SEPTEMBER 17, 1945. OTARU, HOKKAIDO, JAPAN, TWO WEEKS AFTER JAPAN SURRENDERED AND THREE YEARS AFTER THE ALEUTS WERE TAKEN FROM ATTU.

On the western coast of Hokkaido Island in Otaru, Japan, near the Shimizu-cho Meiji Shrine, where Japanese devotees worshipped and made offerings to their gods and spirits, there was a wooden house. The house had five rooms that, at one time many years ago, were used by a Shinto priest for an office and living space.

When American bomber pilots flew over this single-story house, they could clearly see the letters PW written on top of the roof. These letters alerted the pilots that prisoners of war lived inside the house.

Also inside this shabby house was a big box. And inside this big box were twenty little boxes neatly stacked, one on top of the other. This big box was placed near a trunk containing Russian Orthodox Church books.

It hadn’t been difficult fitting all of the little boxes into the one large box. The difficult part had been picking up the charred bone fragments of the dead and trying to fit them into the little boxes. Sometimes the boxes simply weren’t big enough for the bones to fit.

Along with the twenty boxes of bones, there were twenty urns of ashes packed inside three military caskets. Three years had passed since the Attuans were captured and brought to Japan, and only about half of them had survived.

One of the worst things for the surviving Attuans was that they were not allowed to bury their dead, so the Attuans held on to their loved ones’ remains —the bones that didn’t burn and the flesh that turned to ashes during the cremation process. “We kept all our boxes carefully because we wanted to take them home to be buried some day,” said Alex Prossoff.

From the beginning of their journey from Attu to Japan, death was almost certain for all of them. When the ship left Attu, it first stopped at Kiska to pick up prisoner of war Charlie House.

For the two-week voyage to Japan, the Attuans remained in the foul-smelling and uncomfortable hold, without the benefit of fresh air or fresh food. Sickness was rampant.

Charlie helped care for the ailing children, and they called him Doc. However, after the ship finally arrived in Japan, they never saw Charlie again.

Since Charlie was in the U.S. Navy, the Japanese treated him as an enemy, and, as such, they believed they had the right to kill him any time they deemed necessary. When Charlie arrived at a secret naval base near Tokyo, they blindfolded him and told him that if he could see, they would have to shoot him.

From there, they took Charlie to a prison camp near Yokohama called Ofuna, which was dubbed a “torture farm” because beatings were an everyday occurrence for the prisoners. POWs in Japan were not protected by the Geneva conventions.

In 1929, political leaders from forty nations met and signed the Geneva convention, an international law that specifies the humane treatment of prisoners of war. Japan was present at the meeting and signed the agreement. Although Japan had signed this agreement, the Japanese government never ratified it because the military leaders opposed it. They believed it did not apply to them because their soldiers followed the bushido code, and would kill themselves to avoid becoming prisoners of war.

As a result, the Japanese disdained anyone who surrendered because, to them, it was a shameful act. So without the protection of the Geneva conventions, POWs in Japanese prison camps were tortured, beaten, starved, denied medical attention, deprived of aid from the Red Cross, and used as slave laborers.

Civilians like the Aleuts, on the other hand, were treated somewhat differently. The Japanese did not call them prisoners. Instead, civilians who were captured by the Japanese were referred to as detainees. As detainees, the Aleuts lived together as a family among the Japanese people instead of being sent to a prison camp. Nevertheless, there were guards who policed their every move, and it wasn’t long before they were starving.

When the Aleuts arrived in Japan in September 1942, the country’s economy was already feeling the squeeze from the cost of war. There was a shortage of coal, raw materials, and labor.

“When we were there, I used to think Japan must be one of the poorest countries in the whole world,” said Alex Prossoff. “In that town of Otaru … not one painted house did I see. One house only had a coat of tar. Everyone worked, and worked every day. Young boys and girls worked in the factories near the house where we lived.”

Earlier that year, a severe drought had destroyed many of Japan’s crops, causing a food shortage and inflated food prices. Sugar, meat, and bread were considered luxury items. And rice, their staple food, had to be rationed.

“At first we did all right because we ate the flour and sugar and fish we brought from Attu,” said Alex. “The Jap[anese] gave us only two cups of rice for about ten people a day. When our food was gone we could not buy any more from [the] Jap[anese]. Then we began to get very hungry.”

