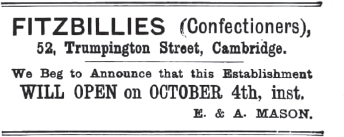

An advertisement in the Cambridge News tells us that Fitzbillies first opened its doors to customers on Monday, 4 October 1920. The date was no coincidence – it was the first Monday of the university term. And then, just as now, the owners would have known that they needed to be ready for this busy time of year.

Ernest and Arthur Mason founded Fitzbillies, using their demob money from the First World War to set up a confectioner’s at 52 Trumpington Street – their initials are still visible in worn-out gold letters on the shopfront. They were the sons of local character ‘Ticker’ Mason, who had a baker’s shop further up Trumpington Street, at number 41. The nickname ‘Ticker’ came from his custom of wearing an unusually loud pocket watch.

A small businessman with entrepreneurial spirit and making mainly bread, it was perhaps Ticker who spotted the opportunity and encouraged his sons to open a confectioner’s – a complementary business specialising in fancy cakes and pastries.

The beginning

Ernest and Arthur had the shopfront designed in the unusual Belgian Art Nouveau style that remains today. Perhaps they had seen this style when they were in Flanders during the war. It certainly contributed to the ‘high-class’ look and appeal of the business. The bakery was through the back of the shop, taking up the whole of the yard in the middle of the block. It had a huge brick oven with a tall chimney that remained in use until the 1980s.

Ernest and his wife Phyllis lived above the business. ‘Phil’, as she was known, ran the shop and we are told that ‘she was the one they were all scared of ’. Ernest and Arthur’s sisters, Maud, May and Doll, helped in the shop from time to time.

Fitzbillies quickly became the cake shop of choice for the university and town. It produced the full selection of buns, pastries, savouries and fancy cakes you would have found in any high-street confectioner’s of the time. In the early days it was even more famous for the special Fitzbillies sponge cake than for the Chelsea buns.

Philomena Guillebaud, a long-time resident of Cambridge and regular customer of Fitzbillies throughout her life, reminisced:

‘I was born in Cambridge in 1926, in a don’s family. Before the Second World War, no don’s family tea table would have been complete without a Fitzbillies’ sponge cake, it was THE THING for which Fitzbillies was famous. Chelsea buns – and Bath buns – and what we called candlegrease buns – were on offer, but it was the cake that carried the flag. And it was very good, and it was often preceded at the tea table by cucumber sandwiches on brown bread with the crusts cut off. Apparently the cake was never made again after the Second World War, perhaps because of rationing.

‘Here is the recipe. I got it from my sister, who got it from our mother, who got it (as a very very special favour) from the lady who ran Fitzbillies at the time, whose name my sister thinks was Mrs Mason. My sister remembers her as a rather grim-visaged lady, but our mother, who was known to be a good cook, evidently charmed her out of the recipe, which was otherwise a secret.

‘Don’t ask me for any clarifications, what I have given below is the verbatim text and is all we know.

8 eggs

8oz sugar

7oz flour

1 tsp pounded tangerine peel

Separate eggs, beat yolks and sugar till creamy, fold in beaten egg whites.

Sprinkle tangerine and flour at the same time.

Line a greased tin with fine breadcrumbs.

Bake in a very low oven for about 1½ hours.’

We are often asked why Fitzbillies is called Fitzbillies. The short answer is that it is a diminutive of Fitzwilliam, named after The Fitzwilliam Museum just down the road – but the long answer is more entertaining.

We know that Ernest and Arthur Mason originally wanted to call the business Fitzwilliam’s or Fitzwilliam Bakery. So why didn’t they? One story is that The Fitzwilliam Museum refused them permission; another that there was already a Fitzwilliam Bakery in Ireland, so they were unable to trademark the name.

Why Fitzbillies? Newspaper articles from the time refer to the fact that undergraduates irreverently called The Fitzwilliam Museum the ‘Fitzbilly Gallery’. And the motto of the rowing crew of Fitzwilliam College, then called Fitzwilliam House and situated on Trumpington Street, was and to this day still is, rather stirringly, ‘For Fitzbilly Pride’.

More scandalously, the original Viscount Fitzwilliam of Merrion, the benefactor of the museum, had two illegitimate sons whom he called Fitz and Billie. The historian of The Fitzwilliam Museum suggested Fitzbillies was named after them.

There is also a glacier in Svarlbard in Norway called the Fitzbilly Glacier or Fitzbillybreen. For a while, we were hopeful that it had been discovered and named after the shop by a true bun lover. However, we have to concede that it was actually named after Fitzwilliam College by one of the Cambridge men on expeditions to Norway in the 1920s and 30s.

‘GOING DOWN’ FOR THE LAST TIME

By A Cambridge Woman

‘We feel suddenly we must pack into these last days everything that we have most enjoyed. We must picnic up the river beyond Grantchester, where the stream runs slow and you can bathe. We must tramp once more over the Gog and Magog hills and find the Roman road that still runs as straight as the legions planned it. We must defy authority and spend a June night in the college orchard in hammocks slung precariously from baby apple trees. We must eat slabs and slabs of “Fitzbilly”cake – surely the most luscious sponge cake in the world and known only to a Cambridge baker.’

