There’ll be blue birds over the White Cliffs of Dover

Tomorrow, just you wait and see.

There’ll be love and laughter and peace ever after

Tomorrow, when the world is free…

—NAT BURTON, “THE WHITE CLIFFS OF DOVER”

THE WHITE CLIFFS OF DOVER

Crossing the English Channel from eastern France or Belgium to southeastern England, the first thing you see on the horizon is the legendary White Cliffs (figure 19.1). They have symbolized the notion of England as an island-fortress, and psychologically they serve as castle walls or ramparts against invaders from the continent. However imposing they may seem, invaders have always found a way around them. The armies of William the Conqueror found a low spot at Pevensey between the White Cliffs to land their boats, and then moved inland to conquer England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Nevertheless, the White Cliffs were a welcome sight to British troops fleeing the beaches of Dunkirk in 1940, or to Allied bomber crews trying to nurse their crippled aircraft home. During the Battle of Britain, they served as a strategic high point for observers reporting waves of German aircraft on the way, and also for the location of the secret radar towers that allowed the British to know of the incoming aircraft well in advance. The White Cliffs were also a sentimental symbol of England, as typified by the old World War II ballad, “The White Cliffs of Dover,” which nostalgically transported homesick British troops back from the battlefield in Europe to a peaceful life in England. In 2005 a poll of listeners in Radio Times voted them the third greatest natural wonder in Britain. One of the old Roman names for England, Albion, comes from the Latin word “white” and probably refers to the chalk cliffs that the Roman invaders had to skirt.

Figure 19.1

The White Cliffs of Dover: (A) Viewed from the Dover Strait; (B) the overlook at its highest point, Beachy Head. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

WHAT IS CHALK?

The White Cliffs get their color from their bedrock, which is known as chalk. When most people hear the word “chalk,” they think of the sticks of white powdery material used to write on blackboards for generations. Even though real chalk was once used for that purpose, most modern blackboard “chalk” is not made of chalk at all, but powdered gypsum compressed into sticks.

Real chalk is soft, white, porous limestone composed of the mineral calcite (calcium carbonate, or CaCO3). It forms under deep-marine conditions from the gradual accumulation of minute calcite shells (coccoliths) shed from micro-algae known as coccolithophores (figure 19.2). Flint (a type of chert typical of chalk) is very common as bands parallel to the bedding or as nodules embedded in chalk (figure 19.3). It was probably derived from sponge spicules or other siliceous organisms as water was expelled upward during compaction. Flint is often deposited around larger fossils that may be silicified (i.e., calcite replaced molecule by molecule by silica).

Figure 19.2

Chalk is made of tiny calcareous algae known as coccolithophorids that secrete coccoliths, button-shaped plates that surround them and measure only a few microns across. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 19.3

Black flint layers are common in the Chalk. (Photo by the author)

The Chalk is rich in fossils that can be collected on the beaches in many places. It is famous for its heart urchins and sea urchins, intensively studied and written about by paleontologists, and yields a variety of clams and oysters, especially the weirdly coiled oysters Gryphaea and Exogyra, which also have been widely studied by paleontologists. The formation also yields a few poorly preserved ammonites, as well as shark teeth and various fish fossils.

Chalk has greater resistance to weathering and slumping than the clays with which it is usually associated, thus forming tall steep cliffs where chalk ridges meet the sea. Chalk hills, known as “chalk downland,” usually form where bands of chalk reach the surface at an angle, so it forms a scarp slope. Because chalk is well fractured, it can hold a large volume of groundwater, providing a natural reservoir that releases water slowly through dry seasons.

The chalk outcrops are not restricted to southeastern England. The belt of chalk actually extends to the Alabaster Coast of Normandy and Cape Blanc Nez across the Dover Strait. There are chalk beds beneath the Champagne region of France that produces the soils for planting Champagne grapes and natural caverns for wine storage. The Chalk extends farther east through Belgium and countries to the northeast, including Jasmund National Park in Germany and Mons Klint in Denmark. The Chalk was such a distinctive and widespread unit across so much of Europe that in 1822, Jean-Baptiste-Julien D’Omalius D’Halloy named the Cretaceous Period after it, from the Latin word creta, which means “chalk.”

THE SHALLOW SEAS OF THE CRETACEOUS GREENHOUSE WORLD

Ninety million years ago what is now the chalk downland of northern Europe was calcareous ooze accumulating at the bottom of a great sea. Chalk was one of the earliest rocks made up of submicroscopic particles to be studied under the electron microscope, when it was found to be composed almost entirely of coccoliths. Their shells were made of calcite extracted from the rich seawater. As they died, a substantial layer gradually built up over millions of years and, through the weight of overlying sediments, eventually became consolidated into rock. Later movements of the earth’s crust related to the formation of the Alps raised these former seafloor deposits above sea level.