On the first night in Japan, Mike Lokanin’s baby daughter, Titiana, was crying for a bottle of milk. Titiana was still too young to eat solid foods. When Mike asked the Japanese guards for milk, they couldn’t understand one another. Eventually, Mike realized that there was no milk to give her.

The Aleuts soon learned that they had to adapt to many aspects of the Japanese culture. They were told to take off their shoes before entering their house. At first, they didn’t understand why because the house was dirty, but they learned this was a Japanese custom.

When they ate their first meal in Japan, instead of sitting in a chair at a table, the guard instructed them to sit on the floor cross-legged. Eating became problematic for the Aleuts when they were given chopsticks. Like many Americans at the time, the Aleuts didn’t know how to use chopsticks because they were accustomed to knives, forks, and spoons. So, as soon as the guards looked away or were busy talking to one another, the Aleuts shoveled their food into their mouths with their hands.

To sleep, they were given futons and tatami mats instead of the Western-style beds they were used to. “Pillows were also given to us, and they were very hard, but we did not complain,” said Olean Golodoff, the mother of seven children, all of whom were prisoners in Japan.

All of the Aleuts, including the children, were expected to learn how to speak Japanese.

“The Jap[anese] said they would kill us if we didn’t,” said Alex.

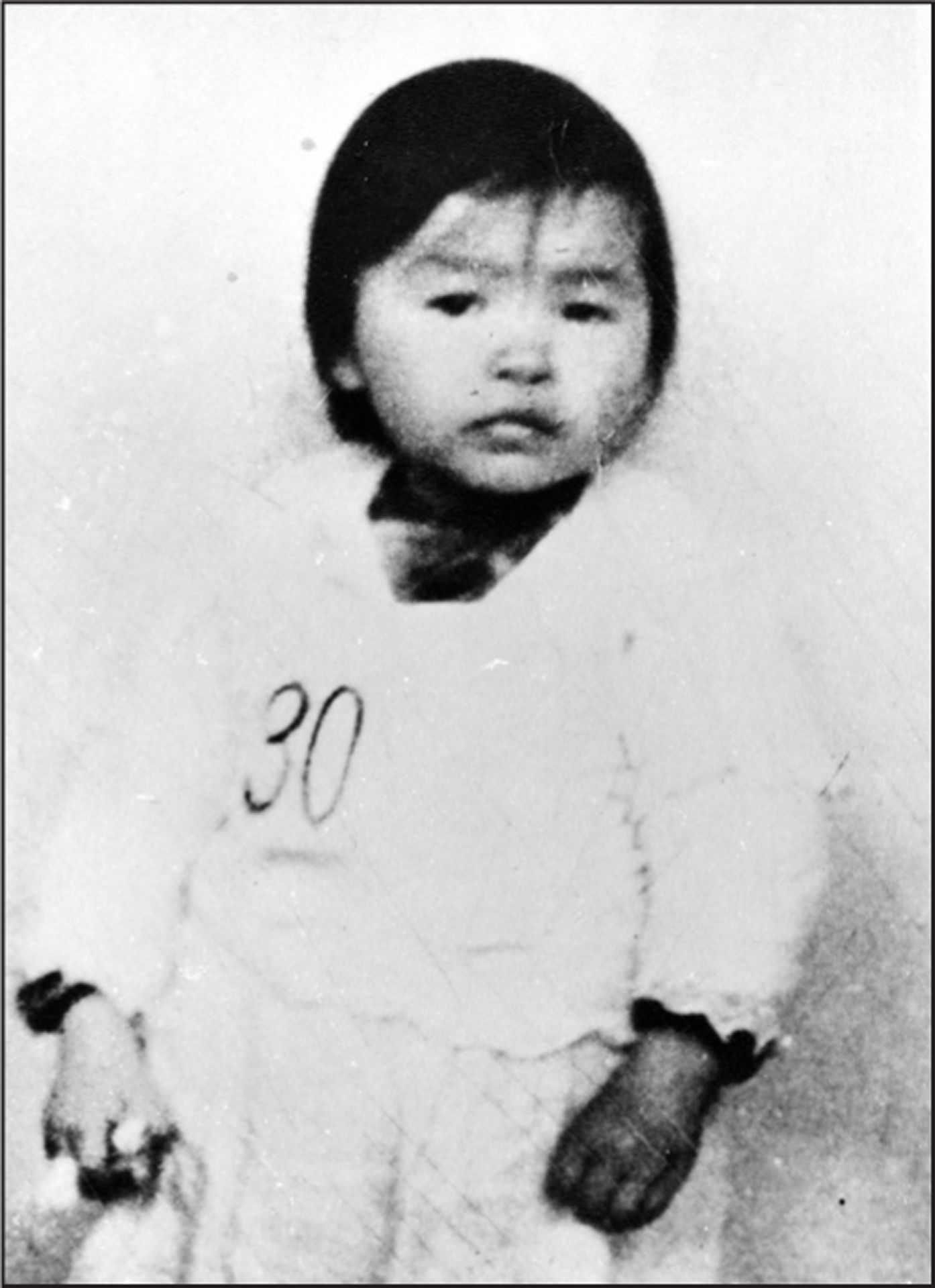

Elizabeth Golodoff Kudrin at 18 months old. She was taken to Japan in 1942 and didn’t return to the United States until age 3.

Like the American soldiers who were prisoners of war, the Attuans were beaten by the Japanese guards.

“Sometimes we were beaten and our women whipped,” said Alex.

“The less I remember the better,” said John Golodoff, who was Olean’s son and fifteen years old when he was taken to Japan. John was beaten for not working fast enough.

Angelina Hodikoff, who was Chief Mike Hodikoff’s sixteen-year-old daughter, had scars from the beatings she received. One time a Japanese guard threw a stone at her, wounding her, because she had stopped working.

Within the first month of arriving, the Aleuts were put to work in a mine digging bentonite, a type of white clay that had many different uses, out of the side of a mountain. The clay was then mashed with sticks so it could dry in the sun. When it finally turned into a powder, they turned on a machine with a fan that blew the powder through a pipe into a large hole in the ground.

