion successfully landed on Beach Scarlet in Austin Cove. Shivering in the chilly temperature, and with only enough food to last for a day and a half, they began their slog up the snowy and rugged mountains. No enemy was in sight.

The Southern Force landed on Massacre Bay (so named because in 1745 the Russian fur hunters murdered fifteen Attuans there) by mid afternoon in fog so thick that some of the boats ended up on the wrong beach. Like the Northern Force and Scout Battalion, once the troops landed on the treeless island, they immediately took cover in the rocky foothills, without a single shot being fired by the Japanese.

What the U.S. soldiers would soon discover was that the Japanese had a trap of their own. High up along the snowy mountainous ridges, the Japanese soldiers were waiting in big dry foxholes with plenty of guns, ammunition, and food. Some of the foxholes even had underground chambers that could hold a dozen men.

To top it off, the Japanese were well hidden by the fog and were further camouflaged in white fur-lined uniforms — coats, vests, mittens, and boots.

“The Japanese had dug in well,” said Eugene Burns, a New York Times newspaper reporter on the scene. “Their mountainside positions were prepared so that they offered the maximum protection and the best field of fire through which troops had to go.”

American soldiers in a trench, firing back at Japanese soldiers on a hillside hidden in the fog

On this day, the fog was the ally of the Japanese and an enemy to the U.S. soldiers. The Americans couldn’t see the Japanese, but the Japanese could see the Americans. They watched and waited in the fog with their guns pointed at the U.S. soldiers down below.

“The Japanese had dug tunnels for strong points that we couldn’t see through the fog,” said Sergeant William S. Jones. “They sniped at us every time the fog lifted. As soon as we concentrated our fire back where we thought they were firing from, they pulled back into the tunnels. They were also using smokeless powder, and that made it hard to see where they were firing from.”

As the American combat troops tried to move forward and upward, the Japanese pinned them down, stopping their advance. When an American finally caught a glimpse of the Japanese, the Japanese soldiers would disappear into the fog.

By the next day, forty-four American soldiers were dead. But that was only the beginning.