The Daily Mail

Wednesday, 5 June, 1929

The Second World War & rationing

The Second World War was a particularly challenging time for the business. Bakers and confectioners, like other catering businesses, had to apply to the Ministry of Food for their quota of ingredients. The allocations were usually well calculated, but nevertheless a trade grew up where businesses bartered with each other to get what they needed.

One of the bakers who came to barter ingredients during the war was Wilfred Day. He had a bakery business in Willingham, just outside Cambridge. He brought his son Garth with him, who was then in his teens. Garth told his father that when he was older he wanted to run Fitzbillies. Mr Day mentioned to the Masons that if they ever wanted to sell, he would like to have first refusal.

Although ingredients were in short supply during and after the war, demand for Chelsea buns was higher than ever. Customers now in their 90s have told us stories of their experiences as undergraduates in the late 1940s and early ‘50s. The food in colleges was terrible and meagre. A Chelsea bun was a huge luxury and the Masons must have wanted to make sure that the few buns available went to regular customers. So, the only way to get a Chelsea bun was to bring back the bag from your previous bun. It was a lucky undergraduate indeed who, on going to his new rooms at the beginning of term in October, found that the previous inhabitant had left him his Fitzbillies bag.

‘When the war was over, everyone thought food queues would be over, too. In fact, everything continued as greyly as before, and the most anxious queues I had ever joined were outside Fitzbillies in Cambridge. No undergraduate tea party was complete without their Chelsea Buns, syrupy, well spiced, licentious and exceptional during the years of ersatz cakes and shortages. I still think they are the best Chelsea Buns I have ever eaten.’

The Observer Guide to British Cookery by Jane Grigson

The next owners

Meanwhile, Garth Day grew up, joined the army and fought in Sicily. When he was demobbed in 1946 he went to the National Bakery School at Borough Polytechnic Institute, winning the Renshaw Cup for Confectionery. After leaving college he married Annette and they went into business in Aldeburgh. Then one day in 1958 he got a phone call from his father. The Masons had remembered his request and called to say they wanted to sell Fitzbillies.

Garth and Annette dropped everything and moved to Cambridge, bringing with them two long-serving members of staff: Malcolm Grayling who worked in the bakery and Yvonne who worked in the shop. Mr Day ran the bakery and, as a particularly skilled cake decorator, did much of the decorating himself. Mrs Day ran the shop with a firm hand and installed a series of mirrors so she could check that customers were never left unattended and to maintain surveillance over the till.

Christopher Day, Garth and Annette’s son, remembers his childhood growing up in the rooms above the shop in 52 Trumpington Street:

‘We lived on the premises, downstairs in the kitchen under the shop; and bedrooms, bathroom and living rooms (i.e. posh bits used only on special days) on the first and second floors. Our play areas were the store (back rooms leading to a passage to Downing St) and the passage to the bakery.

‘There was (what seemed to a small boy) a massive chimney above the oven at the back. In our time it was a stone oven, heated at 5 or 6 every morning. The first things to get baked were those which needed the hottest temperatures, followed by those needing gradually lower temperatures. Most of the bakery work was done by early afternoon, so the ‘men’ (which it was mostly) went home.

‘My father fired the oven every day. Like a steel furnace, the stone would crack if it cooled too much, which would wreck the oven. There was a fuel tank for the burner for the oven, which was refilled by a hose from a tanker in Trumpington St. In retrospect it was rather surprising that the whole lot didn’t go up in flames before it actually did.

‘My father used to take the bakery staff on a one-day trip every year (equivalent of a works outing, I suppose) mostly to the seaside, although I remember at least one year they splashed out and flew abroad (Copenhagen?) for a couple of days. (I don’t think similar benefits extended to the shop staff.)The whole business shut down for two weeks every August for summer holidays.’

Christopher’s sister, Patricia Birtles (née Day) remembers being set to work as a child and ‘at the age of 12 being paid 12s 6d for 7.30am–2pm on a Maundy Thursday packing hot cross buns in bags of 6s and 12s’. There were queues outside the shop and round past what was then Heffers bookshop on the corner.

Fitzbillies’ reputation was such that there were often long queues. There is a story that during the Cold War, Pravda ran a feature under a picture of the long lines queuing for Chelsea buns outside Fitzbillies claiming that even the affluent Westerners were forced to queue for bread.

It is also said that Edmund Hillary ordered a crate of Chelsea buns as part of the rations for his ascent of Everest. It seems likely that the high fat and sugar content would have assured their survival at Base Camp, but we are still searching for hard evidence.

Tom Whitehead started work at Fitzbillies in 1962 and gave a detailed account of how the business worked in those days:

‘At the back of the bakery was the old-fashioned side flue oven. A giant thing like a bunsen burner the size of a cannon. It heated a huge hot water tank as well.