Mike’s job was to keep the powder from plugging up the pipe. There was a large piece of canvas over the hole, and Mike was kept inside the hole until it filled up with powder. When the hole got full, he tapped on the canvas, and they would let him out. His nose, ears, mouth, and eyes would become caked with clay. The clumps of clay that collected in his throat made it difficult for him to breathe. However, Mike was allowed to drink water to help flush it out.

All of the Attuans’ medical records were destroyed after the war and before the American soldiers occupied Japan. However, years later, Dr. Fujino, who was the Attuans’ doctor, reported that there were always ten to fifteen Attuans in intensive care at any time. In 1943, the Attuans’ first year in Japan, just about everyone got sick and was taken to the hospital. They suffered from many diseases and illnesses, including tuberculosis, diphtheria, polio, beriberi, and blood poisoning.

In 1944, their second year in Japan, “Every one of us began to starve,” said Mike Lokanin. He watched helplessly as his daughter, Titiana, slowly died from starvation. The very next day, his newborn son, Gabriel, starved to death. Three days later, his wife, Parascovia, was hospitalized. “It was the hardest time we had,” said Mike.

Desperate for food in the winter of 1944, the Attuan men began to hunt through the trash looking for it. Even if it was just fish heads, guts, or potato peelings, they would take it. It was what they had to do to stay alive.

“We got so hungry we would dig in the hog boxes when the guards were not looking,” said Alex Prossoff. “Whatever we found we would wash it and cook it and try to eat it.”

A year later, in January 1945, Chief Mike Hodikoff and his son, George, died from food poisoning after eating from the garbage. The Japanese never gave the Attuans the packages of food, clothing, and medicine that were sent by the Red Cross during the war.

“Many Attu people died in Japan,” said Innokenty Golodoff. “Only twenty-five people came back.”

But they didn’t return to Attu. The village that they knew no longer existed. Like their boxes of bones and ashes, Attu was a casualty of war.

On the night of March 9, 1945, the United States began firebombing the cities of Japan, starting with Tokyo. Using napalm, a powder that is mixed with gasoline to create a jellylike explosive, hundreds of B-29 Superfortress planes began dropping bombs. The strategy was to attack industrial targets, factories, and railroad yards and burn down the surrounding cities.