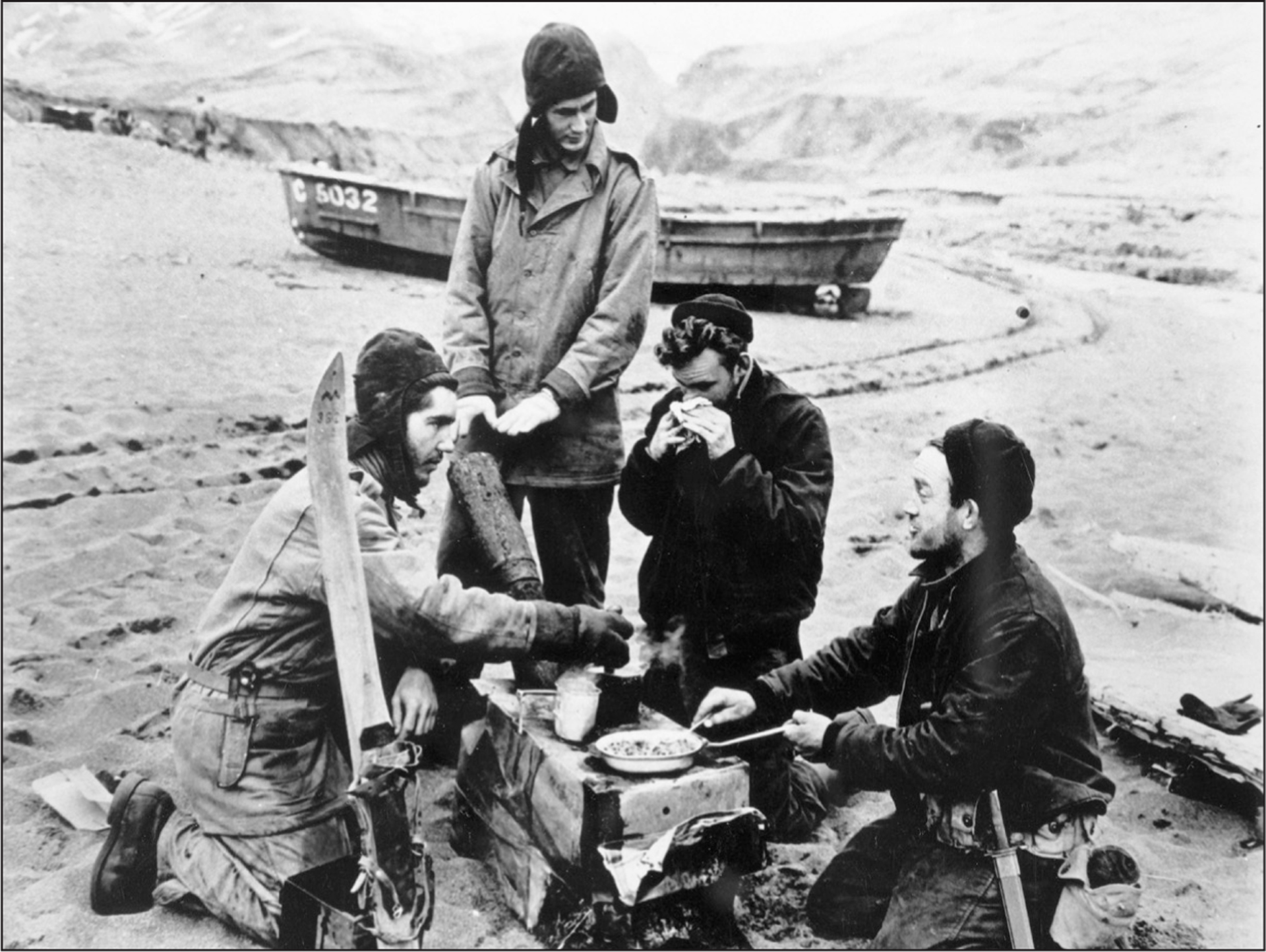

U.S. soldiers cooking on Attu

By May 14, 1943, on the fourth day of the battle for Attu, little progress had been made, and the U.S. soldiers were out of food and ravenous. On the first day, Lieutenant Anthony Brannen piloted a B-24 and tried to air-drop food and ammunition by parachutes to Captain Willoughby, but the wind blew the supplies into a crevasse and the troops couldn’t get to them. He tried again the following day, but crashed into a mountain and was killed. Since then, the planes were socked in by the fog and hadn’t been able to drop supplies. No one — with the exception of Eric — was daring enough to fly in it.

The American troops were vulnerable, but the fog was both an enemy and ally. At this point in time, if the Japanese had been able to launch an air attack from their military base on Paramushir Island in the Kuriles, the American troops would have been wiped out.

Of the 12,500 American soldiers on Attu, hundreds were suffering from frostbite and trench foot within the first few days.

U.S. soldier being treated for trench foot

When the temperature was less than fifty-five degrees Farenheit, as it was in the Aleutians, it only took a few hours for the soldiers’ wet feet to develop trench foot. This excruciating condition caused their feet to swell, damaging the nerves and muscles. Each step caused extreme pain, and some of the men were forced to crawl on their hands and knees.

When their feet were finally dry and warmed, the skin turned red or blue and blisters bubbled up. Some got infected, causing gangrene to set in, which destroyed the tissue and often resulted in their feet being amputated.

It wasn’t until May 16, 1943, six days after the U.S. troops landed, that they finally had a breakthrough. When the sun finally set around 10:30 P.M., Colonel Frank L. Culin and his Company B of the Seventh Infantry climbed the rugged ridge on Davis Hill and attacked the Japanese head-on.

U.S. soldiers waiting for a mortar shell to explode

For several bloody hours they fought in hand-to-hand combat, finally forcing the Japanese to retreat. The Americans now had control of Holtz Valley. Company B of the Seventh Infantry would be awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their fearless and valiant fighting.