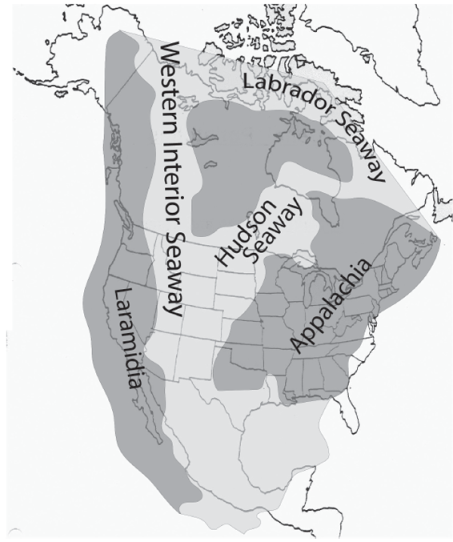

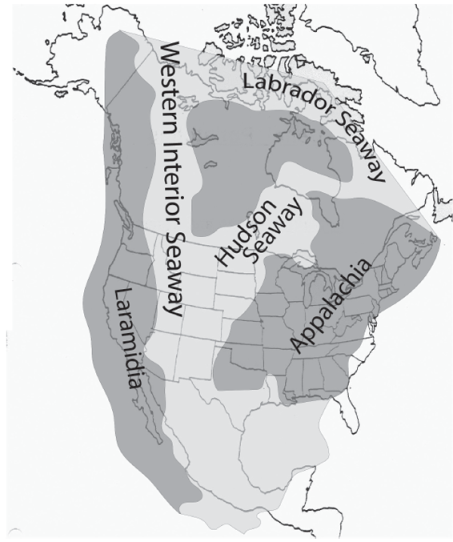

The Chalk is also a product of a much bigger phenomenon: the global greenhouse world of the Late Cretaceous. During the latter half of the Age of Dinosaurs, the climate was so warm that dinosaurs roamed above the Arctic and Antarctic circles. There was virtually no ice and snow anywhere at that time, since the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were about 2,000 parts per million (today the level is over 400 parts per million and climbing). The melting of all those icecaps resulted in extremely high sea levels, and shallow seas drowned many of the continents. The shallow chalk-rich seas of the Cretaceous drowned most of Europe, as the distribution of the Chalk not only in England but in Belgium and France attests. The rising sea level flooded the Central Plains of North America, producing the “Western Interior Cretaceous Seaway,” which connected the Arctic Ocean with the Gulf of Mexico (figure 19.4). Those seas were filled with ammonites, clams, snails, and huge fish and marine reptiles, which are found today in chalk beds such as the Niobrara Chalk in western Kansas (figure 19.5) or the Austin Chalk of central Texas.

Figure 19.4

The Western Interior Cretaceous Seaway flooded the central plains of North America, from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. (Redrawn from several sources)

Figure 19.5

Monument Rocks, Gove County, Kansas. Chalk is found not only in Europe, but in the Cretaceous beds of central Texas and western Kansas. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

None of these things were known, however, when the legendary English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley gave his lecture “On a Piece of Chalk” to the working men of Norwich at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1868. A firm believer in educating the masses about science and nature, Huxley chose to use a piece of humble chalk on his chalkboard as the subject to spin an engrossing tale of all the geologic events that occurred to make that chalk, what kinds of fossils it was composed of, and what these ancient chalk seas must have once looked like. The lecture was subsequently published as a book, and it still stands today as one of the great works of science popularization—and one of the first ever published (and it is now available free online). Nobel Prize–winning physicist Steven Weinberg calls it “one of the best books ever written for the general science reader.” Reviewer Dael Wolfle of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science wrote in 1967:

That the lessons of paleontology are now so much more widely appreciated than they were when Huxley drew them from a piece of carpenter’s chalk is in good measure a tribute to Huxley’s genius. We have much more factual knowledge than he had, but we have no better exemplar of the art of explaining in compelling and understandable terms what science is about, nor a more vigorous example of the scientist’s obligation to practice that art.

FOR FURTHER READING

Everhart, Michael J. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Huxley, Thomas Henry. On a Piece of Chalk. New York: Scribner’s, 1967.

Skelton, Peter W., Robert A. Spicer, Simon P. Kelley, and Iain Gilmour. The Cretaceous World. Edited by Peter W. Skelton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Smith, Andrew B., and David J. Batten, eds. The Palaeontological Association Field Guide to Fossils, Fossils of the Chalk. 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002.