The person in charge of the U.S. firebombing was the cigar-chomping General Curtis LeMay. He switched to the new tactic of firebombing because the high-altitude precision-bombing attacks had been ineffective in ending the war. The main obstacle had been the weather. The overcast skies and strong winds had made it difficult for the bomber pilots to hit the industrial targets.

After six firebombing raids, fifty-one square miles of Tokyo had burned to ashes, and the glow from the fire could be seen a hundred and fifty miles away. An estimated one hundred thousand Japanese died a horrific death.

When a firebomb explodes, the flaming jellylike substance from the bomb clings to and burns anything it hits. The smell of burning bodies was so intense that the bomber pilots wore oxygen masks to keep from vomiting. The massive fire also sucked the oxygen out of the air, boiled the water in the canals, and melted glass into liquid, which rolled down the streets.

The Americans relentlessly firebombed sixty-seven Japanese cities, hoping it would force the Japanese to surrender, but they refused.

On July 26, 1945, three years after Charlie and the Kiska weather team had been taken prisoners of war and three months after Benito Mussolini was executed and Hitler committed suicide, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding that Japan surrender unconditionally or face complete destruction. On July 28, 1945, Japan refused. The Japanese were prepared to defend their country with one million soldiers, three thousand kamikazes, five thousand suicide boats named Shinyos that were loaded with explosives and ready to crash into American ships, and millions of civilians ready and willing to fight to the death.

Nine days later, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. An estimated 140,000 people were killed, and the bomb completely devastated five square miles of the city.

Japan still refused to surrender. Two days later, on August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. The next day the United States dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

Mushroom cloud from after the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki

Japan surrendered unconditionally on August 15, 1945, marking V-J Day, the Allied victory over Japan, and bringing an end to World War II.

“I don’t think I could have survived another winter as a prisoner of war in Japan,” said Charlie House. “The atomic bomb saved my life, and that of the 146,000 other Allied POWs in Japan — 108,000 British and Imperial, 23,000 Dutch, and 15,000 Americans. If there had been an invasion, the Jap[anese] would have killed every one of us.”

On September 2, 1945, Japan signed the surrender document, and a half an hour later there were forty-two U.S. ships and thirteen thousand troops in Tokyo Bay. The Japanese agreed to release all of the prisoners of war and accepted the authority of the U.S. supreme commander, General Douglas MacArthur. Emperor Hirohito was permitted to be the symbolic head of state, but he was no longer worshipped by the Japanese people.

U.S. naval officers with Japanese officials at the surrender ceremony

It wasn’t until the war was over that the fate of Etta Jones, the schoolteacher from Attu, was revealed. All during the war, her family tried to find out if she was alive through the Red Cross, but they never received any information.

Her family found out that Etta was, in fact, still alive, but she only weighed eighty pounds. Like all prisoners of war, she suffered from starvation. Etta had been detained with eighteen Australian nurses, and they stayed alive by stealing leftover food from the guards’ plates. During their second-to-last month as prisoners, they ate almost nothing but boiled carrot greens. However, during the last two weeks the food improved when the Allied pilots dropped food parachutes.

“The Jap[anese] were really very nice to me,” said Etta. “They called me the ‘Oba San,’ which means the ‘aged one,’ and is considered a title of great respect.”

At sixty-five, gray-haired Etta was the oldest prisoner in the group, and the Japanese showed her more respect than they did to the younger nurses who were slapped and knocked down during their imprisonment. Some of the Australian nurses became sick with the flu, pneumonia, and beriberi. But they all survived.

All of the men from the Kiska weather team also survived their years at the Japanese prison camps. Explosion the dog survived, too.

By September 5, 1945, stories of the atrocities and brutal conditions the prisoners of war endured in Japan were published in newspapers all over the world. On that same day, the War Department issued a document directing prisoners of war not to discuss their experiences while interred or reveal any military intelligence. Walter Winfrey and other prisoners signed the document, promising to keep the information secret. They and many other POWs didn’t want to talk about their experiences because it was too painful. They wanted nothing more than to forget about what had happened to them.

Document issued by the U.S. government for POWs to sign, directing them not discuss their experiences

World War II was over, and with it the Aleutian War. Years later, it would be referred to as the Forgotten War because many Americans forgot or never knew that the Japanese invaded Alaska. It would be decades before these unforgettable stories were told.

Walter Winfrey one year after his return from Japan as a POW