For the next ten days, the fighting between the Americans and Japanese was brutal. Slowly, the Japanese were being pushed back toward the main Japanese camp in Chichagof Harbor. The U.S. plan was working, until May 26, 1943, when it came to a standstill.

For two days, on the snowy and rocky ridge called Fish Hook, Company K of the Thirty-Second Infantry had been trying to break through the Japanese line of defense. If the Americans succeeded, it would be the last push needed to send the Japanese into the final trap — but the Japanese weren’t giving an inch.

Whenever the Japanese were cornered, they fought harder. They were strategically positioned in a cliff above the American soldiers. From their trench in an overhang, they fired their guns and threw grenades, pinning down the American soldiers below.

Crouched behind a rock, with bullets whistling past his head, was twenty-three-year-old Private Joseph P. Martinez. Joe was a man of few words. Before joining the army ten months earlier, he had worked on a farm, growing and harvesting sugar beets in a small Colorado town. Now he was armed with a Browning automatic rifle (BAR) and had a bag of grenades hanging from his shoulder.

The situation seemed hopeless. The Japanese position was too strong. It didn’t look like the Americans would ever break through.

Suddenly, Joe stood up in the line of fire. He ran up the crest of the cliff through a hail of gunfire and positioned himself on a rock that protruded from the edge. He fired away at the Japanese soldiers, continuing to kill one soldier after another.

“And then we heard it,” said Sergeant Earl L. Marks. “A kind of crack and thoomp!”

Joe was hit. He fell backward, but no one could help him because the Japanese were pummeling them with grenades. After about half a dozen grenades were tossed, it was silent.

The fight was over for now, and by killing five Japanese soldiers, Joe had single-handedly cleared a section of Fish Hook, allowing the U.S. soldiers to finally advance.

From a distance, Earl could see Joe. He looked dead, but then his hand moved. Earl and Sergeant Glen Swearingen crawled over the cold ground toward him.

“He had been hit through the edge of his helmet,” said Earl.

Glen took off his jacket and placed it under Joe. Joe moaned in agony, but there weren’t any stretchers to move him to a field hospital.

That night the air was bitterly cold and snow was falling, but Company K armed themselves with a newly delivered stash of grenades and made their way up the crest to the pass where the Japanese were holding their defensive position.

“We let the grenades sizzle for about three counts and then tossed them over,” said Earl.

The exploding grenades lit up the pass, and the Japanese were quick to throw grenades back. A hushed silence suddenly fell, and the fighting ceased.

When morning came the Japanese were gone; they had retreated, and Joe was dead. He would receive the Medal of Honor posthumously, the highest honor awarded for heroism. Joe was the first private to earn the medal in World War II and the only one to earn it in the Battle of Attu.

Two days later, on May 28, 1943, the Japanese were surrounded by American soldiers who were now high up in the ridges looking down on them in Chichagof Valley. Eric and his bomber pilots had flown in and demolished the Japanese camp and the village of Attu. The Japanese had little food, ammunition, or supplies left, and no one was going to come to help them. The fleet of submarines that was sent to evacuate them couldn’t break through the U.S. naval blockade.

A PBY was sent to fly over the Japanese camp and drop thousands of leaflets with instructions for the Japanese to surrender. The Japanese were trapped, but their leader, Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki, had a plan — one that American military historians considered brilliant. It was the one tactic that could reverse the battle, turning the tide in Japan’s favor.

Colonel Yamasaki ordered all documents to be burned and called a meeting of his troops.