‘The production was scheduled for the oven. Mr Day started at 6am to get the doughs ready. Then the oven was switched off and cleaned. Then the first firing went in. Sausage rolls, pies, meat products, bread, Chelsea buns, all in particular layers. When that came out it went straight into the shop when it opened at 8.30 to be served hot.

‘The bakers worked eight hours a day, five days a week and five hours on Saturdays at double time. The business was geared to term. As soon as term ended, production went down about 40 or 50%.

‘The Chelsea buns were the big thing. Mr Day would only make to the capacity of the ove: 66 buns on a tray, then four loads on a weekday, seven on a Saturday. Mrs Day had a cast-iron control on the shop. Anything slapdash it went straight back.

‘In the second firing we baked all the small stuff: seven or eight trays of Norwegian crisps, Danish pastries, lemon meringue pie three days a week. Then there was a half-hour stop for breakfast at 9.45 or 10am. Then we made all the cakes, different flavours and decorations, on different days of the week. Monday was plain cakes, Tuesday chocolate cakes and chocolate roll, Wednesday tennis cakes, Thursday ginger roll, and so it went on.’

Fitzbillies continued under the successful ownership of the Days until 1980, when Mr and Mrs Day decided to retire. They sold the business to Clive and Julia Pledger, then newly engaged. The new owners approached Fitzbillies with true 1980s spirit, starting to make chocolates in 1983 and developing a mail-order business.

In 1984 they opened an in-store shop at Eaden Lilley, the department store that then took up most of Market Street, and another Fitzbillies branch in Regent Street. The Cambridge Evening News reported that they had plans to make the business a national chain, but reassured its readers: ‘One thing that will not change if expansion takes place is the company’s distinctive name.’ But in the mid-80s, Fitzbillies’ fortunes started to turn – there was now much more competition with cheaper mass-produced cakes available from supermarkets and an increasing number of fast-food options for students. By 1988, the Regent Street premises were put up for sale, as the owners decided to consolidate the business in the original Trumpington Street premises, and then in April 1991 Fitzbillies went into receivership for the first time.

There was considerable competition to buy the business out of receivership and it went to Penny Thompson, who had been a customer of the business for 20 years and fell in love with it while working there.

She got the business back on its feet and opened the first tea room at Trumpington Street on the first floor, above the shop. In 1998 she launched a website, selling Chelsea buns to customers all over the world. On the first day there were two orders: one from Australia, one from America.

The fire

Undoubtedly the worst moment in Fitzbillies’ 100-year history occurred on the night of 21 December 1998 when a painter and decorator who had previously worked at Fitzbillies went on a burglary spree through Cambridge, starting at Fitzbillies, moving on to student accommodation in Trumpington Street and then breaking into a newsagent before being caught fleeing the scene by police. He had a bunch of 20 keys, including those for Fitzbillies. It was alleged that during the burglary, perhaps frustrated by not managing to break into the safe, he set fire to a roll of brown paper. He was, however, never convicted of arson.

Whichever way the fire started, Fitzbillies was almost destroyed. The entire building was gutted and the ones on each side completely blackened with smoke. The Cambridge Evening News reported that, ‘at the height of the blaze, 35 firefighters from Cambridge, Cottenham, Sawston, Papworth and Swaffham Bulbeck battled thick smoke to fight the flames in the three-storey building in Trumpington Street. Efforts to tackle the fire were hampered by difficult access to pitched roofs at the rear of the building, which prevented crews from using ladders in the normal way, and by the collapse of the roof and internal floors.’

As soon as the buildings were declared safe, Old Tom went in to see what could be salvaged. The photos he took show a scene of total devastation. It must be one of the worst things any business owner can face.

Rebuilding Fitzbillies

Penny fought to keep the business alive. By October 1999, while work continued to rebuild 52 Trumpington Street, Fitzbillies opened a temporary shop next door at number 51 and started selling Chelsea buns again. The buns were baked by the Fitzbillies bakers, who were given workspace at Balzano’s bakery in Cherry Hinton Road, a wonderful example of local businesses supporting each other in times of need. Everyone who loves Fitzbillies will always owe a debt of gratitude to Balzano’s. Without them, it is doubtful the business could have kept going.

It took nearly two years to rebuild Fitzbillies, pretty much from the ground up. Pembroke College, the landlord, did a fine job building a new modern bakery at the back and restoring and recreating in painstaking detail the original design of the Art Nouveau shopfront. Eventually Fitzbillies reopened the cake shop at 52 Trumpington Street and next door, number 51, became the café/tea room.

Fitzbillies continued through the first decade of the new millennium, selling old favourites and adding new cakes to the range, but it faced more and tougher competition. In February 2011 the bailiffs knocked again…

‘BARONESS FITZBILLIES’

Perhaps the greatest honour ever not quite paid to Fitzbillies was by the redoubtable Jean Barker, later Baroness Trumpington, a true Cambridge character from her days at Bletchley Park.

A former colleague of Baroness Trumpington wrote to The Times shortly after her death: ‘There was another title that the then Jean Barker was contemplating when made a baroness. Shortly after her peerage was announced, I asked her what title she would take. She said: “I wanted to be Lady Fitzbillies, but they won’t let me!”’