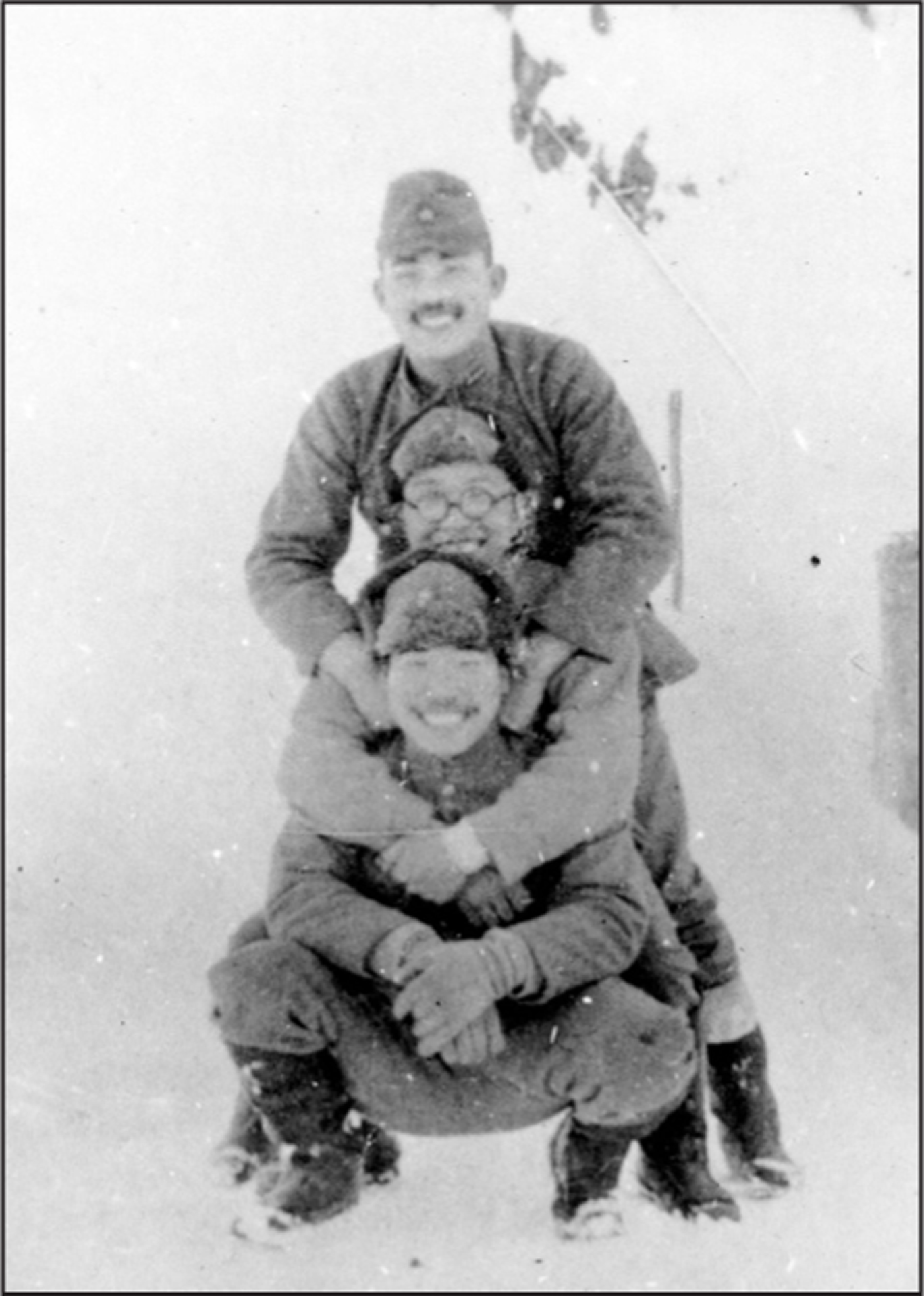

Japanese soldiers on Attu during the winter of 1943

“We are planning a successful annihilation of the enemy,” he told them.

At the meeting, listening to Colonel Yamasaki give his orders, was the quiet and studious Dr. Paul Nobuo Tatsuguchi. Paul was born and raised in Hiroshima, Japan, but had been educated in America, just like his father and his older brother. He studied at Pacific Union College and Loma Linda University School of Medicine in California, where he earned his medical degree in 1938.

Paul loved America. He was filled with good memories of traveling to Yosemite National Park, where he’d proposed to his wife, Taeko. He and Taeko planned on returning to America with their two young daughters after the war.

Paul was a devout Christian and had gone back to Japan after graduating to do missionary work for the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. In Japan, Paul worked at the Tokyo Sanitarium, which specialized in cases of tuberculosis.

Paul was drafted into the Japanese army, but he did not believe in war. It was against his Christian faith. However, he wanted to save lives, and he could do that as a doctor in the war. So when he received his orders from Colonel Yamasaki to “tend to” his wounded patients he felt sickened and at odds with himself.

As Paul made his way to the new field hospital through the deep muddy trenches, which snaked for two miles across the valley, he felt his stomach aching from hunger. Food had been so scarce for the past week that the Japanese had begun stealing it from one another.

Paul carried his medical bags into the field hospital. Inside his bags were his diary, a used copy of Gray’s Anatomy, and his Bible. Stuck between the pages of the Bible was a photo of his wife and three-year-old daughter, Misako. He hadn’t yet seen his baby daughter, Mutsuko.

Following Colonel Yamasaki’s orders, Paul “tended to” the wounded patients in the field hospital. He gave the helpless and incapacitated patients lethal shots of morphine and the lucid patients hand grenades. Today, Paul wasn’t trying to heal their wounds or save their lives. He’d been ordered to kill them.

Paul and the other Japanese doctors were saving the patients’ honor by helping them follow the bushido code. Killing the wounded patients prevented the shame of being captured by the Americans and becoming prisoners of war.

In his diary, which he began when the Americans first landed on Attu, Paul wrote his final thoughts:

“The last assault is to be carried out. All the patients in the hospital were made to commit suicide. Only 33 years of living and I am to die here. I have no regrets. Banzai to the Emperor. I am grateful I have kept the peace of my soul which Edict bestowed upon me. At 1800 took care of all the patients with grenades. Good-bye Taeko, my beloved wife, who has loved to the last. Until we meet again, grant you Godspeed.”

By three A.M., when it was still dark, Colonel Yamasaki and his soldiers armed themselves with the few guns and grenades they had, some of which had been captured from the American soldiers. Those who didn’t have a gun, attached a bayonet to a stick. Using up the last of their rice supply, each soldier was given two baseball-sized rice balls. If they needed more food, they were told to steal it from the pockets of their dead comrades.

Like ninja warriors, they moved silently through the darkness and shifting fog. The American soldiers standing guard at their camp in the middle of Chichagof Valley didn’t hear or see them coming. The Japanese plunged their bayonets into the American soldiers. They had broken through the American front line and quickly charged ahead, killing several sleeping men in a nearby foxhole.

With their guns loaded and bayonets drawn, they charged a camp of unsuspecting Americans who were asleep in their tents. It was a full-fledged banzai attack.

“We die — you die, too!” the Japanese screamed, over and over again.

The Japanese mission was to capture several artillery guns and turn them on the Americans. And, while the banzai attack created mayhem, the Japanese soldiers planned to raid the Americans’ supply of food and ammunition. But first, they needed to get to Engineer Hill, located at the north end of the eastern ridgeline of Massacre Valley. It was where the Americans had stashed the supplies for the infantry.

Approximately eight hundred Japanese soldiers swarmed into the base of Engineer Hill and surrounded the Americans. Captain Willoughby was attacked while trying to sleep in his foxhole. “I got a machine-gun bullet across my face and then a hand grenade came into the hole with me. It put some hunks of heavy metal in me, tore up my chest and arm.”

The attack raged on for several hours. In a hospital tent, the wounded Americans were piling up. Fighting could be heard in the distance as Captain Charles H. Yellin tried to save the wounded. Suddenly, machine-gun bullets ripped through the tent and bayonets tore it wide open. Outside, the screaming Japanese pulled the pins out of their grenades and threw them at the men inside. Captain Yellin survived.

“I was on the left flank when they came at us,” said Technician Fifth Grade Victor J. Unrein, who was shot near his kidney. “There must have been six or seven hundred of them in the attack.”

When the morning sun finally lit up the sky, it revealed the bloodshed. Everyone was either dead or wounded from bullets and shrapnel.

In the meantime, American soldiers fled the scene, racing up Engineer Hill to alert the others. Having no time to put on their shoes, some ran through the icy cold and snow barefooted.

There weren’t any combat soldiers on Engineer Hill; they were all engineers and bulldozer drivers as well as cooks, supply haulers, and staff officers. But they grabbed their weapons and got ready to fire. They managed to fend off the Japanese until the infantry advanced and pinned the Japanese down.

The banzai attack was over by mid afternoon, but not the killing. By nightfall, Colonel Yamasaki was dead, and the five hundred remaining Japanese soldiers honored the bushido code: Death before dishonor.

“All of a sudden, you could see the Japanese jump and fall down,” said Thomas A. Quintrell, an army officer. “It was their grenades — they were killing themselves.”

Ordered to kill themselves instead of surrendering, the Japanese pulled the pins of their grenades, armed them with a tap to their helmet, and held them to their head, chest, or stomach.

Mass suicide of the Japanese soldiers on Attu

Lying dead near a field-hospital tent was Dr. Paul Tatsuguchi. It was unclear how he met his fate, but it is believed that he tried to surrender. However, the U.S. soldiers did not hear him, and they shot him.

Lying near Paul’s lifeless body were his medical bags. An American soldier found them and brought them to Dr. J. Lawrence Whitaker, a battalion surgeon in the Thirty-Second Infantry, Seventh Division, who was working in the nearby hospital station. When Lawrence looked through the medical bags, he found Paul’s secondhand Gray’s Anatomy. When he opened it and looked at the inside cover he was shocked to see the names Ed Lee and Paul Tatsuguchi.

Later, his shock turned to sadness when Paul’s diary was found and a startling truth was revealed. Ed Lee had been a classmate of Paul’s and Lawrence’s in medical school. Lawrence had bought this copy of Gray’s Anatomy from Ed Lee and, in his senior year, had sold it to Paul, who was a junior at the time. Lawrence and Paul actually knew each other from school.

The fight for Attu was a costly war in human lives. It was one of the biggest mass suicides in World War II. For every ten Japanese soldiers who were killed, seven American soldiers were killed or wounded. There were more than 15,000 U.S. soldiers on Attu, and of those, 549 were killed in action, 1,148 were wounded, and 1,200 had severe injuries from the cold. By the end, 2,650 Japanese soldiers and civilians were dead, leaving only 29 alive. The living Japanese were cooks, hospital orderlies, and civilian laborers who became prisoners of war. No Japanese officers survived.

Not expecting any of their men to be taken alive, the Japanese had not been told what to do if they were captured. As a result, the Japanese prisoners were very obedient to authority. Castner’s Cutthroat Major William Verbeck was a witness to the interrogation of the first Japanese prisoners captured on Attu.

“The Japanese prisoner … has never been told not to talk in event of capture,” he reported. “Because the possibility of capture is never considered by the enemy. As a result, this well-disciplined Japanese soldier obeys orders and answers any questions we direct to him.”

When questioned, the Japanese prisoners said they did not kill themselves because they were either lost or had no grenades. All of them said they didn’t want their families to know they were still alive.

“I’d like to go back to Japan,” said one Japanese POW. “But if I go back I’d be a disgrace to the folks so I don’t know what to do. Under such circumstances we are theoretically dead, so if there is anything I can do to work for the United States I’d like to do that.”

Japanese POWs

On May 31, 1943, the Japanese government issued a statement about the Battle of Attu: “It is assumed the entire Japanese force has preferred death to dishonor.”

The battle for Attu was over, and so were the lives of thousands of men.